Genre: Con

Premise: (from Black List) A chain of scam artists goes after one wealthy family with the perfect plan to drain them of their funds. But when love, heartbreak, and jealousy slither their way into the grand scheme, it becomes unclear whether the criminals are conning or the ones being conned.

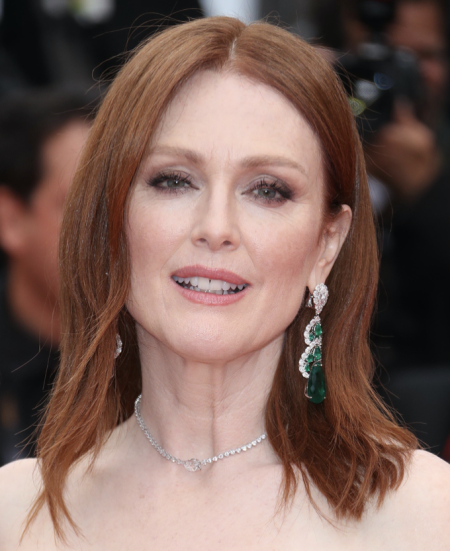

About: Oddly, this comes from the team whose only other feature credit is the wacky Jonah Hill comedy, The Sitter. It finished top 10 on the 2020 Black List. Apple and A24 snatched the spec script up when it went up for auction. Julianne Moore will play Madeline.

Writers: Brian Gatewood and Alessandro Tanaka

Details: 117 pages

This genre has disappeared as of late and I’m trying to figure out why.

It could be as simple as nobody’s written a good con-man script in a couple of decades. I’m trying to remember the last one they released. Was it that Will Smith Amber Heard abomination? The box office results of that one probably didn’t help any subsequent con man movies get made.

I think the issue is that when you write one of these, they can’t just be “movie smart.” It’s one of the few genres where the writer has to be a lot more intelligent than the audience. Because if they aren’t, the cons aren’t clever. And if the cons aren’t clever in a con-man script, then what are we even doing?

Most of the cons in these scripts are “movie-clever.” You know how you’ll watch a movie and there’s a party scene and one of the characters will make a joke and everyone in the scene will laugh but nobody in the audience will laugh? That’s a “movie-joke.” It doesn’t make real people laugh. Same problem with bad con-man scripts. The cons work on the movie characters but the audience wasn’t fooled at all.

I’m hoping this is one of those rare con-man scripts where I’m genuinely outsmarted. Let’s see.

20-something Tom is living a pretty lonely life in Philadelphia when we meet him. It doesn’t help that he owns a bookstore that has no customers. Luckily, that changes when 20-something cutie pie Sandra shows up. Sandra is looking for a book for school and just as Tom is about to ring her up, he does something he never does – he asks her out to dinner.

The two have a great first date, then a great second date, and after a couple of weeks, they’re spending every second together. Tom is on cloud nine! That is until one morning at Sandra’s place when some guy shows up yelling at Sandra. She tells him to leave and explains to Tom that that was her brother. He owes a lot of money to some bad people. How much, Tom asks. 350,000 dollars.

Despite us screaming through the screen at Tom to NOT DO IT, Tom gives her the money (it turns out Tom was secretly rich). And then, magically, the next day, Sandra no longer lives in her apartment. She’s gone.

We then cut back in time to meet… Sandra. But this Sandra is much different than the previous Sandra. She’s a hooker-junkie. Pissed at the lack of money Sandra is making, her pimp makes her approach some lonely guy at the bar. This is Max. Max is in his 30s and can best be described as neutral. After some small talk, Max informs Sandra that he’s going to take her away from this life and help her find a better one.

Cut to our “Neo training sequence” where Max teaches Sandra how to be a lady. He teaches her to sound like she knows about things she doesn’t. And, most importantly, he teaches her to find and play a mark. Pretty soon, Sandra is ready to be a real live con woman.

Then we cut back even further in time to meet… Max. It turns out Max is a screw-up who constantly crawls back home for money. Even his own single mom, Madeline, is embarrassed for him. And this is the worst time for Max to be asking for money since his mom has finally found someone she likes – Richard. Richard is handsome and successful and a genuinely good person. Please, his mother tells Max, don’t screw this up for me.

But what if I told you Max couldn’t screw it up for his mom. That’s because, this isn’t really his mom! It’s his mentor! The person who taught him how to con! And they’re lovers now. Or, at least, Max believers they’re lovers. His fake mom may very well be taking Max for a ride. But that’s okay. Because Max has just found out something very important about Richard. That his son owns a bookstore in Philadelphia. That’s right… Richard’s son is Tom! Duh-duh-duhhhhhhhh!

The dead horse I beat over and over again on this site is: FIND. AN. ANGLE. Find an angle. There are lots of ways to tell a story. You can, of course, use the tried-and-true “straightforward” approach. No gimmicks. No games. A simple linear narrative approach. And that’ll work if the idea is really strong. But sometimes you need a snazzier approach.

That’s what we got today. Telling this story in reverse order while switching the central character each time was genius. Like I said at the beginning of this review, the con-man genre is inherently predictable. So if you tell it in a linear fashion, it’s too easy to guess what’ll happen. The very nature of us changing perspectives and times every 20 pages eliminated our power of prediction. Cause I didn’t even know where the story was headed, much less who was conning who.

But the writers didn’t stop there. They knew that for any screenplay to work, it has to connect with the reader on an emotional level. There are a handful of emotions to choose from. Here, they use anger. The manner in which Sandra took advantage of Tom was so cruel that we wanted to see her go down. So the writer wisely made that the final storyline.

It turns out that Madeline screwed Max over because what she was really interested in was getting Richard’s money when he died (he was in poor health). So the story picks up at the wake, with Tom meeting Madeline as the lawyer informs them that Tom’s father left all of the money to Madeline (in part because Tom proved he wasn’t financially responsible after being conned out of 350 grand). Madeline is elated, of course. But what she doesn’t know is that Tom has spent the last couple of years looking for the woman who conned him. And he’s finally found her. Of course, wherever Sandra is, her connection to Max won’t be far behind. And guess who’s connected to Max? Madeline.

So it isn’t just about the cons here. It’s about the emotional payoff. Do we get to see what we really want to see – which is for these three people who took advantage of Tom to go down. And that, my friends, is how you write a good screenplay.

A side note here is that the dialogue was only slightly better than average. However, I think that’s why it worked. A lot of times in this genre, the writers try to show off their dialogue. Everybody’s got a clever comeback. People are using double-entendres. A lot of the dialogue is dripping with sexual innuendo. That’s fine if that’s the kind of story you’re writing. But these writers wanted this to feel realistic. If you want a story to feel realistic, you can’t over-stylize the dialogue. It’s got to feel authentic.

Which is a good reminder. Everybody talks about how important dialogue is. But if you’re not great at it, there are stories you can tell that don’t require you to be great. So just pick those stories.

My only problem with this script is the ending. I’m not going to go into specifics because it’s super-spoiler territory. But I think the writers bit off more than they could chew. The beauty of the first 90% of this screenplay was how simple it was. Yes, we kept changing times and characters, but once we got into a time-period, it was straightforward. The ending betrays that simplicity, which is unfortunate, because before that, this was a ‘mega-impressive.’ It was, honestly, almost perfect. Hopefully they clean the ending up before they shoot. Either way, this was still a really good script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure we know what’s at stake!! I find out AFTERWARDS that the Richard con was a half billion dollar con?? No no no no no no. That information needs to be clear BEFOREHAND. We, the reader, will be way more invested if we know that kind of money is at stake. Before that, I thought Richard maybe had 5 million dollars or something. I was like, good for you. You can get a three bedroom apartment in midtown. I didn’t realize how big this con actually was.

Is Karma the next Matrix, the next Wanted, or the next Assassins Creed?

Genre: Action/Supernatural

Premise: After an aimless woman wakes up from a short coma, she begins exhibiting special abilities.

About: David Guggenheim is one of those writers who experienced the screenwriting dream. It’s one thing to sell a script. A lot of writers have done that. But to get a script made into a movie is a rare thing. When Guggenheim sold his first script, Safe House, it just happened to be exactly what Universal Studios was looking to make at the time. So they fast-tracked it, and 8 months after Guggenheim sold his screenplay, his film was being made. That’s insane. And the thing is, when you get a produced credit from one of the big studios, you’re set for the next decade at least. And probably for life. Because writers who get stuff made are highly coveted. People think if they’ve done it before, they can do it again. So you’re going to keep getting work. Guggeneheim would eventually parlay his success into the show, Designated Survivor. On this one, he’s partnering with super-producer, Simon Kinberg.

Writer: David Guggenheim

Details: 128 pages

It’s the first spec sale of the year!

And if it’s going to be the first, it’s gotta be big! Big concept. Big page count. Big rating on Scriptshadow, though? Let’s find out.

Rachel is a 30 year old grade-school teacher who’s sleepwalking through life. It’s not that she isn’t motivated. But she has no direction. Her one love – painting – is something she happens to be terrible at. Her younger sister thinks she’s dying of boredom and wants Rachel to move to Chicago with her.

Meanwhile, we get a look at some Indiana Jones motherf#$%#r running through caves and throwing ancient daggers at people. This is Boone. Boone is a force to be reckoned with, according to Aegis International, a private security company that has dedicated all its resources to capturing Boone, something it’s been unable to do.

But that’s about to change. One day Rachel gets blindsided by a car, then a few days later wakes up in the hospital just as the doctor is trying to decide what to do with her. Rachel makes a suggestion, citing, word for word, an operating procedure from a 1915 English medical journal. Huh? How did she know that?

But that’s not all Rachel knows. A couple of days later, in the elevator, she has a fluent conversation in Arabic. But Rachel doesn’t know Arabic. Freaked out, Rachel heads home, only to have Aegis CEO John Gartner burst into her apartment with a team of men. He explains that she needs to come with them now! A minute later, a car BARRELS THROUGH THE WALL. It’s Boone! Who starts shooting at Rachel. Chaos ensues and Rachel flees!

John finds Rachel later and explains to her that she’s special. And if she wants to find out how special, she’ll come with him. He flies her to Aegis in France, where they begin the training sessions! You’re a “past-lifer” he explains to her. Someone with the ability to recall your past lives. This means that any skill anyone in your past lives had, you can obtain. “How?” She asks.

“Follow me.”

Rachel is placed in the “womb,” which allows her to be guided through an advanced form of regression therapy. Here, she can go directly into her past lives. And with every life she experiences, she retains their skills. Magician, samurai warrior, pianist, chess prodigy, you name it. Get in my way and I’ll check-mate yo a$$. Most past-lifers can only access up to 15 of their past lives. But Rachel is special. She completes 15 in her first day!

A newly energized Rachel is now ready to take on her nemesis – Boone. Aegis locates Boone hiding in Germany. So off they go. Oh, but if you think you know what’s going on, think again. When Rachel finally comes face-to-face with Boone, he tells her that it’s all a lie. That he isn’t the enemy. John Gartner is! Hmmm, is Boone just trying to protect himself? Or is he telling the truth? I know one thing’s for sure. Ya better protect your queen, b#$%h.

CHESS CHAMPION!

Okay, so let’s talk about this idea because it’s uncanny that I’m reading this after yesterday’s post about the next Amateur Showdown genre. For those who didn’t catch it, the next showdown is for HIGH CONCEPT scripts. “Karma” is the DEFINITION of a high concept. Here, the writer takes an idea that was accessible to everyone – past lives – and sexes it up. What if you could access those post lives? What if you could access the abilities of the people who lived those lives? You would be… superhuman. And just like that, you’ve got a high concept.

A common through-line with high concept ideas is that, when you hear them, you wonder why you didn’t come up with the idea yourself. We’ve all read that news story about the person who wakes up from a coma and all of a sudden starts talking fluently in a language they don’t know. Why didn’t we ask how to turn that into a movie? Guggenheim did, and he’s reaping the benefits.

It’s also an example of how to come up with a high-powered movie ready version of an idea as opposed to a boring variation of that idea. Cloud Atlas was also about past lives. But instead of packaging it in a cool action format, it expanded it out into a three hour drama. Which of these ideas do you think an audience is more interested in?

So Guggenheim gets an A+ in that department.

But I have the same issue with this script that I do with a lot of Guggenheim’s scripts. The execution is too by-the-book. I understand that these Matrixy concepts need to go a certain way. But if I’m predicting things that are happening 60 pages ahead of time, that means you’re not taking any chances. Don’t get me wrong. It’s still fun. But there’s a difference between those summer movies you see once then never watch again and the ones that you keep coming back to. The ones you keep coming back to are the ones where the writers took chances.

The writers and scripts I’m most impressed by are the ones where I’m reading them and thinking, “I could never do that.” I mentioned The Misery Index yesterday, a semi-finalist in my contest. When I read the dialogue in that script, I knew that if you put me in a library with all the greatest writers of all time teaching me how to write for 50 straight years, I still could not be able to write dialogue like that.

Yet, in Karma, I feel like the top 30% of writers here on Scriptshadow could write it just as well as Guggenheim. I’ll give you an example. One of the major components of this screenplay is the past lives. So the writer has to come up with all of Rachel’s past lives she’s lived. Here’s a sampling of what we get… Feudal Japan, Renaissance Painter, World War 2 pilot, Shaolin Monk, a blacksmith, ancient Egypt, Sherpa on Mount Everest, pre-historic man.

In other words, past lives that you could’ve come up with after literally 30 minutes of research. There’s nothing unique here that another writer wouldn’t have come up with. I want to stress that because it’s important. Your job as a writer is to come up with things that the rest of the world and your competition (other writers) couldn’t come up with. Or else why do we need you? If you’re giving us what we already thought of, well, that’s lame. We, the audience, are supposed to be creatively inept compared to you.

So that bothered me.

But mark this one down on the list of why concept is king. Even with its weaknesses, it still works, because the concept is so fun.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Often times, high concept is about taking a cool ‘what if’ scenario and placing it inside a high octane genre. Writers get this wrong all the time, so pay attention. Past lives is not a high concept idea on its own. It’s just as capable of being low concept in the wrong hands. You could write a movie about a guy who discovers he had a past life as a sheep farmer and becomes inspired to leave the city and live a self-sustainable life in Wyoming. You’ve technically got yourself a past lives script. But is it a good idea? To get the sexier logline, take your ‘what if’ scenario and plug into a bigger flashier genre, like Karma did (supernatural action). Big flashy genres include action, thriller, sci-fi, and horror. Those genres always make the idea feel bigger.

How to choose ideas that producers want to buy, next amateur showdown announcement, important end-of-contest dates, and the single worst screenwriting trope ever.

I remember being a young inexperienced screenwriter desperate to understand what it was Hollywood wanted. My thinking was, if I know what they want, I can give it to them. Which should be obvious. If your dream is to make food for McDonald’s and you’re determined to get poached salmon on the menu, chances are you’re not going to succeed. You gotta be the guy who comes up with the McGriddle.

Yet coming up with a script they’d be interested in still seemed difficult. Sure, you could write the next Tenet, but then everybody tells you it’s too expensive to make. You could write the next The Conjuring, but then everybody tells you they read ten Conjurings a month. We need something original. So then you write something original, like First Cow, and everybody tells you that nobody is going to make a movie about something that obscure.

So, what do you do???

I wish, back then, I could’ve engaged in the practice of what I’m doing with this contest – reading scripts with the explicit purpose of making movies from them. Because I’ll be honest with you. There are a LOT of good scripts in the finals. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really. Script after script, I’m impressed with what I’m reading. However, it’s so easy for me to decipher which scripts advance and which don’t. I simply ask the question: “Is this something I want to produce?” The second I ask that question, the answer of whether that script advances or not becomes clear.

So, as a writer, that’s where your head should be at when picking scripts to write. You want to ask the question, “Is this something someone would want to produce?” I understand that the answer to that question varies depending on who’s producing. But you can still get a sense of how difficult the path to victory is. If you’re writing a movie like David Lowery’s, “A Ghost Story,” for example, and getting butt-hurt that nobody wants anything to do with it, then you have to get real with yourself. Nobody ever makes that kind of movie unless the director wrote it.

I’ll give you an example. One of the best writers in the finals is David Burton. Here’s the logline for his script, “The Misery Index:” A terminally ill, improvident father spends the last day of his life touring NYC with his estranged daughter, and has only a few hours to right a lifetime of wrongs…and make 1.2 million dollars.

David is an extremely talented writer (his script made the Top 50 of the Nicholl competition). But as I’m reading the script, I’m imagining trying to sell this movie every step of the way – to production houses, to financiers, to distributors, and, ultimately, to you, the people who pay for it, and I’m thinking, “That’s going to be one long difficult journey. Even if I do everything perfect, it’s still going to be a hard sell.”

Let me make something clear: I’m not saying it couldn’t happen. I told David himself that it’s a juicy part for an actor. If you can get someone big to play the main role, the film could get financed. But when I compare it to, say, one of the scripts I read which I think could be the next Die Hard, the decision is easy. Every step of the way, it’s going to be people jumping over each other trying to get involved in that movie.

Look, I have my passion projects as well. Every director or producer has that idea they know isn’t designed to make money unless it’s perfect. But that’s kind of the point. People would rather play their own passion project lottery ticket than someone else’s. Which is why very few passion projects get through the system unless they’re directed by the directors who wrote them.

So while I know it isn’t the perfect way to decide what to write, it should be one of the tools you use to decide. Ask yourself, “Is this a concept that a producer – someone looking for something that has a good chance of moving through the system and getting made – would be interested in?” Because a common mistake screenwriters make is only looking at their screenplays as a writer. You should at least attempt to see what your project looks like through the eyes of those responsible for selling it.

Which segues perfectly into our next Amateur Showdown. Yes, that is right, we’ve got another Amateur Showdown on the horizon. Amateur Showdown has led to script sales, agents, managers, even movies getting made! So you bet your bottom dollar you’ll want to enter your latest script. What’s the genre going to be? Drumroll please……………………

Amateur Showdown Genre: HIGH CONCEPT

Where: Entries should be sent to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

What: Include title, genre, logline, why you think your script deserves a shot, and a PDF of your script!

Entries Due: Thursday, March 4, 6:00pm Pacific Time

I already know what you’re thinking. What does high concept mean, Carson??? High concept is an admittedly vague term so I’ll keep that in mind when I go through the entries. The basic idea is that it’s a movie concept, as Michael Bolton once famously stated, “with a big sexy hook.” A family that can’t make any noise or else they’ll be killed by monsters (A Quiet Place). A future where murderers are convicted before they’ve committed the act (Minority Report). A dinosaur island (Jurassic World). A man whose memory only goes back 8 minutes tries to solve his wife’s murder (Memento). A failed singer wakes up one day to learn the Beatles never existed and he’s the only person who remembers their songs (Yesterday). A high school girl and a serial killer switch bodies (Freaky). A woman is hunted down by her supposedly dead husband, who has figured out how to become invisible (The Invisible Man).

Not on any ‘high concept’ list would be movies like Ladybird, The Way Back, The Assistant, Moonlight, A Star is Born. I wouldn’t even consider Extraction high concept. A guy saving a kidnapped kid is far from a sexy hook. Ditto, John Wick. A hitman who comes out of retirement to kill a bunch of Russian mobsters is a very basic premise.

Character-driven ideas tend not to be high-concept. It’s sort of built into the term. A high-concept idea is going to be “concept” driven. Yes, there are a few examples of high-concept character-driven ideas. “Her” is one. A guy falls in love with his AI computer. That’s a character-driven hook. But this is kinda the business. Understanding big ideas that audiences would pay for is what separates the wheat from the chaff. So “getting it” is kinda the point.

Finally, an update on the contest. Here’s the plan. I’m going to announce the finalists on Friday. And because there were so many good scripts that didn’t make the finals for a variety of reasons, I’m going to review four ‘almost-made-it’ scripts next Monday-Thursday. And then, on that Friday, I will announce the winner of the contest.

If you’re someone in the industry looking for good material and good writers, you’re definitely going to want to mark these dates down. The level of writing in this contest is better than any contest I’ve ever done and it’s not even close. There was so much strong material. And I’m excited to introduce some of those writers to the world. So tune in Friday and all next week.

I can’t wait!!!

What I learned: I couldn’t leave this post without mentioning one more thing because it had such a huge effect on me this weekend. I single-handedly quit watching Your Honor due to the ASTHMA INHALER TROPE. The asthma inhaler trope is one of the single worst inventions in the history of storytelling. It has made its way all the way up to the “TOP 5 ANNOYING MOVIE CLICHES.” For those who haven’t seen the show, Brian Cranston’s character’s son has asthma. And an asthma inhaler. The actor who plays the son so overacts the asthma attacks that I turned the show off. I couldn’t do it anymore. They were that insanely annoying. I’m going to finish this off by making a plea to the screenwriting community to retire this trope. It is cliche. It is overdone. It is evil. And, worst of all, it’s unoriginal. Let 2021 be the death of asthma inhalers in screenwriting. Thank you.

“Carson,” some of you ask. “Why is it you like Cobra Kai so much? It barely adheres to the rules you preach and it’s one of the cheesiest shows on television!” I will agree with you on the second point. But the first point I’m going to push back on. Sure, Cobra Kai isn’t a university course in screenwriting awesomeness. But it does a lot of things right, which is why myself and so many other people are obsessed with it. So today, I’m going to share ten screenwriting lessons to take away from this season of Cobra Kai!

Goals, Goals, and more Goals! – Looking out at the landscape of a TV series can be daunting. 40-60 pages per episode. 10 episodes per season. 5-7 seasons. That can be as many as 4200 pages. How do you fill up all that time? There isn’t any one way. But goals help a lot. You set a goal for the key characters. They go off and either succeed or fail at that goal. And then you replace it with a new goal. For example, the season starts off with Johnny’s son, Robby, running away after putting Miguel in a coma during a fight. So Johnny and Daniel LaRusso go looking for him. That’s their goal. To find him. And when that goal is completed, their paths diverge and they each receive a new goal. Johnny tries to help hospital-bound Miguel walk again. And when Daniel’s car dealership is in danger of being bought by a Japanese company, Daniel heads to Japan to convince the company not to buy. TV character goals do not need to be wrapped up in a single episode. Depending on how big/important the goal is, it can last multiple episodes. Daniel’s trip to Japan lasts two episodes, for example. So whenever your TV show feels like it’s wandering, just add goals!

“You’ve got three minutes.” – It’s one of the oldest tricks in the book but it works like a charm. There’s something about a stated time limit in a scene that increases its intensity. Usually, when we talk about “urgency,” we do so in the context of the entire script. We add urgency (the “U” in “GSU”) to the hero’s journey. But you can do this in individual scenes as well. In a mid-season scene, Kreese (the big bad villain) approaches Johnny (the anti-hero) at a diner. Kreese wants to talk. Johnny doesn’t. Then a cop comes in behind Kreese, leans over the diner counter, and orders a sandwich to go. The cook says, “It’ll be ready in three minutes.” Johnny turns to Kreese. “You’ve got three minutes,” he says. And Kreese makes his case. This isn’t even an elegant way of using the rule. But the point is, it works. It gives the scene form and urgency. Contrast this with 75% of the scenes I read, which feel rudderless and never-ending. You can’t use this trick all the time or the reader picks up on it. But if you’re struggling with a scene, try it out. My guess is it will add a spark.

We’re going to need a bigger villain – Villains can often come off as one-dimensional. Mean for mean’s sake. And while in feature films, you’re often locked into that simplicity, you have more leniency in television, which has more time. Johnny started off as a villain in this franchise. And he occasionally dips back into that villainous role. But one of reasons we still root for Johnny is because there’s a bigger villain – Kreese. Kreese being cruel to Johnny makes Johnny sympathetic. This also happens with Hawk (the kid with the mohawk). Hawk is a big mean jerk and Kreese’s number 1 student. But then Kreese brings in new students, including a bigger meaner jerkier dude who always picks on Hawk at school. All of a sudden, Hawk doesn’t seem so bad. The act of bullying creates sympathy for the bullied party. Which is why, when you need to create sympathy for villains and anti-heroes, you just add a bigger villain.

Flip the Mentor script – In many movie and TV team-ups, there’s a mentor relationship. You have the older wiser mentor helping the younger inexperienced hero. But if you want to have some fun, especially in TV, you want the hero to occasionally teach the mentor. In Cobra Kai, Johnny is Miguel’s mentor. He helps him with karate and as well as regain his skills after his accident. But in episode 6, the technology-challenged Johnny is faced with a Facebook message from an old flame. Johnny’s first instinct is to write his life story back to her. But it’s Miguel who informs him that the move is suicidal, then helps Johnny write a proper response as well as improve his social media market value so he’ll look better for the girl.

Never use flashbacks… except in television! – You know how I feel about flashbacks. I hate them. However, with the extended length of a TV series (compared to a feature), flashbacks are more acceptable. But there’s a caveat to that. A flashback should never be used solely for exposition. It should be dramatic and entertaining in its own right. Kreese gets a lot of flashbacks in this season. The first of those shows him working at a restaurant as a teenager. The mistake would’ve been to have Kreese sitting with his high school sweetheart telling her all the things he wanted to do with his life (I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read a version of that scene). That’s dramatically uninteresting and the definition of straight exposition. Instead, they build the scene around a jock a-hole and his buddy giving Kreese a hard time (another “We’re going to need a bigger villain” moment!). The scene is entertaining in its own right due to the constant tension and conflict between Kreese and the jock. In the meantime, without even realizing it, we’re leaning about Kreese’s past. That’s how you do flashbacks.

Imply rather than tell – Miguel, our young hero who’s stuck in a hospital bed after waking up from his coma, can’t feel his legs. Now, sure, you can have a doctor come in and inform Miguel that, he’s sorry, but Miguel will never be able to walk again. But that’s “telling.” It’s more interesting if you “imply.” Miguel and his mother are talking. The doctor comes in. He does a couple of tests on Miguel’s legs. Then, the mother follows him out of the room, and Miguel sees them talking through the window. Whatever the doctor is saying is clearly devastating to the mother. That’s when we know, without any characters telling us, that Miguel won’t walk again.

Money makes the world (and storytelling) go round – Embrace money problems. It’s one of the best ways to motivate characters. Miguel’s surgery to fix his legs is going to cost a fortune. Johnny’s out of a job and running out of money for rent. Tory (one of the villains) is responsible for keeping a roof over her family’s head since her single mom is sick with cancer. The more people need money, the more desperate they get. And that’s where the drama comes from. Arguably the greatest TV show ever, Breaking Bad, is about a guy who has to make several million dollars before he dies of cancer to leave for his family.

Character Contrast for the win! – You should actively force your characters into places they don’t fit into. The rough-around-the-edges Johnny Lawrence meeting a couple of degenerates in a prison yard lacks contrast and therefore isn’t memorable. Meanwhile, a couple of Johnny’s funnier scenes occur when he goes to an upscale wellness center to visit his ex-wife. Or when he barges in on his old high school buddy turned priest while he’s giving a sermon. These scenes are both fun to write and fun to watch.

More characters means more potent scenes – Cobra Kai has a HUGE character count. One of the biggest I’ve seen. The reason you want a lot of characters in television is because the less scenes each character has, the more potent you can make those scenes. If you were to write a TV show with only two characters, imagine how much harder it becomes to write new scenes in episode 4, episode 8, season 3. Conversely, when each set of characters only has a few scenes per episode, you can pack a ton of of punch into those scenes. There are very few scenes in Cobra Kai that don’t have significant conflict or a high level of entertainment and that’s because the show only has to give each set of characters 4-5 scenes per episode. Of course, this is relative. If you have a great writer, a 10-episode season, and two extremely well written leads, like Breaking Bad, you can keep writing strong scenes for them indefinitely. But even Breaking Bad would occasionally cut away from Walter and Jesse.

Big Boss Payoff – There should never be a final fight with the boss character in film or television that doesn’t contain a payoff from earlier. In Cobra Kai, Daniel fights Kreese in the climax of the final episode. Kreese has him dead-to-rights until Daniel pulls off a “double paralysis” move he learned from his old nemesis, Chozen, who he saw during the Japan episodes. Chozen sparred with Daniel and used the paralysis move (hitting Daniel at certain pressure points on his body so that he couldn’t feel his arms or legs) that rendered him helpless. The big boss payoff is one of those things in screenwriting that’s almost impossible to mess up. In fact, there’s only one way. Not use it.

“Lakewood” may be the single most intense script I’ve ever read.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (me being deliberately vague cause I want you to read the script yourself) A school shooting told in a very unique way.

About: Man, Chris Sparling has come a long way. He started out placing a man in a coffin for 90 minutes. His latest movie, Greenland, is a studio disaster film. Now, he’s going back to his roots. “Lakewood” comes from the same production house, Limelight, that produced Scriptshadow Top 10 2020 film, “Palm Springs.” It stars Naomi Watts.

Writer: Chris Sparling

Details: 97 pages

(Scriptshadow Recommendation: Read this script before you read the plot synopsis! The power of this script is in its exciting plot developments)

The Obvious Angle.

Why is it every screenwriter’s worst enemy?

The Obvious Angle is the movie idea that approaches the subject matter just like everybody else would. If I told you to write a Western, the obvious angle is to have a mysterious no-name dude strut into town and start to stir up trouble. Borrrr-ing.

What makes or breaks a writer on the conceptual level is finding a fresh angle into well-explored subject matter.

And today’s script does that as well as any script I’ve ever read.

42 year-old widow, Amy, is going for her morning jog. This is the only time for Amy to clear her mind and alleviate some stress. Which she’s had a lot of lately. Her husband died two years ago in a car Amy was driving. And her kids – a daughter in elementary school and a son (Noah) in high school – are both still battling depression.

While on the outskirts of her town, Amy observes a strange sight. A couple of cop cars zoom along the road. It’s not something you typically see in this middle class suburb, but she doesn’t think much of it. Instead, she answers a couple of calls from her bougie friend, Heather, and her mom, who’s annoyed with Amy’s lack of communication.

And then Amy sees a couple of other cops zoom by. These with lights and sirens on full blast. This gets her attention. A quarter mile later, Amy receives a text: “THIS IS A CODE RED ALERT FROM THE LAKEWOOD SCHOOL DEPARTMENT. YOU WILL RECEIVE A RECORDED MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT WITH INFORMATION AND INSTRUCTIONS. DO NOT DISREGARD THIS CALL.”

The call comes in and a recording explains that “All Lakewood schools have been placed on lockdown due to an ongoing incident.” Amy immediately calls a teacher at her daughter’s elementary school. The teacher assures her that her daughter is okay. The problem, it turns out, is at the high school. The thought of something horrible happening at the high school is terrifying but luckily for Amy, her son, Noah, stayed home sick today.

At least, that’s what she thought. Amy calls Heather back since Heather has a daughter at the school, and learns that Noah did, indeed, go to school today. Amy hangs up and tries to call Noah, something she will attempt to do a lot over the next hour. But he’s not answering. So she decides to call the police. Except the police call her first. They want to know some information about Noah. “Why?” Amy asks. They refuse to say. Amy tells them everything she can, including one detail she’d forgotten until now, at least in how it relates to her son – tomorrow is the anniversary of her husband’s death.

During this time, Amy is desperately trying to get people to pick her up. But everybody’s already at the school, trying to figure out if their own kids are safe. So she calls an Uber. An Uber that’s going to be there in 5 minutes. Then 10 minutes. Then 15 minutes. Everything in town is being affected by the situation at the school. If Amy’s going to get there, she’s going to have to do it with her own two feet.

Amy is able to get in touch with an auto technician working on her car who happens to be right next to the high school. She orders the guy to go to the school to try and see if he can find her son. Within minutes, the technician tells her that the cops are towing away a car – HER SON’S CAR. Now Amy is really freaking out. As she continues her journey towards the school, she makes a series of frantic calls to try and figure out where her son is and what’s going on. Until finally, Noah answers… and she finds out the truth.

“Hey, Screenwriter A. I want to make a school shooting movie. Can you write it for me? Please come up with a good idea.” 999 out of 1000 screenwriters are going to come up with the Obvious Angle, which is something like this.

But Chris Sparling learned, early on, that it’s possible to tell stories in the unlikeliest of ways. And so he came up with a really cool angle for a school shooter movie. A school shooter movie told in real time through the point of view of a mother out in the middle of nowhere whose son may or may not be the school shooter.

That’s freaking genius.

Because think about it. When you put us in the school with the shooting, what kind of scenes are you going to get? Students pleading for their lives while an outcast kid in a black jacket shoots them dead? How many times have you seen that image before? A lot. Moments lose their dramatic impact the more that you see them.

Okay, so you can’t use that. What can you use? Well, what’s just as horrifying as a school shooter? Being a mother who learns that there’s a school shooting in progress and not knowing if her son is dead or not. That’s real horror. So Sparling built an entire screenplay around that. It’s so simple yet so brilliant that it makes you feel like every great idea does: Why didn’t I think of that myself?

Watching Amy desperately call person after person seeing if there’s anything she can do to help her child is way more riveting than anything you could’ve shown us inside the school.

Plus, Sparling adds this fun secondary plot element. It isn’t just, is my son okay? But is my son the person who’s killing everyone? In a way, that’s even worse than your son dying. So we go through a good 30 pages wondering if Noah is the shooter or not. But even after that question is answered, Sparling uses his concept to his advantage. We’re still nowhere near the school. We still don’t have all the answers. So we still have a series of phone calls to make where Amy is trying to figure out what’s going on.

The script is also a reminder that immediacy is a spec screenwriter’s best friend. Concepts with immediacy work well with specs because spec scripts are the ones readers give up on the quickest. Spec script are usually from writers trying to break in so they’re often not as good. Even if a reader likes a spec, there’s a good chance they can’t do anything with it since it’s harder to get original material made. So when you have a concept that’s immediate, the reader has no choice but to keep reading. That’s on full display with Lakewood.

Another nut that Sparling has cracked is the old screenwriting trick of making every beat of your hero’s journey difficult. A common beginner mistake is to roll out the red carpet for the protagonist. Give them all the help they need every step of the way because you want them to win at the end. Unfortunately, that’s not how good stories work. You need to make things hard for your hero. And Lakewood is a great example of the benefits of doing so.

How do you get information about someone inside a school during a shooting when nobody has any information? How do you get to the school when you’re in the middle of nowhere and everyone you know is too busy seeing if their own kids are okay? How do you get in contact with your son when he won’t answer? Sparling doesn’t give Amy a single break during this movie. Even ordering an Uber is a nightmare. Who hasn’t experienced the fury of seeing your Uber three minutes away… then check a minute later and now it’s eight minutes away? Well imagine that happening when your son’s life is on the line.

It was fun seeing Sparling go back to his roots here. This is, essentially, Buried. A guy in a coffin with a cell phone. It’s just that, this time, the coffin is the “middle of nowhere.” It’s also a GREAT way to get a movie made – a big idea (school shooting) and you could literally shoot it in 12 days. It’s just Naomie Watts out on a road. It’s crazy how cheap this probably was yet it feels HUGE. That’s the dream concept.

Don’t have anything bad to say about this one. Definitely a script all amateur screenwriters should study.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Throw out breadcrumbs instead of the whole loaf. The writer could’ve easily said, “Your son is the shooter” up front. But that’s boring. That’s the whole loaf. Writing is about leaving breadcrumbs. We learn that Noah didn’t go to school today (breadcrumb). Then we learn that’s not true. Someone saw him show up (breadcrumb). Then we learn that the police are towing his car (breadcrumb). Then we learn tomorrow is the anniversary of Noah’s father’s death (breadcrumb). Another great thing about breadcrumbs is you can lead the reader wherever you want to lead them. In other words, you can make them believe Noah is the shooter and then flip it on them. Turns out it’s someone else. Of course, none of this is possible if you throw the loaf at them right away.