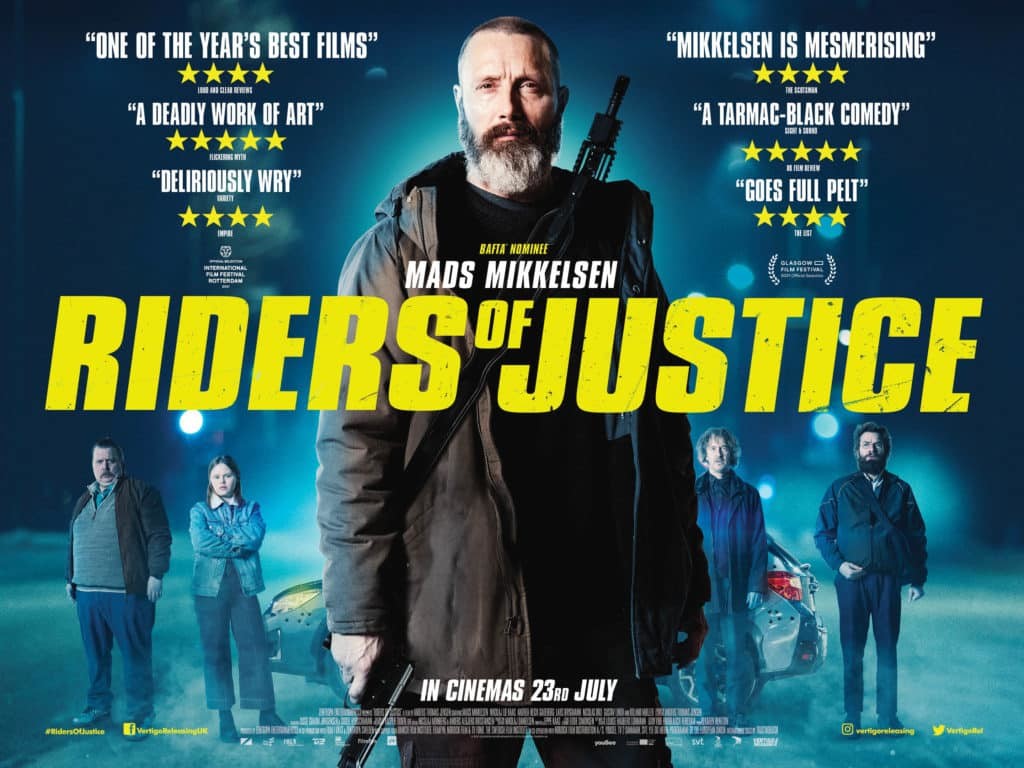

Today’s film will end up in my Top 10 movies of the year, maybe even my top 5!

Genre: Thriller/Drama/Comedy

Premise: After a highly volatile army general loses his wife in a subway crash, a trio of mentally unstable men come to him with evidence that the crash was orchestrated by a criminal organization known as the Riders of Justice.

About: Nikolaj Arcel and Anders Thomas Jensen have written a ton of screenplays together. Anders has something like 25 feature credits. I guess they write and make movies a lot faster in Denmark! Star Mads Mikkelsen has worked with Jensen a number of times. Here’s Mads’ insight into their most recent collaboration process: “As far as I remember, I think Anders Thomas pitched both the story and the idea of morphing his two dramatic universes together: his own “insanity world,” and his more [straightforward] writer side, which writes dramatic things for others … Normally, he pitches me his stuff, and if I call him and say, “What the f**k are you doing?,” then that’s a good sign. Because it’s always insane, what he’s doing, and if I’m on board it gives him the confidence to continue writing.” Riders of Justice is currently a digital rental so you can watch it right now!

Writer: Nikolaj Arcel and Anders Thomas Jensen

Details: 2 hours long

I, of course, could’ve gone and seen “Old” this weekend.

The reason I didn’t was because I could’ve written that review without seeing the movie. I already know what’s going to happen. I know Old is going to be sloppy. I know it’s going to be inadvertently silly at times. I know the last 20 minutes are going to be terrible and not make sense. I know I’m going to get triggered about how someone as untalented as M. Night was able to pull the wool over everyone’s eyes for so long and make a living in this business. I’ve written that review a dozen times already. Nothing ever changes with Night.

Conversely, Riders of Justice may be the most unpredictable movie of the year. You have no idea what’s coming next. Not only that, but everything about this movie screams “This shouldn’t have worked.” The main character is aggressively unlikable. The tone of the movie shifts wildly between dead serious and sitcom-level broad. It’s weird. It’s unruly. It’s unconventional.

I love when scripts take big risks that shouldn’t have worked and somehow make them work because those are the scripts that have the decoded matrix within them. If something works that shouldn’t have, there’s some insight into the fabric of storytelling we don’t usually get.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the story. A teenage girl, Mathilde, and her mother, are riding a packed subway car. Otto, an odd man who uses extreme mathematical equations to predict car accidents, has just been fired from his job. Still, he offers the mother his seat. After she sits down, a sheet of metal from another train slices through the side of the train, killing everyone who was sitting on that side, including the mother (Otto and Mathilde survive since they were standing).

Markus, an army captain currently on duty, gets the call that his wife has died and flies home. Markus, who’s consumed with violence and anger issues, has a terrible relationship with Mathilde. This should be a time of togetherness. But he and his daughter seem as distant as ever. They are soon visited by Otto, who’s been studying the train crash. His computer model has discovered that this was not an accident, but rather a hit. A gangbanger who was also sitting on the fatal side of the train was about to name the Riders of Justice gang in court for a series murders. So the Riders of Justice had the other train deliberately crash into this one to kill him.

A furious Markus is now determined to kill every single member of the Riders of Justice, something he can’t do without help. So Otto enlists his buddies Lennart (who’s spent a large amount of time in a mental hospital) and Emmenthaler (an overweight OCD hacker with anxiety and depression) to help find each of the members and kill them. Of course, when the Riders of Justice figure out what’s happening, they take the fight to our motley unorthodox crew instead.

One of the hardest things to figure out about this movie is how a main character THIS UNLIKABLE could work. We talk all the time about how important it is to make a character likable because if the audience doesn’t like who’s leading them on the journey, they’re not going to care about the journey. And they certainly aren’t going to care whether the hero succeeds or not.

Markus shouldn’t have worked. He’s not only an asshole (one of the first lines we hear from him after he gets home from the mother’s funeral is to tell Mathilde that she needs to work out so she doesn’t get fat) but he doesn’t talk a whole lot. When someone’s an asshole and ALSO doesn’t say much, it exaggerates the assholeness. We’re not able to get inside their head to understand why they’re an asshole, so the fact that Markus just stares forward angrily all the time makes him even more unlikable.

So why do we still care? Why do we root for Markus?

Well, when you have an unlikable hero, it’s critical that you incorporate something called OFFSETTING. Offsetting is exactly what it sounds like. You come up with a bunch of things to offset the hero’s negative disposition. For starters, Markus’s wife was just killed. We’re always going to feel sorry for a character who’s just lost someone.

Markus is active. Audiences love active characters. They love characters who go after what they want. The more aggressively they go after it, the more we tend to like them. As soon as Markus realizes that his wife was murdered, he goes into Active-Mode. It’s time to kill the Riders of Justice.

Audiences also like characters who are good at what they do. There’s a scene early on where Markus goes to ask their first ‘person of interest’ what they know and the guy sticks a gun in his face and tells him to leave. Markus doesn’t say anything, lets the guy close the door on him, walks back to his car, and then, out of nowhere, he spins around, walks right back up to the door, knocks, and when the guy opens the door with the gun, Markus executes a blink-and-you-miss-it takedown of the guy, snatching his gun away then shooting him in the face. It’s not only an intense scene. It shows how skilled Markus is. After that moment, we think, “Yeah, I’m glad this guy is on our side.”

Another thing I noticed Jensen do was he offloaded more screen time than normal to the other characters. Riders of Justice is more of an ensemble piece than a “John Wick” style revenge movie. The reason why that’s important is because all of the other characters are interesting and positive and cool and fun. So we’re not stuck, 90% of the time, with this dreary angry man. That’s a big takeaway for me. If you have an intensely negative hero, consider making your script more of an ensemble piece.

The other thing about this script that shouldn’t have worked was the tone. On one side, you had Markus living in the most extreme intense dramatic movie you could imagine. While on the other side, you had Denmark’s version of Larry, Mo, and Curly.

There’s this whole subplot whereby Mathilde insists that her father see a psychiatrist for his anger issues and when she catches him talking to Otto, Lennart, and Emmenthaler in their barn, the four of them freak out and lie to Mathilde, telling her that they’re Markus’s new psychology team, here to make him better. They’re going to be sticking around for a few weeks and working with him 24/7. At one point, the ruse goes so far that Lennart, who, remember, is certifiably crazy, pretends to be a psychiatrist and does a therapy session with Mathilde. I mean that’s a scene you might see on Modern Family.

It took me a while to figure out how they made this work. Because this is the kind of thing I routinely rip screenwriters for – jumping back and forth between wildly different tones. What I realized was that these three characters weren’t just wacky to be wacky. As the movie goes on, we get into all of their backstories, which inform us why the three of them are so broken. In other words, their psychosis is anchored in reality. It’s not like Jensen said, “Eh, let’s just make him a goofball hacker and have him say funny nonsense.” This hacker has led a tortured life, as have the other two.

I still don’t think many writers could’ve pulled this off. But the ones who can are the ones who build up those backstories so that the “crazy” characters’ lives are based in some level of reality.

In the end, the thing I liked most about this script is that it morphed into this unexpected family movie. All these weird people were living together under one roof. And despite being the most unlikely family ever, they managed to make it work in a weird way. There was something sweet about that. And I don’t think I’ve ever used the word ‘sweet’ to describe a John Wick style premise. Riders of Justice shows you how to subvert expectations THE RIGHT WAY. If you liked Parasite, you’ll definitely like this.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Always try to link your hero’s journey to what you’re personally going through in life at the moment. It will instantly add depth to them. Here’s Anders on how he came up with the character of Markus: “It started with me having this completely normal 40-year crisis that all men have where you look at your kids, you look at your life, and you wonder, “How did I get here, and did I do enough?” You start rebuilding, you start looking forward, and you start looking for connections that will give your life meaning. That’s basically Markus’ character, a guy with PTSD returning home who’s lost faith in everything but needs to find a way to move forward in his life. Of course, it’s highly dramatized, but the core is very personal for me.”

What I learned 2: Anders is okay with ditching outlines if the script calls for it: “Normally, I’ll put a structure up on the wall then write a script from that. But with a script like this, it was a gut feeling. Especially in this film, it had to be a gut feeling. You had to get around so many characters and themes and layers, and if you put that up on the wall, it becomes somehow schematic. You can see the technicality of it. People in film schools hate when I say this, but it’s not something I can teach anyone.

SCI-FI SHOWDOWN REMINDER

What: Sci-fi Showdown

When: Entries due by Thursday, September 16th, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

How: Include title, genre, logline, Why We Should Read, and a PDF of your script

Where: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com

In honor of Neil Blomkamp’s newest movie trailer and Sci-Fi Showdown, we are going back to one of the best science-fiction movies of the 21st century. Here’s what I wrote back in 2009 after I saw District 9: “Today, I went to see District 9. Even after all the hype, I still walked out amazed. We’re looking at the next James Cameron here. Sci-fi like this has never been done before. Within two minutes I actually believed this was happening – that aliens had landed on our planet.”

I think I may have invented the phrase, “This didn’t age well” with that take. It’s hard to put your finger on why Blomkamp fizzled. There’s no question he’s an insanely talented guy. I think part of the problem was that he never put as much effort into the mythology of his subsequent films as he did District 9. The guy is a director, through and through. But he’s never been a great writer.

District 9 feels like a dozen people sat around a room for a year and discussed every single detail about what this world would be like. You need that with science-fiction. You try to cut corners on mythology and your movie can go from deep to thin in a millisecond. We saw that with his follow-up film, Elysium, where you got the sense that Blomkamp wrote the script in a weekend.

But we still have District 9, which is a sci-fi classic. And Blomkamp is even talking about a District 10, which I’ll be first in line for. In honor of everything Blomkamp, here are 10 screenwriting tips from District 9!

1) The hunter becomes the hunted – One of the best ironic situations to place your hero in is to start him off as the hunter and then turn him into the hunted. Audiences LOOOOOOVE that. Why? Because everybody loves irony. To emphasize how effective this is, imagine if Wikus doesn’t work for the organization moving the prawns out of their homes. Imagine if he’s just some street food vendor who turns into an alien. It’s not nearly as exciting of an idea, is it? That’s the power of irony.

2) The Goal Before The Goal – A lot of writers make this mistake. They focus on the main character’s primary goal only. In this case, it’s for Wikus to figure out how to turn back into a human. But there’s often a period of time in your story before the main character is presented with a goal. In that case, if possible, you want to insert a goal BEFORE the goal. That way, your movie gets going right away. What Blomkamp does is he creates this storyline where South Africa has decided to move all of the aliens to a new location. This act of moving them creates a purpose for the story before our real plot begins.

3) Characters should always have something to do – When characters don’t have something to do, the story comes to a standstill. But it’s important to know the difference between the good something to do and the bad something to do. That difference lies in the goal being PLOT RELEVANT. A hero who’s going to get a coffee is NOT DOING ANYTHING. A hero meeting a hitman at the coffee shop to discuss killing his boss – THAT’S DOING SOMETHING. Whenever your character is doing something that’s pushing the plot forward, they’re doing something. Otherwise, nothing’s happening in your screenplay.

4) Don’t roll out the red carpet for your hero. Put up a barbed wire fence instead!!! – A classic beginner mistake is rolling out the red carpet for your hero’s interactions. Whatever he needs to do, it goes off without a hitch. It should be the opposite. You want to put up a barbed wire fence. Make it difficult. Especially in sci-fi movies where the stakes are high. Go and watch the sequence where Wikus tries to move the prawns from their homes. Literally every prawn gives him trouble. There isn’t a single house where the process goes smoothly. Fences create conflict. Red carpets create boredom.

5) Documentary/fiction hybrids are a cheat-code for exposition – One of the hardest things to do in sci-fi is manage all the exposition and convey it to the reader. Any sort of story with an interview component, such as a documentary, lets you bypass that. District 9 may be the most exposition heavy science fiction movie ever. But I bet you never thought about that until I just mentioned it. That’s because its exposition is hidden inside documentary interviews, so we never consider it exposition.

6) A line of suspense can add an extra level of intrigue to your story – All suspense is is hinting that something bad is going to happen in the future. You can use it, then, to increase the level of interest from the audience. All throughout the opening of District 9, we get these interviews of people talking about Wikus, but they’re doing so as if something terrible has happened to him. “Wikus was always such a kind boy,” his mother tells us. We now know that something bad is going to happen to Wikus, which increases our interest in sticking around. You could, of course, not have shown any of those interviews. But, by omitting them, you also omit a line of suspense that’s driving the reader’s interest.

7) Use language differences to create more interesting dialogue – All of the dialogue between Wikus and the aliens – whether he was trying to evict them or, later, when he’s asking them for help – was charged. It had a heightened unpredictable quality to it. I finally realized it was because Wikus never entirely understood the alien language. He grasped pieces of it, enough so that he could communicate with them. But because he couldn’t speak it fluently, he was always playing catch up. It was a major reason why all the scenes with him and the aliens were so good, that struggle to understand each other and the messiness that brings. I’m thinking you can do the same with any two characters who don’t speak the same language. You can use their misunderstandings and assumptions to create a more interesting interaction than if the two are able to communicate exactly what they’re thinking. Remember, with screenwriting, you’re always looking for ways to make things harder on the characters. Not being able to understand one another is a simple way to make things harder. And, as a bonus, it makes the dialogue better.

8) Your story’s theme and your main character’s flaw are almost always tied together – District 9’s theme is: don’t treat people differently just because they don’t look like you. And Wickus’s flaw is that he doesn’t treat the aliens like real “people” because he doesn’t see the aliens as real “people.” We see this when he’s tossing cat food at them and talking to them like babies. Only when he becomes an alien and sees others treating him the same way he treated the aliens, does he realize his mistake and change.

9) What’s the worst thing you can do to your character right now? – This is a great question that can lead to some great moments in your script. It’s not something you want to use in every scene. But it’s definitely something you want to use occasionally. When Wikus gets home after his long day at work where he’s ingested some strange chemical and has been throwing up the rest of the day, feeling sicker and sicker by the minute, Blomkamp could’ve easily had his wife waiting for him, notice that he’s acting strange, ask him what’s wrong. But that would’ve been a forgettable scene. Instead, Blomkamp asks, “What’s the worst thing I can do to Wikus right now?” And the answer was… give him a surprise birthday party! All Wikus wants to do is rest. He’s sick and getting sicker by the minute. Instead, he has to be happy and peppy and act like nothing’s wrong for the next couple of hours – his worst nightmare.

10) 99% of thriller scripts fall apart when they devolve into an “on the run” story – This is because most scripts go from a STRUCTURED STORY to, all of a sudden, the main character is running around like a chicken with his head cut off, his only goal to stay a step ahead of the bad guys. This trope is boring to watch because all ‘on the run’ stuff feels the same. To combat this, give your character targeted clear goals they’re trying to accomplish. These goals will bring structure back into the story and give it purpose. You can have them run for a few scenes. But then it’s time for them to come up with a plan. Wikus goes back into the Prawn Camp because it’s the only place where he can hide from the authorities. He then agrees to help the alien get his ship operational with the understanding that, when he does, he’ll turn Wikus back into a human. This is a way more interesting storyline than had Wikus just run around Johannesburg for two hours.

Hold on. Don’t tell me you’re sending your script out there without getting professional feedback first. You only get one shot with these industry contacts, my friend. Don’t screw it up by sending them the 10,000th average screenplay they’ve read this year! I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested. Use code phrase ‘WARM IN JULY’ and I’ll take a hundred bucks off a pilot or feature consultation. As long as you pay in July, you can send the script to me whenever it’s finished. Chat soon!

It’s the Back to Back Battle of the Airplane Scripts! Who will win? One of the most successful authors ever or a first time Black List writer?

Genre: Mystery

Premise: During a Chinese flight that experiences massive turbulence, three people die. A young investigator for the company that built the plane has less than a week to figure out what went wrong.

About: The deal Michael Crichton made for the film rights to this book were, at the time, the most expensive ever, at 10 million dollars. You’d think if someone paid that much, the movie would’ve gotten made, right? I guess Crichton kept vetoing the scripts, which he had the power to do. This version of the script was written by Frank Pierson, who wrote and directed the 1976 version of A Star Is Born. That was a very big time in Pierson’s life as, just a year earlier, he’d written Dog Day Afternoon (“ATTTTTTIIICAAAAAA!!!”). Alas, Crichton seems to have been unimpressed. Will we be?

Writer: Frank Pierson (based on the book by Michael Crichton)

Details: Sept 21, 1998, 127 pages

I asked you for plane crashes, you gave me plane crashes!

Thanks to everyone who e-mailed, sending me scripts, loglines, and articles to all the plane crashes. Still have to get through all of them. You see, I stopped when resident 90s script expert, Scott Crawford, sent me Airframe.

I’d never even heard of Airframe. And I’m someone who was once a Michael Crichton aficionado. I was even one of 14 people who read that book of his about nanobots! For those of you young’uns, there was a time when Crichton was the biggest idea-man in Hollywood. We’re talking about the brain behind Jurassic Park. Everything he wrote turned to diamonds.

Crichton and an airplane disaster sound like the perfect marriage. Let’s find out if the two lived happily ever after.

Casey Singleton gets a call that a plane heading from Hong Kong to the U.S. made an emergency landing in Los Angeles after experiencing thunderous turbulence. The turbulence was so bad, in fact, that 3 people died and dozens more were injured. Although this was a Chinese airline, TransPacific Air, it was an American built plane from Norton. Casey is the head of the investigation team at Norton.

As soon as the plane is cleared, Casey brings her team on to see the destruction inside. Seats have been flattened as if a giant stepped on them. There’s blood everywhere. The main cabin is a disaster area. There’s even a body that went halfway through the ceiling that’s still lodged up there (wear your seatbelts everybody!).

The investigation quickly centers on a design flaw that may have made the wing’s flaps deploy mid-flight, which would’ve sent the plane tumbling around in the air like a drunk uncle. The reason this flap issue is so important is because the president of Norton, a guy named Jon Edgarton, has a deal with the Chinese to send 50 more of these planes to them next week! So not only do they have to figure out what went wrong. They have to convince the Chinese it was a freak accident.

Meanwhile, a video tape from INSIDE THE PLANE somehow starts getting circulated around town and the rumor is that whatever’s on that video is gnarly. If that tape somehow makes its way to the news, the company is doomed. When Casey finally sees the tape, she’s horrified. It shows in graphic detail all the chaos that went on while the turbulence was happening. When CNN gets a hold of it as well, Casey will have to use all of her persuasion powers to convince them not to show that tape. Will they?

Sometimes you come up with an idea where the idea itself is the angle. M. Night’s new movie where people age 1 year every hour on a beach is a concept where the angle has been decided as soon as the concept was decided.

Other times, writers are interested in subject matter – say, a plane incident – but don’t yet know what angle they’re going to tackle the story from. The decision you make on that angle will determine whether you’ve got a good idea or a bad one (or something in between).

Crichton, like me, wanted to write a plane story. He just didn’t know what the angle to that plane story would be. He ultimately decided on an investigation angle that dove deeply into the minutiae of an aviation malfunction.

Instead of a big flashy plane crash, this movie is about the little flashing lights in a cockpit that the pilots don’t understand. And the purpose of slats on a wing. And the pounds of force on the human body when a plane is dropping 500 feet per second. And the subcontracting details of allowing China to manufacture the fuselage.

I love specificity in storytelling. One of the biggest mistakes I see amateurs make is telling generalized stories without enough detail. The detail – the specifics of the world you’re exploring – are what sell the story. Airframe is the most convincing fictional story about a plane incident that I’ve ever read. The specificity is exceptional.

But the angle Crichton chose severely limited the concept’s wow-factor. Not everything has to be Jurassic Park. But I’m not sure why Crichton thought 3 people dying from turbulence was a big enough story. Hell, there’s even a moment in the script where a news producer is told about what happened but chooses not to put the story on the air. “Defective parts? I don’t want a defective parts story. I want a death trap in the sky, a flying coffin story.” When your own characters seem to know more about what an audience wants than you, you may be in trouble.

Now *I* thought the story was interesting but, I like I told you yesterday, that’s because I love the minutiae of plane accidents. But I don’t think non plane enthusiasts would give two shits about this angle.

A question you want to be asking yourself with whatever you’re writing is, “Why does this matter?” Why does 3 people dying in a plane matter? Because that’s where the audience’s mind will be. Maybe not consciously. But subconsciously. And when the answer is, “It doesn’t matter all that much,” the audience loses interest. They get bored. They tune out.

It’s a pretty surprising oversight by Crichton, who knows what a big idea is better than anyone.

It’s too bad because this script has some cool stuff going for it. First of all, it’s shockingly timely. The plot is about offloading work to China and China using shady practices that don’t prioritize the safety of their planes. It also has a strong female protagonist, which wasn’t exactly a common thing back in 1998.

They also did something really clever with Casey. Typically, the person investigating the mystery in a movie like this is trying to bring the company down. They’re a journalist trying to expose the truth. What Airframe does is it makes Casey an investigator for Norton, the company that built the plane. So her job isn’t just to investigate the incident. It’s to hide her findings. To protect the company instead of expose it. So everything she finds, she’s trying to keep it from getting out, which is a slightly different, and more dynamic, investigative process than we usually get.

Airframe is even more inside-baseball than yesterday’s plane script. And yesterday’s plane script was about something that really happened! It just goes to show how important research was to Crichton. You got the feeling that this guy knew how many millimeters the bolts were that held the fuselage together. Unfortunately, the script can’t overcome its weak premise. It should be a reminder to everyone that you can write some of your best stuff. But if you’re doing so with a weak concept, it won’t matter.

Script link: Airframe

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A “What the hell are you talking about” character. Whenever you have a subject matter this technical or that requires a ton of exposition, it doesn’t make sense to have characters WHO ALREADY KNOW ALL THE ANSWERS TO THE QUESTIONS THEY’RE ASKING to talk about this stuff. So a trick to use is to add a “What the hell are you talking about” character. His main job is to be the brain of the audience and ask, “What the hell are you talking about?” This character in Airframe comes in the form of Bob Richman, a low-level assistant to Jon Edgarton. Edgarton hands Richman over to Casey so that he always has eyes on the investigation. Richman, who’s clueless about planes, is constantly asking Casey questions like, “Why is it bad for the flaps to deploy mid-flight?” so that the audience can keep up with the technical aspects of the story.

Today, we learn the vital difference between a STORY and a STORYTELLER.

Genre: Drama/True Story

Premise: Journalists race to expose how Boeing knowingly misled regulators, pilots, and airlines to cover up a problematic flight software system on the 737 MAX, leading to two major airplane crashes and the deaths of 346 people. Based on real events.

About: Today’s script comes from an up and coming writer and producer, Terry Huang. This script made last year’s Black List with 9 votes.

Writer: Terry Huang

Details: 105 pages

I used to be terrrrrriiiiffieeed of flying. To the point where, every time I got on a plane, I accepted that it was the end of my life. No, seriously. I’d look back fondly at the things that I’d accomplished. I’d be frustrated at the things that I hadn’t. And then, off I’d go, onto this 200 foot long metal tube that was sure to crash down in a fiery blaze with me inside of it. It was fun while it lasted!

It isn’t difficult to figure out where my fear of flying originated. When I was 8 years old, waiting at the terminal for a red eye flight to a Mexican destination with my family, my mother staged an open resistance to getting on the plane because she had a “feeling” that there was something wrong with it and that it was “going to crash.” Up until that point, I didn’t even know planes could crash! And so my fear of flying began.

The good news is I’m over that fear. Now I just worry about there being enough space for my bag in the overhead.

But due to my history, I’m still fascinated by airplane disasters. I still investigate famous crashes all the time. I’ve probably spent upwards of 30 hours looking into the infamous Tenerife crash (the most deadly crash in aviation history). It’s why I’ve repeatedly mentioned on this site that I’m looking for a killer plane concept to produce (have one? Send me the logline!).

Today’s script covers one of the scariest airplane disaster concepts of all, one that involves pilots doing exactly what they’ve been trained to do, only to have the plane’s computer take over and kill them. Let’s take a look.

60-something Dominic Gates is a reporter for the Seattle Times. In October of 2018, he hears about a Lion Air plane crash in Indonesia that killed all 189 people on board. Specializing in airplane crashes, Dominic starts making calls to his contacts to find out what happened.

Meanwhile, halfway across the country, in the Bloomberg news offices in New York, reporters Peter Robison and Joel Weber also hear about the crash. The plane that went down is something called a 737Max, which is a modified 737 with bigger engines. They immediately call Boeing, who manufactured the plane, to see if they’ve made a statement yet. They haven’t.

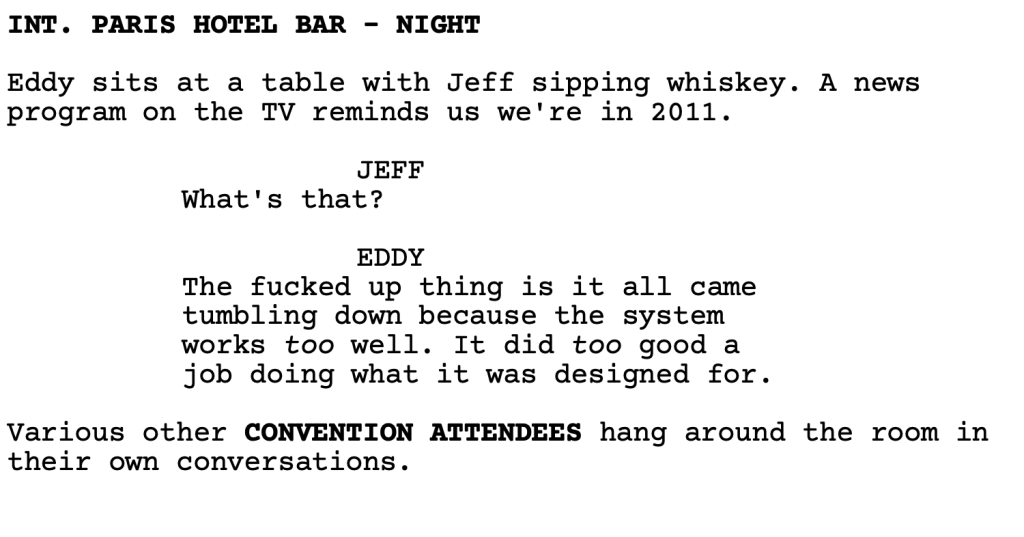

We then hop over to Paris, where plane supply salesmen, and long time buddies, Eddy Knowles and Jeff Spalding, are attending the annual airline industry’s trade show, a place where all the big players, including Boeing and Airbus, are getting ready to promote their latest planes and technologies. Their conversation revolves around the fact that Boeing’s game-changer plane, the Dreamliner, is more like the Nightmareliner, as they can’t get the thing approved to fly. As a result, Boeing’s been forced to improvise, adjusting planes that have already been approved, which has resulted in the 737Max.

We follow the bouncing ball all over the world as we meet people on every side of the issue, from journalists, to pilots, to mechanics, to the CEOs of the major plane companies themselves, all of which heats up when a SECOND 737Max crashes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. What Dominic, Joel, and Mike eventually find out is that when Boeing added bigger engines to the Max, it required them to also add a software system that adjusted the balance of the plane. That software erroneously took over and sent both planes plunging to their demise.

But the real scandal occurred behind the scenes where Boeing deliberately hid mention of this software system in their plane manuals. You may say, “Why would they do that?” It was because the FAA mandated that any significant change in the operation of a plane require training. Training cost money so airlines hated it. Since Boeing knew the airlines wouldn’t buy any planes if significant training was required, they hid the software from the airlines, figuring it would work in the background and therefore no pilots would ever need to know about it. The script concludes by informing us that because Boeing is so important to the economy, the company got off with a mere slap on the wrist for their gross negligence.

As a screenwriter, you are a shaper.

You know the famous scene in Ghost where Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore take a lump of wet clay and slowly mold it into a vase? That’s what you’re doing as a screenwriter. You’re taking a lump (all these ideas in your head) and you’re molding it into a vase (a thoughtful compelling story).

When you don’t do that and you just sort of vomit everything onto the page – throwing clay around willy-nilly, not looking at your creation, checking your phone for messages, flicking the specks of clay on your hands back onto the lump – sure, you’re technically still creating a vase. But there’s no shape to it. It’s just a bunch of clay.

I want you to internalize what I’m about to tell you because it’s important:

Anybody can tell a story. The writer differentiates themselves by being a storyTELLER.

I can get the homeless guy down the street to ramble on for 3 hours about how the bus driver wouldn’t drop him off at his favorite liquor store. That will technically be a “story.” But it’s not a story told well. That’s what the storyteller’s job is. To take all the variables and shape them in a way that the story has form, dramatic value, and purpose.

Otherwise you’re just giving us information. That’s how Single Point of Failure read. We just go from room to room, character to character, telling us new things about the plane crashes. There’s no form to it.

A good example of a screenplay that has form and is somewhat similar to Single Point of Failure is Margin Call. That script is about a giant investment bank that realizes it has a ticking time bomb in its investment software that has a high probability of bringing the entire bank down if they don’t do something about it immediately.

Now you could’ve written Margin Call like you wrote Single Point Of Failure, where we meet all these different players across New York City. A rival bank’s CEO, someone at the SEC, a couple of reporters who get wind of what’s going on and start digging into their story. But anybody can write that. There’s no storytelling to that version.

Instead, writer J.C. Chandor cleverly focuses on a low-level worker in the company who discovers the error. He realizes that they’ve got about 24 hours before this destroys the company. So he brings it to his middle-manager boss. The middle manager then brings it to his boss. That boss then brings it to his boss. Until the climax is them in a meeting with the head of the company. The story has a clear design to it that’s been carefully shaped.

Meanwhile, Single Point of Failure feels like its scenes were generated in a randomizer. I always get nervous when every scene introduces a new character, which this does. That tells me that the writer isn’t thinking his story through. You’ve got all of these characters you’ve already created. Why not craft a story around them as opposed to throwing new character after new character at us? It’s because coming up with a story is harder. And we’re all inherently lazy and prefer to take the path of least resistance. But if you want to be a good screenwriter, that’s what you have to do.

But guess what?

I still liked Single Point of Failure.

A lot of that is because I like getting into the nitty gritty of why airplane crashes happen. So this whole script was basically catnip to me. And I was rewarded for my curiosity. I learned some things – such as Boeing deliberately hiding the 737 Max software in their manuals – that I didn’t know before.

Also, one of the necessary ingredients of a true story like this is that it makes you mad. If you’re mad, it means you’re emotionally invested. And while I’d rather be happy at the end of a movie than mad, I’d also rather be mad than have no feelings whatsoever. And this story makes you mad. You can’t believe that a corporation this big with this much responsibility would do something that put so many people in danger. It’s infuriating.

A Single Point of Failure is a plane crash geek’s version of Spotlight. If that sounds like something you’d be interested in, check it out!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m going to give you at least one scene of good dialogue in your next screenplay. It’s called doggy bag dialogue. Doggy bag dialogue is any interesting piece of information relevant to the scene or broader story that the reader can take home with them. Single Point of Failure has a good one. This doggy bag dialogue occurs when Eddy explains to Jeff why Boeing’s MCAS system actually works *too* well.

Is Space Jam 2 secretly a great movie??? Why did Black Widow drop so much in its second weekend? Has Cannes ever given the Palme D’or to a good film?? And Carson offers a book recommendation!

Out of morbid curiosity, I threw on Space Jam this weekend. It was on HBO Max 4 free so why not? My enjoyment of the film, if you can call it that, was inconsistent at best. There is only so much fun an adult can have with a movie that’s made for 11 year-olds. But when I turned off my brain and leaned into that kid who thought Saturday morning cartoons were the coolest most awesomest things that life had to offer, I enjoyed myself.

But I’m not here to review the film. I’m here because I had an epiphany while watching the movie. Are you ready for it? Here it is: Every screenwriter should write at least one family movie. Even if you never show that script to anyone, you should still write it. Let me explain why.

A family film allows you to practice executing all of the big screenplay beats without fear of overdoing it. Since family films are not put under the same microscope as, say, a David Fincher movie or a Noah Baumbach film, you can practice all of the things you’ve learned on screenwriting websites without having to worry about being too on-the-nose. That’s because kids movies ARE on-the-nose.

Take, for example, the hero’s arc. This is the most classic story beat there is. You have a main character. They have some sort of problem in their lives holding them back. The journey they go on is about realizing why this issue is hurting them, and ultimately learning that there’s a better, more fulfilling, way to live life. This transformation – or “arc” – leaves the audience feeling happy because they, too, have issues holding them back. They feel that if this movie character can overcome their flaw, they can overcome theirs as well.

But a character arc is quite a delicate measure to pull off. It looks easy when it’s done well but there are a lot of places where you can screw it up. A common issue is that the writer will say, “I don’t want to overdo it,” and be reallllllyyyyyyy subtle in how the flaw plays out. They’ll hint at it on page 30, hint at it again on page 50, before finally having them overcome it during the climax. When the reader asks, “What was that whole thing at the end where the hero said to his daughter he was going to donate his life savings to cancer research?” The writer replies, “It’s because he’s no longer greedy! The hero finally realized that money isn’t what matters. It’s family!” The reader responds with a side glance. “The hero’s flaw was that he was greedy?” And the writer dies a little inside.

The great thing about kids movies is that you can lean into this stuff and not worry about it coming off as corny or on-the-nose. In Space Jam, Lebron James’s son doesn’t want to be a basketball player. He wants to make video games. Lebron can’t accept that his son doesn’t want to play basketball and keeps pushing him to ditch the computer and practice his jumper.

After Lebron gets sucked into the Toon world, where he and the “Toon” squad are up against the “Goon” squad, Lebron keeps telling his teammates what to do. Move the ball up the court quickly. Set picks here. Step back, crossover when the other player is too close. Dunk. Etc. The results are not good. By halftime, they’re down 1000 points.

Lebron asks the team what’s up? Why are you playing so bad? They concede that they’re doing what he told them to do – be like him – but it’s not working. Lebron has his big epiphany. Just like with his son, everybody here has their own talents. He can’t make them be like him. He has to let them be themselves. Lebron has arced! And, of course, once the toons can start doing toon things (Roadrunner painting a fake desert canvas that the Goon players disappear into) they start winning.

Now some of you may be rolling your eyes. “SOOOOO ON-THE-NOSE. SOOOOO CHEESY.” That’s the point. You can’t learn to execute a flaw subtly if you’ve never executed a flaw effectively in any situation. This holds true for all the big screenplay beats: the inciting incident, the refusal of the call, the fun and games section, the midpoint escalation, the central relationship conflict, making the final goal seem impossible. When you write a children’s movie, you get to master all this stuff without the cynical rolling eyes of the high-expectation moviegoer.

Every genre has a slightly different expectation when it comes to screenplay beats. The kid’s movie is on-the-nose. The buddy-cop movie is a still on the nose but a little less so. The serious action movie, like Jason Bourne, is more subtle still. All the way up to Oscar dramas, where the goal is to camouflage your screenplay beats to such a degree that the audience is unaware that the movie was even written in the first place.

So go write that family film. The good news is that if it’s actually good, it’s one of the most profitable genres in the business. So you could get paaaaaaaaaid.

Moving along, Black Widow did not do well on its second weekend at the box office, dropping a widow-making 67%. For some reference, the last Marvel movie to be released, Spider-Man: Far From Home, dropped 51% on its second weekend. If we want a closer comp, we can use Captain Marvel, which dropped 55%. The reason 55% is so concerning is that Captain Marvel was a brand new character. Black Widow is a known character who had been around for a decade. If anyone should have the lower drop, it should be the proven character.

What does this mean? Hard to tell. Everything in the post-pandemic box office world is hard to gauge. Who knows how many people are buying the movie from Disney’s “Premiere Access” service. To be honest, as I’m writing this, I’m not even sure if they’re including the money they got from Disney + in that final box office haul or not. If it is included, that means even fewer people went out to watch the movie.

I did hear something interesting about Black Widow from Half in the Bag’s review this week where they said Marvel starts creating their action set pieces before the director has even been chosen. I don’t know how accurate this information is and I’m sure it differs from project to project. But it would certainly explain why Black Widow’s set pieces felt disconnected from its family-oriented storyline, which I found to be pretty good.

I’ve actually wondered this for a while. How is it that Marvel is recruiting these directors who have never shot an effects shot in their entire careers, and putting them in charge of action set pieces that, individually, cost ten times as much as the most expensive movie they’ve made? I guess that’s the answer. Marvel says “F U, newbie. We’re going to shoot the action scenes ourselves and you can record your little two-people-in-a-room-talking scenes when we call on you.” I think one of you pointed this out in regards to Eternals. They’re having all sorts of issues balancing Chloe Zhao’s muted heavily dramatic character stuff with the big fancy set pieces. As a result, Zhao has been pushed to the side while second unit directors with more experience finish the movie.

This probably goes on more than we know. We heard this same thing happening all the way back with Rogue One, with Gareth Edwards not being able to handle the grandness of his super-movie. So they replaced him with Tony Gilroy. All of this is a result of Hollywood moving away from bland but experienced directors (aka Ron Howard) to “visionary” but inexperienced directors. These directors bring vision. But never having been on a giant set before or having filmed a giant set piece, they need help. So studios, I guess, have come up with this hackneyed solution to the problem, separating the effects directing team from the film directing team.

I think this is why Kathleen Kennedy loved Rian Johnson so much. She thought she had the best of both worlds. She got a director who has a unique vision who ALSO made enough movies that he didn’t need babysitting. She could just leave him alone to make his movie. Of course, her Rian Johnson beer goggles kept her from realizing he’d written a garbage script. Which just goes to show how difficult making a good movie is. Even when you think you’ve got all your bases covered, you can still make a terrible movie (“Hey, I got an idea. What if we made the most iconic hero in movie history, Luke Skywalker, as unlikable as possible? Who’s with me?”).

Elsewhere, the Cannes Film Festival just wrapped. If you’re looking for movies that are guaranteed to be bad, look at whatever the Cannes Film Festival celebrates. You may say, “Carson, why are you such an indie film hater?” That’s not what this is about. The French Film Industry refuses to put any stock into the trade of screenwriting. Nobody cares about screenwriting over there. All they care about is the director. This is why they celebrate so many movies that are terrible. Because they don’t care if the story makes sense. All they care about is what the film looks like.

Another problem with Cannes is that they hate Hollywood so much that they are determined to celebrate the opposite of whatever comes out of the studio system, even if that means propping up something terrible. It’s more important to NOT be Hollywood then to find actual good movies. To a certain degree all film festivals are like this. Sundance is pretty pretentious itself. But Cannes is the worst.

Now, I will admit they’ve gotten it right a few times. Parasite was amazing. And The Square was pretty cool as well. But they often prop up weird, nonsensical, boring films that are rewarded for things other than storytelling. I don’t know where the word “pretentious” derived from, but I always look at it as a derivation of “pretend.” All of these Cannes films are people pretending to make something profound when, in actuality, once you look past the directing, they’re just as vapid as the worst Hollywood flicks. By the way, how the heck didn’t The French Dispatch win the Palme D’Or? It’s not only black and white (any black and white film entered into Cannes is automatically placed in the Top 5). But it’s got “French” in the title! So disappointed in Wes Anderson.

Let’s end this Mish Mash on a positive note. As you know, I loved Sally Rooney’s Normal People on Hulu. I thought it was excellent. I recently found out the same filmmaking team, including the awesome Lenny Abrahamson, are filming Rooney’s first novel, Conversations with Friends, as a follow-up. So I picked it up and read it. I wanted to see what it was about Rooney’s writing that allowed it to be adapted into something so powerful. And, holy s#%@. I was not disappointed.

Rooney is an exceptional writer. The premise of the novel is simple (you guys know I like simple stories!). A young spoken word poet starts dating an actor who’s married to a journalist doing a story on her. You’d look at that and think, “How do you get more than 50 pages out of that? That’s a subplot for any other novel.”

But Rooney somehow makes it compelling the whole way through.

Part of it is her inherent talent to communicate the complexities of the human experience better than any writer in recent memory. She has these insights into the minutiae of human interaction that are consistently illuminating. You sit there and you think, “I’ve always thought that abstractly but have never been able to communicate it the way she just did.” And she mixes in this deft touch of dry humor every once in a while which turns what should be sad moments into something really funny.

My discovery that I was in love with Nick, not just infatuated but deeply personally attached to him in a way that would have lasting consequences for my happiness, had prompted me to feel a new kind of jealousy toward Melissa. I couldn’t believe that he went home to her every evening, or that they ate dinner together and sometimes watched films on their TV. What did they talk about? Did they amuse each other? Did they discuss their emotional lives, did they confide in one another? Did he respect Melissa more than me? Did he like her more? If we were both going to die in a burning building and he could only save one of us, wouldn’t he certainly save Melissa and not me? It seemed practically evil to have sex with someone who you would later allow to burn to death.

As you can see, her writing is simple. It’s easy to read. As you guys hear me talk about all the time, making your writing easy to read does you so many favors. I’ve come across lots of strong concepts that were ruined by writers who were trying to prove to you that they were Writers with a capital “W.” Rooney reminds us that you can convey everything you need to using simple words embedded in basic sentence structure.

I know she’s not for everyone. I’m not trying to convert anyone here if you’re not into these types of books. But if you liked Normal People and you like good writing and you want to be inspired, definitely check out Conversations With Friends. It’s really good.