Today’s screenplay poses the question, “What if you could date Hal 9000?”

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a whirlwind long-distance online romance, a once-cynical writer inherits a remote smart-house from her newly deceased new husband and discovers he might not be entirely gone after all.

About: Lauren Caris Cohan is a writer-director and this is going to be her directorial debut. This script finished with 8 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Lauren Caris Cohan

Details: 112 pages

Last week was Fun Script Review Week.

We had two interesting scripts to talk about.

Will that trend continue this week?

Only time will tell. However much time it takes to get through the plot description.

The evil smart house concept is not a new one. About 15 years ago, the concept of a smart house entered the media, igniting many screenwriters to write Smart House horror scripts. I think a few of them even became movies.

But when the smart house the world promised us never came to be, people forgot about the idea. Until now. To Cohan’s credit, it’s a good time to explore this idea as we really are moving towards those concepts first imagined 15 years ago. I can turn on the lamp over by the window by yelling at Alexa to do so. And my bedroom Alexa tells me every morning how many people died from Corona virus in the last 24 hours. And some argue technology hasn’t made the world a better place.

I’m a little wary, though. How much danger can a smart house really create? I’m pretty sure by walking to the middle of the living room, Crazy House AI can’t touch you. But isn’t that the challenge of writing? Every idea has limitations. Good writers are able to find solutions to those limitations. Other writers are not.

Sheila is a 42 year-old British woman who may have stolen my quarantine to-do list since she’s apparently been watching a lot of 90 Day Fiance. Without ever having physically met Michael (she’s only talked to him online for the last 6 months) Sheila flies over to the U.S. and marries him. Immediately they head off to Michael’s lovely home in Big Sur.

Michael is rich, retired, and really into nerdy stuff. His entire house is automated. Sheila, a writer, starts working on her latest book, only to get a surprise visit from the cops. Michael’s car flew off a cliff and he died. Poor guy.

A week later, Sheila receives a white box from a company called OUROBOROS. The Ouroboros module allows Michael, whose consciousness has been downloaded to a computer, to come back to life as the home’s AI!

Sheila is weirded out at first. But after visiting Ouroboros and being assured that this is all above board, she allows Michael to come back, because what woman wouldn’t want her husband looking over her shoulder 24 hours a day? Sheila is happy for a while. But then she meets the studly local convenience store owner, Caleb. Yumma yumma.

The two clearly have chemistry but because Creepy AI Michael watches everything Sheila does, she can’t spend any meaningful adult time with him. But when she can’t ignore the need for physical connection any longer, she turns Michael off and Caleb comes over for dinner.

Sheila doesn’t realize it. But she’s just Microsoft Dossed her lover. The next day, while Sheila is out, Creepy AI Michael locks him in the freezer! And when Sheila returns, he locks her in the house as well, informing her that unless she changes her behavior, he’s going to provide the cops with irrefutable evidence that she murdered him for his money. Will Sheila wise up? Or will she burn this place to the ground?

“Aftermath” wasn’t a bad screenplay.

It just didn’t do anything exceptional in the execution.

I knew the script was in trouble when I saw a 7 line paragraph on the first page. In Cohan’s defense, I’ve seen good scripts with 7 line paragraphs in them. But even most beginner writers know that you don’t pull out a 7 line paragraph on the very first page.

The bigger issue with Aftermath is that the structure isn’t there.

When you go to a movie about a controlling killer house, what do you expect to see? I’m guessing you expect to see a controlling killer house. But the house doesn’t do anything controlling or killing until page 80.

That’s partly because Cohan had to do a lot of setup here. We had to establish this complex relationship where they met online and got married and they’re going to Michael’s house for the first time and the house is a smart house. That took a while to explain.

But the rest of the structural problems are on the writer. We spend a lot of time with Sheila heading to the city to meet with Ouroboros and asking them questions. You have a confined thriller set up. You shouldn’t be allowing your heroine to run around, willy-nilly anywhere on the planet. That’s the opposite of what you want to do with this setup. It creates a sense of freedom. It makes the audience think that Sheila can leave safely whenever she wants. Not to mention, you’re sending her out for the least dramatic reasons possible – so you can feed more exposition to the reader. If you’re going to break protocol in a screenplay, you want to do it because you have an entertaining scene idea. Not 20 Questions with a Scientist.

Another problem is there’s no sense of Sheila’s life before she moves here.

This is a common mistake beginners make so I want to discuss it. We often pick characters who don’t have a lot of friends or family because we just want to focus on our main characters. But that usually catches up to you. Take Sheila, for example. We’re supposed to believe that Sheila has no family, no friends, nobody she talks to. Her job history is limited at best. That’s not a real person. That’s a lazy writer.

That’s someone who doesn’t want to give the character a real job because that means figuring out what that job is. Which means it may shape our hero in a way we don’t quite like. It means figuring out how long she’s had that job. If she likes that job. If getting that job was part of her life plan. If it wasn’t, where did things go wrong? It means knowing who she worked with. Some of those people would likely be friends. Why do all that when you can just not do it? Not doing it is easier, right?

But I promise you this. If you’re making a decision in a script because it means less work for you, 99% of the time your script will be worse for it.

I especially get suspicious when a character’s job is writing. A writer will often make this choice for two reasons. One, the writer knows this job well. And two, you don’t have to give a writer any responsibilities or have them need to be anywhere ever. This provides a false sense of security because now you don’t have to worry about a character’s schedule or have them be anywhere. You have total freedom. Which is also why it’s a bad idea. Total freedom is the opposite of everyone who’s going to watch your movie. They all have jobs. They all have lives. They all have friends. So watching some person who’s sitting around all day doing nothing is going to be both un-relatable and unentertaining.

Stephen King makes all his characters writers but Stephen King would be the first to tell you he does this because he’s lazy. And also, he’s one of the most creative people ever. So he’s able to make up for it.

All of these things resulted in a script that was too laid back. This thing never got out of third gear and spent most of its time in second. You have to at least hit fourth gear in your movie. And, preferably, you should have a couple of fifth gear moments.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the biggest sins you can commit as a writer is promising a cool concept then not exploiting what’s unique about that concept at all. This is a movie about an evil smart house. The most original thing the smart house does to attack its occupants in “An Aftermath” is lock someone in a freezer. That’s like if Jurassic Park had a single dinosaur scene where a stegosaurus stole the hero’s spaghetti.

Today Carson does the unthinkable. He makes the argument that character development is pointless in an action movie (Okay, he doesn’t go that far but it makes for good clickbait)

Genre: Action

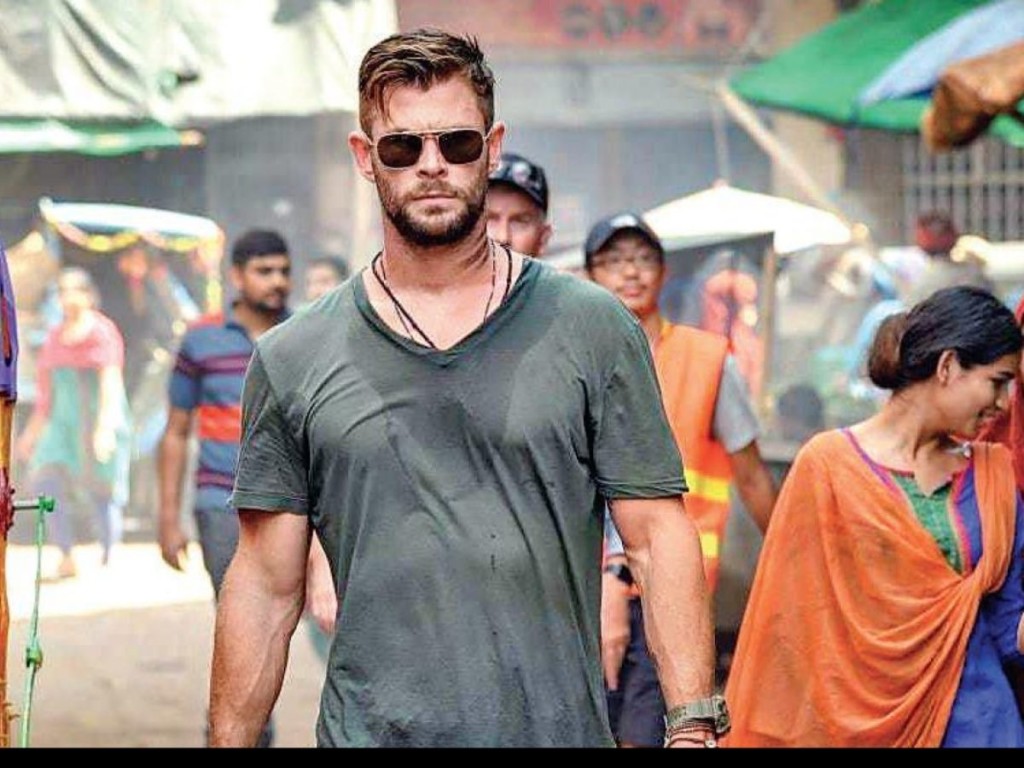

Premise: (from IMDB) A fearless black market mercenary embarks on the most deadly extraction of his career when he’s enlisted to rescue the kidnapped son of an imprisoned Indian crime lord.

About: Here’s writer and producer Joe Russo on how this film came together: “So we were doing Community on TV, and wanted to transition to features with this and thought the smartest thing to do was take this idea we had around an extraction, with this damaged central character, and turn it into a graphic novel. That gave us a visual document that was easy for a studio executive to pick up during their lunch hour and understand what we were trying to accomplish. A long journey writing and rewriting later, we had conversations while shooting Infinity War and Endgame with Hemsworth and Sam Hargrave, and when we put the movie together, that’s when Netflix came into the conversation.”

Writer: Joe Russo (based on his own graphic novel)

Details: about 2 hours long

Extraction may have just done for stunt coordinators what Quentin Tarantino did for video store workers. After Chad Stahelski and David Leitch showed the world the untapped potential of stunt coordinators with their breakout feature, “John Wick,” Sam Hargrave has now proven that the path from stunt coordinator to director is no fluke. His knack for coordinating action has resulted in one of the best action sequences I’ve ever seen.

But outside of his nutso single-take set piece for the history books, was Extraction actually a good movie? Or is it just the world’s best action movie resume for a director looking to impress the studios?

Let’s begin with the plot. I never understood exactly what was going on in Extraction. I knew that Chris Hemsworth had rescued a rich 12 year old Indian boy from some bad people who had kidnapped him. And I knew that some other badass Indian dude wanted the kid and was chasing Hemsworth throughout the movie. But I couldn’t tell you any of the other parties involved beyond that. Which is why I’m glad there’s Wikipedia. Here’s what they say…

Tyler Rake, a black-market mercenary and former Australian Special Air Service Regiment, is recruited by fellow mercenary Nik Khan to rescue Ovi Mahajan Jr., the son of India’s biggest drug lord Ovi Mahajan Sr., from Dhaka, Bangladesh because he is held for ransom by Bangladesh’s biggest drug lord, Amir Asif.

Whilst Rake is in the process of extracting Ovi from his kidnappers, Saju, a former Special Forces soldier and Ovi’s father’s chief henchman, attempts to bring the boy back, doing so in fear of his family being killed and in order to avoid paying the substantial ransom money, which neither he nor Ovi’s currently incarcerated father can afford.

(Kudos, by the way, to Joe Russo for creating the most action hero name ever)

Our boy Tyler Rake is able to secure the kidnapped boy easily and begin his extraction. But on the way to the checkpoint, he’s ambushed, forcing him and the boy into the heart of Bangladesh, where he’s relentlessly hunted down by this Saju guy. It seemed to me like they had the same goal (get the boy back to his dad) so I don’t know why they were against each other. But what are you going to do? It’s a Netflix action movie.

For the longest time, I’ve been obsessed with this topic of how to make an action flick stand out on the page. Or, more specifically, how do you make “generic” interesting?

Because the reality is almost every straight action movie is built on a generic premise. Taken – save my daughter. John Wick – Take down the Russian mafia. Extraction – Extract a kid from the bad guys.

Action is such a generic genre that a fight scene that takes place in a bathroom can be heralded as a step forward for the genre.

Here’s the truth of the matter. The two elements that have the biggest impact on action are a) the directing and b) the casting/acting of the lead actor. You can see what Liam Neeson and Bruce Willis did for Taken and Die Heard respectively. And you can see how much Chad Stahelski and David Leitch elevated John Wick with their action choreography.

The thing that elevates Extraction is an incredible one-shot midpoint set piece that has Rake and the kid car-racing through then running through the heavily populated Bangladesh slums with a SWAT TEAM, police, and a crazed fellow extractor in pursuit. It is unforgettable in its brutality, realism, creativity, and relentlessness. And that’s 100% directing.

There was one point in particular where they’re out on the street and there were probably 800 locals running around and I sat there wondering, are these all background actors? Or are they shooting in a real place and just allowing real people nearby? While that may sound ridiculous when you consider the legal ramifications of doing such a thing, the fact that I genuinely wasn’t sure is a testament to how realistic this sequence was. I don’t know too many directors who would’ve even have attempted it, much less pulled it off.

So does that mean there’s nothing action writers can do? Do we come up with yet another generic action premise and write lots of generic action set pieces and hope we’re that one script that gets picked out of the action slush pile to be made? Or is there something we can learn from these successful action films that goes beyond directing? That goes beyond Liam Neeson delivering the most famous challenge ever to a bad guy?

Here are four things action writers can do to improve their scripts.

The single best thing you can do is create a sympathetic main character. This is true for all movies. But it’s especially true for action movies because they don’t have a lot of character development. We’re never going to connect with a character in an action movie the way we’ll connect with one in a drama like, say, JoJo Rabbit, A Star is Born, or Marriage Story.

Dramas are built to explore the inner workings of people. Action, which is built to explore the external adventures of people, can’t compete with that on a character level.

However, a sympathetic main character can supersede depth when done well. When we feel sympathy for someone, we want them to succeed, regardless of how well we know them. The trick is, it has to be organic.

Liam Neeson in Taken is a great example. The thing that makes him sympathetic is that he was absent for most of his daughter’s life and now that he’s retired, he desperately wants to make up for that lost time. He wants to be a huge part of her life. That’s organic to the situation since the situation is about his daughter getting kidnapped.

If the writer instead would’ve had Liam Neeson recovering from alcoholism, going to AA meetings, and had him help another alcoholic in the group, sure, that is a sympathetic action. But what the hell does it have do with a movie about a former black ops agent whose daughter was kidnapped by international criminals? Make sure the sympathy is organic.

Tip number 2 might surprise you: Don’t turn your action movie into a character drama. If you read a lot of screenwriting websites, you’d think that the most important thing in writing action is creating characters with complex backstories and fully-fleshed out character arcs and tons of inner conflict. You certainly want some of that. But that’s not what action movies are for. They’re for action. Nobody leaves an action flick talking about the monologue where the hero remembers some valuable advice his mother gave him.

Aim to get the majority of your character stuff taken care of in the first act when you’re setting your hero up. Then have one or two ‘character reveals’ later in the script that provide more context to your character. Otherwise, keep your eyes on the prize and focus on the action. Cause when you try and make your action movie a character drama, you get Gemini Man. Nobody – and I mean nobody – wants Gemini Man.

Next is to put every creative atom in your body to work on creating strong original set pieces. It’s an action movie. If your action scenes are the same as action scenes we’ve seen before, we’ll get bored. And I don’t care how you get this across to the reader. If you have to tell them straight up, like Extraction that, “The next 20 page action scene will take place all in one take,” do it. Action is boring to read (“Bam bam. Pow. He ducks. He shoots. He punches”) so any trick you have up your sleeve, use it.

Creativity is essential when writing action. If you don’t have at least two set pieces that have never been seen before, don’t send your script out to anyone.

Finally, give us at least TWO unexpected plot beats somewhere in your movie. Like I said. Action is inherently boring to read. So you need to keep the reader on their toes. I was actually bored through the first 35 minutes of Extraction. It was all by the book. But the second Rake nears the extraction point and he realizes that something’s gone horribly wrong and they’re being ambushed, the movie turned a corner. I specifically remember sitting up after that moment and thinking, “Okay, we have a movie now.”

To help you, here’s a little saying you should have on repeat in your head: “Nothing should go according to plan.”

Straight action is always going to be the most generic genre. So you have to separate yourself from the pack somehow, despite the fact that your toolset is limited. Follow the advice above and you’ll come out on the other side better than most of your competition.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dueling Badasses – If it was just Rake going up against a bunch of faceless cops the whole movie, it would’ve lost a worth the stream [x] from me. What made it double worth the stream was this fellow badass who would keep catching up to Rake and battle him to near death every time.

What I learned 2: No excuses. Joe Russo – JOE RUSSO! – wrote this. Joe Russo is married. Joe Russo has two kids. Joe Russo was a director on two of the biggest movies ever made. Joe Russo just shot another movie this year with Tom Holland (Cherry). Joe Russo has started a production company with his brother where they’re trying to become the next Bad Robot. Yet Joe Russo still found time to write this script. No excuses, guys. No excuses.

I’m reposting this review because this project is now a go-movie with Ryan Reynolds and Shawn Levy, who just made Free Guy together. This is an OLLLLLD script that I never thought would see the inside of a movie theater. So today’s lesson – never give up!

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A 12 year old boy is visited by a mysterious man from the future, who claims he needs his help to save the world.

About: Paramount picked this script up exactly 1 year ago with Tom Cruise attached. It’s said that the script went for a hefty price (I’m guessing high six-figures). It’s stated on the script’s title page that this is a first draft. However, I have another draft of the script marked nine months earlier that’s listed as a “revised draft.” So maybe they started over? Were possibly released by one production company before moving to another? If I had the time to read both, I would, but I’m just going to go with the one that’s more recent. However, if it is an early draft, we should take that into consideration. Likely, more changes will come. Co-writer T.S. Nowlin wrote the upcoming sci-fi film “The Maze Runner,” as well as contributed to the new Fantastic Four reboot. Co-writing team Mark Levin and Jennifer Flackett wrote Journey To The Center Of The Earth and Wimbledon.

Writers: T.S. Nowlin and Mark Levin & Jennifer Flackett

Details: 10/9/2012 (First Draft)

SCRIPT SLUMP

I haven’t read anything that’s knocked me out in a long time. I’ve run into the occasional well-executed screenplay (solid structure, solid characters, good story), but this is what amateur writers seem to forget. The people reading your scripts aren’t interested in reading something solid. They’re looking for something great. They’re looking for something that stands out from the pack. Those are the only scripts that have a chance of doing anything in the industry.

This requires big ideas, taking chances that pay off, concepts we haven’t seen before, or if you do write a traditional story, executing the hell out of it. “Solid” might get you into meetings or land you low-level representation, but in order to stand out in this business, you have to blow people away. And it’s been a long time since I’ve been blown away.

So guys, stop being okay with “okay.” Push yourselves more. Tiger Woods didn’t become the best in the world by shooting for par. Neither should you.

Okay, now that I got that out of the way, let’s look at the curiously titled, Our Name Is Adam.

“Adam” introduces us to none other than… Adam! A 12 year-old boy who looks about 9. Adam is a runt of a kid with an asthma problem to boot. And to make matters worse, his 16 year-old brother Tommy is the Golden Boy, the kid who hits the home run at the end of the game and has the prettiest gal in school waiting for him at home plate.

But Adam’s life is about to get juicier. One night while home alone, he hears a noise in the shed, so he goes outside to check it out (a necessity in all movies – Must check out that noise!). There he meets a 30-something man in a space suit. The man eventually convinces Adam that he needs his help for a very special mission, and the two head off on a road trip across the country.

We learn that our pilot guy (spoiler) is actually Adam as an adult! And he’s come back from the future to destroy the program that allowed time travel in the first place. You see, his megalomaniac boss is using time travel to take over the world and this is the only way to stop him! A little complicated for a 12 year-old to understand, but after the pilot proves that he is, indeed, Adam as an adult, Young Adam is in.

Problems arise when OTHER pilots come back from the future to stop Adam and Adam. And we’re floored (spoiler) when we learn that the leader of these pilots is the adult version of Adam’s older brother, golden boy Tommy!

Adult Adam’s plan is a little complicated, but it amounts to finding the woman who discovered time travel and telling her not to share it with her business partner, the guy who eventually uses it for nefarious purposes. When Evil Company Leader finds out this happening, hell hath no fury. He will do everything in his power to take the Adams down!

Okay, before reading a new script, I try not to research the writers (I usually write the “About” section after I read the script). I don’t want their past works to influence my opinion. It’s kind of like when you’re jamming to a song only to later find out Katy Perry sings it. Had you known that at the time, you would’ve hated it. Your ignorance is what allows you to judge the song on its own merits.

So I didn’t find out until AFTERWARDS that this was written by the same writers who wrote Journey To The Center Of The Earth. Knowing these were the “Journey” writers actually made a lot of sense. “Our Name is Adam” has a light fluffy safe feel to it. Good if you’re a ten-year-old boy. Bad if you’re me. As I was looking for more.

Even with low expectations, though, the script still missed the mark. It’s just too surface level. Too easy. When writers make the argument that they’re writing for kids and therefore don’t need to add depth, I point them to none-other than Pixar, which makes films for kids as young as six years old which tackle themes like death and grief and abandonment – intense stuff – all the time. And kids turn out for those films in droves. So when I look at a script like “Our Name is Adam,” I feel gypped. There isn’t a lot depth here and it leads to an unsatisfying experience.

Let me give you a couple of examples of what I mean. First of all, I’m ALWAYS wary when I see a kid with an inhaler in a script. Not that it can’t work, but it usually implies a lack of imagination. Now an ADULT CHARACTER with an inhaler? That’d be different. By no means a mind-blowing idea. But it’d at least be unexpected. I mean how many times have we seen the meek kid with the inhaler? 500? 1000? So Adam having asthma didn’t instill a lot of confidence.

Then early in the script, Adam’s mom comes home to find Adam hanging out with a strange 35 year old man. She says, “Who is this?” He lies, “This is my science tutor. I paid for him with my allowance money.” She shrugs her shoulders and invites the man to dinner.

I’m sorry but WTFFFFFF???

IN what universe does a mother catch her kid sneaking around with a 35 year old man and invite that man over for dinner? There were a lot of little moments like this that kept me at arm’s length from the script.

With that said, the script DOES pick up in the second half once Adam and Adam go on their road trip, which shows that a powerful goal that keeps your protagonists moving can do a lot of the heavy lifting. Because up until that point, we’re just hanging out at this house with these guys and I don’t care what story you’re telling or how good of a writer you are. It’s hard to keep things interesting when your characters are hanging around in a house all day.

As you’re likely picking up on, this script wasn’t for me. So you’re probably asking, “Okay well Carson, you just said that we needed to write something great to break in. And then this sells for a million bucks and you don’t like it. What gives?” Well, the answer to that question is easy. Journey To The Center Of The Earth. That movie made money. And if there’s one universal truth in Hollywood, it’s that if you make money with a movie, Hollywood will buy up whatever you have next. Even if they don’t understand it. Even if they don’t like it. Because there are so few guarantees in this business that the only thing anybody has to go on is the past success of writers, directors and actors. If you have proven that your material makes money, Hollywood will continue to throw money at you, regardless of your rotten tomatoes score.

You the unsold amateur screenwriter, unfortunately, do not have that advantage. Therefore you must write something great in order to stand out. You might be one of the lucky ones to sell a mediocre script, but that will always be the exception and not the rule. And to bank on being the exception is the same as banking on the lottery.

Our Name Is Adam started slow, gained steam, but ultimately had too generic of an execution. With that said, I’d categorize “Journey To The Center Of The Earth” the same way. And that film made 240 million worldwide. So what do I know?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Take time to make the mundane story points in your script realistic. Cutting corners and going with schlocky reasoning always results in an un-engaging reading experience. The reason this happens is because writers are so focused on the complicated parts of their story, they de-prioritize the smaller stuff. The thing is, the smaller stuff still needs to make sense. When I see a mother casually invite Stranger Danger to dinner after he was sneaking around with her little boy, I’m jumping script. That isn’t believable on any level. It’s your job as a writer to make every situation believable, whether it’s a major plot point or a tiny one.

Yes.

I’m admitting it for all of you to hear.

I’m obsessed with 90 Day Fiancé.

But it’s actually worse than that. I’m obsessed with the spin-off of 90 Day Fiancé, called 90 Day Fiance: Happily Ever After?

For those who’ve never seen the show, it’s about people in America who fall in love with someone from another country, and they order something called the K-1 Visa which allows the foreign party to come to America for 90 days so both parties can get to know each other. And if they want to both stay in the United States, they have to get married. Otherwise, the foreign partner has to go back to their country forever.

The show works because it has a goal “to get married.” It has stakes. “If you don’t get married, you’ll never be together again.” And it has urgency. They have to figure out if they want to spend the rest of their lives together within 90 days.

The show also has a dark underbelly in that we’re constantly wondering whether the person coming to America is coming because they like the person, or is it to just get married in order to get American citizenship? Once they have the green card, will they disappear (and yes, many do).

The spinoff show that I’m binging (“Happily Ever After”) tracks these couples after they’ve gotten married. And here’s where today’s two screenwriting lessons kick in.

What I’ve noticed is that, from season to season, if your storyline doesn’t have THESE TWO ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS, they don’t let you come back. These components are 1) An active pursuit and 2) Conflict.

What does that mean, an active pursuit? That means that a person IS TRYING TO ACHIEVE SOMETHING. For example, take Russ, a vanilla Midwestern engineer, and Paola, a spicy Columbian. The two originally lived in Oklahoma. But Paola couldn’t stand it there. She had big dreams of being a model. So she demanded that the two move to Miami to pursue her modeling career.

This ensured, during the entire season, that the couple had an active pursuit. We want to watch because we want to see if Paola succeeds or fails at her venture. Conversely, what would’ve happened had they stayed in Oklahoma? Nothing. They wouldn’t be pursuing anything and, therefore, their everyday lives would be boring to watch.

The same principle applies to screenwriting. You want your characters going after something in their life. And it doesn’t have to be a job. In fact, in one of the greatest screenplays ever, American Beauty, Lester gets laid off. But he begins a pursuit to, for the first time in his life, do whatever the fuck he wants and be happy. Just like Paola’s modeling pursuit, Lester’s adventure is either going to end in success or failure and we want to stick around to find out which.

There is no American Beauty if Lester keeps his job and goes to work every day. Drama is about leaving the status quo behind and pursuing something bigger. If your narrative is sitting inside a big fat status quo sandbox, we’re going to be bored.

Let’s look at another couple, cute and smiley American, Loren, and tall and athletic Israeli, Alexi. In their first season, after having gotten married on the original show, they decided to have a second wedding in Israel for people who weren’t able to make it to the American wedding. The whole season felt forced but it gave the characters something to actively pursue. They had to plan this second wedding. Every episode had purpose because they had to plan plan plan.

However, in the following season, they didn’t have anything to pursue. There was a subplot of Loren doing some charity work but there was no big strong goal driving either of the characters. So what happened? They weren’t invited back for another season. That’s what happened.

It’s the same deal in screenwriting. If you don’t give your characters something big they’re pursuing, you don’t get to come back another season. I talked about this last week with Unorthodox. The main character didn’t just get to Germany and chill out. She began pursuing this music opportunity. If you don’t include that, your character isn’t going to have anything to do.

Has that ever happened to you? Where you don’t know what to write next? You have your hero but you have no idea what scene you’re going to write for them? If that’s happening, you haven’t given them an active pursuit. When you have an active pursuit, there is ALWAYS SOMETHING FOR YOUR CHARACTER TO DO. For example, if they’re trying to be a director, they first need to get a script, then they need to get a camera, but they don’t have money for a camera so they first have to make some money, then they need to location scout, then they need to cast people. A clear active pursuit will ensure that your hero always has something to do next.

The second thing you need is conflict. Active pursuits are great. But a pursuit is boring if everything goes smoothly. It’s the constant obstacles that create conflict which is what makes watching the pursuit fun.

Going back to Russ and Paola, Russ is super conservative whereas Paola is risqué. She wants to push the envelope with these sexy modeling shoots. Russ, meanwhile, is constantly telling her to pull back. She’s going too far. This push-pull conflict at the center of her pursuit is what drives the drama.

Now let’s be real here. This is surface-level reality show conflict. But the idea of what they’re doing is directly applicable to screenwriting. You always want conflict in your characters’ pursuit. Whatever the journey is, you need to make it as hard as possible for the characters to get there. Conflict is the tool that’s going to allow that.

In Loren and Alexi’s first season, there was some heavy conflict built around Loren ordering strippers for her bachelorette party. There were constant fights about that decision. Again, this is basic reality show fluff. But you can see how even basic reality show fluff conflict is better than no conflict. Cause in the following season, the two didn’t have any conflict with each other and they quickly became the most boring couple to watch.

When you’re writing, one thing that should constantly be on your mind is, how can I make this harder on my hero? Making things harder is what creates conflict. And you can make it harder with other characters. You can make it harder with unexpected developments (they lose the wedding venue the day before the wedding). Be creative. But whatever you do, don’t make it easy. Easy = boring = Alexi and Loren = not invited back for next season.

To wrap things up, I hope I’ve achieved two things. One, to introduce 90 Day Fiance to those who haven’t seen it. I’m warning you, you’re going to become obsessed so apply social distancing laws to your television. And two, the power of active pursuits and conflict in storytelling. Whether it’s a reality show, a TV drama, a short film, a snapchat story, or a feature screenplay, these two things are going to elevate your writing above the majority of writing out there. I promise you that! So get to writing. Or watching 90 Day Fiance – I’m okay with either.

Today, Scriptshadow asks… Is there a script in the last five years that’s this good that falls apart this spectacularly?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A couple and their adopted daughter have their cabin invaded by four strangers who take the family captive. But they’re not here to kill them. They’re here for something far worse.

About: This is a bestselling book that is now being made into a movie. The book was adapted by Steve Desmond and Michael Sherman, whose Back to the Future like script, “Harry’s All Night Hamburger’s,” finished top 10 on the 2018 Black List.

Writers: Steve Desmond and Michael Sherman (based on the novel by Paul Tremblay)

Details: 100 pages

This is going to be a controversial comments section. I implore you, once again, to read the script first and then read my review.

One look at the Amazon page for “Cabin” shows that it’s got 3 out of 5 stars on 790 ratings. That’s a low score for a book that has that many reads. Usually, if a book is popular enough to get that many purchases, it’s because people liked it and told other people about it, resulting in a higher score.

If you read the reviews, you get an idea of what the problem might be. Here’s a common response: “This is the first of his that I’ve read and although I liked his writing style and found the premise of the book fascinating, I (like many others) felt the tang of disappointment start to form about 2/3rds of the way through the book and then literally threw it on the floor after the final page. Had such great potential, but sadly fails to even remotely live up to itself.”

Yesterday we had a great script that solidified itself with a great ending.

Today we have a great script that destroys itself with a terrible ending.

In a way, a great script with a bad ending is worse than a bad script with a bad ending. Because at least with the bad script, you didn’t have any expectations. Conversely, being let down as badly as “Cabin” lets you down makes you want to “literally” throw the script “on the floor.”

So what’s all the fuss about?

7 year old Wen is outside a remote cabin catching grasshoppers when a giant of a man named Leonard blocks out the sun and introduces himself. Leonard appears to be a sweet man, befriending Wen and talking to her about her grasshopper catching adventures.

But there’s something underneath Leonard’s kindness, a kind of urgency that implies something bad is afoot. We see that badness in the form of his three approaching friends, a nurse, Sabrina, a short stocky cook named Adriane, and a redneck dude named Redmond. They all have homemade Mad Max like weapons with them.

Wen darts inside, telling her two dads, Andrew (liberal) and Eric (conservative) that there are bad people outside. The three of them try and fortify all entrances but Leonard kicks down the door. Once the invaders have cornered the family, they tell them they’re not here to hurt them.

You see, the four of them have been called here by a higher power shown to them through visions to get these three to sacrifice one member of their family. If they don’t do this by sundown, all 7 billion people on earth will die, leaving them to be the last three people on the planet.

Well, naturally, Eric and Andrew call b.s. Clearly you guys are all looney toons. But when the family refuses to kill someone, the invaders place Redmund down and beat him to death with their Mad Max weapons. Leonard then turns on the TV, where we see that a magnitude 9 quake just hit off the coast of Oregon. “This is just the beginning,” Leonard says. “The longer you wait, the more people die.”

Andrew calls the earthquake a coincidence but Eric is starting to waver. During the script, we occasionally flash back to the lives of each participant, both the family and the invaders, before this day happened. It helps provide some context for where each party is coming from. As sunset nears, Leonard does everything in his power to convince Eric and Andrew that this must be done. But they refuse to believe. Or at least Andrew does. Eric however………

This script FLEW.

One of the fastest reads of the year.

Right from the Ode to Frankenstein opening all the way til the death of the third invader, this thing moves like wildfire.

What I always tell you guys to do – no matter how much dead horse beating it involves – is to find a fresh angle on a familiar concept. Here, we have the very familiar setup of a home invasion. However, there’s a twist. The people invading the house cannot harm the family. The family can only harm itself.

At first glance, this doesn’t seem like that big of a change but the more you read and the more desperate the invaders become, you start to sympathize with their situation. What if you could only save yourself and everybody else on earth if you convinced someone to do the most horrible act a human can do? There’s a desperation to that situation because who’s going to willingly kill a family member just because you say the world’s going to end?

Another way that “Cabin” separates itself is the family involved. At first, I wasn’t on board with the choice of characters. Typically, in these types of scenarios, you’ll make the house owners entitled college kids. This means that you’re kind of rooting for the kids to kill each other. There’s definitely more of a “fun” vibe to the situation.

Whereas here, you have this progressive gay couple and this little girl… it definitely creates a more serious vibe. So I didn’t like that these were the people who were in this situation. It felt too intense.

But then I remembered one of the key tenets of good storytelling: Make things difficult. If we want the characters to die – like some Friday the 13th sequel – that’s not as gripping as if we want them to live.

With that said, I battled throughout the script with whether the execution was sophisticated enough to justify this choice. Had the ending worked, I’d say it was a win. But when the ending crashed and burned, it validated my fear. The writers didn’t have the weight to pull it off.

Despite that, the script is insanely readable.

I have to give it to these guys because they structured this well.

Normally, home invasions get boring in the second act because you’re artificially moving characters from room to room and recycling conversations to fill up pages. But, here, they add this repeating ticking time bomb of, if you don’t do the sacrifice, we have to kill one of our own. That means we’re always 12-15 pages away from another exciting situation. It isn’t just a way to keep your script entertaining. It’s a way to subconsciously create a structure in the reader’s head where they understand where the script is going and that they’ll be repeatedly rewarded for continuing to read.

This might sound like Carson psychobabble until you consider the opposite. Let’s say the bad guys don’t kill one of their own every couple of hours. Now you’ve got the same situation on page 90 as you had on page 10. Nothing is building. Nothing is getting worse. And most importantly, it’s hard to create new situations if everything stays exactly the same. There has to be consistent change in a script for it to remain interesting.

Let’s talk about that ending. Major spoilers ahead. You’ve been warned.

First off, the way one of the family members is killed is by accident. There’s a scuffle for a gun and Wen is accidentally shot and killed. There are a couple of things wrong with this. One, the audience doesn’t want a 7 year old girl to die in a movie that’s supernatural entertainment. They’d accept it if this was “Manchester by the Sea 2: Double Depression.” But this is entertainment here. So it feels off.

But also, it destroys the whole point of the movie – which is the choice. The invaders point out that Wen’s death wasn’t a chosen kill. Which means that Andrew or Eric still have to kill one or the other. But if you lose your 7 year old girl, that choice becomes a lot easier. Most parents, especially right after their kid died, would have no problem dying themselves because they can’t live without their child.

So as Eric and Andrew resist wanting to die, it doesn’t ring true. In fact, you wouldn’t even know they lost their daughter five pages ago.

But that’s not the worst part of the ending. The worst part is that Eric and Andrew hug each other, babble some nonsense about how love conquers all, then drive off into the sunset together, and we never find out what happens.

It was borderline infuriating. Look, I get that some writers like to leave the ending up to the reader. But the engine that drove this script was, is this thing real or isn’t it? And to not answer that question feels like a big F U.

Despite all this, I have to give the script a ‘worth the read’ because I absolutely loved everything up until Wen’s death. And that’s gotta be worth something, right? But I have a feeling this script is going to make a lot of people really angry.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In these types of movies, who you choose as the victims will determine the tone of the film. If you choose victims that the audience wants to see die (Friday the 13th), it will play as entertainment. If you choose victims that the audience wants to see live (Straw Dogs), it will play serious. Make sure you know which of these movies you’re writing and don’t mix them up!