Genre: Action

Premise: Following in his murdered mother’s footsteps, Michael Griffiths enlists in the United States Postal Service… only to discover a mail route full of surprises and a job that means maybe, just maybe, saving the world.

About: This script finished with 11 votes on last year’s Black List. This writer is just getting started. He does have some Hollywood experience though, being Nicholas Stoller’s assistant on both Neighbors 2 and Storks. It looks like Amazon Studios may have purchased this to produce. It also appears to be an original spec. It isn’t based on anything that I know of.

Writer: Perry Jane

Details: 122 pages

Before I dive into this one – because I’m going to warn you in advance, it wasn’t for me – I want to say something positive. Which is that it was nice to see a big fun movie on the Black List for once. The Black List has become… I don’t know… weird. Some of the scripts that make the list defy explanation. So it’s cool that something your average moviegoer would pay for got on there.

Unfortunately, for script snobs like me, The U.S.P.S. was more “general postage rate” than “Express Mail.”

When word gets to 20-something security guard Michael that his mother died on her postal route, he’s already feeling guilty about not spending more time with her. But then Michael gets a security box key, and that’s where he learns that his mom was a lot more than your average postal worker. She was an agent who used her postal office cover to take down bad nasty people. His mother didn’t die. She was murdered!

Michael is quickly recruited by someone named Sinda, who knew his mother well. She takes Michael to a secret underground location where he’s instated as a trainee in the U.S.P.S. program – The United States Program of Spies!!!!! (“Neither snow nor rain nor gloom of night, nor threat of suffering and death, stays these agents from the swift completion of their mission.”)

Sinda believes that Michael’s mother was killed by a woman named Bonnie Jo Boone, who has just sent a message to the U.S. government that they have to give back 5 trillion dollars to be dispersed to all the poor people in the country that it was “stolen” from. Bonnie Jo works with six modified humans that are basically like, cyborgs, I guess. Translation: she’s serious.

Michael doesn’t get the gig right away, though. He has to try out against a bunch of other prospective spies. So he has to do things like sneak up to a house and deliver mail without anybody noticing.

When Bonnie Jo accelerates her plan, Sinda realizes they have to do the same. So Michael is promoted to a spy on a ‘probationary period.’ Michael is sent to a suspicious bank in the middle of Manhattan, where he discovers Bonnie and her team, waiting to rob it. The postal spies attack, which sends everyone on a crazy car chase through New York, complete with an old postal truck that transforms into a super-car-weapon-thing.

Bonnie Jo is able to get away. But Sinda learns something even worse. That Bonnie Jo is working with someone from the inside! They have a traitor in their midst! So off they go to the supposed traitor’s party (someone at the FBI) where they look for clues to take him down before Bonnie is able to commence her bank-draining plan that will move 5 trillion dollars out of the hands of the wealthy and into the hands of the people!

What is plot?

Plot is the sequence of events that push your primary story forward.

The spacing between these “plot beats” will dictate whether your script is designated as “plot heavy” or “plot light.” Smaller movies tend to have more spacing between their plot beats. Big Hollywood movies tend to have less. The reason is obvious. People who go to see a big Hollywood movie are expecting to be entertained consistently the whole way through. So you’ll see a lot of plot beats in Fast Furious, Iron Man 3, Star Wars.

Here’s the problem, though. If you erase all spacing between plot beats, your story loses its soul. If the only thing that is happening in your script is you’re racing your characters from one plot marker to the next, it’s hard for the viewer to connect with the characters. And that’s my problem with The U.S.P.S. It’s plot plot plot plot plot plot plot plot and plot.

Now the writer of The U.S.P.S. may argue that he does have some slower moments. We see Michael get drunk one night thinking about his mom’s death. I think there are a couple of more scenes like that throughout the script. Here’s the thing, though. You don’t get points for trying. For character-driven moments to resonate, you, the writer, have to care about them. If you’re just putting them in there because a screenwriting website told you to, or because you want to avoid someone giving you the note that you didn’t focus enough on character, they’re not going to work.

For character stuff to work, you have to be interested in the internal workings of your characters. You have to want to be exploring something with them that you’re just as curious about as your plot. One of the reasons the last two Avengers movies were so popular is because of Thanos. This is a guy who truly believed in what he was doing and had to make some horrible choices, including killing his own daughter, to succeed at his mission. There was something going on in that character. Something he was battling inside.

This is a major difference between the screenplays I read that are good and the ones that are bad. The good screenplays are almost always the ones where the writer is curious about the human condition with at least one of their characters. They want to know what makes a person tick, not how many ticks to the next plot twist. They’re interested in what it feels like to be Wade Wilson (Deadpool), who’s forced to stay away from the love of his life because he’s been burned beyond recognition and is ashamed of how he looks. They don’t care about the flashy Deadpool fight scenes. Well, they do, but they know those won’t work unless they get the character right.

And what’s so hard for writers – especially new writers – to understand, is that you can’t fake it. You can’t show a character looking sad remembering their dead parent if you haven’t sat down and thought about how that death has shaped them as a human being. Because it’s that shaping that’s going to come out in every scene they’re in. If you have to remind an audience that a character is affected by a traumatic event, you probably haven’t figured out who your character is yet. Characters LIVE those events.

Look, this script wasn’t bad. It’s like an American version of Kingsman. So if all you care about is eye entertainment, it might be fun. It’s a little out-there. A bit goofy for my taste. But it should make for an interesting movie.

I guess my issue is that U.S.P.S. felt like a writer who had 52 beats he had to stuff into a 120 page package and his mission, instead of writing something that explored the human condition in an entertaining way, was to make sure all 52 beats got in there through hell or high water. For that reason, the script couldn’t breathe. It was always about getting to the next checkpoint. And that’s why it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I want to talk about bolded underlined sluglines for a second because I see them being used occasionally, including here. One of the goals of a writer should be to make the reading experience as easy as possible. The more your eyes flow from left to right and down the page, the better. Bolded underlined sluglines create the effect of blockages on the page. That big ugly black line feels like something you have to burrow through or go around. If your script is light on locations (and therefore doesn’t have a lot of sluglines), this might not be a big deal. But if you’re switching locations a lot? If you’ve got 3 or 4 on a page? Those bolded sluglines can start to look like giant blockades in the middle of a street. It’s not pleasant. It’s something you should definitely think twice about.

Has Scriptshadow become the “I Care A Lot” channel? Is tomorrow a 5000 word breakdown on Peter Dinklage’s character in the film? No, but the Golden Globes are so weak this year (it feels like the bronze medal game at the Olympics) I don’t have anything to say about them other then they should come up with a new category called, “Most Boring Movie” and just put all the movies in that category because that’s how good these movies look.

On the plus side, this gives me an opportunity to talk about my favorite topic: “I Care A Lot,” a movie I just highlighted a scene from last week. At that point, I had only watched half the movie, mostly because everyone said the movie “fell apart in the second half” and that didn’t exactly motivate me to finish it. But this weekend I sat down and gave it a full watch and you know what?

You were all wrong.

This is a good movie from start to finish and I’m going to explain why. Now, you should know that this is a twisty turny flick and, therefore, you should check it out before you read this because I’m going to be spoiling the bejesus out of everything. But if you’re okay with spoilers, let’s continue.

“I Care A Lot” attempts to walk one of the thinnest tightropes in screenwriting – building the story around an unlikable protagonist. Marla is someone who makes her living off of conning old people. These seniors are perfectly healthy. Yet she thrusts them into assisted loving homes without their permission so she can take control of their finances and rob them blind.

The reason it’s so hard to make scripts like this work should be obvious. If we’re not rooting, in some way, for the main character, nothing else matters. You can have the most amazing plot in the world and it doesn’t matter if we detest the protagonist.

I want to highlight something I’ve never seen any other screenwriting enthusiast talk about. Which is that there are three degrees of unlikable protagonists. I bring this up because a lot of writers push back when you talk about unlikable protagonists and say that as long as they’re “interesting,” you can build a story around them.

But it’s actually more complicated than that because the different degrees of ‘unlikable’ dictate how hard you have to work to get the reader to root for your hero. The first and most common unlikable hero is the ‘bad but not really bad’ protagonist. This would be someone like the Mandalorian. He’s not very nice to anybody. He only does things if it helps him. He doesn’t talk a lot. But let’s be real. He loves Baby Yoda and at the end of most episodes, he’s helped someone else out. Readers will always root for these characters because they know, deep down, they’re good.

The second type of unlikable protagonist is the “genuinely bad” protagonist. This is someone slightly more sinister than the Mandalorian and truly in it for himself. A good comp would be Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson) in As Good as It Gets or Louis Bloom in Nightcrawler. These characters can be downright nasty, saying mean things to people or constantly screwing those people over. Still, if you know what you’re doing as a writer, you can keep us rooting for characters like this.

The third type of unlikable character is the “truly bad” protagonist. What separates this character from the others? These characters are morally bankrupt. Not only do they hurt others, but they hurt people who are lesser than them. Children. Old people. The poor. Underlings. This is what Marla is and this is the single hardest character to make an audience give a shit about.

Which is why so many viewers had a problem with I Care A Lot. We watched this despicable character get away with destroying numerous old peoples’ lives and then, once she’s finally met her match (the son of one of the old people she screws over turns out to be a crime boss), the writer asks us to get behind Marla and root for her in the last 45 minutes.

One of the best tricks you can use when you have an unlikable protagonist is to make the antagonist even worse than they are. That’s the method writer-director J Blakeson used when constructing this movie. He brought in crime boss, Roman, who was even nastier than Marla. Theoretically, at least. Roman tries to kill Marla and her girlfriend, but Marla survives and wants revenge.

Where Blakeson gets in trouble, in my opinion, is that Roman isn’t bad enough to make us Marla’s number one fan. What you have to remember with screenwriting is that how you introduce your character influences the lion’s share of how the audience perceives them. Even though Roman’s a big fat heartless meanie to Marla, we haven’t forgotten how horrible Marla is. How horrible are we talking? Well, I recommended this movie to a friend and she stopped me halfway through the pitch saying, “Oh, that’s horrible,” in response to what Marla was doing to people. She then said she wouldn’t watch the movie.

In other words, your villain has to be EXTREMELY TERRIBLE for the average viewer to change their mind and root for Marla.

While at first I thought Marla and Roman ending up on the same level was a mistake, I began to think that that was Blakeson’s plan all along. This feeds into why the movie works for me. After Marla survives, she kidnaps Roman and brings him to the brink of death, leaving him out in the middle of nowhere, which results in the police finding him, bringing him to the hospital, and labeling him a ‘John Doe.’

We then learn that when a John Doe is found and can’t take care of himself, a legal guardian must be assigned to them. And guess who that legal guardian is? That’s right. Marla. — When movies fall apart, it’s because the writer didn’t come up with a plan. So as they race towards their ending, they throw in a bunch of craziness hoping it’s enough to distract the reader from the fact that they have zero plan. But by creating this twist that pays off Marla’s job, the writer clearly had a plan in mind.

Next up, Marla says she’ll release Roman from her care if he gives her 10 million dollars, which is the amount of money she’s wanted all along. Roman comes up with an alternative idea. Expand her care-taking business. Enough of this small-potatoes shit. Let’s lean into the American dream and go national with this business model of yours. He’ll fund it. She’ll build it. They’ll become partners.

It’s an admittedly zany development. But here’s what I respected. Blakeson understood that neither character should win. They were both too despicable. If she destroys him, we’re upset. If he destroys her, we’re frustrated. The one direction we do not expect the plot to take is a team-up. And the more you think about it, the more sense it makes. They’re both greedy. Of course they want to team up to make even more money than they could separately. It’s the right choice for the story.

What Blakeson also knows is that you can’t have a negative character who doesn’t change over the course of the movie be rewarded. The audience won’t accept it. They need “the right thing” to prevail so they can leave feeling like the world is fair. And so Blakeson has one more payoff. After Marla becomes a multi-millionaire, she’s heading to her car when a crazed man who we recognize from the opening charges at her screaming that his mom died and because of her, he never got to see her, and he shoots Marla dead.

The wicked witch is dead. Order has been restored.

I was told that everything that happens in the last 40 minutes of this movie was random and dumb. But I didn’t see it that way at all. It was all clearly and cleverly constructed with setups and payoffs that make sense. Blakeson knew what he was doing, delivered the movie he intended, and I’m here to tell you he pulled it off. In fact, I would go so far as to say that the reason so many people are so passionate about this film not working is why it works. A movie only truly doesn’t work when our response is apathy. Passion, positive or negative, only comes when a movie affects us in some way. And while this movie made some unconventional choices, the fact that you care a lot about discussing it tells me it worked. :)

Are we getting a black Superman? What’s going on with Kinetic? Are there any updates? What the heck is a “programmer” and why is it now my least favorite word? A trip down memory lane on the eve of David Fincher and Andrew Kevin Walker re-teaming. What is the hardest character for a reader to remember? I review the SINGLE HOTTEST PROJECT IN HOLLYWOOD right now. Did I like it? And what is it like breaking up with Gerard Butler just 14 short days after Valentine’s Day? All of that and more in this month’s newsletter!

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

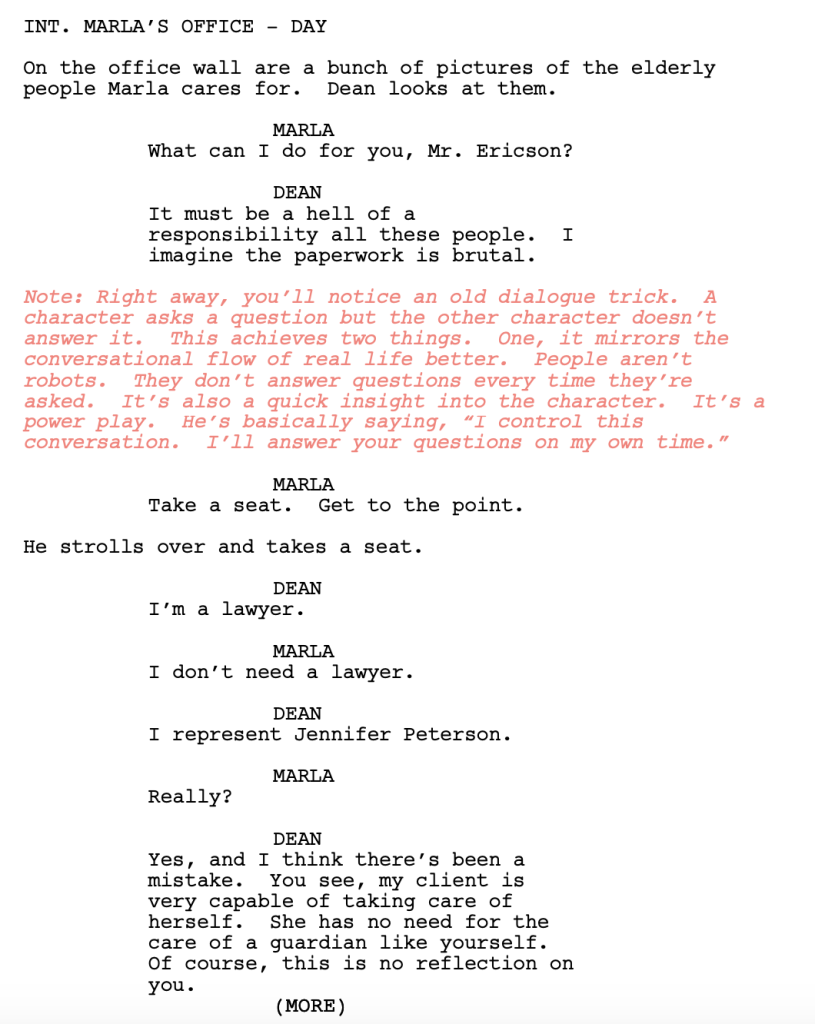

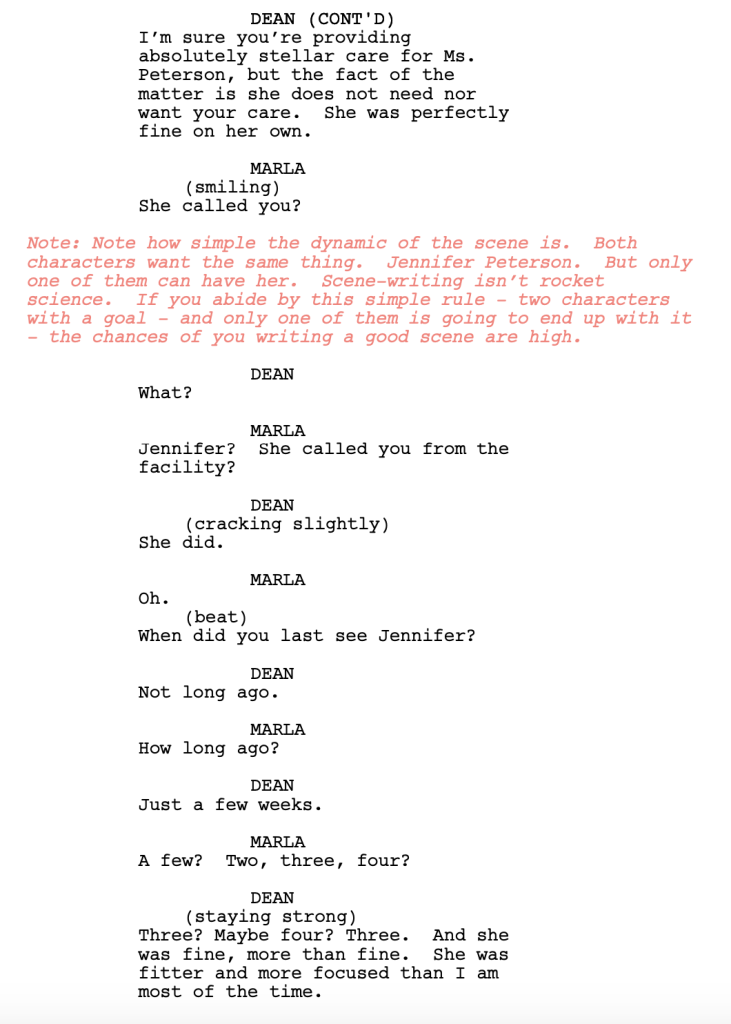

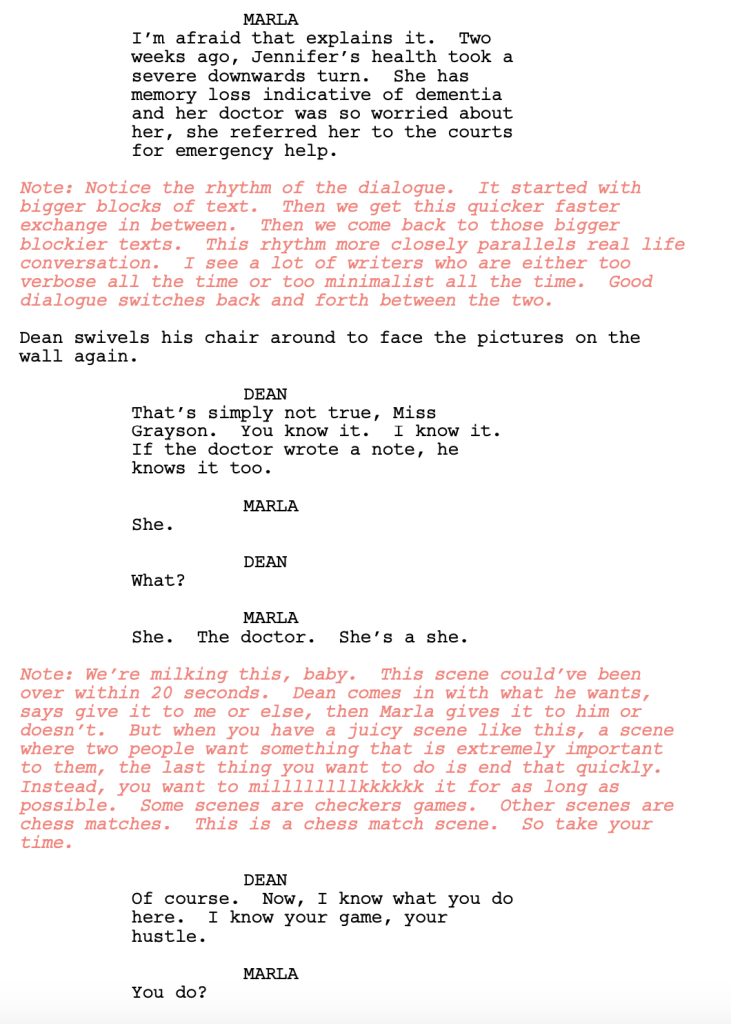

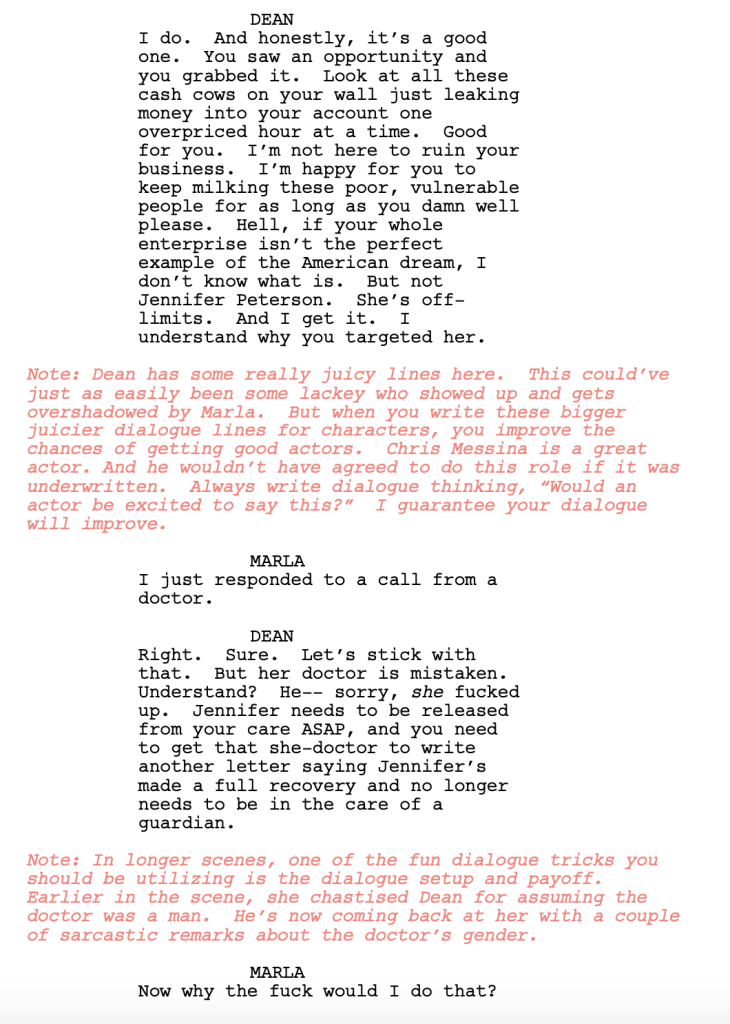

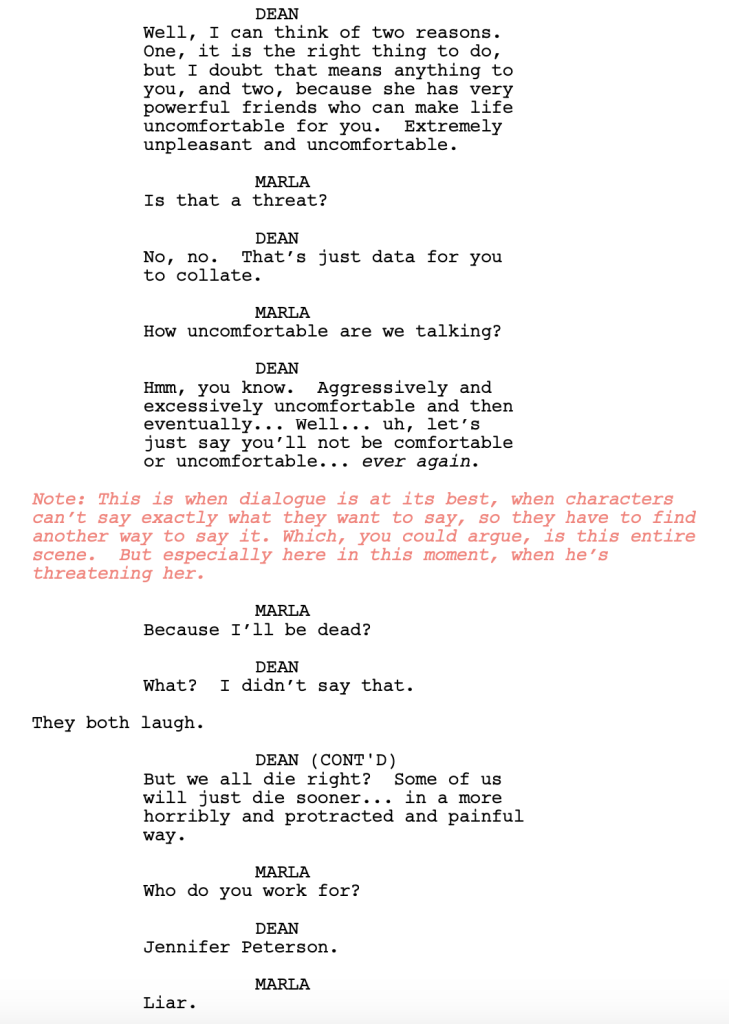

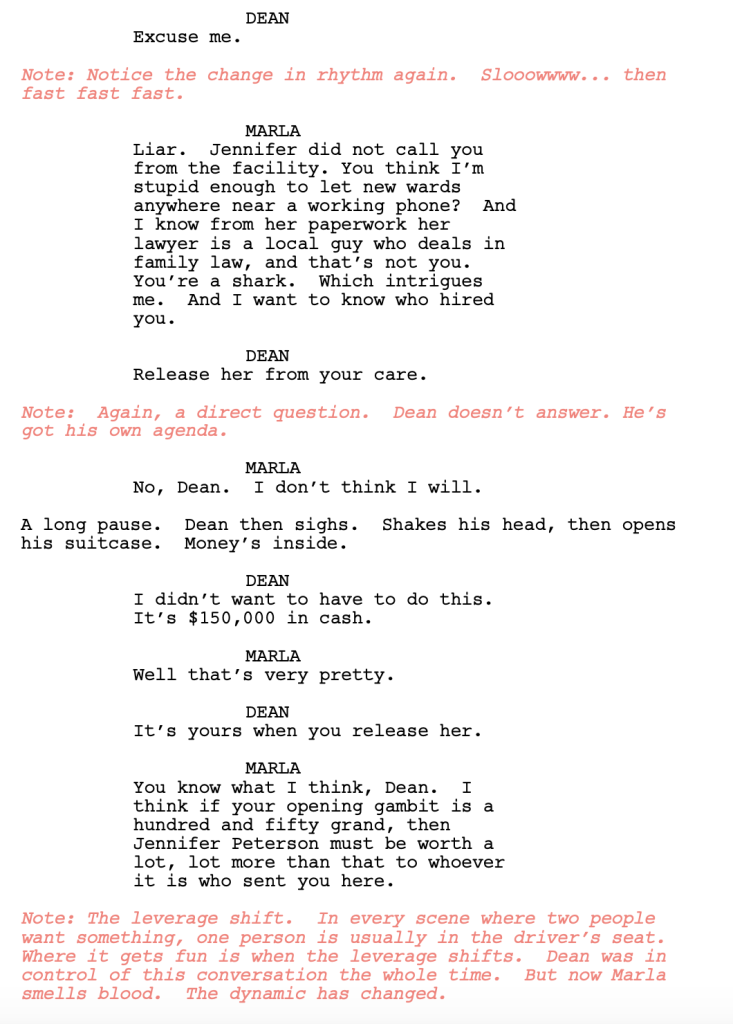

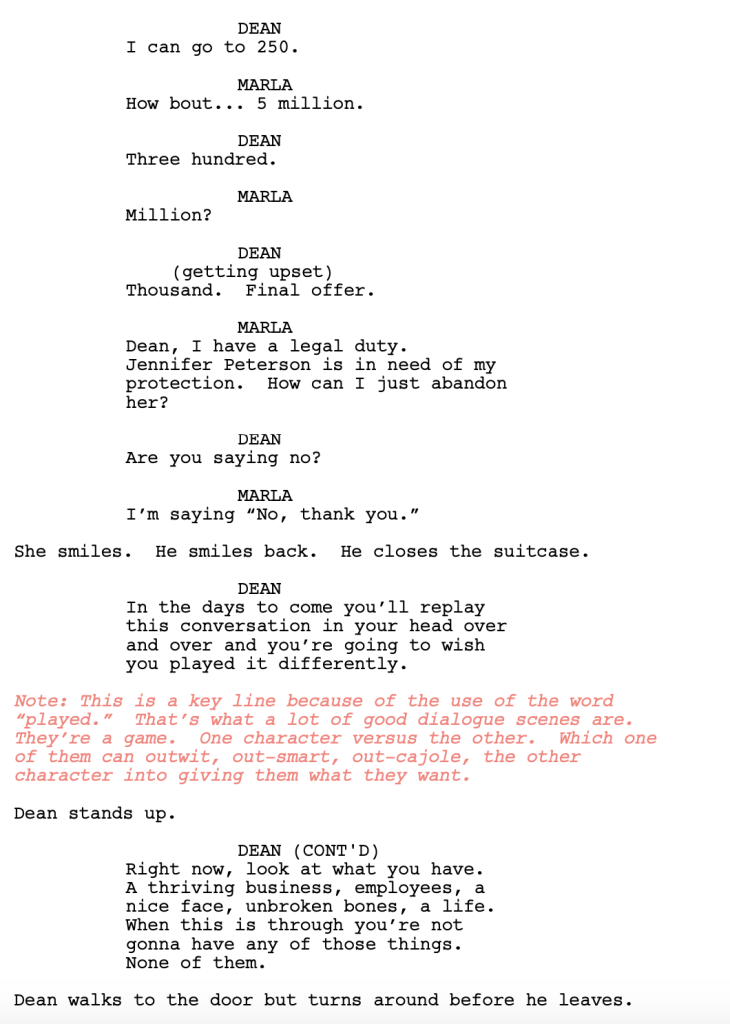

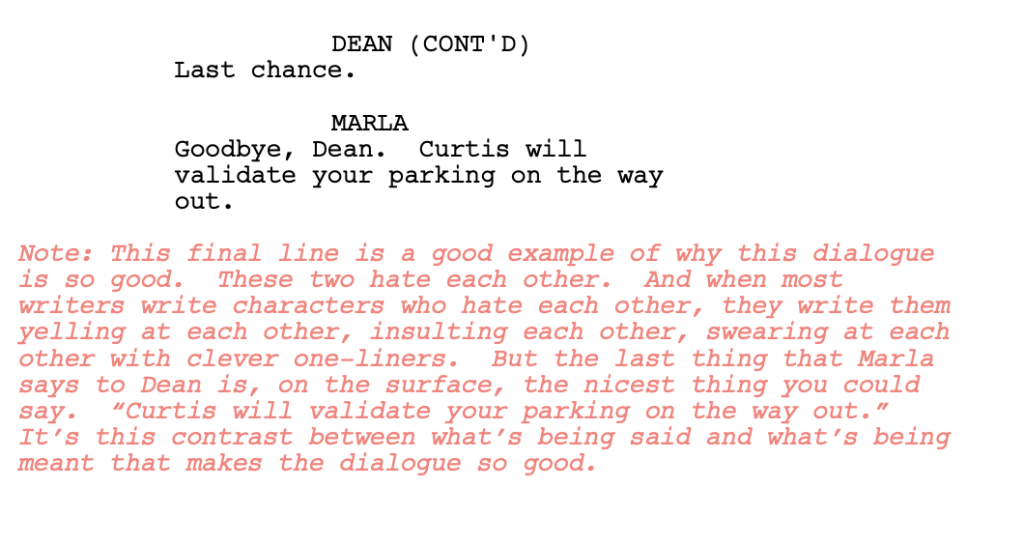

Recently, I started watching “I Care A Lot,” on Netflix. I’m halfway through it and, although I’ve been told that it falls apart, I like it a lot. Specifically, there’s a scene at minute 37 (if you want to queue it up) that I loved. In fact, it’s the best scene I’ve watched all year and has some of the best dialogue I’ve encountered all year. So I thought I’d transcribe the scene for you (this isn’t the official script) and explain why the scene is so good.

Here’s what you need to know. Marla is a professional guardian for older people who can’t take care of themselves. But Marla’s real racket is putting old people in homes who are perfectly fine and then stealing a ton of money from them. Recently, she’s put an older woman, Jennifer Peterson, in one of these homes. What Marla doesn’t know is that Jennifer Peterson’s son is a criminal kingpin. That’s where we pick up the story. A lawyer, Dean, has shown up at Marla’s office and wants to talk.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) A chemical leak in a local water supply in Central Florida wreaks havoc on the invasive population of pythons, leading a family to the fight of their life to survive.

About: This script finished with 11 votes on last year’s Black List. It is the writer’s breakthrough script.

Writer: Creston Whittington

Details: 110 pages

Today was an extremely long and difficult work day for me.

And, after it was all done, I had to read a script. And review it. Starting at midnight.

To say I was in the best mindset to read a script would be an untrue statement. But I bring it up because when you’re on the come-up, your script is likely going to be low priority to whoever’s reading it.

Which means it will probably be read under similar circumstances as to how I read this script – at the end of the day when you’d rather call it a night. Which is yet another reason to put everything you’ve got into your screenplays. Because while you can’t control outside factors such as the mood of the person who’s reading your script, you can control how much effort you put into your script.

Let’s see what we’ve got today.

We start out with some daunting local Florida history:

“Every year, the state of Florida sponsors snake hunts in an effort to exterminate the Burmese Python, an invasive specie introduced to the Everglades by the Exotic Pet Trade.

Although the low detectability of these snakes makes population estimates difficult, most researchers propose that at least 30,000 and upwards of 300,000 pythons likely occupy southern Florida and that this population will only continue to grow.”

20-something Sharon Esperanza has just got off of work (at the local aquarium) and realizes that her 12 year-old brother, Bobby, isn’t home. It doesn’t take long for her to realize what he’s up to: The Annual Burmese Python Hunt! That’s right. Here in Florida, once every year, you’re allowed to go out and hunt pythons.

Sharon finds Bobby and yells at him. This is the kind of nonsense that got their dad killed, she tells him. But Bobby tells her how fun hunting pythons is and why can’t she please let him. Sharon is reluctant but she figures if Bobby’s going to be hunting pythons, she might as well tag along to make sure he doesn’t get hurt.

Meanwhile, there’s this giant political backstory going on involving Florida gubernatorial candidate Pam Huntley. It’s discovered that Pam was first eaten by, digested by, then defecated by, a 30 foot long Burmese python. This news coincides with a park ranger being swallowed up by another python. Who’s being hunted here. The pythons or the people???

As the hunt continues, the death continues. But it looks like the pythons are winning! As Sharon’s news reporter mother looks into the cause of the sudden attacks, she finds evidence that the local corrupt politician has been working with a giant Florida pharmaceutical company and that the drugs they’re disposing into the water have turned these pythons into serial killers!

Will Sharon and her brother realize how bad this is in time to get back home and protect themselves from the snakes!? Or is it too late? Have the snakes found their way into each and every home in town!!????

I struggled with this one, guys.

Big time.

I think there were twenty characters introduced before page 10? Do writers realize that readers actually have to remember people? And if you introduce a billion people, there’s no way we’re going to remember them all?

There was also a ton of 5-6 line paragraphs. Look, you can write as many 5-line paragraphs as you want in a script. The reader’s not going to read them, though. You’re not gaming the system by squeezing all that extra information in. People who open scripts expect them to read fast. When the scripts don’t read fast, readers simply adapt their reading style to ‘skim-mode’ so that they do read fast.

On top of all this, this script is titled Reptile Dysfunction. When I open a script titled Reptile Dysfunction, the ratio of work to entertainment should not be 5 to 1. Scripts like this should be the easiest scripts to read in the world.

Yesterday we talked about dead relative backstories. Most movies have them. So it’s a common thing you’re going to be writing a lot. Which means you want to be good at it. You want to understand what works and what doesn’t work and make choices that are right for your screenplay.

In this script, after the opening teaser, we watch old home video footage of two people getting married, having a kid (Sharon), watching the kid grow up, graduate from high school, blah blah blah. And then, somewhere along the way, the dad dies. And we finally get to present day where we are now with Sharon as a young adult.

What that montage did was it created context for our main character, Sharon. We were “there” when her father passed away. The argument FOR this montage, then, is that we feel closer to Sharon than had we not gone through that experience with her. The argument AGAINST this montage is that it takes up valuable script time where we could already be into the story.

It’s no secret around here that people will give up on your script within a single page. Everyone on this site has done it. You have read one of those Amateur Showdown pages and thought, “Nope, not good enough to continue.” A montage like the one in Reptile is not story. It’s not entertainment. It’s not dramatic or suspenseful. All it is is backstory. It’s INFORMATION. When you’re giving people information, as opposed to drama, they lose interest.

Now you may say, “But Carson. What about Pixar’s Up? That started with a montage of two people meeting, falling in love, getting married and one of them dying, and it’s considered one of the greatest scenes ever!” That’s true. But that movie was ABOUT THAT RELATIONSHIP. The whole movie WAS THAT RELATIONSHIP so it made sense to start the movie with the montage of their lives together.

This, meanwhile, is a movie about anacondas attacking a Florida town. It doesn’t need that montage. Yes, I agree that it brings us a LITTLE closer to the main character. But I don’t think it’s worth it when you can just allude to the fact, along the way, that she lost her father.

Screenwriting is so funny. Yesterday was all about a premise that was too simple for its own good. It didn’t have enough meat on the bone. Then you have today’s script which takes a simple premise – snakes invading a town – and approaches it like it’s a Woodward and Bernstein biopic. This is so over-plotted and over-populated, it gets in the way of what the script is meant to do – which is to give the audience a good time.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: When it comes to fun ideas, get out of your own way. Anything that gets in the way of a fun read – long paragraphs, overly complicated plots with lots of jumping around, character counts in excess of 40 people – need to be eliminated. We’re picking up your script with a certain expectation of fun. Just like if someone thinks they’re about to read War and Peace and instead gets The Da Vinci Code, they’re going to be pissed, the same thing is going to happen if your fun-sounding premise reads like a history book.