We’re keeping it going with Sci-Fi Showdown inspired Thursday articles. Remember, the Sci-Fi Showdown deadline is Thursday, September 16th. You can learn more about it here. It’s absolutely free. So get those sci-fi scripts finished and get them in on time. Let’s make a f%$#ing great science-fiction movie together!

One thing I want to point out before I get to today’s tips. A lot of these tips deal with the chase aspect of the film. But these tips can work for ANY type of chase. A car chase. A foot chase. An across-the-galaxy chase. They can also work within chase sequences. So if your script just has one chase sequence, these tips can be applied to that as well. All right. Let’s get to it.

1) 99% of Sci-Fi Movies require voice overs or a title card at the beginning of the movie to explain what’s going on – If you don’t need a ton of explanation to set up your movie, use a title card. If you’ve got a lot to explain, use a voice over. Fury Road uses Max’s voice over. Star Wars uses title cards. I don’t care which you use but you probably need one. If we don’t know how your world operates, we’re going to have a tough time enjoying what’s happening.

2) Urgency and Sci-Fi go together like peanut butter and jelly – The most underrated reason for Star Wars’s success – and I’m talking the original Star Wars here – is its urgency. Urgency can camouflage all sorts of script problems due to the fact that the story’s moving so fast, the reader doesn’t have time to notice problems. Fury Road doesn’t just embrace urgency. It makes it the driving force behind the entire story. The bad guys are always right behind them. There’s never time to slow down.

3) If you’ve got two protagonists, don’t let your first act get bogged down setting those protagonists up – Fury Road has two heroes, Max and Furiosa. Had they written this script traditionally, they would’ve spent the first 30 pages of the script setting both Max and Furiosa up before we went on the journey. Director George Miller knew that’d be a dumb idea in a movie built around urgency. So he chose to set one character up before the chase (Max) and the other character up during it (Furiosa). Too much setup can lead to boredom which is why saving some character setup for the journey might be a good option.

4) Why limit yourself to two sources of conflict when you can have three? – With one hero, you get internal conflict (the battle against one’s self) and external conflict (the battle against the antagonist). With two heroes, you get those things along with a third element of conflict – inter-relational conflict (the conflict that occurs between the two main characters). Since a good argument can be made that the more conflict there is in your story, the better, consider allowing two heroes to lead your movie instead of one, like Fury Road.

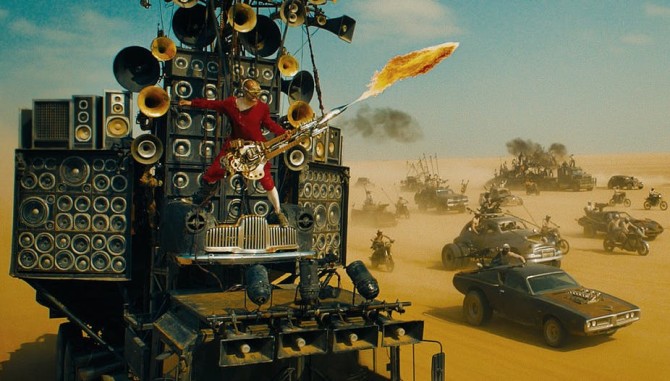

5) Your sci-fi movie *must* have original ideas! – If you’re not bringing any original ideas into your science-fiction film, don’t bother writing it. Sci-fi is a genre where a heavy expectation is placed on creativity and imagination. That means you’re going to have to take some risks and make some non-traditional choices. In Mad Max Fury Road, there is zero reason for Immortan Joe to create a big crazy theatrical chase team that consists of fireworks and dudes playing electric guitars on an 80 mile per hour stage to chase Furiosa. In fact, it’d be a hell out of a lot smarter to jump in your fastest cars and chase Furiosa that way. Yet that is exactly what separates this movie from every other sci-fi movie, is the theatrical nature of the chase. What choices will you make that set your sci-fi script apart?

6) In chase movies, you want to put your character in a lot of a situations where going forward is HARDER than surrendering – Too many screenwriters treat their on-the-run protagonists like little children that need to be coddled and helped. That’s the opposite of how you should treat your protagonists. You want to place your protagonists in situations where surrendering to the bad guys is the better choice. They famously did this in Empire Strikes Back when Han Solo decides to fly into a mine field to escape Darth Vadar, despite the fact that there was an infinitely higher chance he would die in the mine field. Same thing here. Furiosa sees the mother of all sandstorms ahead of her. Surrendering would be the better choice in this situation. Which is why we get so excited when she chooses to keep going.

7) Silent Characters work much better on screen than they do on the page – Mad Max in Fury Road, much like Mad Max in the original Road Warrior, doesn’t say a whole lot. While this can work great onscreen with a strong actor and strong director, it’s something I’d be wary about doing in a spec script. Unless your silent hero is EXTREMELY ACTIVE and always charging forward making bold choice after bold choice, he’ll likely disappear on the page. I’ve read lots of scripts with quiet protags and, I can promise you, those characters rarely make an impact. The difference with something like Fury Road is that the director is writing the script. So he doesn’t have to worry about any characters not working on the page as long as they work onscreen.

8) Fast movies need quick flashbacks – For the 217,000th time, don’t use flashbacks to begin with. But if you do, use them sparingly and with purpose (they must be necessary, not exposition-dumps). In action movies, you can use flashbacks, but do so in the spirit of the genre and be quick about it. Max has this backstory where he got a girl he was protecting killed. We get a good dozen flashbacks of this throughout the movie, but they’re very quick – 2 seconds or less. All that matters with backstories is that we understand them. So if we can understand them in 2 seconds, you’ve done your job.

9) – Mythology tends to work best when it operates in the background, not when you shine a big light on it and say, “Look at what I did.” – Science-fiction writers tend to love their mythology (the inner workings of their fictional world) so much that they constantly halt the movie so that their characters can talk about or exhibit aspects of that mythology (see Matrix: Reloaded). What’s so great about Mad Max Fury Road is that most of the mythology is background noise. There are these pale soldiers. They seem to have some sort of blood disease. They have their own language, their own chants. There’s a specific moment, during an intense part of the chase, where one of them sprays some crazy drug-foil all over his face, he screams out a well-known chant to the others, before leaping onto the enemy car with explosives, destroying it. There were so many little moments like that that only the pale soldiers understood – and Miller never stopped to explain all of it. It was always happening in the background.

10) Someone in your movie’s got to arc, dammit – Some serious directors and writers consider character arcs unrealistic. I just brought this up last week with Quentin Tarantino. You can see that in Fury Road in that both Max and Furiosa do not change. They do not arc. But you’ll also notice that Nux (the “War Kid” who originally would do anything for Immortan Joe) ultimately relinquishes his allegiance to him to help the rebel crew. Audiences like at least one character in a movie to go through some level of change. If you’re worried about a character flaw that would feel dumb or false for your heroes, know that you can use other characters in your movie to explore an arc as well.

Bonus Tip! – A great climactic set piece is all about making it look like there’s no way your heroes will win – It should never EVER feel like your heroes are doing well in a climax. You want the opposite to happen. Keep stacking the odds against them. Fury Road is a great example of this. When the protagonists are forced to go back through the bad guys to get away, there isn’t a single moment in that sequence where we think our heroes have a leg up on the bad guys. There are an endless amount of cars. As soon as one is taken out, another one takes its place. The bad guys are able to snag one of the girls. Max, on top of the truck, is barely holding off bad guy after bad guy. We feel positive that our heroes will fail. Which is exactly how you want it to be.

Dude, what are you doing!? You’re sending your script out without getting professional feedback first? You’re NOT getting help from someone who can tell you EXACTLY what’s missing and how to fix it? Why?? You only get one shot with these industry contacts. Don’t screw it up by sending them the 10,000th average screenplay they’ve read this year! I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested. Use code phrase ‘WARM IN JULY’ and I’ll take a hundred bucks off a pilot or feature consultation. Chat soon!

Genre: Comedy I guess?

Premise: (this logline is from IMDB) THE CURSE is a genre-bending scripted comedy that explores how an alleged curse disturbs the relationship of a newly married couple as they try to conceive a child while co-starring on their problematic new HGTV show

About: Today’s pilot script comes from Benny Safdie and Nathan Fielder. Benny is obviously one half of the directing team behind Uncut Gems. Fielder had a show called Nathan For You. Somehow, these two kidnapped Emma Stone to be on this show, which will come out on Showtime.

Writers: Benny Safdie & Nathan Fielder

Details: 41 pages

I’m a HUMONGOUS fan of the Safdie Bros work ever since I was dragged, kicking and screaming, to a special screening of Good Time. My date kept insisting, “They’re supposed to be the next big thing in directing.” I rolled my eyes. “You know how many times I’ve heard someone anointed as the next big thing in directing?”

Flash-forward three hours and I felt like I’d just had a religious experience. Wow was that movie good. But what happens when two Safdies become… one Safdie? Does this show still have a chance? Since I’m writing this paragraph after I’ve read the pilot, I can tell you that it definitely does not.

36 year old Asher is a hipster type who’s married to 35 year old Whitney. What do these two do? Since I’ve written several drafts trying to summarize the plot and failed, I’ll let the script explain it to you. Here, Asher and Whitney, who flip houses, are being interviewed by a local newsperson about their job. Here’s how that interaction goes….

Yes, Asher and Whitney have a reality show where they flip houses and partner with companies to bring high-end stores into low-income neighborhoods and then give a small portion of the jobs from those stores to local people, which they then document for their TV show.

Right. Great stuff.

Anyway, I get the feeling that Asher and his co-worker, Dougie, are supposed to be like Dumb and Dumber, maybe? For example, Whitney sends them out to get some B-roll and encourages them to film stuff that makes them look good. So Dougie films a shot of Asher giving a homeless woman $100.

Once they get the shot, Asher runs back to the homeless woman and confides in her that he accidentally gave her $100 when he meant to only give her $20. So he asks for the $100 back. And, after he takes it back, she yells at him that she’s put a curse on him. That’s right folks. As if we didn’t already have enough going in this show, they have decided to now add a curse storyline.

And that’s the setup for The Curse.

Yesterday, I reviewed a script that everybody should read in order to become a better screenwriter.

Today, I’m reviewing a pilot that everybody should also read to become a better screenwriter.

There’s one difference.

Read yesterday’s script to see WHAT TO DO. Read today’s script to see WHAT NOT TO DO. And when I say, “not to do,” I mean “NOT TO DO!!!!!” I don’t think there’s a single good creative choice that was made in this pilot. It’s really really REALLY bad. Bordering on Mattson Tomlin bad. Bordering on ‘they’re going to be embarrassed when they put this on the air and people see it’ bad.

Whenever people aren’t vibing with your script, it can usually be traced back to the concept. If the concept is weak or messy or boring or stupid, you’re building everything that follows – your characters, your plot, your dialogue – on a shaky foundation. So it doesn’t matter whether your plot or your dialogue works. We’ve already decided the show sucks.

I would put The Curse up there as one of the most misguided show ideas I’ve ever come across. Bear with me for a second as I explain this show to you. It’s about a group of people who flip houses and who also build upscale stores in low-income neighborhoods and who also have a reality show that follows them around while doing this and who also have one of their production team members get cursed by a witch.

Marinate on that for a second.

Just throwing out thoughts right now.

But did it ever occur to anyone who was a part of this project that, oh, I don’t know, there’s like 1500 too many things going on in this show?!?

For crying out loud PICK ONE THING. Talk about confusing. I didn’t even know it was possible to come up with a show this confusing.

Was Emma Stone conned into this? Did she read this script? Did anybody pitch it to her? Cause the only thing that makes sense is that she was friends with either Nathan Fielder or Benny Safdie and joined the show cause they asked. Because I would bet my life that there is NO WAY any actress who read this part, much less one with as many choices as Emma Stone, would sign onto this.

I might be okay with all this plot noise if the show was funny. But there are so many confusing ideas clashing with each other here that you’re not even sure what genre of comedy you’re watching. Is it lowbrow comedy, satire, broad comedy? Feels to me like mish-mash random desperateness comedy. During one two-minute period, we see two men’s penises. One, a close up while going to the bathroom. Another, when an older gentleman purposely has his penis hanging out of his pants. I’m guessing this passes for comedy somewhere. But you’d be hard-pressed to tell me where.

The NUMBER ONE SCREENWRITING MISTAKE I SEE is writers OVERCOMPLICATING THEIR STORY. Period. That’s it. That’s the biggest recurring mistake I see, and I see it, literally, a dozen times a month. And writers never learn. They think more equals better.

That’s not the case with screenwriting. More equals messier. More equals clumsier. More equals more confusinger. There’s so much shit going on in this story, it never had a chance.

I don’t see why I have to write anything else. There are no more lessons to learn here.

Listen to me if you want success in your screenwriting career: STOP OVERCOMPLICATING YOUR STORIES. Pick a clean easy to understand idea, then populate it with some kick-ass characters. That’s it. That’s the formula for TV.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This was my biggest fear when we moved from a 100 TV Show industry to a 700 TV show industry. Is that the writing talent would get so watered down, we’d have to wade through 50 terrible TV shows just to find one good one. The Curse should rename itself to The Worst. Cause it may be the worst of those 700 shows.

Today I review a script by the writer of the NUMBER 1 screenplay on my Top 25 List, E. Nicholas Mariani!

Genre: Drama/True Story

Premise: A black lawyer attempts to free 87 black men who were erroneously charged with killing a white man in 1919 Arkansas during the height of the Jim Crow era.

About: E. Nicholas Mariani needs no introduction on this site. He is the author of the number one script on my Top 25. Somehow, 41 other scripts scored higher than this one on the 2018 Black List. Injustices all over the place!

Writer: E. Nicholas Mariani

Details: 180 pages!

You know, if there’s one thing I like about Nicholas Mariani, it’s that he doesn’t swing for doubles. He swings for grand slams. He goes ALL IN with The Defender. And when you go all in, you either fall on your face in spectacular fashion, or you win an Oscar. Let’s see where The Defender’s going to end up.

It’s Little Rock Arkansas, 1919. World War 1 has just ended. It’s a celebratory day in town. Except for 55 year old black attorney Scipio (pronounced ‘Sippy-oh’) Africanus Jones, who’s just watched yet another black man he’s defended, a soldier no less, hanged.

Scipio is an interesting person. He was born a slave. He worked the cotton fields. He then clerked at a law office where he became a self-taught lawyer. He’s since become very well-respected by people of all colors in town.

But that respect is about to be tested. A young black man named Robert Hill comes to Scipio’s office and asks him to help him form a union in downstate Elaine, a town with lots of black people working the cotton fields. Scipio tells him he’s nuts. The second they find out that black people are forming a union, they’ll come after him. But Robert says he’s doing it anyway.

A few days later, Scipio gets the news that black people down in Elaine who were planning to take over the town killed a white man. In the process, all 87 of the men who were conspiring to do this are in jail. Against his better judgement, Scipio goes down to Elaine, where he finds out that nothing about the stories in the paper were true.

A group of white people attacked the church where the black people were planning the union and accidentally shot one of their own in the back of the head. This created a frenzy and all the white people in town went to hunt down black people. Somewhere between 300-1000 black people were killed.

Scipio realizes that the odds are against him for saving these 87 men, 12 of whom refuse to enter a guilty verdict, meaning that they will all be hanged. But Scipio is one of the most clever lawyers you’ll ever meet so he concocts a multi-leveled plan that will invoke laws that pre-date the American legal system, all in the hopes of winning a case that, if he succeeds, will change America forever.

I had little doubt I was going to like this one.

Mariani is the real deal. How he’s not pulling in million dollar rewrites on Oscar-hopeful projects is beyond me.

My only real criticism of the script is that it’s too long. But Mariani is one of those rare writers whose scripts are so easy to read (even when they’re dealing with serious subject matter) that the script doesn’t feel nearly as long as it is.

Let’s start at the beginning and move our way through the script.

As I’ve told you a million times, how a script begins tells the reader everything he needs to know about if the writer has the goods. If you start with something boring, the reader expects a boring script. If you start with something clumsy and unclear, the reader expects a messy script. If you start with something cliche, the reader expects a cliche script.

There’s an early scene here where a black man is being marched to his hanging in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1919. Tell me how you imagine this scene. Would there be a large group of white people screaming the n-word at the black man as he’s marched to a tree? Would there be an evil sheriff with a wide grin on his face as he eagerly anticipates the man’s death? Would the sheriff then give a speech to the crowd of people about how “this is what happens” when you “disobey the law” complete with a drawn-out southern accent?

I’m guessing 90% of you imagined that scene.

Which is the number one sign that you shouldn’t write that scene. Good writers avoid expectation and cliche. If they feel like they’ve seen it, they’re going to look for another way to write it.

In Defender, the scene takes place right there in the prison yard. The white warden is not happy that he has to lead this man to his death. There is no crowd cheering. The moment is sullen. Regardless of skin color, nobody is comfortable with what’s happening. And when the death is imperfect and the victim suffers, everyone is mortified. Nobody feels good about it.

This scene let me know I was in good hands. I knew the writer wasn’t going to execute scene after scene in the cliche most predictable fashion possible.

Next up we’ve got our main character, 55 year old Scipio Africanus Jones. This character is so damn likable, which is a big reason why this script works so well. A lot of producers and executive types toil over how to make characters likable, as if there’s a secret handbook that keeps all these tricks hidden from the world. But, in reality, you just have to think of what makes a regular person likable. Scipio sticks up for the little guy. Scipio watches, sadly, as a friend hangs, powerless to do anything about it. Scipio is friendly to everyone. Scipio is intelligent. Scipio stands up for himself. There’s no magic formula here. Just imagine what makes you like people in the real world and apply it to your character.

Mariani is also a great scene-writer. Good scene-writing DOES have its own secret playbook and the only way to access it is to write a lot and figure out what works and what doesn’t. Mariani’s scene-writing book seems to be quite large. There’s an early scene that occurs in Elaine where Scipio heads to the courthouse to make some requests from the judge.

This is a pretty standard setup for a scene – two people talking in a room. So to make it more exciting, Mariani adds a scene agitator (you can learn about scene agitators in my book) where the entire town has just gotten back from the funeral of the white man who was killed. So they storm the courthouse, screaming and yelling, seemingly on the brink of breaking in. That basic “two people talking in a room” scene all of a sudden becomes a lot more charged.

I feel like I’m going over the advanced screenwriter’s playbook here, there are so many impressive things Mariani does, but what can I say? He’s a great writer. For example, he could’ve easily had Scipio head to Elaine based off of newspaper headlines alone. Most writers would’ve done it this way. But Mariani knew that it would be better if both Scipio and the audience had a personal connection to the massacre.

So he writes a scene beforehand where Robert Hill comes to his office and tells him about the union he wants to form down in Elaine. We like Robert immediately because he’s fighting for the disenfranchised and because he’s brave. This way, when the news of Elaine hits the papers, both us and Scipio have a vested interest in going down there. It’s choices like this that turn good scripts into great scripts.

Another advanced choice Mariani made was that not every white person who stood in Scipio’s way was bad. In some cases, these men wanted Scipio to win. But they also had their own interests to protect, which led to a lot of difficult choices for both sides. This is where you can really create a powerful story – when you make things difficult for your characters.

Scipio’s most powerful ally is Governor McRae. McRae is motivated by reelection. He wants to make sure that he doesn’t seem too sympathetic to the black populace of Little Rock, which is why he’s leaning towards convicting these 87 men. Normally, you’d think, “well f*$# him.” The problem is that Governor McRae’s opposition is a full-on racist. So Scipio has to play things very delicately. He needs McRae on his side. But McRae can’t be too on his side because then McRae might lose the election, which means Scipio’s town will now be ruled by a man who supports the Ku Klux Klan.

I loved this because it made you think. There was some real strategy involved in every choice Scipio had to make. By far the biggest issue I run into with scripts that deal with race is that they’re too black and white. There’s no subtlety anywhere in the story. Those are the easiest scripts for me to put down.

I don’t know what’s up with me this week because yesterday I was tearing up during Black Widow. Then during this script I was practically bawling by the end. But man, this was a really good script. If you’ve got the time and you want to become a better screenwriter, read this script. This is what top-level screenwriting looks like.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Nothing should ever be given to your characters for free. A representative from the NAACP shows up offering money and positive press coverage to Scipio. But if they give it to him, they want to be the face of the trial. They want all the glory if they win.

Genre: Superhero

Premise: While the Avengers are on a break, Black Widow receives a message from her long lost sister that a Russian villain is planning something gnarly, requiring her to re-join her family to take care of the problem.

About: Black Widow’s 80 million dollar weekend haul proves that the only thing that Covid can’t beat… is Marvel. Eric Pearson wrote the script. And while that normally wouldn’t be a story, IMDB Pro has added a new classification – SCRIPT DOCTOR – to its credit vocabulary, and it appears that Pearson has script doctored almost every Marvel movie since 2015’s Ant-Man. What “script doctoring” means here is anyone’s guess! Black Widow was directed by Cate Shortland, who was heavily recruited by Scarlett Johansson. Johansson was big on Shortland after seeing her 2012 film, “Lore,” about five children forced on a journey during the last days of World War 2. Johansson called the film, “About as perfect of a movie as there is.” Rotten Tomatoes seems to agree with her, giving the movie a 94%. Although average moviegoers weren’t as excited, assigning the film a 76%.

Writer: Eric Pearson (story be Jac Shaeffer and Ned Benson)

Details: 133 min

I have a serious question.

Is Black Widow a superhero?

At one point, her sister says, ‘I called you because you’re the only superhero I know.’ I was like, “Sweetheart, can you do a cartwheel? Then you’re just as much of a superhero as Black Widow is.”

To this day, I still don’t know what Black Widow brings to the Avengers besides her flippy leg-chokehold bodyslam move. Can’t Tony Stark build her a suit to give her super strength or something? He basically turned the spidey-suit into a mini-Iron Man suit.

According to the latest Avengers movie, Black Widow is dead. Which means this Marvel incarnation takes place in the past, between Avengers assignments. Black Widow (aka Natasha) receives some red serum in the mail from her long lost sister, who implores her to use Tony Stark to find out what the serum is.

Instead, Natasha heads to Budapest to ask her sister, Yelena, why she sent it to her. The two haven’t seen each other since they were Russian children in a fake US family on assignment in Ohio. They don’t seem to like each other. I gathered that since, instead of hugging, Yelena tries to decapitate Natasha with a steak knife. The serum, as it turns out, allows people to be controlled by a mysterious man, who is using it to build an army of living drone soldiers.

The two realize they won’t be able to take this guy down alone so they go break their “father,” Alexei, out of prison and recover their “mother” as well. Before the family can take down the big baddie, they’ll first have to defeat Taskmaster, some metallic dude who has a Captain America shield. Will this pretend family be able to pull themselves together in time to get the job done? Or will they do what they always do – implode?

The funniest thing about Black Widow is that they’ve been campaigning to get Scarlett Johansson her own movie for almost a decade now and when they finally do it, she’s not even the star! Her sister, Yelena, is the star. She’s the one who has the problem. Natasha’s just along for the ride. As proof of how pedestrian a character Black Widow’s been, Yelena outshines her in every scene they’re in.

There’s a positive spin to this, though. A smart person who worked at Marvel said, “If we make a movie with just Black Widow, we’re f#$%d.” They knew she was too boring (and not superhero’ish enough) to carry a movie. So they built this team around her. And thank God they did because doing so turned Black Widow into a pretty darned good movie.

I actually learned something really valuable while watching this film.

When in comes to action movies, so many writers focus on the premise and the plot and set pieces and cool scenes. And all of those things are, of course, important. But let’s be real. If you’ve seen any big-budget movie in the last five years, you’ve seen this movie. You’re not going to come up with a set piece we haven’t seen before. You’re not going to come up with a car chase we haven’t seen before. You’re not going to come up with a fight scene that’s going to blow us away.

No matter how insane your imagination is, it’s unlikely you will ever come up with something that we haven’t seen before in other movies.

Which leads us to an obvious follow-up question: “Then what’s the point?”

Why even try?

If all we’re doing is copying things we’ve already seen, then why create yet another bloated CGI summer movie?

This movie reminded me why.

Because the truth about ANY movie is that if we connect with the characters, all of those moments – the car chases, the fight scenes, the set-pieces – we care about them. Even though we know they’re fake. Even though we’ve seen them before. When you connect with the characters, you enter into a quasi state of belief where the fictional world becomes reality.

Therefore, when you’re writing these movies, your core focus should be on creating a) believable characters and b) believable relationships. If you can tap into that rare thing where the character actions and interactions feel authentic – feel like they could exist in the real world – we will connect with and care about those people.

This script did a tremendous job of exploring a dysfunctional family. This was basically Little Miss Sunshine, the superhero version. This family has deep DEEP SET issues, deeper than any superhero movie I’ve ever seen. First off, the four family members? They’re not even a real family. They were a fake Russian family that was cobbled together to look like an American family for a covert operation in Ohio. So they grew up like a family, but they were all strangers to each other. That alone makes for a really interesting setup.

When you’re a pretend family, how much are you supposed to care about the others? When the mission of “Pretend Family” is over, how much responsibility do you have to talk to these people again? That conflict of not technically being a family yet still feeling the same guilt and frustrations associated with being a family made for some extremely emotional moments. I teared up more in this movie than any Marvel movie.

One of my worries going into this was, “How are they going to explain that Black Widow ghosted her family for twenty years?” But once you watch the movie, you get it. They’re not really a family. They don’t owe each other anything. And that makes Natasha and Yelena’s and Alexei’s interactions all the more fascinating since they’re all skirting the line of “I don’t have to care about you but I also want to care about you.”

I always find dialogue interesting when the motivations behind it are complex. And the motivation behind every dialogue scene in this movie is complex. Seconds after Yelena and Natasha rescue Alexei from prison, Alexei wants to talk about what his next mission is going to be while the girls are dealing with the fact that the only father figure they’ve ever had hasn’t even acknowledged that he’s happy to see them.

When he’s confronted with this, he makes an inquiry into how they’re doing, which quickly devolves into Yelena chastising him for placing her in a Russian spy training program where her uterus was ripped out to ensure that she would never have children. You got the sense that any conversation between this family could devolve quickly into that territory, which created that “walking on eggshells” undertone that makes dialogue so much more lively.

Black Widow works because the family works. Too many amateur screenwriters approach their big action movies the opposite way. They cook up a concept. They craft a plot. And then they try and cram their character storylines into that plot. I’m not saying that’s never worked before. But if you want to write an action movie where the viewer is actually engaged, Black Widow is the way to do it. Get the character right. Get the family dynamic right. And everything else in the story should follow.

Marvel continues to be the benchmark for high-budget franchise filmmaking. And, right now, the competition isn’t close.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Normally, I encourage screenwriters to avoid bringing their hero’s past into the movie. Movies work best in the present. Especially action movies, which are all about the here and the now. However, when it comes to any movie dealing with family, IT’S ALWAYS ABOUT THE PAST. It would be weird if you made a family movie that DIDN’T bring up the past. Black Widow is all about the past. It’s about the fake lives they grew up leading, the terrible torture their father sent them into as children, the choices by Yelena and Natasha to avoid each other as adults. Everything in this movie is about overcoming the past. And, with movies about family, that’s how it should be.

Updated Marvel Universe Rankings

1) Thor Ragnorak

2) Captain America: Winter Soldier

3) Avengers: Infinity War

4) Captain America: Civil War

5) Spiderman: Homecoming

6) Guardians of the Galaxy

7) Ant-Man

8) Iron Man

9) Black Widow

10) Black Panther

11) Avengers: Endgame

12) Doctor Strange

13) Spiderman: Far From Home

14) Captain Marvel

15) Captan America

16) Thor

17) Guardians of the Galaxy 2

18) Iron Man 2

19) Iron Man 3

20) Loki

21) The Incredible Hulk

22) Avengers: Age of Ultron

23) Falcon and Winter Soldier

24) Wandavision

25) Thor: The Dark World

26) Ant-Man and the Wasp

Sci-Fi Showdown is just two months away! So keep working on those entries. Here’s information on how you can enter the showdown. It’s totally free!

As we continue to march towards Sci-Fi Showdown, I thought I’d do some research on which sci-fi movies have been successful over the past five years (including a 2 year pandemic buffer). Specifically, I was looking for ORIGINAL ideas since those are the ones any writer can write. Coming up with the list was a LOT HARDER than I thought it would be.

I didn’t want sci-fi movies that were heavily mixed with other genres. So I discounted sci-fi comedies (Thunder Force!) and horror masquerading as sci-fi (A Quiet Place, 10 Cloverfield Lane). The definition of “original” had to be flexible because there were many cases where an idea was based on something else even though it was basically original. For example, if a movie was based on a short story that it barely resembled and the screenplay was written on spec, I considered that an original idea for the list. Likewise, if a script was based on a graphic novel that sold 10 copies and was also written on spec? That’s an original idea to me. Original ideas by giant directors who can get any movie made didn’t count (so no Chris Nolan films). The idea with this list was to highlight the types of concepts that, because they weren’t based on any IP, could’ve theoretically been written by any old writer, including you.

As I combed through the past several years, one of the most surprising things I found was that while the top of the box office was flush with big juicy sci-fi offerings, original sci-fi films were harder to locate. For those, I’d have to descend way down in the box office rankings – we’re talking 50s, 60s, 70s. There was such a striking financial difference between IP-backed sci-fi and original sci-fi that I was convinced I must’ve missed a bunch of films. So I went back through every year a second time and confirmed, sadly, that NOPE, this was it. Now, in the spirit of fairness, more sci-fi films are being made for streamers. So this list isn’t perfect. For example, had The Tomorrow War launched in theaters, it would’ve made this list. The Mitchells vs. the Machines would’ve technically made the list, but I consider animation separate from live-action sci-fi. For the most part, this is an accurate representation of what original science-fiction looks like at the box office. Let’s take a look…

Title: Edge of Tomorrow

Writers: Christopher McQuarrie, Jez Butterworth, John-Henry Butterworth, graphic novel by Hiroshi Sakurazaka

Logline: A soldier must relive the same day over and over again in order to save mankind from an invading alien army.

Domestic take: 100 mil

Worldwide take: 370 mil

Title: Passengers

Writer: Jon Spaihts

Logline: A passenger who erroneously awakes 90 years early on a colony ship to another planet decides to open up the cryo-bay of a woman in order to keep him company, even though he knows he will ruin her life by doing so.

Domestic take: 100 mil

Worldwide take: 300 mil

Title: Tomorrowland

Writer: Damon Lindelof, Brad Bird, Jeff Jensen

Logline: A teenage girl bursting with scientific curiosity and a former boy-genius inventor embark on a mission to unearth the secrets of a place hidden between time and space.

Domestic take: 93 mil

Worldwide take: 209 mil

Title: Arrival

Writer: Eric Heisserer (short story by Ted Chiang)

Logline: A linguist is called in by the U.S. military to figure out how to communicate with an alien species who has just landed a dozen spacecraft around the world.

Domestic take: 100 mil

Worldwide take: 203 mil

Title: Gemini Man

Writer: David Benioff, Billy Ray, Darren Lemke

Logline: An over-the-hill hitman faces off against a younger clone of himself.

Domestic take: 50 mil

Worldwide take: 173 mil

Title: Ad Astra

Writer: James Gray, Ethan Gross

Logline: An astronaut undertakes a mission across our solar system to uncover the truth about his missing father.

Domestic take: 50 mil

Worldwide take: 127 mil

Title: Life

Writer: Rhett Reese, Paul Wernick

Logline: A team of scientists aboard the International Space Station discover a rapidly evolving life form that threatens all life on Earth.

Domestic take: 30 mil

Worldwide take: 100 mil

Title: Underwater

Writer: Brian Duffield, Adam Cozad

Logline: A crew of oceanic researchers working for a deep sea drilling company try to get to safety after a mysterious earthquake devastates their deepwater research and drilling facility located at the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Domestic take: 17 mil

Worldwide take: 40 mil

Title: Ex Machina

Writer: Alex Garland

Logline: A young programmer is selected to participate in a ground-breaking experiment in synthetic intelligence by evaluating the human qualities of a highly advanced humanoid A.I.

Domestic take: 25 mil

Worldwide take: 36 mil

Title: Upgrade

Writer: Leigh Whannell

Logline: Set in the near-future, a technophobe who becomes crippled after an accident is forced to try a new experimental computer chip that will help him walk again.

Domestic take: 11 mil

Worldwide take: 16 mil

I’m not going to lie. Doing this research was discouraging. Who knew breaking through with an original science-fiction idea was so difficult!? I expected to find so many more films for this list. But it wasn’t just the lack of films. Several of these entries were considered failures! So even the sci-fi successes are failures.

I think the big question I came away wondering was, why is there such a huge gap in interest between intellectual property science fiction and original science fiction? Cause it’s not a small gap. It’s not even a medium gap. We’re talking IP movies that make 500 mil and then you have to travel waaaaaay down the list to find an original idea that makes 40 mil. I suppose you could go with the obvious answers. We gravitate towards movie universes we’re familiar with. You’ve also got the deep pockets argument. Franchises that have more money can add more spectacle. And people love spectacle in their sci-fi.

But if you dig a little deeper, I think the real problem is that audiences don’t find “straight science fiction” appealing. They usually want some comedy with it (Back to the Future!), some horror with it (A Quiet Place!), or some action with it (Ready Player One). A movie like Ex Machina sure gets sci-fi nerds like me excited. But it doesn’t get the average moviegoer excited. For that reason, your “straight sci-fi” concept has to be INSANELY good in order to get noticed. It’s gotta be “Gemini Man” good (bad movie but kick-ass concept) – something cool and exciting that gets people revved up when they hear it. Because when you’re going up against franchise sci-fi IP, you need ammo in your chamber. And your concept is your only ammo.

Another thing I realized was how important writing a compelling main character is. I know I tell you to do this no matter what kind of script you’re writing but here it’s even more important and let me explain why. I want you to check out the domestic takes versus the worldwide takes for Ad Astra, Gemini Man, and Life (you can include Passengers and Edge of Tomorrow if you want as well). All three of those movies underperformed at the US box office. But their worldwide box office was over three times what they made domestically.

That’s because those movies starred Brad Pitt, Will Smith, and Ryan Reynolds, all big earners on the international stage. Now look at the box office bumps for Underwater, Ex Machina and Arrival. The multiples are much smaller. That’s because they didn’t have a box office star that appealed to international audiences.

This tells me that one of the keys to getting original sci-fi movies made is to come up with a character that entices a big actor. Cause if you can get a big actor, financiers are more willing to finance your film since they know, at the very least, they’re going to get their money back internationally.

I pointed out, when I originally reviewed the Ad Astra script, that the main character was autistic. No doubt that’s why Pitt signed on to play him. Gemini Man allowed whoever came on to that role to not only play one part, but two! What actor isn’t going to want to also play a 30 year younger version of himself? Edge of Tomorrow is a huge acting challenge in that you’re playing a character who’s dealing with the insanity of having to get slaughtered every single day of his life.

Granted, you can overthink this stuff. Why did Chris Pratt sign on to Passengers, a character that didn’t have a whole lot to do other than keep a secret from another character. I don’t think we’ll ever have an answer to that. When it comes to his newest film, The Tomorrow War, Pratt’s decision had nothing to do with the character and more likely revolved around his support for the military.

So, yes, you can factor that in as well. Every actor has things that they love. If you know what those things are, write a sci-fi movie that leans into them. Regardless of that, it only improves your chances when you write a strong memorable lead character. Sci-fi writers get so wrapped up in their concepts that they often overlook their main character who, as a result, ends up being boring. The Matrix is a really cool idea. But let’s not forget Neo is an even bigger star than that concept. That’s why that movie shined so bright.

Another thing you’ll notice from this list is that “monster in a box” situations work really well with sci-fi. Underwater is monster in a box. Ex Machina is monster in a box. Life is monster in a box. It’s one of the most time-tested setups for a movie and seems to fit science-fiction like a nice snug pair of isotoners.

Finally, I don’t see a bad idea in this bunch (Tomorrowland maybe?). All of these ideas are interesting. Even Passengers, with its offbeat narrative, is thinking man’s science fiction. Arrival definitely makes you think. Edge of Tomorrow has your brain twisted in knots trying to figure out how you would handle the situation. Life and Underwater are lighter in the intellect department. But everything else reminds me of the importance of using science-fiction to provoke thought.

My final conclusion after today is, why buy one lottery ticket when you can buy two? Of course, focus on coming up with a great science-fiction concept first. Something clever. Something fresh (a new spin on an old idea). BUT where you’re really going to separate yourself from everyone else is by also creating an interesting main character. If your hero’s just some average Joe, someone Bruce Willis could play in his sleep, that’s not good enough. Preferably, your hero will be just as interesting as your concept. You kind of have to put yourself in the shoes of an actor and ask, “Would I kill to play this part?” If you can’t imagine actors getting excited to play your main character, go back to the drawing board. Why buy one lottery ticket when you can buy two and double your chances of winning?

Hey Scriptshadow reader. You tired of sending scripts out there and not getting any response? Wondering what’s wrong? Or, more importantly, how to fix it? Send your script to the guy who’s read everything – who knows exactly what the industry is looking for. I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested. Use code phrase ‘WARM IN JULY’ and I’ll take a hundred bucks off a pilot or feature consultation. Chat soon!