Just TWO DAYS LEFT to get your scripts in for The Last Great Screenplay Contest. July 4th. 11:59pm Pacific Time. carsonreeves3@gmail.com. I cannot wait to see what you’ve got in store! But first…

Story time!

When I was a wee little tyke screenwriter, long before the days of Scriptshadow, I made a lot of mistakes. In fact, if there was a mistake to be made, I probably made it. But one of the biggest mistakes still haunts me to this day. Not because, if I hadn’t made that mistake, I would’ve sold the screenplay. But because it was embarrassing. I still cringe whenever I think about it.

When I used to teach tennis, I had a tennis student who was high up on the food chain at a certain prestige cable channel. I had been carefully mentioning my writing aspirations to her every few lessons and, over time, she started asking me what I was working on. It just so happened that the genre of the script I was working on was exactly what the channel was looking for at the moment.

So this lesson of mine put her reputation on the line with the head of the company, saying that she had a script from someone that was just what he was looking for. Long story short, there was this very specific time frame where he could read it. She came to me one day and said, “He can read it this Saturday on his flight. This might be your only chance to get it to him.”

Now, for the most part, my script was finished. But, of course, the excitement of this opportunity got to me and I was determined to make the script as good as it could possibly be in the next five days. I came up with an exciting new opening scene, which I wrote. I realized a chunk in the middle of the script would’ve been better served if I moved it up 20 pages. A secondary character I never quite liked was ditched in favor of a brand new character I came up with on the spot. And then, of course, I went through every single scene, rewriting lines of dialogue and lines of description to make them as good as they could possibly be.

I literally finished 20 minutes before I had to deliver the script. I printed it out (yes, this is when we had to print scripts) and raced to my lesson’s place, proudly handing her the script. For the next three days, I dreamed of my ascension into Hollywood and being the hot new screenwriter in town. It wasn’t even a dream. It was manifest destiny.

But then the next week something funny happened. My lesson canceled. And then, the week after that, she showed up, but she avoided any talk of screenwriting with me, hastily scurrying away the second the lesson ended. “Hey,” I yelled, “We still have to clean up the balls!” Next lesson, same thing. Operation Scurry Off. Finally, I just came out and asked her, “What happened with the script?” And I saw her body crumple as if her entire insides had deflated.

She explained to me that her boss “tried” to read the script. “Tried” being the operative word here. But it was so incomprehensible that he gave up after the first 20 pages. Although she didn’t say it out loud, the vibe I got from her is that this lowered her a peg in the company. This man’s time was extremely valuable and she wasted it on a script that wasn’t even ‘not good.’ But a script that was so bad you didn’t even understand what was going on.

Now being a young defensive screenwriter who believed that everything he wrote was genius, I blamed this on “Hollywood bullshit.” He probably wasn’t paying attention. He never gave the script a chance. Because I didn’t have a big agent, he didn’t give me the same amount of respect as he would an “established” screenwriter.

But let me tell you, a year down the road, I opened that script back up. And it wasn’t just bad. It was unreadable. In the moment, all those last-second changes that I’d come up with made perfect sense. But because I never allowed them to sit and never came back to the script with an adequate amount of time passed and fresh eyes, I couldn’t see just how messy the script was.

All of this is to remind you not to make the same mistake I did. When you have a script deadline – whether it be The Last Great Screenplay Contest, the Nicholl, an important contact who wants to read it this Saturday – you have to understand what you can and cannot do when there’s only a few days left. And I’m going to help you with that right now.

First – your script should be finished. If you’re still writing the last act right now, don’t bother sending your script to me. I’m serious. I will hate it. I can guarantee that. The ending is everything. It ties the story together. It’s the payoff to everything you’ve set up. If you don’t even have that written yet, that means there’s so many things you haven’t figured out about your story.

Second – and this should be obvious – don’t you DARE mess with the structure. This is the fastest way to destroy a screenplay with so little time left. Structure always takes the most time. So, if you’re two days away and you see a structural mistake (“The bank robbery scene should probably be moved to the midpoint”), I’m sorry but you can’t change that. It’s going to have massive ripple effects which you won’t realize for a couple of months.

Third, it’s too late to get rid of, change, or add any characters. Even characters with a limited number of scenes. You’re not going to create any character of substance in two days. Don’t mess with that. Trust me.

Next, don’t f$%# with the first five pages. The first five pages will be the most tempting to play with. But more often than not, a change you make in those first few pages is going to hurt you. A new first scene can change the way the whole script reads. We just talked about this with The King of Staten Island. Originally, the first scene of the movie, Pete driving his car with his eyes closed, was in the middle of the film. They decided to put it at the beginning and it gave you a much better feel for who the character was. But they tested that change. They had people watch both the old and new version before they committed to it. You’d be throwing in a new scene at the last second and hoping it works. That’s not a good strategy when sending a script to anyone.

Next, stop rewriting any lines in the first ten pages – any description, any dialogue – don’t rewrite lines. The chances of you misspelling a word go up 500%. I know this because every time I change a sentence right before I post an article on Scriptshadow, those are ALWAYS the sentences with the misspellings in them.

So what can you do? Proofread. That’s all you should be doing with two days left. Make sure the sentences read cleanly and don’t have any mistakes in them. All your creative work should’ve been done by now. It actually should’ve been done two weeks ago. If you see a truly glaring error that requires you to rewrite a page or a scene… I mean… I guess you can change it. But those changes have a much better shot at hurting you than helping you.

Art is a weird thing. Any change needs time before you can see it objectively. So if you’re rewriting anything of substance this late in the game, do so at your own risk.

A screenplay is not a school assignment where there’s this romanticization of barely finishing the paper on time and getting it to your professor with just minutes to go. A screenplay is your lifeblood. It’s your story. It’s your emotion. It’s what’s inside of you. It’s supposed to be the most beautiful representation of your self-expression that you can achieve through this medium. Therefore, it should be the best you can possibly make it. If you’re having to change scenes with two days to go, your script probably isn’t ready for consumption yet. I want to see your best. Not your rushed best.

Good luck to everyone. I can’t wait to see what you’ve written!

Chronicles of Narnia meets The Most Dangerous Game and the power of a great concept

Genre: Fantasy/Thriller

Premise: Two hunters pay a strange mischievous man to travel into a world where you can hunt the creatures of fairy tales.

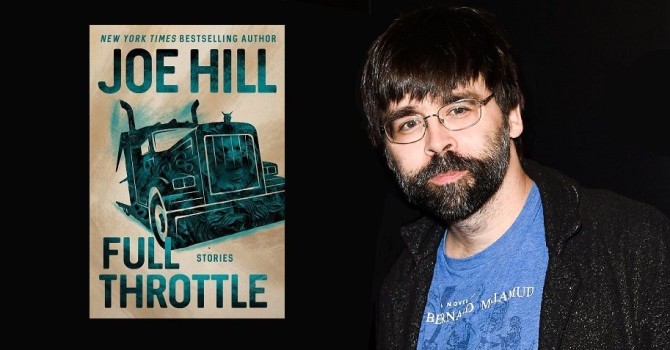

About: This short story by Stephen King’s son, Joe Hill, spawned a huge bidding war last year that Netflix threw the most money at. The short story can be found in Hill’s book of short stories, Full Throttle. It is being adapted by Jeremy Slater, who created The Umbrella Academy (for, yes, Netflix)

Writer: Joe

Details: Roughly 75 pages

I love big ideas!

We don’t get enough of them anymore.

This is a big idea. And it rides that elusive “same but different” line perfectly. It feels both familiar and fresh. If I could figure out what the secret sauce is to achieving that balance, I would be a billionaire. Instead, I see a bunch of ideas that are too much the same or too far out there.

“Faun” feels like a script that would’ve hit the market during the spec boom. And, no, it didn’t have to be a short story to get purchased. This is something that would’ve worked as a spec. That’s how good the idea is. So take heed – any one of you can sell a script if you come up with an idea as good as this.

The story follows a pharmaceutical billionaire named Stockton who loves to hunt big game. He’s friends with a “regular guy” named Fallows who also likes to hunt. Fallows used to be in the military so he’s seen his share of bloody spectacle.

The two are joined in Africa by their 18 year old sons, Peter (Stockton’s son) and Christian (Fallows’ son) to hunt some big game. Fallows ends up bagging a lion and then they all go back to Maine where Stockton has arranged a meeting with Mr. Charn, a strange middle-aged man.

Mr. Charn explains to Fallows that he runs a secret game-hunting business himself. But that it’s only available twice a year and it costs 250,000 dollars. Fallows is, of course, skeptical, even though Stockton’s already gone on this journey himself. So Mr. Charn shows a video tape of two men hunting and killing a “fawn,” which is a man with horns and blue furry legs.

It takes some convincing but Fallows eventually realizes it’s the real deal so he’s in. The next day the five of them go through a small door in Mr. Charn’s house. This door is the portal to this world. It is only open 2 days a year. The rest of the time, it’s a crawlspace. And, once you’re in the world, you need to be back by the end of the day or you’ll be stuck here for 9 months. And it won’t be you doing the hunting then. It’ll be them.

“Them” consists of every weird creature of lore you can think of. Fawns, fairies, centaurs, cyclops, and other monsters that have no names. It all seems impossibly perfect. The chance to kill something that only a handful of people on earth have ever killed. But Fallows soon learns that this land is unlike any he’s seen before and that even the tiniest mistake could result in death.

Joe Hill’s writing isn’t nearly as accessible as his father’s. Here’s the third paragraph of his story: “The baobab was old, nearly the size of a cottage, and had dry rot. The whole western face of the trunk was cored out. Hemingway Hunts had built the blind right into the ruin of the tree itself: a khaki tent, disguised by fans of tamarind. Inside were cots and a refrigerator with cold beer in it and a good Wi-Fi signal.”

The only thing I understood in that paragraph was beer and wi-fi. And this sort of scattershot writing style constantly creeps into Hill’s work. It’s not unclear. But it never feels as clear as it could be.

There was one point, early on, when our characters kill a lion. It’s a long scene. And, at the end of it, the lion leaps back up and nearly kills them. But Fallows is able to shoot it dead. It turns out the lion wasn’t as dead as they thought.

Then, after this, we get the line, “The Saan bushmen roared with laughter.” Ummm, what? This was the first time I was hearing of any bushmen. And the scene was 25 pages long. And, also, this isn’t exactly a moment that you would laugh at. They were all milliseconds away from dying. You’d get moments like that that were frustrating. If there’s bushmen around this whole time, let me know!

However, “Faun” survives this pitfall because the idea is so good. It’s a lot harder to screw up good ideas. Because what’s going on in producers and agents heads when they’re reading good concepts is, “That annoying part doesn’t matter because I can totally see this as a movie.” Contrast that with a dumb part that happens on some introspective character-driven indie script with no concept. That will usually end your chances with the agent right there.

What I admire most about this story is that it navigates the contradictory nature of its concept with ease. When you write a script like this, you’re basically asking the audience to root against your characters. It’s the same thing as a Friday the 13th movie. We’re rooting for Jason to kill them all. And that’s a lot harder to pull off than a traditional hero-driven story because you’re trying to make us stay interested in people we want to die.

Ideally, you want the middle ground. You want good people to be forced to do bad things. Like Breaking Bad. Or like the new project Edgar Wright signed onto, The Chain. That’s about people who just had a child kidnapped being forced to kidnap a child themselves in order to free their kid. It’s good people being forced to do a bad thing.

That’s not the case here. These are all bad people. They want to kill animals. They want to kill actual intelligent creatures. There’s nothing to root for with them. I’m actually surprised that Hill didn’t make one of the children reluctant. That would’ve given us someone to latch onto. But both Peter and Christian want blood as much as their fathers.

While reading this story, I had it at a double-worth-read. And then something happened that turned it into an impressive. Before you read on, I want you to imagine what might happen in a story like this for me to raise my ranking up to the rarely-given ‘impressive.’ What would you do with this story to get it there?

What Hill did was he didn’t rest on his laurels. He had plenty to work with already. He had an entire world full of unique creatures. However, what he did was set the characters up at a camp to prepare for the hunt, and then, just as they were about to go off, Fallows jams a knife into Stockton’s face and shoots Peter in his forehead.

At that moment I thought, “Now we have a movie.” We already had a movie. But this is a great writing move. You put all the focus on the outside danger, which makes the twist of “danger from within” that much more shocking. That really upped the ante of the story because now, in addition to having such a cool idea, I had no idea where the story was going to go. Which is exactly where I want to be as a reader.

This is a nice reminder that high concept ideas are not dead. They are alive and well. So, by all means, look into that idea notebook of yours and see if you have a couple of these stashed away. Even if they’re expensive. If they’re as good of an idea as this? And the writing is solid? It will sell. I can pretty much guarantee it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Don’t cross the river!” I love this screenwriting tip. It always works. When you stick your hero unwittingly in the haunted house, have someone say, “Whatever you do, don’t open the red door by the bathroom.” And, the rest of the movie, we’re going to look forward to what’s behind the red door. Here we get the same thing. Mr. Charn warns Fallows and Stockton that, whatever you do, don’t cross the river! It’s dangerous over there. So guess what we’re looking forward to? That’s right. We’re on the edge of our seats to see what happens when they cross the river. “Don’t do [blah]” is a great way to create some anticipation in your reader.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A subversive superhero story about the world’s only superhero living a bachelor lifestyle, learning he has two very different teenage twins he never knew existed, and now has to figure out how to be a father.

About: This script made last year’s Black List with 8 votes! This is the writer’s big breakthrough script. He is a copywriter in Los Angeles.

Writer: Sean Tidwell

Details: 106 pages

You guys know I’m all about subversive superhero scripts. Whether you love it, hate it, can’t stand it, or want to marry it, superheroes are the biggest thing going on in theaters these days. Or, three months ago at least. These days, no movie is doing well in theaters. Now that I’m thinking about it, I wonder if there’s a perfect script to write for the coronavirus era. A movie that takes advantage of the new, very specific, reality of what moviegoing will become. Feels like there’s an opportunity there. But I’ve gotten off track.

Right, so superheroes. Whenever there’s a behemoth of an industry, there is an opportunity to make money on smaller ideas that orbit that industry. iPhones make Apple a bagillion dollars. But they also make a lot of smaller companies who offer add-ons for iPhones a lot of dollars. Same idea with these superheroes, aye. The right idea that indirectly explores superheroes would make producers’ heads explode. Because you get a superhero movie without having to pay that hefty IP price tag.

The problem with these ideas that I’ve seen so far is that they haven’t been that clever. The Boys has done the best job so far. Then again, it’s not an original idea. It’s based on a real comic. That spec that sold last year about a heist where the characters realize they’re inside the home of a superhero sounded fun. But I haven’t heard anything about it since.

Super Dad sounds like something a bored Vin Diesel might attach himself to. But, as we’ve all learned on this site, it comes down to execution. A good concept helps. But it’s what the writer does with the characters and the plot that matter most. Can Super Dad pull off the unlikely and overcome its familiar premise?

We meet Layton Wade as he saves a young girl falling from a crane on top of a building. When he lands, he reaches out and a Gatorade appears. Layton isn’t a real superhero. He’s just acting! But wait, then the real crane falls! Layton runs over and catches it before it mauls the crew. Layton really is a superhero!

Layton is also a player. And a big drinker. And hasn’t grown up. 13 years after that commercial, at 40 years old, he’s still partying with local sports stars from the Los Angeles Rams and drinking til the early morning hours. And even though he’s having some issues accepting middle age, he wouldn’t trade his lifestyle for the world.

So he’s not thrilled when a social worker comes to his Iron Man like Los Angeles mansion and tells him that twins, 13 year old Will and Anna, are his kids. Some girl he had sex with 13 years ago died. So Layton has become the lone guardian. And he ain’t happy about it. He tries everything in his power to get the social worker to take them back but fails.

Layton is thrust into a life of parenting, a life he does not enjoy. He’s got to take these two to middle school. As in: HIM. Layton. Superhero. Has to drive kids to school. It’s so beneath him. This isn’t fostering a lot of love from his kids, who are beginning to hate him.

Meanwhile, there’s a woman named Scarlett – she actually asked Layton to invest in her company 13 years ago on that commercial set – who is on the verge of becoming the next Google. That’s IF her metal exo-skeleton suits created to help disabled children work. She’s oh-so-close to the finishing touches but the funding has run out and she’s getting desperate for the money she needs to achieve her dream.

Not so coincidentally, local criminals Layton is assigned to stop are wearing metal exo-skeleton suits, creating the first humans he’s encountered who are as strong as him! Why is Scarlett targeting Layton? Will Layton learn to parent? Oh, and when Anna and Will’s aunt offers to raise the kids, what will Layton do? Will he go back to his awesome bachelor lifestyle? Or will he finally accept the responsibilities of becoming an adult?

These are actually really hard scripts to pull off. You’re writing to the lowest-common denominator in terms of discernment (kids and their parents). But you still need to write a good enough script to impress the Hollywood gatekeepers. Not to mention, it’s hard to write something funny when the humor needs to be this safe.

So color me tickled that Super Dad pulled it off!

This script was actually really good. And if I sound surprised, it’s because family comedy scripts are often the worst, the cinematic equivalent of Fuller House.

But the writer managed to write a bunch of funny scenarios and moments. Couple that with an easily likable hero and a well thought out plot, and you have yourself a winner.

I knew the script was in good shape when the Aunt plot point emerged. These kids are thrust upon Layton and he’s forced to take them. But, after a couple of days, the social worker calls back and says their aunt is willing to take them. But she’s out of the country for a month.

This is a small thing but this is what good screenwriters do. Not only does, “You can give the kids back after a month,” introduce a BIG CHOICE that the hero will have to make at the end of the film (It’s always better if your hero has a choice), but it subconsciously structures the story for the reader. The reader now knows that’s the time-frame. In a month, he’s either going to keep the kids or get rid of them.

Another thing I liked was that he inherited twins. In every other iteration of this idea, it’s one kid who shows up. Of course, that makes total sense, since the one-night stand scenario only allows for one kid to have been born. By making it twins, it puts a subtle twist on the formula that makes this just a TEEEEENSY bit different. And that’s all you’re trying to do with a script. You’re trying to add these little twists to common scenarios so your script reads differently from everyone else’s.

But the big thing is that the script is funny. I laughed a lot. There’s a scene where Layton is with his kids and he gets a call that a bank is being robbed. This forces him to go stop the robbers while leaving his kids outside. During the battle, his car gets destroyed, and, afterwards, he doesn’t know what to do. So Anna calls an Uber. And she accidentally calls Uber Pool (they came from a poor family so that’s what their mom always used to call). We get this funny moment where the most famous man in the world is riding home in a car filled with his kids and several Uber passengers.

There’s also a moment where Anna has her first period and Layton has to go buy tampons. This is his worst nightmare. He’s terrified of being seen shopping for tampons. He doesn’t like the idea of his daughter becoming a woman. So the whole thing is giving him major anxiety and, while it’s happening, a shopper walks into the aisle and is so shocked by seeing Layton that she drops her cranberry juice, which shatters on the white tiled floor, forming a big red horrifying blotch right in front of Layton.

But the biggest achievement is that Layton is fun to be around. Even though I’ve seen it all before, it’s fun watching him try to parent. His kids go to school. His daughter tries to make a football team of all boys. His son is an anime dork who’s crushing on a girl and doesn’t know how to ask her out. Layton becomes determined to help them. And, in the process, starts to love them. It’s all a bit cliche but the smart and funny execution is a cut above all the other scripts I read in this genre. It’s good stuff.

I want to finish off by alerting you to one negative, however. This is something that’s rarely discussed in screenwriting because it’s so specific. However, it’s worth noting because I do see it happen quite a bit.

This is using your opening scene as a big reveal when the big reveal only works in theory and not in practice. So the opening is scene here is pretty clever. We get a scenario we’ve seen a thousand times before. A damsel (in this case, a girl) is in distress, hanging onto a crane at the top of a skyscraper, losing her grip and falling, then Layton flies up and saves her, then when he gets down on the ground, we pull back and see it’s a commercial. Layton is not a real superhero. He just plays one.

While the crew members rush in to do their jobs, Layton talks to his agent. As this is happening, the crane on top of the building, which is real, breaks and falls down. Just as it’s about to hit everyone, Layton runs over and catches it to save them. It’s a double-twist. Layton really IS a superhero. Clever, right?

Here’s the problem. We already knew that. The title of the script is Super Dad. And, chances are, we didn’t read this script without hearing the pitch or reading the logline. And, if this script is so lucky as to become a movie, we’ll have seen all the advertising and know he’s a superhero going into the film. Which means this scene will play out as… “Well, yeah, duh. We already knew that.”

What does this mean? Because this scenario comes more than you’d expect in screenwriting. People are going to know important information about your script before they’ve read it. You’re probably thinking, “Well then we won’t tell them what the movie is about so everything is a surprise!” But if you don’t tell anybody what your script is about, no one’s going to want to read it.

How big of a problem is this? Not gigantic. Readers might read this scene and still think it’s cute, even though they already knew the reveal. But in a business where every line of the first five pages matters so much, it’s something you want to keep in mind. I’m not saying never do it. But if you really want to surprise the reader in that opening scene, you should probably write a scene whose reveal isn’t something we already know.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You can subliminally (or not so subliminally) imply who you want the reader to imagine in a role by using a real life actor’s name. This tends to work fine in comedy but it’s a little tougher to pull off in serious genres. Here the villain is named Scarlett. No doubt you’re expected to think of a certain red-headed Marvel Avenger.

Genre: TV Drama 1-hour/Supernatural Thriller

Premise: A struggling actor whose girlfriend threatens to leave him if he doesn’t find a job, robs a bank, but in the process inadvertently switches bodies with the bank teller, allowing for a unique type of getaway.

About: Jordan Peele’s Twilight Zone series on CBS’s streaming service had a rough first season, with, arguably, no breakout episodes. Maybe that’s why the second season, which dropped this weekend, came in with so little advertising. But I still like the idea of a Twilight Zone series and wondered if Peele could learn from last season’s mistakes. I went to IMDB and found the highest rated episode (Episode 3, at a 7.4) and checked it out.

Writer: Win Rosenfield (created by Jordan Peele) (originally created by Rod Serling)

Details: 44 minutes

As you’ve heard me say before, I’m looking for a Twilight Zone type script (or two) to produce. Why? Well, a Twilight Zone idea exists in a genre that can have a big juicy concept and can be shot cheaply. It also allows you to remain marketable outside the horror genre, which is music to the ears of writers who detest horror.

However, I’m realizing after watching this Jordan Peele Twilight Zone how easy it is to get The Twilight Zone wrong. Today, I felt, was a good day to identify what they’re doing wrong on this show and how one might course-correct Peele’s errors.

Something I noticed right off-the-bat was that the ideas felt dated, at least with today’s episode and many of the episodes I saw from first season. Usually, it’s a good idea to respect the source material. But Black Mirror changed the game. It’s like they said, “What if we did Twilight Zone, but with technology and a more current approach to storytelling?” This made Black Mirror feel like The Twilight Zone 2.0. Heck, with Bandersnatch, they went 3.0. Peele’s new Twilight Zone feels like Twilight Zone 1.2. It’s very much stuck in the past.

Take today’s episode, “The Who of You.” Harry Pine is a Tootsie-like actor. He can’t catch a break and is starting to detest auditions. To make matters worse, his girlfriend can’t stand being around him. The rent is due and, once again, Harry doesn’t have the money to pay for it.

So Harry takes a rather drastic approach at solving the problem. He grabs a bag, walks into a bank, and attempts a good old fashioned stick-em-up robbery (did I tell you that this concept was dated?). However, in the process of the robbery, both Harry and Female Teller lock eyes and, boom, all of a sudden Harry is inside the Teller. Neither Harry or the woman (who’s now in Harry’s body) know what happened, but it doesn’t take Harry long to figure it out. He takes the bag of money (as the woman) and runs.

When a cop comes in the back door and spots the Teller running, he stops her and, once again, Harry locks eyes with the cop and transfers into *his* body. Harry, as the cop, takes the money bag with him and runs off. Meanwhile, ultra-macho Detective Reece comes to the bank and arrests “Harry,” who’s actually the bank teller woman in Harry’s body.

The cops sense that something is up and they start hunting Harry (in his cop body) down. But Harry has now perfected his body-jumping technique. He jumps into a barista then a jogger’s body before heading to a psychic to figure out how all this is happening.

The psychic is onto him, gets angry, then boots him out of his place. During their fight, Harry forgot to grab the bag of money! Now he’s locked out of the store. With his new power, however, Harry figures out who lives in the apartment above the psychic store and jumps into the bodies of people in the building until he gets into a little boy’s body who lives in the above apartment.

He then slips down into the psychic store to get the money back but is met by Detective Reece and whoever’s currently in Harry’s body. Detective Reece has seen enough to realize something supernatural is going on here so he knows the real Harry is in the kid’s body. Harry then does a Jedi-Level triple body swap move so he’s now in Detective Reece’s body and Reece is in Harry’s body. This makes for an interesting showdown when a squad of cops bust into the store at the last second, guns drawn.

The Who of You is a harmless fun episode. I liked the acting exercise component of it. This is a dream scenario for actors as they all get to play the lead character and they don’t usually get to play characters this varied.

I also enjoyed figuring out the rules. Obviously, I knew who was in who’s body after the first switch. But with each additional switch it became harder and harder to figure out who was who. But not in a frustrating way. It was exciting realizing how the chain of switches evolved and who was getting stuck back in who’s bodies.

Despite this, The Who of You (is it just me or does that sound like the title of a Dr. Seuss book?) still feels like a dated premise. This episode could’ve been shot in 1910, right after that famous horse film was made. That’s how back of the closet the concept is. And it’s the series’ achilles heel.

Peele seems to respect the source material so much that he’s reluctant to change it. Not only does this affect the concepts he chooses. But it affects the tone. Those original Twilight Zone episodes were from a much simpler time where TV was new and the world wasn’t nearly as complex as it is today.

The other day I was listening to some music (Jack Garrat – Circles) and it occurred to me that was the fifth song I’d heard *that week* about anxiety. I don’t think anxiety was even a thing in the 50s. But it makes sense. You don’t get any time off in 2020. There’s always a new e-mail, a new text, a new Youtube video, a new social media feed to check, a new news story. You’re always being called on by something, so of course you’re anxious. Back in the 50s and early 60s you didn’t have anything close to that level of overload.

That made an episode about people with pig-faces intense heady stuff at the time. But we’re way past that level of intensity. We require concepts with more weight, like Black Mirror Season 3’s San Junipero, another episode that plays with body-jumping but in a profoundly more interesting way. Here in Peele’s universe, the body jumping is a gag, a goof, a bouncing ball to follow along with. It’s harmless fun but I’m not sure this genre works as harmless fun anymore. There have been too many supernatural stories inspired by The Twilight Zone over the years that have elevated the genre. Peele needs to keep up.

Despite all this, the episode *does* work. As much as I’m dogging the complexity, they do try and explore Harry’s character some. There’s this question of, “Who am I really?” And experiencing how people see you differently depending on what body you’re in. And there’s this fun little subplot where all of this is helping him become a better actor. It’s not Black Mirror level introspection but it’s enough to keep things entertaining.

To answer my original question. How do you write a Twilight Zone film that resonates in 2020? I think it’s all about depth. You can’t use a concept that’s too gimmicky, like this one. Or, if you do, you have to explore the character elements more and not get hung up on the theatrics. The Sixth Sense is a good example of that. A psychiatrist who’s lost his way after a patient’s death tries to find his way back by helping convince a young child that he doesn’t see ghosts. Without that element, you just have a kid who sees dead people and that’s not going to resonate with audiences as much.

I know Peele finally wrote an episode (Ep 2) this season (he didn’t write or direct any of last season). So I may check that out. But if that doesn’t work, it might mean sayonara to CBS’s new Twilight Zone series for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Today’s What I Learned is not about today’s review, but rather a question for all of you. I’m curious what the most helpful screenwriting tip is that you’ve learned from the site. While I know what *I* think are the most important screenwriting tips, I realize that everybody prioritizes things differently and it might be fun to put a post together with all the best reader-inspired tips/lessons. So, it’s time I learned from you. What is the most important screenwriting tip you learned from Scriptshadow???

This is not an official post. The following thoughts you read will not be coherent. This show does not deserve coherent thoughts. But since there wasn’t going to be a post today, I thought I’d give you my stream-of-conscious thoughts on Ozark Season 3. A TON of people recommended this season to me. To the point where I was expecting one of the all-time great seasons of television.

That is not what I got.

What I got was shoddy writing, awful acting, and an all-around disaster of a season. But let me start with the good. The bi-polar brother character was good. His storyline worked. But he was the only storyline that worked. Everything else ranged between bad and terrible.

The thing that frustrates me most is that no one on this show knows how to write towards a goal. The season started out with a plan. The Byrds buy a casino boat they can launder money on. Okay, that’s something we can use to build a storyline around. But by the fifth episode, the casino had become background noise, something the Byrds occasionally went over to and checked on.

By the way, I’m three seasons into a show about money laundering and I still don’t know how money laundering works. And I’m positive that half the writers on this series don’t know either. Whenever money laundering is brought up, it’s done so in general terms. Some character over in the corner is doing it. Or if Marty is doing it, he keeps to himself about it. There’s never any explanation of how much money is being laundered or what the ultimate goal is other than there’s some guy in Mexico who “needs his money laundered.”

Speaking of Marty, HE HAS NOTHING TO DO ON THE SHOW!!!! The only purpose of this character is to come into a scene when two other characters are arguing and say, “Guys! Guys! We need to focus here. Okay?” I swear he said a variation of that line six million times in the season. Isn’t Marty supposed to be your main character?? Why doesn’t he have anything to do!

In Marty’s one big episode, that I call, “The Laughably Awful Excuse for a TV Episode” episode, Marty is kidnapped and taken to Mexico so the big drug cartel guy can scare him a little. The awfulness of the writing was confirmed to me when they cut to Marty, in a cell, ravenously ripping rice off a bowl with his bare hands, jamming it into his mouth, desperate for food. The problem with this moment? Marty had only been in Mexico for a FEW HOURS!!!! And he’s already starving to the point where he’s ripping food off bowls. It’s classic amateur writer hour. They want all the drama and none of the logic. It’s probably going to take your character longer than a few hours to be starving. This sequence is intercut with some faux important flashback of Marty as a kid waiting in the hospital when a parent is dying and he keeps playing one of the video games down in the waiting area. I’m sure to the writer, this video game had a ton of significance. It was symbolic. It was a metaphor! To us, it was, “WHY THE F%$# ARE YOU FOCUSING SO HARD ON THIS RANDOM STUPID VIDEO GAME??”

Oh, and don’t get me started on Ruth. The actress who plays that character is one of the single worst actresses I’ve ever seen allowed on a professional TV set. She makes the wrong choice on EVERY SINGLE LINE she reads. It’s clearly meant to be read one way and she, without fail, always emphasizes the wrong word or says the sentence the wrong way, completely killing the meaning of the line. It’s actually quite spectacular that you can make the wrong choice that many times in a row. And I didn’t keep count, but she says the word “f%$king” at least 1000 times over the course of the season. It’s one thing to keep a character’s verbiage consistent, it’s another to be plain lazy. Give the character SOMETHING to say other than “f%$king” every single time she opens her mouth.

But I soldiered on. I kept going. Because everyone said the ending of the season was great. I figured this had to all come together somehow. That something world-changing was going to happen.

I guess (spoiler) everyone was talking about the fact that they killed off the brother. And that was a nice moment. But I was expecting more.

And the baffling part about that is they killed him in episode 9. So episode 10 rolls around, after all the air had been let out of the balloon, and as a result they had NOTHING TO DO IN THE EPISODE. It was like watching a real-time 60 minute car crash. It was clear the writers had no idea where to go or what to have the characters do. Every scene was characters either standing around outside discussing something that had already happened or sitting down inside discussing what already happened.

YOUR FINAL EPISODE SHOULD NOT BE ABOUT WHAT ALREADY HAPPENED! IT SHOULD BE ABOUT WHAT’S HAPPENING NOW!

I couldn’t believe what I was watching.

And look, I’m not here to tell anyone who loved this season that they’re wrong. I get that when you become attached to characters as an audience, you don’t see the same flaws other viewers do. So if you cared about these people, your experience was likely different. The only person I cared about was the brother. But every other character was so poorly written (except for Wendy and the lawyer lady at times) that I couldn’t muster even a microcosm of interest in what happened to them.

I feel like I spent 10 hours watching a show where two things happened. You watch a season of Breaking Bad and a million things happen.

I don’t get it. Sorry. I had to get this out of my system.

Curious to hear your reaction. :)