The creator of Apple’s most popular show, Ted Lasso, has struck a deal with the streamer to produce a new comedy for them!

Genre: TV 1 Hour Comedy

Premise: A suspended Florida Keys cop must solve the strange case of a man’s arm that was found floating in the ocean.

About: Bill Lawrence is going to try and do the same thing for Vince Vaughn that he did for Jason Sudekis, giving him an Apple show perfectly suited for his talents. Lawrence has had an incredibly successful career. He wrote his first TV episode back in 1993 on Boy Meets World. He later developed Spin City, Scrubs, Cougar Town, and most recently, Ted Lasso. This guy must have a house the size of a large island. Michelle Monaghan (Mission Impossible franchise) will also star.

Writer: Bill Lawrence (based on the novel by Carl Hiassen)

Details: 61 pages

I’m far from an expert on cop shows. I just know that it’s the most well-tread TV genre of them all. And that’s something writers have to beware of. Whenever you’re entering well-tread territory, you have to work harder to come up with a fresh angle. Cause you have a lot more competition.

For example, if you write a zombie script, you have to realize that you’re going up against soooooooo many zombie scripts. So if yours is another basic zombie outbreak story, it’s not going to stand out. Just like if you write a cop show, you probably don’t want to set it in New York City.

And that’s actually a great way to separate your cop show from others – find a unique location. A cop show in Alaska is going to be a lot more unique than a cop show in Los Angeles.

Here, we’ve got a cop show set in the downtrodden “backwoods” sector of waterfront Florida – the West Keys – a sort of “Anti-Miami Vice.” That alone is going to separate it. Also, since there are a lot more dramatic cop shows out there than there are comedic ones, you have a secondary factor separating your show.

Which is why Bad Monkey feels like its own thing.

The story follows a suspended cop in Key West Florida named Andrew Yancy. Yancy is either doing one of two things – being a cop or chasing women. And since he’s suspended, he’s happy to use that extra time chasing women.

But then Yancy’s partner comes to him with a severed arm (whose hand still has its middle finger extended) that was found by a fisherman in the ocean. He wants Yancy to get rid of it. Opening up a case for a dead body based on a severed arm would disturb the community and also create a lot of headaches for an incident that clearly happened in Miami (and therefore has nothing to do with them).

But Yancy’s cop training won’t allow him to throw it away. He asks a hot coroner to take a look at it. She’s got nothing for him. His partner eventually gives Yancy good news. A woman claims the arm belongs to her husband who died during a terrible boating accident. “Just give her the arm and walk away,” his partner says.

But Yancy can’t help himself. He starts asking the woman questions. Notices her pull an Amber Heard (try really hard to cry). Now he’s suspicious. So he goes to the funeral and meets the man’s daughter, who swears that the wife killed him. Which means Yancy’s got a bone. And he’s going to hold onto that bone all the way until he solves this case and gets his badge back.

I used to hate that cop movie trope where the officer would lose their badge at the midpoint because they did something illegal but still decide to pursue the case anyway. It was so cliche it actually hurt to watch.

But now I understand why writers do it. It creates a much more interesting character situation. For starters, the character is now acting illegally. So if he gets caught, he’s in a lot more trouble, which of course creates more tension and suspense.

He’s also neutered, like a superhero without his powers, which forces him to be more creative (always force your heroes to be more creative!).

Finally, it allows you to cheat as a writer. There are a lot of rules cops must abide by. But those rules don’t apply if you’re not officially a cop. You wouldn’t go into a dangerous situation without backup for example. But if you’re not officially a cop, you don’t need backup.

I noticed all this while reading Yancy’s story.

I also noticed that Bill Lawrence doesn’t give a crap about impressing readers. His writing style is almost anti-reader. I suppose if every TV project I wrote went to air and became a hit, I wouldn’t worry about readers either. But to give you an idea of what I’m talking about, the first paragraph of the script is 12 lines long!

Here I tell amateur writers they can’t get away with this yet now we have verifiable proof of a professional screenwriting doing so. Like I mentioned, guys, when you have five hits under your belt, Hollywood will let you write your scripts on toilet paper in the comic sans font. Heck, they’ll let you write them in Celtx.

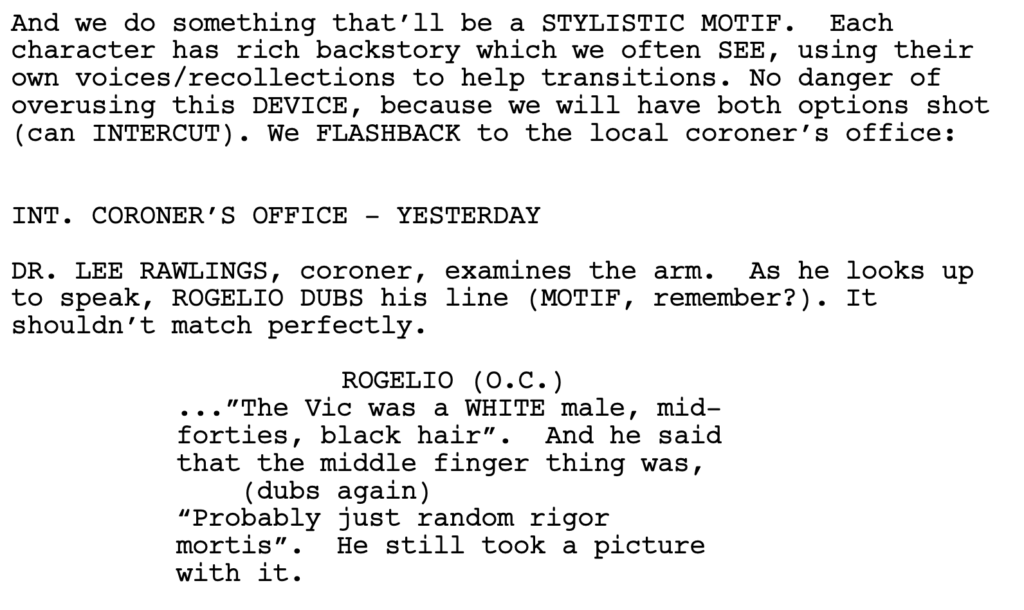

There’s also some very advanced technical stuff going on here. For example, here’s Lawrence writing a highly complicated voice over scenario…

I warn writers away from this kind of stuff only because anything that’s hard to explain might confuse the reader. Too often as writers we think the reader can read our mind. I’ll often tell the writer, save the complex version for when your pilot is purchased and you’re going into production. When it’s still a spec, keep things easy to read. Coming up with some complex voice-over scenario – like something you’d see on Euphoria – it’s too big of a gamble when you’re an unknown dealing with impatient low-level readers.

It’s worth discussing why Bill Lawrence is so successful. Because we’ve seen plenty of writers who write a good show then never write a good show again. What is it that Lawrence is doing differently?

My friends, when it comes to TV, it’s all about the main character. If your main character is the right combination of likable and interesting, we’re going to be on board. Yancy could’ve been written as a deadbeat cop who didn’t give a sh#@ about anyone but himself. Instead, Lawrence kept the lazy morally-questionable womanizing aspect of the character, but balanced it out with a guy who loves doing his job.

It’s such an advantage when your character is active, like Yancy. Because active characters push stories forward. I was talking about this with a writer not long ago. He was wondering if he should write a “Lebowski” type character who didn’t care about anything but chilling and getting high. I told him, if he does that, the character is going to be too passive and hard to root for. The genius about The Dude was that while he preferred to be lazy, the circumstances required he be active.

If Lebowski just sat around all day, we wouldn’t like him at all.

Which is a long of way of saying, find any possible way to make your hero active, even if they don’t want to be. Cause that always creates a better narrative. And here, Yancy can’t help but to investigate this severed arm. Cause he’s a cop at heart.

And by the way, this is why there are more cop shows than any other genre on television. Cops have THE MOST ACTIVE JOB there is. They always have some place to be, some crime to solve, some issue to settle. And as soon as they solve it, they’re handed another one.

Just make sure that if you write a cop show, you check with some people that it’s a unique idea.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Location is a great way to spice up cop show concepts. A cop on the moon. A cop on a tropical island. A cop stationed at the biggest airport in the world. Just like the real estate industry, it’s all about location, location, location!

Are screenwriters even trying anymore?

Genre: Sci-Fi/Action

Premise: An evil corporation charged with protecting dinosaurs uses their research to create a worldwide food collapse and it’s up to some old Jurassic Park friends to stop it!

About: The final film in the Jurassic World trilogy pulled in 143 million dollars. For some reference, Jurassic World, the first film in the new trilogy, made 208 million dollars. The original Jurassic Park made 95 million in its opening weekend when adjusted for inflation. The newest film in the franchise was promoted mainly by the return of legacy characters.

Writers: Story by Derek Connolly and Colin Trevorrow. Screenplay by Colin Trevorrow and Emily Carmichael

Details: 2 hours and 30 minutes

You may be asking yourself, why are you even reviewing this, Carson?

In the landscape of cinema, it’s about as unimportant a big-budget Hollywood release as there is.

There are two reasons.

One, Jurassic Park remains the single best movie concept ever. A theme park with real dinosaurs. There isn’t an idea out there that beats it. So I think that’s worth covering as a screenwriting critic. As much as you want to dig into the weeds on how to write a good screenplay, it all comes down to the idea. If people like your idea, they want to read your script. If they don’t, they don’t.

The second reason is that I’m fascinated by Colin Trevorrow’s career.

He broke through with a decidedly average indie movie, Safety Not Guaranteed. Based on that movie, he got the Jurassic World job. Jurassic World massively over-performed, which led to him getting the Star Wars Episode 9 job. He then made The Book of Henry, which had one of the most ridiculous plots ever known to man. The badly received film got him fired from Episode 9, which left him with nowhere to go. So he came back to Jurassic World for this movie.

But after this film, he no longer has the franchise for cover. He’s out there naked to the world and, therefore, if things don’t go right, he could become the next Joel Schumacher or John McTiernan. So you want to finish the franchise off with a good movie. Because good movies are memorable and you can use that to book jobs.

I know Trevorrow is already set to make an Atlantis movie, which I think is a smart move for him. But if this film’s box office takes a massive dive in its second week because word-of-mouth is so bad, there’s no guarantee that that Atlantis film will be made.

I have no idea what’s going on here.

I have no idea what’s going on here.

So what’s this latest film about?

Oh boy.

I’m going to keep this as short as possible. A company called Biosyn has created a sanctuary for dinosaurs. Also, a new type of Dino-locust (aka a really big locust) is eating up all the crops across the planet. Conveniently, Biosyn has a pesticide that prevents the locusts from eating crops. Buy Biosyn and your crop problems are solved.

Out in the middle of nowhere, Owen (Chris Pratt) and Claire (Ron Howard’s daughter) are raising Maisie, a clone of her mother, who died. The same bad guys who kidnapped Baby Leia also kidnap Maisie. This means Owen and Claire have to find her.

Meanwhile, legacy characters and scientists, Ellie and Allen, are recruited by Biosyn to try and figure out why these locusts are killing all the crops. So they come to Biosyn Headquarters where they meet up with Jeff Goldblum, who I guess is teaching classes there. They eventually also meet up with Owen and Claire, who have tracked Maisie back to Biosyn. The group then escapes, forcing them to take on all the dinosaurs in the sanctuary.

I’ve been noticing a lot of reviews of this movie focusing on the bad writing.

Those reviews are correct.

However, as always is the case with screenwriting, there’s a nuanced discussion to be had. I just think the task here was so big that it overwhelmed the writers, which is why the story is so clunky.

First off, you’ve been told you have to bring in the legacy characters in a significant role. Which means you have to create a parallel storyline for them. And this is where things get messy.

While it’s true that parallel storylines are part and parcel in today’s mega-blockbusters – The Avengers have so many characters, they have no choice but to split them up – the tough part about Dominion is that our current characters in the series aren’t connected to the legacy characters. So it can’t be a collaborative storyline that splits them apart. It has to be separate.

And this is where the bulk of the movie’s problems originate. Alan and Ellie (our original Jurassic Parkers) are wrapped up in an oddly complicated locust storyline whereby if they don’t figure out how to stop the spread of the larger Jurassic locusts, the locusts will single-handedly destroy the planet’s food chain.

Meanwhile, Owen and Claire are involved in a traditional Taken-style storyline where they have to retrieve their adopted daughter. This was actually a smart move by the writers, who must’ve realized how laborious the locust storyline was and figured they had to offset it with the simplest storyline possible.

Ironically, either the director or the producers or someone else wasn’t satisfied by that simplicity, and therefore decided to make the daughter’s storyline evolve into something even MORE complicated than the locust storyline. Without getting into detail, the adopted daughter is a clone who has overcome a deadly genetic disease and, therefore, Biosyn must use her to figure out how to stop the locusts.

You’d think that, at some point, someone would’ve said, “This is just way too complicated.” But once these big movies get moving, they’re like a tidal wave. They’re not going to stop until they hit shore. And whatever they’ve accumulated along the way is coming with.

The crazy thing is, if you break it all down – every single plot development in this movie – it *does* make sense. But therein lies the problem. Audiences don’t come to movies to make sure they make sense. They come to be entertained. So that should always be your primary directive. Sure, you don’t want plot holes. But plot holes are not above entertainment on the movie priority list.

What’s so frustrating is that you could see the writers *trying* to do the right thing. You have the cloned girl, Maisie. The writers went really deep into her backstory and her flaws and her conflicts to create an emotionally complex character. That’s what we’re told to do, right? Create complex characters. So this is right, right?

Or you have Dr. Henry Wu. Dr. Wu is responsible for creating these locusts that will destroy the food supply in order to help Biosyn sell the solution to everyone. He then has a change of heart, realizes what he did was wrong, and attempts to right that wrong by kidnapping Maisie to study her genetic abnormalities in order change the genetic code of the locusts so that they’ll all die off.

Look at how complex this character is. He did something terrible. Now he’s trying to make it right. So he does something terrible again, in an attempt to make it right. Isn’t this exactly what we tell screenwriters to do? Make these complex characters who have all of these conflicts inside of them? They’re both good and bad. That’s proper character construction, right?

In addition to this, we have a brand new character, a sort of Indiana Jones type, named Kayla Watts, played by DeAndra Wise. She’s a pilot with an attitude. Kayla also becomes part of the complex character brigade. She’s been a thug-for-hire her entire career, always chasing the buck over doing the right thing. She stands by as Maisie is kidnapped, has a crisis of conscience about allowing the Jurassic Park version of child trafficking, and decides to help the good guys to right her moral wrong.

Again, on paper, we’ve got a complex character here. I can imagine the writer’s room discussions over this character. How interesting she is for having zero morals her whole life then finally deciding to do the right thing instead of collect a paycheck. I’m sure there were a few people in the room crying about how powerful her arc would be.

So how come not a single audience member cared about these three characters?

There’s an acronym that’s popular in the sports world called “KYP.” It stands for Know Your Personnel. And never has this acronym been more relevant than in regards to this movie. The reason you’ve got three extremely complex characters that nobody is responding to is because they’re the wrong characters. People aren’t coming to this movie to hang out with these three randos.

They’re coming to hang out with Owen, with Clair, with Ellie, with Alan, with freaking Jeff Goldblum. That’s your movie right there. And the fact that you spent all this time building up characters that never stood a chance no matter how well they were written, shows an inability to recognize what people care about.

This is exactly why Top Gun has taken over the world. It recognized that people wanted to see Tom Cruise.

Granted, Chris Pratt’s “Owen” is no Tom Cruise. With that said, there was ZERO attempt to do anything with his character. THE LEAD CHARACTER IN THE FILM! He’s got like 10 lines the whole movie. Yet Boring Indiana Jones Ripoff Girl gets 90% of the dramatic beats in the movie. It was a bizarre decision to say the least.

Speaking of, there was a lot of blowback in the last two movies regarding Owen and Claire bickering with each other. A lot of people called it misogynistic or something. Well, those critics and Twitter users bullied the filmmakers into getting rid of that dynamic. And, in the process, they made Owen and Claire’s interactions the single most boring interactions between two leads you’ve seen in a movie all year.

So the next time you’re thinking of changing something because of people complaining on Twitter, consider what that actually does to the entertainment value of your movie. You’d already neutered Owen as a character. To then neuter his relationship as well… it made these two characters invisible.

I’m not pretending that any of the solutions here are easy. As a screenwriter on a major blockbuster, you’re juggling 10,000 plates. But someone on this team should be reading Scriptshadow. Because I remind people all the time of the best screenwriting advice on the market: KEEP IT SIMPLE STUPID.

The more complex you make your screenplay, the worse it’s going to be.

This film is the latest example of that.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’ve ever been confused by the note, “Too much plot,” watch this movie. This movie is the poster child for “too much plot.” Generally speaking, if almost every scene in your script has your characters explaining something, it means that your plot is too overbearing.

What I learned 2: Be aware of “negative space.” Sometimes as writers we will eliminate a problem in our screenplay but not replace it with a solution. Therefore, what’s left in its place is “negative space.” That’s what happened here with the “bickering couple” criticism that had Trevorrow erase all bickering between Owen and Claire. True, he got rid of the problem. But he didn’t replace it with a solution. He just left negative space. This is the same thing that happened with Jyn Erson in Rogue One. They quickly realized that Jyn came off as “bitchy.” So they erased all moments where Jyn was bitchy. They got rid of the problem. But they didn’t come up with a solution. This is why Jyn Erso is one of the most forgettable Star Wars characters ever. You can’t just erase the problem. You gotta replace it with a solution.

The longer I do this, the more convinced I become that the “in the moment” story is more important than the overall story. What do I mean by that? As long as the story going on in the current scene is entertaining, you’re going to keep the reader hooked. Because if I’m entertained by the first scene and then I’m entertained by the second scene and then I’m entertained by the third scene, and so on and so forth, I’m going to want to keep turning the pages until the script is done.

However, if the individual scenes are hit or miss (I’m entertained by the first scene, I’m bored by the second scene, I’m kinda entertained by the third scene, I’m bored again by the fourth scene) it won’t matter how good the overall story is. Because the pieces within that story are struggling to keep my attention. And as anyone who’s read scripts knows, we don’t finish reading scripts like that.

This begs the question, how do you make each and every scene entertaining? Who out there has the ability to write a good scene EVERY TIME OUT? Isn’t that an impossible standard to live up to? If you’re going by the odds, some of your scenes have to be bad. Right?

Wrong.

This is a toxic way to think.

While it’s true that not every scene can be great – even scenes from some of our favorite movies suck – there’s a method you can use to ensure that your scenes will rarely, if ever, be bad. And by using this method, your likelihood of writing a good scene goes up exponentially.

The method I’m talking about is built around the idea of CONFLICT.

Now we’ve been told ad infinitum that our scenes need conflict. The problem with this advice is that that word is vague and unhelpful when you’re constructing a scene out of thin air. So I’m going to help you see conflict in a new way. And this way should help your scene-writing dramatically.

From now on, I want you to look at every scene as requiring a POSITIVE CHARGE and a NEGATIVE CHARGE. If you live by this simple rule, every scene you write is going to have conflict. Conflict, of course, naturally results in drama. And drama is the magical component that ENTERTAINS audiences.

Let’s look at the simplest version of this – positive character, negative character.

If you watch a movie like Fury Road, you have lots of scenes with your positive charge character, Furiosa – she’s trying to save a group of people – going up against your negative charge character, Mad Max – who’s trying to escape. Every scene between these two characters is entertaining because those opposing charges are always on display.

This is a great way to ensure that most of your scenes will be entertaining. You simply take the two characters who are going to be around each other the most in your movie and you assign one of them a permanent positive charge and the other a permanent negative charge. This guarantees that every scene these two are in is going to have some level of conflict, which is why the scene will probably be good.

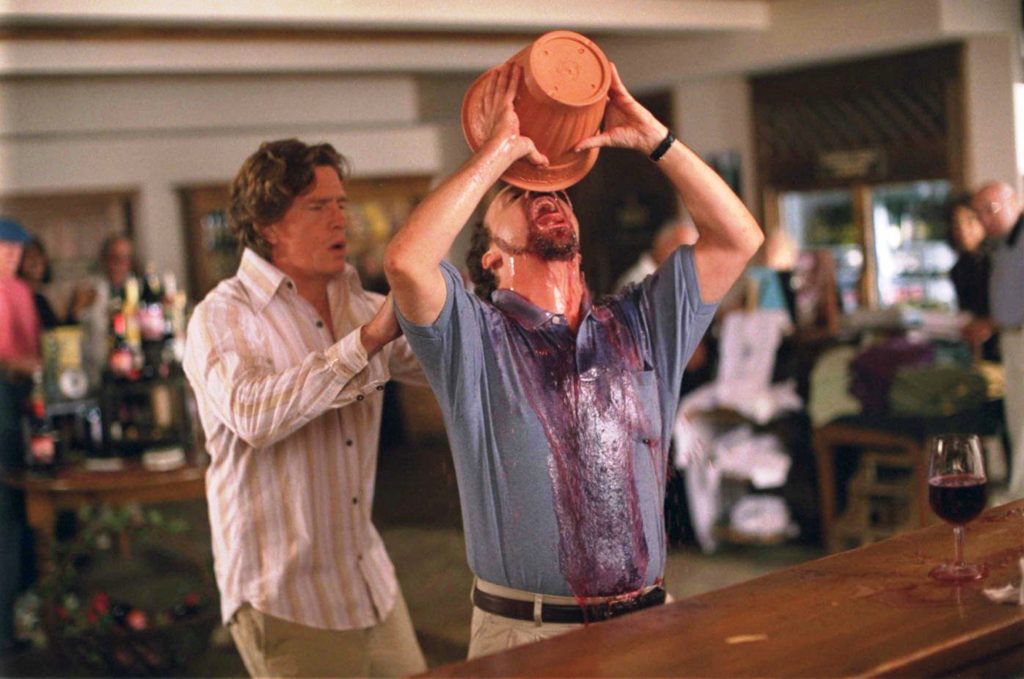

This can work especially well if your narrative is purposefully flat. A great example of this would be the movie Sideways, which follows two friends up to Napa Valley for the weekend. It’s not a plot movie by any means. But the two friends were Jack (positive charge) and Miles (negative charge). Their essence as humans was so embedded in that positive or negative belief system that they didn’t need plot to be entertaining. They just needed to be around each other.

Unfortunately, not all of us are interested in writing buddy cop movies or road trip movies. Which puts you in a more difficult position. Because now instead of the positive and negative charges automatically being there for you in every scene, each scene requires you to find a new positive and negative charge.

This is where screenwriting gets tough. Because each scene becomes a unique challenge to find the charges. And if you’re lazy, you won’t bother doing so. But luckily you have me and I can give you some direction. The second type of positive-negative charge is TEMPORARY CHARGES.

In this scenario, your characters may or may not be carrying permanent positive or negative charges, which means the scene itself must be constructed in a way to give each character in the scene a positive and negative charge.

The most obvious example of this is Character A is mad at Character B about something and lets them have it. Character A is our negative charge (he’s mad!). Character B is our positive charge (he’s trying to defend himself and calm A down). To be clear, Character A may be a positive person throughout the rest of the script, but right now he’s mad, so he becomes the negative charge for the scene. That’s the thing with temporary charges. You can construct them for the moment. They don’t need to be attached to the character’s permanent identity if the scenario calls for it.

But anger isn’t the only negative charge in your Charge Arsenal. I recently watched a movie called Red Rocket. A great film. It’s going to be one of my favorite films of the year. It’s about a former porn star, Mikey, who moves back to his Texas hometown with no money. One of the early scenes has him going to Leondria, a drug dealer, to see if he can sell weed for her.

This is a very simple example of a temporary positive charge temporary negative charge scene. Mikey is the positive charge. He’s trying to get something to better his life – make money so he can move back to Los Angeles. And Leondria is the negative charge. She’s suspicious of Mikey. She’s also potentially dangerous. She doesn’t really want him selling for her. That’s what makes the scene entertaining, is the positive charge being forced to interact with the negative charge.

And by the way, if you want to see a masterclass in positive-negative charges, go watch Fargo (the film). The reason almost every scene in that movie is a classic is because that’s all the Coens focused on back then, was positive and negative charges.

Okay, let’s get a little more nuanced now. Let’s say that you have two characters who get along. Which means, in the majority of their scenes together, they’re both going to be positive charges. This will usually happen when two characters fall in love. So now what? How do we create conflict if two people are on the same page?

Simple. We introduce a negative charge EXTERNALLY. Romeo and Juliet is the perfect example of this. Romeo and Juliet are both positive charges. But their families are both negative charges. Which means you just have to bring a family member (negative charge) into a scene to create conflict. Or, in some cases, just the threat of Romeo and Juliet being caught out with each other can be a negative charge. Think about it. These two aren’t hanging out without a care in the world. They’re hanging out always having to look over their shoulders. Why? Because behind their shoulders is that looming negative charge.

This is what James Cameron did with Titanic as well. At first, Jack and Rose were opposing charges. He was positive (trying to get her) and she was negative (she was resisting). But once they got together, they both became positive. And that meant Cameron had to create a series of external negative charges to keep their scenes entertaining. He did this with Cal Hockley, Rose’s fiancé. He did this with Hockley’s undertaker assistant, who chased them around. And he eventually did it with the ship itself – the sinking and all the problems it created were the primary negative charge in many of their scenes.

Now here’s a question for you. What if you only have one character in a scene and he’s not in a scenario where he’s opposite a negative charge? How do you create the necessary conflict to ensure an entertaining experience for the viewer? This is where writing gets fun. You create the charge FROM WITHIN. One charge will be the external and the other charge will be the internal.

So let’s take a look at Arthur Fleck, the Joker. The reason that Arthur looking in a mirror can be a compelling scene all on its own is because externally he’s struggling to be happy (negative charge). Yet internally, he’s desperate to be happy (positive charge). Which is why he’s shoving his fingers into the sides of his mouth and forcing them up. He wants to smile but he can’t.

If the Joker were to smile and there was no resistance at all, there’d be no conflict. So the scene wouldn’t be dramatic. Hence, the importance of opposing charges.

All of this boils down to when you’re in a scene, ask yourself, where is the positive charge coming from and where is the negative charge coming from? If you have that in place, there’s a good chance you’ll write an entertaining scene. The reason I say “good chance” and not “guaranteed” is because screenwriting is composed of too many variables that affect each scene.

Take a look at the Obi-Wan Kenobi show. Many of the scenes in the second episode followed the rules I laid out above. They have Obi-Wan in them, our positive charge (he’s rescuing Baby Leia), and Baby Leia, who represents our negative charge (she resists his help and is not thankful). These scenes should work according to me. Both characters have an inherent opposing charge. Why, then, do the scenes suck? They suck because Baby Leia is a poorly written character. We don’t like her. We don’t want to be around her. Even the most well-constructed version of conflict in a scene will fail if we don’t like (or are interested in, or care about) one of the characters in the scene.

So obviously, other parts of your screenplay need to be on point. But at least now you know that if you inject that positive and negative charge into every scene, there’s a good chance you’ll write a dramatic scene. And since drama equates to entertainment, we’re going to be invested in each and every one of your scenes. Go forth and try this in your current script and watch how much better your scenes get.

Genre: Action/Comedy

Premise: The adoptive daughter of a legendary assassin returns home for his funeral… and finds herself in the crosshairs of her four highly trained, highly dangerous siblings.

About: This script has one of the flashier loglines on the Black List. The writer, Ryan Hooper, is just starting his career. The project is set up at Thunder Road, the production company responsible for John Wick, which implies this could be another project they’re looking to integrate into the John Wick universe.

Writer: Ryan Hooper

Details: 104 pages

Based on the main character’s name, I’m guessing it was written for Kravitz.

Based on the main character’s name, I’m guessing it was written for Kravitz.

First off, good title.

Titles are always tricky and one way to stand out is to do a riff on a previous well-known title. Four Weddings and a Funeral is a well-known movie with one of the better titles in history. Take note that when you are riffing on other titles, it tends to work best when your movie is a comedy.

As for the concept itself, I think it’s pretty sexy. It’s a mix between Knives Out and Ready or Not. I could see a lot of executives flipping for that kind of pitch in the room.

But there is something about the idea that worries me. I’ll share that after the plot summary and let you know if the writer was able to overcome this issue.

Joel Ferrier is a legendary assassin who is part of a board of assassins who perform high level hit jobs around the globe. So it should be no surprise that he trains his four children to be hit men as well. There’s the oldest, image-is-everything Todd, then feisty Violet, then loving Dominic, then snazzy Portia.

And finally, there’s the mixed race youngest of the clan, Zoe. Zoe is adopted and, therefore, not treated equally by her brothers and sisters. In fact, they barely pay attention to her at all. So when they grow up and get a call that their dad died in Vegas of a heart attack, they’re actually kind of surprised to see Zoe show up for the funeral.

But what really surprises them is when the lawyer reads the will. All the money goes to Zoe’s mother. And since Zoe’s mother is dead, all the money goes to Zoe. Violet becomes enraged and decides right then and there, she’s going to kill Zoe. She lets the others know you’re either with me or against me. They decide they’re with her.

Zoe runs for her life and starts hiding around her family’s giant estate, eventually getting her hands on a jump drive. Zoe becomes convince that there’s more to this story of her father’s death and tries to find her way to a computer where she can look at what’s on that drive before Violet kills her.

She eventually finds out that her father, along with two other board members, were murdered by a stealth group of assassins led by Violet, who disguised the killings as suicides. Which means, of course, that Violet can’t allow Zoe to escape the estate. If she does, the other board members will know what she’s done, and kill her before she can complete her takeover. Can Zoe escape four of the most highly trained assassins in the world? I guess we’ll find out!

Today I want to talk about how some loglines can sound really good as loglines yet be really tricky to turn into screenplays. And Four Assassins is that kind of screenplay.

I love this logline. It’s fun. Kind of like a higher-stakes version of Knives Out.

But think about sitting down to expand this idea. For starters, you have to convincingly come up with a scenario where four siblings want to kill a fifth sibling. Since siblings don’t tend to want to kill each other, most of the motivations you come up with are going to feel forced.

Hooper began solving this issue right away by making Zoe adopted. She was never really a member of the family. But how do we go from that to: the four people you grew up with want to kill you?

It’s a huge leap and one that will determine the amount of buy-in necessary for the audience to suspend disbelief.

What Hooper ended up doing is making Violet the only true sibling who wants to kill Zoe (because Zoe has info about what she did to their father). For this reason, I can buy into Violet’s motivation. Her life is on the line if she doesn’t kill Zoe. But I’m not sure I ever bought into why the rest of the siblings agreed to kill Zoe.

They don’t have anything to protect. So, therefore, the only reason they’re going after Zoe is because the script needs them to, because the logline says that’s what happens. Which is a dangerous game to play as a screenwriter. You want your motivations to be strong for every character involved.

However, if you can get past that, it’s a solid script.

I liked that Zoe had her own goal. Because that made her active. I recently did a consultation that was set up in a similar fashion. The main character was bouncing around, running from the bad guys. But because she never had a goal of her own, she came off as reactive the whole time. The antagonist was the one driving the story. And while it’s not impossible to build narratives around the antagonist driving the narrative, you have to note that whenever you do so, your hero will suffer a bit. Cause ACTIVENESS is often a character’s most defining trait. Therefore stripping your hero of that makes them less defined.

By giving Zoe this mystery to solve: What’s on this jump drive? And, on a deeper level, who was her mom and how was she associated with Joel? It gave her more to do than just run away. She becomes an ACTIVE character.

So if there’s any big takeaway from this script, that would be it. If you’re writing a movie where your hero gets chased, add a storyline where they, themselves, are chasing something. My favorite movie ever, Star Wars, applies this device. Luke and Obi-Wan aren’t just running away from a pursuing Vader. They’re trying to deliver the Death Star plans to the leaders of the Rebellion.

Four Assassins is one of those scripts that you nod your head after and say, “Not bad.” The craft is strong. The concept is fun. You can see the poster. But the story didn’t feel like the writer took enough chances. There was a safety net feel to everything that kept the script from becoming memorable. Scripts need to take at least one giant risk to be memorable. That never happened here. With that said, I think the movie would make for a cool trailer. And if a director elevated it not unlike the way Stahelski and Leitch elevated the John Wick script, who knows?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Be careful about using jokes that could’ve been used 20 years ago. Hell, be careful about using jokes that could’ve been used 3 years ago. Cause dated jokes put you in one of two categories. You’re either a) out of touch. Or b) giving us a dated screenplay. When an assassin with long blond hair attacks Todd late in the script, he screams the line, “F#%k you, Fabio! Get off me.” This is the definition of a joke that could’ve been used 20 years ago. With a little effort, you can come up with a more timely reference.

What I learned 2: Give your characters names that sound like their most dominant quality. You have your main antagonist here, who is the most VIOLENT of the assassin family. So what name does Hopper give her? “VIOLET.” Han Solo does his own thing. He operates independent of everyone else. Which is why his name is Han SOLO.

Is this JJ Abram’s big return to prominence? Or is it a five car pile-up waiting to happen?

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: After losing his older brother in a fatal racing wreck, a just out of high school Speed Racer attempts to pick up where his bro left off.

About: As Mr. Crawford informed me, this 1994 draft was intended to be directed by Julien Temple, with a pre-Amber Heard Johnny Depp starring. It was deemed too expensive to produce. Alfonso Cuaron was attached to direct in 1997 but that didn’t work either. The Wachowskis would develop a different script and shoot that back in 2005. The movie did not do well and Speed Racer was quickly forgotten. But JJ never let go of his love for the property and has decided almost 30 years later to turn it into a TV show for Apple. What’s his vision for that show? I assume it’s something akin to his feature treatment, which we’re going to look at today.

Writer: JJ Abrams

Details: 126 pages

I am so torn by what I’m about to experience.

I love JJ.

I hate anime.

JJ. Anime. Anime. JJ.

Even as a kid, when you have zero storytelling discernment – if it’s flashing colors, you’re happy – even as a KID I watched this show and thought it was nonsensical. You can’t turn something nonsensical into a movie and expect good things. You need a base. You need a story. To this day, Speed Racer will be known as the movie that officially slammed the coffin shut on the Wachowskis being considered serious filmmakers.

Is JJ about to make that same mistake? Or has he cracked the code for making live-action anime actually good?

The year is the 50s. We watch as a young man named Rex Racer is racing in a high-stakes race where the tracks are long and weird and have jumps over mountains and stuff. During a particularly difficult section of the track, Rex crashes and DIES! The entire Racer family, including his younger brother Speed, are devastated.

Cut to 12 years later and Speed is now 18. All he wants to do is race but his family is still so devastated by Rex’s death that they don’t even talk about racing. Speed graduates high school and watches, longingly, as his crush, Trixie, heads to London to enter into helicopter school.

Speed finally gets the courage to ask his father if he can race because racing is in his blood and his father shocks him when he takes him to a remote garage and introduces him to the car he’s been building over the last decade. The Mach 5!!! Speed is so excited that he wants to race this weekend. But you haven’t even practiced, his father says. Speed proves that he can handle professional racing by easily beating the lap record at the local speedway.

Just as he’s about to race, he’s cornered by the mysterious Racer-X, who always wears a tinted visor. Racer-X says to him, “Don’t race,” in a very sinister manner. But Speed doesn’t listen, races, and finishes second to Racer-X, which turns him into an overnight superstar, due in no small part to being the younger brother of the deceased Rex.

The next race is a big one and it’s in England! Which means, guess what? He’s going to see Trixie! Except now that he’s a big popular racer, all the women want him, including the seductive Tatiana, who puts all her cards on the table and says she wants to “get naked” with him ASAP.

During the race, Speed realizes that the big time is a lot bigger than he thought. The race is way tougher. And during it, out of nowhere, a giant tree lands in the middle of the speedway and Speed crashes and his car catches fire. To everyone’s shock, Racer-X slams to a stop and runs over to save Speed (BIG SPOILER). When he lifts his helmet momentarily, it’s revealed that Racer-X is actually…. REX! His brother!

But how can this be!?? Later that night, Rex secretly informs Speed that there are higher powers fixing these races, which is why he tried to warn him off them. If you don’t play by the rules, they make you disappear. Is Speed going to give up? Or is he going to keep racing? Something tells me you can’t keep Speedy in the corner. And that both him and his brother are going to rule the racing world together!

Word on the street is that the development process for this project has been agonizingly slow. And I can see why. There are certain tones that have virtually no wiggle room. When you have, say, a romantic comedy, you can develop something that’s goofy, like The Lost City, or romantic, like Love Actually.

But with this… you need to nail a very specific type of humor along with porting what was meant to be animation into live-action, which is a whole other ball of wax that requires an adjustment so sensitive, it’s like trying to land a 747 on a runway the width of a balance beam.

Look no further than Cowboy Bebop to see how quickly things can go south.

With that said, JJ wins again.

This isn’t a great script. But what JJ is really good at, at least as a screenwriter, is telling a simple story well. Which is the foundation of screenwriting. You’re not trying to tell a complex story well. But a simple story. Which is what this is. It’s a kid whose brother died racing but he still wants to be a racer. And that’s it. He races and the races are all fun because they have a bunch of fun wacky car setups.

However, I understand that saying, “He tells a story well” is a vague statement that helps no one. So let me give you an example of what I mean. At the beginning of the second act, Speed reveals to his father that he dreams of being a race car driver, like his brother. So his father gives him his first racing car. Speed then says, “I want to race in the big race this weekend.”

Now most screenwriters would’ve just cut to the race. That’s what this movie is about right? A guy who’s a racer. Let’s put him in races! But the smart screenwriter understands that it doesn’t make a lot of sense for someone to race when they’ve never even practiced before. In these scenarios, YOU MUST MAKE YOUR HERO EARN IT.

So Speed says to his dad, if I can beat the lap record at the local speedway, can I race? And his dad says sure because, “that’s impossible.” Of course, Speed Racer does the impossible and sets the record. This is standard good storytelling. You can’t hand your hero anything. Make them earn it. Especially if they’re making a big leap in the script.

I also liked the big twist (SPOILERS FOLLOW). I’m not familiar with the Speed Racer show so I don’t know if this was JJ’s idea or not. But I loved that Racer-X turned out to be the dead brother. That moment jolted me out of an appreciate reading malaise and turned the script into something I actually wanted to finish.

Because now I could tell the writer actually cared. They thought about the story. Most writers will just kill off the brother in that opening scene to create sympathy. They don’t think beyond: I NEED TO MAKE MY HERO SYMPATHETIC. To bring that storyline back in a powerful way conveys a way higher desire to tell an enjoyable story.

I think I have a better idea of Speed Racer after this script. I always thought of it is as random weird anime. But now I realize it’s like the car version of Inspector Gadget. The cars can do all these fun things and there’s this deeper sci-fi spy story involved. It’s still going to be a hell of a tightrope to walk tone-wise. But if JJ is heavily involved and doesn’t leave it to one of these dime-a-dozen showrunners, I think it might actually be good. And that’s something I was not expecting to say going into this review.

Screenplay Link: Speed Racer

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The correction of “who” to “whom” is used in a dialogue scene in Speed Racer. You know what? Never use the word “whom.” Between the years 1993 and 1999, everybody was obsessed with the difference between the word “who” and “whom.” It became such an obsession that it began appearing in numerous movie dialogues, including films as big as The Phantom Menace. To this day, these silly debates have rattled, mobilized, and confused people to feel passionately about this debate yet I am here to tell you that “whom” is a stupid word that nobody who isn’t trying to sound pretentious uses and you can literally use “who” in its place every time and no one will care. I’m glad we can all agree on this.