I got involved in a wild and rather impromptu Super Bowl party so I don’t have the time or mental bandwidth to put together a spectacular post but I do want to remind everyone that the “ANYTHING GOES” Amateur Showdown is happening next week. “Anything Goes” means you can submit any genre of script you want. Entries are due at carsonreevese@gmail.com by Thursday, February 24th, 10pm Pacific Time. Include your title, genre, logline, and why you think it deserves a shot to be featured on the showdown. And, of course, make sure you attach a PDF of your script should I choose to feature it!

Okay, now let’s get to what I really want to talk about, which is the “Nope” trailer, Jordan Peele’s new movie. Before I get into what I thought about the trailer, I want to make it clear that I’m trying to be objective about this. Because what happens with every breakout success such as Jordan, is that the story has to evolve. You can’t just keep praising a director for every movie they make. It’s happened with, maybe, five directors throughout time. For everyone else, the masses need a new storyline to stay interested.

So when I think about Jordan Peele, that’s what I think about. I wonder if he’s on the same path as M. Night. M. Night had a great first film (I’m talking about Sixth Sense, not his two tiny indie dramas), a much celebrated second film (Unbreakable) that, in retrospect, hinted at his weaknesses as a storyteller, and then a third film (Signs) that made everyone rethink if Night was the genius they all thought he was. From there, his movies spiraled out of control.

Here’s how I see Peele’s career so far. He wrote an amazing script in Get Out. It was so good. Those of you who’ve been on the site for a long time know I praised this script well before it became a breakout hit. Now, what’s important to know about the Get Out script is that Peele had been working on it forever. I think he said he’d been rewriting it for 10 years. Which is why that movie was so tight and strong.

Peele didn’t spend nearly as much time on Us and it showed. What started out as a cool idea – a home invasion movie where dopplegangers try to kill a family – became an outrageous sci-fi horror flick that involved hundreds of miles of underground tunnels where doppelgängers prepared to kill their above-ground clones. And let’s not forgot about all the bunny rabbits that were, for some reason, in the movie. Us was a cool movie. I thought the overall experience was fun. But, on the whole, it felt untethered, odd, and way too raw.

Next up came Candyman, a film that Peele produced instead of directed. I tried to warn everyone that the original Candyman movie made zero sense and that there was nothing an update was going to do to change that. I mean, the main villain is named the Candyman and yet the movie focuses on bees. When a story tells you it doesn’t make sense, trust it. So it wasn’t a surprise when that movie did poorly.

Now comes this trailer for “Nope” and it’s a conversation piece, I’ll give it that. Upon first glance, it’s a strong trailer. It’s got some unique imagery. It feels different from films competing in the same genre space. And it’s got a great look to it. Peele knows how to create an event around his movies. This feels like something you have to see.

But if you look closer, there are some concerning things going on, a potential house of cards scenario. We have horses. We have men on motorcycles with mirror helmets. We have scary women with creepy fang mouths. We have… alien hands? We have a hole in the sky that sucks you up.

I’ve been doing this for some time. And when I see a bunch of things that don’t organically go together stuffed in a trailer, it almost always implies a film that will be messy. I hope to be proven wrong. But I already saw this brewing in “Us.” I mean, the bunnies, man. The bunnies! Great weird image for a trailer. Absolutely zero reason to include them in the film.

Remember when you saw the trailer for Get Out? You knew EXACTLY what the movie was you were going to watch. EXACTLY. Compare that to this film. Do you know the movie you’re going to see here? I don’t. And that has me worried.

Today I have a special treat for you, an interview with David Kessler, the writer of the new Johnny Depp film, Minamata, which comes out this Friday! The movie follows photographer Eugene Smith, who famously documented the effects of mercury poisoning on the citizens of Minamata, Kumamoto, Japan. A little backstory on this one – I consulted on the script many moons ago for David. David kindly credits me for helping him get the script in shape for what would, ultimately, become his first major writing credit.

1) Let’s start with you, David. When did you start writing screenplays?

I started writing screenplays in the mid-’90s while living in New York and working for myself as a graphic designer and a copywriter (WFH waaaaaay before it was a thing.)

My first script was a biopic about the 1950’s doo-wop child star Frankie Lymon. I had tracked down the former members of his group, The Teenagers, who were also (still) living in New York and very much not teenagers anymore.

After I had finished spec’ing the Lymon story, it was announced that “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was going to be made by the director of Selena, Gregory Nava, and that turned my screenplay into 120 pages of scrap paper.

2) Until the point when you wrote Minamata, how many screenplays had you written in total?

Five finished ones (the Lymon biopic, a terrible thriller I have little memory of, a coming-of-age adaptation of my terrible novel, a comedy based on dating, and a rom-com I re-wrote too many times for too long).

Plus 2 TV pilots, 4 TV specs (a Will & Grace, a Curb and two Seinfelds) and a short film. And a handful of feature treatments.

3) What would you say were a few of the most important screenwriting lessons you learned early on that allowed you to write such a good script in Minamata?

That you need to write bad scripts (see above) to get to good scripts. There are very few Sorkin-esque prodigies. It’s a craft. Your first chair is going to be a rickety bunch of wood but your 500th one will be much sturdier (and be worthy of selling).

And always be learning. I read your blog every day and still read screenwriting books and articles, watch YouTube videos about the craft, and screenshot little bits of advice I see on Twitter.

Plus, it may take a few genres / scripts to find what your “lane” is. Even though my first script was a true story / biopic, it took like 18 years to circle back to that niche.

Also, scripts and movies are supposed to make you FEEL something. If I didn’t scare you with a horror story or make you cry with my drama, I feel I failed.

And the bar is really, really high.

I once had a full-time job writing movie poster lines about 15 years ago – I read 2 to 3 scripts a day and these were things in production – Juno, Hancock, Enchanted, Stepbrothers – you realize you gotta be as good as the pros for studios to make your movie instead of Scott Frank’s or whomever’s.

Stepbrothers made me laugh so hard I couldn’t breathe in my cubicle (the testicles on the drums scene in particular). The Mist gave me nightmares after I had read it.

4) For my own egocentric needs, have there been any tips you’ve learned from the site in general that have helped you become a better screenwriter?

Oh tons — I bought your e-book years ago and I read the blog every day and screenshot a lot of your “what I learned”. And often go back through the archives. The Goal, Stakes, Urgency tip I come back to often and I even remember I think Jersey Shore was an influence on that somehow.

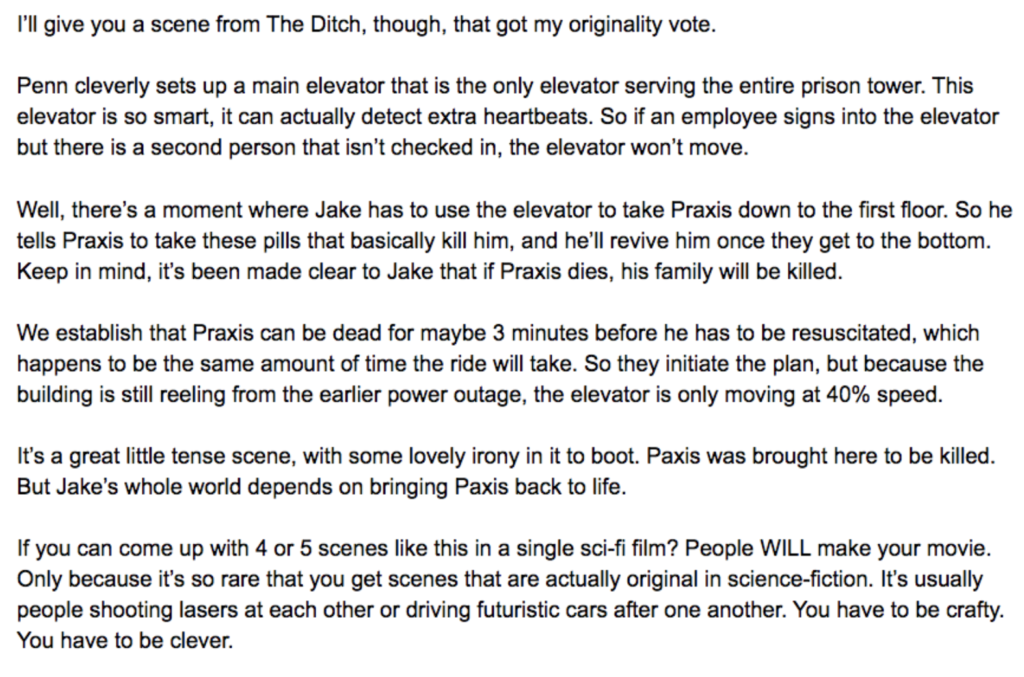

Here’s something I screenshotted back in 2017:

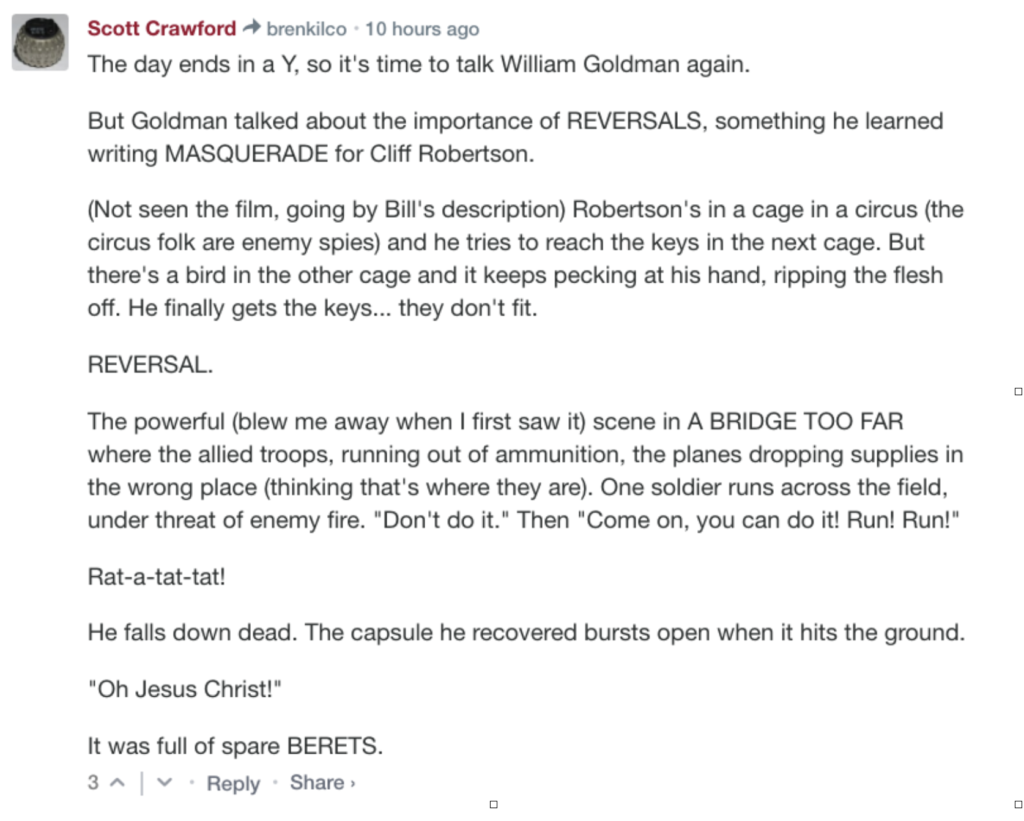

Another from the comments:

5) Now let’s get to the juicy stuff. Here on the site, I advocate for writing genre material with strong hooks. Minamata is a passion piece and, one would argue, the complete opposite of that. What advice would you give to someone who wants to write dramas or “low-concept” material? How do you write in this space and find success, like you did? Is there a game plan one can follow?

That’s hard to answer. Regarding the sale and having it been made, it’s like asking, “How do I win the lottery?” or “How do I find the love of my life?”

A lot of things need to fall exactly in place at the exact right time. I got very, very, very, very lucky.

Once I ran the numbers on the odds of my spec getting made with a movie star of Depp’s stature…I think the number came to .00004%.

I had caught Mrs. Smith (the widow of Gene Smith, who Depp plays in the film) at a time where she was willing to explore a movie deal again (she had been approached many times over the years and even had had meetings with Anthony Hopkins, Ang Lee and Scorsese in the ’80s or ’90s, with Hopkins to play her husband).

AND I had known a person from the comedy world from 13 years earlier who took the sketch class I had but the one right before mine but came to our class’s show – she gave it to her manager. This manager happened to have worked at a photo magazine in the 1970s, so the subject matter sparked her interest.

AND Johnny Depp knew of Gene Smith and admired him and his work because his friend, the late photographer Mary Ellen Mark, had taken Smith’s classes in the 1960s and had told Depp Gene Smith stories…

6) Quick question here: Did you know Depp liked Gene Smith ahead of time or was that pure coincidence?

That was a wonderful coincidence. I was told when Depp was in the office and the staff was updating him on the projects the company was developing, someone said, “Oh, it’s the story about this photographer named W. Eugene Smith who goes to — ” And Depp had (nicely) cut them off and said “I know who Gene Smith is.”

I had no idea about his relationship with Mary Ellen Mark or that she had taken classes from him, most likely at The New School, where I had gone to college.

7) Okay, got it. Continue…

All those people and moments had to have aligned for Minamata to get made (with Depp – see below for the attempted-Jeff Bridges path).

None of this is to say you shouldn’t write your passion project.

About half the projects on The Black List feel like passion projects (some have rights issues that inherently prevent a sale – like, say, the making of The Empire Strikes Back from the guy who played R2D2’s point of view or whatever.).

But they can attract attention. And demonstrate your ability and voice. I seem to recall getting some general meetings off Minamata before Depp’s company wanted it.

Being John Malkovich was probably a passion project / written to (further) showcase Charlie Kaufman’s unique voice. But then Spike Jonze asked his reps for the “weirdest script that could never get made” after he was sick of reading “regular” movie scripts. And Kaufman’s career took off.

So my point is, even if your script doesn’t get MADE, the script could MAKE YOU.

8) How does one get their script to an actor as big as Johnny Depp?

Through the normal, respected channels. My manager knew his “people”.

Someone took a recent script of mine (now granted, this person is married to a ridiculously famous person) and put it in the mailbox of their immediate neighbor, a famous actor, with a note. That didn’t work (despite them knowing each other).

But even if you don’t share a property line with a famous actor, don’t shove your script in their mailbox. It’s not how things are done.

But the Depp thing wasn’t a straight line. They initially passed but called back like 10 months later.

9) Okay, can you tell me about that? Did you find out the reasons why they initially passed? Was it one of those instances whereby the agent was making decisions for Depp and Depp never even knew about the submission?

Something like that happened with another project, but I didn’t find out what happened with Minamata until years later: The person at Depp’s company who had read it liked it and passed it up to his boss and they turned it down.

That first reader then later got a promotion and was offered to shepherd a project and he said, “I can’t stop thinking about that Minamata script.” And his boss said, “Well, if you feel so strongly about it, go for it.”

9) Also, I understand that you had Jeff Bridges attached for a while but that didn’t work out. What happened? Any cautionary advice you can give writers there?

Yeah, no one tells you this, but actors aren’t attracted to / “stick” to scripts – they are attracted and “stick” to directors who have a script or a project for them. They want to be directed. They want to work with the directors their peers have worked with (and maybe won their peers awards from working with those directors).

Look at Leonardo DiCaprio’s whole M.O. – for the last 20+ years he just exclusively works with A-LIST, top-shelf directors (Cameron, Eastwood, Allen, Scorsese, Nolan, Mendes, etc.). There’s no up-and-comers. He won’t “Bruce Willis” it with an up-and-comer like Tarantino like Bruce did with Pulp Fiction but he’ll sure work with him when he’s Tarantino.

On the “mailbox” script mentioned above, some big producers came aboard later and the first thing they did was go to directors they knew and to the reps of directors, not actors. The dream cast in our heads had to wait until a director was attached.

Scripts lead to producers which lead to directors which lead to actors which leads to studios / investors. All those elements are links in the chain.

So there were a few moments Bridges was interested, well, more like intrigued, but he wouldn’t budge if they wasn’t a director, even when there was a significant producer attached.

10) Okay, so did Depp only sign on when there was a director or did he come on first? (If he did sign on without a director, why do you think he went the opposite route of all these other actors you mention)?

The entire time the script was being developed at Infinitum Nil (Depp’s company), him starring was never discussed. And this was over a period of a year and half or more.

Now that I consider it, it may have been because there was no director attached.

And Depp himself did call director friends and associates and a cinematographer he had worked with for years to direct (him). He also hand wrote a note to another A-List actor / director to enroll him. Some responded to the material and Depp as Smith but had other professional and/or personal commitments.

When Andrew (Levitas) expressed an interest in directing it (I believe he was already attached as a producer), he and Depp met for a meeting that was supposed to be two hours which stretched into nine hours. I believe they talked about Smith, art, photography, visual touchstones, and their vision(s) for the material.

11) When did you find out that he was committing to star and what was that moment like?

I guess I found out when Andrew came aboard as a director — it was kind of stunning. Not only was I going to have a Johnny Depp movie — my first movie was going to be a Johnny Depp movie. I mean, I had grown up watching Edward Scissorhands, Gilbert Grape, Ed Wood, Blow, etc.

What was a particular thrill was, one of the producers (the original reader, Jason Forman — and later, another writer on it) sent me a photo of Depp in rough makeup at some point after that: a beard, a beret and holding a 35mm camera — Depp had had his makeup person do a test when there was a break in shooting something else.

I printed that out and tiled it so it was hanging over my bed, taped together in like 10 sheets of paper to remind myself it was real.

Still, I was always worried something would happen — like with financing or Depp’s schedule. You always hear about money falling through like with Dallas Buyers Club and other indie movies. I almost didn’t believe it was going to happen until I got paid and then like a couple weeks later was flying to Serbia, where we shot it.

12) Why do you think an actor such as Depp, who tends to be drawn to very interesting roles, liked this part so much? I guess I’m asking a bigger question here, which is: What kinds of characters are big actors interested in?

Smith was really in Depp’s wheelhouse – he was an artist to his core, rejected societal conventions, he had a fondness for drugs and alcohol (as did Hunter Thompson — who Depp played twice — and Jack Sparrow), and could be a real pain-in-the-ass and wasn’t afraid of making scenes but also had real heart. He was very larger-than-life.

But to your broader question: actors like playing interesting, complex, layered characters who say and do “cool” things. They love characters that are funny (Apatow characters), wicked smart (Imitation Game, The Social Network, Limitless, A Beautiful Mind, Good Will Hunting) – just memorable in some way.

13) Finally, is there some advice you can give from your personal experience that none of the film schools or screenwriting sites give on what it takes to get your script made into a movie? Does that “secret advice” exist?

There’s no secret – find unique ideas for movies (I just stopped working on 2 W.I.P.s when a recent collaborator / mentee of mine came up with a doozy and I pushed those two former ones hard to the side and I wrote the first act in 4 days), always be learning, find the HEART in your scripts / make me FEEL something, find and make friends in the same racket, read this blog, strive to be better – as good as the best, put yourself in a spot where you can be lucky and the odds can tilt slightly in your favor.

Minamata opens Friday in select theaters!

Genre: Political/Drama/Thriller

Premise: While looking into a client’s murder, a Los Angeles social worker stumbles on a political conspiracy in the wake of the 1987 Whittier Earthquake.

About: This script finished in the top 15 of last year’s Black List. Both writers have done a lot of short films but this is definitely their biggest success to date. Although there have been a lot of criticisms lobbed at the Black List lately, one thing they’re definitely doing is celebrating brand new writers. I don’t think there is any writer on this list that has had a long career.

Writer: Ben Mehlman & Filipe F. Coutinho.

Details: 131 pages

I picked this script to read for a very specific reason. As we all know by now, management companies have figured out a way to game the Black List. This is why you see the same managers on there year in and year out. I don’t begrudge them for it. They’re just working the system to get their writers noticed. And, in some cases, the managers have the goods.

But I always take those Black List entries with a grain of salt because I know the managers have reached out to the voters and made sure they voted for their writers. There are a couple of entries in the top 10 that benefited immensely from this. I’m not going to name names but there’s one writer in particular who’s made the top 10 twice now who, in my opinion, shouldn’t have even made the bottom 10.

I’m saying all of this because today’s entry is from a management company, Mazo Partners, that I’ve never heard of before. Which means these guys don’t have their own personal, “Black List Vote Marketing” team. Theoretically, that means this script actually earned its stripes. And it does sort of carry that vibe with it. There’s a Chinatown feel to its setup. It even has a cool picture on the title page. Should Robert Towne be shaking in his boots? Is his “best screenplay of all time” title about to be revoked? Let’s find out!

It’s 1987. While flying into Los Angeles, 47 year old Whittier social worker, Jackie, spots a 16 year old kid, JD, freaking out about the turbulence. She goes over to him, settles him down, but just as they’re about to land, everyone in the plane starts mumbling. Jackie and JD look out the window to see that Los Angeles is currently shaking from an earthquake.

When Jackie gets back to Whittier, she learns that her community has been hit the hardest. The state of California pledges to help out the folks of Whittier, bestowing them with 60 million dollars so they can rebuild.

Meanwhile Jackie and her new assistant, Tracy, get called in by the police as they have a 16 year old who was caught dealing coke (remember, it’s the 80s!), and what do you know – it’s JD. Because the earthquake has plugged up all the shelters, Jackie and Tracy are forced to send JD into some outdoor tent city, something neither of them are proud of.

Well their guilt is about to skyrocket as JD turns up dead several days later. For reasons I’m still unclear about, Jackie has zero interest in looking into her new plane friend’s murder and only does so because Tracy is so distraught about it.

Around this time, the infamous 1987 Black Monday stock market collapse occurs and a guy Jackie is sleeping with (named Guy), informs her that the money she invested with him is all gone. Furious, she screams at Guy. But Guy says don’t worry, he has a new “sure thing” investment where she can make all her money back and more. Just give him 30 grand. She says she doesn’t have 30 grand. And this is where the character actions in this script go bonkers – she borrows 30 grand through a loan shark to give to the guy who just lost all her money.

Jackie keeps digging into JD’s murder and eventually stumbles across the suspicious actions of Whittier’s Director of Treasury, Patrick Sy, who lost all 60 million dollars the state sent him for earthquake recovery in the Black Monday market crash. Long story short, Patrick never lost the money. He just said he did so he could use it for another project of his: gentrifying Whittier. A few more things happen but that’s the general gist of the plot.

We often talk about likability when it comes to our protagonists. But likability (or lack there of) are not the only things that influence whether we want to root for the hero or not. Another thing that influences us is stupidity. If our hero does something really stupid, we won’t root for them. When Jackie lost her entire net worth to this shyster con man and then willingly borrowed 30 grand from a loan shark at, probably, 50% interest, to invest in another money scam of his, I lost all respect for her.

You have to be so careful with the character creation aspect of your protagonist because your protagonist, unlike secondary characters or plot beats, is in EVERY SINGLE SCENE OF THE SCREENPLAY. So if we don’t like them for whatever reason, nothing else you write matters. You could have the greatest plot in the world. We won’t care.

I was also baffled that Jackie shares a very emotional and intense moment with this scared kid on a plane, and then when he’s murdered a few days later, she can’t be bothered to look into his case. It made an already frustrating character even more frustrating.

“Whittier” is clearly inspired by Chinatown, which is dangerous in so many ways, the most obvious of which being: How can you possibly compete with one of the best movies ever? Once you’ve made it clear to the reader that this is the movie that’s influenced you, everyone reading will compare your characters to the characters in that movie, your plot beats to the plot beats in that movie. And you will lose every time. Not because you’re a bad writer. But because a great movie is magic. It’s lightning in a bottle. It happens once every 2-3 years. You just can’t compete with that. Which is why I tell writers to go write something new, so people can’t compare it to anything.

But even if you strip away that argument, the stakes aren’t big enough for this story. When I found out that the twist was gentrification… I mean… I don’t know any movie plot where that’s going to move the needle. It’s not big enough. With that said, I’m not sure Chinatown’s stakes were that high (relatively speaking) either. But these days, the game is different. The stakes need to be high and feel like they matter.

Finally, when you’re tackling stories that have complex city government storylines, the writing has to be so sophisticated. We have to believe that you’ve actually lived in this world. Because if you haven’t, or you haven’t done years of research, it starts to feel a little keystone cop-y. Robert Towne knew that world soooo well. And his treatment of it was incredibly sophisticated. Today’s script didn’t feel that way.

I’m being harsh here, I know. It’s not a bad script. But those cornerstone pieces of a screenplay – the main character, the stakes – they need to be A+. They can’t be B- or C+. You can have some C+ secondary characters or subplots. But not for the stuff that matters. Those have to be a perfect or near perfect grade.

Unfortunately, this didn’t make the cut for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: For these more “upscale” murder-mysteries that have a big hook, the ending reveal needs to be bigger than the hook itself. So if your hook is an earthquake, your ending reveal has to be bigger than an earthquake. Gentrification does not feel bigger than an earthquake. Which means your plot ends with a whimper. If I may quote the famous marketing director of Porker Pipes, when it comes to your ending, “Go Big or Go Home.”

Genre: Action

Premise: A guy who builds boat engines for a living is recruited by a boat-racing crew who use the racing as cover for their real jobs – yacht pirates.

About: This is the big script that sold a couple of weeks ago. It came together as a project once Jake Gyllenhaal signed on. As I told you guys in the newsletter, you’re always one cool script idea away from getting a big flashy movie made. Glenn has been out of the game for a while. Look at him now.

Writer: John Glenn

Details: 124 pages

I’m always nervous when I review spec scripts. We don’t have many of these to celebrate. So I know, when they come around, it’s important that they’re good. If they’re good, it increases the chances the movie will be good. And if the movie is good, that means Hollywood will be buying more original material on spec. So I always feel pressure when I’m reviewing these, especially one as high-profile as this. This isn’t a rinky-dink million dollar horror spec. This is going to be a big production. So put your hands together and pray with me!

29 year-old Jessie lives in the middle of nowhere next to some lake. He builds boat engines and then races them. He barely makes any money off of this, though, which has put him in massive debt. Therefore, he isn’t surprised when an older guy named Marty shows up and tells him that he’s bought out his operation.

Marty informs Jessie that if we wants his business back, he has to come build boat engines for him down in Miami, where the real racing happens. Jessie reluctantly heads down to the Gateway to the Americas and meets the crew, which includes the hot-but-damaged Fiona, the slick Cuban, Nestor, the Nav systems expert, Bao, and a few other folks.

Jessie is surprised when Marty allows him to participate in a preliminary race, but Jessie shows that the big time is still above his pay grade, as he finishes last. That’s okay, Marty tells him. Because this racing thing? It’s all for show. What they really do is head out to international waters in these speedboats and rob gigantic billionaire yachts. And they’ve got the biggest one yet on their radar.

Jessie and the team prep extensively for the yacht known as the “Anastasia.” But boy are they surprised when they board this thing. There is over 100 million dollars of art on it, which they steal all of. By the way, the whole idea behind speed-boat heists is that the boats can race off in any direction and be 100 miles away within minutes, therefore confusing the boat’s occupants on where these pirates came from.

Except when you have a resourceful enough person, they can find out anything. And the person they just stole from was a Russian oligarch. He kills Marty and informs the rest of the crew he’s going to kill all of them AND their families UNLESS they can pull of the impossible. Steal him a 200 million dollar yacht known as the Cortez. That sounds like a dandy plan except for the fact that nobody knows who even owns the Cortez. It’s so steeped in dark crime, it might as well be invisible. But this is the bed our boaties have made for themselves. Now they have to lie in it.

Cut and Run is basically the boat version of The Fast and the Furious. But not The Fast and the Furious as it is now. The Fast and the Furious as it was in the first few movies, when it was grounded in reality. That’s ironic considering that Cut and Run is not set on the ground, but at sea.

The point is, it’s a self-contained story. Fast and Furious has basically become a giant TV series with these new episodes where nothing is really resolved other than a new physics fact, like that a car can now fly in space. To that end – that it was reality-based – I liked Cut and Run.

But Cut and Run has a flaw that it needs to figure out before it gets in front of cameras. Which is that the structure is wonky. Based on the summary of the plot I laid out, what’s the most exciting thing to you about this idea? It’s the Russian oligarch, right? Once he comes in, the story gets a hundred times more interesting. Well, what if I told you that the Russian oligarch doesn’t make his demand on the crew until page 85?

Come on.

That’s a midpoint twist if I’ve ever seen one. It needs to have happened 25 pages earlier.

I think I understand the issue they ran into. They had to set up Jessie. Then they had to set up the whole crew. Then they had to set up the fake racing operation. They had to figure out if they could trust Jessie. And then they had to introduce Jessie to their actual operation (they’re pirates). Then they have to do a long prep for pirating the Anastasia. Then they have to sell all the art they stole from the Anastasia. Then, and only then, could they introduce the oligarch.

These are the challenges you face as screenwriters. You’re constantly looking to fit everything in, and then, at a certain point, you realize there’s too much, and you have to make some sacrifices. Not everything is going to make it. This is healthy though. A screenplay is a battle of the best. If it’s not good enough or if it’s bogging the script down or slowing down the plot, you get rid of it.

My question, looking back on the script, is, “Do we need the racing stuff?” It doesn’t play into the story at all. And it takes up a lot of time. Why not just get straight to the crime so we can move our oligarch’s entrance up to the midpoint?

I suspect that the reason is those boat races are going to feature heavily in the marketing campaign, just like the street races in those early Fast and Furious movies did. Illegal boat racing in Miami? That’s a money shot right there. So I get it. But your big bad guy arriving with 40 pages left in the story? That’s not going to cut or run it.

Another thing that kinda bothered me was that Jessie wasn’t special enough. You always want to give your main character a ‘super power.’ I don’t mean in a superhero sense. But they should be great at something, which is why they’re needed. You can then play with that super power throughout the story. But all Jessie knows how to do is put an engine together. There needed to be more there.

With that said, the script is strong. I definitely felt like I was inside of this world. There is a lot of speedboat and yacht porn here. The level of detail is insane. And it doesn’t feel like the amateur versions of these scripts I read where the level of knowledge of your basic crew member is how many off-color jokes they know. Everybody here has a job. They all seem to know their job well. And that ensured that the suspension of disbelief never broke.

Now if they can just fix that structural problem, this could be a really cool movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Complicate the relationship. There’s a love story between Jessie and Fiona here. You never want these relationships to be too clean. Clean is boring. You have to constantly look for ways to complicate the relationship. One of the ways you can do this is by having one character find out a secret about the other, and then not reveal it. So after Jessie really starts to like Fiona, he gets a call from an old cop friend who he’s asked to look into the crew. The friend tells Jessie that Fiona is talking to the FBI. Keep in mind, Jessie is learning this just days before they go after the Anastasia. This form of dramatic irony allows for much more interesting interactions between Jessie and Fiona now. When Fiona wants to have sex, for example, Jessie has to do so so she doesn’t get suspicious. I don’t know what pretending to have good sex is like with someone who’s planning to send me to prison for the rest of my life, but I’d imagine it’s not an easy feat. But boy is it great drama for everyone else. Complicate the relationship!

I saw that Moonfall debuted in second place at the box office this weekend, with 10 million dollars. Moonfall, if you don’t know, was directed by Roland Emmerich, who directed movies such as Independence Day, 2012, and The Day After Tomorrow. Emmerich was quoted as saying, in a recent interview, that Marvel, DC, and Star Wars, have destroyed the movie industry, as they’ve made it impossible to create original content anymore.

Some people have pointed out that Moonfall is just another one of Emmerich’s “end of the world” movies and, therefore, isn’t that original either. However, they’re forgetting that Emmerich has a bunch of original movies he wants to make. But the studios are only going to give him money for the movies they know he makes successfully. And big end-of-the-world destruction movies are his bread-and-butter, so they’re the ones they greenlight.

This argument reinforces the question that has been dogging Hollywood for the last two decades: Where is the originality? It’s a question I think about a lot, specifically in regards to whose fault it is that we don’t have many original films. One could make the argument that it’s the fault of the moviegoers. If they don’t go see original movies, then Hollywood isn’t going to make them.

But I would place the onus on the creators. It’s our job to create something so irresistible that people can’t *not* go see it. This is something writers continue to get wrong. They’re so wrapped up in what *they* want to do that they forget they’re trying to create something *for others.*

Our flaw, as artists, is that we are all narcissists. It’s all about “me.” I need to prove “myself.” I want to make art people will love so I can feel better about “me.” Any artist who tells you they’re making art for others is a liar. They’re doing it so they can feel good about themselves. And it’s that approach that prohibits them from seeing movies through the eyes of the consumer.

IP is the exact opposite of this. Nobody involved in an IP property is worried about themselves. They’re only worried about making money. And because that’s all they care about, they’re able to see the world explicitly through the consumer’s eyes. What does the consumer want, they ask? They want that thing they’re familiar with. And it’s this very lesson that helps us understand how we can compete with IP.

The way you compete with IP is by understanding its appeal: familiarity. IP is playing on the fact that people have seen this thing before, are familiar with it, and therefore will likely want to see it again. Spider-Man understood this three-fold. It knew, not only, that you were familiar with Spider-Man, but that you were familiar with the three actors who had played Spider-Man. You went to see that movie due to the familiarity you had with the character and those three actors.

So, when you’re coming up with a movie idea, you want to find something that people are familiar with. A guy with a gun taking revenge on bad guys – that’s a setup audiences are familiar with. A haunted house – that’s a setup audiences are familiar with. The end of the world (yes, Moonfall) – that’s a setup audiences are familiar with.

Once you have the familiar, you add the unfamiliar. Or, it’s more relevant moniker: the x-factor. The x-factor is why concept generation is so difficult. It cannot be measured. It is one of the aspects of screenwriting you come up with on a gut feeling and then you hope, desperately, audiences connect with it.

The reason Moonfall did not do gangbusters at the box office was because potential moviegoers didn’t find the x-factor, the moon crashing into the earth, that interesting.

A key element of a successful x-factor is that it gives you scenes you haven’t seen before. The trailer I saw for Moonfall didn’t give me anything I hadn’t seen in any of Emmerich’s other movies. The reason this is important is because YOU MUST GIVE THE AUDIENCE A REASON TO COME SEE YOUR MOVIE. Three Spider-Mans is a reason to go see the movie. Familiar destruction set-pieces with some vaguely new elements aren’t a reason to go see a movie.

A recent example of “familiar with an x-factor” is the home invasion movie, See For Me. It has the familiar setup of a home invasion. However, it adds a twist. The girl in the house is blind and must rely on an app that connects her to a “seeing” operator, who can see the house through her phone, and tell her what’s happening so she can navigate danger.

Is this a gangbusters idea? Not really. I think it’s okay. But the writer *did* apply the concept-generation formula correctly. Familiar element (so you can compete with IP) and an x-factor (so you can differentiate yourself from others who’ve participated in this same setup).

Another famous movie that applied this formula was Paranormal Activity. The familiar element was a haunted house. The x-factor was that the whole thing was told through snippets of home video. Then there was Alien. The familiar element was the “monster-in-a-box” scenario. You’re stuck inside a location and a monster is hunting you down. The x-factor is that they moved the location onto a spaceship, set it in deep space, and changed the monster to an alien. Still another was Bridesmaids. It took the familiar: raunchy R-rated group comedy. Then added the x-factor: The group was made of all women instead of all men. Maybe the most famous example of this is Christopher Nolan’s Inception. Familiar element: A heist film. X-factor: Takes place inside someone’s mind rather than at a bank.

There is a more daring way to come up with a great concept but we’re walking into advanced territory here, people. You are about to leave the safety net that “familiar” provides for you. Do so at your own peril. In this riskier version of concept generation, you *only* use an x-factor. A famous example of this would be The Matrix. I don’t know what the “familiar” is here other than a guy who’s lost in life. But the x-factor is that he’s living in a simulation and can use that reality to bend the rules of space and time to kill as many people as possible. It’s a straight up x-factor idea.

Just remember that ideas without the familiar element have a bigger chance of seeming “out there” and “weird” to others. That’s because the familiar element GROUNDS the idea. If there’s nothing to ground the idea, we’re not even sure what we’re looking at. A recent example of this would be Tenet. It’s got the x-factor in spades: The ability to physically move backwards through time. But where’s the familiar? Is this a spy movie? Is it a globe-trotting playboy movie? Is it a crime movie? Without any ‘familiar’ to ground the concept, we’re never sure what we’re watching.

It should be noted I see all these ‘x-factor only’ ideas that never make it past a query letter. They’re often the worst ideas as they have nothing holding them together. So while the payoff is high (The Matrix was so awesome it still resonates today), the downside is below sea level. We’re talking Howard The Duck, Joe Versus The Volcano, The Happening, and Southland Tales. So if you choose to go down this route, do so carefully.

As you can see, I’m trying to prep everyone for the month of March, where I’ll be guiding you through writing the first act of a brand new screenplay. You have roughly three weeks to come up with a great concept. As I’ve stated many times before, a weak concept is at the top of the list for what’s holding your script back. So you want to put a ton of effort into finding the right one. Hopefully today’s post gets you a little closer. If you want professional feedback on your logline, I offer analysis for $25. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com. Just know that I’m going to be truthful!

Oh, and tomorrow, I’ll be reviewing a big recent spec sale that attempts to do the very thing I talked about today. We’ll see if it succeeds…