We take a look at the Black List script that got the writer the job for the now infamous upcoming movie, Cocaine Bear

Genre: Home Invasion

Premise: A pop star, a basketball player, and a bodyguard will need to defend against a crazed fan and his cronies who invade her home.

About: This script received 11 votes on last year’s Black List. It is written by Jimmy Warden, who wrote the sequel to Brian Duffield’s “The Babysitter” and, more recently, the script to the much buzzed about “Cocaine Bear.” I’m assuming this script got Warden the writing job for Cocaine Bear.

Writer: Jimmy Warden

Details: 97 pages

There is a group of people out there who are OBSESSED with the 1992 movie The Bodyguard starring Whitney Houston and Kevin Costner. That movie may be only second to Goonies in number of scripts I get that are trying to remake past films.

I kind of understand it. Whitney Houston and Kevin Costner were such an untraditional pairing and those untraditional pairs are often what audiences become mesmerized by. Still, I’m not sure I understand the obsession people have with this film, an obsession that has clearly influenced today’s screenplay.

It’s 1994 and 40-something William Bell is a bodyguard for 20-something Sofia, a Grammy-winning pop star who’s part Lady Gaga, part Carmen Electra, and part Ariana Grande. One night, a crazed fan named Duerson shows up to Sofia’s mansion and when Bell answers the door, Duerson stabs him.

Cut to six months later and we meet Sofia for the first time. She saw pictures of a Dennis Rodman like basketball player named Devante Rhodes and did the 1994 version of slipping into his DMs (she got her people to contact him) and now he’s over at her place for some hanky-panky.

It’s clear that Sofia does this all the time. In fact, she’s got a drawer where she keeps newspaper clippings of all the celebrities she’s banged. Which is too bad because Rhodes likes her and wants something more. While the two chat, Bell shows up for the first time in six months. He’s back on the job finally and, this time, he’s not going to take crazed fans for granted.

That new approach will be tested because it turns out Duerson has just broken out of the crazy ward! He’s teamed up with a giant scary man named J.H. and a psychotic French woman named Penny to go right back to Sofia’s mansion and take what he wants!

Bell then gets a call from his new girlfriend, who’s babysitting his daughter. There’s a strange man outside their apartment (it’s J.H.) and she thinks he’s going to harm them. Bell has to leave Sofia and, as soon as he does, Duerson and Penny charge into the house and take Sofia hostage. If you’re wondering why a 6 foot 8 monster of a basketball player is unable to protect Sofia from these two little scrawny gnats, join the club!

J.H. is somehow able to kidnap Bell, his girlfriend, and his daughter (does this guy have like 12 arms?), drive them back to Sofia’s house, all in time for Duerson to reveal his plan: He’s going to marry Sofia! He’s even kidnapped a minister to officiate the wedding. Will Duerson succeed? Or will crazy win once again??

Today I want to make a distinction between the three ingredients that make up a screenplay: Writing, Craftsmanship, and Storytelling. You need to be good in at least two of the three to write a good script. But your goal should be to become good at all of them. Let’s take a look at what each consists of.

Writing – Writing is the way in which you construct your words, your sentences, your paragraphs. It’s the prose you bring to the script to make it pretty, clear, and visual. When you read the description of a room, that’s writing. When you read the description of a character, that’s writing. This is usually what you see in the novel world. Since words are the final form of the medium, most published authors are good at it.

Craftsmanship – Craftsmanship is the ability to incorporate screenwriting-specific tools in an effortless invisible way. For example, understanding that you have to make your main character likable then writing a scene that conveys that likability – that’s craftsmanship. Understanding that a good scene needs to start late and end early – that’s craftsmanship. Coming up with a flaw for your main character, incorporating a theme, knowing where to put the inciting incident – all of that is craftsmanship.

Storytelling – Storytelling is the creative side of the equation. It’s not about being a wordsmith. It’s not about technique. It’s about how imaginative you are. Are you coming up with exciting plot points and story developments? Are you building a unique world that feels fresh and new? Introducing a surprising twist, like the Mary Jane father twist in Spiderman: Homecoming, that’s storytelling. Constructing a really cool spaceship chase, like we got in the beginning of Star Wars, that’s storytelling. The slow and careful infiltration of a poor family taking over a rich family’s home in Parasite, that’s storytelling. Any time you come up with a great scene idea or a great moment for your latest script, that falls under storytelling.

The reason I bring this up is because a lot of writers look at a screenplay as one big blob of writing and therefore don’t know how to pinpoint their weaknesses and improve them. But if you apply this separation, you can better understand where your weaknesses lie.

When I started reading Borderline, I was impressed by the writing.

The interplay between detailed visuals and playful commentary made the pages enjoyable to read.

But the craftsmanship in this script is sorely lacking. For example, there is zero attempt to make Sofia likable on any level. Why would we like a cold hearted bitch who uses people for sex, is disgusted by them when they show vulnerability, then disposes of them after a single night?

The reason this particular component of craftsmanship is so important is because the whole movie is about protecting this woman. If we don’t like her, why would we care if she’s harmed or not? You know what I mean? That’s not a minor craftsmanship screwup. That’s a MAJOR craftsmanship screwup.

Don’t get me wrong, you can get away with making characters a$$holes. But not if the entire movie depends on us liking them.

Another part of craftsmanship is character consistency. Duerson is introduced as an off-the-rails lunatic who can’t tell up from down. He seems to have stumbled upon Sofia’s house at the beginning of the story, almost by accident. Then, after he escapes from the mental institution, he’s all of a sudden Tom Cruise, putting together a Mission Impossible style attack team, complete with kidnappings, misdirects, and time-sensitive coordination. Which is it? Can the guy barely tie his shoes or is he a mastermind?

The storytelling side isn’t great either. Warden makes one interesting choice later in the screenplay (spoiler) when he kills off the main character. But every other creative choice feels rushed, like it was conceived during a feverish 24 hour writing session. Good storytelling has meticulous setups and payoffs. We can tell the writer has a plan that he’s carefully building towards. We don’t get any of that here. It’s mass chaos, a bunch of sloppy story beats carelessly cobbled together.

If you like home invasion movies, you might want to give this a shot. And I suppose if you’re making an argument for Warden, he’s got a chaotic off-the-rails style that some people dig, which is probably how he got Cocaine Bear. But I just found the script to be messy. There was no sophistication to the storytelling at all. I couldn’t get into it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: CHARACTER INTRO DELAYS. One pet peeve I have is when a screenplay mentions a character before they’ve been introduced. For example, sometimes I’ll read a script where we get a voice over from a character – let’s call him “Jason” – who I’ve never heard of until that moment. JASON V.O.: “I grew up in a small town outside Dallas.” Or maybe we’ll meet a character who hasn’t been introduced yet on the other side of a phone call. Or as one of the characters in a family picture we’re looking at. In screenplays, it’s important that when a character comes into a screenplay YOU INTRODUCE THEM PROPERLY. You give them a capitalized name, an age, and some description. This is a cue to the reader that: This is a new character in the script! If you do it any other way, you risk the reader being confused. Of them thinking, “Wait, who is this person? Were they already introduced? Why don’t I remember them?” However, if you absolutely must delay the official character introduction, Warden shows you how to do it. Here’s the proper protocol for a character intro delay.

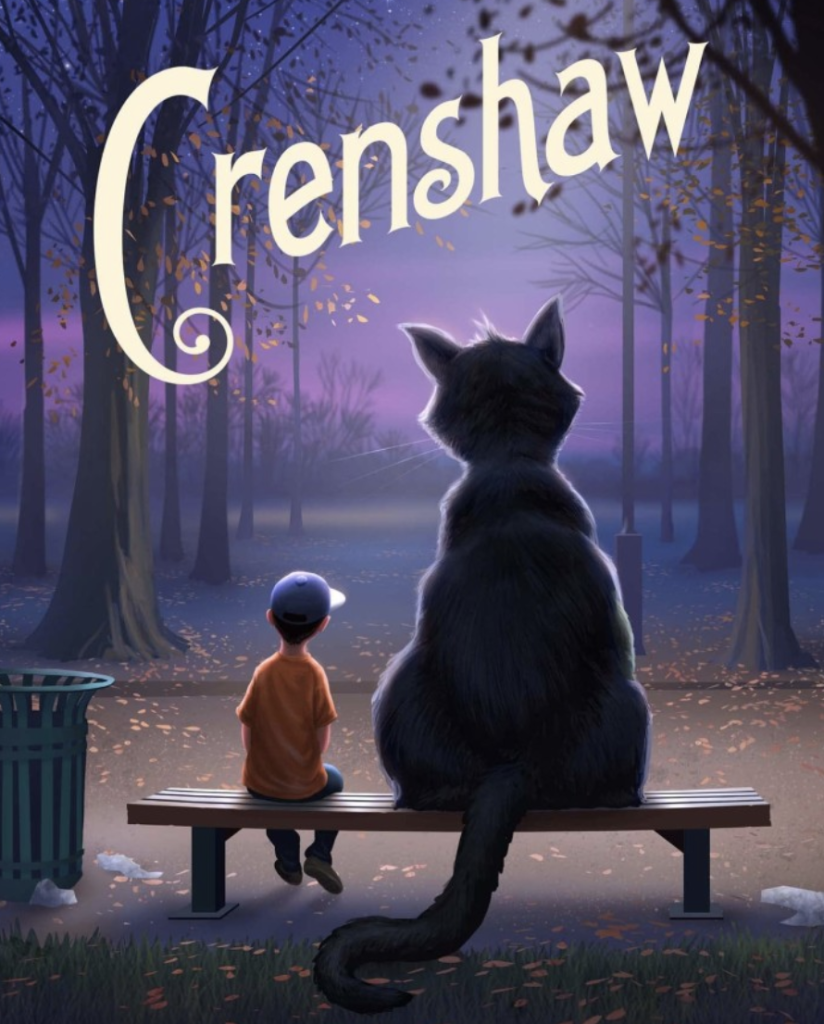

Genre: Family/Kids

Premise: A 10 year old boy deals with his family’s extreme poverty by reconnecting with his old imaginary friend, a giant purple cat.

About: This is the first movie James Mangold signed onto after the success of Logan. It comes from unknown screenwriter Frederick Seton. The story is based on a popular children’s book by Katherine Applegate, who won the 2013 Newbery Medal for her children’s novel, The One and Only Ivan.

Writer: Frederick Seton (based on the book by Katherine Applegate)

Details: 118 pages

I always find it interesting when directors known for dark material make kids films. Cause you know it isn’t going to be your typical kid’s film. Not to mention, dark kids films are the ones that stick with you for life. From Willy Wonka to Coraline to The Dark Crystal to Time Bandits to Where The Wild Things Are. That’s what I’m expecting when I see James Mangold (Logan) directing a family film.

By the way, I always tell screenwriters that if you want to learn how to write a screenplay, write a kid’s film. Kids movies teach you all the things you need to learn in order to write a good story. They require you to build sympathy for your main character, establish a character so that we instantly understand them (think John Connor hacking an ATM machine in T2), how to set up a goal that drives the story, how to establish high stakes, how to write in three acts, how to apply a theme, how to arc a character.

The great thing about kids films is that they’re a lot more forgiving because the audience isn’t as discerning. Let’s say you go over the top in establishing that your hero’s main flaw is that he’s selfish. You won’t get dinged on that compared to if you did so in an adult drama. Which makes this genre a great training ground.

“Crenshaw” follows a 10 year old boy named Jackson whose parents, Thomas and Sarah, are reallllllly poor. Jackson loves facts, which he spits out randomly to anyone who will listen: “Did you know that most adult moths don’t eat? Some don’t even have mouths. They’re just alive to make more moths and then they die.”

He, his parents, and his younger sister, live in a tiny house with tinier rooms and the tiniest of comforts. Both parents are unemployed, Thomas because he has MS and Sarah because she lost her job recently. What that means is they’re weeks away from losing the house, in which case they’ll have to, once again, live out of their old VW van.

One day, while Jackson is at the beach, he spots a giant purple cat surfing. This is Crenshaw, an imaginary friend from when Jackson was 5 years old. Crenshaw speaks with a British accent and cares mainly about having fun and helping Jackson. Jackson’s number one priority at the moment is getting a present for a friend’s birthday party. Because Jackson doesn’t have any money, he doesn’t know how he’s going to buy the present.

Meanwhile, Jackson’s parents are prepping for a garage sale, in which they hope to make enough money to keep their house. Sarah clearly doesn’t think the garage sale is going to work. She believes that the only reason they’re in this predicament is because of Thomas’s pride. He refuses to ask others for help. Which means, barring some miracle, they’ll be homeless again soon.

Oddly, Jackson and Crenshaw never discuss this problem, focusing instead on the way less important birthday present they need to find. Crenshaw seems to randomly show up every 20 pages or so asking for an update. And he isn’t very helpful in getting this present. In fact, Crenshaw isn’t very helpful at all. In fact, I have no idea why Crenshaw is even in this movie. Suffice it to say, this was a mess of a story that didn’t seem to have a plan or a point.

The industry parlance for figuring out the story in your movie is called “cracking” it. Well, they definitely did not crack Crenshaw. There are more problems with this screenplay than I can count. Luckily, there’s a lot to learn about what not to do in a family movie… or any movie for that matter. Let’s go down that list, shall we?

Jackson has zero influence on the story. He doesn’t do anything. He waits around, complains some. But he’s not contributing to the main problem facing him – which is that his family is going to be homeless soon. A main character who doesn’t act, who doesn’t have any control over where the story goes, is a weak character.

If I stopped there, that’s still enough to sink a screenplay. You need your main character to be active and to be doing things that solve the central problems he’s faced with.

There isn’t really a plot here. There are two things driving the story (technically speaking). One is the birthday present he has to buy. The other is them potentially losing their home. Let’s start with the present. The kid who invites Jackson to his party clearly likes him. For that reason, the gift doesn’t matter. You never get the sense that the friend will treat him differently if he comes without a gift.

This is why I say family scripts are great training grounds because this is where you learn this stuff. The stakes are low. So how do we make them higher? Well, what if this kid never wanted to invite Jackson? What if he only invites him because his parents make him? Under that scenario, Jackson’s present now matters. He wants this kid to like him. He feels like if he can get him the perfect gift, he’ll win over his friendship. That choice alone would improve this script by 20%.

As far as the homelessness, it’s dealt with in a really weird way, where it sort of pops up for ten pages then disappears for fifteen. It pops up again. Then it’s gone. Due to this inconsistency, it doesn’t feel important, which leaves very little gas in the plot tank.

You want to think of your screenplay as a car. But, unlike a car, which runs on regular gas, a script needs “plot point gas.” It needs a series of plot points to propel it along. Without those plot points, the car/screenplay isn’t going anywhere.

For example, in the recent movie, 8-Bit Christmas, which follows a kid who’s trying to get his dream Christmas present, a Nintendo Entertainment System, one of the plot points in the second act is the Boy Scouts are giving away a first place prize of a Nintendo to the scout who can sell the most Christmas wreaths. That plot point propels the characters to do something (sell wreaths) which pushes the plot along.

There don’t seem to be any plot points that develop along the way in regards to losing the house. It’s spoken of generally, leaving it up to the reader to figure out when they’re losing the house and what they’ll do afterwards.

I guess this isn’t surprising considering “Crenshaw” doesn’t even pass a basic storytelling smell test. Why have a titular imaginary cat that doesn’t affect the story? Doesn’t try to fix the problem? Doesn’t help the main character do anything? It’s bizarre how little both he and Jackson have to do in this movie.

Although there are all sorts of problems with this script, the main one boils down to a weak plot. The writer sets two goals – a present for a birthday party and a family about to lose their house – and doesn’t seem interested in resolving either one. For a story to work, the main character must be desperate to solve the problem. That will make them active. And their activity will ensure that there’s always something going on in the plot. If they’re only kind of invested, as is the case here, you’re going to put your audience to sleep.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a trick I’ve learned through reading a lot of family scripts. When you have an animated character, such as Garfield or Clifford or Sonic – mention a well-known actor/personality to convey what the character sounds like. To see how effective this is, let’s say I wrote a movie about a talking mouse named Lenny. “Lenny sounds like Will Ferrell.” “Lenny sounds like Morgan Freeman.” “Lenny sounds like Morpheus from The Matrix.” “Lenny sounds like Ryan Reynolds.” “Lenny sounds like Matthew McConaughey.” Note how each person mentioned gives the character a distinct identity that helps you immediately understand them. I wish Crenshaw would’ve done this because I never quite knew what he sounded like.

For 60 minutes, Hawkeye was a dud. Then something happened that turned it around. Today’s review discusses what that was!

Genre: TV Show – Superhero

Premise: After a college archer steals the suit to Hawkeye’s nemesis, Ronin, Hawkeye must protect her from a growing list of villains who want to kill her because they think she’s the infamous villain.

About: This is the FOURTH proper Marvel show to premiere on Disney Plus. The series is led by creator Jonathan Igla, who most notably was a writer on Mad Men. The principle director is Rhys Thomas, who teamed up with Seth Meyers to make Documentary Now. The show stars Jeremy Renner and Hailee Steinfeld.

Creator: Jonathan Igla

Details: 60 minutes (review covers first two episodes)

Hawkeye is a reminder that when it comes to telling stories, the more generic your setup, the harder it is to create any sort of original execution. You are drawing from the exact same well that hundreds of thousands of writers before you have drawn from.

This is why, when it comes to the four shows that Marvel has aired, Wandavision and Loki have a leg up on ‘Falcon and Winter Soldier’ and Hawkeye. The Wandavision setup was so unique that it had no choice but to give us unique situations. Ditto, Loki, with its wacky time-traveling parallel universe setup.

This is the dilemma Marvel is finding itself in by having so many stories. Where do you find the originality anymore? How do you give us stuff we haven’t seen already? Remember, the whole reason Marvel became the most successful franchise in history is because it was giving us stuff we’d never seen before. It was incorporating cutting edge special effects into a genre that hadn’t gotten that treatment, giving us pulse-pounding sequences like the airport battle in Captain America: Civil War.

But, these days, we’re so used to special effects in superhero movies, we need something else. Something new to excite us. And Marvel hasn’t been giving us that lately. I suppose the conversation in the Hawkeye pitch room was, “What about Christmas?” Is Christmas enough of a differentiating factor to make this show feel fresh? Let’s find out.

Kate Bishop is a 22 year old girl who’s really good at archery, something we see with our own eyes when, at college, she shoots an arrow at the college bell and, in doing so, destroys the bell tower. Why she did this, I have no idea.

Kate need not worry about that tower. Her very rich New York mother will pay for it. Yes, Kate has a trust fund bigger than the GDP of Moldavia. When Kate comes home for the holidays, her mom informs her that she’s marrying someone new, a sleaze-ball named Jack Duqensue. Kate doesn’t trust this guy and follows him to a rich people auction. When robbers arrive at the auction, Kate grabs this really cool looking suit that was supposed to be up for auction and starts running through New York City in it.

What she soon finds out is that this is Ronin’s suit, some notorious evil bad guy who used to terrorize New York. Because Ronin had a lot of enemies, people start coming after Kate. When Clint (Hawkeye) sees the suit on the news, he leaves his family, who’s heading to their cabin to celebrate Christmas in five days, to settle some past beef he has with Ronin.

Once he realizes it’s just a girl, he prepares to rejoin his family. But, by that point, too many people have seen Kate/Ronin and are coming after her. This thrusts Hawkeye into the protector role, which is great as far as Kate is concerned. Hawkeye is her favorite Avenger! Clint will have to solve this growing problem quickly less he not make it back to his family in time for Christmas. Will he succeed? Or is this going to yank him back into the world he so defiantly retired from?

There are actually a lot of solid screenwriting lessons in Hawkeye, the first of which is the value of an urgent storyline. We don’t typically see that in a TV show because it’s hard to keep a fast pace going episode after episode. But there are only six episodes here so it’s a little easier.

By establishing the need for Clint to get back to his family in time for Christmas, you give the story an energy it wouldn’t have otherwise had. Every setback puts more doubt into our minds that Clint is getting back to his family. When you do this well – build an urgent storyline around an emotional plot beat – it pays major dividends.

The question is, how do you do it well? You can’t just scream “I NEED TO GET BACK HOME FOR CHRISTMAS” and expect the viewer to get on board. You have to set these things up. So what we get is several scenes of Clint hanging out with his family before their flight, the most prominent of which is going to the “Rogers” musical together. If you want us to care about people rejoining each other, you must show us those people together and convince us that there’s a connection there. Too many writers ignore this. They think as long as the ticking time bomb is technically in place, that’s all that matters. No, you need to set up the emotional side of things.

The other smart move they made was understanding the limitations of the Hawkeye character and coming up with solutions for them. Let’s be honest. Hawkeye is the least interesting Avenger. Not only are his powers lame (he shoots arrows) but he’s got no personality to boot.

So here’s what the writers did. First, they LEANED INTO the lameness of the character. In an early scene, Kate Bishop chastises Clint for being boring. She encourages him to up his profile and think about marketing more. It’s done in a cute way and results in a fun little conversation. But, more importantly, it establishes that the show isn’t running from its weaknesses. It’s leaning into them. That’s always the better choice, in my opinion. If you ignore the elephant in the room, he only gets bigger.

The second more impactful choice is to give Kate Bishop gobs of personality. She’s fun, she’s self-deprecating, she’s a fangirl. They understood that two personality-less characters teamed together would’ve spelled doom for the series. They needed as much contrast as possible between these two and, therefore, went all in with “Fun Kate Bishop.”

And it works! The first episode of Hawkeye was barely watchable. But the second she meets Hawkeye, the series goes from a 3 out of 10 to an 8 out of 10. Let this be a lesson about the value of character pairings. If you can figure out the right chemistry between the two characters who have the most screen time together in your script, that can be the difference between an average and good script, or a good and great one.

That approach extends beyond the pairing as well. One of the clever realizations the writers had was that Clint is boring in a vacuum. However, if you can find situations where he’s uncomfortable, you can get fun moments out of him. One of the scenes in the second episode requires Clint to get the Ronin suit back from a guy. That guy happens to be fighting in a “Viking Reenactment Battle” in Central Park. Clint must reluctantly sign up for the battle and participate in order to get the suit back. It’s a funny scene.

And, finally, I have to give any screenwriter who says, “I’m not just going to save the cat. I’m going to save the cat with one eye” major props (It’s actually not a cat in Hawkeye, it’s a dog). In order to make Kate Bishop excessively likable, they didn’t stop at her rescuing a normal dog. This dog only had one eye. The craziest thing about this is that, despite being so transparent, it works. It amazes me, sometimes, what we writers can get away with.

Hawkeye is the most feel good show on the Marvel lineup. If you’re looking for a pick-me-up, look no further.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Put your character where they don’t want to be” may be one of the most powerful pieces of screenwriting advice there is. Again, the last place Clint wanted to be was at that Viking reenactment battle. Which is exactly why you wanted to put him there.

What I learned 2: Bring the villain closer. A villain inside the family (as is the case here, mom’s new fiancé) can often be more terrifying than a villain out in the wild.

Today’s newsletter is a special one. I discuss the frustrations of a rejection-based industry as well as the two types of scripts you should be writing to have the best chance at penetrating the industry. There’s been some Star Wars news in the past month so you know I’ve got to talk about that. I’ve got a once-every-year super Black Friday consultation deal. I’m only giving three of those away so hurry up and read the newsletter to find out how to get one. One of my screenwriting tips involves considering a high-powered genre that I don’t think any screenwriters know about. We’ve got a Brit List sighting. And, finally, I review a top 5 Black List script written by a longtime Scriptshadow contributor! Definitely worth your time to check this out!

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

It’s the Thanksgiving weekend which means I will be gone for the next four days! OR WILL I? Cough cough. Is someone sending a newsletter out on Thanksgiving? Cough cough. Maybe. #Keepaneyeout.

As we all know, Thanksgiving is a time where we willingly endure a nightmarish travel experience to reconnect with our families, to watch the Cowboys and the Lions while we drink cheap beer, and to participate in a meal that’s never as good as advertised. I mean, seriously, does anyone on the planet really like pumpkin pie? I’m talking even one person?? Can I have the phone number for whoever invented pumpkin pie please so I can give him a proper scolding?

Now, if you’re anything like me, you see the holidays as a sneaky secret time to get some writing done. After all the hugs and hellos and chuckles and uncomfortable political discourse, I burrow into a tiny room that nobody knows about and I start writing. You see, one of the underrated aspects about Thanksgiving is that it’s a highly emotional time. It’s not just the family stuff. It’s the travel. It’s the end of the year. It’s the reminder of previous holidays. Of old friends, old relationships. You don’t want to let all that juicy emotion go to waste. Highly emotional times tend to generate great material.

Which is why I thought I’d remind you that every screenplay requires two things in order to work. Without these two things, a script will die on the vine. They are the oxygen to your script’s lungs. What are they?

1) Give your characters non-stop things to do.

2) Have those things matter.

There is no good script in the history of screenwriting that doesn’t do these things. So let’s look at what they mean.

One of the most common mistakes writers make is they start off strong, with an aggressive first act, then as they make their way into the second act, they can’t think of stuff for their characters to do. They know the characters have to do something. But it isn’t clear what. So they write a bunch of “filler” scenes with characters sitting around talking or going places they don’t need to go. Eventually, they can’t even think of filler scenes anymore and they give up.

The way to avoid this is to make sure your character has a strong goal pushing him forward. This is true for big movies. This is true for small movies. But it’s far more common for the small movies to fail at this. That’s because with big movies, big goals are baked into the concept. Whether it’s the Avengers going after Thanos or The Rock and Ryan Reynolds trying to steal Cleopatra’s bejeweled eggs in Red Notice. The logline itself seems to tell you what the character’s going to be doing for the next two hours.

But what if you’re writing a character piece about a guy whose wife just divorced him and he doesn’t know what to do with his life? In these cases, the goal isn’t as clear. Which means you’ll likely violate rule #1: Give your character non-stop things to do. After Divorced Dan decides what to eat that first night and maybe after he does his laundry, what does Divorced Dan do?

Well, smaller movies typically use one of two things to drive the narrative. The first is a character who’s trying to get his or her life back on track. A good example of this is The Wrestler. The Wrestler is both trying to repair the broken relationship with his daughter as well as get ready for the big wrestling rematch with his nemesis. These two things always give him something to do. Each scene can push one or the other storyline forward.

The second thing small movies use to drive the narrative is money. This is why you see all these small town Coen Brothers films being about money. It’s to make sure the characters always have something to do (get the money). Hell or High Water is another recent example of small-town characters needing money.

But money doesn’t have to be a brief case with 100,000 dollars in it. Or a giant score from a bank robbery. It could be as simple as your hero isn’t able to pay his mortgage at the end of the month, which means he’s going to get kicked out. Once a character’s back is up against the wall, they have no choice but to act. Which means – you guessed it – they now have non-stop things to do. Every scene is going to be about getting that money.

So, to summarize, give your character a goal and they will always have something to do.

This leads us to the second rule, which is: THE THINGS THEY DO MUST MATTER. Let me paint a slightly adjusted scenario of the above movie idea. In our new movie, the hero doesn’t need money by the end of the month to pay his mortgage. He’s going to be fine either way. But let’s say he still wants money. So you put him through the exact same paces as the other character. He asks his friends and family for money. He asks for an advance at work. Maybe he tries to rob someone.

In every one of these scenarios our character is abiding by the first rule – he has “non-stop things to do.” However, there’s one major difference: those things don’t matter. How do we feel if his friend turns him down for money? We don’t feel anything because we know he doesn’t need the money. It’s got to matter for us to care.

Take one of my recent favorite films, Good Time. Brothers Connie and Nick try to rob a bank and Nick gets caught while Connie escapes. Connie has to bail out his brother within 24 hours or his brother gets sent to one of the most dangerous prisons in the state, where he’s not likely to survive. The next several scenes follow Connie trying to scrounge up the money to bail his brother out.

In one intense scene, he goes to his ex-girlfriend, who he recently ghosted, and convinces her to come with him to pay for his brother. It’s a great scene because he doesn’t like this girl anymore but she still likes him. So she’s asking him if this means they’re back together and he has to lie to her and say yes in order to save his brother. But the main reason the scene works is because THE SCENE MATTERS. We know that if he fails to get the money out of her, his brother could die.

That’s not to say all stakes must be life or death. But something has to be on the line in a scene for the scene to work. In my new favorite show, “You,” the main character, Joe, meets with his girlfriend’s best friend at a coffee shop. The best friend hates Joe and wants the girlfriend to dump him. Joe has to make nice with the best friend so that that doesn’t happen. There may not be a big chunk of money involved in this scene but the scene STILL MATTERS. If Joe fails to win over the friend, he could lose his girlfriend.

It’s really as simple as that. If you want to write a good screenplay, give your characters non-stop things to do and have those things matter.

Thanksgiving To-Do List: Get some writing done over the holiday weekend! We’ve got an ANYTHING GOES Amateur Showdown coming up in February so you’re going to want to be ready for that. I’ll be talking about that more as the year winds down. We’ve got a new Black List in a couple of weeks. We’ve got a maybe possibly probably newsletter hitting your inboxes in the next couple of days. And finally, whatever you do, do not – I repeat DO NOT – eat any pumpkin pie this weekend. We must stop the proliferation of this vile dessert. It starts with you.

HAPPY THANKSGIVING EVERYBODY! Gobble-gobble.