I review a big high concept sale. I come up with a great twist ending for the movie that’s better than anything they’ll come up with. I tell you all about who Chris Dennis and I are targeting for his contest-winning script, “Kinetic” and how we plan to do it. I, of course, rant about Star Wars cause I can’t help myself. I give you my Wandavision thoughts. And I take you around town to look at the latest projects being sold. This newsletter will make your weekend complete!

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

A reader e-mailed me yesterday and asked a good question: Do you write a logline before you write the script or do you only write it afterwards? The question stemmed from an idea that “Save The Cat’s” Blake Snyder promoted, which is that he would never write a script until he had the logline figured out.

The reason he gave for this proclamation is that unless you can conceptualize your screenplay in a single sentence, then the idea doesn’t work as a movie. His theory boiled down to good movies have a “point.” They have a “goal.” And as long as you have one of those two things, you should be able to convey it in one sentence.

Parasite is about a poor family that tries to take over a rich family’s home. Invisible Man is about a woman trying to take down her abusive dead boyfriend. Knives Out is about solving a murder. Tenet is about… oooooh, wait a minute. We may have something to discuss here.

What is Tenet about? Tenet is a movie you cannot summarize well in a logline. Is it a coincidence, then, that the movie is unwieldy and difficult to understand? There’s no way to prove it for sure but I just shook my magic 8-ball and it came up with “Signs point to yes.” Christopher Nolan would probably shoot us for saying so but had he sat down and distilled his concept into a logline, he may have discovered its weaknesses and changed some elements around until Tenet became stronger.

One of the biggest enemies of screenwriting is vagueness. Wherever there’s vagueness, there is a story unsure of where to go. So if you’re vague before you’ve written your script, there’s a good chance portions of the script itself are going to be vague. Now in a logline, those portions may amount to a word or two. But in a screenplay, they may amount to 10 to 25 pages at a time.

Let’s take this further and think of a good movie that covers a lot of ground and therefore, theoretically, shouldn’t be able to fit into a single logline. Can The Godfather be summarized in a logline? I did a google search and found this: “The aging patriarch of an organized crime dynasty transfers control of his clandestine empire to his reluctant son.”

This would seem to say “no.” It’s too vague and doesn’t convey any direction in the story. But I’ll give you a logline tip. Always try and write the logline from the point of view of the character driving the story (which is almost always the hero).

Therefore we’d get something like this: “A reluctant son is forced to take over his father’s organized crime dynasty while fending off the other mob families in town who are determined to eliminate his family for good.” This clearly conveys what The Godfather is about without any trickery or vagueness. So I say it passes Blake Snyder’s logline test.

Let’s challenge ourselves further, though. What about Joker? That’s a good movie. But, on first glance, it wouldn’t pass the Blake Snyder logline test. There isn’t a clear goal in the movie. I’m not even sure there’s a clear point. It’s more about a man’s descent into madness and the things that come about due to that madness. It’s also sort of a “divided in two” movie where the first half of the film is about Arthur Fleck trying to make a living as a comedian and the second half is about him fighting back against the city and losing his mind. It’s not easy to write a logline where the direction of the film changes midway through.

We’re getting into a complicated area here that necessitates a nuanced discussion. But, generally speaking, character pieces are harder to confine to a logline because the journey happens inside the character as opposed to outside. And that never reads well in logline form. “A man with mental health problems attempts to deal with his demons in an increasingly violent New York City while trying to become a stand up comedian.” It’s okay. But notice the main thrust of the logline is “deals with his demons.” That’s an internal battle. The logline still lacks plot clarity, which, 99% of the time, means the script is going to wander. It just so happens that Todd Phillips is aware of this pitfall and made sure to troubleshoot it so that the script still worked.

Which is to say, YES, it’s possible to write a good script without having a good logline, but there are mitigating factors. It’s usually a character piece. The writer inherently understands the weakness of his narrative and gameplans a way to counter that weakness.

The writers who I deal with aren’t even aware that there’s a pitfall in their concept in the first place so, of course, they can’t troubleshoot it. Which results in a messy unfocused screenplay.

Which is a long way of me saying, “Yes, you should try to write a logline BEFORE you write your script. Because not only does doing so force you to learn what your script is really about (distilling anything down to its essence will achieve this). But you may be able to identify holes in the story that you wouldn’t have otherwise noticed.

I received a logline recently that went something like this (I’m going to change some things around to protect the writer’s idea): “An older woman gets a call that the baby who was taken from her 30 years ago wants to meet her.” At first glance, this logline sounds like a movie. There’s definitely something interesting about your baby being stolen from you and never meeting them until they’re an adult. But where is the story? Or, a clearer way to put it: “And then what?” Does her daughter show up, say how much she missed her, and then leave? Where does the movie go? Cause all that you’ve given me is the first act.

Here’s a better logline. I’m writing this literally off the top of my head so I’ll be the first to admit it’s not perfect. But it’s an example of how figuring out the logline can help you discover what your movie is really about. “After an older woman is reunited with her daughter, who was stolen from her 30 years ago as a baby, she begins to suspect that the visitor is not who she says she is, and that her ultimate plan is to harm her.”

Let me reiterate. Not a movie that’s going to be made any time soon. But you can see more of a movie in this version than the previous version. We get the “and then what” part of the story that was missing from the initial logline. Too many writers start writing their screenplays without figuring out the “and then what” part. So when they get to that moment in the screenplay, it’s no coincidence why they run out of ideas.

Now, to answer the original writer’s question, just because you’re basing your movie on the logline you wrote ahead of time, that doesn’t mean you won’t discover a better movie along the way. And, if that happens, you should go back to your logline and write it again. And if your story improves again while you’re writing it, go change your logline again. And when you’re finally done, you’ll write the big final logline that reflects what the script became. This will be the logline you send out to people.

I know lots of screenwriters think loglines are evil. But they can help you write a good movie if you let them. The more vagaries your concept includes, the more you should turn to your logline as a way to figure out the script’s problems.

So go forth and write those loglines, my friends! And if you’re having trouble, I offer two services that can help. One is a quick-and-dirty rating and analysis of your logline that goes for $25. The other is a more involved process where we can e-mail back and forth, collectively working on your logline until we get it right. That’s $40. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “logline help.”

Genre: Comedy/Drama/Thriller?

Premise: (from Black List) Ready for a night of partying, a group of Black and Latino college students must weigh the pros and cons of calling the police when faced with an emergency

About: This script finished in the top 15 of last year’s Black List. It started off as a short film, which helped the writer, K.D. Davila, sell it to Netflix.

Writer: K.D. Davila

Details: 120 pages

Being so busy this week, I find myself even more focused on a script’s page length than usual. If I see 120 pages when I open a script, I am taking a deep breath, then spending the next 120 seconds trying not to yell at my screen.

But let’s say your script is going to be long and there’s nothing you can do about that. Are you screwed? No, you are not. You can still save yourself by making the script EASY TO READ. That means paragraphs that are 3 lines or less. That means sharp concise sentences. It means a commitment to making the eyes move down the page as fast as possible.

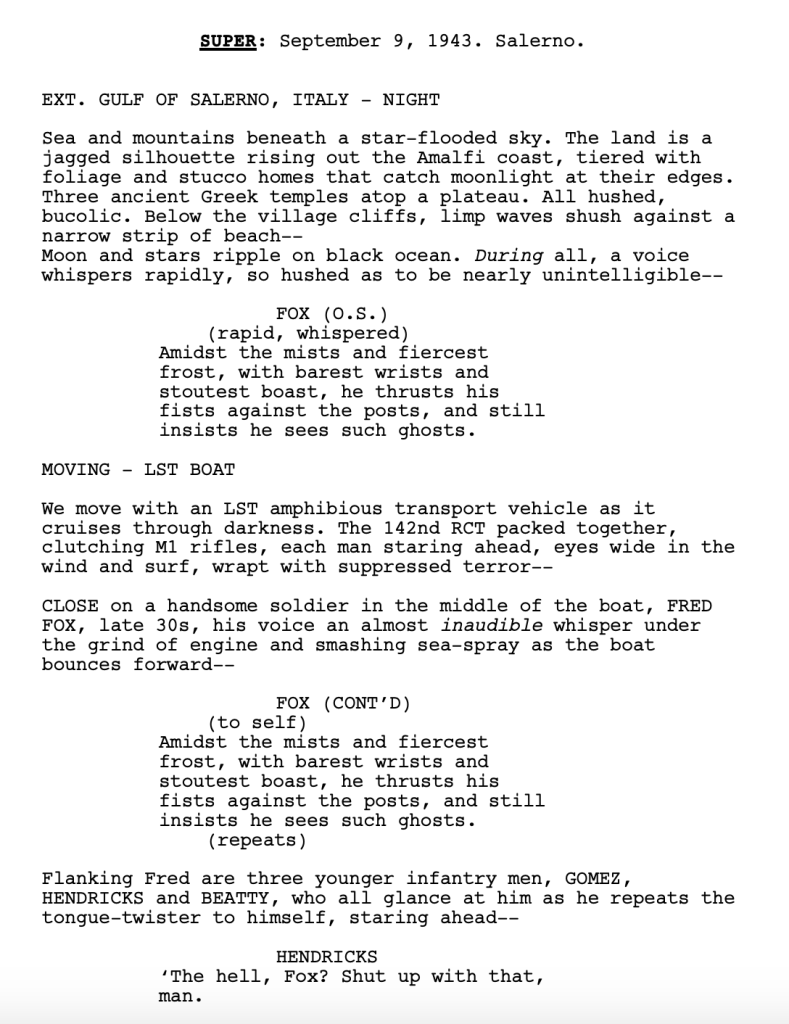

But if you violate BOTH of these principles? If your script is 120+ pages AND it’s written in a big slow chunky manner? Prepare for a reader’s wrath. The other day I was going to review Ghost Army, the Ben Affleck project about deception tactics in World War 2. The page count was 120. And the first page? Well, I’ll let you see it for yourselves:

Is there any other script in history that wants to be hated more by readers than this one?

I bring this up because Emergency is 120 pages but when I opened it, I saw that the writing was sparse and clean. So I knew it wasn’t going to be a slog. Well, I knew it wouldn’t be a slog on the *writing* end. As for the *story* side of the equation, let’s find out together.

Our story is set at the fictional Buchanan University, a woke white college with only a few minority students. Two of those minorities are Kunle, a black 21 year old who comes from a family of doctors, and Sean, a black 21 year old who comes from a low-income neighborhood. The two are best friends and roommates.

On their way to an epic night out, Sean and Kunle come home to find an unconscious white girl in their room. Naturally, the two freak out, not only because there’s a potentially dead person in their place but because it does not look good if there’s an incapacitated white girl in two black men’s apartment.

Luckily, the girl wakes up. But she can barely speak. After an argument about whether to call the police or not, the two decide instead to bring the girl to the hospital. They recruit their buddy, Carlos, throw the girl in the car, and off they go.

Halfway there, they come across a frat party and figure the girl’s night must have originated there. Sean has the idea to leave the girl at the party, which Kunle things is the dumbest idea ever. After another argument, they decide to stick to their original plan of getting her to the hospital.

Meanwhile, we cut to drunk girl’s sister, Maddy, who’s looking for Drunky. It’s here where we learn that Maddy’s sister is still in high school! Meaning Sean and Kunle are going to look even worse if they’re caught with this girl.

We follow the two groups around town as Maddy gets closer and closer to locating her sister. When they finally collide, Maddy takes the reins to get her sister to the hospital, with Kunle in tow. Halfway there, the drunk sister goes into cardiac arrest, forcing Kunle to perform CPR. Also, right at that moment, a cop car chirps behind them, forcing the car to a stop. The cops then move in, and we get a big climactic confrontation that may result in someone losing their life. But who will it be???

“Emergency” is a hard to describe script. It’s Weekend at Bernie’s meets Harold and Kumar meets Crash meets… The Hangover, maybe? If that sounds like an impossible combo, that is my thought as well. The tone here is very hard to get a handle on.

The final scene is a good example of this. Here we have this girl dying and this guy giving her CPR, and in order to keep the CPR rhythm, he’s singing to himself, “Staying Alive” (a commonly suggested tune to hum when you’re giving CPR, as it mirrors the compression rhythm). I suppose there’s a way to shoot this where it sounds more tragic than humorous. But to me it just felt goofy.

The script very much has a “Weekend at Bernie’s” vibe to it. They’re dragging this mumbling girl around just like Bernie was dragged around. And yet it intermittently takes on serious subject matter. There will be intense discussions about racism, for example. So the thought in the back of my head the whole time I was reading this was, “What is this movie?” I could never wrap my brain around it.

But the script does have some high points. There’s a nice conflict at the heart of Sean and Kunle’s friendship. Kunle is privileged. Sam is not. That creates tension in their relationship. A good screenplay will do exactly this. The writer will figure out, via backstory, where the problems are in a relationship so that when the shit hits the fan and those characters are stressed, you have conflict ready to go between the two. It doesn’t need to be manufactured on the spot.

And despite my critique of the “Staying Alive” moment, the last scene of the movie is intense. I know that because I was on the edge of my seat saying, “Is somebody about to get killed here??” My guess is that this scene was the focus of the short film that inspired this script. Because it’s clearly the most thought-out scene in the screenplay.

I wouldn’t say everything else in the script was filler. But little else was necessary. The stakes were never high enough for us to care what happened over the first two acts. I kept thinking to myself, “What’s the worst that can happen here? The girl’s sister finds them, Sean and Kunle give the drunk girl back, the end.”

Instead, the sister finds them, keeps her distance, calls the cops, the cops think she’s racist for assuming that her sister hanging out with black guys means they’re kidnapping her. So then it’s back to the sister following them around some more.

A story has to evolve. It can’t keep hitting the same beats the whole way through. Last year’s Oscar winner, Parasite, keeps evolving its story. Every 15 pages something new happens that changes the story (a new family member enters the house, a secret basement is discovered). Driving around in circles is not evolving the story.

“Emergency” is one great scene and a script in search of justifying everything that comes before it. With higher stakes and a tighter grip on its tone, I probably would’ve recommended this one.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the ways I can spot a weak script is if there’s a character who’s getting a lot of screen time that I know nothing about. And the reason I know nothing about them is because the writer hasn’t done the work to figure the character out and understand why they’re in the story. Carlos is one of the main characters here. He gets pulled into this with his roommates, Sean and Kunle. But he barely says anything and he barely does anything of note. If you’re going to give a character more than six scenes, they need to have some depth, some arc. Or else, you probably want to drop the character.

What does a producer do anyway? Maybe today’s post will give you an idea.

Today’s post is an informal continuation of yesterday’s contest winner announcement. So if you haven’t read that post, check it out.

Today, I thought I’d share a little of my producing journey with you in the hopes that you gain some perspective on what happens with a screenplay once it’s hurled into the system.

When you’re a producer with a script and you’re trying to make a movie, your end goal is basically one thing: find financing. Cause you can’t make a movie without money. So the question becomes, how do you get that money? And this is where things get tricky because there are a lot of paths you can take to get to that point.

Unfortunately, you cannot get financing based on your script alone. I’m sure it’s happened before. But there’s not enough meat there for people to invest in. That doesn’t mean a script is worthless. Quite the opposite. A good script with a bankable premise is what ATTRACTS the other elements that help get a film financed.

Probably the most common way to do this is to get a bankable actor attached. Once you do that, it’s easier to the get the money because the bank can justify giving money to a project with an actor who has a successful financial performance record.

Another way is to go after a director. The great thing about directors is they’re closer to the “make a movie” finish line than actors. These are the guys who physically make the film. So if David Fincher wants to make your movie, all he has to do is snap his fingers and off you go (unless it’s something with an enormous budget, like World War Z 2).

But both of these angles have limitations. Let’s say you want to get the script to Bradley Cooper (or Bradley Cooper’s people). Sounds like a good plan, right? Get Bradley Cooper involved in your project and it’s a ‘go’ movie. Well, guess what? EVERYONE wants Bradley Cooper to be the star of their movie. So they’re all calling Bradley and pitching their projects. And some of those people pitching are named Todd Phillips. Some of them are named the Russo Brothers. Where do you think you rank on that priority list?

Then you have directors, who bring their own unique challenges to the table. When an actor makes a movie, it may be three months of their life. When a director makes a movie, it’s closer to three years of their life. For that reason, directors tend to be very choosy with their projects. Unlike actors, who can say, “It’s a small time commitment. I can shoot this in less than a month,” directors tend not to attach themselves to something unless they really really love the project.

Why is this relevant? Well, you could spend three months of your life trying to get an A-List director to read your script only for a highly likely (we’re talking 98%) “no.” And, in the meantime, you just lost a ton of momentum.

Now, of course, if an actor or a director needs money, they tend to be a little more lenient in their decision-making process. But those tend to be people who aren’t in demand as much and who wouldn’t move the needle on your project much anyway. So do you really want to go that route?

All of this leads us to the worst thing about making movies: WAITING. The bigger the fish you’re trying to hook, the longer you’re going to wait. Could I get Kinetic in front of Bradley Cooper’s eyes? Probably. Everybody knows everybody in Hollywood so you usually know someone who knows someone close enough that they could get your script to that person. But because it’s not some giant Warner Brothers priority project they’re being sent, who knows when Bradley Cooper (or even his people) are going to read it.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the spectrum, you have actors who are not of Bradley Cooper’s caliber, but who can still get movies made. It’s way easier to get scripts to these people. And since these people aren’t getting the cream-of-the-crop material, when they come across a script that’s actually good, they’re more likely to want to make it.

But therein lies the dilemma. When you go this route, the project you’re making isn’t as sexy. And because it isn’t as sexy, the budget isn’t as high. And because the budget isn’t as high, the production value isn’t going to be as good. Which means the movie’s not going to look as good. Which means you’re probably not going to get that wide release everybody producer dreams of.

BUT! And this is a huge BUT. You got a movie made. Getting a smaller version of your movie made is always better than never making your movie at all.

These are not the only paths either. You could try and sell the script to a studio, in which case the studio would take control over the project and do all this stuff for you. Of course, their version of actor and director are probably going to be different from what you imagined and most likely be based on who the studio has good relationships with. Didn’t imagine Logan Paul as your salt-of-the-earth blue collar trucker lead? Too bad. Someone over at the studio just made a movie with him and wants to keep him in the fold.

Yet another option is to go the agency route. Packaging is what turned agencies into mega-businesses. You set your writer up with an agent at CAA or WME and that agent looks at their full client list and they say, “This movie would be good with Johnny Walters starring and Hans Friedberg directing.” Because those two are under the company umbrella, the lit agent walks over to the talent agent, suggests the idea, which the talent agent loves, and calls can be made to the talent immediately. You could put one of these packages together in the time it takes to fly to London. Well, maybe not London. But Bombay.

But that direction has its drawbacks as well. These big agencies have so much inner-company politics going on that they’re not always doing what’s best for the project. For example, if you’re Relatively New Agent and your writer has a script you think would be great for Christian Bale, your boss may tell you that Senior Agent’s project is getting Christian Bale’s attention right now so you’re not allowed to talk to Christian Bale. But, you know, Paul Bettany is available. You can send the script to him. The agent will then call the writer and, for reasons the writer is totally ignorant about, go on a 20 minute monologue about how great of an actor Paul Bettany is and, oh yeah, maybe you should think about him for the lead.

It may sound like I’m complaining about this but I’m actually not. I just find all the little nooks and crannies of trying to make a movie fascinating. You really have to sit down and strategize to figure out what the best route is. Cause each route has its own unique maze you have to manage your way through.

I also think it’s good for you, the screenwriter, to know this. Once you understand the challenges of getting a project to the finish line, you realize how important it is to come up with a script that a) has a great concept and b) people can’t put down. Cause the best defense for tired people with too much Hollywood bullshit on their mind is a great script. That’s the script that’s most likely to become a movie.

I know this post was a little off-brand but I hope you enjoyed it. :)

KINETIC by Chris Dennis!!!!!

Here’s the logline for Kinetic: “Following a harrowing phone call while out on the road, a long haul trucker with a tormented past must deliver a tank of liquid crystal meth before sundown in order to save his pregnant wife.”

If you missed it, you can see all five finalist loglines here.

To be honest, today’s winner was a difficult call. Crescent City, Mother Redeemer, and Kinetic were neck and neck all weekend as I tried to decide who the winner was. The argument for Crescent City was its deep interesting mythology, its modern lead character, its enormous potential as a franchise, and it being the highest concept of the bunch. The argument for Mother Redeemer was that it had the best character development, the lowest budget, and has an amazing third act. Mark my words, when this movie gets made, the line “I’m the Mother Redeemer, motherf#cker,” will be one of the most quoted lines of the year.

In the end, the reason Kinetic edged out the others is that it knew exactly what it wanted to be and gives the audience exactly what they want. This is a good old fashioned action movie. It’s about a dude in a truck who some bad people decide to f*ck with and in the process they unleash the kraken. There’s no other script in the top 5 that has a clearer poster or trailer than Kinetic.

It’s The Equalizer. It’s John Wick. It’s Taken. But wrapped in this dirty messy rural universe. Clay, the main character, feels like a descendent of the cowboys from those old Clint Eastwood movies. And the trucker angle is just unique enough to set this movie apart from its influences. This is the blue collar version of Taken. And I have no doubt there’s a huge audience for that.

On top of all that, I see franchise potential. This main character is such a badass that he could carry three or four more Kinetic movies if we want. That factored into the win as well. Because like I told you guys from the very beginning of this contest. I wanted to find MOVIES. Not scripts. MOVIES. And this is the most movie script of all 2000 entries I received.

There’s one more thing that pushed Kinetic over the edge. The main character, Clay, is surprisingly deep for an action movie hero. Chris Dennis, the writer, explains what he was thinking when he conceived of the character:

“Clay isn’t your typical one-dimensional hero seen in this sort of script. He’s broken. He’s unsure of himself. He’s planned out this life with his wife but he’s not sold on it. Only when he realizes that he’s about to lose it all does he steel himself to recover it at all costs. There’s been mention of the cocaine scene in the truck, the one where Clay is forced by his captor to snort it off the steering wheel. The cocaine isn’t his ‘Popeye spinach’… no. It’s symbolic of this life he’s worked desperately to put behind him. The hurt, the loss, the pain of everything he’s experienced encapsulated in that thin white line. And when that asshole puts a gun to his head and forces him to partake, Clay sees that life he’s built starting to crumble, and realizes that the only way out is if he takes matters into his own hands. It’s devastating for him in the moment, but if he doesn’t act, what follows will be even more heartbreaking!”

If you’re wondering how Chris wrote such a great script, his story should be inspiring to all of you. It’s basically what I’ve been telling you guys all along. Keep writing, keep reading, and keep learning. You do that long enough, you’re going to write something great. Here’s Chris on how he got to this point:

“For a brief time I thought I wanted to direct films, even went to school for it, but as I became more aware of the movie making process, I was instinctively drawn to how films looked on the page, which led me to buying Syd Fields’ classic, “Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting.” From there, I started to track down the screenplays of my favorite movies to read and compare them with how they looked on the screen, which helped me understand how the written word is translated visually (I also read a certain spectacular blog! – Carson note: I added the word “spectacular”). I played around with writing screenplays for a bit, wrote some absolutely utter crap, but it was around ’08/’09 that I fully committed to taking writing more seriously, to really try to hone my craft and find my voice. I scheduled time to write; tried to never miss a day unless I absolutely had to. Ever since then I’ve made it a goal to write 2-3 feature length screenplays a year – some years it’s easy, others it feels like a monumental task (and that was in pre-pandemic times!).

“A lot of people pause when I tell them I’ve been at this for over a decade now without ‘breaking in.’ Sure, it’s a loooooooong time, I know, but I keep going because deep down I love screenwriting. It satisfies some strange desire in me, and I figure if I love it enough to do it for free, it’ll be that much more fulfilling the moment someone wants to write a check for me to do it. Plus I’m an optimist… I just know my next script is going to be my best. I won’t say the journey’s been easy… not at all. The entire time I’ve been writing I’ve had to juggle a ton of obligations, ranging from full-time jobs to being a husband and a father to 3 kids under the age of ten. But I still find time to write. I wake up at 3 am before the rest of my day starts to write. I stay up late on the weekends to write. And much to the chagrin of my wife, I often skip out on non-essential family functions to write. Why? Because I love it, and because deep down I know that I still need to hone my craft.

“Though I’ve yet to ‘break in,’ I have some modest success in contests along the way, which keeps signaling to me that I’m on the right path. I’m a 3-time Page Awards winner (Grand Prize shy of the Grand Slam), a 3-time Launch Pad Feature Finalist, WeScreenplay Feature winner, along with high placements in several other contests. Now I can add another to this list — THE LAST GREAT SCREENPLAY CONTEST!!!!!!!!!!”

I also asked Chris what inspired him to write Kinetic specifically:

“The seed of the idea came to me while driving and listening to the song “Thinking On A Woman,” by Colter Wall. The song is kind of a lamentation on the tragic side of long-haul trucking… about missed time, lost love, and the vices a man turns to in order to ease his troubled mind. I had been on the search for an idea that was somewhat contained, so I took the character of this song and flipped his situation. What if he’s overcome his demons? They’re there, sure, but he’s managing to keep them at bay. And what if he’s on his last haul, heading home to a pregnant wife to leave this lonely life on the road for good? But what if that happy life he’s heading home to is suddenly put into jeopardy? What lengths would this man go to in order to preserve that little slice of heaven that he’s built?

So with that as my jumping off point, I molded this truck driving character, Clay Cutler, as a disgraced Special Forces veteran and a recovering addict, who’s nearly got his life back in order when the shit hits the fan and he has to overcome obstacle after obstacle to get that life back. I set out to write an old school action flick with no filler, semi-contained (pun intended), with one hero and one goal: to get his wife and unborn child back, no matter what it takes. And once Clay makes that decision, there’s nothing that’s going to stop him.”

As I’m reading back Chris’s answers, I’m reminded of something else I loved about the script – the recklessness of both the story and its hero. I’ve been reading a lot of screenplays lately where the writers let up on the gas, which leaves the script feeling neutered. Kinetic, true to its title, barrels forward in a way that other writers are scared to do. It’s almost like they’re afraid they’ll be unable to keep it up til the last page. Kinetic is this don’t-stop-til-the-last-credit-rolls force of nature. It really wants to deliver on its promise for a great fun action movie. And it does that.

So what’s next for Kinetic, Chris, and myself?

GETTING THIS MOVIE MADE, BABY!

I’ve just started talking to close contacts about Kinetic. I’m trying to find out which production houses want to make a movie like this. I’m going to be coming after Original Film (Fast and Furious guys). I’m going to be coming after 87Eleven (Stahelski and Leitch’s company). G-Base (Gerard Butler’s company) is going to get a call. Atlas Entertainment. Village Roadshow. Thunder Road. Millenium.

And hey, if you’re a production house that makes movies like Kinetic and you’re reading this post right now, E-MAIL ME (carsonreeves1@gmail.com). I’ll jump on Zoom with you tomorrow and if we click, we’ll set this up somewhere by the end of the week! I see this as a slam dunk. It’s not a matter of if it will get made. It’s a matter of who makes it with us.

Congratulations to Chris Dennis one more time. By this time next year I hope we’ll be sharing with you all the crazy stories from the set. :)

WANT YOUR OWN SCRIPTSHADOW GLORY? – This is a reminder that the next Amateur Showdown (High Concept Showdown – where only high concept scripts can compete) is coming in March! So get those scripts ready! If you don’t know what a high concept is, check out this post here…

Amateur Showdown Genre: HIGH CONCEPT

Where: Entries should be sent to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

What: Include title, genre, logline, why you think your script deserves a shot, and a PDF of your script!

Entries Due: Thursday, March 4, 6:00pm Pacific Time