Today we learn the value of writing scenes that KEEP THE READER TURNING THE PAGES

Day 1: Writing a Teaser

Day 2: Introducing Your Hero

Day 3: Setting up Your Hero’s Life

This one is going to hurt.

I want you to take everything you’ve written so far AND THROW IT AWAY.

Okay, okay, okay. I’m kidding.

Sort of.

But mentally, I do need you to cross that bridge, because today’s post is about taking the mundane logical stuff that you’ve written and turning it into something fun and compelling. So far, you’ve been writing for yourself. Now, I want you to write for the reader.

A huge problem with first acts is that there’s so much to set up. You have to set up your four most important characters. You have to set up secondary characters. You have to set up your hero’s life. You have to set up the world your hero exists in. You have to set up the plot. You have to introduce some backstory. You sometimes have to set up rules (like in Source Code, the rules of the loop).

As a result, what a lot of writers do, without realizing it, is they write a first act that sets up all of these things then pat themselves on the back for doing so. Which they should. Setting up a bunch of stuff is hard. But if ALL YOU’RE DOING is setting things up, you’re not entertaining the reader, which means they never made it past page 10.

That’s what today’s post is about. It’s about writing entertaining scenes so that the reader wants to keep reading. What constitutes “entertaining?” Simple. Anything that makes the reader want to turn the page.

You can go about this in a couple of ways. You can write the boring version of all your first act scenes, focusing exclusively on setting everything up, then come back and rewrite each scene with a focus on entertainment. Or you can do both right away. Ask yourself what you need to set up in the scene then ask, how can I do that in the most entertaining way possible?

Luckily, we have a prototype film that does this exceptionally. The Matrix. Go watch The Matrix now. It’s free on HBO Max, if you have it. Pay attention to just how entertaining the first act is. Afterwards, you can come back here and look at how each scene not only sets things up, but keeps us entertained along the way.

SCENE NUMBER 1 – TEASER

A teaser will be the easiest scene to make entertaining because that’s the function of the teaser. If your teaser isn’t one of the most entertaining scenes in the movie, I suggest you delete it. In The Matrix, we get Trinity being approached by a group of cops and mysterious men in suits. There’s mystery all over, which makes this a good time to remind you that when it comes to entertaining a reader, mystery is a great tool. Who are these men? Who is this girl who can run on walls and do death-defying stunts? Wait, did she just disappear in that phone booth? What’s going on? A reader isn’t just hooked after this teaser. They’re obsessed.

SCENE NUMBER 2 – WE MEET NEO

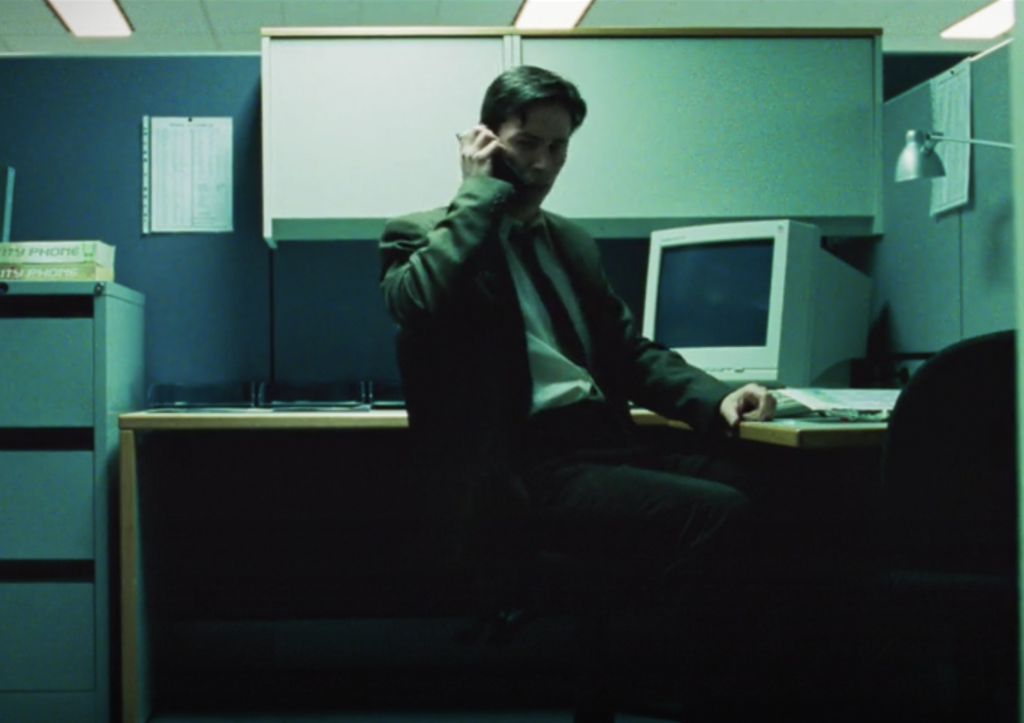

This is a scene a lot of writers would’ve tripped up on. You’ve had this giant teaser. You have to introduce your hero in a potentially ‘boring’ scene, since he’s home, by himself. This is, unfortunately, necessary, since we have to establish Neo as a loner, someone detached from the world. But the Wachowskis still keep the scene fun. Neo gets a mysterious message on his computer telling him to “follow the white rabbit.” When a group of partiers come to grab a hack Neo wrote, they ask him to come to the club with them and he says yes. Notice also that since there isn’t a lot the writers could’ve done in this scene (Neo alone in his room), they know to keep it short. If your scene isn’t as entertaining as it can be, shorten it up.

SCENE NUMBER 3 – NEO MEETS TRINITY

Another potentially boring scene. Two characters have to talk to each other. It’s very easy to make talking scenes boring. But here, the mysterious Trinity approaches Neo at the club. She plants some thoughts in his head, such as looking for something bigger. The Matrix. She can help him find it. It’s a short scene that keeps the mystery going. Again, the goal here is to get the reader to turn pages. That’s all we care about. And we want to turn the pages after Trinity, the badass we saw in the teaser, offers an opportunity to Neo to learn about the matrix. The matrix is, in essence, a mystery box. As long as it remains unopened, the reader will desperately want to learn more about it.

SCENE NUMBER 4 – NEO IS LATE

You will not have remembered this scene from The Matrix. But it’s a clever scene from a writing perspective. Let me tell you why. I read this type of scene a lot. It’s the scene where our hero, an office worker, has to talk to his boss about something, usually to set up all the work he has to do. In The Matrix, they use it as an opportunity to push the movie’s theme. The boss explains to Neo that everyone here is part of the whole. Individuality doesn’t work. Here’s the clever part, though, which helps turn a talky scene into something entertaining: Neo is late. So he’s getting scolded by the boss. This changes the tenor of the scene from “I’m setting up my hero’s workplace” to “A dramatically tense scene where my protagonist is being chastised.” It’s a small thing. But this is exactly what you should be doing. You shouldn’t just put two characters in a room to set up information. You have to find the dramatic angle that gives the scene an edge.

SCENE NUMBER 5 – NEO GETS A DELIVERY

This is ANOTHER scene that could’ve gotten boring quickly. It’s the first time we’re seeing Neo at his workplace. Writers could’ve gotten too wrapped up in what Neo was working on or who Neo worked with. The Wachowskis don’t bother with any of that. They have a FedEx guy deliver a confused Neo a package. Neo opens it. It’s a phone. It rings. On the phone is some dude named Morpheus, who informs Neo he’s going to help him avoid the three scary suited guys we saw in the opening scene. This begins a game of cat and mouse around the office that Neo eventually fails. Chase scenes or scenes where your character will have to hide: these situations have entertainment value baked in.

SCENE NUMBER 6 – THE INTERROGATION

The agents have now captured Neo and bring him back to the station, where they have some questions. It’s an interrogation scene that has some tricks up its sleeve to keep things extra-entertaining (Agent Smith makes Neo’s mouth disappear then inserts some sort of device in his body). Half of coming up with entertaining scenes is finding scenarios that do the work for you. Interrogation scenes are always tense so you know the scene is going to be entertaining. But notice how the Wachowskis keep building on the mystery. These strange agents seem to have these powers. They want to track Neo for some reason. There’s no way we’re not turning the page after these reveals. We have to see what happens next. As a comparison, I want you to go to the sixth scene in your script. Read it. Does it make the case that you MUST KEEP READING? If not, you can do better.

SCENE NUMBER 7 – THE CAR RIDE

After waking up and going outside, Morpheus’s team pick Neo up. Before Neo knows it, there’s a woman with a gun pointed at him telling him to take off his shirt. I mean look at how quickly these scenes jump into the good stuff. There’s no mindless dialogue. No setting up boring information we need to know. Each scene seems specifically designed to entertain first, exposition second. Next they pin Neo down and extract the tracker the agents put inside of him.

SCENE NUMBER 8 – NEO MEETS MORPHEUS

This is the most exposition-centered scene in the script so far. But the Wachowskis have done such a good job setting up Morpheus that, as readers, we’re all-in with this scene. Remember, not every scene is going to be entertaining in the same way. A car chase is different from a mystery is different from an argument is different from a suspenseful scenario. Here, the work for making the scene entertaining has already been done. We’ve built up Morpheus and, therefore, are thrilled to meet him. On top of that, we’re still curious what Morpheus wants from Neo, and how this all comes back to the matrix. Still, the Wachowskis look for ways to add even more entertainment. So instead of Morpheus saying, “Follow me,” and walking through a door into the Matrix, he gives Neo a choice, the red pill or the blue pill. It’s always entertaining to watch your hero make difficult choices, so it’s a great scenario to add to your scene. — Of course, after this scene, Neo crosses over into the real world and his second act adventure begins.

I can honestly say that there isn’t a single moment in the first act of The Matrix where I wasn’t invested, where I didn’t want to turn the pages. That’s what you’re aiming for with your first act. Yes, get all the relevant setup in there. But then go to work on every single scene, asking yourself, “How do I make this scene as entertaining as possible?” Think of each scene as its own short movie and you’ll have a head start. Because every movie needs to be entertaining.

If you can internalize this, you will be writing first acts that are tens if not hundreds of times better than 85% of the writers out there. Once a screenwriter learns how valuable even an eighth of a page is when it comes to, potentially, losing the reader, they make it their mission that no reader will ever be bored reading their screenplays again. And their screenplays become so much better as a result.

It’s time for you to make that jump.

Next First Act Post: Wednesday, March 9

Pages to write until next post: 2

Pages you should have completed after today’s assignment: 13

Genre: Superhero/Noir/Crime

Premise: When the Riddler starts leaving riddles at all of his murders taunting the Batman, the batster will have to team up with Catwoman to find him before he enacts his final sinister plan on the city.

About: Predictions were all over the map on how The Batman would open. Most were saying it would come in at 100 million. Well director Matt Reeves and his posse laugh at such predictions because The Batman made 128 million dollars this weekend! Stick that in your bat bowl. Reeves’ co-Writer, Peter Craig, burst onto the scene with 2010’s, “The Town.” He’s currently writing Gladiator 2 for Ridley Scott.

Writers: Matt Reeves & Peter Craig (‘Batman’ created by Bill Finger and Bob Kane).

Details: 3 hour running time!

I’ve heard that this Batman is the best Batman film EVER. Yes, even better than The Dark Knight. Could it be? These people are aware, I presume, that Robert Pattinson is playing Batman, right? I kid, I kid. Who doesn’t love themselves a little R. Patty, warts and all.

This is what makes Hollywood so amazing. They spend upwards of 3 million dollars to create a bat suit that makes a scrawny Pattinson look beefy. They get a good DP and gaffer in there to make sure the light is always hitting the suit in just the right way to make Pattison look menacing. Add a moody high quality score and choose an editor who knows how to edit around lousy takes and weird mannerisms. You do all that and now you have yourselves a convincing Batman.

But is it a good Batman? And has this Batman given us a good movie?

Okay, here’s today’s overly simplified summary of the movie. The Riddler kills the Mayor of Gotham. He also leaves a message for “Batman” that states the Mayor was dirty and so were a bunch of other Gotham politicians. We get the impression The Riddler isn’t done yet.

Police Lieutenant James Gordon has no choice but to bring the Batman in to comb over the crime scene. Afterwards, Batman looks over the riddle the Riddler left, which asks what do lying men do after they die. Batman answers “Lie Still,” in under a second, which gives him and Gordon a good chance of being on the next episode of Jeopardy.

After pestering the Penguin, who’s a club owner here, to tell him what he knows, Batman meets Selina Kyle, aka Catwoman, and the two decide to team up. As the crime scenes and riddles stack up, Batman desperately tries to catch up to the Riddler. And just when he’s getting close, the Riddler comes to him, surrendering. Except it’s a ploy. Because what the Riddler is about to do next will determine whether he takes over the entire city.

The thing that comic book movies figured out is that they can keep these films alive by hijacking sub-genres and using them to build a mould around the superhero-y stuff. One of the reasons comic book movies started to get so bad in the 2000s was that they kept going the origin story route. Audiences had gotten so familiar with that structure, unfortunately, that every movie now felt familiar.

So superhero films started experimenting, even though they didn’t really know what they were doing. This gave us movies like Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns from 2006. It wasn’t an origin story but it kind of was. The film just never found its footing. Enter the sub-genre, a strategy that Marvel began implementing. You’ve got the Buddy Cop movie (Captain Marvel). You’ve got the Spy movie (Winter Soldier). You’ve got the John Hughes High School Comedy (Spider-Man: Homecoming ). This gave comic book movies a new life because now, you weren’t really going to see a comic book movie. You were going to see a high school comedy… with superheroes.

The Batman continues this strategy, as it embraces “Film Noir” as its sub-genre. You’ve got a deep baritone Bruce Wayne, narrating the state of the city in the film’s opening scene. Every scene is painted in thick endless shadows. Characters don’t speak so much as pose and try to make the dialogue sound cool. And, most importantly, it all works. The Batman as a noir film is great.

But the screenplay… the screenplay is another story.

Sticking with this month’s theme, I was hyper-focused on the first act. And it pretty much followed the same blueprint I’ve laid out for all of you. We get our teaser, which is that the mayor is killed by The Riddler. Then we introduce our hero, The Batman, along with a couple of other characters. We establish the world (Gotham) they’re in, specifically the fact that crime is a big problem in the city, which is why Batman has gotten involved.

Batman’s intro, where he arrives to take down a group of bullies about to beat a subway rider into submission, quickly establishes that he’s a badass and takes his job of protecting the city seriously. We need to have a good feel for your hero after their first scene. The Batman succeeds in that regard.

The inciting incident is technically the mayor’s murder, which already happened in the teaser. But it doesn’t officially become the inciting incident until Batman is called to the murder with Gordon, and they inspect the crime scene. It is here where The Riddler’s game is introduced, adding a secondary element. Batman will have to solve the murder. But also solve Riddler’s larger puzzle.

Reeves’ decision to go this route was a wise one. When you have a universe as wide and varied as Gotham, which is home to a lot of characters, you risk the reader getting lost in all the noise. So you want a narrative that’s immediately understandable, something to counterbalance the huge complex world you’ll be tasked with bringing to life.

Utilizing one of the oldest story setups in the book – the murder investigation – is a great way to keep the story focused and, as a result, keep the reader clued in. While there were a few places in the movie where I had to think hard to remember what was going on, I was never confused, like I am with some of these movies that have 800 characters. This is because I always understood the core of Batman’s goal: Find the Riddler.

The problem with The Batman is that it thinks too highly itself and, therefore, doesn’t realize that its investigation is kinda bland. The rhythm of the story is too predictable. Go chase one clue, find a dead person with a riddle card attached to them, someone reads the riddle, Batman always answers the riddle within two seconds, this sends them to their next destination, where they find another dead person and another riddle. Which sends them to their next destination. And so on and so forth.

This would all be well and good if the characters were great. But the two most interesting characters, the Penguin and the Riddler, are given limited screen time, while their heroic counterparts, Batman and Catwoman, are given the majority of the time. And while our heroes are pretty cool, they’re not captivating enough for us to truly care about what’s going on.

This partly has to do with the noir genre itself as it often feels like characters aren’t talking to each other, so much as directly to the audience, delivering their lines as stylistically as possible. There’s a detached quality to the dialogue and the line-readings that speaks to the bigger problem with noir – which is that it always looks cool, but, emotionally, feels cold.

Which is a strange thing to say because everything else about the movie – the way it’s filmed, the way it’s lit, the way it’s designed – implies that it’s a much deeper comic book movie than you usually see. But it isn’t. It’s a cinematography class. It’s got costume design up the wazoo. But everything else in the film is skin deep.

Nobody’s going through any internal battles outside of some vague references to Bruce’s difficult childhood. Contrast this with Arthur Fleck in Joker, who’s so very desperate to connect with others. Who’s tasked with taking care of his aging mother. Who must battle a strange disorder daily (his spontaneous laughing). Who must fight off an inner rage. We really feel like Arthur is a person struggling through life. Batman, meanwhile, is just a guy who seems upset that there are a lot of criminals around.

This makes the three hour running time seem ridiculous. You can have that extra hour if you’re going to use it. But if all you’re going to do with that hour is turn 2 minute scenes into 4 minute scenes, and 5 minute scenes into 10 minute scenes, you’re killing your narrative’s momentum. There was this scene about two hours in where Bruce is talking to Alfred in the hospital and I swear it was 15 uninterrupted minutes of them droning on to each other.

I know we say for every Marvel movie, “That could’ve been shorter,” but in this case, it’s true. This movie could’ve lost an hour and it wouldn’t have affected the film AT ALL.

I do think it’s cool that Matt Reeves made this badass looking superhero flick peppering in a 90s edge that included “Seven” references and a Nirvana-inspired Bruce Wayne. But halfway through this movie, when I realized the investigation narrative was going to keep hitting the same beats over and over, I mentally checked out, watching the rest of the film with only a passing interest.

There’s good here. Just not enough of it.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The Reluctant Team-Up always works. This is when your hero reluctantly teams up with another character, as is the case here with Batman and Catwoman.

Genre: Action/Fantasy

Premise: A combat veteran fights to keep his inexperienced squad alive in the remote Scottish Highlands as they’re hunted by descendants of a Celtic Demigod.

Why You Should Read: I’ll let the logline speak for itself, either it’s your bag or not ;)…. Comparisons: Dog Soldiers/Wickerman/Southern Comfort.

Writer: B. Jack Azadi

Details: 97 pages

I LOVE this setup. I love anything where a group of tough dudes try to take down a supernatural something-or-other. It’s why I loved Aliens. It’s why I loved Predator. It’s why I liked Pitch Black. There’s something about that moment where they realize they’re vastly overmatched that gets me every time.

Surprisingly, these movies have fallen out of favor the last couple of decades. I’m not sure why but I suspect it’s because there were a bunch of Aliens clones that kept coming out summer after summer that were horrible. That and the fact that teams in camouflage have been replaced by teams in capes. The movie that probably sunk them for good was 1998’s Deep Rising. God was that movie bad. But I still think this is a winning formula when done well. Which is why I’m excited to read The Last Scion.

Let’s take a look!

A Scottish military unit has gone missing. So it’s up to a new unit, led by Lieutenant Greystone, to head up into the Scottish Highlands to find out what happened to them. Greystone will be accompanied by combat vet Sergeant Jackson, mysterious intelligence official Lieutenant Parker (the lone female on the team), a tough dude named Paddy, and roughly ten more men.

The team heads up to where the missing unit was last spotted and they find their first clue – a dead soldier’s body whose face has been eaten off. At this point, they’re operating on the thesis that some sort of animal attacked the team. And when they see some overgrown wolves scurrying about, they figure they’ve got their “man.”

But then, when everyone is hanging out at camp, a freaking axe comes flying out of nowhere and lodges itself in Greystone’s face. The soldiers go nuts, busting out their guns and firing in every direction. After everyone settles down, they construct a new plan: GO BACK DOWN THE MOUNTAIN AS FAR AWAY FROM THIS PLACE AS POSSIBLE.

Except it’s not going to be that easy. After a nice old lady kills one of their soldiers, the crew asks Parker what she knows. She confesses that they might be up against Celtic warriors who have kept living up here for centuries and they may even be stronger than average men. No sooner than that analysis is dropped, Parker, Paddy, and Jackson are kidnapped and brought to the Celtic village. Once they realize they’re going to be slaughtered, their final plan is formed: ESCAPE AT ALL COSTS.

For obvious reasons, I was hyper-focused on the first act of The Last Scion, which makes some pretty large blunders that send ripples throughout the rest of the screenplay. Let’s take a look at these trouble spots.

The first issue is the teaser. The teaser takes place 10 years ago. We follow an injured female soldier in the Western Mountains of Scotland as she runs from something. We see her run, we see her run, we see her run. She falls. A wolf emerges, grabs her, drags her off-screen. END OF TEASER.

Now you might say, “What’s wrong with this teaser, Carson? You’ve got an injured woman. She’s running. Something’s chasing her. There’s a lot of excitement going on. Isn’t that what you want?”

No.

Well, yes. It’s great to have a life or death situation in a teaser. But if all you’re showing us is generic imagery (a woman running, a woman falling, something pulling her away), it doesn’t register at all. It feels like every other version of this scene ever. You have to find a way to make it different, like in “It Follows” where a woman is running away from seemingly nobody. Or you have to throw some reveal in there that turns the scene upside-down. Like in Halloween where, after we witness this brutal murder in POV, we reverse to see the mask taken off and it’s a ten year old boy.

A garden variety action sequence is no better than no action at all.

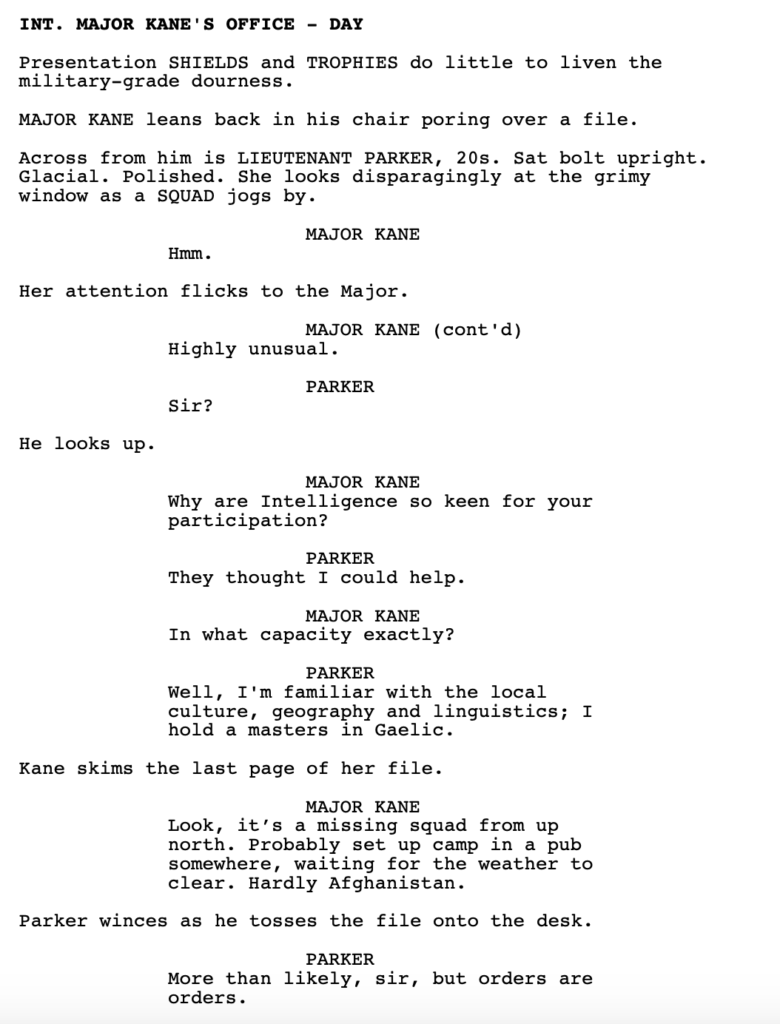

But the much bigger faux-pas of The Last Scion is the character introductions. The character introductions were so restrained and/or minimal that I didn’t even know who the hero was. I assumed it was Parker, since she was the outsider. Let’s check out her introductory scene:

Is this the opening of an exciting character you want to get to know better? All she does is sit in a chair and answer questions. That’s not how any major character in your script should be introduced. Introduce them with panache. Show us why they’re cool, unique, dangerous, exciting, interesting, mysterious, ANYTHING. Anything more than “Answers Questions Woman.”

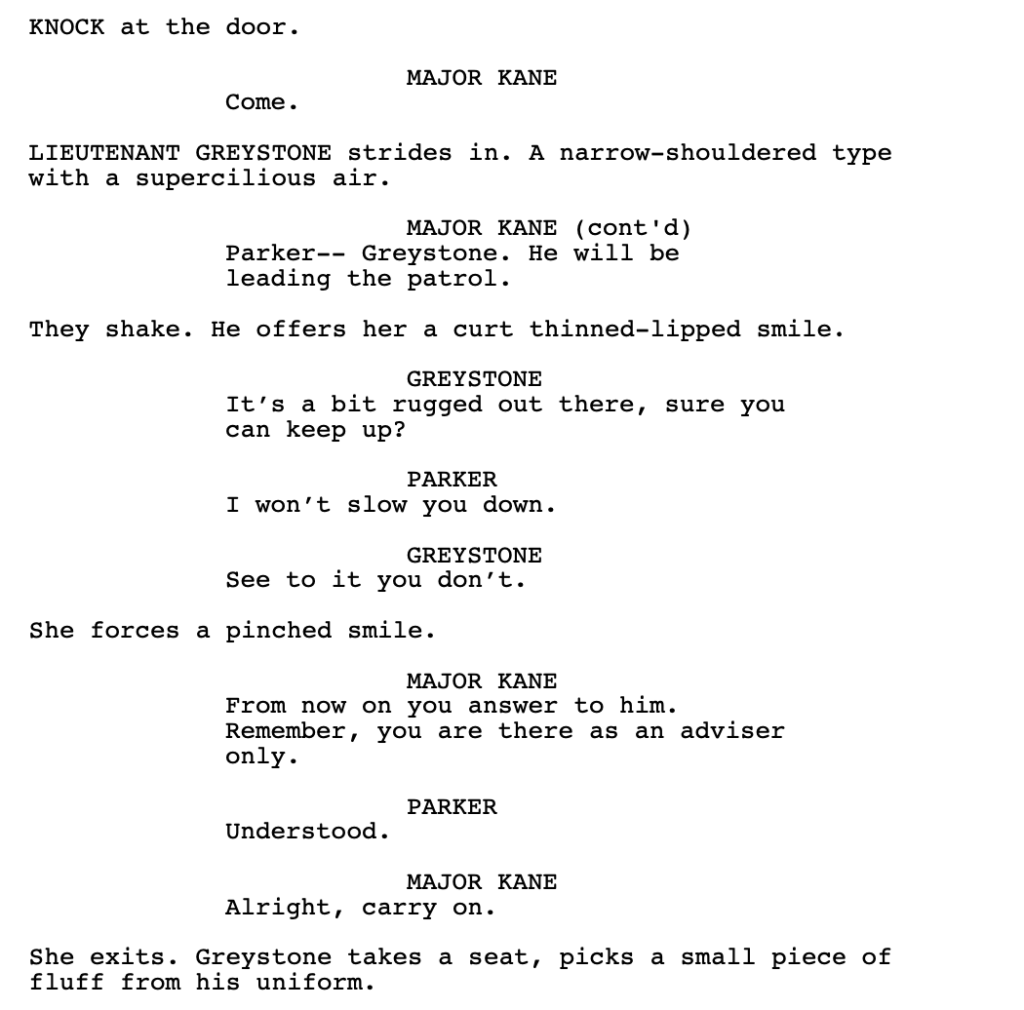

The final three characters who survive in the script are Parker, Paddy, and Jackson. Let’s check out how Paddy and Jackson are introduced…

The second introduction at least tells us a little bit about Jackson. But it’s not a strong introduction by any means. You have to look for visual and active ways to make a character stand out so the audience knows: THIS PERSON IS IMPORTANT. THIS PERSON IS COOL. Cause if they’re not cool, we’re not paying attention to them. And that was a big issue here. A dozen characters were introduced and I didn’t know who the main three I was supposed to be focused on were until page 80. That’s specifically because of the poor introductions.

This is a major lesson I need to get across to you guys. All this stuff I’m teaching you about the first act isn’t just about the first act. It’s about the whole script. Because if you’re not doing certain things right in the first act, it reverberates throughout the rest of the story.

In my latest newsletter, I talk about Richter scale moments, moments in the screenplay that shake the ground to such a degree that the reader can’t help but get excited to read on. I didn’t see enough of those here. For example, we build up Parker as this big mystery character, to the point where she barely speaks. We occasionally see her sneak away and send a text to someone. So we’re expecting a big reveal with her, a Richter scale worthy moment. But when they finally confront Parker about her secret texting, she comes clean, explaining that they’re up against possibly super-strong Celtic warriors – something we’d pretty much figured out on our own already.

When you have a reveal scene, it needs to actually reveal something. It can’t reveal 15% more than what we already know. Especially in a movie like this. The reveal needs to shake the very foundation we’re standing on.

My favorite part of The Last Scion is when they’re captured and taken back to the village because I not only felt like they were in serious danger, but this place was so weird and unpredictable that you got the sense anything could happen. There’s a moment where the Celtics nail a soldier to a cross, like Jesus, stab him to death, and then the Celtic children dance in the dying soldier’s blood as it sprays all over them.

Unpleasant image? Sure. But shocking? Yes. And this script needed a lot more of that.

If I were producing this script, the first thing I would do is sit down with Azadi and figure out who the hero was. Cause right now, it’s not clear. Then I would spend the next three hours brainstorming an introductory scene for that character that audiences would remember for the rest of their lives. That doesn’t mean he has to outrun boulders. You can make a big impact in a small setting. Go watch Anton Chigurh’s opening scene in No Country for Old Men to see how. But we need to make this guy badass and we need to make it clear he’s running the show. Cause I had no idea who was running the show for three-quarters of the script.

Honestly, that’s going to solve a lot of the script’s problems. From there, you need to create bigger Richter scale moments. The bar isn’t three feet off the ground. The bar is three miles in the sky. Don’t come with your ‘okay’ stuff. Come with the stuff that’s going to get people talking for years once they see your movie.

Cause premises like this are perfect for movies. So the potential is there. But this feels like it’s 4-5 drafts from reaching that potential.

Script Link: The Last Scion

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: With scripts like this that have a ton of characters introduced up front, you need to dedicate an entire week of your prep JUST ON COMING UP WITH CHARACTER NAMES. Make sure every name is distinctive, memorable, and represents the character in question. I remembered, maybe, one quarter of the soldiers here because there were simply too many of them.

Today we discuss setting up your hero’s life, which will have an enormous effect on how much we care about them during the movie.

Day 1: Writing a Teaser

Day 2: Introducing Your Hero

Now that we’ve discussed introducing your hero, we must discuss introducing their life.

There’s a specific reason for this. When you reach the second act, your hero is going to be entering the “adventure” world. For a movie like The Matrix that will mean a computer simulated kung-fu reality brimming with reckless gunslinging and killing. For a movie like Neighbors, it will mean a world of keg-stands and bongs, sexual experimentation and endless partying. In order for the uniqueness of these worlds to register, you must contrast them against the mundane ordinary world your hero starts in.

Setting up your hero’s world will consist of three primary things:

- Their job

- Their family

- Their social life (relationships and friends)

Job – A person’s job takes up half their life. So it’s a huge part of a character’s identity. You can convey so much about them by showing just one scene at work. For example, if your character is a lowly office worker at a giant company like Amazon, you can convey that they’re just a cog in the machine, a number, lonely and unimportant. Conversely, if they’re the CEO of that same company, you can show how everyone admires them, kisses up to them, courts their approval. They are so used to this praise that they have become arrogant, disassociated from reality.

By the way, “job,” is relative in that, if your character is 15 years old, their “job” is going to school. So you’d substitute showing them at their job with showing them at school. Then again, you could do both. Maybe they have a job bussing tables after school every day. What you’re trying to do with any character is build someone who’s interesting, who isn’t your Average Jane. A high school kid who’s forced to work a job after school is a lot more interesting than a high school kid with a cushy privileged life. So look for those opportunities whenever you create a character.

Family – We can look at family in two ways. Either as the wife/husband and kids. Or the parents and extended family. What you’re going to want to focus on here is the status of these relationships, as they will have a huge effect on how your hero approaches life. For example, if your hero is like Lester Burnham in American Beauty, he lives in a family where both his wife and daughter are embarrassed by him. Every night he walks into that house, he’s emasculated. This has turned him into a sad frustrated man in all aspects of his life.

Probably one of the most important relationships you’ll establish is that of your hero’s relationship with their parents. Since there’s a lifelong desire for children to seek their parents’ approval, all you need to do to create conflict is establish some resistance from a parent, and now you have that unresolved relationship that adds complexity to your hero. If you haven’t seen Peacemaker, a central theme in the show is Peacemaker’s Alt-Right father who’s always thought Peacemaker was worthless. So Peacemaker is constantly balancing his disdain for his father against his need for his approval.

And it doesn’t just have to be parents. You can create unresolved conflict with siblings as well. There was this silly Christmas romantic comedy on Netflix this past December called Love Hard about a guy who catfishes a girl, who then surprises him by showing up at his house for Christmas. In the movie, the main guy is a loser who still lives with his parents. Meanwhile, his brother shows up for Christmas and it turns out he’s married to the perfect girl. Has the perfect job. He’s annoyingly successful at everything he does. That contrast between the two brothers led to the best laughs in the movie.

Social life – Your hero’s social life will consist of who they’re dating (or not dating), their friends, and what they do for fun. Unlike family, a hero’s friends will be more of an extension of them rather than a source of conflict. That’s because your hero chooses his friends but does not choose his family. Of course, depending on how involved the friend is in the plot, their “conflict” status may change over the course of the movie. We saw this with Annie in Bridesmaids. She starts off as having the perfect friendship with Lillian. But then, as jealousy takes over, their friendship deteriorates.

If your hero has a girlfriend or boyfriend, there will almost always be some level of conflict in their relationship. One of the most common ones is, are we going to get married? One of the two is reluctant to take that step. Another one is, are we going to have kids? Or, depending on the movie, it could be simpler. It might be that one person in the relationship is too selfish. Or they’ve been offered a job in another city and they’re thinking of taking it, putting the relationship in jeopardy. Or maybe your hero isn’t involved in a relationship at all. Maybe they’re an incel, like The 40 Year Old Virgin. And their “setting up your hero’s world” scenes are more about them *trying* to get a girlfriend than having problems with a girlfriend.

The reason you’re showing us all these things isn’t just to create contrast between the ordinary (first act) and adventure (second act) worlds. You’re doing this so we get to know your hero. The more we know your hero, the closer to them we’ll feel and, therefore, the more we’ll root for them. I’ve seen writers skimp on setting up their hero’s life and there’s a noticeable dip in our interest. We just don’t care as much because we never felt like we knew the guy in the first place.

Now that you know what to do, let’s talk about application. Because while it would seem you just tackle these issues one by one, that, unfortunately, isn’t the case with screenwriting. You will often have to set MULTIPLE THINGS up in the same scene.

Let’s take a look at a recent Disney film, Jungle Cruise, as an example. In Jungle Cruise, we meet Lily (Emily Blunt) trying to steal a map from an old governmental building. The writers could’ve stopped there. They could’ve said, “This is our hero. We’re going to dedicate an entire scene to setting her, and only her, up.” But anybody can do that. One of the things Hollywood pays writers to do is combine scenes that do multiple things, and therefore move the story along quicker.

Therefore, they had this other character namedMacGregor, who’s Lily’s brother, lobbying a group of potential investors for an expedition, in the same building. During his lobbying, Lily sneaks off to find the map. But the writers didn’t stop there. At some point in the story, they needed to introduce the primary villain, Jochaim. They could’ve done this by giving Jochaim an isolated introduction. But instead, while Lily is sneaking through the building, she bumps into Jochaim, who is very suspicious of her behavior. And, boom, just like that, the writers have set up three of the primary characters in a single scene, established what Lily does for a living, and set up the plot (follow the map to the treasure).

An interesting thing about that scene is that it’s around ten minutes long, which means the writers decided to write one big scene to set up Lily as opposed to a bunch of smaller ones. I tend to like this approach because it allows the writer to create more of a “mini-movie” with the scene, with its own little beginning, middle, and end. But, ultimately, that decision is up to you, and will be dictated by the type of story you’re telling.

How many of these “setting up your hero’s world” scenes you’ll write depends on a) if you wrote a teaser or not and b) how long your scenes are. We can figure this out with some simple math. Your inciting incident is going to come somewhere between pages 12-15. Let’s say you didn’t write a teaser. That means you have 12 pages before the inciting incident. The average scene is 2 and a half pages long. Therefore, you will write about 5 scenes that set up your hero in their world. That may drop to three, maybe even two scenes, if you have a long teaser.

Let’s not forget that this is a creative endeavor and, therefore, you can attack your story however you want. But whichever direction you choose, try to set up your hero’s job, family, and social life if possible. The more we know about your hero, the more we’ll care about them, which has an enormous effect on how invested we’ll be during the adventure (the second act).

Next First Act Post: Tuesday, March 8

Pages to write until next post: 8

Today we discuss the most important scene you will write in your entire script.

Yesterday, we discussed the teaser scene and talked about whether you should include one in your script or not. Now that you’ve decided, we can move on to either the first scene of the script (if you didn’t include a teaser) or the second scene (if you did). This is going to be your main character’s introductory scene. It is not hyperbole to say this is the most important scene in your script.

The reason for that is the same reason I bring up in half the script reviews I do. Just like nobody in real life wants to hang out with an unlikable person, no audience wants to hang around an unlikable character. So the scene must make us like the hero on some level. I know this word “like” is heavily debated amongst the screenwriting community. The way I define it – insofar as what we’re trying to do – is that you must make us care about the main character enough that we want to root for him.

What’s tricky about this scene is that introducing your hero is only one piece of the puzzle. You also want to introduce their flaw. This is because there are two journeys going on in a screenplay. There’s the external journey, which entails all the physical things we see our hero do to achieve their goal. And there’s the internal journey, which is how your hero changes on the inside while all these external things are happening.

In order for a character to change, you will need to lay out what their starting point is. If they are a selfish person, and their inner journey will show them transform into a selfless person, then it’s imperative you let us know right off the bat that they’re selfish.

On top of establishing likability and a flaw, you will also need to make the scene where they’re being introduced entertaining. A critical mistake a lot of writers make is writing stillborn hero introductory scenes. It’s as if they believe that as long as they set up the character, they’ve done their job. No no no no no no. On top of everything else, the introductory scene itself needs to be entertaining.

This is going to be a theme throughout this month. You don’t get gold stars for setting up characters, setting up plot, or establishing backstory. You only get gold stars when you do all of that stuff IN ADDITION TO entertaining the reader.

So how does one do all of these things in a single scene? The most common way is to show your hero at their job encountering a relatively high-stakes problem. The reason you do this is because a problem necessitates choice and action. Your hero will have to make decisions, which will help us get to know him, and he will need to take action, which gives the scene life.

You see this in a lot of procedurals, cop movies, and serial killer flicks. We meet our hero detective as he arrives at the murder scene. The murder is the “problem.” We need to find out who did it. Or at least find a solid clue that will set us on the right path.

There are a lot of things you can in this scenario to achieve your goals. You can make our detective charming to everyone he encounters, which makes him likable. Or we can make him an underdog. He’s the low guy on the totem pole. Nobody wants him here (everybody likes an underdog so we’re immediately rooting for him). And, of course, he can outsmart the other, more seasoned, detectives, finding the clue that everyone else missed. Since audiences love smart protagonists who are great at their jobs, they immediately like this guy.

These scenes also tend to be entertaining because there’s a mystery component to them. When someone’s been murdered, audiences are curious to find out who did it. They like following someone around who’s trying to answer these questions.

The great thing about generating a problem your hero must solve is that it’s a setup that works for virtually any scenario. If your hero is an office worker, maybe they accidentally deleted their speech and have to give the big boardroom presentation from memory. If they’re a sniper, maybe they’ve been ordered to kill a madman but when they get the target in their sites, there are children in the way, which means they will have to kill the children before they kill the target. If they’re a high school teacher, maybe they’re told by the football coach that they have to reverse a failed test score so that the school’s star player can play in the championship game this weekend.

You’re just looking to put your hero in an unfavorable predicament and see how they respond. That’s the opening to everything from Raiders of the Lost Ark (must escape a crumbling cave) to Toy Story (new Christmas toys arrive to potentially replace the current ones) to The Invisible Man (must escape her evil husband’s home before he wakes up) to The Bourne Identity (a bullet-riddled man is rescued at sea but he has no idea who he is).

Introducing some sort of problem your hero has to face is one of the easiest ways to achieve all the things I talk about in this post.

In order to convey what we’re going for, I’ll highlight the best character introduction I’ve seen in the last five years. That would be the introduction of Arthur Fleck, aka The Joker, in the movie, “Joker.”

The reason I liked this intro so much is because the writer had one hell of an obstacle in front of him. He had to take a psychotic weird unpleasant man and somehow make us root for him. Or at least care about him for the next two hours. Therefore, he constructed this clever opening scene that has our hero getting attacked and humiliated. Remember that audiences will always like characters who are bullied, ganged up on, or taken advantage of. So after this scene, we’re Team Arthur all the way.

I’ve noticed some people online point to this scene as over-the-top and trying too hard to make us like Arthur. I vehemently disagree. This character was going to be so unpleasant for such an extended period of time that the writers had to go big with his introduction. They had to make us really really really care for him. This wasn’t some Adam Sandler movie. This was a disturbed character. We had to massively tip the ‘likability’ scales early on to get people on board.

For those who haven’t seen Joker, here’s the opening scene:

I don’t want to pretend like this is easy. Screenplays are weird in that, sometimes, a story works against what the writer wants to do. For example, maybe your hero is a bank robber. What better way to introduce them than robbing a bank? But what if our bank robber also has a wife and a kid who are going to be a major part of the story? And you start thinking, “I can make my hero a lot more likable if I introduce him around his wife and kid first. And the bank robbery will have higher stakes if we know the hero has a wife and kid waiting at home. So why don’t I set the three of them up in a scene at home first, then send him off to rob the bank.”

In other words, you sacrifice the more entertaining scene – the bank robbery – for a family set-up scene. Is that the right call? Maybe. Maybe not. Funny enough, this is exactly the dilemma Joker faced. In the original script, the opening scene was Arthur meeting with a social worker. The scene did a good job getting into Arthur’s head, making him sympathetic because he obviously has mental issues. But the scene wasn’t entertaining enough to open the movie on. Which is why director Todd Phillips opted to go with the sign-stealing scene instead. It was more entertaining AND it made Arthur sympathetic.

If you can do everything in one scene, you should do it. If not, here’s how I would prioritize the three requirements of an introductory scene.

- MAKE US LIKE HIM! – If we love your hero, we’ll be a lot less finicky about plot and story issues.

- MAKE THE SCENE ENTERTAINING – It’s still early enough in the screenplay that a reader is ready to give up on you. So don’t just introduce your hero. Make sure the scene itself is entertaining.

- INTRODUCE YOUR HERO’S FLAW – While I would prefer to know your hero’s flaw immediately, I don’t think it’s as important as making us like him and making the scene entertaining. If you must hold off on one of these three, you can push the introduction of the hero’s flaw back a scene or two.

Join me back here tomorrow when we talk about secondary characters as well as the scenes you’ll write before the inciting incident.

Next Post: Tomorrow (Thursday, March 3)

Pages to write until next post: 1.5