Is Victoria Pedretti our Rosemary?

Is Victoria Pedretti our Rosemary?

I get a lot of e-mails after these Logline Showdowns from writers who are miffed that their loglines didn’t make the big show. While I don’t have time to respond to every one of these inquiries (I can respond to anyone who gets a logline consultation – they’re $25 – e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com), I can tell you why the loglines from this last showdown that did well, did well. And why the ones that didn’t, didn’t. In doing so, I can help you better understand why loglines get picked.

Thanks to Scott, we have a clear breakdown of the voting…

Rosemary: 33 ½ votes (35%)

A prolific serial killer struggles to suppress her desire to kill during a weekend-long engagement party hosted by her new fiance’s wealthy, obnoxious family.

Fear City: 28 votes (29%)

A serial killer has an entire city living in fear – until he is kidnapped by three petty crooks looking to make their big score. The ransom demand they make to City Hall is chillingly simple: “Give us a million dollars or we’ll let him go again”…

Proven: 18 ½ votes (19%)

When three, poverty-stricken best friends attempt to strike it rich by retrieving a dead Bigfoot from a remote river, their plan is endangered by a rapidly rising tide and the team of vicious hunters who killed the beast.

Ninestein: 11 votes (11%)

Scientists attempt to clone Albert Einstein to save the earth from an incoming asteroid, but when the process goes awry they are left with nine clones, each just a fraction as smart as the original.

Olympus Park: 3 votes (3%)

When a naive businessman unveils a theme park of reincarnated historical figures, he must convince a ruthless FBI agent that his attractions are safe when a clone of Elvis Presley appears violent.

Tide Pool: 3 votes (3%)

Two good Samaritans, with their relationship on the brink of collapse, find themselves in a fight for survival while attempting to rescue a juvenile great white shark that has become stranded in a rock pool during low tide.

Rosemary

Rosemary was the very first logline I found in the submissions that I knew would make the Showdown. And, after picking the rest of the loglines, I knew it was the best logline of the bunch. Why was it the best logline? A few reasons. One, loglines tend to pop more when they have irony. You have a serial killer at an engagement party. Serial killers are supposed to slink around the dark rainy streets of the worst parts of town, scouting potential victims. They’re not supposed to be in happy fun places like engagement parties. The serial killer is also a woman, which is not traditional. So that further helps the idea feel different. But the aspect of the logline that puts it over the top are the words “struggles” and “obnoxious.” We’ve all had those dark not entirely authentic thoughts, at some point in our lives, of offing the really obnoxious people we encounter. So to be in a party full of these people? And to have this serial killer act as our wish-fulfillment vessel? Just like that you’ve made your serial killer protagonist sympathetic. It’s, by far, the most clever setup of the bunch. And, if it’s executed well, you’ve got a slam-dunk movie on your hands. We’ll find out tomorrow if the execution is as strong as the logline when I review the script.

Fear City

Fear City was the sexiest concept of the bunch. So I knew it was going to do well. It had that big flashy “high concept” pitch that more writers used to know how to construct during the days of weekly million dollar spec sales. However, I understand why it lost to Rosemary. The logline isn’t nearly as elegant. You’ve got two sentences instead of one. While it’s not required that your logline be only one sentence, the best writers tend to know how to distill their idea down to one sentence. I definitely feel that those two sentences gave the logline a slightly clunkier feel, which I can attest to personally since I had to read it twice to make sure I got it. Without fail, whenever a logline is clunky, the script is clunky as well. So there may have been some hesitation to vote for the script for that reason. I might still review the script at some point and be proven wrong. We’ll see.

Proven

Proven was the biggest wild card of the bunch. I knew that Rosemary and Fear City were probably going to beat it but I didn’t know where it would land in the remaining four. I do think you get a leg up in your concept if you’re dealing with these popular culture legends. Bigfoot. Atlantis. The Bermuda Triangle. The Loch Ness monster. They’re IP-gold. They give your concept an immediate shine. But as I told the writer via e-mail, it’s a tough sell to build your movie around a dead Bigfoot. He’s such an iconic figure that when you present a story around him that provides no hope – he’s dead and that’s it – a portion of your potential audience won’t be onboard. The writer was adamant that doing so wasn’t right for his movie (he pointed out that there’s a dead young boy in Stand By Me and we went along with it) and I respect every writer’s right to write the story they want to write. But I suspect that if there was a twist, after they pick up Bigfoot, that he’s actually clinging to life? And that their initial motivation – to make money off the dead body – changes to trying to save its life? That this logline would’ve won the competition. Feel free to offer your thoughts on whether I’m right or wrong in the comments!

Ninestein

Ninetstein was my little underdog pick for the Showdown. When it comes to comedy loglines, you want the reader to physically laugh when they read your logline. And that’s exactly what happened in the case of Ninestein. But my big fear was that Ninestein was an idea that only worked as a logline and not as a movie. Which I noticed several of you picked up on. Cause when you think about it, how do you create 9 dumbed-down Einsteins that are all unique? Usually in these “multiple versions of the same character” movies, there’s one super dumb version. But here, you’d need nine super-dumb versions, and then you’d need to somehow make them all different form one another. I just don’t know how you do that. I’m still curious about this logline though and I may review the script at some point.

Olympus Park

I went back and forth about whether to include Olympus Park. The writer’s been persistent but never annoying, which is something I admire. And there is something potentially interesting about a park full of cloned historical figures. But the reason I’ve resisted this logline for so many other showdowns is because of the Elvis part. As soon as Elvis is mentioned, the reader has a big fat “WTF??” reaction. As tons of you have pointed out, it’s a bizarre non-sequitur that feels disconnected from the first part of the logline. Why not have Genghis Khan go crazy? Isn’t that a much more logical conflict? I sensed that the writer was going to get beat up on that and he did. I noticed that he’s since stated that focusing on Elvis in the logline was a mistake because the story is more nuanced than that. But I don’t know. I still think he’s taking a fun idea and not focusing on the right elements to bring out that fun. Which is what all of us should be doing. When we come up with a fun idea, ask ourselves how to best take advantage of that idea.

Tide Pool

The reason I picked this logline was three-fold. One, sharks always sell. They will never stop making shark movies. Two, the writer was doing something different with his shark concept. And three, I liked the irony. Instead of trying to avoid a shark, we’re trying to help a shark. With all that being said, I knew this was going to finish last for several reasons. One, can we please stop capitalizing words that don’t require capitalization (Samaritans). That’s a huge red flag right there. Two, it sounds like we have a kid shark here? In other words, you’ve made your shark *less* dangerous? That’s typically not a good strategy when coming up with a movie idea. Third, a lot of you pointed out this was happening in a little miniature pool, giving it a very low-stakes feel. And finally, it’s not clear why they’re in a fight for survival. I’m not even clear on if this shark is dangerous since it’s a young and, therefore, smaller shark. It also sounds like it’s easy to stand in this area? So wouldn’t maneuvering away from the shark be easy? I could keep going. But the point is, when this many questions pop up during a logline, potential readers end up bailing. Their attitude is, “If you can’t even be clear in a 30-word logline, why would I expect you to be clear telling a 20,000 word story?” This is why it’s so important to get feedback on your loglines because people like me can tell you this before you burn opportunities!

So what are the lessons learned today?

- Irony is your friend when it comes to loglines.

- The sexier the concept, the more people will overlook the weaknesses in your logline.

- When it comes to beloved anything (in this case, Bigfoot), the audience wants there to be hope involved.

- Beware of loglines that work great as loglines but start to break down when imagined as movies.

- Avoid pulling plot points out of left field. Just cause it makes sense to you doesn’t mean it will make sense to others. Get feedback so you know it makes sense!

- If you have a dangerous and, therefore, compelling situation, don’t look for ways to make it less dangerous.

I will see you back here tomorrow for my script review of winning logline, Rosemary!!!

NEXT LOGLINE SHOWDOWN

The next Logline Showdown is happening on Friday, March 24th. If you want to enter you need to get me your loglines by Thursday, March 23rd, 10pm Pacific Time.

Send me: Title, Genre, Logline

E-mail: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Rules: Script must be written

Deadline: Thursday, March 23rd, at 10pm Pacific Time

Cost: Free

GET A PRIVATE SCRIPT CONSULTATION FROM CARSON!: Don’t like the idea of your logline or script being reviewed by the public? Get a private consult with me! I consult on loglines ($25), feature screenplays ($499) and everything in between. If you’re unsure what it is you need, e-mail me. I’ll answer everything you want to know and help you come up with a consultation that works for you. Just this past week I consulted on a synopsis, an outline, a first act, and a writer who sent me five loglines and wanted to know which one he should write as a script! So there’s a lot of flexibility if you need advice. You can set up a consult with me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com.

Genre: Satire/Comedy

Premise: Shunned by elite society as a member of the gig economy, a sociopathic dog walker infiltrates an exclusive L.A. community with designs of reaching the top of the neighborhood’s social ladder.

About: This script finished in the top 10 of last year’s Black List with 20 votes. This appears to be the brothers’ first big screenplay.

Writers: Briggs and Wes Watkins

Details: 100 pages

Lili Reinhart for Dylan?

Lili Reinhart for Dylan?

A few people told me this wasn’t very good. But it does come from a sub-genre that I like. So we’ll see what happens. Oh yeah, a quick note. This script has a lot of twists and turns. It is best enjoyed reading it yourself rather than reading my synopsis. Because my synopsis WILL reveal spoilers.

24 year old Dylan is squatting in a Hollywood apartment, not doing anything with her life that I could discern other than her hobby of sneaking into rich peoples’ houses and pretending that she lives there until the owners come home and she has to sneak out.

One night, while hanging out in a Beachwood house, a dog-walker comes in and catches her there. The dog-walker doesn’t report her though. Instead, she tells Dylan that if she wants to sneak into peoples’ houses, she should walk dogs.

This is a lightbulb moment for Dylan, who immediately visits a dog park the next day and notices a beautiful woman named Jessica walking an even more beautiful dog. Jessica’s dog is the clear star of this dog park and so Dylan tries to befriend her to see if she can work for her.

When Jessica blows her off, Dylan follows her up to a Griffith Park hill trail, kills her, then kicks her dead body over the cliff. She takes the dog, heads back to the owners home, and informs the couple living there, Shira and Jacob, that Jessica has moved on and she will now be walking the dog.

Dylan does this for a while until the dog attacks and nearly kills another dog who happens to be walked by… the very girl who caught her in the first house and told her about this whole dog-walking gig. Dylan makes a run for it but eventually, our initial dog-walker, whose name is Anna, finds her.

She makes casual chit-chat with Dylan BEFORE KILLING HER!!! That’s right. Another murder. Who wrote this? Bing ChatGPT? And we’re only on page 45! With Dylan now dead, we start following Anna, who wants to do what Dylan was doing who wanted to do what Jessica was doing.

Anna makes friends with some other dog-walkers but when they suspect that she may have some information on the death of Jessica, she goes into self-preservation mode. She then makes a bold move, blackmailing Shira and Jacob, knowing that if they don’t consider her dangerous, she’s done. Will Anna’s plan work? Or will she end up like her predecessors?

In the words of the great Iggy Pop, “I’m a real wild one. And I like a wild fun. In a world gone crazy. Everything seems hazy. I’m a wild one. Oh yeah, I’m a wild one.”

This was a wild one, folks.

I’m still not even sure what I read. But I wouldn’t call it un-entertaining. Maybe uneven.

Whenever you’re trying to write sophisticated satire – which I’m pretty sure is what this script is – you have to be smarter than everyone in the room. There can’t be any clunky moments or frayed edges. We really have to feel, as the reader, that you are in total command of this commentary.

I didn’t feel that way. It started with the opening page.

The “whatever” is unnecessary. “Green as cash” is not a great visual simile. The road “slims and winds.” “Slims” is an awkward word to use there. Hidden behind walls of “Indian Laurel.” I don’t know what that means. Is there a famous Indian girl named Laurel who’s cloned herself and stands outside every house in Beachwood? “Gain a zero on their price tags” is an, arguably, try-hard line. “As we smear by them” is a strange description. I have to strain to imagine it.

I’m probably being too hard on this page but it definitely prioritizes style over clarity and that’s something I never endorse. Clarity must always come first in screenwriting. So, right from the start, I was wary.

Another problem is that I could never figure Dylan out. Since her whole life was a lie, I didn’t have anything to grab onto, relate to, or care about. There was so much distance between me and her that I never felt close enough to her story.

Why is she doing this? Where did this compulsion come from? Why is she squatting around in Hollywood and sneaking into peoples’ houses? We don’t know. We’re asked to buy that at face value and that’s not how storytelling works. We have to know why humans are doing the things they’re doing in order to become invested and interested.

A good example is the movie, Emily The Criminal. In that screenplay, the writer makes sure to take us through Emily’s struggles of trying to get a job, subsequently working a job she hates. So that when she’s given this opportunity to make money by stealing, we know why she’s doing it.

Meanwhile, I barely know Dylan and, out of nowhere, she kills this dog-walker and kicks her off a cliff and I’m just supposed to go with it?

Of course, I eventually realized why this was the case. Dylan wasn’t written to make it through the story. She gets killed. Which was a huge shock. But it would’ve resonated more had we felt some attachment to her.

To the Watkins credit, there’s some fun stuff going on here with the way the characters feed into the story. We meet this random dog-walker in that opening scene – the one who catches Dylan in the home, then we forget about her. Only to meet her again, 50 pages later, and then she becomes the main character.

Dylan also meets this character named Noah in the dog park early on the story. He disappears. But then, when Anna takes the lead role in the story, she meets Noah as well and also befriends him. So it was cool how these characters were woven into this weird tapestry of a screenplay.

But I just don’t know what to make of this thing. There are so many creative choices that make you go, “hmmmmm….” There’s an entire scene dedicated to expressing a dog’s anal glands in front of a small audience that felt more like it belonged in a 1998 Farrelly Brothers movie than in this sophisticated satire.

And then there are only really short dialogue scenes the whole movie before 80 pages in where we get this gigantic six page dialogue scene that comes out nowhere. Some of you might not think that’s a big deal. But screenplays have a rhythm. And if you establish that rhythm only to completely upend it, it’s jarring. The reader isn’t sure what to make of it.

However, I will say this. This script is the most unpredictable script in the Top 10 of last year’s Black List. It’s weird. It’s kinda fun. Even though it has problems, it does leave an impression on you. For those reasons, I think it’s worth reading.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I like when writers keep their character in a state of desperation. It forces the character to constantly act and solve problems, which often results in interesting dramatic situations. Just as Dylan gets the dog-walking job with Jacob and Shira, she gets kicked out of the apartment she’s squatting at. So now she doesn’t have any place to live. This places a question in the reader’s mind – What is she going to do now? – that compels them to keep reading to find out the answer. If she never would’ve gotten kicked out, that’s one less reason to care what happens next.

Today’s big 90s spec sale is part The Fugitive, part Shawshank, and part Hell or High Water.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a daring prison break, a bank robber forced to work with two problematic fellow prisoners, heads back to his home town to make things right.

About: Shout out to Scott for making me aware of this one. The script sold in 1995 for 600,000 against 1 million. It was written by Ken Nolan, who penned Black Hawk Down and Transformers 5. The movie looks like it was shelved once competing rain project “Hard Rain” rained on its parade. Blame it on the rain. I swear, I have to reign this lame rain jokes in. Rain or shine, I can’t stop using them.

Writer: Ken Nolan

Details: 127 pages

Henry Cavill is looking for a new job, right?

Henry Cavill is looking for a new job, right?

One of the most common fears we screenwriters have is that while we’re dutifully writing our latest screenplay, a movie with a similar concept will get released and our script becomes irrelevant.

It’s a legitimate concern and the reason today’s script never got made, despite selling for so much money. Another rain-centered crime movie, Hard Rain, made it to theaters first, taking all the wind out of “The Long Rain’s” sails.

The reason this happens so often is because we’re all pulling water from the same well. And so while we may think we’re original, the reality is, that idea we came up with four months ago was inspired by the same set of news stories that tens of millions of other people saw.

I still remember a few years back, there were not one, not two, but three separate projects purchased that were focused on a peeping tom motel situation. If you did the math, you went back about 5-6 months and learned there was an article in a major publication about this peeping practice.

In other words, a bunch of people saw the same article and a percentage of them, who were screenwriters, thought, “Ooh, that would make a good movie.”

This is why I encourage writers to avoid coming up with movie ideas inspired by popular culture or current news stories because you’re choosing to compete with the highest number of writers whenever you do that. It’s better if your idea comes from real life experience or something random you encounter that very few people are aware of.

One of the reasons Tarantino is considered to be such a unique artist is because all of his ideas come from updating obscure old movies that not many people know about. So he’s not going to have a lot of competition for those ideas.

Anyway, I barely remember Hard Rain. What I do remember is that it had a fun trailer. Will The Long Rain offer more than that?

Nick True is in Mississippi prison for something. We don’t know what yet. On this particular night, the prison is being flooded with nonstop rain. It gets so bad that the guards have to chain all the prisoners up (three people to a chain) and place them outside so they don’t drown.

Nick, who often offers us deep thoughtful narration about life and imprisonment, is chained to a couple of sketchy dudes, TEE-VEE and Preacher Willie. As the little outdoor corridor they’re in also starts to badly flood, they rebel, and soon The Nick True Trio makes a boop-bop skedaddling run for it.

They somehow scale three fences and run into the rainy night. They’re able to make it to a barn, where they dry up. But then in a really random coincidence, the cops find them, and they’re on the run again. The rain still hasn’t stopped, by the way.

While they’re on the run, we start flashing back to how Nick ended up in prison. He was with the love of his life. They were going to have a fairytale ending. All Nick had to do was rob a bank first. Cause fairytale endings need money in America.

Obviously, the robbery goes badly. But even worse, Nick’s own brother deceives him in the worst way. Nick ends up losing his girlfriend and his brother. AND he ends up in prison. Hat trick on why crime doesn’t pay, Nicky.

But this prison break, along with all this rain, has given Nick a second chance. You see, that money he stole from the bank is still out there. He hid it. So if he can get it back, he just might be able to reboot that fairy tale.

Man, talk about a script that’s of its time. This screenplay couldn’t have been more 90s if Kurt Cobain scored a Youtube accompaniment for it. “Here we are now! IT IS RAINING! Is that Tommy Lee Jones? Or Morgan Freeman!??” (If you sing that to the tune of Smells Like Teen Spirit, it makes sense, I promise)

Whenever you start reading a script, one of the first things your mind does is attempt to figure out what kind of movie you’re watching. Once you understand the template, you know what to expect for the most part and you can settle in and enjoy yourself.

But what happens when the script doesn’t announce what it is? If you don’t make that clear, you can expect a lot of reader frustration. And I wasn’t clear on what this was. The script starts off with a really fun opening prison break scene where the characters are chained up together.

This is how you make things different. Everybody says, “Everything has already been done before.” And that’s true. There have been a million prison-break scenes. But I don’t remember any with three people chained up to each other. Any recently, anyway. That creates all sorts of new obstacles the writer can play with to write some creative scenarios.

This is followed by our characters hanging out in a barn where they get their bearings. The next day, the cops accidentally run into them and they’re forced to shoot a cop and steal his car. A helicopter drops down out of the clouds and starts chasing them.

They get to a bridge, which they shoot off into a raging river. And then, while they’re being pulled down the river, we jump backwards in time and cover how Nick ended up in prison, which was that he robbed a bank. This is a long slow flashback.

Then we’re back in the present again. Then the past. Then the present. Then the past. And things just sort of feel disjointed. It’s an “on-the-run” movie. No it’s a heist movie. No it’s a slow introspective character piece. Throughout all of this is this deep voice over from Nick where he ponders life. What is this thing? It’s like a Frankenstein script.

But then, somewhere around page 65, it picks a lane. We find out through the flashbacks that the money he stole from the bank robbery, he hid. Which means it’s still out there. And he’s going to get it.

It was an interesting moment when this plot beat entered the story because I immediately noticed I was more interested in what was happening. Was it just that plot point that pulled me in? No. The thing that changed it all is that NICK ALL OF A SUDDEN BECAME ACTIVE. Instead of being “the guy on the run,” he became “the guy with a plan.”

That’s a great screenwriting lesson. For the first sixty pages, I’m sitting there wondering when’s the “point” going to kick in? But my dissatisfaction was more likely coming from the fact that the main character wasn’t an active participant in the story.

This is one of the unheralded screenwriting power moves in The Fugitive, and one of the main reasons it works so well. Richard wasn’t just running from the police. He was trying to solve his wife’s murder. If he’s just running from the police, he’s reactive the entire movie. But if he’s trying to solve a murder, he’s active.

That change in The Long Rains saved the script. And then Nolan kicks things up a notch with a great climax. It’s definitely not a perfect screenplay but Nolan does a good job sneakily setting up the real story he wants to tell throughout the first half. Once he gets to tell that story, the script comes alive. Check it out yourself!

Script link: The Long Rains

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script taught me that you can make things a lot more interesting for your smart main character by handicapping them. In this case, you stick him with two dumb people. Cause now, “stupid” enters into the equation sometimes, and the stupid moves lead to more interesting scenarios than the smart moves. For example, TEE-VEE can’t swim, so when they’re stuck in the raging river, TEE-VEE is practically ripping Nick apart to stay afloat, even though, by doing so, he’s ensuring that both of them will drown. So now Nick has to figure out a way around that. That scene doesn’t exist if Nick escapes prison on his own. So always look to handicap your heroes!

How a screenwriting fatal flaw is silently killing all the latest Marvel movies.

Ant-Man crept over 100 million dollars for the 3-Day weekend (104 mil), saving a little bit of face, but not much (Black Panther 2 opened to 181 mil, Thor Love and Thunder to 144, Doctor Strange 2 to 187, and Spider-Man No Way Home to 260).

I was fully intending on seeing this movie. I love Ant-Man. I like Paul Rudd. I thought the first movie was clever and gave us something new. The character of Ant-Man himself is fun. His powers are weird in cool ways (he’s Ant-Man but he can turn giant??).

But leading up to this movie, I couldn’t escape all the bad buzz surrounding the film. I kept hearing troubling things about the storytelling. That it wasn’t really about Ant-Man. It was about his family. It was about Kang. They even made way for introducing one of the strangest characters in the Marvel Universe – something called “Modoc.”

I have a question. Why are you making movies that don’t prioritize your main characters, Marvel? The answer to that question is both a window and a mirror. It’s a window into the mind of Kevin Feige, the head of Marvel, and a reflection of the franchise’s current priorities.

The movies are no longer about the main characters. They’re about everything surrounding those characters, as well as what’s going to happen NEXT, in future Marvel movies and TV shows. You came to this movie to be entertained now? F U. You have to see the next three Marvel movies if you want to be satisfied.

Marvel may think this strategy is a winning one. But I’ve paid to see nearly every Marvel movie in theaters. The only two I didn’t were Thor 2 and Eternals.

So it says a lot that, despite being a character I enjoy, that this movie wasn’t worth my time. And if I – someone whose entire life exists around movies – wasn’t interested, you can bet your bottom dollar that a lot of casual moviegoers are feeling the same.

Four of the last five Disney-Marvel movies have received an RT score of under 75%. Two of those (Ant-Man 3 and Eternals) were under 50%. Contrast that with the five before that, none of which were lower than 75%. Clearly, the quality of these movies is dropping. And it doesn’t look like it’s going to get better. The Marvels (the Captain Marvel sequel) just got pushed back six months with rumors swirling that it’s unwatchable.

Why does this matter? Because Marvel is the movie business right now. It’s holding up the entire tent. If it crumbles, there goes the circus. And the way this relates back to Scriptshadow is that Marvel has embedded a screenwriting fatal flaw into all of its latest movies. For whatever reason, they are unaware of this blind spot. And if they don’t turn their head and see the car in the other lane soon, they’re headed for one of those Chips-level pile-ups.

Yes, I just referenced Chips. It’s Monday. Anything can happen.

So what is this flaw?

The best screenplays are simple stories told well. Clean narratives. Clear goals. Clear motivations. A limited number of characters so that the script has time to imbue those characters with adequate flaws that can be explored and resolved. It’s no accident that the best comic book movie of the last five years – Joker – used this template to a T.

Do you guys remember the first Spider-Man franchise with Toby McGuire? The first film was good. The second film was even better. And the third film was trash. Do you remember why that film was trash? Because they famously tried to do too much. Too many villains. Too experimental (I think at one point there was a musical number). Narrative was all over the place. That movie was the epitome of what happens when you try to overstuff a screenplay.

I guess that movie has now been memory-holed at Marvel. I don’t think they’re aware it exists. Because the original Spider-Man 3 has, inexcusably, become the template Marvel now uses to write their movies.

But Carson, what about Spider-Man No Way Home? That had a bunch of characters in it and it worked. True. I’m not saying the strategy can’t work. I’m just saying it’s way harder to make work. So, if you’re going to use it, you need to take the extra time required to get the script right.

This is not rocket science. If you have ten storylines in your screenplay instead of two, you will need more time to write those storylines! This is exactly what James Gunn has been saying as he ramps up DC Studios. We’re going to take that extra time and get the scripts right. The Flash looks really good even though it has a lot of stuff going on. Not coincidentally, I’ve heard that they worked crazy hard on that screenplay.

Dr. Strangelove 2 was awful. Thor Love and Bananas was awful. Ant-Man Quantum-shame-on-ya looks awful. No offense, Kevin Feige, but get your sh— together, man. What are you doing?? You’re cranking out garbage and, in doing so, you’re damaging your brand. Every Ant-Man 3 you put out makes us less confident in the next Marvel movie.

The simple truth may be that Marvel doesn’t have any stories left to tell. There have been 30 of them. Star Wars couldn’t even come up with 6 good movies. Marvel is telling three times that many and reached the point where, maybe, it can’t tell simple stories anymore. The audience wants something new, wants something different. But what if there’s nothing different left?

When you don’t have a good story to tell, you rely on gimmicks. For the regular screenwriter, gimmicks are things like writing your screenplay in the first person, or throwing a couple of forced twists in the middle of your story (the main character dies!).

For the Marvel screenwriter, gimmicks are including X-Men and Fantastic Four characters from other dimensions (Dr. Strangelove 2), or prioritizing a shocking post-credits scene over the movie itself (Eternals). Those sorts of things can be fun. But if they become more important than writing a great movie, that’s when you get into trouble. And it seems like Gimmick writing is the new strategy over at Marvel.

Cameos like this have taken precedence over dramatically compelling plot developments.

Cameos like this have taken precedence over dramatically compelling plot developments.

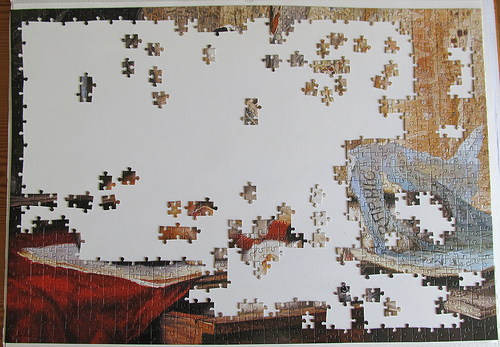

The more I break screenplays and movies down, the more I realize how hard screenwriting actually is. It’s a lot like those sophisticated puzzles you used to do which had 2000 pieces. A puzzle like that takes serious amounts of time. You need to really sit there and sift through the pieces and try combinations to see if they fit, and do that day after day after day.

Then, once you get that outside edge of the puzzle figured out, you could keep filling in and filling in and filling in, until you finally put the whole thing together. Marvel movies feel like they stop working on the puzzle before that middle section is finished. The edge is in place. But the middle is still a murky mess. There are a few clumps of pieces that go together which are vaguely tossed in the middle. But it’s not enough to know what you’re looking at.

Dr. Strangelove 2 was one of the sloppiest big budget movies I’ve ever seen. And it’s because it was such a mess that when I heard even the slightest bit of rumblings about the writing in Ant-Man 3 being weak, I was out. Because I had recent proof that Marvel was getting lazy and making bad movies.

If they want to play this game where launching some dumb character named Ironheart is worth messing up the flow of their entire second act for (Black Panther 2), godspeed to you. Do that. But I’m warning you. Prioritizing the wrong things in storytelling has consequences. You did it in Dr. Strangelove 2. You did it in Black Panther 2. Now the critics are onto you. They’re not giving you breaks anymore, which is why you pulled a sub-50% RT score and the second ever “B” cinemascore for a Marvel movie. The Marvel fanbase is more forgiving. But believe me, they *will* eventually turn on you if you keep this up.

Last month, Call of Judy dominated the competition!

This month, a new logline will rise to the top. And with it, a new legend will be born. Or they’ll get a “wasn’t for me” and we’ll forget about the script a week later. One of the two!

Every second-to-last Friday of the month, I will post the five (or six??) best loglines submitted to me. You, the readers of this site, will then vote for your favorite in the comments section. I then review the script of the logline that received the most votes the following Friday.

If you didn’t enter in time for this month’s showdown, don’t worry! We do this every month. Just get me your logline submission by the second-to-last Thursday (March 23 is the next one) and you’re in the running! All I need is your title, genre, and logline. Send all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

Also, this is a reminder that a lot of your are shooting yourselves in the foot with your loglines. You’re making catastrophic mistakes (clunky phrasing, being too vague, overwriting, not adding that ‘must-read’ climax finisher to your logline) that give you no shot at script requests. It genuinely hurts me to see because you may have a good script but nobody’s going to want to read it until you’re able to properly write a logline for it. If you want a logline consult with me, they’re cheap – just $25. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

Are we ready? Voting ends Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time!

Good luck everybody!

Title: FEAR CITY

Genre: Thriller

Logline: A serial killer has an entire city living in fear – until he is kidnapped by three petty crooks looking to make their big score. The ransom demand they make to City Hall is chillingly simple: “Give us a million dollars or we’ll let him go again”…

Title: Tide Pool

Genre: Thriller

Logline: Two good Samaritans, with their relationship on the brink of collapse, find themselves in a fight for survival while attempting to rescue a juvenile great white shark that has become stranded in a rock pool during low tide.

Title: PROVEN

Genre: Coming-of-age Thriller

Logline: When three, poverty-stricken best friends attempt to strike it rich by retrieving a dead Bigfoot from a remote river, their plan is endangered by a rapidly rising tide and the team of vicious hunters who killed the beast.

Title: Ninestein

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Scientists attempt to clone Albert Einstein to save the earth from an incoming asteroid, but when the process goes awry they are left with nine clones, each just a fraction as smart as the original.

Title: Olympus Park

Genre: Sci-fi

Logline: When a naive businessman unveils a theme park of reincarnated historical figures, he must convince a ruthless FBI agent that his attractions are safe when a clone of Elvis Presley appears violent.

Title: Rosemary

Genre: Horror/Dark Comedy

Logline: A prolific serial killer struggles to suppress her desire to kill during a weekend-long engagement party hosted by her new fiance’s wealthy, obnoxious family.