Genre: Comedy/Drama

Premise: Two scientists must go on a press tour to answer questions about an impending asteroid collision that will destroy all life on earth.

About: Big one today, guys. Some might even say it’s an extinction-level script. This is the big Adam McKay Netflix project that’s to star Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Jonah Hill, and Timothy Chalamet. Of his return to comedy, McKay said, “I don’t think it’s a ‘Step Brothers’-type of comedy. I would compare it more to somewhere between the Mike Judge stuff and ‘Wag the Dog.’ A hard funny satire is what we’re going for.”

Writer: Adam McKay

Details: 125 pages (Jan 2020 draft)

There aren’t too many scripts I get excited for these days. I’ve read so many screenplays and so many writers that I pretty much know what to expect when I open a script. That all changes today. Today’s screenplay combines a guy who I believe is one of the most talented in Hollywood, Adam McKay, with a unique idea. It also has an interesting cast. I mean, who would’ve thought that Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence would ever work together? I can’t think of two people more polar opposite. All of this implies that we’re getting something special. Famous last words, right? Let’s jump into it.

Scientist Kate Dibiasky works for tenured Michigan State professor Randall Mindy. During a party, Kate does a little work and, while tracking a comet, watches it collide with an asteroid, which then sends the asteroid on a collision course with earth.

Kate tells Randall, who confirms with everyone in the department that, yes, this thing is going to hit and destroy earth in six months. So they call the White House and get a meeting with the president, but to their dismay, the president says they want to sit on this information for three weeks, as they don’t want to throw any wild variables into the upcoming election.

Since every second passed is one more second the world isn’t stopping this asteroid, Kate and Randall go on a publicity tour to warn the world, in the hopes that it motivates our government to stop this thing. Except the exact opposite happens. Nobody takes them seriously. Even on the big shows, their interviews don’t trend. Everyone thinks their story is cute but, you know, not likely to be true.

As Kate gets angrier and angrier, Randall starts to cozy up with the White House, despite the fact that they’re not doing anything. Which makes Kate even angrier! Eventually, even the president can’t deny that this asteroid is coming for them. And so they FINALLY come up with a plan to send nukes at the thing and knock it off course.

But during the launch, just as the nuke delivery guy has made it to space, he TURNS AROUND. What’s happening, Kate demands. Well, it turns out the Elon Musk-like Peter Isherwell has discovered over 4 trillion dollars worth of gold and diamonds on the asteroid. He’s made a deal with the White House to use a series of drone-nukes that will latch onto the asteroid at strategic spots, blow it up into small pieces, which they can then mine from the ocean.

The problem with this plan is that the asteroid is now so close that if something goes wrong, they won’t have another shot to destroy the thing. Will they be able to pull this mission off? Or is everyone going to die because no one will acknowledge that this great big asteroid is really going to hit us?

One of the first questions that popped into my head while reading this was, “Why did Leonardo DiCaprio agree to make this movie?” The character of Randall isn’t like anything he usually does. I don’t remember the last time DiCaprio did comedy. I guess he’s sort of comedic in Tarantino’s movies. But I don’t think he’s ever done satire, has he?

Anyway, it all became clear when I realized this movie was an allegory for global warming. It’s about the fact that there’s this giant asteroid coming at us but nobody wants to “look up.” They all stare at the ground and ignore it in favor of the latest tick tock drama or what sexual misgiving the newest supreme court nominee engaged in 30 years ago. Global warming is DiCaprio’s passion (even if he likes to fly private jets everywhere). So if you share DiCaprio’s passion for this subject matter, you too, will probably enjoy this.

As a story, though, I had trouble getting into it. Satire has never been my thing. So that’s part of it. But the bigger part is that I didn’t care about Kate or Randall. And isn’t that what it always comes back to? It doesn’t matter if you have a great plot. It doesn’t matter if you’re passionate about the subject matter. If we’re uninterested (or even casually interested) in your characters, it’s not going to work.

Kate is one-note. All she does the whole time is be pissed off. That’s it. She tells people about the asteroid and when they don’t take it seriously she throws up her hands and says, “I’m done.” When you repeat the same beat over and over again for a character, that character becomes boring quickly.

Randall is a little more complex. He’s got this cheating scandal going on and he eventually turns to the dark side by cozying up with the president. But I never got a handle on him at all. At least with Kate, I could designate her. She was “the angry character.” You could give me all the time in the world and I still wouldn’t be able to tell you what kind of person Randall was.

This is why I remind writers, early on in their script, to figure out your character’s defining trait. Joker wants to fit in with the world. Jordan Belforte is addicted to excess. In Run, the mother loves her daughter too much. I don’t have any idea what Randall wants. And that hurts the story because if you have one character who’s too thin and another who’s undefined…. You don’t have a movie.

I’m going to make a grand assumption here and guess that McKay was so set on exploring his theme that he overlooked the people delivering it. This happens to all writers. Whenever we start a script, we have a specific reason we want to write it. Maybe it was the concept, a character, a theme, we want to tell a breakup story because we just went through a devastating breakup. Whatever it is, it’s often specific. What happens, though, is we develop a blindspot to everything else in the story. Those other variables aren’t the reason we wrote the story so we don’t care about them as much.

The script does have some funny moments. There’s a whole thread about “impact deniers.” Congress doesn’t initially approve the “Save The Planet Bill” due to partisan politics. The woman Randall has sex with gets off on being told the specific scientific ways the asteroid is going to destroy the planet. And there was the occasional funny line, such as this exchange in an early interview on a news show – Kate: “Well, it became apparent that the large asteroid’s orbit was changed by the hit, the collision… and it is now on a course to directly and catastrophically hit earth in just over five months.” Newsperson: “Now how big is this rock? Could it damage say, someone’s house?”

Also, even though I wasn’t that invested in the story, I did want to read til the end. There’s something to be said about a strong hook and wanting to see how that hook is resolved. I genuinely did not know, until the last 15 pages, if McKay would have earth get its s%$# together or kill everyone off. So at least I was uncertain where the story was going, which is more than I can say for most of the scripts I read.

But I don’t know, guys. I’m neutral on the script’s theme. The main characters were average at best. I didn’t laugh as much as I hoped to. And satire is one of my least favorite genres. When you add all those things together, you get my lukewarm response. It seems like a good movie to put on Netflix though. I’m not convinced something this off-center could have been produced for theatrical distribution. What do you think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Spec screenwriters should stay away from the satire genre. It’s one of those genres, like dark comedy, where the execution bullseye is microscopically small. This tends to be a “showoff” genre anyway. A genre for those who like to prove how smart they are. But even if you’re good at it, the chances of you sticking the landing on one of these scripts is incredibly small. Therefore, I’d steer clear.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) A homeschooled teenager begins to suspect her mother is keeping a dark secret from her.

About: This comes from the same guys who made the really cool “all-computer-screen” thriller, “Searching.” Quick fact that shows how frustrating the transition from page to screen is: Originally, this script had a big outdoor ending sequence. However, after shooting in Winnepeg for a few weeks, one of the coldest cities in the world, they were getting some complaints from their actors about the weather and therefore had to rewrite the entire ending so it was indoors! During production! So the next time you’re struggling to come up with an ending, remember that it could be a lot worse. You could be told that the ending you spent six months perfecting needs to be rewritten one week before shooting.

Writer: Aneesh Chaganty, Sev Ohanian

Details: 90 minutes

I feel bad for these guys because, after the huge success of Searching, this was supposed to get a major theatrical push, something that’s getting harder and harder to do for a movie of this size. However, the pandemic screwed all that up like it’s screwing everything up and “Run” went to streaming instead. But hey, that’s good for us, right? We don’t have to leave our couches to catch the latest buzz-worthy flick. Let’s take a look.

Diane and her 17 year old daughter, Chloe, have a peaceful life, all things considering. Chloe is a paraplegic who must get around in a wheelchair, which has forced Diane to be a full-time carer, but the two have a strong relationship as it’s clear Diane loves her daughter more than anything.

But lately, Chloe has been restless. She’s trying to get into college but every day she races to the mail, her mom beats her to it. It’s almost as if her mom is keeping mail from her. Maybe even an acceptance letter?

In addition to this, Chloe takes a LOT of medication. All supervised by her mom of course. And she’s beginning to wonder what this stuff is. Unfortunately, she’s not allowed to use the internet or even own a smart phone. Which limits her access to information.

Therefore, Chloe must get creative and look for opportunities when mom is gone. She finally uses a trip to the movies as an opportunity to say she has to go to the bathroom. She sneaks across the street to the pharmacy to ask what this pill is she’s been taking. She learns it’s a pill that causes people to lose feeling in their legs!

Now Chloe knows the truth. Her mom is a psycho. Which means she needs to escape. But that’s easier said than done. Especially because her mom is now on high alert (she discovered Chloe at the pharmacy at the last second).

Chloe will have to figure out a way to both escape their home and make her way into town, a several-mile drive with only one road to and from. Is that possible for a girl restricted by a wheelchair? And why do we get the sense that if Chloe doesn’t escape soon, her mother is going to do something a lot worse than paralyze her?

Let me start off by saying it’s scripts like this that got me into screenwriting in the first place.

You find a fun idea then build a narrative and series of scenes that best exploit that idea. That’s what “Run” is. You have this cool thriller concept where a teenage girl begins to suspect that her mother is holding her hostage. This necessitates our goal – escape. That goal is achieved by a series of scenes – our hero trying to escape. Those are the scenes that are going to make or break your script because those are the scenes that are fulfilling (or not fulfilling) the promise of your premise.

This was always my favorite part of writing. Coming up with those scenes. Debating, after you came up with one of those scenes, whether they were good enough. Whether they were working. Whether you could come up with something better.

“Run” does a pretty good job in this department. There’s a scene around the midpoint where Chloe has been locked inside her room. After her mother leaves the house, Chloe tries to escape by going out of her second-floor window, crawling along the roof, and getting back in through a window on the opposite side. In any other movie, this would be easy. But for someone without the use of her legs, it becomes a harrowing ordeal.

When she finally gets outside the house, she tries to wheel her way into town, and runs into the mailman on the country road. After he stops, she tells him everything. Only for her mom to pull up behind the mailman and attempt to convince him that her daughter is unwell and please just hand her over. I was on the edge of my seat hoping the mailman didn’t give in. Please, for the love of God, Mailman. Don’t give in!

But something I found that’s unique about this type of hostage situation – one where our captive has a lot of freedom (as opposed to when a serial killer has their captive chained up in a basement) is that it’s hard to imagine, with 24 hours in a day, 7 days in a week, that our captive couldn’t find a way out.

We set up some rules early on that Chloe doesn’t have an iPhone. She doesn’t have internet access. Which limits her ability to find out if these pills mom is giving her are poison. So there’s this scene where Chloe literally calls a random number and asks a busy man to look up something on the internet for her. And I’m thinking to myself, “I’m not sure this scene is a) believable, or b) the most logical way to answer this question.”

It was a reminder of how shaky the foundation of this setup was. Is it really that impossible to get information? The suspension of disbelief in this script was as fragile as cheap china. You got the sense that it could be shattered with even the smallest disturbance. And that definitely affected how much I believed what was going on.

For example, there’s this scene late in the movie where Chloe poisons herself to force her mom to take her to the hospital. And, presumably, as soon as she wakes up, she’s going to tell the doctors the truth about her mom. So Chaganty and Ohanian place this medical throat restriction device on Chloe so that even when she wakes up, she can’t speak yet. So Chloe mimes to the nurse she has something to say and the nurse finally gives her a crayon and a piece of paper. Chloe is finally going to be able to tell someone what her mom is doing to her!

Yet all I could think was: You’re saying that there isn’t going to be a single other second in this hospital where she could tell them the truth? Even under the most restrictive realistic scenario, you have to think that our heroine would be able to convey that her mom is dangerous.

For a movie like this to work, you want all of these illogical pockets to be eliminated. That’s why the mailman scene was the best in the movie. There weren’t any holes in it. We felt like this is really how it would’ve gone. Yes, if a mailman saw a frantic girl in a wheelchair trying to run away, he would stop to see if she was okay. Yes, if she told him her mother was imprisoning her, he would try to get her to the police. Yes, if the mom drove up at that moment, she would lie to him to get him to hand her over. Yes, if we were that mailman, we would listen to that mother, albeit skeptically. And, most important, we knew that if the mom won this argument, our heroine was screwed. That’s a strong scene right there no matter which way you slice it.

While the believability of the set pieces was hit and miss, I loved how the writers structured their script. The challenge with structuring these “captive” movies is that even the most elaborate escape is going to take, what? 25 minutes? 30 tops? So that’s your ending. Those last 25-30 pages. What do you do in the meantime? Especially because your hero will typically want to escape by the end of the first act.

What Chaganty and Ohanian do is they use the first quarter of the script as an investigation story. Chloe suspects her mom is giving her pills that are keeping her sick. So she needs to find out if that’s true. When she finds out they are, indeed, bad, we’re a little past the end of the first act.

Again, if you start the escape now (or even the planning), you’re going to need to make it last 75 pages. That’s impossible. So Chaganty and Ohanian do something clever. They have her plan and launch an escape, only for it to fail at the midpoint (the mailman scene). This places Chloe right back in the home, except under much more dire circumstances. The ruse is up. So there’s no reason for her mom to pretend anymore. Which means Chloe is in a lot more danger. Now she REALLY has to escape.

After Chloe assesses her situation, her mom returns from getting some suspicious materials and it looks like she’s going to double down on this “making Chloe sick” stuff. The two tussle and Chloe comes up with the plan to poison herself so her mom has to take her to the hospital. And now we have our final “escape” laid out for us. This is her last chance to run away from her mother forever. Structurally sound stuff!

“Run” is one of those movies that hums more than it sings. But it still comes up with a few melodies you can’t stop humming to yourself. Like but didn’t love!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great development for any script where your hero is held captive is the “FALSE ESCAPE” at the midpoint. Your hero does it! They successfully escape their captor! Only for, at the last possible second, the captor pulls some impossible move and captures them again, bringing them back to their prison. This not only helps you structurally. But it heightens the intensity of the second half because now the captor is enraged. They’re way more dangerous now than they were before, and escape truly feels impossible.

It’s an all-new all-different but-still-kinda-the-same Amateur Showdown! If you haven’t been to the site in a while, this showdown might be confusing, so let me give you the Cliff’s Notes version of what’s going on.

I hosted a screenplay contest called, The Last Great Screenplay Contest. I read the first ten pages of every entry and divided the scripts into four categories. Yes, High Maybe, Low Maybe, and No. Originally, I was only going to guarantee 10 more pages of reading to the Low Maybes. Then I came up with the idea that we would take the top 20 (actually 22) Low Maybes and pit them against each other in four Amateur Showdowns.

The winning script in each of the next four Showdowns will compete with each other in a final fifth-weekend Super Showdown, and that winner will advance to the Finals of the contest.

Confused?

Don’t worry. All you need to know is that this is like any other Amateur Showdown, except the stakes are much higher. So I need everyone here to read as much of each script as you can and vote for your favorite in the Comments Section by Sunday evening at 11:59pm Pacific Time. The script with the most votes moves on to the fifth and final Super Showdown.

I think you’re going to like this. A lot of the scripts that went into the Low Maybe pile had strong concepts, in a lot of instances stronger than the High Maybes. But for whatever reason, their first ten pages didn’t blow me away. By getting a second look from you, the readers of the site, I’m sure a script or two will emerge as a true contender.

Quick note. We’re doing a Plus-Sized Showdown next week starting on Wednesday that will have 7 scripts, since it’ll take place over the long Thanksgiving Weekend. So that Showdown should be extra fun.

Let’s get started with today’s entries. Good luck, everyone!

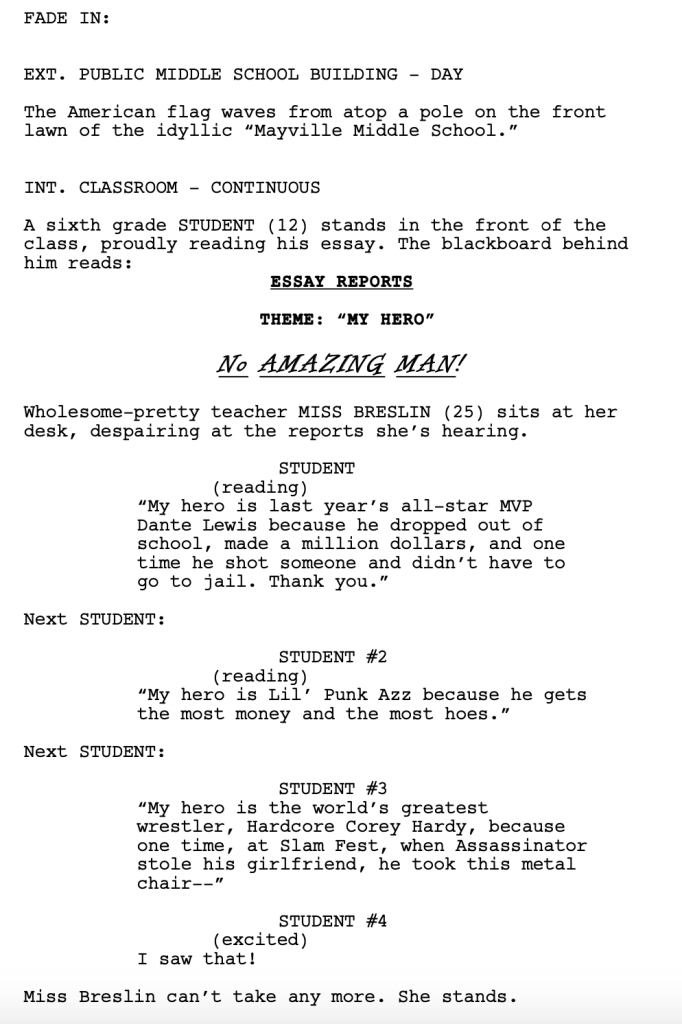

Title: Our Hero

Genre: Family Comedy

Logline: When 3 nerdy middle school kids discover the secret lair of a burned-out superhero; the world’s most powerful man agrees to be their friend in exchange for keeping his secret.

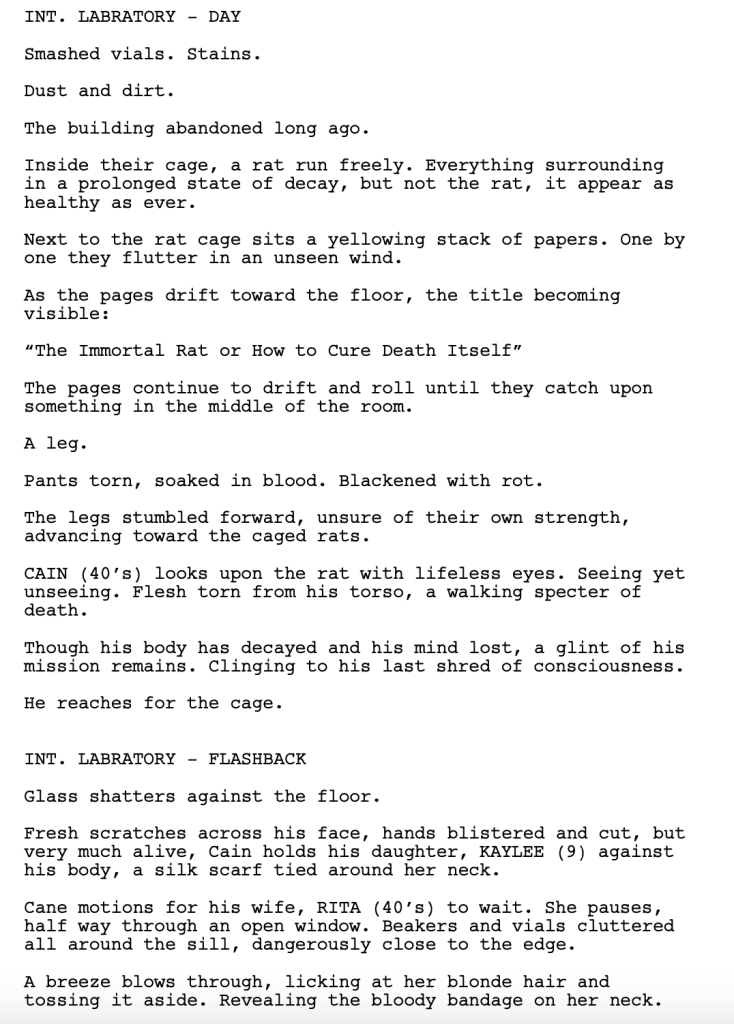

Title: Night of the Living

Genre: Horror

Logline: Years after humanity’s extinction, the idyllic life of suburban zombies is shattered when an outbreak of humans threatens their existence.

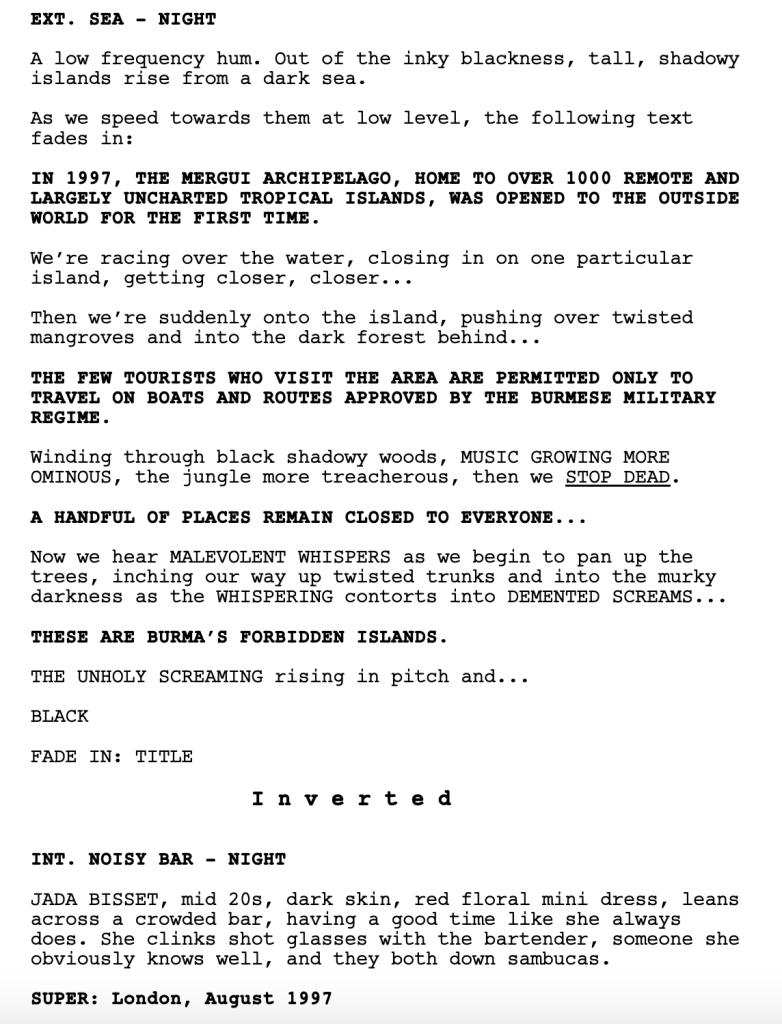

Title: Inverted

Genre: Horror

Logline: It’s 1997 and Jada just wants to have fun. But when the shadowy State of Burma opens its doors to outsiders for the first time, her new boyfriend’s idea of an adventure holiday turns into a horrifying fight for survival as they are stranded on a remote forbidden island harbouring a secret so diabolical, it’s been hidden from the world for centuries.

Title: Kelsey’s Crossing

Genre: Drama

Logline: When the helicopter she’s riding in over the Sonoran desert crashes in Mexico, the racist host of an anti-immigrant youtube channel has to rely on a group of migrants to survive the dangers and brutality of the desert and help her travel 40 miles to get back to American soil.

Title: Ambrosia

Genre: Time Travel/Heist

Logline: Three anxiety-ridden young adults discover an experimental drug that allows them to time travel back 36 hours after each overdose. As the side effects intensify and their tolerance builds, each time travel back becomes reduced (16 hours, 8 hours, etc), but they keep going back anyways to perfect a bank robbery. Meanwhile, the town’s leading detective chases them down.

A funny thing happens when you read a ton of scripts in a row. Especially the way I did it over the weekend. I needed to finish all the entries and I was running out of time since I had to post the semifinalists Monday, so I had zero breaks. As soon as I finished ten pages of one script, I put it in a pile and immediately opened up the next one.

When you’re reading that much, an almost “Matrix-like” clarity comes over you about what really matters in the first ten pages (and, by extension, the script). I realized that all I cared about were two things. One, give me an entertaining scene that grabs me. And two, introduce me to somebody I care about. If you do one of those two things, I’ll read on. If you do both of those things, I’m *excited* to read on.

Let’s unpack this because we talk about these things all the time, but I’m not sure everyone knows why they’re important other than they hear people like me say they are. Too many screenwriters approach the craft from a subjective point of view. They think that because they are writing something, the script will automatically be interesting. It is their belief in themselves that guides their decisions.

So, for example, if they like ‘driving and talking’ scenes, they might start the script with a married couple driving and talking and simply assume that because they like that scenario, other people will as well. But two people talking while driving without anything else going on is a poor scene prompt. In all likelihood, it isn’t going to yield an interaction that a third-party (the reader) would enjoy.

The mental shift writers need to make is to stop seeing their script from their own selfish point-of-view and start looking at it from an OBJECTIVE point-of-view. Transport yourself into the reader’s head then ask if what’s on the page is entertaining *to that person.* It is from this perspective that you will more likely generate a strong scene.

From there, you either come up with a new, more entertaining scene prompt, or you can reimagine the current scene in a more entertaining way. The best way I’ve found to do this is to inject a problem into the scenario. A problem achieves three things. It forces your characters to act. It forces your characters to make choices. And it creates conflict between characters. Because, often, when two (or more) people are faced with a problem, they have different ideas about how to deal with it. And those ideas conflict with one another, resulting in an interesting dialogue.

So if we’re going with this car scene. What if, instead of them driving in the car, we start with them on the side of the highway, their car having broken down. This is our “problem.” Already, it’s a more interesting situation because we’re curious how they’re going to resolve the problem. And what good writers will do is they’ll add factors that pressure the characters, which make the situation even worse.

For example, if this were a married couple, maybe Doug, the husband, dragged his feet all morning even though, Lucy, his wife, stressed to him how important it was that they be on time today because she has a huge meeting. So they’re already late as it is, and now their car has broken down, and she’s got a huge meeting. Look at how much more interesting the dialogue is getting. He might want to call AAA to get the car towed first but, since she’s in such a hurry, she wants to get an Uber, now! That’s what they’re arguing about.

And we can go even further. Maybe they have a 4 year old daughter they’re taking to pre-school. And it’s burning up outside. And she’s in the back of the broken car and now she’s burning up. And so Lucy is already furious that Doug has put them in this position but now their daughter’s safety is in danger. You can see how introducing a problem and then building little agitators into that problem can take a boring car driving scene and turn it into this intense compelling opening.

I’m not sure writers who see writing through a subjective lens can come up with that scene. It’s only writers with an objective mindset that come up with scenes that entertain others. Now there is a writing philosophy out there that goes something like, “Write whatever you want and, if you like it, others will too.” While I’m not going to completely dismiss that philosophy, it relies more on luck. When you completely dismiss the audience and write for yourself, you tend to come up with blander, less dramatic, more pretentious stories.

And, by the way, you shouldn’t be thinking this way ONLY for the opening. The opening may be the most important scene since it’s the scene that either hooks the reader or doesn’t. But you want to take that attitude into every scene in your script. Ask yourself, is the reader being entertained right now or am I assuming they’re enjoying themselves because I’m writing words for them and I’m a good writer?

The other way to hook a reader is to introduce a character who’s instantly intriguing in some way. They are a ‘hook’ in and of themselves. This is the harder route to go, for sure, because character is the hardest thing to get right in screenwriting. Most characters in scripts read like characters when they need to read like people.

There are lots of theories on how to construct a character that feels real and lively and compelling. But I’ve found the starting point is always a commitment to creating a compelling character in the first place. I know that sounds obvious but it actually isn’t. Most writers come up with an idea, start writing the script, and figure out the characters along the way.

If you want to write a strong character, you must think of them apart from your story. This is how Wes Anderson created one of his most famous characters ever, Max Fischer, from “Rushmore.” He and Luke Wilson started with Max, tried to make him as weird and unique as possible, and only then did they come up with a story for him. I dare anybody to go watch that movie and not come away mesmerized by that character.

So you first have to make that mental commitment. Then use your first scene as a resume that lets the reader know what they’re going to be getting. I have a couple of examples for you. The obvious one is “Joker.” Joker, the movie, doesn’t even really have a plot. It’s just this really weird damaged person trying to fit into society who keeps getting kicked down. And that’s how we meet him. He literally gets kicked and beaten down. You want to keep reading after that opening scene SPECIFICALLY to see what happens with that character.

Another example is Cassandra from the upcoming movie, “Promising Young Woman.” That script starts out with a really drunk woman at a bar who gets picked up by a seemingly cool guy who then tries to take advantage of her back at his place, only for her to reveal she’s stone-cold sober and exposes his motives. This woman goes around doing this all the time. But what really makes her interesting is that she doesn’t know where the line is. Is she a hero? Or is she a villain? That’s when you really get into “interesting character territory,” when the answer to that question isn’t easy.

By the way, you’ll note that both Promising Young Woman and Joker started with entertaining scenes. Joker has his sign stolen that he’ll have to pay for if he doesn’t get it back. And we’re pulled into Cassandra’s situation because we’re worried for her. We see this wounded animal at a bar and think she might be in danger. That’s the ideal way to do it. Start with an entertaining scene AND a compelling character. Those always turn out to be the best scripts.

This topic is obviously more nuanced than 1500 words allow. There are scenarios where two people in a car talking can be entertaining, such as if you have strong dialogue skills able to carry a scene all by themselves. And there’s a discussion to be had about how writing for yourself can lead to some off-the-wall weird stuff you’d never be able to tap into if you’d focused solely on pleasing others. So I’m not saying you have to do it the way I’ve laid out.

All I can tell you after reading that many pages in a row is that the scripts that suffered the most were the ones that started with a weak or common scenario and had bland or simplistic characters. Your two most important components are your story and your characters. If you can’t make either of those pop in the first scene, why would anyone keep reading? This article is a game plan to tackle that. I’ll leave it up to you whether you want to use it or not.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) MEET CUTE, the hottest dating app on the market, brings couples together by giving them their Rom Com moment. When the app’s biggest skeptic, Haley, matches with one of its developers, Russ, their instant connection starts to change her mind.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. Which begs the question. Is there going to be a Black List this year?? There wasn’t a Blood List. It appears that Covid has infiltrated Hollywood’s ability to send out scripts. Does that mean The Last Great Screenplay Contest becomes 2020’s Black List? Lots to figure out in these last few weeks of the year! (edit! My bad. I just learned there was a Blood List. Not sure why nobody told me!)

Writers: Chris and Dan Powers

Details: 109 pages

You may be noticing a trend this week. Easy-to-read genre yesterday. Easy-to-read genre today. Why am I picking easy reads? Maybe because I READ 1000 PAGES OF SCREENPLAYS over the weekend to find my contest semifinalists. These crying eyes needed a break. And they found a couple in the sweet simplicity of slasher horror and romantic comedy. Tons of dialogue. The action paragraphs never extend beyond two lines. It’s sweet screenplay-reading nirvana, I tell you.

Haley is a relationship-phobic producer at a daytime talk show where today’s topic is the new hit dating app, MEET CUTE. Meet Cute’s founder, Keaton, explains that Meet Cute takes all your information, matches you up with the perfect person, and then looks for opportunities when you’re in the same area to send you a push notification to “go to the grocery store” or “take a walk in the park.” You then, hopefully, bump into your significant other in that perfect movie-like way.

We then meet Russ, a coder at Meet Cute, and also a user! On Thanksgiving, Russ gets a notification to “go to the grocery store” and, wouldn’t you know it, he meets none other than Haley there. The two have a canned cranberry-sauce inspired “meet cute” and meet again a few days later at the movies, where they officially enter into the first stage of a relationship.

OR DO THEY!?

Out of nowhere, Haley gets the relationship jitters and pulls out.

OR DOES SHE!?!?

No, because Russ tells her, you can’t do that. We’re a great match.

BUT ARE THEY!?!?!?

No! Because guess what? Russ goes into the Haley’s profile to learn that she was not told to go to the grocery store that night. She was supposed to go to the park! Which means they aren’t really each other’s “meet cute.” Russ decides not to tell Haley this so that their relationship can grow. But then, via circumstances that felt suspiciously like ESP sent from the writers themselves, Haley starts suspecting something is off. She charges to Keaton’s place and demands to know their “meet cute” details. Her suspicions turn out to be correct as Keaton confirms they weren’t supposed to meet each other.

Convinced that there’s no reason to continue this sham of a relationship (because she was told by an app that she didn’t like a guy???), Haley bails. Russ bombards Haley with texts but Haley is having none of it. Will Russ figure out a way to convince our app-influenced rom-com princess to change her mind? Or was their “meet cute” destined to become a “separate ugly?”

Wow.

Where do I begin with this one? Well, the dialogue was pretty good. It wasn’t great. But it was better than the dialogue I read in most amateur romantic comedy scripts. One thing I want to point out with rom-com dialogue is that too many newbie writers write the “falling in love” part of the main couple’s dialogue with a lot of agreeing. “I love this.” “I love it too.” “We were at Pepe’s Pizza last night.” “Oh my god! Did you order the Sicilian crust?” “Yes!” “I love the Sicilian Crust!” “Tell me about it!” Don’t do that. Good dialogue comes from the disagreements. It comes from the no’s. The resistance. The conflict.

Here’s simple exchange between Russ and Haley. RUSS: “My dream is to make a pie that’s half pumpkin and half apple. Like a pizza with split toppings.” HALEY: “That’s disgusting.”

This might seem insignificant. But it’s important to note that a lot of newbie writers would’ve had Haley respond, “Oh my God. That’s genius!”

The bigger point is, the dialogue is solid in this script. And I have a feeling that that’s the reason it made the Black List.

Unfortunately, the rest of the script isn’t up to par. The thing that frustrated me most was loading a huge plotline on top of a very weak plot point. A little past the midpoint, we learn that these two aren’t each other’s “meet cute.” And it’s framed as this devastating development. Haley immediately breaks up with Russ over it.

There are two types of ways you can go in your story. There’s MOVIE LOGIC. And there’s THE TRUTH. You want to use the truth as much as possible. You want to stay away from movie logic as much as possible. Haley breaking up with Russ because they aren’t truly each other’s “meet cute” is one of the most movie logic things I’ve ever read. It is the opposite of what would truthfully happen. Haley doesn’t even believe in dating apps. Why does she all of a sudden think their word is bond?

But the bigger issue is that the writers then build the rest of the script on top of this weak plot development. It’s one thing to introduce a weak plot point. You can spot these in any movie. But you don’t want to make a bad thing worse. Try to isolate the weak plot point because if you use it as a foundation for more story, every additional development is going to feel weaker than the last one. And this was a big enough issue that it affected my enjoyment of the second half of the script.

But I actually have a bigger issue with this script. It doesn’t take advantage of its concept at all. When you have a fun concept inside of a fun genre, the only thing you should be thinking about is exploiting that genre. And, to me, the best way to exploit this concept is obvious. Once we learned that Russ was a coder for the app, he should’ve been using it to meet and have sex with as many girls as possible. He should’ve been the complex main character – the one doing something bad, who finally meets a girl he likes.

Consider what this new plot point would do for the aforementioned problem I brought up. Now, instead of Haley finding out that Russ isn’t her “meet cute,” Haley finds out that he’d been specifically writing code to hook up with as many girls as possible through the app. You see, when an obstacle enters your character’s path, you want that obstacle to be as difficult to overcome as possible. That’s why the reader keeps reading. Because they don’t know if the character can actually succeed. If this happened with Russ, we’d genuinely wonder if these two were ending up together. That’s how difficult that realization would’ve been to overcome.

I don’t know why they didn’t do this because it’s so much better than the script we got but I have a theory. Writers are so paranoid about writing “unlikable” characters that everybody has to be perfect! Even the characters with flaws, like Haley and her commitment phobia, are perky and fun and funny. Nobody has any darkness. Nobody has any complexity. We’re all shiny happy people here.

I’m sorry. But shiny and happy is boring. You gotta inject a little darkness into these happier genres to make them pop.

I don’t know. Maybe that’s just me. But this was way too generic for my taste. A great comp to show how to do it right is Voicemails For Isabelle. That script wasn’t afraid to get a little dirty.

Anyway, this is a no for me guys. Hopefully we’ll find a winner next week!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: People, “let’s” means “let us.” Otherwise, it’s “lets.” I can’t tell you how often I run into this mistake.