Star Trek is Star Wars for geeks. Guardians of the Galaxy is Star Wars for the cool kids. Is Foundation Star Wars for adults?

Genre: Sci-Fi/1 Hour TV Drama

Premise: When the galaxy’s premiere mathematician concludes, via a complex equation only he understands, that it is inevitable the Empire will fall, the leader of the galaxy exiles him to a remote planet and goes about trying to prevent his prediction from coming true.

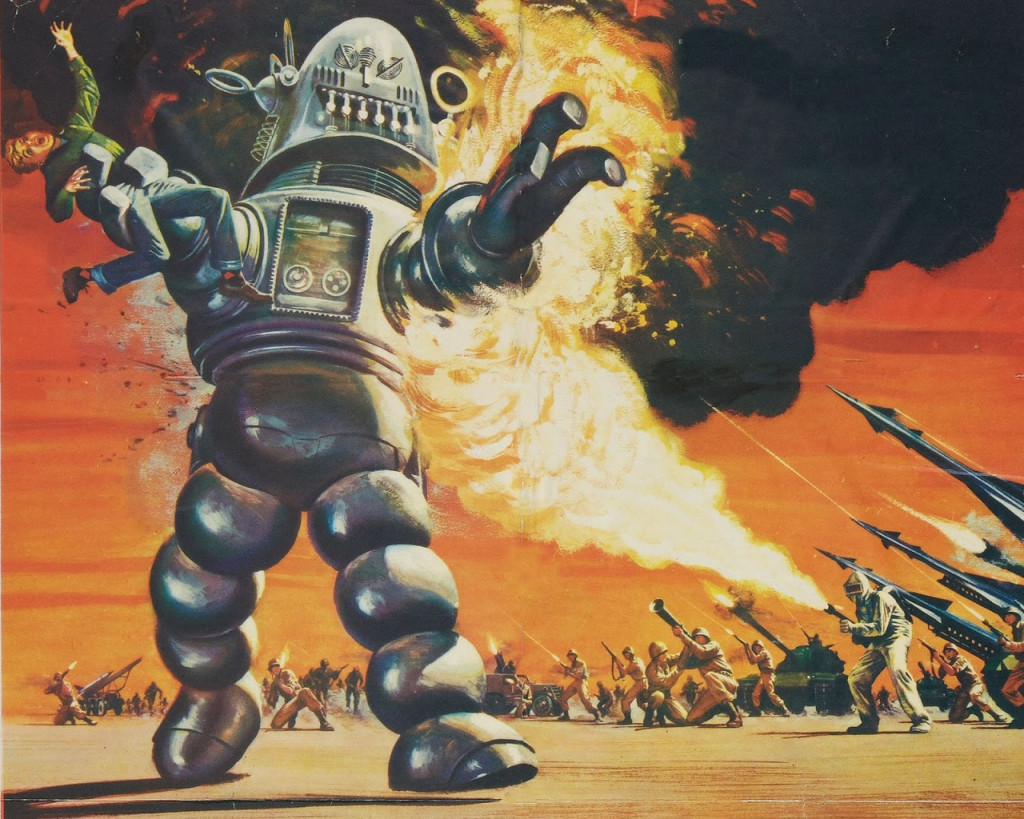

About: Based on one of the most famous sci-fi novels of all time, the expensive ‘Foundation’ is Apple TV’s official entry into the tentpole TV space (unless you count “See”). Foundation is a major influence on many of the sci-fi works we know today, including Star Wars. George Lucas borrowed some of the Star Wars terminology straight from Foundation, most notably, the ‘Empire,’ but also his obsession with clones. The series is being led by love-him-or-hate-him screenwriter, David S. Goyer (The Dark Knight, Man of Steel), who calls the Foundation show the biggest writing challenge of his life, as the narrative will span thousands of years.

Creators: Josh Friedman and David S. Goyer (original novels by Isaac Asimov)

Details: Pilot episode was about 65 minutes

The only reason I bought the Apple TV+ service was to see this show. Then I found out it wasn’t coming out for another year and a half! So I waited and I waited and I waited and then I waited some more, and FINALLY I got my Foundation.

Meanwhile, I have no idea if anybody else besides me is interested in this show. I think it looks amazing. Star Wars for adults if it nails the execution. Yet I haven’t heard anyone else mention Foundation, which makes me wonder just how many Apple TV subscribers there really are. Or maybe it’s just not as buzzy of a show as I think it is. Let’s find out together.

Foundation is set in the far off future after the entire galaxy has been populated. This galaxy is run by a clone emperor named Brother Day. Brother Day keeps cloning himself so he can rule forever. He actually rules alongside his older clone, who was once in his position, and a younger clone, who will eventually take his position.

Off on a remote planet we meet a brilliant young mathematician named Gaal Dornick. Gaal has been called to the central planet to work alongside the most accomplished mathematician in history, Hari Seldon. After a light-years long flight, she arrives at the capital city, meets Hari, who instantly tells her, “Oh yeah, um, I forgot to tell you. They’re going to arrest you tomorrow.”

Gaal is like, “Excuse me???” Hari explains that in his latest equation, he has predicted the fall of the Empire. It is inevitable and will last millennia. He knows Brother Day won’t like that, so he’ll arrest Hari and anyone working with him. Sure enough, the next day, Gaal is arrested. She is told by the Empire to look at the equation and, regardless of it is right or not, to say it is wrong. That way the entire galaxy doesn’t freak out.

But in a courtroom battle, Gaal confirms Hari’s findings. Brother Day is brother pissed. Hours later, the giant space elevator that doubles as a landing port for all ships coming to the planet, is blown up by two terrorists, and falls onto the planet, killing upwards of 100 million people, seemingly confirming Hari’s prediction.

At the last second, Brother Day has a change of heart and exiles both Gaal and Hari to a remote planet on the outskirts of the galaxy. They are to work on a solution to the Empire’s demise. When they find one, they can come back. And that’s the end of the pilot episode.

One of the issues with tackling stories that have an enormous scope is getting lost in the scope. The writing becomes more about the world building and “showing off” than it does telling a story that actually keeps people entertained.

The first 30 minutes of Foundation operates this way. It’s powerful people in big rooms saying random things about situations we only barely understand. There’s no form to any of it. And, therefore, no function either. It is 30 straight minutes of ‘who the hell cares?’

But then the court room scene comes. This is the scene where Gaal will either lie and say that Hari’s conclusion was incorrect, in which case she’ll go free and live a normal life, or she tells the truth, which is that Hari is right, in which case she’ll likely be killed.

You’ve finally written a compelling scenario. A courtroom scene has form. I understand a courtroom scene. I didn’t understand 1000 people standing in front of Brother Day as he babbled on about the warring factions of the Fifth Segmentia of the Clororo District. That scene has nothing in it that’s dramatically relevant.

A courtroom scene, meanwhile, is not only something I’m familiar with (and therefore I understand what’s happening), but something with consequences. The stakes of the scene are someone’s death. THAT’S how you invest readers. Always remember to create scenarios that a) people understand and b) have consequences.

Another scene that I understood was two terrorists blowing up a significant structure. Terrorism for a cause is something we’ve seen in our lifetimes. That’s why I’m familiar with and understand it. Again, you have to place us inside scenarios that we understand in order for them to have a dramatic effect.

How am I supposed to understand, or care, about two planetary representatives staring at a wall of art? Staring at a painting on a wall while saying random things to each other has no dramatic consequences whatsoever. It’s a banal empty scene. And yet that was typical of the scenes early on in the pilot.

I understand getting exiled to a planet. That makes sense to me. I’ve seen that before. I know that’s happened to leaders throughout time, like Napoleon. So it was a scenario, again, I could participate in.

In setting up this world for the audience, Goyer got lost in the details and forgot to create dramatic scenarios that actually entertained people AS WELL AS informed them. You can’t make that mistake with a pilot. People just don’t have the time in 2021. Do you know how many other shows there are out there? The list is endless. You can’t do anything that makes someone think, even for a second, “I wonder what else is on?” I seriously considered ditching this show 30 minutes in. The only reason I kept watching was because I was going to review it. But I’m sure others, after watching the opening, said, “What is this stuffy boring sci-fi bullshit?”

The courtroom scene and the space elevator destruction ended up saving the pilot but the weak first half sets up some concerning questions about where the series is headed. Is it a good idea to create a show without a single happy character? Without any humor at all? A show needs balance. Or at least a small variation in tone. The tone here is 5th gear super serious at all times. Has there ever been a show like that that’s succeeded? I’m asking honestly.

This brings me back to Friday’s Amateur Showdown winner where I had a similar problem with the script. The family was really serious. The script took a really long time to get going. I think writers continue to use the excuse of, “Well, I had to set up the characters and the story” to justify it being boring.

Don’t do that. Do both. Set up the characters and story WHILE you’re entertaining the audience. It doesn’t have to be Sophie’s choice.

Star Wars is one of the best examples of this. Darth Vader isn’t Brother Day when we meet him, casually strutting around his palace, looking concerned about the state of affairs. He’s too busy relentlessly pursuing the people who stole the Death Star plans. He’s active. We’re meeting a character but we’re also BEING ENTERTAINED while doing so. I honestly believe that the only reason writers don’t do both of these things at the same time is out of laziness. It’s easier to set up rather than set up and entertain.

Despite me sounding like I didn’t like Foundation, I’m still hopeful. I really want this series to work because I think a Star Wars for adults would be awesome. The Mandalorian has shown me that it’s more interested in satisfying the younger fans than the older ones. So it would be cool if I had something targeted towards my demo.

Is this show on anyone’s radar? Am I the only one watching it? Do any of you watch anything on Apple TV? I’m curious because I never hear anyone talk about Apple other than Ted Lasso so I’m wondering if anyone even knows it exists.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Offer foreknowledge to the reader to create a more compelling scene. There’s a scene in the first half of Foundation where Brother Day visits an older artist (or maybe he’s an art curator – it’s unclear) and starts chatting with him. We gradually get the sense that he’s unhappy with this guy for something that happened recently, although it’s unclear what that something is. Finally, at the end of the conversation, he shoots and kills the man. The scene is a dud because we were given no prior information on who this man was. We had no idea Brother Day was even coming to see him until the scene started. In other words, we didn’t have nearly enough information to actively participate in the scene. We needed the writer to give us more info so that when Brother Day walked into that room, we knew he suspected this guy of something and we knew that he was thinking of killing him. That way, we would’ve felt suspense as well as fear. But when you don’t tell us anything ahead of time, we’re lost in the scene, especially this early on when we don’t know any of the characters or what they’re up to. It was a miscalculation and one of the reasons the first 30 minutes felt like stuffy setup rather than an entertaining show.

I continue to have issues with my E-mailer so if the newsletter is not in your Inbox, check your “SPAM” and “PROMOTIONS” folders.

In this month’s newsletter, I talk about Warner Brothers giving Christopher Nolan the heave-ho. Francis Ford Coppola finally making his Citizen Kane with his own money. I give a Kinetic update. I exclusively announce THE NEXT SHOWDOWN. Something tells me it will be a ghould ole’ time, wink wink. I discuss a new unexpected million dollar spec sale, my strange obsession with Dear Evan Hansen, my ongoing infatuation with everything White Lotus, the latest Marvel show trailer, and a script review of the project John Boyega just walked off of set on. You’re not going to want to miss it!

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

Today’s script takes cues from both A Quiet Place and Pitch Black. Is it on par with those screenplays?

Genre: Sci-Fi Horror

Premise: When a photosensitive alien force blacks out the sun, a dysfunctional family must survive together in a perpetually dark world full of predatory creatures, while trying not to lose the only thing that can protect them: the light.

Why You Should Read: Black Sky is my first sci-fi screenplay, though it’s as much a horror/thriller and family drama as it is sci-fi. Definitely a sci-fi concept though. I see Black Sky as a possible franchise, and/or a TV series. It’s in the vein of A Quiet Place, Signs, Bird Box, and The Walking Dead. I wrote it to be produced on a low-budget, but ironically a couple of people who’ve read it compared it to War of The Worlds. I’m not sure about that but I was pleased by the comparison and in any case I believe it can be produced low-budget regardless of that comparison. My last two screenplays, both set in a car and written to be made for a micro-budget, were recently #1 and #3 on the black list paid platform top list and consequently I have a shopping agreement with a great company in LA for one of the scripts, and I’m in negotiations with a producer who’s made more than a dozen movies on the other script, so being high on the black list really made a difference and hopefully I’m on a bit of a roll and can get representation now. In the meantime, it’d be great to get feedback from Scriptshadowers and possibly Carson if it were selected for Sci-fi Showdown.

Writer: Sean McConville

Details: 107 pages

Readability: Medium to Fast

After months of waiting, we FINALLY have our Sci-Fi Showdown winner! BLACK SKY. I like everything about this submission. I like the title. I like the logline. I like the marketability. I could see the poster and the trailer for this script. But the submission still has one last test to pass. Do I like the script itself? Let’s find out!

38 year old Aiden has taken his family on a vacation into the Moors, a remote rural area in England (I’m assuming). Aiden’s family isn’t doing so hot. He’s got a wife, Lara, who’s wanted to leave him ever since he cheated on her. He’s got a 17 year old step-daughter, Riley, who’s never liked her fake father. The only drama-free member of the family is 8 year old Conor, who very well might be the smartest of all of them.

While Aiden and Conor are out fishing, they see a strange black substance slowly move across and block the sun. Spooked, they head back to the cabin, where they find that all of the electricity has been turned off, as well as all access to the rest of the world. Freaked out, Lara demands that they drive back to London. Except that the always lazy Aiden hasn’t filled up the gas tank. Pissed off, Lara says they’ll just sleep here tonight and see what’s up in the morning.

But then the morning never comes. Or, it does come, but there’s no sun. Just blackness. Just night. Confused, the family decides to go into the nearby town where they find all the stores have been raided. Now that they know it’s bad, they head to the gas station, but the gas station is closed. Out of options, they drive back to the house. As they scramble around the property to get supplies to hole up, we see black inky creatures in the shadows that seem to dart away whenever there’s light. Unaware of these camouflaged aliens, they start a fire in the fireplace so they don’t freeze to death.

After a while, they notice that the military has blasted a hole in the dark sky above the town of York (about 60 miles away) so light shines down on it, keeping the people safe. Aiden and the family think if they can get to that town, they’ll be good. But that means finding gas! So they set about going to the neighbors’ houses to steal their gas. However, guess who’s waiting for them? That’s right. Aliens!

I’m really torn by Black Sky because, from page 65 on, it gets pretty darn good.

But I’m not going to lie. I fell asleep twice while reading the first 65 pages. And that’s because those 65 pages are too casual an exploration of the idea. To put it in analogous terms, the first 65 pages never go above third gear.

You have to remember this simple rule as a writer: Make it so they CAN’T NOT KEEP READING. Make it impossible for them to say, “Eh, I’ll get back to it another time.” You have to yank them in and never let them go, especially in this genre, which is built on suspense, scares, and thrills.

We see aliens throughout the first 65 pages of Black Sky. They’re usually in the shadows, watching from afar. But they never DID anything. They just sat around and watched. So why would I be afraid of them? Let’s not forget the very first scene in A Quiet Place has a 7 year old boy getting eaten within a second of making a noise. That’s how you create fear.

The plotting here is too slow and too unimaginative. We hang out at the house. Then we go out to the tree. Then back to the house. Let’s go to bed even though the world is ending. Let’s go get some gas. Eh, we couldn’t find any. Let’s go back to the house. Let’s go back out to the tree. It felt like a writer trying to come up with the next scene location on the spot. It didn’t feel like the story was being planned. Have I had a scene in the bedroom yet? No. Okay, let’s go there.

My guess is that Sean was a lot more interested in the family drama than he was the alien drama. He puts a lot of emphasis on this dysfunctional family. In theory, this is a good idea. You want your characters to be complex. You want your relationships to be complex. To that end, Sean did a good job.

But here’s the irony. Everyone was so miserable in this family that I didn’t really like any of them (besides Conor). I definitely didn’t like the wife. The teenaged daughter was ungrateful and couldn’t stop complaining. And Aiden I could never get a feel for. He’s a good dad to Conor. But he cheated on his wife. He’s also such a schulb that he doesn’t fill up the car with gas.

And that’s another big problem with the script. The entire plot hinged on them finding gas. I don’t think this is the kind of movie where finding gas should dictate everything. Cause let’s be honest. Gas is everywhere. Nobody’s alive anymore so you can steal it from a car. We also find out they have gas in their generator. That irked me because everyone’s desperately running around trying to find gas when all I’m thinking is, “It shouldn’t be this hard to find gas. The only reason it is is so the writer can have a story.”

We do this all the time as writers. We convince ourselves that a plot thread works when, deep down, we know we need something better. Black Sky is so dependent on this finding gas storyline that it easily could’ve been titled, “Gas Search.”

What’s so frustrating about Black Sky is that the moment I was about to mentally give up on it – on page 65 – is the exact moment where it starts to get good. The aliens start attacking them which means now they’re not just walking from room to room talking to each other. They’re actually fighting for their lives. They’re actually having to make choices that affect their immediate safety.

But it was a case of too little too late. I can’t be bored for an hour in a movie then just turn on my interest. Actually, that’s not true. It just happened with Malignant. But that’s because Malignant had a killer twist and the best third act ever.

If Black Sky wants to be a good script from start to finish, Sean needs to rethink those first 65 pages. I’m guessing he’s banking on the slow-burn approach but like I’ve told people here before, there’s slow burn good and there’s slow burn boring. This is slow burn boring. We need more going on at the cottage so it isn’t just a bunch of boring scenes with people talking. And we need a much better goal than to find gas. It just feels too tiny for the situation.

Black Sky has its moments, especially later on in the script. But everything that comes before page 65 needs to be turbo-charged. We need a lot more going on. I wish Sean good luck with it. What did all of you think?

Script link: Black Sky

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Give your creatures the advantage. One of the subtle differences I noticed between this and A Quiet Place was that the Quiet Place creatures seemed to have a strong advantage over the humans. If you made even the tiniest sound, they could kill you within seconds. Conversely, the monsters in Black Sky always seemed to be on the defensive. They’re always hiding in the shadows. Scared of even the tiniest amount of light. I didn’t fear them much at all (until the end, when they all of a sudden become aggressive). Had we given them a stronger advantage, this script would’ve been a lot scarier.

These sci-fi submissions did not make the Science Fiction Showdown. Find out why!

One of the most frustrating things that writers go through is sending their scripts out there only to get rejected time and time again, and having no idea why. I had two instances this week where writers e-mailed me and wanted to know what they were doing wrong.

In one instance, a writer said they had sent their script out to half a dozen contests but that it didn’t advance in a single one. What was wrong? The other writer conceded that his concept wasn’t very good but that if I’d read the script, I’d realize how amazing it was. I sympathize with both of these writers. You spend months, sometimes years, working on a script and then nobody seems to care. You feel like you’re doing something wrong but you don’t know what.

Well, I’m going to clear it up for you. There are two areas you have to execute to break into this business and they must be completed in order. One, you must execute the concept (come up with a compelling concept that makes people want to read your script). And two, you must execute the script (write a script that entertains from the first page to the last). Except for rare situations, it doesn’t work when you only execute one of these.

The reason you need to execute the concept first is because it doesn’t matter that your script is genius if nobody wants to read it. A lot of writers turn a blind eye to this reality. They convince themselves that as long as they write a great script, it won’t matter. Well, it does matter because you need to get people to read the thing and they’re not going to read the thing if it sounds boring.

If you pass that test, the hard part begins because, now, you have to keep people entertained for 110 straight pages and even the best writers in the business struggle to do that. Most amateur screenplays I read fall somewhere between “sub-par” and “average.” That won’t do. I’ll say it again. As an amateur writer – someone who isn’t getting the benefit of the doubt – you have to entertain the reader on page 1, page 2, page 3, page 4, page 5, all the way to page 110. You don’t get any pages off.

But again, none of that matters if you don’t get the concept right because people aren’t even going to give you their time if you don’t do that. Look at the concept that won Amateur Showdown last week. “When a photosensitive alien force blacks out the sun, a dysfunctional family must survive together in a perpetually dark world full of predatory creatures, while trying not to lose the only thing that can protect them: the light.” That’s a movie concept right there. You can see that trailer. You can see that movie making money.

I don’t think enough writers think of concepts that way. They come up with something they think is cool and turn a blind eye towards what anyone else thinks of it. To that end, I’m going to go through some of the sci-fi concepts that were submitted to me for Sci-Fi Showdown and take you into my head as to why they didn’t pass the “concept” test. I’m hoping to not only help the writers who sent these in. But to show you, the readers, how people receive ideas and what makes them say yes or no. Let’s take a look…

Title: The Billionaire Battle Royale

Genre: Sci-fi, Action, “Dystopian”

Logline: 2045–in a world that has combated wealth inequality by hosting an annual fight to the death between billionaires, the inner circle of the world’s richest man tamper with the event to ensure he loses.

Analysis: This one falls under a category I occasionally see with concepts which is that it’s presented as a serious story when it sounds like it could be a comedy. I imagine 2045’s version of Elon Musk fighting 2045’s version of Jeff Bezos and there is nothing in that scenario that makes me think I could take it seriously. On top of that, the central conflict isn’t very interesting – one of the teams ensures their guy loses. Feels like you could come up with a way bigger conflict than that. There are shades of The Purge and Hunger Games here that might entice some. Curious what others think of this idea.

Title: Surrogate

Genre: Contained Sci-Fi/Thriller

Logline: To pay for an exhibition, a starving fine art photographer agrees to be a surrogate for a wealthy couple, but confined to a lavish house, her mind and body start to unravel.

Analysis: One of the more common movie concepts I get sent is characters going crazy. What I’ve found is that these scripts are extremely execution-dependent. Coming up with a story where someone gradually loses their mind for 100 pages is a lot harder than you think. In my experience, almost all of these scripts go off the rails, becoming muddy and uninteresting the further the protagonist progresses into crazyville. Also, this logline isn’t doing the concept any favors. It doesn’t tell us WHAT is going on in the house to cause her descent into madness. Which means that the only thing we have to go on is that she’s stuck in a house. That isn’t very compelling to me which is why I didn’t pick this.

Title: Astaroth’s Children

Genre: Sci-Fi/Horror

Logline: When stranded on an abandoned space station, a crew of military freelancers encounter the survivors of a horrific scientific project gone wrong. Unable to contain the effect, an agoraphobic engineer must destroy this threat to humanity’s existence.

Analysis: The reason I passed over this is pretty simple. It sounds like every video game ever. Resident Evil. Doom. Halo. You can’t just repackage the same movie (or game). You gotta give us something different. There wasn’t anything in this concept that made me think I haven’t already seen this story before. That’s something you gotta think about when you’re putting together your logline (preferably before you write the script). Does this sound too much like other movies we’ve seen? If so, you may want to think twice about writing it.

Title: Infiction

Genre: Sci-Fi

Logline: A female con artist is allowed to ply her trade against an alien group in human form to help them grasp humanity’s evolutionary need for fiction.

Analysis: I read this logline several times and struggled to understand it. By the way, this is one of the biggest reasons to get a logline consult. To see if your logline is clear. A female con artist is allowed to ply her trade? Her trade of con-artistry? Or a different trade? “against an alien group in human form” – had to read that several times to understand it. “to help them grasp humanity’s evolutionary need for fiction.” The stakes of the story are that aliens want to know why we write books like Harry Potter? The stakes need to be much higher than that for a movie.

Title: Future Shock

Genre: Sci-Fi Thriller

Logline: New York’s last ‘accountable’ cop has one night to find four prison-escapees fitted with pacemakers designed to kill them if they leave the city.

Analysis: The idea seems to contradict itself. Four people have escaped prison. Presumably, their goal is to flee the city. A cop must stop them from fleeing the city. But why is he needed if they’re all going to blow up the second they try to leave the city anyway? Problem solved, right? Unless this is a movie about saving bad people from dying. But that doesn’t seem to be the writer’s focus. Wouldn’t this work better if one of the prison escapees was the protagonist? Also, don’t put quotes around words unless it’s clear why you’re doing so. I’m not sure why ‘accountable’ needs quotes around it. This may seem like a nitpick, but every single script I’ve read where someone has put quotes around a random word in a logline has been bad.

Title: E-TEN

Genre: High concept/Sci-fi/contained thriller

Logline: An insecure hotel janitor and 5 other guests are held captive in a small library where a mysterious voice tells them to find the perfect political system for humanity under 90 minutes if they don’t want to be gassed to death. Things get out of control as they soon realize the game is hiding a traitor…and an axe.

Analysis: There’s nothing realistic about this setup. Why would someone pick six random people and tell them that if they don’t solve something that nobody’s been able to solve in 4000 years, they’re all going to die in 90 minutes? Why would you think these people were capable of doing this? And why so dramatic? If coming up with the perfect political system is important to you, wouldn’t you want to give them an adequate amount of time to do so? This concept didn’t make sense to me.

Title: Earthbound

Genre: Sci-fi

Logline: When an inmate in a prison orbiting Neptune finds that she’s pregnant, she begins a desperate attempt to escape and reach Earth, a place she’s only heard rumors about.

Analysis: This is one of those ideas that kind of sounds like a movie. But my first question after reading it was, “Why did you wait until now?” If getting to earth was important to you, then try to get to earth regardless of whether you’re pregnant or not. Now, if what you’re saying is that she needs to get to earth because they’re going to terminate her baby the second they realize she’s pregnant? Or if she knows the only chance her child has if she raises it on earth, well then that needs to be included in the logline. And the fact that it isn’t included in favor of the vague, “a place she’s only heard rumors about,” indicates to me someone who hasn’t written enough to know how to craft an effective logline. I know every writer hates writing loglines because of this very reason. What do you choose to include or not include? But the thing about loglines is that if you stay in the game long enough, you figure out how to write them effectively, and so when I read a good logline, I know that’s a writer who’s been at this for awhile and knows what they’re doing. In the past, when I see little mistakes like this, I’ve found that the script reflects those mistakes. It has problems as well. And while “Earthbound” may very well be the exception to the rule, I’ve been burned too many times to take a chance on it.

Title: REMOTE

Genre: Sci-fi Drama

Logline: A dysfunctional family’s devoted android confronts the true nature of his role in humanity’s impending demise.

Analysis: This logline starts out okay. But then it becomes waaaaay too general. We go from a “dysfunctional family” (a very contained story) to “humanity’s impeding demise.” Where’s all the stuff in between? Remember, a logline isn’t supposed to tell people the generalities of the story. It’s not a teaser. It’s supposed to tell you the specifics of the story and what’s going to happen. I have no idea what happens in this story (which is the problem) so I can’t accurately fix this logline. But here’s an example of a more specific version: “A dysfunctional family’s devoted android must find and destroy its maker before being updated with the latest software, which will have it turn on and kill its family.” That’s admittedly a dumb idea but do you see how specificity in the plot explanation creates a clearer movie than “confronts the true nature of his role in humanity’s impending demise?” There are actual specific tasks being alluded to, something the reader can visualize.

Obviously, subjectivity plays a role in picking loglines. So my analysis here should not be seen as the end all be all. But this is a pretty accurate breakdown of how your loglines will be received. Do some market research BEFORE you write a script. Send your friends five loglines and ask them to rank them 1-5. What happens when you’ve spent 6 months on a script is that you become emotionally attached to the idea and can’t see it clearly. Whereas when you’re still in the idea stage and several people tell you the idea isn’t good, it’s easier to let it go.

Curious to see what you guys thought of these loglines. Did I overlook any?

Are you sending your screenplay out into the world without getting professional feedback? That is dangerous, my friend. I can tell you exactly what they’re going to criticize you for and help you fix those problems ahead of time. I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “CONSULTATION” if you’re interested. Chat soon!

The Brigands of Rattleborge meets Water for Elephants meets Deliverance?

Genre: Drama/Dark/Thriller

Premise: After a 1976 traveling carnival sets up in a small town in Louisiana, the locals become enraged with the actions of the carnival workers, and set about taking the carnival down.

About: S. Craig Zahler needs no introduction on this site. He is the writer of The Brigands of Rattleborge, one of my top 5 scripts (and soon to become a TV show). Fury of the Strongman is a script that he’s been pushing for quite a while and, according to the trusty source, “the internet,” he’s still actively trying to get it made. I hope he succeeds! This is probably the most interesting of all his projects.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler

Details: 155 pages

Readability: Slow

No reason to beat around the bush. If you like Zahler, you’re going to love this script. If you hate Zahler, you’re going to detest this script. Since I like Zahler, you probably know where I stand. :)

The year is 1976. A carnival led by a midget named Nickel is enjoying a long stay in a Wisconsin town. Our cast of characters includes Woodburn, the strongman. Laughy, the clown. Wendy, the pretty girl. Young Mountain and Paloma, the husband and wife knife throwing act. Harry the Human Crab (who looks exactly like you’d imagine him to). As well as a host of other oddballs who specialize in unique skills.

Our main focus, though, is Woodburn, who’s furious that his girlfriend, Wendy, wants to do a topless act. Woodburn has seen one too many women from his past go down that route, and when it happens, they keep going, right into prostitution. Despite Wendy’s insistence that she’d never do that, he breaks up with her.

Later that night, a horny teenage couple gets drunk at the carnival then crashes their car into a tree, killing them both. The dead girl happened to be the daughter of the governor, so they get kicked out of Wisconsin. The only place Nickel knows he can go is Louisiana, so they get the caravan together and drive south.

As it so happens, they set up in the very same town Woodburn grew up in, a town that he ran away from the second he was old enough. When he heads into town to get a drink, he’s spotted, and we learn that before he left town, he gave his father a present – he broke his spine, turning him into a paraplegic. People in town like his dad. Which means they don’t like Woodburn.

Meanwhile, Laughy (in full clown makeup) heads into town to get some whisky but is stonewalled by the angry liquor store owner, Right Hook Ronnie. Ronnie thinks that Laughy is black under that makeup and he doesn’t sell liquor to black people. Laughy refuses to leave until he gets his whisky and things get heated, resulting in Laughy pulling a gun on Ronnie. This ensures that Laughy wins this round. But Ronnie assures him that this fight isn’t over.

Ronnie then gets all the town degenerates together and heads to that night’s show. At first, all they do is heckle. But then they start spreading out, beating up carnival workers in the shadows. And when they find Wendy’s tent, let’s just say things go as bad as they can possibly go. It doesn’t take long for Woodburn to figure out who was responsible for Wendy’s death, and when he does, every single man involved will have to answer to the fury… of the strongman.

Fury of the Strongman is vintage S. Craig Zahler.

A man is wronged. That man wants revenge. And nothing is going to stand in his way.

I’ve tried, over the years, to figure out Zahler’s formula – why his scripts hit harder than others, and there are a couple of things that stand out.

One, he takes his time in the first act to really set up his characters. A lot of writers rush through this part. They’re scared of people like me saying they’re taking too long. Zahler doesn’t care. He makes sure to give every character a proper description (“Lying there upon a bench that is comprised of raw wood and cinder blocks and holding a barbell with two rigid fists is CHAD WOODBURN, a shirtless thirty-nine year-old in jeans who has receding copper-brown hair and the massive muscular physique of a champion weight-lifter. A GRUNT and a thick EXHALATION issue from his mouth as he pushes three hundred and fifty pounds off of his chest and into the air.”)

He then follows that description with an introductory scene that solidifies who the character is. Here, we meet Woodburn breaking up with his girlfriend because he doesn’t agree with her choice to do a topless act. We now have a very good feel for who this character is. The reason that’s important is because the better we know a character, the more we care. I can’t stress this enough. The newer screenwriters always screw this up. They always write vague characters. Maybe Zahler goes too far and gets too specific. But it’s better to know too much about a character than too little.

What’s amazing about Zahler is that he doesn’t just do this for one character. He does it for ten characters. And he doesn’t compromise. Everyone gets a full description. Everyone gets a full scene that solidifies who they are.

Another thing Zahler does is he’ll include two inciting incidents. He has the early inciting incident that jump starts the movie. And then he has the ‘official’ inciting incident that turns the script from a slow-burn into a full-on thriller. The early inciting incident in “Fury” is the teenaged couple crashing the car and dying. That INCITES the local authorities to kick the carnival out of town, which forces them to set up in another state.

The second (official) inciting incident is when Laughy gets in a fight with a local liquor store owner. After Laughy pulls a gun on him, the owner, Right Hook Ronnie, vows revenge. He rounds up all the scum and heads to the carnival that night to cause trouble. This doesn’t happen until page 70 (!!!), by the way, which is halfway through the script.

Once Zahler gets his two inciting incidents out of the way, the revenge storyline kicks in. From there, it’s all about intense blood and violence. This section of the script isn’t just meant to serve the story, it’s meant to leave an impression on the reader, which is why I think a lot of people can’t handle Zahler. He goes “all in” on his violent scenes.

The weird thing about this script is that it’s very similar to The Brigands of Rattleborge. So similar that if I would’ve read this instead of Rattleborge in 2009, it probably would’ve been the script that I gave an [x] impressive to and placed in my Top 10. But these ultra-violent scripts play differently in 2021 compared to 2009. Something about what’s happened in the world since that time – all the movements, all the craziness – makes what happens in this script feel a little *too* real.

So I found myself wincing more during Fury than I would’ve in the past. Also, I think there’s something to be said about creativity in violence that makes it a little more palatable. That’s what I remember from The Brigands of Rattleborge. There’s that famous scene where our anti-hero cuts a hole in a guy’s body then sends a hamster inside of it to wreak havoc. It was kind of fun in a gross way. Whereas here, we just get brute violence. At least that’s how it felt. Maybe I’m becoming a wimp as I get older.

Despite this, it’s impossible not to be drawn into this story. In a world where we get the same movies packaged in slightly different containers over and over again, “Fury” feels like an original. I’m surprised this hasn’t been more of a priority in Zahler’s extensive screenplay slate. It feels like nothing else out there right now. And it certainly leaves an impression.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Place characters in situations where they’re not welcome. I know this seems obvious. But it’s one of the easiest ways to generate conflict. When Laughy walks into the liquor store, he’s not welcome there. When Woodburn shows up at the local bar, he’s not welcome there. ‘Not welcome’ means CONFLICT and conflict is the key to entertaining audiences. Any time you’re searching for a scene to jumpstart your story, send your characters into a situation where they’re not welcome.