Genre: Comedy

Premise: An action comedy wherein Benji Stone, a lovable but deeply unpopular sixteen year old, is pulled into an international assassination plot by his uncle, a retired undercover assassin charged with babysitting Benji for the weekend.

About: This script finished with 8 votes on this past Black List. The writer, Gabe Delahaye, has written a little bit for TV. Despite having a few feature scripts in development, he doesn’t have a feature credit yet.

Writer: Gabe Delahaye

Details: 115 pages

Err, remember when I said go write a John Wick comedy? I guess I wasn’t paying attention. Somebody already did that. And here it is!

Benji Stone is just a 16 year old Northern suburbs of Chicago dork who likes robotics. The guy’s sole objective is to get into MIT. Well, that’s his sole objective initially. Objectives are about to radically change for Benji in about 24 hours. But, meanwhile, he and his best friend, the super popular Lakshmi, need to decide if they’re going to a party tonight.

That decision is made for Benji, though, since his mom is going out of town and his uncle, Gideon, will be staying for the week, babysitting him. It turns out Gideon is kind of a nightmare. His questionable fashion choices (he wears a baby blue “Frozen” hat) are usurped only by his complete lack of humanity. The guy has the social graces of a Buckingham Palace guard.

Gideon makes Benji take him out to eat (Benji picks Denny’s) and that’s Benji’s first clue that something isn’t right here. Gideon drives a $300,000 McLaren. It is at Denny’s where some random guy comes up to their table, tells Gideon he looks like an old friend, and takes a picture of him. This odd moment is followed by Gideon walking into the parking lot and BEATING THE LIVING SHIT OUT OF THE GUY UNTIL HE’S DEAD!

Gideon comes clean to Benji. He’s an international assassin. A retired one. He’s been hiding out for years to convince the world that he’s dead. This was his first step towards trying to live a normal life. And now he’s back on “the board.” And, oh yeah, now that all the assassins know of Benji’s existence, it means that he’s on “the board” as well.

There are not many 16 year olds who can handle being told there’s a million dollar payday on their head and Benji sure isn’t one of them. He begins freaking out. But Gideon assures him that with a little training, he can make him a killer too. Uhhh, Benji says. I DON’T WANT TO BE A KILLER. But it’s too late for that.

Benji tries his best to ignore this horrifying new reality and goes back to school, starting with his driver’s ed test, a test that Gideon insists on joining. It’s a good thing he does. Cause in the middle of it, a group of motorcycle assassins attack them! Gideon leaps into the front seat but is forced to only control the gas and brake while Benji steers their way to a dozen near death crashes.

Benji remains in denial, going to school the next day. But he regrets it when their new “substitute teacher” has quite the strong Eastern European accent. Yes, she’s a killer too! And she attacks Benji! Gideon shows up just in time to take her out. But he informs Benji that the situation is dire. The woman he just killed is the sister of a major crime boss. If she showed up, he won’t be far behind. And this guy is the kind of killer that makes all these other killers look like mannequins. Both Gideon and Benji will be pushed to their limit!

Question #1: Does this pass the comedy concept test?

It does. The comedy concept test is, when you hear the idea, do you automatically think of a bunch of funny scenarios. “Uncle Wick” immediately makes you think of a bunch of funny scenarios. So, right off the bat, it’s looking good.

Question #2: Does this pass the comedy trailer test?

This is kind of like question 1 but it helps you get a better sense of if this is a movie or if it’s just a funny script. Try to imagine the trailer. Does it have a bunch of funny scenarios that will look great in a trailer? This does. The ‘John Wick joins the driver’s test” set piece was genius. Killing your nephew’s substitute teacher in the middle of school is also funny.

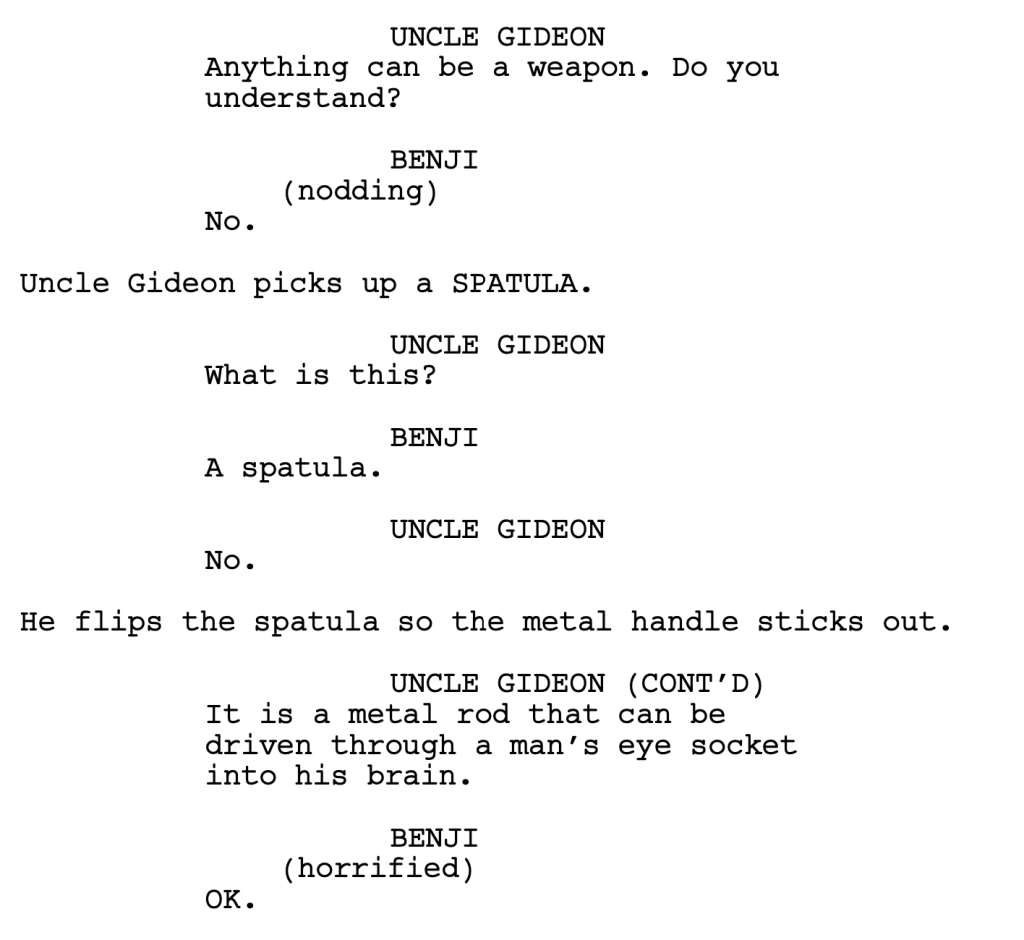

Question #3: Is the dialogue funny?

On this one, Uncle Wick is hit or miss. The dialogue is okay. But I would’ve preferred laughing out loud a lot more. A lot of the dialogue humor is built off of the relationship between Benji and his uncle. It’s Benji going crazy and his Uncle, who’s used to doing this stuff all the time, responding with dozens of variations of “What’s the big deal?” And these moments *are* funny. But I was hoping for some more wordplay. Funnier phrasing. Some more clever back-and-forth. It kind of kept hitting that same beat the whole time.

The script’s biggest weakness is that all the focus is put on Ben and the Uncle’s storyline – which is where the focus should be. That’s the concept. But it’s clear that Delahaye didn’t put nearly as much thought into Ben’s life. For example, Ben is described as the biggest nerd in school. Then, two pages later, we introduce his best friend, a girl who is the most popular girl in school.

Uhhhh, what????

We’re just expected to go with that? Um, no. That’s the kind of friendship that needs more explanation. And this continued throughout the school stuff. It was all rather thin. The bully had the lamest bully lines ever. Ben was trying to get the hottest girl in school to go to the dance with him.

It’s not that these things shouldn’t be used. They are high school movie staples. But they only work when you twist them slightly. So they feel a little unique. That uniqueness is what sets your high school script apart from everyone else’s.

Another issue with the script is the structure. Typically, in these movies, you go out on an adventure. A good example is The Spy Who Dumped Me. That movie sends its protagonists off on an adventure. And whenever your characters are on the move, it’s easier to structure, because the objectives are always destinations, and you can double those destinations up as major plot beats.

Here, they stay in town. And that presents challenges, which we see rearing their ugly head later in the script. For example, once we’ve established that there’s a million dollar price tag on Benji’s head, why is he going to school?

Clearly, the reason he’s going to school is so the writer can get in his Substitute Teacher Fight Set Piece. Which is great for them, but lazy for the storytelling. We needed a clearer time frame and goal for our heroes. Otherwise, you get your heroes waiting around for the bad guys to show up, and EVERYONE HERE knows how much I hate ‘waiting around’ plots. They cause way more trouble than they’re worth. You want your heroes to be active and driving the plot, not the other way around.

In the end, there’s enough juice in this comedy bottle to make it worth drinking. It’s not perfect but it was a welcome upgrade from the script that I started to read for today’s review – Black Mitzvah. Oy vey. Do NOT read that if you want to laugh.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: DRESSING UP DIALOGUE – You are writing a comedy, correct? So it doesn’t make sense for your characters to say things in a straightforward manner (unless that’s the kind of character they are). Early in the script, Benji’s friend knows something about Benji’s crush that can help him get her. So she tells him that. Now before I give you the sentence she uses to convey that, I want you to write your own version of what she says. Because, what you’re trying not to do is something like this: “Hey, I heard something about Heather that can help you.” That line is fine in a drama. But this is a comedy. So how can you dress that line up? Here’s what the friend actually says to Benji: “Speaking of something weighing on your conscience, if I give you a piece of Heather intel, promise not to let the police know I helped you plan her murder?” So much more creative. It’s not laugh out loud funny. But it gets a giggle. And that’s how you want to be thinking when you write your comedy dialogue lines. Dress them up.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: An Air Marshal transporting a fugitive across the Alaskan wilderness via a small plane finds herself trapped when she suspects their pilot is not who he says he is.

About: Jared Rosenberg has a few scripts in development. But he’s still scratching and clawing his way to his first produced credit. This script finished with 9 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Jared Rosenberg

Details: a slight 93 pages

The contained thriller is BAAAAAAAA-AAACKKKKK.

How come no one here has come up with a contained thriller that takes place in a small plane? The idea was just waiting for you. Then again, that’s usually the effect good ideas have. They arrive with their own personal thought bubble that dances up above your head and wonders, “Why didn’t I think of that?”

BUT!

If you’ve read my contained thriller reviews before, you know what happens to most of these scripts. They don’t have enough meat on the bone. They don’t have enough plot to keep the reader invested.

Tension is everything in these scripts. And when they begin, you get to build that tension. As they reach the second act, you get to hold that tension. But then you start having to answer questions. Then you start having to introduce complications. Things NEED TO HAPPEN to keep our interest. And those things change the dynamics in ways that defuse the tension.

Which means you need to introduce new tension. And that can be challenging for writers. The new tension is never as strong as the old. Figuring out that the guy next to you in the plane is going to kill you – that’s your starting tension. So when you ultimately have to eliminate him as a problem, where is that new tension going to come from? The good writers figure it out. The bad writers either don’t figure it out or they replace it with lame generic tension.

Let’s find out where Rosenberg’s tension landed.

The FBI has tracked Winston all the way out to the middle of Alaska. Winston has good reason to flee. His boss, Moretti, is being tried for lots of criminal acts and Winston was in charge of his books. Moretti’s hearing is tomorrow morning and the FBI has finally got the man who’s going to testify against him by way of U.S. Marshall Madolyn Harris.

Madolyn is just recently getting back on the U.S. Marshall beat after screwing up big time on her last job. Outside of how damn cold it is up here, this job shouldn’t be difficult. She’s got to take Winston on a little Cessna plane over to Anchorage, where they’ll then fly to Washington overnight so Winston can testify against Moretti the next morning.

The pilot who’s flying them is a big gnarly dude named Daryl Booth. After Madolyn handcuffs Winston to his seat, she goes up in front with Daryl. They get up in the air when it’s still daylight and, theoretically, it should only take them 90 minutes.

But we all know it’s not going to be that easy. Almost immediately, Daryl the pilot is acting suspicious. But it’s actually Winston who first notices something is up. A pilot’s ID starts to dribble out from behind Daryl’s seat and it’s Daryl’s pilot’s license… except it’s not Daryl’s face. Which puts Winston in a really sticky situation. He needs to let Madolyn know that Daryl is bad but there’s no easy way to communicate without Daryl hearing.

That’s okay, though, because Madolyn figures it out on her own, and after an intense front seat fight, she’s able to subdue him with her taser. Madolyn then needs Winston’s help to get Daryl to the back where she can handcuff him. But she can’t undo Winston’s restraints because she doesn’t trust him either. But she somehow gets passed-out Daryl to the back and ties him up.

Then Madolyn has a new problem. She has to learn how to fly a plane! She also needs to learn where the hell they are because Daryl sure as hell wasn’t taking them to Anchorage. Madolyn uses her SAT phone to call her office, which only leads to new problems, since she realizes that the only person who could’ve compromised them works in the Marshall’s office. So can she even trust her boss?

And it only gets worse from there. Since Madolyn is so focused on flying the plane, a newly awake Daryl begins his plan of slipping out of these restraints so he can finish the job he was paid for. You begin to wonder if anybody’s going to be make it out of here alive. As Madolyn puts together a last-ditch plan, we pray to the Flight Simulator gods that she’ll figure it out.

I’m happy to report that Flight Risk applies just the right amount of tension turbulence for the running time of its story.

There are a lot of things that work here.

Let me start with the first major plot development. This occurs when Winston finds out that the pilot isn’t who he says he is. When this happened, I knew the script was going to work. Why? Because the more obvious plot point would be for Madolyn to find out first. And that would’ve stolen a good ten pages worth of tension from the story.

Think about it. By having Winston figure it out first, we now have a dramatically ironic situation. Us and Winston know that Daryl is bad. But Madolyn does not. So we’re sitting here screaming at our screen, “HE’S BAD! HE’S A BAD GUY! LISTEN TO WINSTON! HE’S TRYING TO GET YOUR ATTENTION!” You lose that if you start with Madolyn learning Daryl is bad.

It also hints at a way more interesting dynamic, which is that the good guy, Madolyn, is going to have to work with the bad guy, Winston, to survive. I find that to be a more interesting setup than what I was assuming was going to happen, which was that Daryl was working with Winston.

But let’s get to the problem I talked about in the opening of the review. Madolyn subdues Daryl, locking him up in the back seat. You’ve now LOST YOUR INITIAL TENSION. Daryl is still technically a problem since bad guys are always going to try and get out of their restraints. But it’s not nearly as interesting as it was when a free Daryl was right next to Madolyn and we knew he was a killer.

So Rosenberg attacked this problem by introducing a potential inside-job situation with Madolyn’s boss. Her boss is not only the one who, presumably, set her up. But she’s waiting for them in Anchorage. So just by landing in Anchorage, her and Winston are probably going to be offed. Which begs the question, what do they do? They can’t go to Anchorage. And, also, they can’t go anywhere else because Madolyn doesn’t know how to land a plane.

Rosenberg does a good job engaging us with that storyline. I was genuinely worried while I tried to figure out who set them up and what that meant for the three people in this plane.

The only reason why I’m not giving this a higher score is that there’s not anything new here. The execution is great. But if you’ve read these types of scripts before, where you only have a handful of characters, even when you don’t exactly know who’s good and who’s bad, you know enough that nothing’s going to surprise you. And that’s why this doesn’t get some super score. It didn’t shock me.

But it’s still good. And if you’re a contained thriller lover like me, you’re gonna dig this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “A cramped, analog six-seater, powered by a single propeller. Three rows of two seats, including the pilot’s. Roughly the size and layout of your standard minivan.” A huge mistake writers make is setting their movie or major scene inside an area that they do not give any geographic clarity on. I’ve read countless scripts that have taken place inside a spaceship or some period-piece building, where the writer does not inform us how big the setting is and how the location is laid out. This results in what I call, “fuzzy approximation,” whereby the reader is forced to assume what everything looks like themselves. When readers do this, it’s always a fuzzy approximation. As a result, the entire story is fuzzy in their head. Screenplays must do the opposite to be effective. They must be clear and specific. So this simple paragraph at the beginning of Flight Risk telling us exactly what we’re looking at is much appreciated.

Bonus free comedy script idea at the bottom of today’s post if you couldn’t come up with one – Inspired by Kylie Jenner!

Remember, the deadline for Comedy Showdown is… June 17th! (find out how to submit here)

Now, if you’re a well-behaved screenwriter, you did all your homework this week. You wrote down your character bios AND you sketched out your outline. But hey, if you’re one of these ‘fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants’ screenwriters and you didn’t do any of that because you plan on winging it? I’m not going to discriminate. There’s something “in the moment” about comedy that rewards improvisation.

However, starting now, I’m going to hold you to it. Cause we’ve got one week to write our first act. Only one week to write an entire act, Carson?? Are you crazy!? I am crazy, yes. But this isn’t as difficult as it sounds. The perfect comedy script length is 100 pages. That means we can divide our script down into four literal quarters at 25 pages a piece. Your first act, then, is going to be 25 pages. This means that you’ll be writing about 3.5 pages per day.

This also means you’ll be writing roughly two scenes per day (if that makes it any easier). I don’t care if you’re the slowest writer in the world. Two scenes a day is not difficult. You’re not writing a novel where you’re filling up the entire page with text. This is a screenplay. There’s 80% more white background than this is black text. So, come on. Don’t be a baby. You’ve got this.

Now, before we get started, it’s important for me to remind you of the number one killer of written pages: SELF-JUDGEMENT. Think about it. If you never listened to Critical Voice when you were writing, you’d be able to write 50 pages a day. It’s only Critical Voice that stops you. Tells you this isn’t a good enough idea for a scene. This is a dumb character. Brenda would never say that. This scene doesn’t even make sense. This dialogue is awful.

We’re going to re-invite Critical Voice back to the party for the rewrite. But, for your first draft, I need you to send him away. It’s better to accept that there’s going to be a lot of bad writing in this draft and you’re fine with that than it is to let the Critical Voice take over and stop you from finishing your script. So pack up his bags and tell Critical Voice he has to find somewhere else to stay for the next five weeks. Tell him to call Late Night Pizza Order Voice and stay with him. God knows I don’t need that guy around.

Okay, so, we’re trying to meet some key beats in the first act.

1) TEASER – You have to decide if you want a teaser or not. A teaser is basically a scene that is more about hooking the reader than it is establishing a narrative. Teasers are best known for appearing in horror movies. But they can be used in any genre and tend to give the reader a scene that establishes what the feel of the movie will be. For example, a horror film will start off with a scary teaser. An action film will start with an action teaser. And a comedy will start with a funny teaser. A teaser in a comedy probably shouldn’t be more than four pages.

2) CHARACTER SETUP – If you don’t want to do a teaser, you can start straight with character setup. You might say, “Well, Carson, why can’t you just start your comedy with a character setup scene that’s just as funny as if you went with a teaser?” In an ideal world, that’s what you’d do. But what I’ve found is that comedies will often revolve around a grounded hero. And it’s hard to start right off the bat with some crazy scenario that your grounded hero has been thrown into. It’s easier to control the scene and the setting in a way that best sets up the character for the audience. For example, in Meet The Parents, we meet Greg at his nursing job tending to a patient. It’s a mildly funny scene as Greg has to do some uncomfortable stuff to the patient. But it’s more about setting Greg up as this dainty non-masculine presence who won’t be tough enough for his fiance’s big tough father. It’s far from some gut-busting hilarious teaser.

3) THE CHARACTER’S LIFE – After you’ve given us a scene or two to set up your hero, you want to set up other key characters in your story. Sometimes, for example, you’ll be writing American Pie, which follows four different protagonists. So you’ll need this time to set them up too. Once you do that, you want to set up your character’s everyday life. We have to see the normal for the abnormal to have the intended comedic effect. We have to see the hustling bustling 10,000 family member getting-ready mornings in Home Alone for the Kevin being left home all alone in that big house to have the proper effect.

4) SETTING UP THE PLOT – You are also going to be taking this time to set up the plot of your movie. This is the exposition stuff that the reader needs to know in order for the plot to work. This is when you’ll be establishing that there’s a wedding (in The Hangover) and that the guys are going to Vegas for a bachelor party. This shouldn’t be a separate scene from the character setup and character life sequences. It should be woven in with them.

4) INCITING INCIDENT – This is the moment in your story where a major problem will be presented to your hero. This problem is the whole concept of your movie. It’s one of the easiest scenes to write because it’s the whole reason you wanted to write the script in the first place. This is the moment where Kristin Wiig becomes aware that her best friend who’s getting married has a new best friend who will be getting in the way of all her bridesmaids duties. There’s a lot of debate about when the inciting incident should happen. The truth is, it’s different for each movie. Sometimes the inciting incident happens in the very first scene. Sometimes it’s ALREADY HAPPENED, such as in the case of Zombieland, where the zombie problem began before the movie started. In The Hangover, it’s when Doug, the groom, goes missing, which I think doesn’t happen until 25 minutes into the movie, if my memory serves me correctly? So feel this out. But, if you want to go by the book, it usually happens between pages 12-15.

5) THE RESISTANCE – This moment is often referred to as “The Refusal of the Call” and it basically refers to your hero not wanting to deal with the problem. People don’t like change. They don’t like their life upended. So it’s only natural that when some big problem drops into their lap, they resist. And the great thing about comedies is that this section can be really funny. Because it’s funny when somebody is scared to do something or resists something. So have fun with this part, which usually lasts 2-3 scenes.

6) ACCEPTANCE – After resisting all they can, your hero realizes that he has no choice but to go off on the journey. Or maybe he doesn’t realize that and he’s pulled into the journey kicking and screaming, like some of the characters in Jumanji. It’s a comedy so you can fun with this. This scene or group of scenes will be the last sequence in the first act. By the way, when I say “journey,” I don’t always mean literally. There is a literal journey in the hilarious movie, Eurotrip, because the characters, you guessed it, go on a journey through Europe. But sometimes ‘journey’ is symbolic. It could be Mark Wahlberg and Will Ferrell trying to co-exist for the sake of the family in the movie, Daddy’s Home.

Now, don’t worry if your comedy doesn’t fit into this formula. The main beats you want to take care of are setting up your characters and setting up the plot. And then just try to be funny along the way. It’s a comedy so you’re always trying to create scenarios that give you the best opportunity for laughter. And that usually comes from constructing scenes that place your characters in conflict or, at the very least, make them uncomfortable.

In the new movie, “Yes Day,” on Netflix, the writers are tasked with setting up a mother who’s very strict. So they come up with a scene where there’s a parent-teacher conference and the teacher plays a video presentation that the mother’s son made in class, and it’s a video that juxtaposes his mom against a number of famous dictators throughout time. That’s a funnier scene than just having a mom yell at her kid. That’s all you’re trying to do as a comedy writer is be creative and search out the scenes that create the most opportunities for laughs.

25 pages by next Monday.

YOU CAN DO IT!

BONUS COMEDY IDEA FOR ANYBODY WHO WANTS TO USE IT – If you don’t have a comedy idea, here’s one for you, inspired by the recent events with Kylie Jenner setting up a GoFundMe page to pay for surgery for her friend. The surgery costs 60,000 dollars. Kylie Jenner is worth a billion dollars. Yet she sets up a GoFundMe page. Anyway, here’s the idea. It’s titled “GO FUND ME” and it follows a guy who attempts to set up a GoFundMe page for his life, so he doesn’t have to do anything. Have at it!

The “Frank and Beans” scene in There’s Something About Mary is in the argument for funniest movie scene of all time.

And since we’re trying to write a great comedy script of our own, it’s imperative that you study scenes like this.

Let’s start with the basics of comedy. Every good joke needs a setup and a punchline. The way it usually works is that the shorter the amount of time there is between the setup and the punchline, the less funny the joke is. Or, maybe I should say, the less *impactful* the joke is.

The reason for this is obvious. You have less invested in the punchline. Imagine the best knock-knock joke in the world. The most you’ll get out of it is a big laugh. You will never get a long extended laugh out of a knock-knock joke.

That doesn’t mean quick setups and punchlines don’t have their place in comedy. Of course they do. In fact, while you’re setting up your big comedy scenes and set-pieces, you should be using short and medium length setups and punchlines along the way.

With There’s Something About Mary, a big reason the Frank and Beans scene is so funny is that the Farrelly Brothers spent the previous fifteen pages setting the punchline up. Fifteen pages is a lot of screenplay time. It’s one-eighth of your entire movie. So if all you’re doing is setting this scene up in that time, it *better* be a funny scene.

What does set up look like? As I’ve stated here before, “setting up” comedy is about BUILDING UP THE STAKES. Making the stakes as high as you can make them. The higher the stakes are during the scene, the more we’re going to laugh, because it’s important to us that the character succeeds.

Once your stakes are in place, your goal should be to destroy your character. Throw him in the worst situation imaginable. Make it look like it’s impossible for him to succeed. And then keep bombarding him with obstacle after obstacle.

Comedy, probably more than any other genre, requires you to be awful to your main character. Humor comes from struggle. So of course you want to make things bad for your hero. That’s the way to make them struggle. If you’re nice, there’s nothing for them to overcome, and, therefore, less opportunity for funnies.

What’s been Ted’s focus in the first fifteen minutes of the movie? He’s fallen head over heels for this girl from school, Mary. Your first love is a big deal. But the Farrelly Brothers know that the more of a fluke Mary liking Ted is, the higher the stakes will be. Getting a cute girl to go to prom with you is one thing. Getting the most beautiful girl in the world, the kind of girl Ted will never ever have a chance with again ups the stakes dramatically. So the Farrelly Brothers come up with this clever idea that Ted helps out Mary’s mentally disabled brother, which is the main reason she falls for him.

Let me be clear. This scene isn’t one-tenth as funny if Mary is just some cute girl Ted is going to prom with. By shaping all the variables to make this a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Ted, it sets us up for the scene we’re about to watch, where Ted goes into the bathroom, and then, when he zips his pants up, accidentally catches his special parts in the zipper.

The combination of high stakes and “what’s the worst thing you can do to your character right now” are what ignite the series of laughs that follows. What’s the worst thing that can happen? He can’t unzip himself. What’s the next worst? The family learns what’s happened and comes to the door.

Now here’s the thing with a comedy set piece, like this one, which you’ve spent the last fifteen pages setting up. You can KEEP THROWING THINGS AT YOUR CHARACTER to your heart’s desire. You can’t do this scene with a short setup. There’s not enough meat on the joke to keep milking it. But when you’ve set things up as much as the Farrelly Brothers have here, you can KEEP THROWING INCREASINGLY DIFFICULT OBSTACLES at your hero.

So first the dad comes in. Okay, that’s not what Ted wants but at least it’s a guy. But then the mom comes in. Oh god, his prom date’s mom is seeing him in the most vulnerable state he’s ever been in. The Farrelly Brothers smartly realize that, while new people coming in is funny, you have to find jokes in other places as well. So they add this whole segment where the parents aren’t even sure what they’re looking at and need some explanation. After they’re unable to convey to Ted what their question is, the dad makes the analogy, “Are we looking at the frank or the beans?” This then sets off the special needs brother, outside, who starts yelling, “Frank and Beans!” repeatedly.

We’re using a very simple comedy tool here. ESCALATION. We’re making things WORSE and WORSE for your hero. Every time we think it can’t get worse, it does. Now the policeman shows up in the window. Now the fireman shows up. Again, this doesn’t work with just any setup. It only works because we’ve spent 15 minutes setting up this scene.

Another brilliant thing that the Farrelly Brothers do is they don’t show us what’s happened at first. They, instead, show us EVERYBODY’S REACTION to it. Reaction comedy is some of the funniest comedy out there. Watching somebody do something stupid can be humorless until we see the baffled reaction of someone else nearby. So every time somebody looks at Ted’s zipper situation, they’re beyond disgusted. And, every time we see their disgust, we laugh.

Also, like any good comedy writer, you’re not just relying on the setup to do the work. You’re still looking for secondary jokes to occasionally throw in there. One of my favorites happens when the dad brings in the wife and justifies it by saying, “Don’t worry. She’s a dental hygienist. She’ll know exactly what to do.” The line isn’t funny if the dad says, “Don’t worry, she’s a nurse. She’ll know what to do.” It’s the “adjacent profession” aspect of her job that makes the line funny.

That’s another thing about comedy. You have to turn your logic brain off a lot of the time. Your logic brain sets up your plot for you. But some of the funniest lines don’t make complete sense, like this one. What would a dental hygienist know about this situation? You tend to find those lines when you turn the logic off.

Another funny line comes from the policeman: “What’s going on in here? The neighbors said they heard a lady scream.” As if things weren’t humiliating enough with Ted’s literal manhood dangling by a zipper, now he’s being mistaken for a woman.

Another small but funny joke is that the dad isn’t taking the situation as seriously as he should. He thinks it’s kind of funny and begins treating Ted like a prop. “Come here,” the dad says as he grabs Ted. “You gotta see this,” he says to the cop, showing him Ted’s zipper fiasco. This is a subtle but important detail in comedy: Contrast leads to laughs. When someone is in extreme danger and somebody else recognizes that danger and tries every way they can to help them, there’s nothing comedic about that because both characters are on the same wavelength.

But when a character is in danger and another character is casual about it, now you’re going to find comedy because there’s a big contrast between what’s happening and how it’s being responded to.

The Farrelly Brothers do that with another joke as well. What is a cop supposed to do when someone is hurt? They’re supposed to help, right? What’s the first thing this cop says to Ted? “What the hell were you thinking??” There’s a contrast in what he’s supposed to say compared to what he does say. There’s no joke if the cop starts acting really concerned.

In fact, that’s a great way to find jokes. Think about how a character SHOULD ACT and then have them ACT THE OPPOSITE WAY. It doesn’t always work. But when it does, it’s hilarious. The fireman comes in. They show him Ted’s situation. He does not say, “Oh my god. Are you okay?” He just starts laughing at Ted.

A joke that’s kind of interesting here is the mom with the bactine spray. She occasionally sprays Ted’s penis when he’s not looking. I’ve found that these types of jokes don’t work well on the page because they’re “visual gag” jokes. Visual gags can be funny. But they tend to be stuff you find on set. I wouldn’t waste script pages on them. Spend that time trying to come up with lines like, “What the hell were you thinking?”

The scene ends in a funny way as well. The Farrelly’s take all the power away from Ted. This falls in line with the rule: Make things as bad as possible for your character. Ted’s trying to convince them that he’s fine and he can deal with this himself. They ignore him and tell him what they’re going to do to him (unzip it).

So, to summarize. Your set-piece comedy scenes need to be well set up. The more set up you do, the higher the stakes will be. The more we’ll care about the character’s situation. The more engaged we are, the more we’ll laugh. Once you have them in the situation, treat them terribly. Keep throwing obstacles at them. Keep asking, “What’s the worst thing I can do to them in this moment?” In between big jokes, look for clever secondary jokes. You’ll find a lot of jokes through contrast. Also, play with what is expected versus what you actually do to them.

If you follow this blueprint, you too will write a hilarious scene.

And make no mistake, one great comedy scene can make a script. It really can. Because if somebody dies laughing during a big scene of yours, they will want to make your movie, even if the rest of the script isn’t perfect. Because they know they can try to make the rest of the script funny. So there’s a lot of incentive to writing that big hilarious set piece scene.

Good luck!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) A depressed, progressive woman stuck in a conservative small Texas town starts micro-dosing the entire town with marijuana to make them all get along.

About: This script finished with 10 votes on last year’s Black List. Noga Pnueli has written one of my Top 25 scripts – time loop comedy, “Meet Cute.” So I’ve got high expectations today!

Writer: Noga Pnueli

Details: 112 pages

I think the above video best conveys how subjective comedy is. It’s one of the reasons I don’t review a lot of comedy scripts on the site. I always feel like the x-factor of whether I, personally, believe the writer is funny, gets in the way of me being able to accurately assess the script.

A comedy script can be perfectly executed in terms of structure, theme, and character. But if the comedy’s not my cup of tea, I’m still going to hate it. And things get even trickier when you’re trying to assess whether the writer’s not funny to you or not funny period. Because it would be nice if you could definitively say, “Comedy is not your strong suit. You should write in another genre.” But then someone would have to explain to me how people enjoy The Trevor Noah Show and Adam Sandler movies.

The good news is, I *KNOW* today’s writer is funny. She’s got a script in my Top 25 called “Meet Cute,” a time loop rom-com. So I know we’re going to get some mad comedy lessons. At least I hope so. When in doubt, place your faith in Noga Pnueli.

30-something Estee lives in Jacksboro, Texas. Estee is a “lifer.” That means you’re one of these people who gets stuck in the small shitty town you grew up in because you’re too afraid to leave.

But it’s even worse for Estee because she’s the only liberal in town. She works at a bakery where her boss won’t even bake a cake for a gay couple that comes in. This infuriates Estee so much that she gets in an argument with her boss and he fires her.

While stumbling through town hating life, Estee sees that Jacksboro just opened up their first marijuana dispensary. Estee’s never smoked pot in her life so she tries it out and “ohmmmmmmm,” all of a sudden she’s as relaxed and happy as she’s ever been.

So she gets an idea. She makes pot brownies and starts handing them out to people so that they can experience the same things she did. And they do. Which inspires her to make bigger batches of pot brownies. And then pot cookies. And then pot cakes. Which she delivers to everyone. Except, they don’t know they’re all being drugged.

Amazingly, when they figure it out, they’re not mad. They want her to continue low-key dosing them up. You see, as God-fearing Christians, they can’t be seen buying marijuana in town. This way, they get to to get high without the stigma.

When the pot store owner, who kind of has a crush on Estee, realizes what she’s doing, he informs her that he can no longer take part. Which means her entire operation of “Make Town Happy” will fall apart. Which means everyone will be angry and miserable again. Including Estee. So she has to figure out if there’s any last-minute substitute that can provide people with true happiness. What she ends up finding is the last thing she expects.

Initially, I liked High Society. When it comes to comedy, you want a writer who’s actually comedic. I know that sounds obvious. But you can tell a comedic writer by the way they write. For example, here’s an early excerpt from the script….

ESTEE, 30’s, is what is locally referred to as a LIFER, aka a woman who never left her pathetic hometown and whose wasted potential has made a home atop her shoulders like a ton of bricks.

She is currently avoiding her existential woes by baking complicated SOURDOUGH RYE BREAD in her kitchen.

Pay particular attention to that second sentence. Because there are thousands of ways you could’ve written it. You could’ve written, “Estee is currently baking bread.” “A miserable Estee shoves bread dough into her oven.” “Estee kneads the dough for some bread she’s making.”

You get the idea. These sentences convey the same thing Noga wrote. But they do so in a non-comedic manner.

The phrase, “is currently avoiding her existential woes” is a lot more clever, thoughtful, and funny, than simply saying, “is currently baking bread.” The word “complicated” is also relevant here. “Complicated” paints more of a picture for the reader than if the word wasn’t included. It creates a bit more of a comedic edge, particularly when you combine it with the phrase preceding it.

Funny phrasing and word choices, as long as they’re not overused, are a great way to “write funny.”

Unfortunately, despite Noga’s inherent comedic talent, she runs into the most common comedy problem of them all, which is that she doesn’t have a potent enough premise.

Comedic premises can be deceiving. They can seem funny. But a funny logline doesn’t mean you have 100 minutes of funny. It may only mean you have 30 minutes of funny. And the only way to learn this, unfortunately, is to write a handful of crappy comedies. Only through the process of failure do you get a feel for how long a comedic concept can last.

High Society is a 30 minute premise. How do I know this? Because it’s a South Park episode. They have a very similar episode on South Park. And even they struggled to get their concept to the 23 minute mark.

Why doesn’t this concept have legs? Well, we get to the part where everybody is consuming marijuana and chilled out before the midpoint of the script. So, then, what’s left? We’ve already achieved the funny part mentioned in the logline. What now?

The next plot development is: will the town realize they’re being drugged? Is this a funny development? I would argue it isn’t. There is some conflict involved because there are consequences to what Estee has done. So there’s a dramatic reason for us to keep reading. But I wouldn’t say there was any *comedic* reason for us to keep reading. The script isn’t presented in such a way where this reveal will be treated with a laugh.

Then, we finally get that reveal and guess what? Nobody has a problem with Estee doing this. In fact, they all like it. So, ummmmmm, where is the conflict in the movie? Estee literally has zero problems now. She’s drugging people. They like it. Why, exactly, are we still watching this movie? There’s nothing left to be resolved!

Noga seems to realize this so she comes up with this minor conflict whereby the marijuana shop owner says he’s not going to sell her pot anymore. But, at this point, I don’t care. Too much conflict has been sucked out of the story.

If there’s one thing to learn about comedy today, it’s that if you don’t take care of your plot, your comedy won’t matter. If your characters aren’t engaged in some level of compelling conflict that has genuine stakes attached, then we don’t care what happens to your characters. And people won’t laugh if they don’t care what happens to your characters.

I don’t even know what Estee wants in this movie. Why is she even doing any of this? It’s an important question because, if we don’t know, then we don’t know why it’s so important for her to succeed. And without a need to succeed, there are no stakes. The guys in The Hangover cannot, under any circumstances, lose their friend eight hours before his wedding. The stakes are so high that we’re extremely engaged in their mission.

Not so with this one. I get that it’s pot comedy and that this type of comedy is a little more chill. But I’ve seen pot comedies with high stakes and lots of activity (Pineapple Express). So while I’ll give High Society a puff. I’m not giving it a pass.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure that your comedy concept provides stakes that will last 100 minutes. I see too many comedy writers who dive into a comedy script with stakes that get you to page 40. And then they spend the rest of the movie flailing about trying to be funny. This is important, so pay attention. Characters are the most funny when they have something to lose. Therefore, if it’s muddy or unclear what your characters have to lose, chances are, nobody’s laughing. I wasn’t ever clear what Estee had to lose in this movie.