We’ve got three months until the Comedy Showdown deadline (June 17). Three months is plenty of time to write a script. And that’s what I’m going to help you do. Every Monday, until June 17th, I will be guiding you along in the process. This way, you don’t have to think about when and where to work. I’m going to provide you with every step. All you have to do is do what I say.

By the way. I don’t want to confuse anyone but I already know what the next Showdown (which will take place in September) will be. It will be a Sci-Fi Showdown. I’m not officially announcing it yet. I’m just letting you know, in case comedy’s not your thing, you can use this time to write your sci-fi script, and then have a whole extra three months to make it perfect.

So, what is going to be required of you? A minimum of two hours a day of writing. And, yes, you’ll be writing seven days a week. You have that time. You may think you don’t. But I promise you you do. Chris Dennis, who wrote Last Great Contest winning script, Kinetic, has three children. And he still managed to write two screenplays over the past year. So you have time. Just stop watching so many stupid Youtube political videos.

While I’ll be stressing comedy during this exercise, I’m basically going to act as a script-writing motivator. I’m going to give you tasks and your job will be to complete them. So even if you’re not going to enter Comedy Showdown, feel free to write a script in another genre. When else are you going to have an angry website owner standing behind you with a whip?

Last week, I gave you your first task. Come up with a concept. If you failed at that, I’m going to offer you a last second comedy concept hack. One of the easiest ways to come up with a comedy idea is to take a movie in another genre and simply turn it into a comedy! Take John Wick… and turn it into a comedy! Take a heist film, like Triple Frontier… and turn it into a comedy! 1917 made hundreds of millions of dollars on top of the one-continuous-shot gimmick. Why can’t you make hundreds of millions of dollars on a one-continuous-shot comedy!? The possibilities are endless.

Okay, so we’ve got our concept. Now what?

I need you to brace yourself.

And make sure you’re sitting down.

This week… IS ALL ABOUT OUTLINING.

Your outlining will be broken into two sections. The first section will be three days and consist of getting to know your characters. The second section will be four days and consist of writing a physical outline.

Day 1 will consist of getting to know your main character. Specifically, you’ll want to know what their fatal flaw is. While the need for a fatal flaw in every movie is debatable, it’s not debatable in comedy. In comedies, your main character needs conflict within himself about SOMETHING. Something needs to be unresolved. Your hero may be aware of what that something is. Or they may not.

Happy Gilmore has anger issues. That’s his flaw. That’s what he needs to resolve. Seth Rogen in Knocked Up isn’t ready to be an adult yet. That’s what he needs to resolve. Columbus in Zombieland struggles to connect with others. That’s what he needs to resolve.

Your concept will usually tell you what your hero’s flaw is. Bridesmaids is about a bridesmaid who has to compete for attention with the bride’s new friend. The flaw we give to our main character, then, is pretty obvious. Jealousy. Kristin Wiig has to resolve her jealousy by the end of the story. That’s the thing with this stuff. It’s not rocket science. The answers are often right in front of you.

Next, you’re going to do a character biography. I know that all of you hate character biographies. So I’m going to give you an option. But, first, for the purists out there, I want you to write between 2-5 pages of some key details in your hero’s life. I want to know where they were born, where they grew up, what their relationship with their parents was like, their first kiss, their first sexual encounter, their religion (or lack thereof), their best friends, the most traumatic thing that ever happened to them, their current relationship (or marriage), their education, their job, and finally, whether they’re happy or not in life. And, if they aren’t, why?

What you write isn’t important. In fact, you may never look at this document again. The idea is to get you thinking about your character. And that’s what this exercise will do. I guarantee you’ll come out of it learning something exciting about your hero.

If you don’t want to write a biography, go ahead and open up a new document in Final Draft. And I want you to write out, in script form, the beginning of your main character’s day. The more detailed you are, the better. This will achieve the same thing. It will make you think about who your character is. You can learn a hell of a lot about someone by how they start their day. Is it timed to the second and perfectly ordered? Or is it wake up whenever you want and figure out what to do on the fly? Have fun with this. We’re writing a comedy.

Day 2 will be focused on your secondary characters. I need you to write down two things about everyone outside of your main character. I need to know their fatal flaws. And I also need you to assign them a DEFINING CHARACTERISTIC. Almost all the characters in a comedy are funny. What you’re doing now is deciding HOW THEY’RE FUNNY. And you do that by assigning them a defining characteristic.

If we’re to use The Hangover, Alan’s defining characteristic is that he’s the world’s most socially unaware person. Stu’s (Ed Helms) is that he’s paranoid about everything. Phil (Bradley Cooper) is selfish and hates his life. If that sounds like a weak defining characteristic, that’s because it is. Of the three main characters in The Hangover, Phil is the most forgettable. Which is why getting the defining characteristic right is so important. It will decide how funny and how memorable that character is.

Day 3 will be focused on whichever one of the first couple of days you weren’t able to finish. If you still don’t feel like you know your main character, get back in there and write more of that biography! If you still have secondary characters to figure out or don’t feel like your defining characteristics are strong enough, go back in there and keep working.

Day 4 is going to be about about figuring out your structure. You want to know what your first act is going to be about, your second act, and your third. If you need help, remember that the nicknames for these acts are the SETUP ACT, the CONFLICT ACT, and the RESOLUTION ACT. So I want you to think about how your concept can be extended out into this construct.

Let’s look at the famous Chevy Chase comedy, Vacation. The first act is going to be setting up the members of the family and the family dynamics. The second act is going to be the drive. This is where the characters attempt to get to their destination. You’ve going to want to come up with a series of obstacles that get in the way (this is the CONFLICT ACT and obstacles create CONFLICT). And then the final act is them getting to their designation, only to find out it’s closed.

Days 5, 6, and 7 are going to be physically outlining as much as you possibly can about the movie. Your starting points should be the inciting incident (usually, this is the thing that causes the problem that the main character must now deal with – like Seth Rogen getting Kathryn Heigl pregnant in Knocked Up). The first act turn (page 25 in a 100 page script) is when the character goes off on their journey. The midpoint shift (page 50 in a 100 page script) is when something major happens that changes the entire dynamic of the plot. In The Hangover, this is when Chow informs our protagonists that he has Doug and will kill him if they don’t pay him back his 80,000 dollars. The end of Act Two (page 75 in a 100 page script). This is always an easy plot point to figure out. It should be your hero’s lowest point where he’s given up on achieving his goal. And, finally, your ending. You don’t have to know your ending just yet. But it helps to know it early because then you can start writing “set up” scenes throughout the script.

If all you accomplish is figuring out those pillars, you should be good to go. But I would encourage you to add as many checkpoints to your outline as possible. Checkpoints are any scene idea or plot development that you come up with. If you’re writing Borat 2 and you know you have a scene where the daughter goes to a doctor for breast implants, that’s a checkpoint scene. If you know you want Borat and the daughter to split up somewhere around page 67 (midway between the midpoint and end of second act), that’s a checkpoint scene. This is how they write Avengers movies. The writers just figure out where all the checkpoints are so they know where to write to.

Another option for outlining is the sequence method. This is where you divide your script up into eight sections. If the script is 100 pages long, each section will be roughly 12 and a half pages. Some writers like this because it turns this big endless 100 page black hole into more manageable chunks, each of which are, essentially a “mini-movie.” So instead of writing one big movie. You’re writing eight mini-movies.

And you’re using the exact same methods as you would in a big movie. You want to come up with a goal, some stakes, and some urgency for the first mini-movie. Then you come up with a new goal, stakes, and urgency for the second mini-movie. And just keep doing that all the way down the line.

Guys. Comedy is one of the most structured of all the genres. It is in your best interest to spend 14 hours this week outlining. It will make everything so much easier when it’s time to write.

And that’s it.

Next Monday, we’ll start writing the script!

Genre: Black Comedy/Thriller

Premise: When a freak storm hits a couples therapy retreat and turns all men in its path into predatory killers, a devoted wife and her new female allies must fight to save their lives, as well as their relationships.

Why You Should Read: MAELSTROM is a satirical contained thriller that takes the idea that the weather has the power to negatively affect our behaviour and amplifies it to 11. But what if we took it one step further still? What if it only affected male behaviour? And what if the affected men’s behaviour sorta, kinda, a teeny bit mirrored the behaviour displayed by asshole men the world over, resulting in a social commentary that explored themes of self-love and emotional independence in a battle royale of the sexes? Welcome… to MAELSTROM.

Writer: Stephen Thomas Parker

Details: 95 pages

It’s here!

After three months of non-stop writing and 300 entries, six of which were chosen for the High Concept Showdown, you guys voted Maelstrom the winner. I was happy to see Stephen Parker get the win because he’s been a LONGTIME reader of the site and the championship belt couldn’t have gone to a nicer guy.

However, you guys know how it is with me.

I don’t give free passes to anyone. If I’m going to give your script a ‘worth the read’ or higher, it’s got to be good. And thusly, the High Concept Showdown Winning Script Review begins!!!

After a fun opening scene where an old man turns into a psychopath who attacks his wheelchair-bound wife, we meet married couple Ash and Beth, who are escaping the city to experience a little R&R for the weekend. Well, that’s what Asshole Ash believes, anyway. In reality, Beth hasn’t told Ash that she’s taking him to… duh duh DUHHHHH – COUPLES THERAPY!

After they get to the therapy grounds and Ash yells at Beth for tricking him, we meet the rest of the couples. The retreat is led by 50-somethings Donna and Jean-Pierre. There’s Eleanor and Colin, who are so tied to the hip they complete each other’s sentences. We have masculine Christina and her beta husband, Brandon. We have Monique, who always puts her husband, Devon, in his place. As well as a few other couples.

Mere seconds after everyone introduces themselves, a storm rolls in, and with it, some sort of agent that turns men ——- CRAAAAAAAZY!!!! Instantly, the men begin trying to kill the women. Beth and every other woman who manages to survive charge into the mansion and slam the door behind them.

As the women try and grasp what’s happening, the men attempt to get inside, climbing up the side of the house to get in the windows. That’s when staff member and certified badass Chen arrives with a gun and starts shooting men dead!!! Unlike these women, who all have attachments to these rabid killers, Chen has no one. And that makes her a mean killing machine.

Believe it or not, it’s Beth who argues that Chen – and everyone else for that matter – needs to calm down and figure this out. If the men are under a spell, that means the spell can be broken and they’ll get their husbands back. But when the men go into full-on attack mode, Beth loses her sister soldiers, who confirm their belief that the only way out of this clusterfuck is to kill all men!

Normally, after I finish an Amateur Friday winning script, I don’t want to know what anybody thought because I don’t want those thoughts to influence my own review. But the second I finished Maelstrom, I went right over to the High Concept Showdown comments because I had to see what people thought of this script.

But, before we get to that, let’s talk about what worked here. My favorite part of this script, by far, was the first 20 pages. Stephen did an amazing job setting up the story and the characters.

After a fun teaser, he did a great job with the first scene, which has Beth and Ash driving to the marriage counseling retreat. Whenever I encounter a familiar scenario in a script, I’m looking for whether the writer is going to approach it the same way everyone else does or find a new angle.

A married couple going to counseling is a common scenario. I’ve read it in dozens, if not hundreds of, scripts before. Usually, the scene is written with a lot of tension in the air. You can feel that there’s something broken in the marriage. And while it’s an effective way to set broken couples up, it’s the same scene every time.

What Stephen did, instead, was clever. He made it so that Beth hadn’t told Ash they were going here. She’d tricked him into believing they were going on a weekend getaway. Then, Stephen informed the audience of that piece of information before Ash was looped in. All after setting Ash up as the world’s biggest asshole. What this did was create a dramatically ironic scenario by which we’re dreading the moment that Ash realizes they’re on a marriage counseling retreat. We know he’s going to go apeshit. Yet, we have to see what happens when he finds out so we keep reading.

Not only did Stephen give us a fresh angle with this setup, he created a situation that hooked the reader, forcing them to continue on to see what happened next. Brilliant.

The next big sequence is the introduction of all the couples at the retreat. I’ve been encountering this strange new trend whereby writers barely introduce characters. They’ll say something like, “Long brown hair and stocky.” Something that gives zero insight into the character. They’ll then follow that up by NOT giving the character an introductory action. Introductory actions are what allow us to remember characters. If you introduce someone yelling meanly at someone else, we’re going to remember them as a meanie. If, however, you introduce someone and don’t have them do or say anything, they are instantly forgettable. And yet so many writers do this.

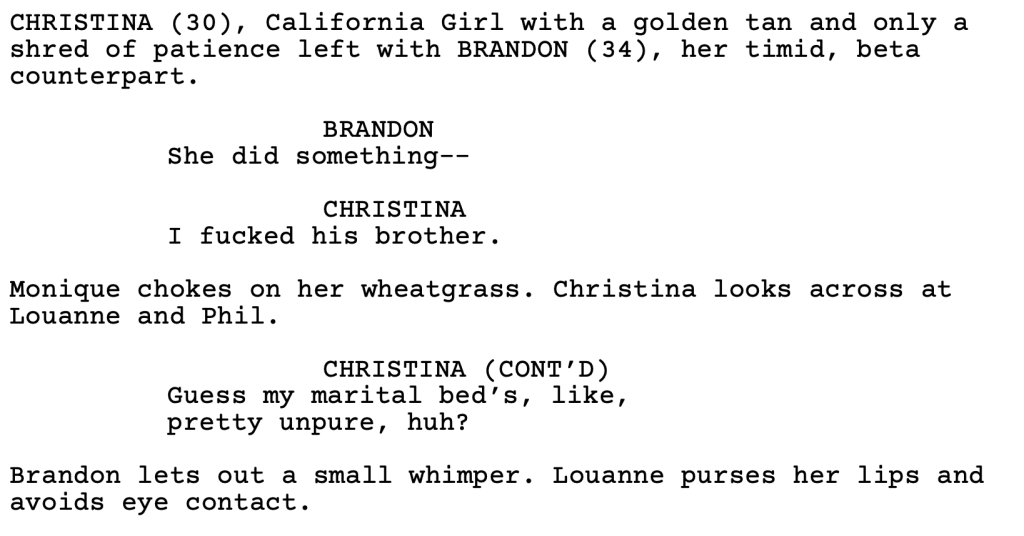

Here’s how Parker introduces one of the couples.

You’ll notice that, even though the character descriptions are short, they’re informative. We instantly get a feel for this couple. That’s followed with actions from both characters that reinforce those descriptions and, as a result, cement the characters in our head. Stephen did a great job with all the characters in that regard.

And then our movie takes a sharp turn. The storm moves in and all the men become psychopaths. The shift is so severe that it literally feels like someone picked us up out of one theater and dropped us down into an adjacent one. It’s pure crazed violence to the extreme. And I’m not sure I ever recovered from that.

The beginning of the script felt so thoughtful. I could feel the writer meticulously setting everything up. Then it’s, “AHHHHHHHH!!” “BANG BANG!” “STRANGULATION!” “KNIFE TO CHEST!” Over and over and over again. When action gets repetitive – no matter how intense or fun or exciting that action is – returns begin to diminish. And returns were diminishing quickly. Within ten pages of being inside the mansion, I was already exhausted.

But I hadn’t give up on the script yet. That would happen on page 33. This is when we learn that there’s a man in the house somewhere. Now, on the surface, this is a good idea. There’s a man on the loose somewhere, hiding in the house. Not only does that create tension and suspense, but it changes things up a little. We finally get a break from the crazed violence. And yet, something about it didn’t work for me and I couldn’t figure out what it was.

It was only once I read Brenkilco’s comment that it became clear. He pointed out that Stephen had established that this disease turned everyone into manic crazed psychos. Why, then, has one of them turned into a careful plotting stalker? Out of nowhere, the rules had changed. And in a movie like this where you’re asking the audience to buy into a pretty out-there concept, it’s imperative that the rules behind that concept be consistent. Once you break a rule, it now feels like the writer is making things up as they go along.

Which is the whole reason that I liked the beginning of the script. It was so well planned out. You could tell that Stephen had a reason behind every choice he made. That seemed to disappear once the storm hit. And, unfortunately, the script never recovered after that.

I’m not quite sure what advice I’d give to Stephen on this script. The central problem – the outrageous repetitive action – is a big enough issue that a lot of this script would need to be rewritten. And, unfortunately, I don’t know what I’d put in its place. Maybe you guys have some ideas. I’d be curious to hear them.

Oh, and one last thing. I want to give Stephen props for this line, which made me laugh out loud: “And suddenly, this fight looks very different… because Beth’s on the attack and hell hath no fury like a woman whose husband googled his wedding vows!”

Script link: Maelstrom

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You get one moment in your script where everyone’s running around like chickens with their heads cut off. Otherwise, you need structure to your set-pieces. What does ‘structure’ look like in a set piece? Check out the final backyard party in Parasite. Check out the trash compactor scene or the trench run in Star Wars. The talk show in Joker. The dueling ferry boats in The Dark Knight. The Pamela Anderson book signing kidnapping in Borat. You need a clear directive. Physical boundaries. A set of rules the audience understands so they can participate. And, finally, a little imagination to make the scene fun. Randomness is okay once. But if it’s the primary formula for your movie’s action, the movie’s going to feel messy.

You know how it works. Lots of people fought to be included in High Concept Showdown. Hundreds didn’t make it. Shall those writers go on for the rest of their lives never knowing why they weren’t chosen? NOT HERE ON SCRIPTSHADOW! We’re taking five submissions that didn’t make it and explaining why. Hopefully, you can use this information to improve your next submission. Let’s begin!

Title: Call of Judy

Genre: An eye-popping Action Adventure with real heart

Logline: When a kid wins First Play of a Next-Gen VR-Experience but gets lost in its digital limbo, his technophobe Mom must complete four bespoke games they were due to play together to find him.

Why You Should Read: This idea came to me fully formed. My son plays Xbox for hours (and hours), especially since lockdown, and he’s monosyllabic while online.

I’ve been known to play Call of Duty or GTA but my wife hates it ALL so I wrote it through her eyes.

Judy experiences the jolts her son gets from playing Xbox – but amplified massively. These two player games were created for Judy and her son, from a psych quiz but her son filled hers in so everything is askew.

Being it fully immersive VR, Judy’s inside each game, so those jolts are super visceral. And by playing 4 games, it opens up contrasting worlds of eye candy.

There’s endless fun riffing of several game genres but the search for her son packs an emotional punch that hits hardest.

Analysis: I occasionally see people play with the genre label, like David’s entry does. While this can be fun for the writer, in my experience, it indicates a bad script is coming. This goes back to the age-old notion that good writers don’t need bells and whistles. They don’t need a big crazy font for the title of their script. They don’t need to write a bunch of asides to the reader. They don’t need to invent their own genre. All they care about is telling a good story. To that end, one genre is preferable. You can get away with two (Comedy/Horror). But you should probably stop there.

As for the logline itself, I’m not up to date on video game lingo. So when I see “First Play,” capitalized, I’m not sure what it’s supposed to mean. Is that a game? Or is it a known term in the gaming world. “He got First Play of Red Redemption 2.” Capitalized words that aren’t typically capitalized tend to confuse me.

I’m into VR stuff so I liked that. I’m not sure I like the phrase “digital limbo.” It’s a murky way of saying what you’re trying to say, which is that he gets lost in the game. You don’t want any haze hovering over your logline. You want to make it as easy to understand as possible. I like that his mom is a technophobe. Some nice irony there. “Bespoke” is an odd word in this context and took me a minute to figure out. Anything that slows down a logline is a bad thing. And, finally, the central task itself isn’t very interesting. Based on what you’ve told us, the mom is going to be sitting in front of a TV playing video games for the 2 hour running time. Is that the movie?

This logline is a good example of how important each word and phrase in a logline is. The wrong word can send the reader off in a completely different direction than what you intended. I would encourage David to focus on clarity in the next go-around.

Title: Viewers

Genre: Sci-fi thriller.

Logline: After the CIA remote-viewer(psychic) program is dissolved due to a mission gone awry, an ex-member of the force comes across information about a Russian spy recruiting retirees. With nothing to lose, he puts together a rag-tag team to help hunt down the spy and prove to his previous employers that his best days are still ahead of him.

Why You Should Read: None

Analysis: The first thing I notice about this logline is that it’s long. A long logline does not mean the logline will be bad. But the more seasoned a writer gets, the better they get at writing loglines, and one of the things they learn to do is to keep the logline tight. Again, this isn’t a logline killer. It’s just a little red flag. “After the CIA remote-viewer (psychic) program is dissolved…” Okay, this is a red flag. Putting something in parenthesis is a major no-no in loglines. Also, the word ‘psychic’ seems to be an important detail. So why you’d relegate it to parenthesis, I’m not sure. From there, we get a lot of common logline words and phrasing. “Ex-member of the force,” “Russian spy,” “rag-tag team,” “hunt down,” “that his best days are still ahead of him.” I know this is hard, guys. You’ve got this very tiny amount of space to convey all this important information and the majority of those words are going to be common ones. But that’s why you need to make the key moments in the logline stand out. You need key specific phrases (“dream heist” from Inception, for example) that differentiate your idea from everything else. Without any differentiating elements, it’s just a bunch of words we’ve already seen before.

Title: The Bone Butcher’s Cosmic Slaughterhouse

Genre: Sci-fi/Horror

Logline: A couple of ex-addict, rock star has-beens discover an extraterrestrial portal allowing them to relive past moments and change their greatest regrets, but the new choices they make and a nasty creature threatens to make them pay for it with their blood.

Why You Should Read: This is not a wacky idea by an undisciplined writer! I have to say that right off the bat. The script started off as trying to be a very disciplined, marketable “It Follows” meets “Alien” with a kick-ass, high-concept engine. Well… that engine took over and renamed the script. Upon finishing an early draft, I was sure the story was too ambitious. Ex-addict, deeply flawed protags, fantastical, outer space set pieces, awesome creature designs, too much blood, cosmic music concepts (Don’t worry it’s not a musical!), and people willingly getting gruesomely torn apart by a black hole.

Yet then somehow, this script became a finalist in a couple sci-fi and horror contests as well as taking 2nd place in one. And my cynical writing group actually liked it. So I kept tinkering and polishing and getting feedback. Growing this thing like a cosmic chia pet for this very moment. I truly appreciate this opportunity and would relish in even the smallest amount of that amazing Scriptshadow feedback I’ve read over the years. Fingers crossed.

Analysis: While I wouldn’t call this an “everything and the kitchen sink” logline, I might call it an “everything and the slightly smaller bathroom sink” logline. Let’s go through it piece by piece. “A couple of ex-addict, rock star has-beens…”. So far, so good. I have a good feel for these characters. The ‘ex-addict’ feels organic to their old job, so it’s not just thrown in there to make the characters sound more interesting (something I encounter a lot in loglines). “… discover an extraterrestrial portal…”. Okay, we’ve just taken a huge leap. Whenever I see “portals,” I know there’s potential for the story to go sideways. I’ve read all the portal scripts, guys. It seems to be permission for a lot of writers to go to Wackyville. So, now, I’m on guard.

“…allowing them to relive past moments and change their greatest regrets…”. Okay, you’ve officially lost me. I distinctly remember having to read this part of the logline three times. It’s not written as elegantly as it could be. Also, it never works in loglines (or in scripts, for that matter) when there’s more than one objective. “They need to do this AND this.” You want a clean narrative. That means ONE thing. In Jaws, they’re not trying to kill a shark AND fix a broken dam. They’re just trying to kill the shark. “…but the new choices they make and a nasty creature…” At this point, there’s nothing that the logline could’ve done to reel me back in. But adding a creature to the mix definitely made things worse. It just feels like there’s too much going on at this point.

The good news is, people helped with this logline in the comments. And this is the new one they came up with: “A downtrodden couple, drowning in regrets, discover an extraterrestrial portal that allows them to change their past sins, but unwittingly unleash the portal’s blood-thirsty gatekeeper.” This logline is WAY better and shows you what a difference a well-written logline can make over a badly written logline. Which is why you should get a logline consultation from me! (E-mail carsonreeves1@gmail.com with subject line: “Logline Consult.”). Would this new logline have gotten the script into the High Concept Showdown? Probably not. But while I’d say the first logline put the script in the top 60 percentile, this new logline put it in the top 10 percentile. That’s a huge jump.

Title: High School Samurai

Genre: Martial Arts/Action

Logline: When a bullied, high school delinquent discovers that his local kendo dojo is a secret base for teenage samurai, he must fight with them to protect his family and the city of LA from an invading army of yōkai.

Why You Should Read: Yōkai are demons, ghosts and monsters of Japanese folklore. There are many tales of these creatures terrorizing the people of Japan during the feudal era, and even more tales of the brave samurai who faced them in battle. This script is one such tale, set in modern time where the yōkai have expanded their terror to the American west coast, and it’s up to the worst possible samurai to stop them; a troubled youth who lacks honor, loyalty and discipline. He must learn these values if he’s to protect those he loves, all while navigating the other great terror that is high school.

With splashes of Buffy, Kill Bill and Ninja Turtles, as well as the writing essentials like GSU and great characters, this is the kind of popcorn movie you’d enjoy with your best friends on a Saturday night at the local cinema. So kick back, play some koto music, and forget the worries of the world. This is “High School Samurai,” and I hope you enjoy it. Arigato!

Analysis: This one got some love in the comments. I love the title, “High School Samurai.” It rolls off the tongue. But when I got to his dojo being “a secret base for teenage samurai,” that’s a moment where you either buy in or step back. And I stepped back. I’m not sure why. It might be a preference thing – that pesky “personal taste” that gets in the way of so many great loglines. But I tried to imagine a bunch of teenaged samurai in my head and my head wasn’t cooperating with that image.

With that said, it was a big enough idea to still be in the running, which leads us to the second half of the logline, which ends with the words, “an invading army of yōkai.” I don’t know what yokai are. And that’s the thing with loglines. If the reader is on the fence, one wrong step can be the finishing blow. Now, astute readers of the site will point out that, in the very first sentence of the “Why You Should Read” section, the writer explains what yōkai are. But here’s the thing. Cause I remember this exact moment. I had a few hundred of these things to get through so I had to move fast. As soon as the nail was placed in the coffin, I was on to the next one. And this situation is not unique to me by any means. Nobody has time. Everyone’s moving on as quickly as possible. Now, do I think this logline is something the writer shouldn’t pursue? I wouldn’t go that far. People in the comments liked this so there’s obviously something to it. For my own taste, however, it wasn’t for me.

Title: KINGDOM COME

Genre: Sci-Fi Action

Logline: When a determined fleet admiral plans to ambush insurgent forces at a deep-space military base-planet, the base’s mechanic steps up to lead ground operations on the planet’s surface, and must step in when her admiral mother decides to take out the insurgency by any means necessary.

Why You Should Read: As a sci-fi fan, I’ve often thought about how galactic empires could manage to oversee bases and colonies spread across entire star systems. How likely is it that soldiers and other staff stationed at a base will be ready to fight, or even want to fight, a war they’ve been waiting years, maybe even decades to participate in? When they call, who responds? KINGDOM COME follows one individual who steps up when nobody else will, and she doesn’t stop until the job gets done, no matter where it takes her. You might know me in the Scriptshadow comments as CCM30. I’ve read and critiqued many scripts in this community over the years, and now it is my pleasure to offer up a work of my own.

Analysis: There were a couple of things working against this entry. For starters, this is a big science-fiction movie. Big science-fiction movies cost lots of money to produce. So, already, you’re at a disadvantage. When studios do make these movies, they hedge their bets on pre-existing intellectual property. If Warner Brothers is given the choice to spend 200 million dollars on a Dune movie or 200 million dollars on an original movie called, “The Divinity of Zal’Nahr” which one do you think is the more financially responsible choice. The reason it’s so important to internalize this is because it’s a question that filters all the way down the pyramid to the tiniest movies that the industry makes. If you’re a production company with a million dollars to spend, do you spend it making a horror movie or a drama? If you want to stay in business, it’s a horror movie. So you need to be thinking about your potential buyers when you’re coming up with an idea.

With that said, there is a caveat. And that caveat works like this. The more expensive a movie is, the better the idea has to be. Now, of course, “better” is subjective in a lot of ways. But one metric you can tap into is the ‘originality quotient.’ If the logline consists of a lot of generic words or things we’ve seen in other movies, it’s easier for the reader to say ‘no.’ Look at all the key words in this logline. “Fleet,” “admiral,” “ambush,” “insurgent,” “deep-space,” “military base,” “mechanic,” “ground operations,” “admiral mother,” “insurgency.” There isn’t a single unique word in the bunch. It’s all basic stuff. This results in a logline that doesn’t have the “flash factor.” Because the words are so generic, we imagine a generic movie. That’s why I didn’t pick this logline.

It’s a busy day today so I don’t have time to read a script. But I want you to keep your eyes on the prize – Comedy Showdown. My goal is to help sell the comedy script that wins it all. And, if that’s going to happen, you have to start with a strong concept. Without a strong concept, there is literally nothing you can write that will matter. It will be a great big waste of time.

So, how are we going to find this great concept?

Well, I watched Coming 2 America this weekend. The movie isn’t bad. But it’s not very good either. Eddie Murphy is doing the same thing Adam Sandler does with his Netflix movies. Playing it safe. Pulling the comedy wagon right down the middle of the road. Every once in a while (sometimes a long while), there’s a lol moment.

Despite Coming 2 America being average, there is something we can learn from it. Coming to America and Coming 2 America are two movies that base their concept around one of the oldest comedy setups in the book: Fish out of Water. The reason Fish out of Water setups work is because there’s usually a ton of comedy to mine from a person being placed in unfamiliar territory. In Coming to America, it was an African king experiencing New York City for the first time. And in Coming 2 America, it was a Queens kid coming to an African nation for the first time. In both instances, the jokes came from the lack of familiarity with their new surroundings.

While Fish Out of Water scenarios may have had their heyday in the 1980s, they’ve still proven a viable setup for Hollywood. We’ve had “Elf,” “Enchanted,” “Cedar Rapids,” “Thor,” “Borat,” and, most recently, “Wonder Woman 1984.” There’s something organically funny about placing someone in the complete opposite environment than what they’re used to. That creates conflict. And conflict is where a lot of comedy comes from.

That’s extremely important so let me repeat that. CONFLICT is where a lot of comedy comes from. Two people disagreeing (conflict) can give you a lot of funny dialogue. It’s why they release movies where the entire premise is two people who don’t get along (Rush Hour). But conflict isn’t just about interaction. Conflict is anything that bumps up against your character. If a bank robber is running from the cops and jumps in his shitty old Corolla, you can create a full-on comedy scene from him not being able to start the car. That’s the CONFLICT. The car refuses to do what it’s supposed to do.

This is a nice segue to my next point because there’s actually a close cousin to Fish out of Water, which I call, “Frog out of Water.” This is when you place a character in any situation that they are uncomfortable with. The more uncomfortable, the better. This is the setup for tons of great comedies. It’s similar to Fish out of Water in that you’re putting your character in a new situation. But it’s not so extreme that you’re taking, say, an Eskimo and putting him in the middle of Los Angeles.

Look at Meet The Parents. You’re taking this guy and dropping him into his in-laws house, who he has to then impress enough that they will want him to marry their daughter. The writers make the dad extremely skeptical, which turns the weekend into a very uncomfortable situation. The 40 Year Old Virgin is another example. This geeky 40 year old dude who keeps to himself is forced onto the dating scene to try and get laid. That entire process is uncomfortable. Again, a great way to mine more laughs is to increase the lack of comfort. The more uncomfortable you can make it for your character, the funnier it’s going to be.

This is especially true with Action Comedies. You’re looking for setups that put your hero(es) in the most uncomfortable situation possible. Central Intelligence. The Spy Who Dumped Me. Game Night. Good Boys. The less capable they are of dealing with the situation, the better. That’s where the laughs are going to come.

And, remember. KEEP PITCHING YOUR CONCEPTS before you decide to write them. Pitch them here in the comments if you don’t have anyone to test them on. If people don’t laugh or aren’t getting excited about your idea, move on to the next one.

Genre: Serial Killer/Sci-Fi

Premise: A former music therapist is recruited to use a mysterious machine to dive into the memories of a serial killer on death row.

About: This is the writer’s SECOND time being on The Black List. The first time was with The Traveler.

Writer: Austin Everett

Details: 119 pages

Today, I am shocked.

I read this script, which I did not enjoy (for reasons I’ll get into soon).

And one of my premises was that the writer wasn’t ready to be on the Black List yet. But then I did a little googling and learned that I’d already reviewed a script from this writer. And that I gave the script an impressive!

So now I’m all turned around.

I don’t know how these two scripts came from the same writer. The only thing I can come up with is that, after the success of The Traveler, Everett dug this one out of the deep corners of his hard drive, back when he was still learning how to write.

Because the writing here is not on the same level as that script.

What was my big issue with Earworm?

It comes down to most frequent advice I give writers who send me screenplays. Which is: TOO COMPLEX. MAKE IT SIMPLER.

Today’s script is so much more complex than it needs to be.

Let me go through a list of things we have to keep track of in Earworm.

A psychic

Who’s not really a psychic, but a psychologist

Who’s a certain kind of psychologist that specializes in music therapy

She’s been trying to adopt a girl for three years

She herself was adopted

She had a twin that disappeared when she was young

We have a serial killer

He’s in a psyche ward despite his killing rampage continuing

This killer was also an orphan

This killer’s parents committed a murder suicide

This killer’s foster parents also committed a murder suicide

This killer had a twin.

Nobody knew the twin existed until today

This twin was killed when he was younger

An administrator at the ward has found a new technology that lets you see into someone’s memories

Nobody knows how the technology works

Music sometimes helps the technology work

You can see into a person’s memories when you’re hooked up together

You can also see into a person’s memories when you’re nowhere near each other.

People think you have to be a twin to do the memory invasion.

Sometimes you can switch bodies with the person whose memories you’re looking into

Do I need to go on?

There are, like, 15,000 things going on here.

The script is about a female psychic, Kimball, who’s recruited by this guy, Judd, who works at a psyche ward. That ward is housing a serial killer named Lenny, who’s pled insanity for his case. Judd seeks out Kimball and asks her to come by. He hooks her up to a device where she finds herself inside Lenny’s memory. Specifically, a memory of one of the women he’s killed.

Just out of curiosity, Lenny’s logged thousands upon thousands of hours in life. Why isn’t the random memory Kimball jumps into something more mundane such as Lenny watching TV? Why is it whenever we jump into Lenny’s memory, it’s always one of his most important memories of his life? I’m not even going to try to explain that because I’m still trying to figure out how you hook someone up to a device and they randomly are able to access some serial killer’s memory who’s nowhere near them.

We learn some key details about Kimball and Lenny. Kimball had a twin sister who was taken one night. Lenny had a twin brother who died in a horrible accident. All of this is to imply that the reason Kimball can connect with Lenny on the memory machine that nobody understands is because they’re both twins. Or, I mean, they both have dead twins in their life.

I mean… am I overstating the complexity here?

First off, twin stuff is really hard to get right. If screenwriting were divided into 12 grades, twins would be the thing that everybody in the first grade used. It’s that cheap easy low hanging fruit that seems really juicy when you’re squeezing it in your hand. But all those juices do is make your script wet and soggy.

That’s not to say you can never use it. I have this twin idea that I’ve wanted to do forever. But you have to understand that most people think of twins as a cheap trick. So what you have to do is use that expectation against them. Do something early on with the twins that’s sophisticated that the reader didn’t see coming. This sets the tone for a more sophisticated story. Which you need to live up to for the remaining 70 pages.

The way twins are used here is the worst way you can use them. The twin stuff in Earworm is messy. It’s unclear. There are multiple twins, which is just compounding an already juvenile choice. The mystery memory device only works for twins. Dueling twin mystery backstories.

Random thought. Share your favorite ‘twin’ movie in the comments section.

But the twin stuff isn’t even the main problem here. The main problem is that there’s way too much going on. Just the fact that we start off meeting our protagonist as a psychic. And, then, we learn that they’re a special type of psychic that works with music therapy. And then we learn that they’re not really a psychic but rather a psychologist that lost their license. So this person is three different things within the first ten pages.

How bout we start with being one thing?

I get that, as writers, we want to change things up. But if that means throwing everything and the kitchen sink into a character, that’s worse than being too cliche. When I see something like that early on in a script, I say to myself, “This is too complex.” And what always happens is that ends up being a precursor for what to expect in the rest of the script. And what did we get for the rest of this script? Serial killers, twins, memory infiltrating devices without rules, multiple twin backstory disappearances and accidents, body-switching.

It’s a great big Sloppy Joe.

There aren’t any rules here. When you’re dealing with something as fluid and complicated as memory, you need to establish a set of rules that the audience understands. The Matrix painstakingly laid out every single rule of the Matrix. You can make an argument that it took too long to do so. But the reason they did that was SO YOU COULD ENJOY THE MOVIE. When you don’t convey the rules of the game, you’re going to have people in the back asking, “Wait, what’s a third down exactly?” Of course they’re not going to enjoy it.

The next person who writes a movie about memory needs to put a lot more effort into it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I want to speak to the future screenwriters here who want to write this type of concept. I read a lot of scripts that have to do with going into someone’s memories. Or going into someone else’s head. Before you write one of these scripts, do three full months of research where you learn the science behind the human brain, where you learn about memory, where you learn about the current technology being used to access and study memory. Get a doctorate in those departments. Because one of the things that destroys these scripts is the writer clearly knows so little about the world they’re writing in. When you do the research, you’re able to talk about things and present things in a manner that is believable. Even if these technologies haven’t been invented yet. But if all you’re doing is a few days of googling, the reader will feel that. They’ll sense the lack of authenticity in your story. You need to be an expert on whatever the subject matter is in your script. Period. If your plan is to half-ass the research, I can save you a lot of time. Don’t write the script.