Search Results for: The Days Before

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In a place distant from our normal reality, a reclusive man charged with interviewing prospective candidates for the privilege of being born must choose between an applicant he likes and one he considers tough enough to survive in the real world.

About: Edson Oda is a 2017 Sundance Screenwriters Lab Fellow from São Paulo, Brazil. Like the great John Hughes, he started his career in advertising. Not only did he write Nine Days but is slated to direct it for Mandalay Pictures as well. The script finished with 7 votes on last year’s Hit List.

Writer: Edson Oda

Details: 113 pages

Ahhhhhhhhhhh!!!

We were so close!

So close to three impressives in a row. Nine Days had me all the way up to the last 20 pages. But it didn’t stick the landing. And I’m really torn up about it because just like yesterday’s masterful script, Nine Days is a high concept premise that doesn’t feel like anything else out there. I don’t know where all these cool ideas are coming from all of a sudden but I’m not complaining.

Will is a 40-something lifeless individual who lives way off in the middle of the desert. We realize quickly that Will’s existence situation is different. He spends all day, every day, watching a series of TVs in his living room. These TVs aren’t playing the latest episodes of The Mandalorian. They’re playing lives. Real lives, down on earth, in real time. We realize that Will is somehow connected to these people, although we don’t yet know how.

Will’s favorite life to watch is Amanda’s, a 28 year old master violinist. Amanda has maximized every opportunity in life. And tomorrow, she’ll be rewarded with the biggest concert of her career. Will preps for the big day like he’s about to watch the Super Bowl. He sees Amanda practicing in her room, sees her getting her things together, hopping in her car, driving downtown… and promptly slamming her car into the concrete wall of an overpass.

Will is devastated. What happened?? He doesn’t have time to mourn the loss, though. The next day, “candidates” start showing up at his house. These candidates are people who Will will interview over a nine day period and the “winner” gets to be born. There’s the goofball, Alexander. The romantic, Maria. The introvert, Mike. The a-hole, Kane. And then there’s Emma, a strange woman who doesn’t have any interest in following Will’s rules.

The competition revolves mostly around the candidates watching the same lives Will watches every day. Will will then ask them questions about what they watched. For example, someone will watch the life of Rick, a 9 year old boy who gets bullied every day and Will will ask, “What would you do if you were in Rick’s position?”

After each day of interviews, Will speaks to his neighbor, Kyo, who, unlike Will, is a never-lived. His only job is to make sure Will does his job confidently. Will also rewatches tapes of Amanda’s life, trying to figure out what led her to suicide. He’s convinced that if he watches every moment, he’ll identify what led her to her decision. The last remaining contestants are Kane and Emma. While Kane is mentally the strongest of the bunch, there’s something special about Emma Will can’t quite put his finger on. Who will win a chance at life? You’ll have to read the script to find out.

I love ideas that help you see common things in new ways. If one character says to another character, “You’ve done nothing with your life since you graduated high school,” that line disappears the second it reaches a reader’s head. But if you show us a woman working in a factory, robotically packaging one product after another every single day and a man watching her, writing down, “7789 days since selection. No significant/relevant new event,” – that’s the kind of perspective that makes you think about life. When was the last significant event in my life? What does my life look like from someone else’s perspective? That’s what this concept brought to the table.

Oda also sets up a nice structure for his story. We know there’s nine days til the decision. It’s right there in the title. We get a good feel for how the contestants are being interviewed – what information we’re trying to get out of them in order to make the decision. But Oda doesn’t stop there. Understanding that sitting in a house for 2 hours is going to get repetitive, Oda adds two strong subplots to break things up. The first is his nosy neighbor, Kyo, who Will is annoyed by but who keeps coming around anyway. And the second is the mystery of what happened to Amanda.

It’s important when you’re writing a screenplay that has a really clean structure like this one, to BREAK THINGS UP with subplots. You don’t want the story to get into too much of a rhythm because what happens is the audience starts being able to predict things. If the pattern is never disrupted then we’re eventually going to be ahead of the writer. Subplots can be used as pattern breakers. You can also use plot twists or character twists. But subplots are nice because you can bring them in and out of the story throughout the script.

I knew the writing was strong in Nine Days early on. There are rules to learn about this world. These people coming to Will aren’t exactly alive. It isn’t clear why they’re the ages they are. We don’t know who Will is or what his exact job is. So Oda writes this montage sequence on the first day of interviews where the contestants ask him these very questions. “And if I’m selected. Am I still gonna look like this?” “And what’s the difference between being here and being alive, besides the time duration?” The best exposition is the exposition the reader isn’t aware of. And because these characters genuinely wanted to know the answers to these questions, you don’t think for a second they’re exposition.

Oda was also good at setting up these little mysteries. For example, after a day at Will’s, we’d see Kyo walking to some unknown house we hadn’t seen before. He walked up to the door, which opened, but Oda wouldn’t show us who was inside. Only Kyo greeting them and walking in. That’s one more little mystery that I have to keep reading to discover the answer to.

But the script wasn’t perfect. The big problem was Emma. Emma is the most important character in the script. And yet she’s given the least amount of screen time of all the candidates. Which didn’t’ help since she was a poorly constructed character as is. Her defining trait was smiling like she knew something you didn’t. I’m not sure what I was supposed to do with that info.

What often happens when you don’t understand the character you’ve created is you build a mystery into them and convince yourself that it’s okay if they’re mysterious to you, the writer, as well. Sorry but that never works. The writer is God. The writer has to know everything. And the reason this ending is a mess is because Oda never figured this character out.

(MAJOR SPOILER) Will ends up picking Kane over Emma. Then learns Emma left him a bunch of notes of things she noticed in his house (????). So he ran after her in the desert and performed some sort of Shakespeare sonnet for her (it was unclear what he was reciting but it sounded like Shakespeare). It was supposed to show us Will finally being vulnerable, something he’d long ago stopped doing. But his lack of vulnerability wasn’t set up well. The Shakespeare sonnet wasn’t set up well. And since I still didn’t understand Emma, him performing this for her didn’t move me at all. So the ending was a huge bummer.

BUT this concept has tons of potential. And the script is 80% there. I think Oda can get it there if he completely reworks his third act. It’s not going to be easy cause I don’t think this works until you figure out who Emma is. And figuring out characters is always some of the hardest work you do as a screenwriter. But if he can conquer that, this movie could be great.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A trap many screenwriters fall into is overthinking their bigger characters and, in the process, creating someone messy and unfocused. That’s how I would define Emma. And yet, the same screenwriter is easily able to figure out their secondary characters, like Kane. Kane is a guy who has tons of confidence and who we know will be able to handle life on earth, but will his selfishness do him in? That’s the question we’re trying to answer in Kane’s journey. So my advice to screenwriters is to not overthink your bigger characters. Yes they will have layers and yes they will have nuance. But first, identify exactly who they are and what holds them back. I promise you that the simpler their core essence is, the easier they’ll be to write.

So far in our Dialogue Series, we’ve talked about how to set up a scene for good dialogue. We’ve talked about the importance of adding personality to your characters, as that’s a driving force behind good dialogue. Today I want to talk about the kind of dialogue that makes me want to kill myself. Because I read it all the time. And if I can just steer screenwriters away from these two things, I can ensure that all the screenplays I read from now on will have 50% better dialogue. So what are these script-killers?

ON-THE-NOSE DIALOGUE

and

GENERAL DIALOGUE

On-the-nose dialogue is dialogue where the characters are speaking only to service the plot and the scene. It’s as if they have a direct line into the writer’s head and are making sure that they’re saying exactly what the writer needs them to say for the reader to understand what they’re thinking and what’s going on. On-the-nose dialogue is obvious and straightforward. “I am so tired this morning.” “You should sleep in.” “But I have the big meeting today.” “Oh yeah. I’ll cook you breakfast.”

On-the-nose characters speak like cave men. Whatever they’re thinking, they share it. This gives the entire conversation a false reality. The audience isn’t even sure why they’re so bored. Characters are speaking on the screen. Usually they like this. But nothing the characters are saying is interesting. And that’s because there’s no human element to the conversation.

What’s the human element? Well, for starters, humans rarely say what they’re thinking. If Jane shows up at work with a disastrous new haircut and asks her friend, Sally, what she thinks, is Sally going to say what she thinks? Probably not. Conversation is a dance where you’re balancing what you’re thinking against what you’re saying. And I think that’s what a lot of newbies get wrong. They have the character say what they think as opposed to considering how that character might present that thought once it goes through their filter.

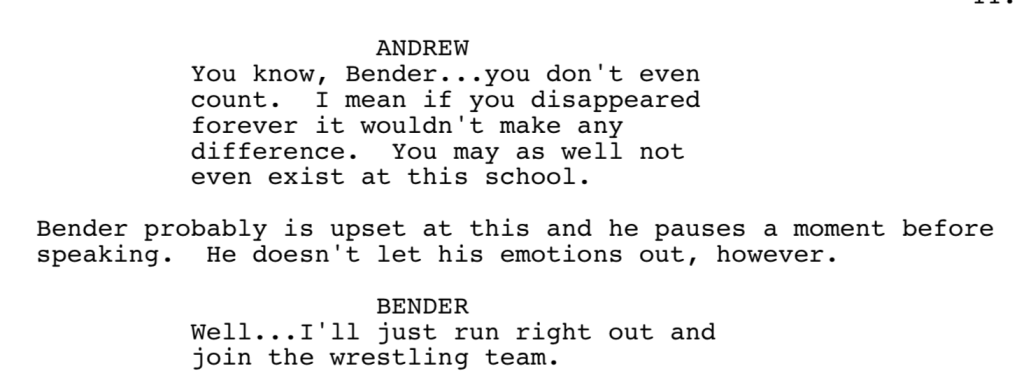

Here, in The Breakfast Club, Andrew (the Jock) is mad at Bender (the Burnout) and lets him know it….

You can see that John Hughes even wrote it into the script. Bender wants to say something nasty. He’s angry. But instead of being a robot who conveys exactly what he thinks, he pretends that he’s unaffected and comes back with a jab. This is the human element. We think about what we’re going to say so that when we do say something, it frames us in the light that we want to be perceived in.

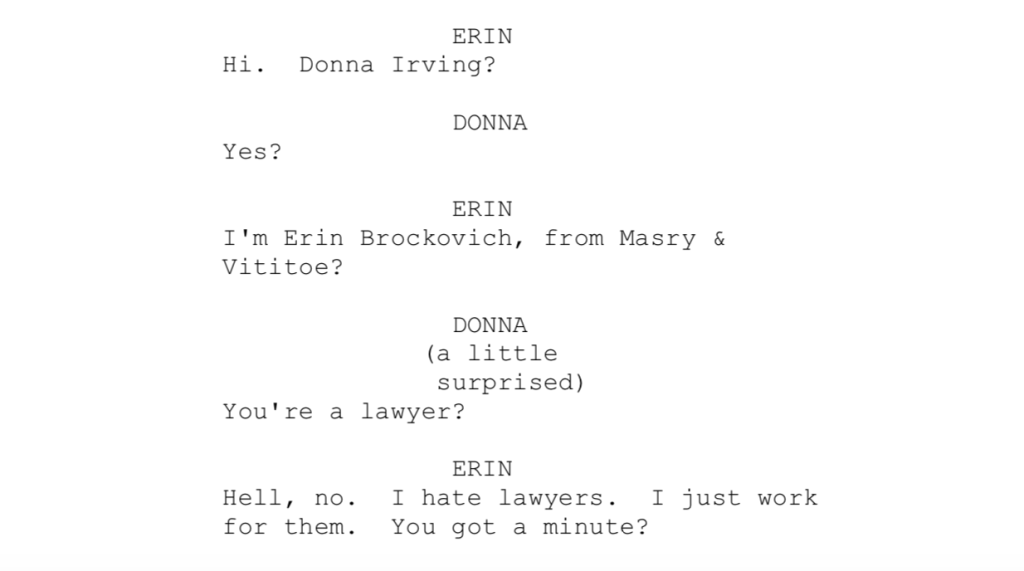

I can tell a writer is thinking “off-the-nose” (which is what you want!) when obvious questions are asked and non-obvious responses are given. Here’s a quick exchange in Erin Brokovich, where Erin is going to a woman’s house to get some information on the water scandal that’s hit the county.

I’ve read a hundred scripts where a character asks a question just like this. “Are you a lawyer?” And the on-the-nose response from the lawyer is, “Yes, do you have a moment?”

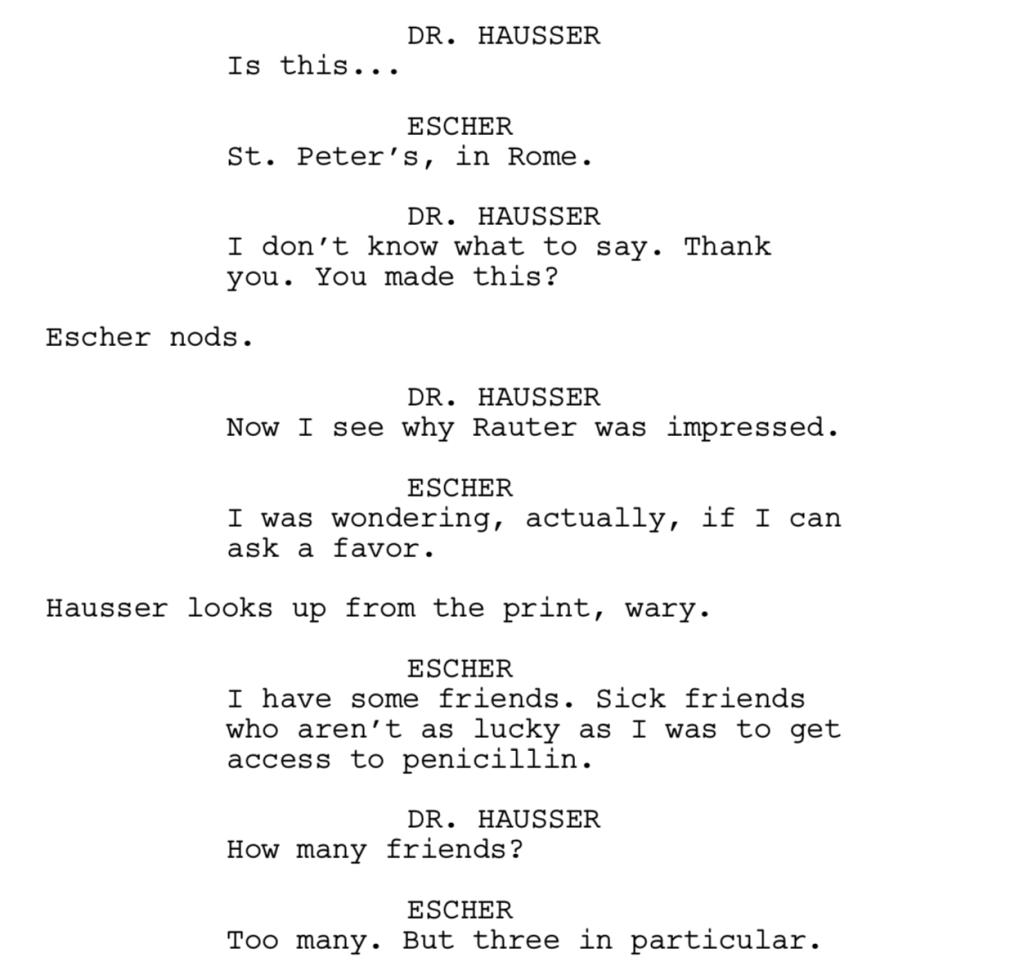

It should be noted that on-the-nose dialogue becomes harder to avoid the more heavily plotted your script is. If you have a ton of plot, then your characters will become mouthpieces for the plot instead of real people having real discussions. This was a problem with yesterday’s script, Escher, which had a lot of plot going on, so all the characters needed to say exactly what needed to be said.

I bring this up because on-the-nose dialogue is often a result of circumstance. You’ve created stories or situations whereby the characters have to say exactly what they’re thinking. This is why you want to leave enough freedom in your story to let your characters talk without the constraints of needing to convey a plot point every three lines.

To avoid on-the-nose dialogue, avoid logic. Logic is your enemy in dialogue. Try to be playful. You want to have fun with your characters as opposed to just asking and answering questions. And try to incorporate scenes where one character isn’t being completely honest with the other. Or is holding back on some truth or their feelings. Once you have characters who aren’t being 100% honest, it’s hard to write on-the-nose dialogue.

Let’s move on to GENERAL DIALOGUE. General dialogue is dialogue that is the bare bones generic version of what a character can say. For example, if a character is at Thanksgiving dinner and wants more mashed potatoes, he might say, “Can someone please pass me the mashed potatoes?” This is a perfectly acceptable thing to say in real life. But in a movie, the line is so generic, it’s invisible.

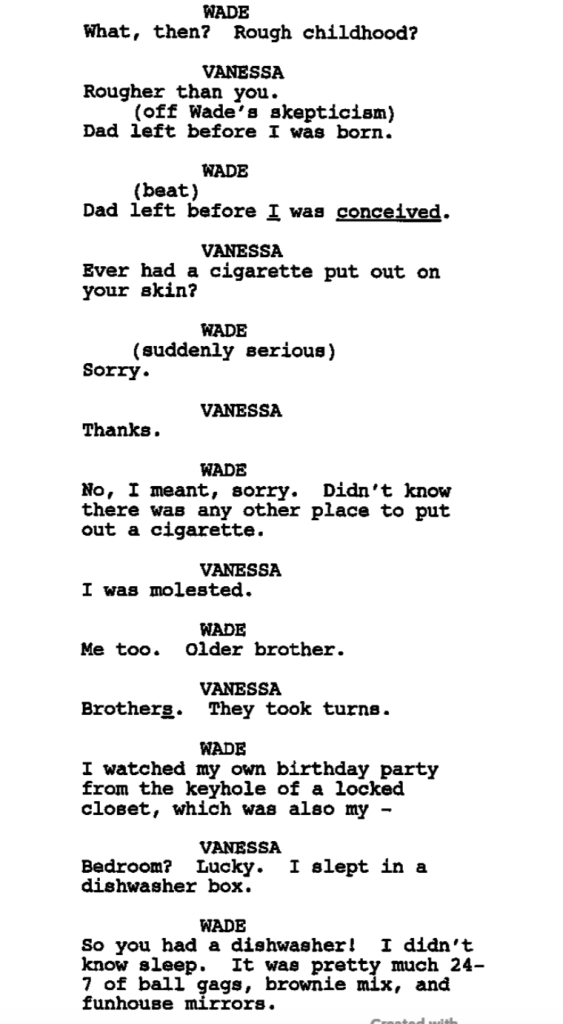

The way you battle general dialogue is through specificity and playfullness. You add words and phrases and angles that add flavor to the line. Your hungry character might nudge his sister and whisper, “Hey, snag me the mashed potatoes before Uncle Rick engulfs them.” It’s not a crazy better line. But it’s more specific. The word “snag” is a little different. “Uncle Rick” makes the line unique to the story. “Engulfs” is a slightly dressed up way of saying “eats.” How specific you get will depend on the character, the story, the situation, and the genre. This line wouldn’t work in, say, Schindler’s List. Let’s take a look at an exchange from Deadpool.

Notice how specific this dialogue gets, particularly towards the end with those last few lines. The two get into some pretty graphic experiences. Of course they’re not real, which makes the dialogue “off-the-nose,” and a solid example of everything I’m trying to teach in this post.

For the next exchange, we’re going to Fast and Furious 4. In the scene, Han is paying Dom for the job they just did…

Look at the specificity in the words and phases. “Skippin’ out?” “Simple economics. Profit’s drying up here.” “Getting a little tired of rice and beans.” “I hear they’re doing some crazy shit in Tokyo.” “This nickel and dime stuff.”

All that’s really happening here is that the writer is willing to play with words. That’s the attitude you want to have whenever you’re writing dialogue. Obviously, the extent with which you’ll play will depend on the scenario and characters. But even if it’s two stiff accountants sharing plot information, you should still find ways to play with the words so it doesn’t come out like two robots talking.

That’s the worst thing that can happen to dialogue. On-the-nose generic “just the facts ma’am” conversation. Throw in some off the nose specific dialogue – be willing to play with words and phrasing – and your dialogue’s going to get a lot better.

Yo, do you have a logline that isn’t working? Are those queries going out unanswered? Try out my logline service. It’s 25 bucks for a 1-10 rating, 150 word analysis, and a logline rewrite. I also have a deluxe service for 40 dollars that allows for unlimited e-mails back and forth where we tweak the logline until you’re satisfied. I consult on everything screenwriting related (first page, first ten pages, first act, outlines, and of course, full scripts). So if you’re interested in getting some quality feedback, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll send you a quote!

Over the next five Thursdays, I’m going to be talking dialogue with the Scriptshadow Community. We’re going to be exploring the five main factors that go into writing strong dialogue, and today we’re starting with scene prep. The objective of this post is to show you how to prep a scene in order to get the best dialogue out of it.

Before we get into what you should do, it’s important to understand what not to do. As a screenwriter, we’re taught to look at scenes as situations that move our story forward. For example, as you plan your scene, you may think, “I have to have Chloe tell Jack about the time machine glove here so that when they meet up with Dr. Frank after the graduation scene, they can go back in time that night.” In other words, you see the scene as a means to communicate information as opposed to an entertaining experience in itself.

That’s the switch I want you to make in your mind. Of course you want your scenes to push the story forward. But what’s more important is that each individual scene be entertaining. It may be scary to hear but three boring scenes in a row and the reader is out.

The most basic step in dialogue prep is making sure that one character in a scene WANTS SOMETHING. The reason for this is that it gives your character purpose. And when a character is purposeful, his words have meaning behind them. Words without purpose, without meaning, are lifeless. To see this in action, write up some dialogue where two characters don’t want anything from each other. See what comes out. I’m guessing a bunch of boring nonsense.

Here’s where things get fun. Once you have a character who wants something, you can set it up so that the other character in the scene doesn’t want to give it to them. Go write a scene right now where Nick wants to break up with Tara but Tara doesn’t let him. I guarantee that scene is going to have better dialogue than if Tara agrees with Nick that they should break up. By following this simple formula, you’ve added CONFLICT to your dialogue. And conflict is where most great dialogue lies.

While this setup works great, not all conversation is this cut and dry. To be honest, if you only wrote scenes where one character wanted something and another character didn’t want to give it to them, the script would get repetitive fast. Conversation is more varied and nuanced than that. However, I want you to master this basic setup, because we’re going to use it as a jumping off point for all the other dialogue situations.

A close cousin to the “want – don’t want” setup is the “talk – no talk” setup. This is where one character wants to talk about something and the other character doesn’t. How many times have you been in a relationship or a marriage where you came home and your spouse hits you with the last thing you want to talk about in that moment? That’s an ideal dialogue situation right there. I actually think one of the most fun types of scenes to write is a “talk – no talk” where the secondary character literally says nothing the whole scene. Character A is the only person who talks in the scene. These scenes are always good.

Because conversation is so complex, these two setups are not going to be enough to complete the 40 odd dialogue scenes you’ll write in a screenplay. There will be a number of scenarios where neither character wants something and where both characters want to talk to each other. How do we still make the dialogue pop in those situations? It’s called the “Tension Question.” When dialogue lacks bite, simply ask the question, “Where is the tension coming from?” If you don’t have any, the dialogue will lack spark.

An example of tension is sexual tension. I was watching The Office the other day and Michael Scott was talking to his female boss and neither of them wanted anything from each other. But the scene worked because there was sexual tension bubbling up underneath their conversation. You could even make the same scene work if the sexual tension was one-sided. AS LONG AS THERE’S TENSION. That’s how important the Tension Question is.

Yet another great dialogue setup is to introduce an external problem into the scene. A problem forces your characters to work the problem out. But wait. Doesn’t that violate our first dialogue commandment, which states that our characters can’t want the same thing in a scene? Actually, the tension comes from a slight adjustment. They may want the same thing, BUT THEY’LL HAVE DIFFERENT OPINIONS ON HOW TO GET IT. Have you ever tried to lift something really heavy with people you barely know? Within seconds, you’re getting wildly differing opinions on how to execute the task at hand: “No no no, you got to be in front.” “Wait, you should put your hands here, not there.” “You’re the tallest so you should be in back.” If characters want the same thing, they should have differing opinions on how to get it. That’s going to inject the necessary tension.

These final three structural tips aren’t required for great dialogue, but if your dialogue is lacking punch for some reason and you can’t figure out why, try throwing one of these in there. STAKES. The more that’s on the line, the more the words will matter. Think about a scenario where absolutely NOTHING is on the line. Say you’re meeting up with a friend for coffee. Neither of you want anything from each other. This is a zero stakes conversation which means it will be 100% boring. What if, however, using the same setup, Character A needed to borrow a large chunk of money from Character B to pay off his bookie, or else that bookie is going to break his jaw tonight? Granted, that’s an extreme scenario. But do you see how stakes increase the conversation’s worth? It doesn’t need to be this drastic every time. Just ask yourself, “What’s on the line in this scene?” If nothing is on the line, putting ANYTHING in there will improve the dialogue.

The second tip is URGENCY. A conversation where characters have all the time in the world to chat away is usually a boring conversation. For this reason, you want to put a time constraint on your conversation. I was watching a TV show not long ago and Character A needed to talk to Character B about something important. The writer didn’t have the two meet later for a beer to discuss the issue – a place where they would’ve had an endless amount of time. Instead, Character A came to Character B’s work. Character A spotted him in a meeting and waved him out. Annoyed, Character B came out and said, “What are you doing, I’m in the middle of an important meeting,” and Character A laid the issue on him. Of course, he had to hurry because Character B’s coworkers were waiting for him to come back into the meeting. Lack of time equals pressure. Pressure equals tension. Tension is conflict. Conflict is entertainment.

Finally, we have circumstance. When and where a conversation is had will have a major influence on what’s being said. The same conversation plays differently in a bedroom than it does in a plane than it does at a wedding than it does in the supermarket line than it does at a funeral. That’s because different circumstances create different levels of tension (not to mention different types of tension). A good rule of thumb is that if a conversation is going to be entertaining on its own, you don’t need to think too hard about circumstance. But if your conversation is weak, try altering the circumstance to a time and place that’s going to add more tension.

That’s all for today. Come back next week where we’ll talk about character. In the meantime, you better be writing a bunch of practice dialogue scenes with these tips in mind!

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Biopic

Premise: Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse battle it out to light the Chicago World’s Fair. The winner will end up lighting America.

About: Graham Moore burst onto the scene when he wrote The Imitation Game, a script that snagged the top spot on the Black List and then went on to surprising box office success. Moore would eventually win the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. The scribe, an admitted history junkie, did double duty this time around. He wrote a book about Edison and Westinghouse, then adapted it himself. The film will reteam Moore with Benedict Cumberbatch, who will play the prickly Thomas Edison, and director Morten Tyldum. The film will also star Eddie Redmayne as the main character in lawyer, Paul Cravath. (edit, oops! I got these two projects mixed up. Cumberbatch is appearing in The Current War. My fault!)

Writer: Graham Moore

Details: 134 pages

While everybody’s worked up about the upcoming Oscars, I’ve already moved on to next year’s Oscars! And today, we have what will surely be a major contender in the top categories.

Moore finds himself in a very enviable position. He’s a screenwriter who loves biopics living in the golden age of biopics. Outside of a couple of names (Aaron Sorkin comes to mind), there isn’t anyone better than him at it. And he’s proven that again, today.

26 year old Paul Cravath was only in law school two short years ago. Now he’s been tasked with telling one of his firm’s biggest clients, George Westinghouse, to give up his bid for lighting Chicago’s World Fair.

It’s 1888, a time when electricity is just starting to make its way into cities. Everyone knows that whoever can win this war will be rich beyond comprehension. The person leading the pack is Thomas Edison, who’s created a functional, if sloppy, light bulb.

George Westinghouse, on the other hand, has created a light bulb with the kind of warm dreamlike glow that leaves you feeling all fuzzy inside. The problem is that Edison came up with his bulb first. And he’s suing Westinghouse on a number of fronts to make sure he can’t light the fair.

Now that doesn’t sound fair, does it?

Westinghouse, against the advice of the firm, employs Paul Cravath to fight Edison tooth and nail. There has to be a flaw in his patent that will allow Westinghouse to win this battle. The problem is that Paul doesn’t have enough manpower to fight someone as big as Edison. There aren’t enough hours in the day.

So Paul invents the first ever hierarchal legal research system, employing associate attorneys who can do the medial work for him so he can focus on the big picture. Ironically, this system is as inventive as the light bulb, as it would become the operating foundation for every working law firm today.

But will that be enough to take out Edison? Only one way to find out.

I always find it interesting where a writer places his point of view. I mean, you have Thomas Edison. You have George Westinghouse. They are the “big picture” characters here. Yet Moore chooses to tell his story from a lawyer’s point of view. Was that a smart move?

Well, the core component of all drama is conflict. Where the conflict lies is where the entertainment is going to be. So Moore asked, where do these two titans meet? They meet at the point of this patent. And wherever there’s a patent battle, there’s a lawyer.

I probably wouldn’t have done this myself because when I think “lawyer,” I think “boring.” Especially a patent lawyer. But Moore treats his lawyer much like Tom Cruise’s part in A Few Good Men (not surprisingly, an Aaron Sorkin creation), where he plans to get Edison in court and force him to admit he cheated on the patent.

And that’s all well and good. But what I like about Moore is he has the ability to surprise you in a genre that’s plagued by its plainness.

Halfway into the story (spoilers), Westinghouse loses the patent battle to Edison. That’s right, HE LOSES. Not only is this a great plot beat (we’ve lost the battle with half the script remaining. Everyone’s asking, where do we go now??), but it allows Moore to introduce a third character.

Nikolas Tesla.

And I will tell you right now. Whoever plays this part is going to be a breakout star (unless he’s already a star). Moore goes so kooky with Tesla that you can’t look away from him. There’s a great little screenwriting tip here. Give a character a DEFINING ACTION, and if that action is strong enough, we’ll know exactly who that character is for the rest of the script. Moore focuses on Tesla’s “weird wave.” He keeps making this weird uncomfortable wave around people, and it perfectly embodied his oddness.

Tesla’s created a different kind of electricity that would not be bound by Edison’s patent. But Tesla’s a wild card. He’s got zero infrastructure. So Paul tells Westinghouse, who does have infrastructure, to team up with Tesla on his bid. The two become an unlikely pair with a common goal. Take out Edison.

Whenever you write biopics – hell, whenever you write a script – you need CHARACTERS. This is something it took me years to figure out. I was always a plot junkie. I thought fun stories, cool twists and great set pieces were the key to writing a great script.

But, in reality, it’s the characters. Because characters are interesting on their own. You can place a good character in a mediocre scene and we’ll still be drawn to him. Thomas Edison is a great character. He’s a fucking asshole. He’s full of himself. The man SUED HIS OWN SON! Whenever you put that guy in a scene, we pay attention.

Nikolas Tesla is a great character. He’s quirky, he’s weird, his mangled English leaves you scratching your head every time he speaks. The surprise element of Tesla makes him a fascinating character to watch as well. We never know what he’s going to do next.

Now here’s where the character argument gets interesting. Somebody in your script has to be the straight man. They’re the person who grounds the script. In most cases, this will be the hero. As a result, your hero ends up being the most challenging character to write. How do you make this person as interesting as an asshole, or a weirdo?

This is where a screenwriter earns his mettle. Because it isn’t easy. However, there are little things you can do to make us care. For starters, you can make your hero extremely determined. Audiences love determined people. You can make him an underdog. Audiences love rooting for the underdog.

Admittedly, these are “straight man interesting traits,” and therefore will never be as fun to watch as an outlandish part. But played right, we’ll be invested in the character’s journey. You can then use the orbiting characters to add a dose of spice to the story.

Of course, you don’t HAVE to make the main character the straight man. Alan Turing in The Imitation Game was offbeat. The same thing can be said for Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street and John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. So it’s all a matter of whose story you’re telling and who’s point of view you want to tell it from.

As for the rest of the script, Moore includes some classic screenplay elements. We have a ticking time bomb – everything must be done before the World’s Fair. We have the “impossible task” (we’re told at the beginning that Edison’s lightbulb patent is one of the most airtight patents in history). We have that conflict I referred to. You can feel the weight of these two titans crashing down on the plot at all times.

The only problem I had with the script was the beginning. I didn’t understand why the heads of the firm were trying to get Westinghouse to pull out of a legal battle with Edison. Since when has a law firm ever turned away the money of its rich clients? That felt a bit forced to me.

But outside of that, this script was as bright as its subject matter. Moore has proven, once again, that he’s a hell of a screenwriter.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure to remind your audience that your hero’s task is impossible. Hearing someone say, “Edison’s patent is the most airtight patent in history,” prefaces just how difficult the journey will be. Had this line not been written in, I wouldn’t have realized just how much of an uphill battle this was.

I will be announcing the TOP 25 scripts from my contest this Wednesday!

And as we get closer to the big day where worlds will be moved, lives will be changed, I can offer some thoughts on the process, a process that has given me even more insight into the system than ever before. The biggest takeaway I’ve gotten so far? That it takes a long time to get this craft right. Almost inevitably (with a few exceptions), when I like a script and go back to read the writer’s pitch e-mail, I see it mentioned that the writer has been at this for 7 years or 8 years or 9 years. Screenwriting, unlike any other form of writing, has a mathematical component. You’re supposed to hit beats by certain pages, divide things up into acts, keep the script under a certain page count. To get used to that restriction – to be able to write freely within those guideline – takes time and practice. And you can feel it on the page. You can feel that ease, that lack of fear. With new writers, they’re mostly just writing whatever comes to mind at the time. Filling up pages, hoping to have enough before they write “The End.” The stories feel unformed, random, like we’re on a bus ride to nowhere. This doesn’t mean you’re screwed if you’re new to this. But if you’re going to compete with these people, you’re going to need to work a hell of a lot harder. READ, STUDY, WRITE. That needs to be your life. READ, STUDY, WRITE. If you’re not doing one of those three things, you’re not catching up to the people who have been doing this so much longer than you have.

TWO DAYS LEFT!