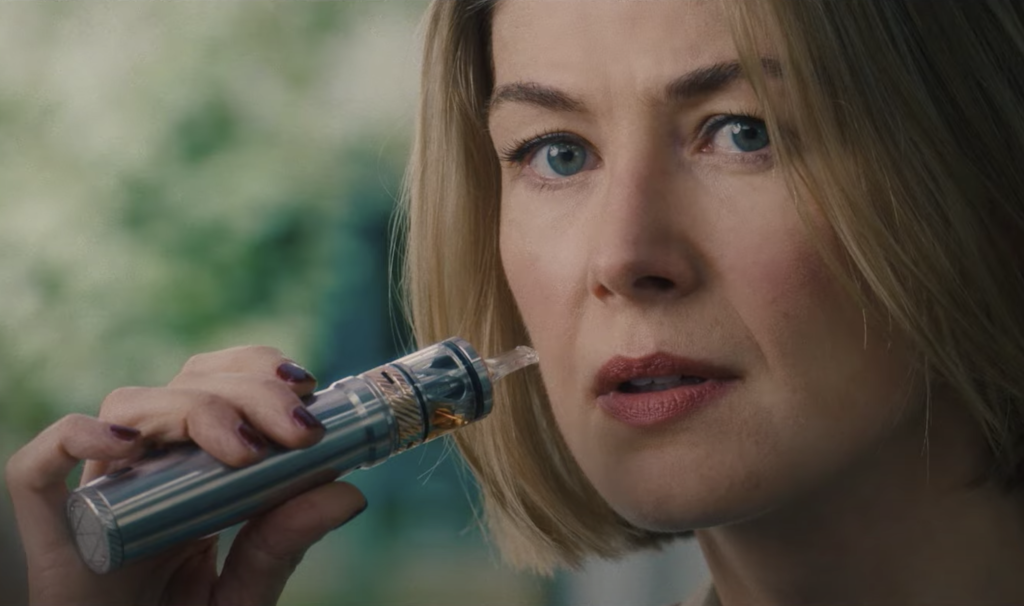

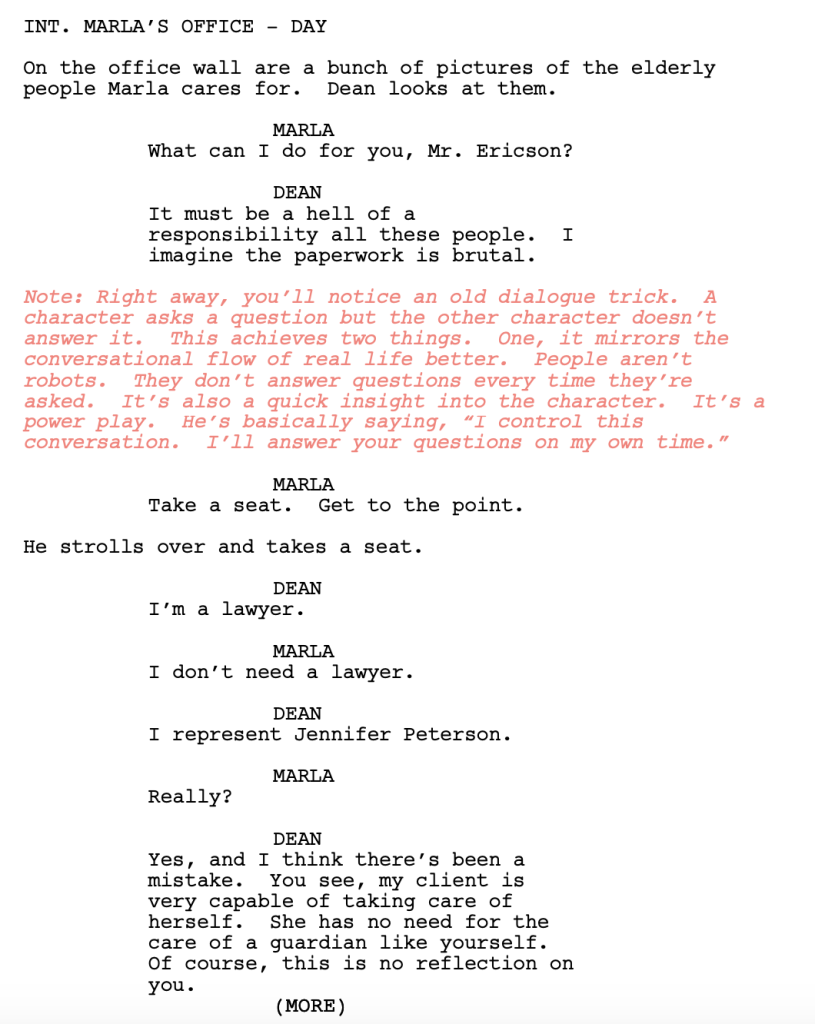

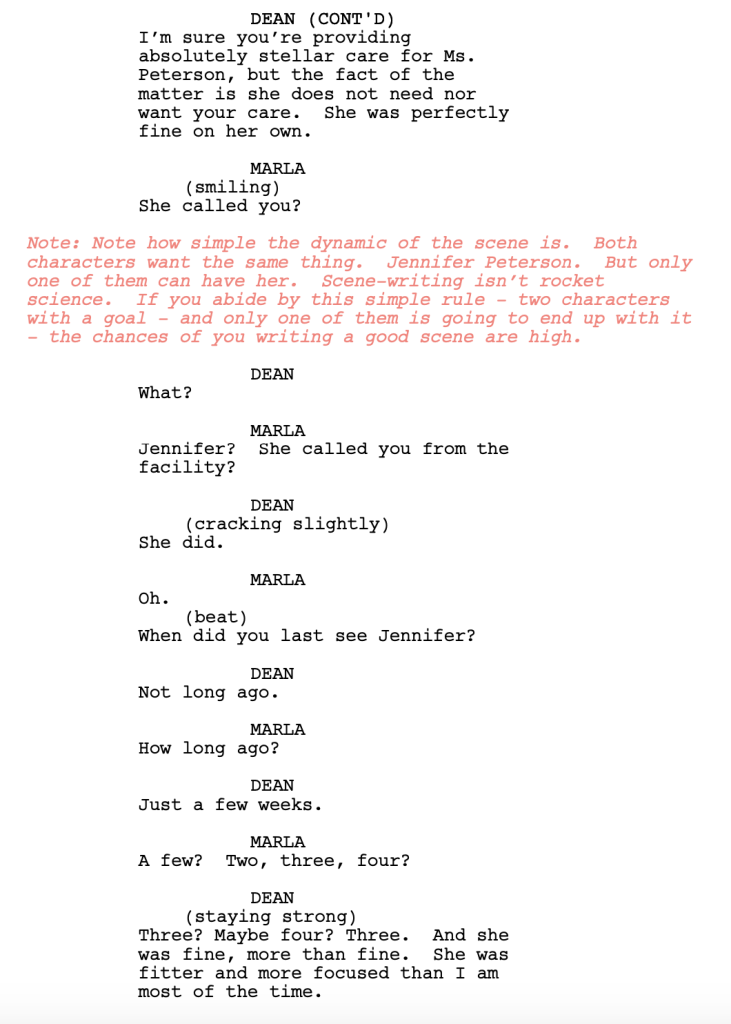

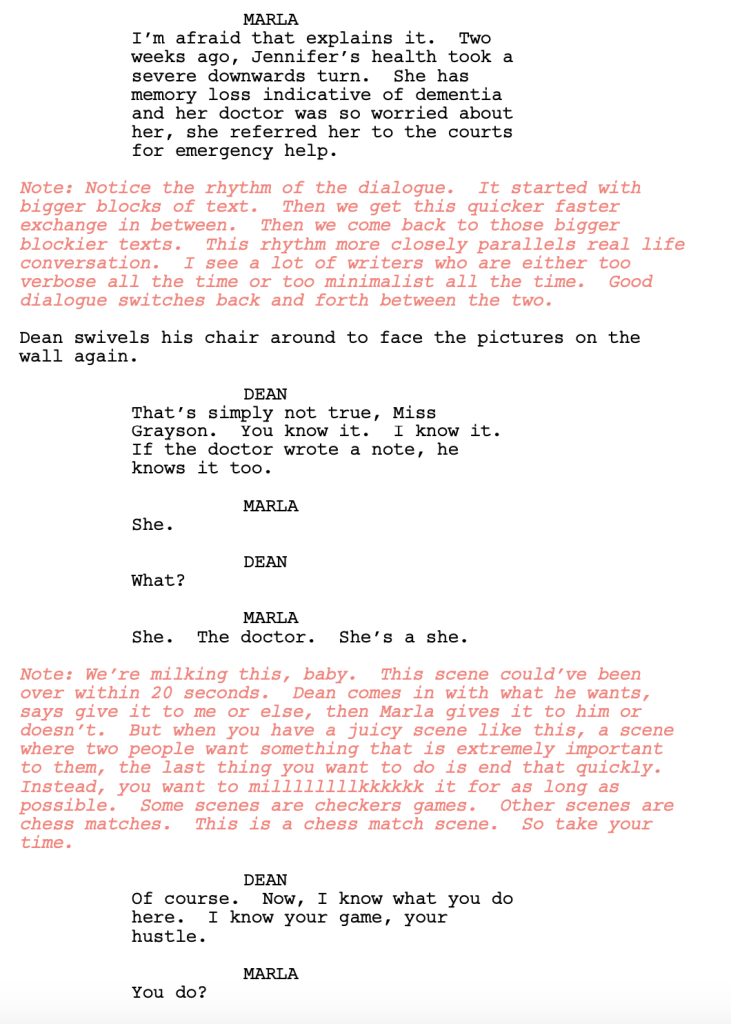

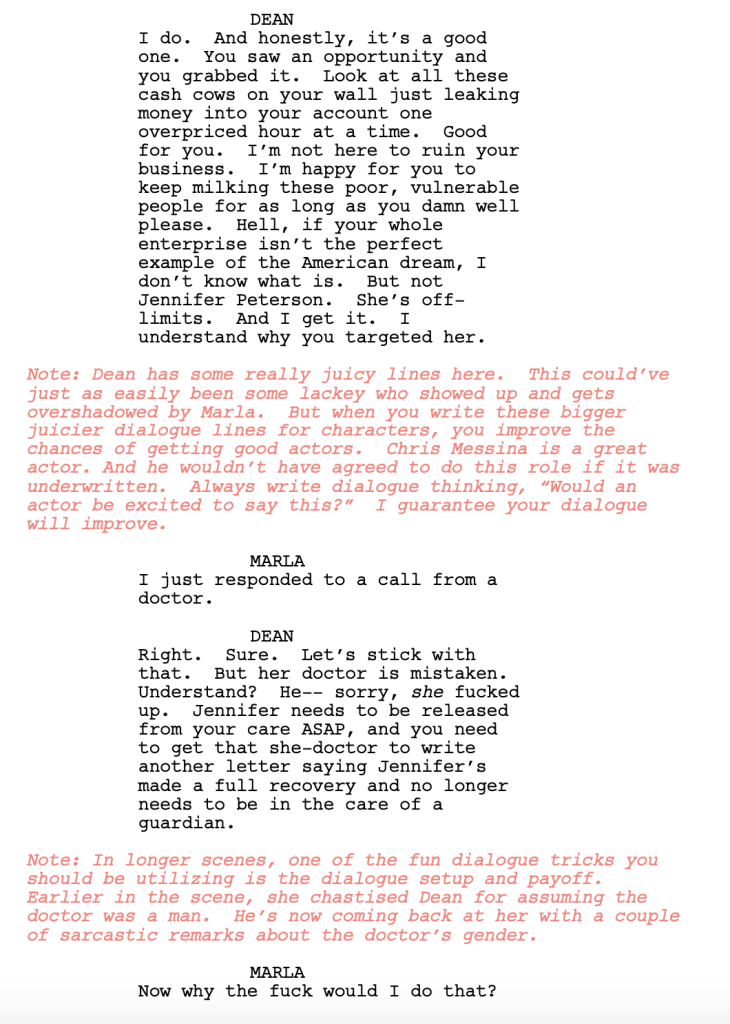

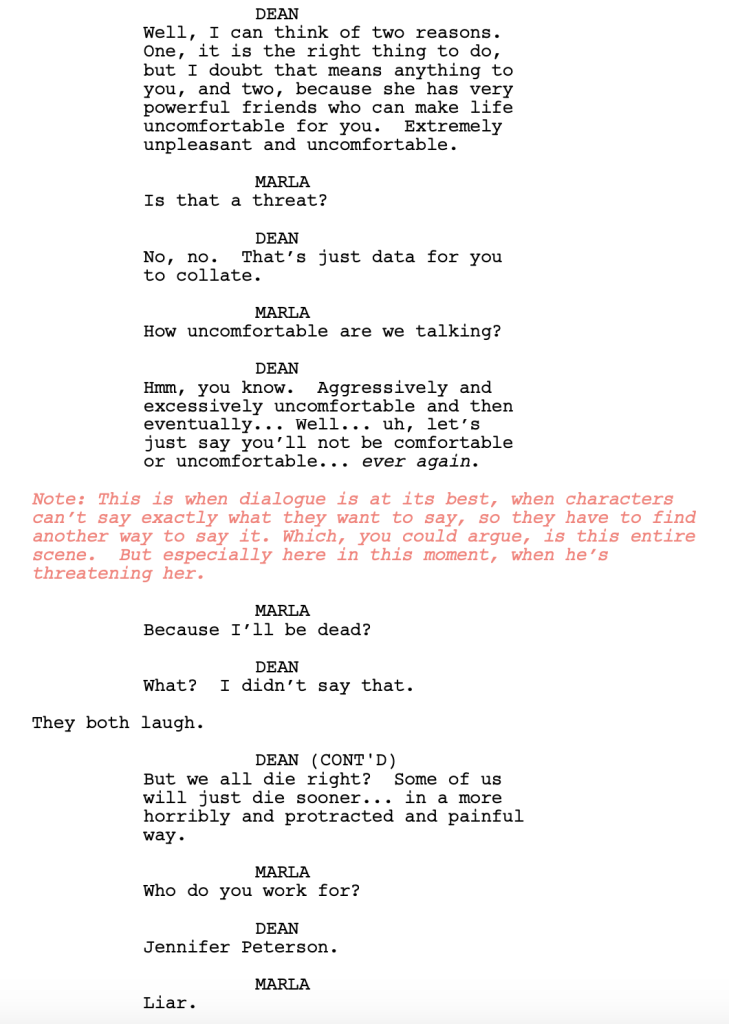

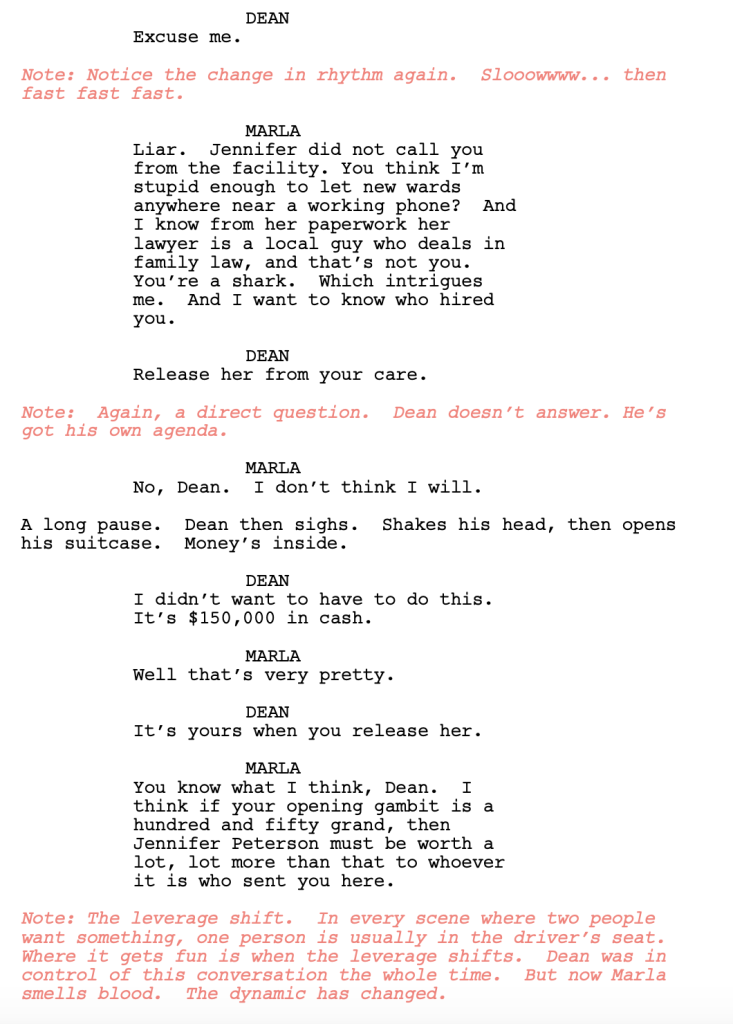

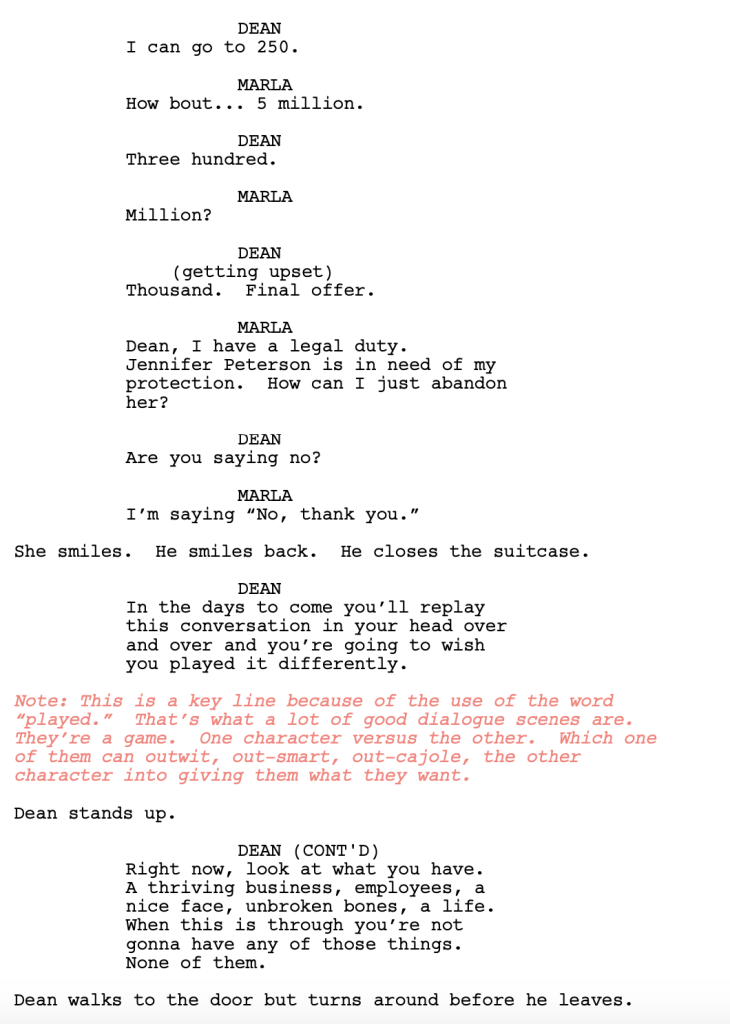

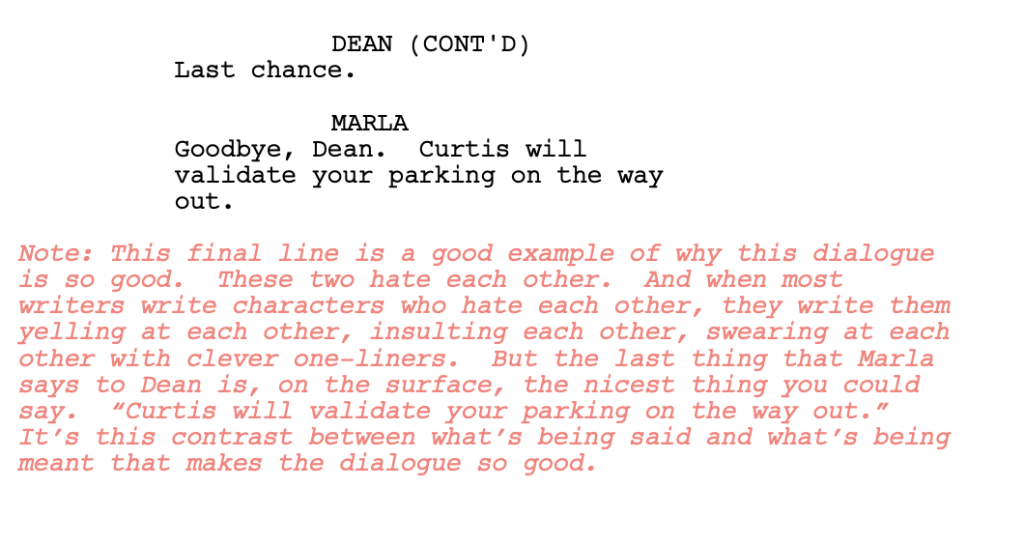

Recently, I started watching “I Care A Lot,” on Netflix. I’m halfway through it and, although I’ve been told that it falls apart, I like it a lot. Specifically, there’s a scene at minute 37 (if you want to queue it up) that I loved. In fact, it’s the best scene I’ve watched all year and has some of the best dialogue I’ve encountered all year. So I thought I’d transcribe the scene for you (this isn’t the official script) and explain why the scene is so good.

Here’s what you need to know. Marla is a professional guardian for older people who can’t take care of themselves. But Marla’s real racket is putting old people in homes who are perfectly fine and then stealing a ton of money from them. Recently, she’s put an older woman, Jennifer Peterson, in one of these homes. What Marla doesn’t know is that Jennifer Peterson’s son is a criminal kingpin. That’s where we pick up the story. A lawyer, Dean, has shown up at Marla’s office and wants to talk.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) A chemical leak in a local water supply in Central Florida wreaks havoc on the invasive population of pythons, leading a family to the fight of their life to survive.

About: This script finished with 11 votes on last year’s Black List. It is the writer’s breakthrough script.

Writer: Creston Whittington

Details: 110 pages

Today was an extremely long and difficult work day for me.

And, after it was all done, I had to read a script. And review it. Starting at midnight.

To say I was in the best mindset to read a script would be an untrue statement. But I bring it up because when you’re on the come-up, your script is likely going to be low priority to whoever’s reading it.

Which means it will probably be read under similar circumstances as to how I read this script – at the end of the day when you’d rather call it a night. Which is yet another reason to put everything you’ve got into your screenplays. Because while you can’t control outside factors such as the mood of the person who’s reading your script, you can control how much effort you put into your script.

Let’s see what we’ve got today.

We start out with some daunting local Florida history:

“Every year, the state of Florida sponsors snake hunts in an effort to exterminate the Burmese Python, an invasive specie introduced to the Everglades by the Exotic Pet Trade.

Although the low detectability of these snakes makes population estimates difficult, most researchers propose that at least 30,000 and upwards of 300,000 pythons likely occupy southern Florida and that this population will only continue to grow.”

20-something Sharon Esperanza has just got off of work (at the local aquarium) and realizes that her 12 year-old brother, Bobby, isn’t home. It doesn’t take long for her to realize what he’s up to: The Annual Burmese Python Hunt! That’s right. Here in Florida, once every year, you’re allowed to go out and hunt pythons.

Sharon finds Bobby and yells at him. This is the kind of nonsense that got their dad killed, she tells him. But Bobby tells her how fun hunting pythons is and why can’t she please let him. Sharon is reluctant but she figures if Bobby’s going to be hunting pythons, she might as well tag along to make sure he doesn’t get hurt.

Meanwhile, there’s this giant political backstory going on involving Florida gubernatorial candidate Pam Huntley. It’s discovered that Pam was first eaten by, digested by, then defecated by, a 30 foot long Burmese python. This news coincides with a park ranger being swallowed up by another python. Who’s being hunted here. The pythons or the people???

As the hunt continues, the death continues. But it looks like the pythons are winning! As Sharon’s news reporter mother looks into the cause of the sudden attacks, she finds evidence that the local corrupt politician has been working with a giant Florida pharmaceutical company and that the drugs they’re disposing into the water have turned these pythons into serial killers!

Will Sharon and her brother realize how bad this is in time to get back home and protect themselves from the snakes!? Or is it too late? Have the snakes found their way into each and every home in town!!????

I struggled with this one, guys.

Big time.

I think there were twenty characters introduced before page 10? Do writers realize that readers actually have to remember people? And if you introduce a billion people, there’s no way we’re going to remember them all?

There was also a ton of 5-6 line paragraphs. Look, you can write as many 5-line paragraphs as you want in a script. The reader’s not going to read them, though. You’re not gaming the system by squeezing all that extra information in. People who open scripts expect them to read fast. When the scripts don’t read fast, readers simply adapt their reading style to ‘skim-mode’ so that they do read fast.

On top of all this, this script is titled Reptile Dysfunction. When I open a script titled Reptile Dysfunction, the ratio of work to entertainment should not be 5 to 1. Scripts like this should be the easiest scripts to read in the world.

Yesterday we talked about dead relative backstories. Most movies have them. So it’s a common thing you’re going to be writing a lot. Which means you want to be good at it. You want to understand what works and what doesn’t work and make choices that are right for your screenplay.

In this script, after the opening teaser, we watch old home video footage of two people getting married, having a kid (Sharon), watching the kid grow up, graduate from high school, blah blah blah. And then, somewhere along the way, the dad dies. And we finally get to present day where we are now with Sharon as a young adult.

What that montage did was it created context for our main character, Sharon. We were “there” when her father passed away. The argument FOR this montage, then, is that we feel closer to Sharon than had we not gone through that experience with her. The argument AGAINST this montage is that it takes up valuable script time where we could already be into the story.

It’s no secret around here that people will give up on your script within a single page. Everyone on this site has done it. You have read one of those Amateur Showdown pages and thought, “Nope, not good enough to continue.” A montage like the one in Reptile is not story. It’s not entertainment. It’s not dramatic or suspenseful. All it is is backstory. It’s INFORMATION. When you’re giving people information, as opposed to drama, they lose interest.

Now you may say, “But Carson. What about Pixar’s Up? That started with a montage of two people meeting, falling in love, getting married and one of them dying, and it’s considered one of the greatest scenes ever!” That’s true. But that movie was ABOUT THAT RELATIONSHIP. The whole movie WAS THAT RELATIONSHIP so it made sense to start the movie with the montage of their lives together.

This, meanwhile, is a movie about anacondas attacking a Florida town. It doesn’t need that montage. Yes, I agree that it brings us a LITTLE closer to the main character. But I don’t think it’s worth it when you can just allude to the fact, along the way, that she lost her father.

Screenwriting is so funny. Yesterday was all about a premise that was too simple for its own good. It didn’t have enough meat on the bone. Then you have today’s script which takes a simple premise – snakes invading a town – and approaches it like it’s a Woodward and Bernstein biopic. This is so over-plotted and over-populated, it gets in the way of what the script is meant to do – which is to give the audience a good time.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: When it comes to fun ideas, get out of your own way. Anything that gets in the way of a fun read – long paragraphs, overly complicated plots with lots of jumping around, character counts in excess of 40 people – need to be eliminated. We’re picking up your script with a certain expectation of fun. Just like if someone thinks they’re about to read War and Peace and instead gets The Da Vinci Code, they’re going to be pissed, the same thing is going to happen if your fun-sounding premise reads like a history book.

Genre: Horror

Premise: When a dangerous stranger shows up at her front door, a depressed widow must confront her own past in order to protect her two children.

About: This one finished in the middle of the pack on last year’s Black List. The writer, Samuel Stefanak, was a writer on Bill Burr’s Netflix animated show, “F Is For Family.” He was also a staff writer on the Mario Lopez Netflix show, “The Expanding Universe of Ashley Garcia.” This project is being developed by Blumhouse.

Writer: Samuel Stefanak

Details: 98 pages

The best horror is simple.

Come up with a scary situation and let it play out.

Halloween. It Follows. A Quiet Place. Freaky. Dawn of the Dead. Lights Out.

These horror stories are so simple, it hurts.

So the question has to be asked: When is a horror idea TOO SIMPLE? When do you not have enough meat on the bone?

Today’s script definitely tests that question. Scary dude in the back yard. That’s it. That’s all we’re looking at here. Is it enough? I don’t know. Let’s find out.

30-something Ramona is still recovering from a bad car accident that took her husband’s life. Every night’s sleep produces another nightmare. And every day she has to look at her wounds (a bad arm, a bad leg) that remind her what happened. Since life if cruel, she has to put all that pain aside and raise her two children, 13 year old Ben and 6 year old Annie.

The family lives on the end of a dirt road in the middle of Nowhere, America. So they’re left to deal with this loss all by themselves. Well, except for today, that is. That’s because when Ramona begins making breakfast for her children this morning, she looks out the kitchen window and sees, 100 yards away, an old man in a black suit sitting on a chair.

It’s too far away to see who this man is or get a sense of what he may be here for. So all the family can do is speculate. The kids are scared. And so is Ramona. But Ramona’s trying to be an adult about this. If someone’s here to hurt them, why would he be chilling out in a chair a hundred yards from the house where they can clearly see him?

Against the children’s wishes, Ramona heads out to confront the old man, who greets her with a smile. He’s very kind. Asks her how her day is going. Apologizes for scaring her like this. But he just needed to sit down and rest for a minute. We don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to realize this guy’s lying through his teeth and it doesn’t take long for him to fess up. He wants to come inside. And if she invites him in, he’ll spare her children. If she doesn’t, all bets are off.

Ramona immediately turns around and marches back in the house, where she lies to her children, saying it’s just some old man who’s tired and needed a place to sit. Let’s go play board games. Ben doesn’t believe his mom and keeps pressing her for details. Oh, and in case you were curious, all lines of safety have been eliminated from the equation (power is out, phone is dead, car is kaput). So the trio don’t have many options other than to wait this out.

After a lot of squabbling, which gives us some additional backstory on Ramona’s car crash, Ben leans into the idea that he’s the “man of the house” now and has to protect the family. So he locks his mother in the bathroom, grabs his father’s old rifle, and marches out to confront the old man.

The old man is just as friendly to Ben as he was with Ramona, though. Even locates Ben’s missing dog that Ben suspected the man had killed. There’s no reason to pull that trigger, the man says, smiling. Frustrated that he didn’t have the guts to shoot him, Ben marches back inside. And that’s when the old man decides he’s had enough. He’s going to come into the house and finish what he came here for. He’s going to kill Ramona. And her children too.

To address my earlier question, I don’t think any horror idea is too simple. But the simpler an idea is, the more you have to nail these two things: First, you have to understand that coming up with your plot is going to be a lot harder than usual. Simple stories don’t offer as many plot opportunities. Which means you’re stuck rehashing a lot of the same stuff from other horror movies.

For example, if you have some psycho holding a character hostage in their basement the whole movie, you’re probably going to have to write the scene where they check every crevice to see if there’s a way out or something that can be used as a weapon. And since so many writers have written that scene before, it’s harder to come up with a version of it that feels fresh.

Second, you have to think a lot more about characters and character development. When situations are simple, the bulk of the story’s focus will be on the character (as opposed to the plot). So you have to ask yourself, “Is my character deep enough to withstand all of that focus?” “Is my character compelling enough?” “Is my character interesting enough?” “Is my character flawed enough?” Where these movies fail is when both the setup and the characters are too simple. Cause then there’s no depth anywhere.

Also, you want to add depth to ALL THE CHARACTERS. Not just the hero. Again, your story setup is too thin to only have one deep character to explore. It’s been done before but it’s really really hard. And, most of the time, the scripts don’t deliver if you’ve got an extremely simple setup and only one deep character.

In the case of “Man in the Yard,” we have a mother and two children. You can’t do much with a six year old character. They’re not old enough to instill any depth in. They don’t have enough life experience. So Annie’s off the table. You have Ben, who’s still pretty young. The writer gives him this story of “becoming the man of the house.” And while it’s okay, I never cared enough about it to feel any emotion around this character.

That left us with Ramona. And this is where the writer tried to install 98% of the story’s depth. She just lost her husband and she was in the car when he crashed. So there’s something there to work with. However, I see dead car backstories so often that it didn’t resonate enough with me. It just felt too familiar. And, for that reason, I never cared enough about this family that I was desperate for their survival.

Which basically leaves us with the man in the yard. There’s no doubt that a man sitting calmly in your back yard in the morning is a scary image. It sure as hell scared me. For the first 20 pages of the script at least. After that, I grew too comfortable. The element of surprise was gone. And while there was some suspense as to what he was going to do next, it all moved a little too slow for my taste.

Which brings us back to the initial question. Can a horror idea be too simple? No. But the simpler it is, the more work you have to do on the plot and character end to make up for it. And I don’t think Man In The Yard got there.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Stay away from low-hanging fruit plot options. Car crash backstory deaths are fairly common in writing. And the inevitable reveal about the crash always plays out the same way (the person who was supposedly driving wasn’t). I always encourage readers to go with something fresh and different. So if you want to include a backstory death, come up with something besides car crashes or cancer. Those options are low-hanging fruit and rarely yield exciting new plot opportunities.

You know there’s not a lot to talk about in Hollywood when you’re thinking, “Maybe I should cover Kim Kardashian and Kanye West’s divorce today. Maybe there’s some screenwriting tip we can draw from Kanye’s tweets.” I thought I had a juicy nugget to build today’s article around when someone sent me a link to “JJ Abrams’ Episode 8 Treatment.” The presentation was somewhat convincing. The treatment is a series of pictures (as opposed to a PDF) on red paper, the color that makes them hard to photocopy, and therefore preferred by writers trying to keep something from leaking. But I barely got to the second page before my b.s. meter started chirping.

It always amuses me when people say things like, “JJ Abrams doesn’t know what he’s doing! He only knows fan service.” Go ahead and read this treatment. This is what true fan service looks like. Within seconds of Rey handing Luke the lightsaber on the mountain, the two start dueling, Luke immediately jumping into exposition mode. “Did you ever ask yourself how an untrained pilot like you could suddenly fly the Falcon & outmaneuver those Tie Fighters? Then, somehow rendezvous with Han & Chewie shortly after? You know how to pilot the Falcon, because I know how to pilot th eFalcon. You beat Kylo on Starkiller because I was with you… aiding your untrained mind. It’s an old trick Jedi masters used to help their padawans.” You gotta love the ampersands, incorrectly capitalized words, and randomly placed commas, lol.

I was bummed it was fake cause I wanted something to talk about today. But then I realized I hadn’t updated everyone on my producing endeavors in a while. So guess what? I’m going to do that right now!

PRIORITY NUMBER 1 – KINETIC

For those of you who visit the site less frequently, Kinetic is the script that won my contest. The logline is: “Following a harrowing phone call while out on the road, a long haul trucker with a tormented past must deliver a tank of liquid crystal meth before sundown in order to save his pregnant wife.” If you remember, I told you that our number one priority was attaching Gerard Butler. So we first went to Millennium, a production company he does a lot of movies with, and they passed. As soon as that happened, I was able to get the script to Butler’s gatekeeper through a mutual friend. And that’s where it is now.

All I can do at this point is wait until she reads it. One of the most frustrating things about this business is the waiting game. Especially when you’re low on the priority list. Until I’ve got movies under my belt, it’s going to be a grind. And I know that. I’m not afraid of that. If Butler doesn’t work out, I’ve got the next three steps ready for Kinetic. Cause here’s the thing with Kinetic. And it’s something I’ve never really had with a project before: THIS IS GOING TO BE A MOVIE. It’s too perfectly suited to become movie for it not to become a movie. It’s too guaranteed to make money for whoever produces it. It has all the elements that result in a profitable fun film. And not only that. If the execution of the film is as good as this script, it has the potential to become a franchise. So all I have to do is keep getting it to people. There’s no question, in my mind, that, sooner or later, one of those reads is going to lead to the project getting greenlit.

PRIORITY NUMBER 2 – MOTHER REDEEMER

Here’s the logline for Mother Redeemer for those who don’t remember: “After a devout member of a small religious sect receives a sign from their God that she will be the mother of Earth’s messiah, she must find a way to protect her divine child from the cult’s corrupt leader.” Mother Redeemer is an interesting project because I’ve been sending it out and getting lukewarm responses. Now, here’s the thing. I know this is a good script. I read scripts like it all the time. And this is a cut above all of them. But the script is undeniably a slow burn. And what I’m realizing is that the hardest kind of spec script to get people excited about is a slow burn. The spec scripts that work best on the market are scripts like Bullet Train or Kinetic. Stuff that moves quickly on the page. Mother Redeemer is all about ‘build’ and tension and suspense, all of which it does beautifully.

I suspect that the people reading it aren’t sticking with it long enough to lose themselves in it. The reason I suspect that is because the same thing happened to me when I first read it. The main reason the script made it through the “First Ten Pages” round was not because I was enamored with the story. I simply recognized that the writing was strong. Then, when I started reading the script in the second round, I remember being on the fence about it 25 pages in. I specifically remember being tired and wanting to go to sleep. Then I thought, “Ehhh, I’ll finish it up so I have more time to myself tomorrow.” And, from there, every 10 pages, the script got better. And better. And better. And by the third act, my face was two inches from the screen, I was so into it. The dirty little secret about script reads is that nobody owes you a full script read. If they’re bored on page 20, they may decide to not read the rest and tell you they did. It’s not like they’re going to be quizzed about it. I suspect that might be what’s happening here. People aren’t making it past that same threshold in the script that I made it past where the script got infinitely better. So, the writer, Brian, and I, are trying to address this issue and make those first 20 pages read quicker. I still have a ton of confidence in the project. It could literally be made for 3-5 million dollars and it’s got two AWESOME roles for actors: the young pregnant woman (think Margaret Qualley) and the cult leader (think Michael Shannon or Adam Driver). I would love to get a Jennifer Kent (Babadook) to direct this. Ultimately, it’s going to be about finding people who, like Brian and I, are fascinated by the cult world.

PRIORITY NUMBER 3 – MANIACAL

You guys might not know about this horror project yet. Here’s the logline: “A teenager is forced to protect her half-siblings when mysterious masks begin appearing around the world that compel people to put them on, turning them into homicidal psychopaths.” It comes from co-writers Andy Marx and William McArdle. The two made the finals of my contest with their script, Crescent City (“A woman with the ability to control ghosts is forced to protect a witness being hunted by supernatural assassins.”). So why am I focusing on Maniacal instead of Crescent City? Simple. It will cost 1/10th as much money to produce. This is a 3-5 million dollar movie. Crescent City is a 30-50 million dollar movie. It’s John Wick with a female lead in the voodoo world. And it’s a movie I want to make badly. But Maniacal feels like the clearer path to victory, right now. And then, once we get that movie made and the writers have some heat on them, we’ll pitch Crescent City. Because I think Crescent City has the most upside of all of these projects. It could become a HUGE franchise.

The writers and I are currently fixing a few issues with the script. One of the main problems was that the mythology was a little thin. This crazy stuff starts happening all around the world and I wasn’t convinced that the reader understood what was happening. So we’re adding more scenes that give us insight into what’s going on. The thing I love about Maniacal is that it harkens back to those fun horror movies they made in the 80s. Simple but scary. And I love this hook of, what if you woke up one day and everyone was Michael Meyers? It wasn’t just one guy. What do you do? As soon as we get the script right, we’ll start targeting the horror production companies.

REST OF PROJECTS

What else am I working on? Contest finalist, That Wind Come Down (“After taking the fall for a horrific crime and spending twenty five years in prison, a neurologically disabled ex-con must confront his troubled past as he desperately tries to find a kidnapped young woman who’s disappearance may be connected to his past transgressions”) is still in the development stage. The script made the finals mainly on the talent of its writer, Chris Rodgers. But the story needs to go through a maturation process before it’s ready for the market.

I still have to re-read Tighter (“When a Japanese rope bondage workshop is taken hostage by masked intruders, a couple must find a way to escape their captors while tied together at the wrists”) and give Arun Croll notes. I’ve been slammed wall-to-wall with work so I haven’t been able to find the time yet. I found this amazing writer who wrote this great NASCAR pilot about a race car driver who finally gets a chance to shine after the retirement of his famous father but then his father wants back in. It’s basically NASCAR meets SUCCESSION. This might be the best-written thing of all the scripts I have but I’m struggling to understand the TV world. It’s something I don’t know as well as the movie world. So this might take a little longer to get through the system as I educate myself (feel free to e-mail me if you have advice cause this pilot is better than 95% of the stuff on TV right now. It deserves to be made).

I’m also working on a unique tennis project called, “Loser.” Let’s just say it’s unlike any sports movie you’ve seen before and is built around the premise of a professional tennis player who loses… a lot. There’s a script from long-time Scriptshadow reader, Alexander Bashkirov (who’s had tons of scripts reviewed on the site) called “Scorcher,” which is an action thriller with a REALLY fun premise that we’re working on. And there’s a thriller set in India that I hope to share more about in the coming months.

A couple of final thoughts that can double as today’s “What I learned.” Think hard about writing slow-burn spec scripts. They aren’t naturally suited for the spec market, which favors faster moving stories. Don’t get me wrong. If they’re great, they can get you noticed. But there’s no question you’ll have to send your script out to more people than you would if you wrote a more spec-friendly genre. Also, one of the things about sending your scripts out there is that everyone is going to tell you why your movie *can’t* be made. Back to the Future, one of the greatest movies ever, was famously rejected by everyone. The Anchorman creators were famously told by one studio to never EVER send them a script like that again, lol. It took John Lee Hancock, who has a successful career in the business, 30 years for someone to finally let him make The Little Things. The point is, there is no script that automatically goes to the front of the line. It’s always “Here’s why this doesn’t work.” Your job as a producer, or as a writer promoting their own script, is to not take these critiques personally and understand that they’re part of the process of getting a movie made. No movie has ever been made without people persevering through a lot of adversity. If you believe in a script, keep going until the cameras start rolling.

Have a wonderful week, guys. And if you’re a production company or director or financier or actor who wants to be involved in one of these films, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com. Get in before it’s too late! :)

One of the interesting things about reading all those scripts in a row for my contest was seeing so many scripts fall apart in real time. Which was frustrating. You want every script to be good. And with all these scripts passing the “First 10 Pages Test,” your expectations are already high.

So why is it, then, that so many scripts start off strong, then fall apart?

I remember reading semi-finalist script, Wish List. In case you forgot, here’s the logline: “An Amazon delivery man is ambushed in Mexico by a group of gangsters who mistake him for a drug mule, and must survive using only the packages inside his van.” The opening teaser followed an Amazon delivery guy (not the main character) who’s attacked by a crooked Mexican cop. He doesn’t get out alive, establishing the stakes for when we meet *our* Amazon delivery driver.

It didn’t take long for me to lose some of that early confidence in the script. The main character was a bit too goofy for my taste. He reminded me of someone Kevin James might play. Which is fine if you’re writing a comedy. But this wasn’t a comedy. The driver is soon trapped by a Mexican cartel and his situation is anything comedic.

A great concept is both a blessing and a curse. It’s a blessing because it gets you more reads. It’s a curse because you now have to live up to that great concept. That means you have to be as clever as your logline implies. And this is where the edges of Wish List started to fray.

Let me be clear about something first, though. Wish List doesn’t make any big mistakes. The mistakes it makes are actually quite average. Unfortunately, that’s all it takes for a reader to lose interest. You guys know this. You read scripts from the site all the time. The second an even mildly questionable writing choice is made, you raise an eyebrow, and by the time a second one arrives, you’re out.

Wish List already had one strike against it because I didn’t feel the tone of the hero matched the tone of his predicament. Then, once the driver started using his packages, that’s where my interest dropped for good. When you have an idea like this, you’re looking for interesting packages the driver uses in clever ways.

The first package we open is an iPad, which the driver uses to translate what the bad guys are saying outside, which was okay. But the only reason he had to do that was because he didn’t have his phone. A phone could’ve done that as well. So we’re not using things in a clever way yet.

Now the driver has to find a phone to call for help. So he starts opening packages until he finds one. However, the only phone he finds turns out to be a kid’s phone, which doesn’t have all the adult features. Which is sort of clever. You always want to make things hard for you hero. Not giving him a fully-featured phone does make things harder than if he had an iPhone. But that’s two packages so far where I’m not seeing much ingenuity. I’m not seeing anything clever. And that’s the whole reason I picked this script.

So even though I would continue to read, my heart wasn’t in it anymore. And that’s how quickly a script can fall apart.

In the case of Wish List, I don’t think the writer made any giant mistakes. I just think he underestimated what the bar is for a good script. Scripts like this are all about the choices you make. It’s how imaginative you can be with those items. If I were the writer, one of the first things I would’ve done was google, “Top 100 things ordered on Amazon” and obsessively combed through the list. You’d probably come up with 50 fun ideas to play with.

But the bigger lesson here is: Don’t assume the movies you see made are the bar you must hurdle. The bar is actually a lot higher than that for any spec screenwriter. You have to write something great to get people interested. It’s only later that over-development and bad notes from studios execs and maybe a director who doesn’t know how to write will ruin your script. But to get to that place, it first has to be great.

Another script whose first ten pages I loved was Honey Mustard. We meet this woman, Stella, who’s married to this utterly awful excuse for a human being. A guy who’s pure evil. The first ten pages is all about her reaching her breaking point and killing him. It’s a really intense first ten pages so I had high hopes for this one.

We then meet this other character, Buford, who’s having a really tough time of it. He’s out of a job. He’s got a family to support. We see him get coldly rejected after an interview. So he’s having a lousy day too.

What happens next is we follow Stella to her workplace. She’s a waitress at a diner. And her first customer is, guess who? Buford. Clearly, neither of these two are in a good place and we can feel that undercurrent of tension in their interaction. Which is credit to the writer who did a wonderful job of setting up the immediate backstory of these two characters to create this charged moment.

Buford gets annoyed when Stella keeps forgetting to bring him honey-mustard sauce for his order. He keeps reminding her and reminding her and reminding her. But she’s dealing with her sexually harassing boss and a handful of other impatient customers and she just killed her husband, so yeah, she’s a little distracted.

So Buford does something really mean. In order to get her back, he doesn’t tip her (he puts “Honey Mustard” on the tip line, lol). And off he goes.

We then follow Buford home where he gets some good financial news. And maybe, just maybe, his family is going to be okay. Meanwhile, we cut back to the diner…. AND EVERYONE IN IT IS DEAD. They’ve all been shot and killed. The cops are trying to figure this out. Stella is not there so she’s their first suspect.

We then cut back to nighttime at Buford’s house. Buford starts seeing a car drive past his place repeatedly. He gets worried. Then he sees the words “HONEY MUSTARD” finger-written through fog on the window. And he realizes that the waitress is here to kill him and his family.

So where did everything go so wrong so fast? Simple. There should not have been a mass-killing at the diner. Literally, the second that happened, I said to myself, “This script is done.” And every subsequent page further supported that. The reason this script was so strong early on was because everything was character-based. It was all about setting up the characters’ lives and then watching what happens when those lives collide.

The second you turn it into a mass-killing, it becomes a whole other movie. And not the movie that you set up, by they way. This isn’t “Unhinged.” However, a part of me understands why the writer, Michael, made these choices. He’s been told time and time again, by people like myself, that THINGS NEED TO KEEP HAPPENING in a screenplay or else the reader will get bored.

Fearing that his script was TOO character-driven, he went all in on taking things to Mach 10. But here’s the thing. When you write good characters, you don’t need a bunch of fireworks. This script could’ve survived as a slow-building character piece. You could even add 3-4 other characters, whose lives we follow, and then have all of them collide in the ending. But turning Stella into this (potentially) mass-killing house-invader was the least interesting choice you could’ve made after that setup, in my opinion. You started with believable and switched to unbelievable in a heartbeat.

So what can we learn from these two scripts? First, deliver on the promise of your premise. And start to do so early. You have to prove to your reader that you’re going to give him what he paid for. Jurassic Park does a great job of this with the whole mosquito-blood scene. I remember watching that and thinking, “Wow, that totally makes sense for how they’d be able to create dinosaurs in modern day.” It was clever and it hooked me.

Next, don’t feel like you’re serving a stadium full of ADD-riddled idiots when you write a script. The problem with that mindset is you think you have to have a car-chase (or a “car chase equivalent”) every scene. So you end up writing these great big plot developments when the script doesn’t need them. It’s hard to be patient as a writer. But just remember that, if you write great characters who are involved in interesting situations, readers are going to want to keep turning the pages.

Finally, have a plan for your second act. This is where most scripts fall apart because it’s the moment where the writer has to actually write the story. The first act is just setting up the concept you came up with. But the second act is where we need to feel like there’s a plan in place. We need to feel like the characters have goals or a clear direction. If it helps, break your second act into four sequences of, between, 12-15 pages. Doing so is automatically going to give your act more structure.

If you go into the second act with only a vague sense of what you’re going to do? It’s going to show on the page. You can’t hide it. A reader senses when the person telling the story isn’t quite sure where he’s going. If you hate outlines, that’s fine. But it means you’re going to have to do a lot more rewriting on your second act to get it to a place where it feels purposeful. If you do these three things, you should be good to go!

By the way, I’m curious what your thoughts are on Honey Mustard and Wish List. I still think both these scripts have potential. So, what are your fixes?