I suspect most of you will assume I didn’t like The Bubble. Most of you would be correct. However, I don’t think The Bubble is as bad as some people are saying it is. Once it hits its groove and understands what it is, it’s not bad. The problem is it takes too long to get there.

I suspect most of you will assume I didn’t like The Bubble. Most of you would be correct. However, I don’t think The Bubble is as bad as some people are saying it is. Once it hits its groove and understands what it is, it’s not bad. The problem is it takes too long to get there.

The movie starts off as a commentary on the pandemic, which doesn’t work because while the intention was to parody something we all went through and therefore be “relatable,” it only parodies a unique subset of the pandemic – that of trying to make a movie.

I don’t know anyone who had the problem of being quarantined in a hotel with a bunch of charismatic people while they got paid millions of dollars. It was too specific of a parody so many of the pandemic jokes didn’t work. For example, I didn’t have to get tested every other day during the pandemic. So that’s not funny to me.

However, once the narrative shifts to the studio trapping the actors until they finish their movie, the movie actually gets kind of funny. For example, there’s this big climactic scene where the actors make a run for it and get into a helicopter, which is their only way to freedom.

In every action movie, getting in a helicopter and flying off while being attacked from all sides is a foregone conclusion. But in this movie, where a lone actor knows how to fly helicopters via his 8 movie-prep lessons, the team rises off the ground before they find out that the actor has only ever learned how to go up and down. So the big climactic moment is simply: can he figure out how to go forward so they can leave?

Despite its weaknesses, it’s a movie worth discussing if only because Judd Apatow is the biggest comedy director in the world. So if Judd Apatow miscalculates, it’s worth asking why, so we can learn from it.

Judd made two risky choices that may have done The Bubble in. The first is that he abandoned any emotional through-line in the screenplay, which has been one of his staples. For example, in his last film, The King of Stanten Island, there’s this really deep surrogate father-son relationship between the main character and his mom’s new boyfriend.

As I’ve argued many times here on the site, if we don’t feel any emotional connection to the characters, we don’t feel like they’re real. So when they get into trouble, we don’t fear for them. And without that fear, every joke that highlights their misfortunes is paper-thin, since we know it doesn’t matter.

Judd has been forthright about this. In his Barstool Sports interview, he said that this was a new challenge for him, writing a pure comedy, where all you care about is the jokes. I got the sense that he began freaking out about this choice towards the end of the movie as the sudden third-act focus on character emotion felt like an overcorrection, an attempt to remedy his mistakes from earlier.

The other mistake Judd made was he didn’t have a main character. I remember about 30 minutes into the movie feeling like I’d met 50 people and knew none of them. We’re bouncing around so much that we never get attached to anyone. If you look at Judd’s most popular movies – films like The 40 Year Old Virgin, Knocked Up, even Trainwreck – they’re almost aggressively one-character movies.

When you focus on one character, you can dive into who that person is, what makes them tick, what their flaws are, what their vices are, what their relationships are like. And we just didn’t get any of that in The Bubble.

There’s a moment late in the script where the closest thing that Judd has to a main character, Carol (Karen Gillan), seeks out help from Sean Knox (Keegan-Michael Key). In the scene, Carol, who’s losing her mind, wants to know how Sean, who’s a major movie star, is able to stay so positive.

This was about 80 pages into the screenplay, mind you, and it was THE FIRST TIME I was aware that Sean Knox was a major movie star. I had no idea. That was par for the course here. This choice to follow everyone instead of someone prevented us from knowing anyone.

Here’s a tip. Whenever you’re trying to decide who your main character should be, ask yourself who has the most to lose? Who has the most on the line? That person should probably be your hero.

In Juno, it isn’t Juno’s boyfriend who has the most on the line. It isn’t her parents. It isn’t her friend. It isn’t even the family she’s going to give the baby to. It’s her. She has the most on the line. She’s pregnant. What she does affects, literally, the rest of her life.

To that end, the main character in The Bubble probably should’ve been the director, Darren, played by Fred Armisen. He seemed to have the most to lose. This was his big studio shot and it just happened to come at the most restrictive time for movie production in history.

Trying to make a good movie under those conditions must have felt like an insurmountable task. But since we only kind of knew Darren, we never felt any compassion when the movie began slipping through his fingers.

Comedy continues to be an extremely frustrating genre. How is that a genre whose faults are the easiest to dissect is also the hardest to execute?

Luckily, The Bubble isn’t the only new thing that dropped last week. We also got a new Marvel series, Moon Knight. I’d say, of the five Marvel shows that have come out so far – Wandavision, Falcon and Winter Soldier, Hawkeye, Loki, and now this – it’s probably the most anticipated considering it has the best actor and the least known story. Unlike the other shows, Moon Knight is a brand new character we haven’t met before. It’s exciting having a complete unknown for once.

The thing I will give Marvel is that between Wandavision, Loki, and now this, they are taking chances. I can’t sit here and complain that Hollywood never takes risks then ignore it when they do.

I have a lot of admiration for Marvel using these shows as a testing ground for unique storytelling, and not just making them bite-sized versions of their movies. Well, I guess Hawkeye and Winter Soldier are bite-sized versions. But three of these shows are still unique. And Moon Knight may be the most unique of all.

At the center of the story is this giant mystery. This museum worker, Marc, constantly blacks out, missing huge chunks of his life, which results in a daily routine where he’s just trying to get up to speed half the time. For example, a female co-worker asks him if they’re still on for their date Friday night. Except Marc does not remember asking this girl out.

These missing chunks of time are getting more volatile, though. Marc will find himself in the middle of a small village in a completely different country surrounded by cult-members and have no idea how he got there. When they sense Marc is an intruder, they attack him, only for Marc to black out, and when he regains consciousness, 20 people around him have been violently killed, and his hands are dripping with blood. This cult leader, Arthur, wants something Marc has, an Egyptian gold scarab (our macguffin), and he’ll do anything to get it.

The pilot is a great reminder of how influential POV (point-of-view) is to a story. Take The Bubble, for instance. The POV was 20 different characters. We saw the unfolding drama through enough eyes to get a 10,000 feet high look at what was happening.

Here, the POV is just one person, Marc. And because we’re in his head with him when these chunks of time keep disappearing, we feel the same fear he does. I remember, at one point, literally wondering, “Good God. Is this what being crazy feels like? Where you’re a slave to this illogical sequence of events that are constantly changing?” I don’t have that feeling without Marc’s singular POV.

Imagine if Moon Knight was told like The Bubble, where we saw Marc’s situation through ten other people. All that fear would be gone. Cause we’d know exactly what was happening. So POV is something every writer should consider when writing a script. WHO has the POV and HOW MANY people have the POV will have a dramatic effect on character, plot, theme, how you build suspense, where you find your conflict, everything.

The question will be, can Moon Knight keep its death-defying pace up? Presumably, our main mystery will be solved going forward. They already kind of answer it at the end of this episode. So will they simply move the mystery over to his Egyptian roots and what this Arthur villain is after? Or will they just have Moon Knight solving crime, a la Batman?

It’d be a shame if that were the case but this has been my issue with the 6-8 episode format, in general. It’s not quite a TV show. It’s not quite a movie. So nobody really knows what to do with it. We’re in that experimental phase and, so far, I’m not sure I’d call the phase a success. The only high-profile show I’ve seen nail it so far has been Peacemaker.

But I’m rooting for Moon Knight. It’s probably one of the coolest superhero costumes I’ve ever seen. And who doesn’t want to see more Oscar Isaac? Have you seen either Moon Knight or The Bubble? Let me know what you think!

A storyline that got overlooked at the Oscars due to Slapgate was that Apple, not Netflix, took home the first ever Best Picture Oscar for a streaming service! You cannot begin to comprehend how angry this makes Reed Hastings, who has invested truckloads of money coveting high profile directors like Alfonso Cuarón and David Fincher, in hopes of winning that golden statue and legitimizing Netflix. I can only imagine how angry he is that streaming whipping boy, Apple, won their version of the space race.

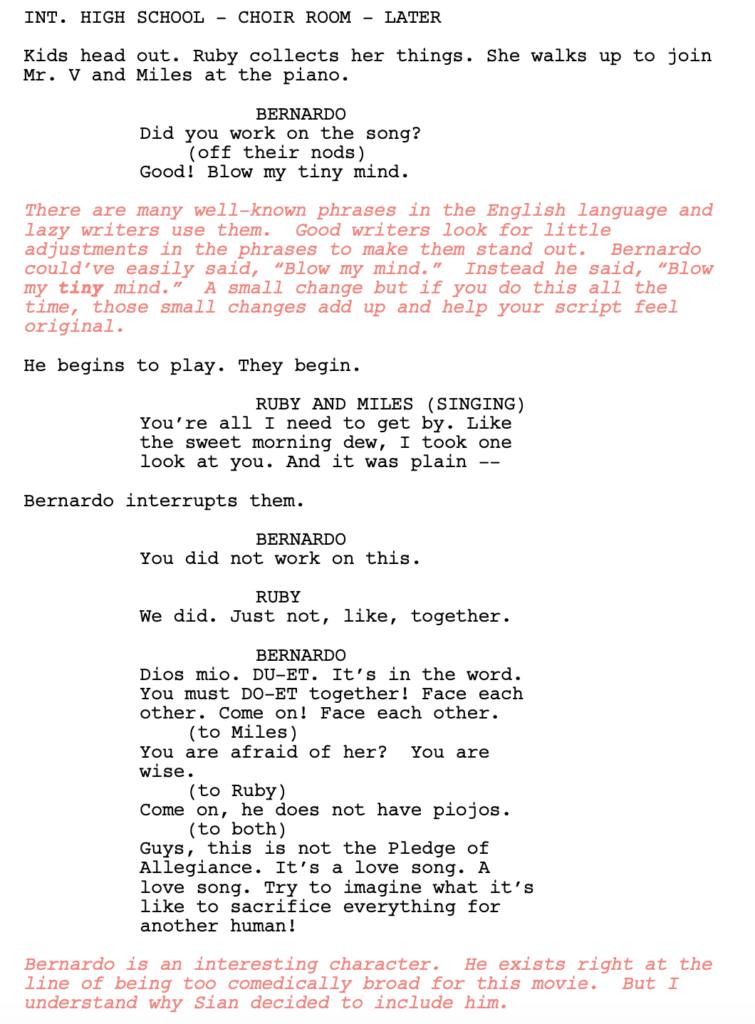

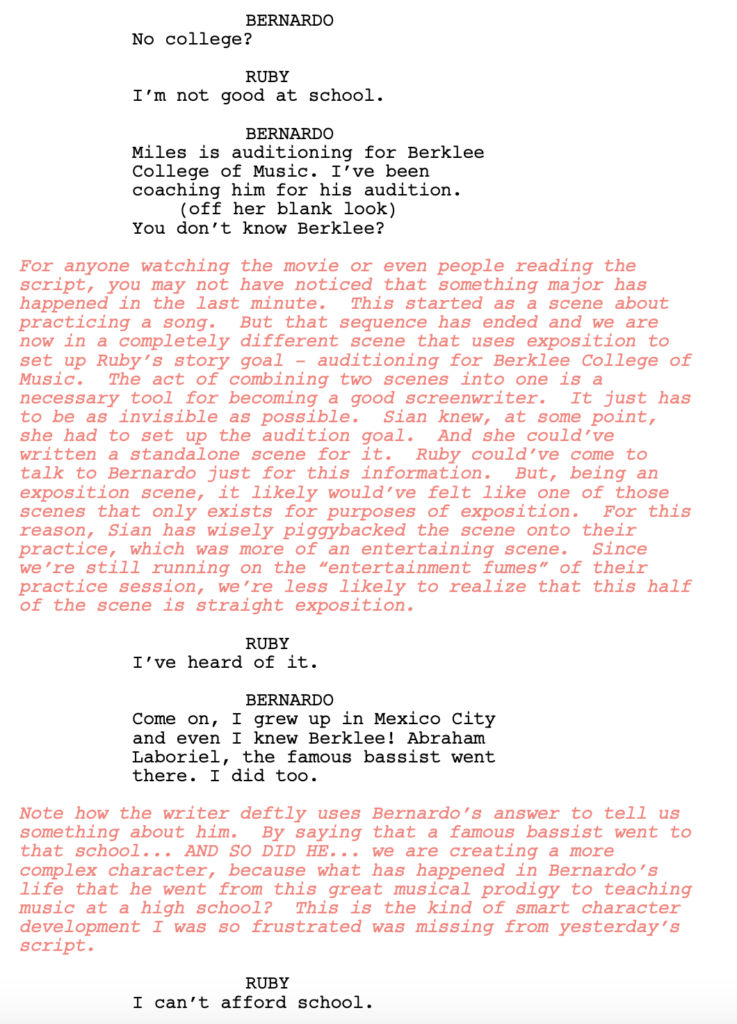

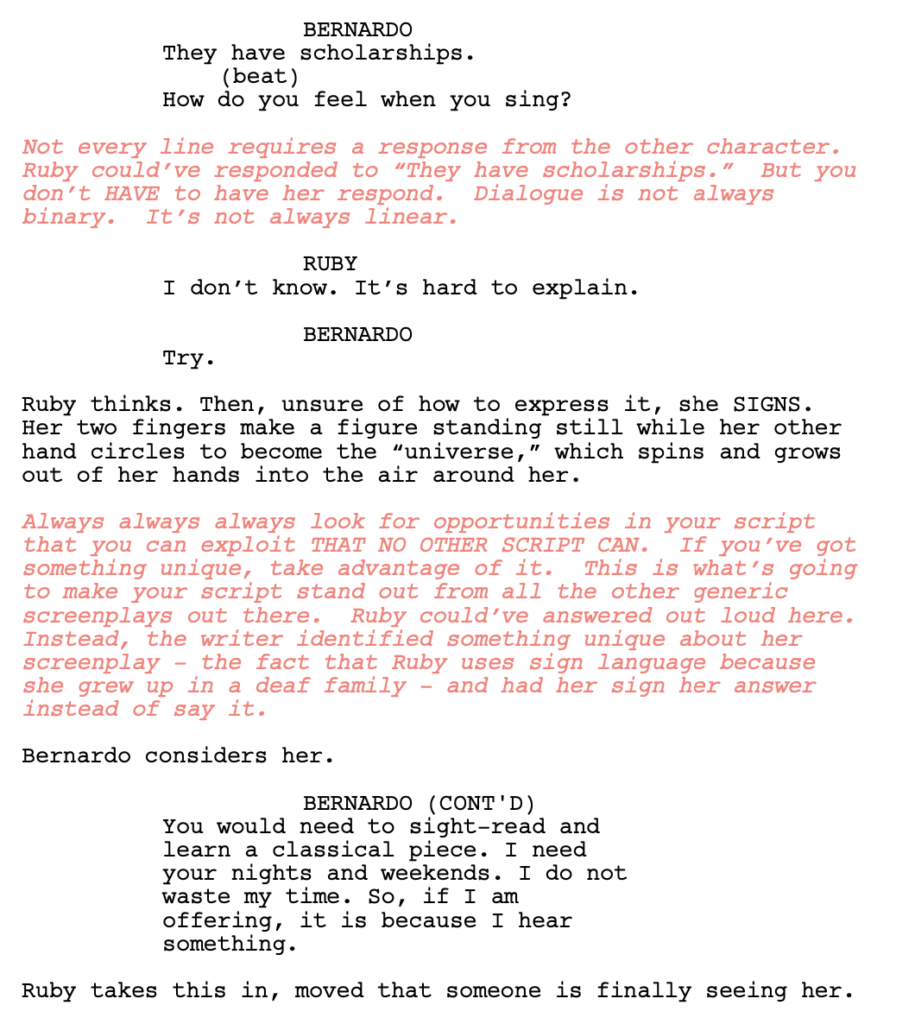

I loved Sian Heder’s, Coda, and thought it was the perfect time to bring back the “scene breakdown” feature I did with “I Care A Lot.” I’m going to highlight two scenes from the award-winning script (which you can download here), and while the focus will be on dialogue, I’ll spotlight a few other screenplay tips as well.

If you haven’t seen Coda, it follows a senior in high school, Ruby, the only hearing member of an, otherwise, deaf family. While you’d think this would make her sympathetic to her parents and brother, it’s the opposite. She’s always been looked at as “the weird girl with the deaf family” and, as a result, felt ostracized.

For the first time ever, Ruby is doing something for herself. She’s always wanted to sing but hasn’t had the confidence to do so. So she’s joined the choir class in high school and the teacher has assigned her to a duet with Miles, a boy she has a crush on. The following scene takes place in their music teacher’s classroom. They were supposed to practice their song together but didn’t.

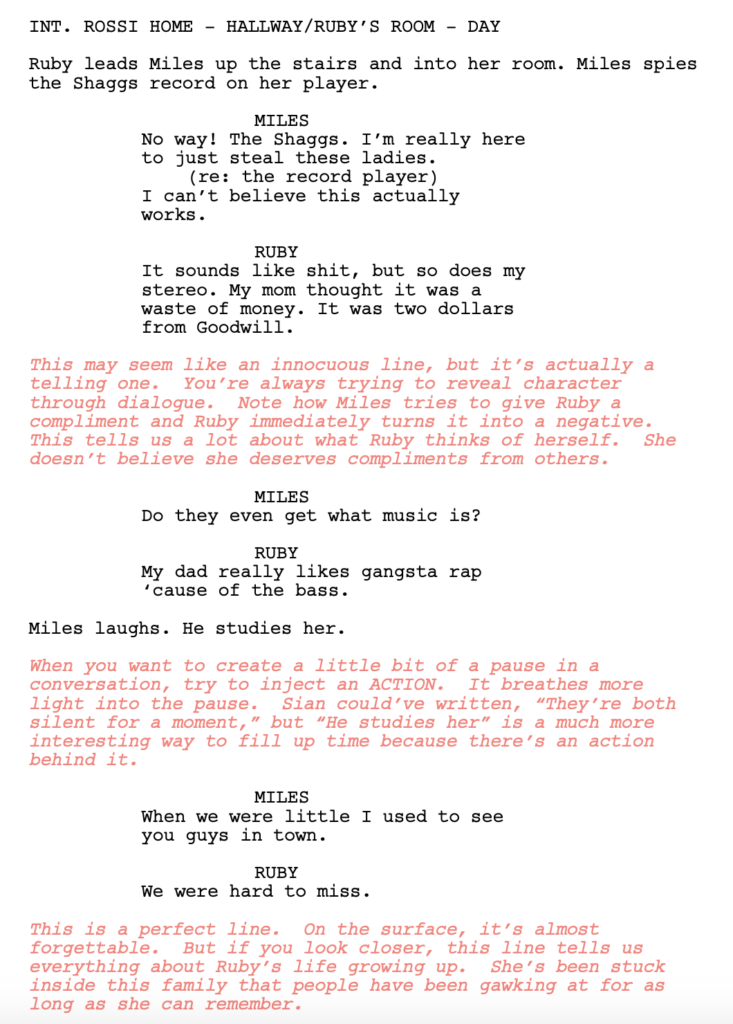

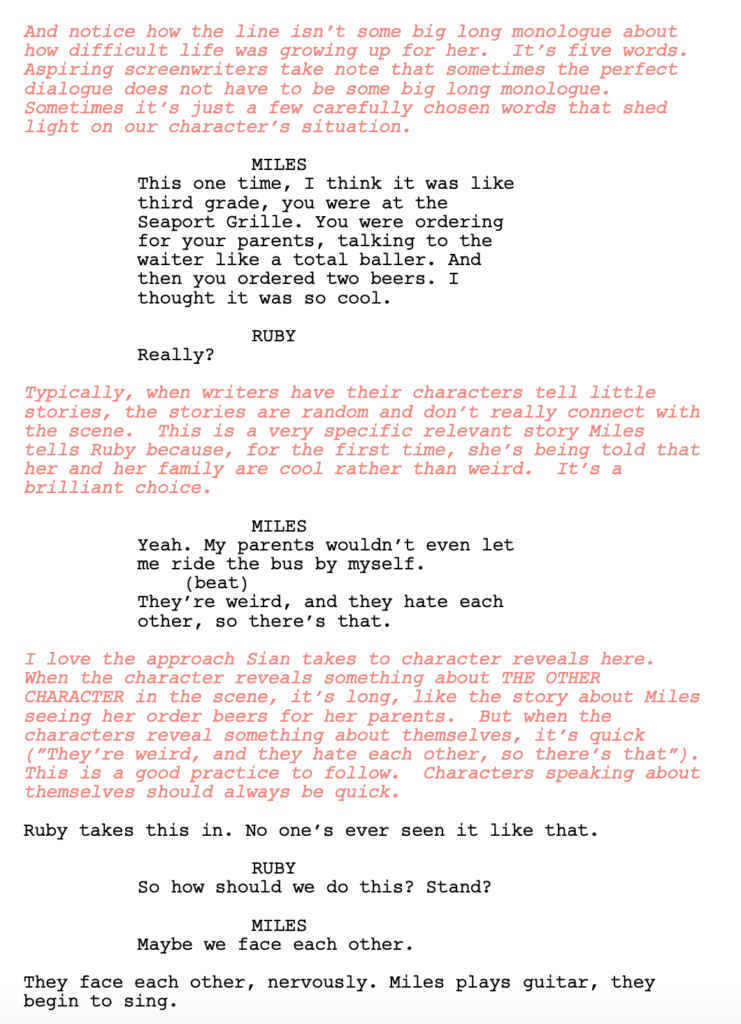

This next scene takes place 10-15 minutes later in the movie. This is the first time Ruby and Miles are practicing together and they’re doing so at Ruby’s house. Ruby is incredibly nervous about this not just because she has a crush on Miles, but because her family is such a wild card. She’s terrified that this may be a dealbreaker. I can’t stress this enough: Put your characters in situations they’re uncomfortable in. And with that established, let’s take a look at the scene…

And that’s it. I strongly recommend you read this script (it’s only 80 pages) AND watch the movie. Share your thoughts in the comments section, especially any additional lessons you picked up from the dialogue.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: During the summer of 1998, five camp counselors accidentally kill a stranger in the woods.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. This is co-written by Leigh Cesiro and Erica Matlin. Erica has been an assistant to Anthony Bregman, a producer on a number movies, including Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Writers: Leigh Cesiro & Erica Matlin

Details: 101 pages

Johnny Sequoyah for Sam?

I like killing people.

I’m speaking within the context of movies, of course.

More specifically, when a group of people kills a person, then have to cover it up and hope nobody finds out. As I’ve stated before, one of the most powerful things you can do with a character is give them a secret. A secret forces your character to lie. A lie means that every dialogue scene that character is involved in is going to be a dance – a dance to avoid suspicion, a dance to keep the secret intact. It’s built-in dramatic irony, which we all know is one of the most effective tools in screenwriting.

The year is 1998 and we’re at Camp Brower, a second rate summer camp. We meet best friends and camp counselors, effortlessly cool Jayne, self-assured Sam, sassy Alexis, and rule-following Benji, as they send a couple of sheep into a boys’ dorm to embarrass a sexist male counselor who’s teaching his young campers how to score chicks.

Afterwards, Team Sheep get together to figure out what they’re going to do for the rest of camp and get wind of a big party at the neighboring (and much ritzier) Camp Kensington. Everyone’s a little nervous cause Camp Kensignton is a lot cooler. But off they go that night and have a great time.

On the way back, though, the crew is messing around with a bow and arrow they find, drunkenly shooting arrows into the night, only to come upon a dead camp worker named Rat Tail, who’s got an arrow straight through his heart. When they realize they’ve killed him and that their lives are over if anyone finds out, they bury him in a shallow grave and agree to never talk about it again.

The next day they try and go back to normal but of course they’re all feeling guilty, especially Sam and Benji, who try to convince the others to tell the cops. Maybe the punishment won’t be so bad if they admit to it now. That idea gets shot down. Meanwhile, we find out that it was actually one of the other grounds people who killed Rat Tail. But our counselor group never finds this out.

They ultimately decide that a shallow grave won’t do the job and commit to moving the body. So they dig the body back up, put it in a bag, and try to lug it to a more secure location. Unfortunately, all the campers are running around, making it difficult. Will they be able to ditch the body of the man they think they killed but didn’t without anyone finding out? You’ll have to read Cruel Summer for the answer!

Because I’ve been so hard on the 2021 Black List, I’m going to try and take a more productive approach to today’s conversation. Cruel Summer, which is part Caddyshack, part Wet Hot American Summer, and part The Hangover, frustrated me. I’m all for a goofy comedy with a group of funny characters dealing with a difficult situation. But these scripts don’t work unless there’s at least one character who has some actual depth to them.

A lot of comedy writers screw this up. They just try and be funny. Which is good. You should be focusing on the funnies in a comedy. But we still need to connect with somebody in the story so that we care enough to keep reading. Because remember, we all have friends we can laugh with. In the majority of cases, we laugh a lot harder with them than we ever do at a movie. So a movie has to give us something else, and that something is someone to connect with and root for.

Check out Bridesmaids. Annie was a very well constructed character. In that first scene with the guy she slept with, we see her slip out of the bed in the morning, go into the bathroom, make herself look good, then sneak back into bed and, when he wakes up, she pretends she’s waking up as well, so he’ll think she always looks this good in the morning.

That scene showed us how desperate she was to find someone, to get married. This is what made the core plotline of her best friend getting married so clever, because we’d already seen that this is what she wants more than anything. The only thing she’s left with is her best friend’s friendship. So when that’s taken away too, we understand why she falls apart.

And it didn’t stop there. There was this whole backstory about her failed bakery. There was this self-sabotaging part of her where, when she finally finds the perfect guy, she screws it up, because she’s never had a guy who actually cared about her.

All of this was really well-constructed character development.

Meanwhile, I can’t tell you a thing about any of these girls lives in this screenplay other than that they like to goof around with each other. When readers complain about scripts being too thin, this is what they’re talking about. There was no effort to create any sort of depth to any of the characters, outside of a barely-explored battle for the open Assistant Director job between Jayne and Sam.

Bridesmaids was written over the course of six years. It takes time to get that depth and to get it right. This script may get there some day, but right now, it’s achingly thin. And if you sense the frustration in my voice, it’s because I’m frustrated.

When a reader sits down to read, the one thing they don’t want to question is whether the writer put their blood, sweat, and tears into the script. I have read some scripts I’ve disliked but still gave the writer credit because I could tell that they put everything into that script. The second I feel like that isn’t the case, I get upset. Because why should I invest if you haven’t?

“Mercury” set the bar for this Black List because you could tell that the writer left it all out on the field. There was no moment in that script where I felt they took a shortcut.

Now I understand that comedy is different from other genres because comedy has a naturally loose feel to it. It’s never going to be The Godfather. But the way I can spot a good comedy screenwriter is that they prioritize their main character. They make sure there’s a fully fleshed out human being at the center of the story who has flaws, who has inner demons, who’s imperfect, who needs something from this story to become whole.

And contrary to what you might think, that being obsessive about constructing your main character is going to make them too serious and unfunny, it actually makes the character funnier. That’s why Annie was so funny. Her jealousy was so well-established that every interaction that challenged it was a struggle for her. Her desperation to keep her best friend in her life was what led to the best scenes in the movie, like the toast-off.

If you don’t figure out what your main character is specifically going through, how can you create specific situations that she would be funny in? If I know my hero’s flaw is that she’s a chronic introvert, then you better believe I’m going to create a bunch of scenes where she has to be around a ton of people. And that her interacting with those people is going to matter to the story. That stakes are going to be attached to those moments. That’s what we’ll end up laughing at, her struggle to overcome that weakness.

Unfortunately, this is another example of a comedy that doesn’t have enough going on underneath the surface to create any real laughs, or any real investment. The plotting gets a little more intricate in the second act, resulting in a script that got better as it went on. But because I didn’t have anyone to latch onto, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m going to go back on what I said a little bit. It is possible to write funny screenplays without character flaws or character depth. We saw it with Borat. Hell, Airplane is one of the funniest movies ever and it doesn’t have a lick of character depth. It’s just HARDER. It’s harder to write these movies because you have to compensate for the lack of character depth by not just making your script kinda funny, but historically funny. Borat and Airplane are GIANT exceptions to the rule. You can try to be the next exception. But I guarantee you we’ll laugh harder if we feel like we know the hero and the real life issues they’re dealing with.

THE NEWSLETTER IS OFFICIALLY IN YOUR INBOXES! CHECK YOUR PROMOTIONS FOLDERS IF YOU DIDN’T GET IT!

Genre: Heist/Sci-Fi

Premise: Still reeling in the wake of her husband’s death, master thief Viola Crier signs on to a risky, last-minute job set to take place inside a man-made time loop, but as the number of loops increases, the job begins to spiral out of control.

About: Today’s writer and her script finished with 10 votes on the Black List. She is repped by William Morris Endeavor. This is her first screenplay. Or at least the first that’s made any noise.

Writer: Lindsay Michael

Details: 120 pages

How in the world do we follow yesterday?

I’m still thinking about it. Every time I think about what happened, I still can’t believe it. This guy hit someone on stage and then 15 minutes later, everyone gave him a standing ovation. We have to be living in a simulation for that to have happened, right? It defies all logic. There have to be some repercussions. Or are we going to all pretend it never happened, like the Oscar audience?

Anyway, we shall try to move on. And what better way to move on than with a new loop script! I’ve developed one of these myself so I know how tricky they can be. Let’s see how today’s writer handled it.

It’s 2038. A young female thief, Viola, is doing a job in Shanghai with her thief-husband, but he’s killed by the people they steal from. Viola is barely able to get out of Shanghai, with the help of a mysterious man named Okafor. Okafor tells Viola that he wants to hire her for the hardest job she’s ever done – stealing a 53 million dollar diamond. Go put a team together, he says.

She first gets 50 year-old Sybill, who is a master of disguise. She then flies to another country to pick up 19 year old safecracker, Cass. She then grabs explosives expert, Nemo, in Uzbekistan. And finally she gets pilot, Jackie, who’s going to fly everyone out once they steal the diamond.

The target is a place called Sandpiper Resort, in the Namib Desert. The place is a sand ski resort for the rich and famous. Okafor’s brother, a war profiteer named Wangari, took the diamond their dead father left for Okafor and Okafor wants it back. Wangari is in town to vacation at Sandpiper and Okafor knows he’s brought the diamond with him.

Once everyone is together, Okafor reveals their ace in the hole – he’s got a time-looping device. That means they’ll have not one, not two, not three, but four full shots to get the diamond. Anything after that and the time distortion field will destabilize. Nobody is very happy about this unpredictable device but since each individual’s take is 10 million bucks, they get over it fast.

The first run-through, the bomb they use to break into Wangari’s room ends up accidentally blowing a hole in the underground resort and sending a stream of suffocating sand in to snuff everybody out. Once the loop resets, they decide to spend the next shot on a test run. There are too many unknown variables that they need to figure out to pull this off. That leaves them with only two tries left. As you can imagine, the pressure mounts quickly, and the group come to the realization that four tries at the heist of the century might not be enough.

With scripts like this, you have to watch out for information overload and subsequent reader disorientation. Screenwriters are notorious for forgetting just how much information they’re throwing at the reader. To them, this information is common knowledge, so they assume it’s common knowledge to you, as well. This is what gets them into trouble. They’re operating on the assumption that you’re on the same page they are, when, in reality, you’re still ten pages behind them, trying to figure out that thing that happened on page 9.

Sandpiper starts out with a woman standing over a dead body in a morgue, a man whose wedding ring is featured prominently and, therefore, may have been our hero’s husband. Our hero then runs off with a Chinese detective, escaping a team of policemen, only to later get double-crossed by the detective.

At this point, I don’t know who my hero is, why we’re in China, what just happened to her maybe-husband, why she’s playing secret games with a Chinese cop, and what her job is. The next thing you know we’re meeting some random guy named Okafor who helps us escape on a train, then offers us a job to steal a diamond, then minutes later we go on a 4 continent montage to collect a mission impossible team, meeting four team-members who are going to help Viola do the heist.

It’s only after all this is over that we learn her and her husband were a thief-team and they’d been caught, which is why he was killed. In other words, I’m only learning what happened on page 1, on page 40. That’s not acceptable. I know, as writers, we think we’re cleverly withholding information and creating suspense by drip-feeding relevant backstory twenty pages at a time, but you have to be realistic. I’m supposed to keep track of those details while memorizing 4 different people on 4 different continents. That’s unrealistic.

This particular mistake is almost always a beginner one as it takes a while, as a screenwriter, to understand what a reader can and can’t keep up with. That comes through feedback from dozens of people reading your scripts. Which is one of the reasons I encourage new writers to first master simple one-character stories before moving on to Marvel-level 22-parallel storyline screenplays.

This issue continues throughout the script, making relatively straightforward plot points difficult to keep up with. For example, Viola gives up her 10 million dollar share to Jackie. Jackie says why would you do that. Viola says why does it matter? Then, 30 pages later, Viola reveals that Okafor promised her that, if she could steal this diamond for him, he’d use his time loop machine to send her back to save her husband.

Why all the cloak and dagger? Why not just tell us FROM THE BEGINNING that Okafor offers Viola this? I would’ve been way more invested in Viola’s pursuit since I’d know that the stakes were much higher. I just didn’t understand why everything needed to be a secret from the reader. Sure, sometimes you want secrets but not with basic important story elements, like motivation.

I’m not going to knock everything about the script. The loop heist idea is cool. And, strategically speaking, this is the kind of script you want to write if you’re trying to get those Mission Impossible studio jobs. You write in a “big action script” adjacent genre, like sci-fi action. But the hard stuff should be the characters and plotting in a screenplay, not conveying basic stuff like GSU. It just killed any potential enjoyment of the script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned : Never make a script exactly 120 pages. It makes seasoned readers think that you read a screenwriting book that a script couldn’t be over 120 pages and so you nipped and tucked your script relentlessly until you finally got it down to exactly that number. There are definitely things in your script that are not precious enough for you to hold onto that number. If you’re at 120, try to get it down 115. Even 117 is better than 120. 120 has “newbie” written all over it as it reeks of OCD adherence to ancient screenwriting requirements.

The newsletter will be hitting your Inboxes sometime today (Monday). If you are not on the newsletter list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll make sure you get it. I will, of course, be talking about the slap heard round the world and what it means for Hollywood going forward. I’ll be talking about the best picture winners as well as the best writing winners. I finally got to sit down and explore my thoughts on the Kenobi trailer. And there will be an opportunity to get a discount on your next set of screenplay notes. In the meantime, feel free to share your thoughts about that wild Oscars!