Normally, I say share your movie ideas with as many people as possible. But today I’ll reveal the one movie idea you should guard with your life.

When I spoke with Ravin, the director attached to yesterday’s script, I told him it would be a good idea to post the script so that people could read and learn from it. He and the writer were on the fence about it but ultimately agreed. I bring this up because posting material is big topic among the screenwriting community. Should you post your scripts online or keep them locked up in a virtual vault forever? I wanted to give you a history lesson on why people are so afraid to post their scripts and why they shouldn’t be. I also want to share with you one exception to this rule – the movie idea you should always hold close.

One of the original reasons to keep your script a big secret was because agents made a lot of money selling bad screenplays. Let me explain. The old agent strategy looked something like this: An agent would have a script that nobody had read, they would hype it up over the course of a few days or weeks, they would send the script out to all the studios at once, and then the studios, afraid that they were going to lose out to another studio, would start bidding on the screenplay, which drove the price up, and led to a big sale. Most times, after the excitement had died down, the studio would dive into the script, only to realize it wasn’t very good.

These sort of “trojan horse” sales were driven almost exclusively by buyers not having access to the script prior to the sale. And thus, it was critical, as an aspiring writer trying to get representation, that you be careful about sending your script out. Because if a bunch of people got their hands on your script, it would prevent the agent from being able to use this strategy. If people already knew your script wasn’t very good, you couldn’t trick them. It’s kind of messed up when you think about it. The whole system was designed to sell a bunch of bad screenplays. I still remember a famous agent once saying, “Any agent can sell a good script. Only a real agent can sell a bad one.”

This system was upended when Roy Lee came around and created the first internet tracking board. What happened at these big agencies was that the scripts would get covered by their in-house readers. The tracking board was a way for readers, across the industry, to secretly share with each other the best scripts they’d read. Because of this, bad scripts would get exposed a lot more frequently, which meant agents could no longer send out a script that nobody knew about. This was the first broken link in the chain that argued you should hold your screenplays close to the vest.

6-7 years later, the Black List rolled around. The thing about the Black List was that it provided a new avenue for writers to get noticed. Before, you had to make it through a ton of gatekeepers for your script to be propped up by the industry. With the Black List, you still needed an agent or manager, but you no longer needed one of the top agents or managers. If your script was good, it would be passed around and celebrated on the list. This was the second broken link in the chain because instead of only one person being in charge of whether you became known, it was now multiple people who determined your fate (the Black List voters).

From there, sites like this one, message boards, Reddit, started springing up giving screenwriters more chances than ever to get noticed. The trade-off was that they had to put their script up on the internet. But the pros of that choice were starting to massively outweigh the cons.

There’s no better example of this than Mayhem’s Headhunter script. That script was reviewed here on the site and would go on to be the number one script on The Black List. It used to be that writers would be terrified to have a review and script link up for their script. But what you have to realize is that the odds are so stacked against you getting noticed that one of the only ways to fight those odds is to get your script in front of as many eyeballs as possible and the internet is the only way to do that.

So, to summarize, the number one way to break into the industry in 2001 was to sell a spec script. The number one way to break into the industry in 2021 is to get on the Black List. And the best way to get on the Black List is to blanket the internet with your script to make people aware of it and you. If you don’t do that, how is anybody going to find you? Let’s say you instead have one agent friend you send your scripts to. What if that agent doesn’t like your voice and therefore won’t like anything you write? Are you really going to hinge your entire career on that?

Now, there is another contingent of writers who are terrified of posting their scripts for a different reason – THEFT. When it comes to stealing ideas, it’s a nuanced conversation because having done this for over a decade now, I can tell you that I rarely come across a “great idea” that I haven’t seen before. So most people who think they’ve stumbled upon the holy grail of ideas have stumbled onto an idea someone pitched me last month. In other words, the idea isn’t as “steal-worthy” as they think.

However, there is an argument to be made that if you have a killer idea and you post it on the internet, someone could steal that idea then write their version of it. This is actually the only time I would tell writers not to post their scripts online – if they have an “idea to end all ideas” idea. What kind of idea would that be? Jurassic Park – a modern day dinosaur park with cloned dinosaurs, one of the single greatest movie ideas of all time. Hancock – an alcoholic superhero who doesn’t want to be a superhero. Gemini Man – an old hit man finds himself targeted by a clone of his younger faster self. The Hunger Games – children competing in a to-the-death match with only one winner.

These are ideas that are so highly marketable, they are guaranteed to get made. Therefore, you have to be more careful with them. Because others might see them and think, “Ooh, I could tweak that a little and make it mine” and now you’re competing against others with the same concept. So I understand writers’ reluctance to make these concepts public. But here’s my counter to even that philosophy: Does any of that matter if you die holding onto the greatest movie idea ever conceived? At a certain point, you have to take a risk. You have to tell people about your idea or they’ll never know about it.

Let me quote one of my favorite shows, Survivor. “You can’t trust anyone in this game. They’re all out to get you. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to win without trusting someone.”

What most writers don’t realize is that the chances of someone stealing your idea online and breaking into the industry with it are microscopic compared to you breaking in yourself, pitching your idea around town, and one of *those* people stealing it. That’s because the people inside the industry actually have the power to make movies. Whereas the unknown amateur screenwriter who stole your idea is likely to be a bad writer (based on the fact that they need to steal ideas) and therefore will never make it anywhere. So what are you going to do? Not pitch your ideas to anyone once you become a professional? How are you going to sell anything?

I guess what I’m saying is, the benefits of pushing your ideas out there far outweigh the negatives. We live in a time where there’s so much noise to compete with. For that reason, we can’t afford to carefully and strategically choose three people a year to share our screenplays with. You won’t leave a big enough footprint to create any awareness of your screenwriting existence. My philosophy to become a successful screenwriter is to blanket the internet with your material. The more people who know about your script the better. That is currently THE best way to get noticed.

As we head into the weekend, I’m curious, what you would say are the five best “idea to end all ideas” movie ideas? Remember, we’re not talking about the best movies. Neither Gemini Man or Hancock were very good movies. I’m talking about the best concepts – ideas that, when you heard them, you knew immediately they were a movie.

Is this the best unknown screenplay in Hollywood?

Genre: Drama

Premise: In 1971 Alabama, a poor, gifted, teen living in a trailer with his abusive family is shocked when the prettiest girl in school pays him a visit and asks him if he’ll do her a giant favor.

About: This script was sent to me for a consultation by a director named Ravin Gandhi. The writer, Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder, originally wrote it as a play. She has since adapted it into a screenplay. Wilder has had her plays produced at the Royal Court in London, Alabama Shakespeare Festival, Denver Center, the Hartford Stage, amongst many others. She’s now looking to expand into a screenwriting career. You can learn more about her at her website. By the way, there are a lot of twists and turns in this script. So I encourage you to read it before the review so you’re not spoiled. The link to the script is at the bottom of the review. :)

Writer: Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder

Details: 111 pages

Okay, a little backstory here. Director Ravin Gandhi made his first film a couple of years ago and the biggest lesson he learned, during that process, was how important it was to have a great script. You have a great script, you get better actors. If you have better actors, you get a bigger budget. You have a bigger budget, you get a better team. You get a better team, you get better production value. And, of course, all of those things lead to a bigger and better distribution deal.

So, for his second movie, he made it his number one priority to find a great screenplay. After scouring every corner of the internet and as many agencies that would give him the time of day, the casting director who’d worked on his first film told him she knew a really great playwright who’d written this amazing play. Would he like to take a look?

Ravin said sure with zero expectations, read the play, and was blown away by it. That’s where I came in. He sent it to me, basically wanting to know from the guy who’s read everything, if the script was as good as he thought it was. I hate being put under that kind of pressure because 99 times out of a 100, I have to tell the person, ‘No, it isn’t as good as you think it is.’ But this time, it was.

Spirit of Ecstasy takes place in 1971 Alabama and follows 17 year-old Sammy, a poor shy boy who attends a local private school on scholarship. Unlike almost anyone else in Alabama, Sammy loves to draw, loves to create, loves to explore art. Unfortunately, because he’s poor and likes all these weird things, he doesn’t have any friends.

Sammy lives on a salvage yard in a trailer with his unabashedly “white trash” family. There’s 16 year-old troublemaker Luke, as cool and handsome as Sammy is shy and anxious. There is Lainie, Sammy’s mother, a once optimistic local beauty who’s been relegated to cutting coupons and staring at advertisements for nice neighborhoods she’s never going to live in. And then there’s Lowell, a local football star who’s become a beer-guzzling waste of space.

After Sammy comes home from school one day, we learn that he’s secretly fixing up one of the cars in the junkyard so that, when he’s old enough, he can leave this place. That opportunity may be coming sooner than he thinks. That night, there’s a knock on the door. Lainie goes to answer and is baffled at what she sees standing there – a beautiful girl.

This is Rachel, the most popular girl at Sammy’s school. Lainie isn’t sure what’s more surprising, that someone from the “right side of the tracks” is visiting them or that Sammy knows a girl. She immediately invites Rachel in and begins her southern hospitality routine. Later, once Rachel is able to get Sammy alone, she asks him if he’ll do her a favor and drive her to New Orleans. Sammy doesn’t know what to say.

As dinner rolls around, an increasingly pale-looking Rachel scurries off to the bathroom to throw up and that’s when we learn the true reason why she’s come. She’s pregnant. And she needs to get to New Orleans to get an abortion. She can’t have anybody in town knowing about this, which is why she’s come to the one family nobody cares about.

As Rachel carefully orchestrates the evening so that she can stay the night, she begins to see how abusive Sammy’s family really is. There are things going on behind closed doors that shouldn’t be happening, which only increases the urgency of her and Sammy having to leave.

After giving Sammy the first kiss of his life, she conspires with him to make a run for it before dawn, which Sammy agrees to. But we can’t help but wonder if Rachel’s adoration for Sammy is all just a ruse to get what she needs. Once she’s taken care of her problem, will she ditch him? We may never find out because Lainie discovers their secret plan and goes into nuclear preventative mode to stop her son from leaving her. Pulled between Rachel and his mother, Sammy will have to make the biggest decision of his life. What will he do?

There are soooo many things I liked about this script.

Let’s start with the plot. You guys have heard me go full hater-mode on drama scripts. Writers seem to think that the Drama genre gives them permission to be boring. Look no further than yesterday’s script, Rewired. The Spirit of Ecstasy shows you how to do it right. What’s the big difference? They use a time constraint.

This story doesn’t take place over a summer, a month, or even a week. It takes place in one night. That urgency covers up all of the problems that usually sink drama scripts because we know the issue is going to be resolved within the next 12 hours. That’s how you do drama. It’s the same idea behind 1917. A typical movie about World War 1 in 1917? Nobody cares. But make that story real-time and all of a sudden, “Wow, this is cool.”

That’s initially what pulled me in – just how fast a drama script was moving. I’m not used to that.

Next up, I loved the dramatic question at the center of the story. Dramatic questions are questions you can pose in your script that, if they’re compelling enough, make the reader want to stick around to find out the answer. The dramatic question in Spirit of Ecstasy that hooked me was, “Is Rachel conning Sammy?” Is she pretending to like him because she’s desperate to fix this problem she has? Or does she really like Sammy? Or does she go in planning to con him, but then actually starts to fall for him?

The fact that I was never entirely sure kept me flipping the pages. I had to know if Rachel was honest or not.

From there, the script exhibited an authenticity regarding the time and place that I rarely see. I’ve read scripts about the south in the 70s before. They all fall into the same stereotype traps. From everyone’s super religious to everyone’s a hick to they’re all walking around with guns. This feels different. Sammy is far from your typical southern stereotype. He’s smart and artistic and dances to the beat of his own drum. Even when the characters in Spirit do move towards “stereotype” territory, their actions and dialogue are so specific that it never feels fake or “written.”

By the way, that’s how you avoid cliche. You emphasize specificity. The more specific you can be about a time or place and how people act, that’s what makes your script feel real. The more vague you are, the more cliche you will be. It’s the difference between saying a tennis player “hits a forehand” and a tennis player “slides across the red clay, crushing a forehand down the line, past the outstretched racket of his opponent.”

Which leads us to the biggest star of the script – the dialogue. It’s been a while since I’ve read dialogue this good. The best way for me to identify good dialogue is when I never once am aware of the dialogue. Typically, when I read a script, I can feel the writer’s thought pattern as they’re writing the words of their characters. You sort of see them working out in their head what the characters need to say in the scene.

That never happened once in Spirit of Ecstasy. Every time people spoke, I became lost in their conversations. So much so that I would encourage anyone who wants to be a good dialogue writer to read this script. Because there are so many dialogue lessons you can learn from it.

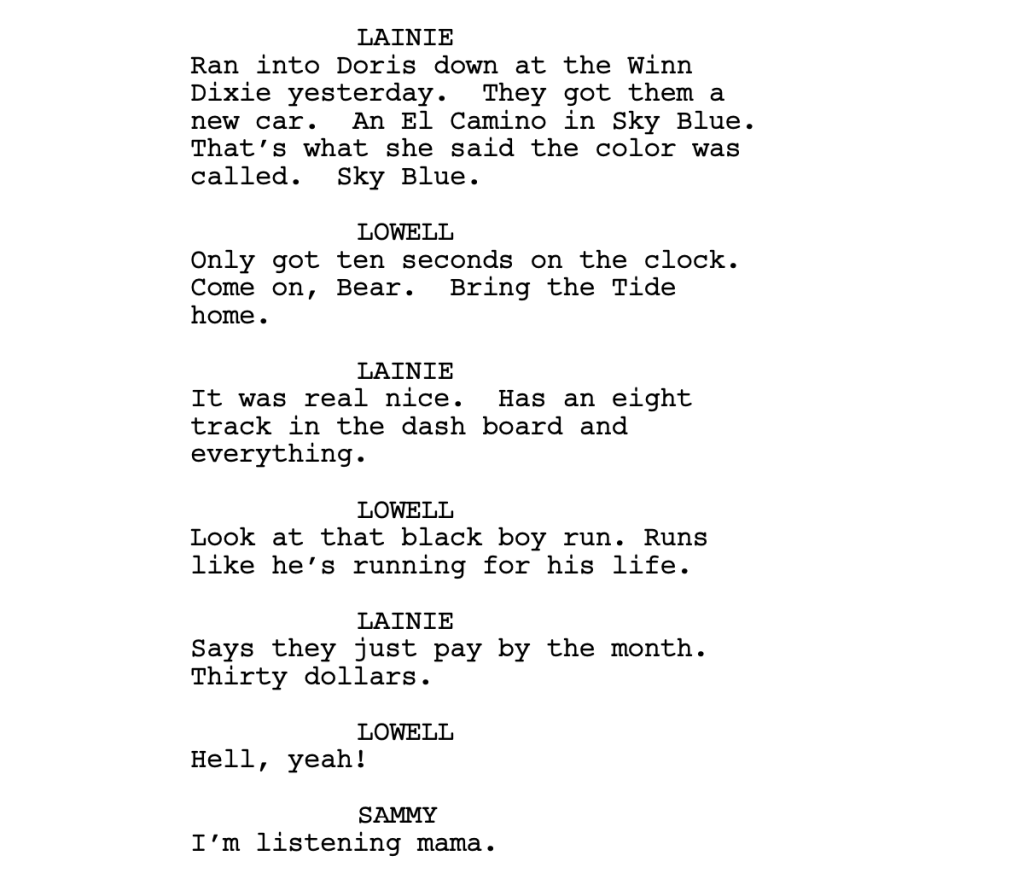

Take this early conversation from page 9. We’ve just come into the trailer for the first time. We’ve been introduced to his parents, Lainie and Lowell. Lowell is watching the football game, making Sammy hold up an antennae to keep the picture clear. Meanwhile, Lainie is going through the newspaper, looking at houses and cars for sale. We pick up the conversation mid-scene…

This is a dialogue tool that all of you should have in your arsenal. A lot of amateur writers get tripped up in assuming that dialogue must be logical. It must be a ‘your turn, my turn’ exchange of information where every question must be answered with a cohesive insightful response. No. Real life conversation is much messier than that. One of the cool ways you can take advantage of this is by writing conversations where the characters rarely, if ever, respond to the other character, which is what you see here.

But it’s not just a cool trick. Notice how this dialogue does three things. One, what Lainie’s talking about – wanting to get a nice new car so that she can look respectable – tells us EXACTLY who her character is. We know Lainie after this scene. Two, what Lowell talks about – his obsession with the game, his not so subtle racist remarks – tells us exactly who he is. This is a simple man with a simplistic view of the world. And three, it tells us exactly who these two are AS A COUPLE. Their (non) conversation tells us everything we need to know about this marriage within a minute.

That’s what great dialogue is. It’s entertaining in and of itself. But it’s also teaching us things about the people saying the words.

Another one of my favorite dialogue exchanges happens later in the script. **BIG SPOILER contained in the below example** We’ve hinted, at this point, that Lainie is sexually abusive towards Luke. But this is something that’s never spoken about in the house. In this scene, Luke has gotten ready for bed and is passing by Sammy and Rachel, who are on the couch.

Good dialogue does more than one thing at a time. At first glance, this scene is about Luke making fun of his brother regarding his lack of sexual experience. The dialogue is funny, albeit in an uncomfortable way. But take a closer look and pay attention to what Luke is saying. Luke’s sexual experience is limited as well, exclusively to his mother. So even though he’s offending Sammy here, what he’s really talking about is his own sexual abuse.

This is highly advanced stuff that I rarely see in screenwriting these days. Nobody understands subtext. Or, the ones who do, are too busy rushing through the script to come up with any clever ways to explore what’s happening beneath the surface. The writer is telling us, without having to ever tell us, that Luke is being abused by his mother. In bad scripts, writers will have their Luke character walk straight up to their mom and say: “You need to stop sexually abusing me mom!” “I’m not sexually abusing you.” That’s an uninteresting way to explore the issue. Instead, you want to talk around it, talk under it, talk about it abstractly, hint at it in conversations with other characters. Not only is that more true to life, it leads to much more interesting conversations.

I could go on about this script for a long time. I think the characters are, honestly, the kinds of roles that win actors Oscars. The structure is so tight that it makes what’s, essentially, a bunch of characters speaking for 90 minutes, go by faster than you can snap your fingers. And the dialogue is consistently awesome. It’s kind of reignited my belief that there are really good screenplays out there waiting to be discovered. Check it out for yourself and let me know what you think in the comments!

Script link: Spirit of Ecstasy

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This reinforces my belief that dramas can almost become de facto “thrillers” if you add a really tight time frame. For that reason, I encourage anyone writing a drama to consider tightening the time frame of your story. You may be shocked at how much it improves the script. As I told Ravin, “This doesn’t work if it takes place over one week. Or even two days. It works specifically because it takes place over 12 hours.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: Harvard. 1959. A young Ted Kaczynski is experimented on by Dr. Henry Murray during a secret CIA psychological study that may have led to the creation of the Unabomber.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 10 votes. Both of these writers have done a little TV work as well as written some indie features.

Writers: Adam Gaines & Ryan Parrott

Details: 91 pages

One of the most common things you’ll be tasked with as a working screenwriter is finding angles on topics that have no business becoming movies. Hollywood is so focused on snatching up life rights, biographies, and IP that they don’t actually ask if the ideas are something worth turning into a movie.

The Empty Man, which I spoke about yesterday, is a perfect example of this. It was some dumb comic book that nobody read. Yet someone decided to buy it. And then they pitched it to director David Prior, who went off to read it, came back, and said, there is no way I will make this movie because this comic is stupid as hell (paraphrasing). But I will keep the title and make my own movie. They wisely said, ‘fine.’

The problem with making a movie about Ted Kaczynski is that he’s an unpleasant wacko who possesses zero qualities that would make him a good movie character. He’s a disturbed weasel who sends bombs to people with crazy-person messages attached. That character can never ever be a protagonist.

And yet, here is the sickness that permeates the industry. Everyone is so desperate to get movies through the system, they’re willing to pluck these unpleasant, but popular, topics, off the idea tree, thinking that a sad bleak boring name is better than no name at all. And so we get a screenplay about Ted Kaczynski.

One of the weirdest things about this screenplay is that we’re never told, until the very last line of the script, what Ted Kaczynski did to deserve the treatment of a movie. If I’m 25 years old reading this, all I’m thinking is, “Who is this guy and why are we following him?”

I suppose this could’ve been an artistic choice. But something tells me the writers assumed that everyone would know who Ted Kaczynski was. Which is something you should never do as a writer. I didn’t know even know who Ted Kaczynski was. I thought he was the Oklahoma City bombing guy. While you may spend 200 hours researching someone and therefore know them intimately, a majority of readers will have no idea who they are when they first lay eyes on your script.

“Rewired” focuses on Ted’s life when he was 17 years old attending Harvard in 1959. He was a math prodigy who got recruited by a pretty teacher’s assistant named Barbara Martin into a psychological experiment at the university being run by a psychology professor named Dr. Henry Murray.

Murray asks Ted, along with the 50 other students in the program, to give him a thesis on how to live life and Ted comes back with a paper that basically states too many people in Harvard don’t need Harvard because they’re already set for life. Meanwhile, poor people like him have to scratch and claw just to keep up with their scholarship requirements and then, when they graduate, they’ll have to start all over again, since they don’t have a network of rich people to help them.

Murray then recruits a lawyer from the legal department and tells him to debate everyone in the group, breaking down their life theses, and making them feel as bad as possible about their ideas. His plan seems to be to destroy their beliefs to see if he can then build an entirely new belief system within them.

Halfway through the experiment, Barbara visits Murray’s home, only to discover that he’s babbling incoherently and randomly painting his walls with a long black stripe. Needless to say, this man should not have been conducting any experiments. But it was the 50s so there weren’t a lot of checks and balances.

Barbara tries to warn Ted that Murray’s experiment is evil so Ted goes to Murray’s office to quit. But Murray takes advantage of Ted’s youth and naiveté to convince him to keep going, which basically amounts to a lot more psychological abuse. Ted heads home for the holiday and is violent for the first time to his brother. His parents are concerned that something sinister is going on at the university and encourage Ted to drop out.

I’m not clear on if he did drop out or not because the last few pages of the script are vague. But I think he may have? And then we get a closing title screen that tells us Ted killed three people with mail bombs and injured 23 others. The End.

I mean… (my head drops to the desk)…

I don’t understand why people write these scripts.

This script is so f$%#%ing depressing and sad and rote and boring and nothing happens! It’s two people sitting across from each other for 90% of the movie.

Even the script’s intention doesn’t work – to build sympathy for Ted Kaczynski – because Ted is such a bummer himself. He lugs himself around campus, staring at the ground, talking to no one, when he does talk to someone he’s scolding them or getting upset. Why would we care about this person? They’re extremely unlikable. I don’t mean that in a screenwriting sense. I mean in a person sense. Like, I hate these kinds of people. So why would I care about a movie that follows one of them?

And this goes back to the point I made at the beginning: Not every well-known person in history is meant to have a movie made about them. Just because somebody did something spectacularly good or spectacularly bad does not mean that a film must be made about them. And yet Hollywood can’t help themselves. No soul left behind. No matter how boring or rote or unlikable or annoying or eye-rolling a famous individual is, we must make a movie about their life!

What I’d be curious about here is if any of what I read is documented – if these interactions between Ted and Murray came from a transcription – or if the writers just made them up. Because the conversations certainly felt made up, with the bad guys sounding like mustache-twirling villains from the 70s.

At one point the lawyer says to Ted, “Your father. Average sausage maker. Master bowler.” Ted replies, “How did — how did you know that?” The lawyer says, “Grinding it together as it grounds him down. You must know those casings are made from intestines. Tell me… do you help your father clean the intestines? So he feels like less of a failure?”

I apologize if these words are on record but I sincerely doubt it. They feel made up. If you’re going to tell a story this serious, you can’t just have a bunch of made up gibberish as it undercuts everything you’re trying to accomplish – which is to write a convincing portrayal of how this kid was manipulated. That’s the only thing the movie has going for it, is that authenticity.

Another issue I had with this script is that they’re squaring a Harvard professor off with a kid to challenge his ideas. However, Ted is psychologically weak from the get-go. He’s lonely. He doesn’t have confidence in himself. He doesn’t even really belief in his thesis. For that reason, the conversations are all one-sided.

Psychological battles are entertaining when the two parties are an equal match. Without that, it’s basically like watching a bully come into a room and beat up someone smaller than him again. And again. And again. And again. And again. And again. It’s masochistic. It’s unpleasant. I just… I’m so baffled about why anyone would think this would be entertaining.

Which brings us back to… yes, you guessed it: the fault of basing your movie on a weak idea. There’s honestly a more entertaining movie in two people trying to figure out how to spell Ted’s last name. We have to stop blindly putting scripts like this on the Black List because it means we will only get more of them.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is one more example that you cannot fix a bad idea. Whether it’s a bad fictional idea or a bad subject you’ve chosen. Writers lose years of their lives trying to make scripts work that will never work because the subject matter doesn’t work. This is one of those scripts. Nobody should ever make a movie about Ted Kaczynski. You can’t make him sympathetic. You can’t make the story entertaining. Anything you come up with will be bleak and sad. Nothing about this script works.

The Hollywood Reporter is reporting that Rogue Squadron, the Patty Jenkins Star Wars film that nobody other than Kathleen Kennedy asked for, has now been “delayed.” However, if you read further into the article, you learn that the delay is that so Patty Jenkins can “fulfill other obligations” on her other films (Cleopatra and Wonder Woman 3).

Hmmm… this sounds very suspicious to me. Star Wars was her priority project. Yet that’s the one she chose to put on the back burner? This is sounding like yet another forever delay (Lucasfilm’s new code phrase for “fired”). We saw this exact same thing happen with Rian Johnson’s new Star Wars movies. They’re still “delayed” (wink wink). I don’t know why this annoys me so much but Disney, dude. Be a man and just fire her. It’s okay to let someone go because their previous movie gave you pause on whether they could deliver a good Star Wars film.

I for one am thrilled by this development. As soon as the project was announced I rolled my eyes. Patty Jenkins is a bland filmmaker at best. Choosing her to reboot the Star Wars universe after what happened with 7, 8, and 9 very well might’ve destroyed the Star Wars brand for good. At least now it looks like they’ll start off with the Taika film, which has a much better chance of re-capturing the Star Wars magic.

You know I always have to report on the latest Star Wars news. Now back to your regularly scheduled programming!

Did Eternals Just Flatline the MCU? Also, a Secret Awesome Movie That Everybody Needs To See!

I want to start off by saying, good for Kevin Feige for taking chances. A lot of people give Marvel shit because they “play it safe.” I don’t think that’s true. I thought Thor Ragnarok was weird and different. Feige took a gigantic risk when he made a superhero movie with a 90% black cast. Even choices I didn’t like – a smart Hulk and a beer-gutted Thor – I must admit were huge bets.

And now comes Eternals, a movie with characters that have nothing to do with anything we’ve seen before in the MCU. Ten of them, to be exact. Instead of the fun swashbuckling nature that all the Marvel films exhibited before this, Eternals chooses to be slow, thoughtful, dare be it, meaningful. It is the biggest chance the MCU has taken yet.

And it is a complete failure.

The movie limped over the 70 million dollar mark this weekend but it’s now below 50% on Rotten Tomatoes, making it the worst reviewed Marvel movie of all time, a percentage that ensures a huge second weekend box office drop.

I have not seen the film. I woke up on Saturday thinking I was going to go. But as the day went on, a thought kept creeping into my head. Do I *have* to see this? Will I feel like I’m missing anything if I *don’t* go see this? The answer was no.

That reality metastasized into a larger discussion about what we’re trying to do as screenwriters. Isn’t creating a movie that people *HAVE TO SEE* the whole point of screenwriting? Should that not be the bar we set for ourselves when we come up with an idea? Shouldn’t we be asking, “If this became a movie, would people *have* to see this?” If the answer is no, why write it?

Here are some movies that, as they came out, I knew that I *had* to see them: Inception, The Dark Knight, Spiderman: Homecoming, 1917, Rogue One, Force Awakens, Get Out, Joker, Us, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Deadpool, A Quiet Place, Halloween, The Hangover, Parasite, Mad Max: Fury Road, The Social Network.

Why would I have to see Eternals? What special unique thing that I can’t get anywhere else is Eternals bringing to the table?

The reality is, Kevin Feige finally left the blackjack table and played roulette. He took, quite possibly, the most indie filmmaker of the last decade and gave her the reins to a 200 million dollar Marvel movie. What he got in return was Supheroland, the most boring looking superhero movie ever made.

You have a director who likes to create wide artificially blocked frames that stress stillness instead of activity and combined that with a near impossible screenwriting task – introducing ten different protagonists with ten different storylines. A lot of people have asked me how to write ensemble pieces since they’ve become en vogue during the superhero era (Avengers, Fast and Furious, Etc.). You do it by introducing the characters in their own movies so you don’t have to spend 70% of your movie setting people up.

It takes a certain amount of hubris to believe something like this could’ve worked. It has literally everything going against it. I guess when you experience as much success as Kevin Feige, you start to believe you can do anything. Now that that’s been proven wrong, what are the consequences?

Because here’s the upcoming slate for Disney (not Sony) Marvel movies:

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (May 6, 2022)

Thor: Love and Thunder (July 8, 2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (November 11, 2022)

The Marvels (February 17, 2023)

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 (May 5, 2023)

Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania (July 28, 2023)

Where is the sure thing? The first Doctor Strange didn’t light the box office on fire so there’s no guarantee this one will do better. Black Panther no longer has the actor who played the title character. How can that not hurt the film? I have no idea what The Marvels are and I don’t think anyone else does either. And Ant-Man is the lowest performing franchise Marvel has. The two movies that should do well are Thor and Guardians. But I’d say even Guardians is in trouble since the second movie was weak and James Gunn’s Suicide Squad turned out to be a dud. Throw in a post-pandemic box office lull and Marvel could be in serious trouble moving forward.

Should this be the beginning of the end of Marvel’s incredible run, people will look back at Eternals as the movie that started the slide.

Bummed out that I no longer had a movie to watch, I cycled through a few backup options. I started watching Finch on Apple TV and it wasn’t bad. But it wasn’t good either. The best way to describe it is that it was a 1990s Tom Hanks movie… without good directing or good writing. It had all the ingredients for one of those monster box office Hanks hits – Hanks doing a one-man show, his charm front and center, an impossible task with the highest of stakes. But the execution was so vanilla, you needed an industrial sized waffle cone just to make it through the first act.

So I went down my list and landed on a title several people have quietly been telling me to check out: The Empty Man. From what I understood, The Empty Man was a horror film that got lost in the mix once the pandemic showed up. It was dumped on HBO Max with barely a whisper. I looked it up on IMDB. Never heard of the director before. Never heard of the writer before. How good could it be?

Try the best horror film since A Quiet Place.

Wow was this movie good!

The film takes a very cliche horror premise – you call out to someone known as the Empty Man – and three days later, you kill yourself.

I challenge anyone to watch the opening of this movie and not get sucked in. It’s one of the creepiest – not to mention, heart pounding – 20 minutes you’ll watch all year.

But I’ll tell you when I knew this movie was special. You know how I always tell you: GIVE US SCENES WE HAVEN’T SEEN BEFORE. Especially in horror. Give us scary scenes that are fresh. That are new. If all you’re doing is recycling old scares, why would we give two shits about your script?

Well, The Empty Man has one of the scariest scenes I’ve ever seen. And a big reason for that is because it’s so original. Our main character, an ex-detective looking into the death of a friend’s daughter, follows a series of clues that leads him out to a remote farm where a cult is practicing all sorts of weird cult stuff. It’s night time. He’s safely tucked away in a forest, a stream between him and the cult, who are a good half-mile away, performing a ritual where 100 shaved-head members are jogging around a bonfire.

It’s a weird moment but there’s nothing overtly scary about it. Then the bonfire goes out. Total darkness. We can’t see anything for an extended moment. Our hero stands there, behind a tree, in silence, waiting. Then, just across the stream, the moonlight illuminating the tops of their shaved heads, he sees all 100 cult members, facing him.

Instead of being half a mile away, they’re now about 200 feet away. They don’t move. They don’t make a noise. For all he knows, they don’t see him.

He then takes a step back. As soon as he does this, they take a step forward. Silence again. He takes a second step back. They all take another step forward, their feet uniformly clomping down in a loud “thump.” The brilliance of the scene occurs in between the action. The director isn’t afraid to sit there in silence for what seems like days. Everybody still. Everybody silent. Everybody waiting for the next move.

Finally our hero turns around and runs. And all 100 cult members sprint after him.

I’ve never seen a scene like this in a horror movie in my life. Do you know how difficult that is to do? To create a truly original horror moment? It’s nearly impossible. You’re competing against millions of horror scenes. So when someone puts the work in to find that original scene, I know I’m watching something special.

And this director is definitely special. He’s Ari Aster but he actually understands screenwriting. One of the great things about this script is the mythology. The backstory for the empty man is so extensive, so weird, so layered, that you almost feel like you’re in a philosophy class. You’ve constantly learning things you’ve never even fathomed before. It’s so unique. I can’t stop thinking about it.

I understand why this movie got dumped. It’s got nobody you’ve ever heard of in it. It’s got a first time director. The studio needed to cut costs somewhere during the pandemic and spending a bunch of money to promote a movie that didn’t have anybody in it or making it that they could market was an easy decision. But dude, Warner Brothers. You had an all-timer on your hands here. This is an amazing movie. I hope enough people are able to find it. It’s one of the best horror movies of the last decade.

Quick final announcement. I came across an excellent drama script during a consultation that I’m going to review on Wednesday. Nobody in town knows anything about this script so it’s making its debut here. The writer is one of the best dialogue writers I’ve encountered in years. And, best of all, they’re allowing me to post the script. So you’ll get to read it yourself. We haven’t highlighted dialogue for a while on Scriptshadow. But this review is going to be all about dialogue. So make sure to tune in!