You’ve been dreading it.

That word.

That evil enemy of all screenwriters.

The seven-letter word that may as well be the seven circles of Hell.

I’m talking about the…

Outline.

Look, I’m not going to debate you on whether it’s good to outline or not. For this script, you’re going to outline. And the good news is, it’s not going to be some elaborate ordeal. All you’re doing is taking everything that you’ve already written down and organizing it into a slightly more structured document.

A script is roughly 50 scenes. That’s assuming it’s 100 pages long with an average of 2 pages per scene. You might be writing longer scenes, like Quentin Tarantino does. That’s fine. You can easily calculate how many scenes you’ll write if your scenes average 5 pages per scene. 20 scenes.

The reason this is a nice number to know is that, now, when you lay out your outline, you can number the scenes and know how many scenes you’ve already imagined and how many you have left. Also, you’ll know where you’re missing scenes. You might have a bunch of scenes packed up in the first act and very few scenes after that. That should be an indication you need to add a few more scenes later on.

We want to make this outlining as simple as possible so here’s what I’d recommend doing. Divide it into four sections (First Act, Second Act A, Second Act B, Third Act). Each section will consist of 8-14 scenes depending on your writing style and the type of movie you’re writing. If you’re writing like Tarantino, closer to 8. If you’re writing like Michael Bay, closer to 14. Then, just start putting the scenes down chronologically and numbering them.

Since time is tight, all I care about is getting the bare essence down in the outline. But if you want to give yourself notes or write down some dialogue you had for the scene, by all means, go for it. You already have four scenes, since all of you did the checkpoints exercise. So put those in first. Then start filling in everything else.

By the way, I know that for some people, it’s confusing what constitutes a scene. If a couple is having an argument in their living room, then one of the characters storms upstairs, the other follows, and now they argue in the bedroom, does that constitute one scene or two? Generally speaking, if there’s a location change, it’s a new scene. But if the scenario naturally flows from one location to another, you can easily count it as one scene. Sometimes it’s up to the writer to decide. Kind of how it can be arbitrary where to break and start a new paragraph in a novel. I would constitute the above character argument as one scene. But if there was a small pause where both characters caught their breath in the middle, you could easily argue that it would be two scenes. The point is, don’t get too caught up in all that. What matters is we get as many scenes into the outline at possible.

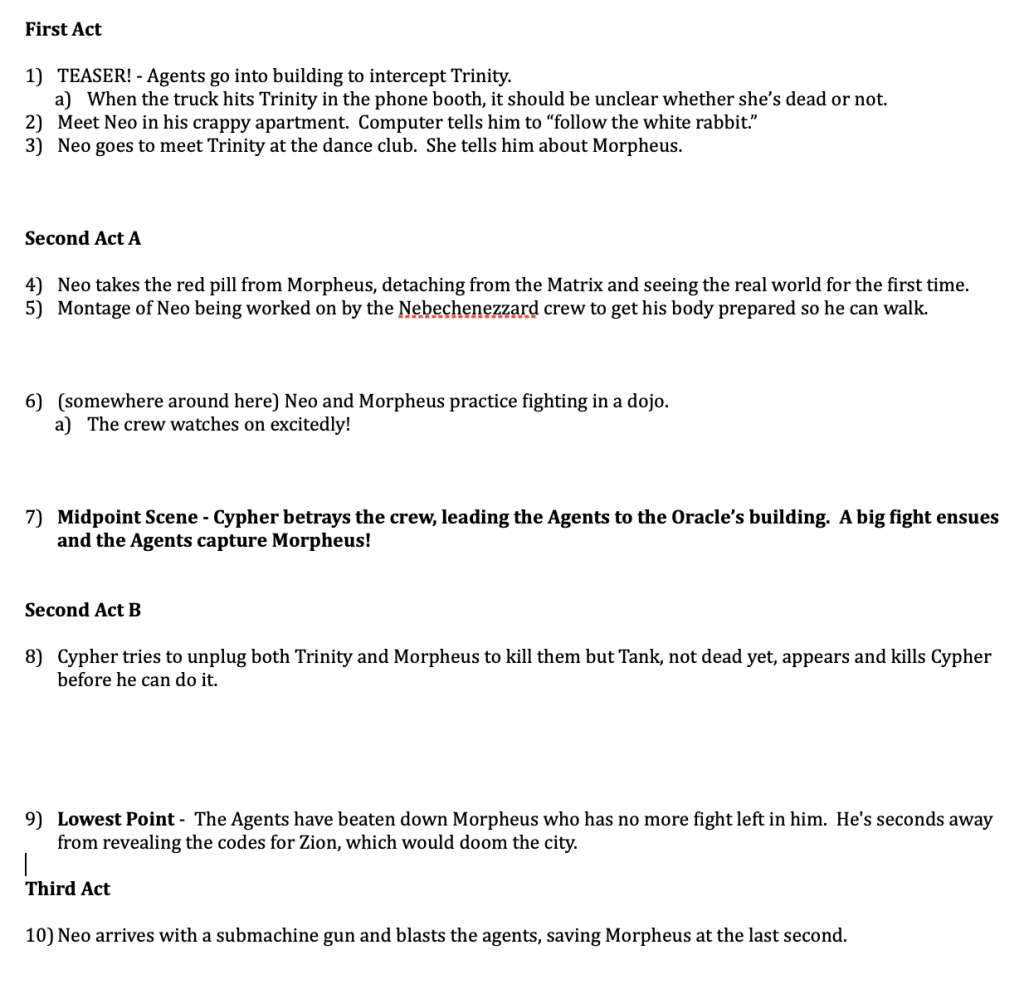

Here’s a general idea of what you should be going for…

As you can see, I’ve got 10 scenes figured out for a script I’m working on called “The Matrix.” Doing the math, that’s roughly 20-30 pages worth of scenes. Which gives me a good indication of how many more scenes/pages I need to get my full 100-110 page screenplay. Notice I’m leaving space between areas where I don’t know what’s going to happen yet. That’s so I have a visual indication of where I need to fill stuff in.

Just to be clear, don’t worry if you don’t have everything figured out yet. A big part of writing is discovering things along the way. So you’ll get new ideas as you’re writing Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, which will help you start filling in some of the thinner sections of your outline as you go. And, of course, if you don’t jive with this outlining method, feel free to use your own. Just remember that we’re all trying to do something different this time around to see if there’s a better approach than what we’ve been using in the past. So I encourage you to give this a shot.

Wow, six days later and we’re ready to start writing!

I’ll begin the official WRITE A SCREENPLAY IN 2 WEEKS posts Sunday night at 11pm Pacific time. That’s where I’ll tell you, specifically, how you’re going to approach this to easily finish a screenplay in two weeks.

Seeya then!

Okay, we’re just two days away from beginning our screenplay. I’m excited!

I’ve seen that some of you are concerned this is all going too fast. “Scripts need time and planning and research if they’re going to be any good!” you remind everyone.

Let me cut you off right there. The screenwriters who make the most money in this town are the ones who come in at the last second and rewrite a script in two weeks, or sometimes a few days, right before production.

Learning how to write quickly is going to help you in the long run.

One of things I became guilty of as I delved further into my screenwriting journey was over-prepping and over-developing my scripts. I would do everything you were supposed to do in screenwriting… EXCEPT WRITE.

If you have that problem as well, the only way to tackle it is to get outside of your comfort zone. And writing a script in 2 weeks is going to do that. Don’t listen to your brain. Listen to me. I will guide you to the good place.

Today’s task is a simple one. You’re going to FLESH OUT YOUR IDEA.

Carve out 2-3 hours, sit down, read what you’ve got so far with your title, your logline, your checkpoints, and your character essence sheet, and allow your mind to brainstorm. Any ideas you come up with, whether it be plot points, thematic ideas, what your supporting characters are going to do… write it all down in a single document.

This can be the same document as the one your checkpoints are in or it can be separate. Whatever makes you feel the most creative. We don’t want you stifled. We want ideas flowing freely. So if you think a blank document offers a better chance of that, go with the blank document.

The ultimate goal with today’s exercise is to fill in as much of the story as you can. The reason so many writers start screenplays that they’re unable to finish is that they don’t have enough of the story fleshed out in their head. They reach a point where they don’t know where to go next. Or they come upon a problem that they don’t have a solution for. The more ideas you put down into the document, the more prepared you are for those moments.

If you like more structure, divide your FLESHING OUT document into two halves. The first is notes to yourself and the second is things that will actually appear in the script. A note to yourself might look like: “Make sure every time Morpheus is mentioned in the early scenes, he sounds like a god-like figure.” A plot-related note would be, “Kylo is forced to fight the Knights of Ren in the desert just before he’s able to kill Rey.”

This should be fun! You’re exploring ideas. Coming up with a movie in your head. It’s the most exciting time of writing. Anything is possible! Writing only becomes a drag when we start judging ourselves. We’ll have plenty of time to judge in future rewrites. Today, though, is a celebration of your idea. It’s picking all the fruit off this amazing tree you’ve grown.

Tomorrow we outline.

Monday we write!

Note: The winner of the Sci-Fi Showdown Tournament will be reviewed on the Friday AFTER the 2 Week Screenplay Challenge

If you’re late to the party, we’re writing a screenplay in two weeks starting this Monday. Here are the previous links: Day 1 – Get ready. Day 2 – Pick a concept. Day 3 – Checkpoints.

California just closed down.

I know that’s freaking some of you out. But I’m a cup half full guy and the way I see it is THAT’S MORE TIME TO WRITE. All this time, the world seemed confused by the writer’s lifestyle. We’re introverted. We stay at home as much as possible. We get lost in a world we’ve created for hours at a time. Finally, our lifestyle has become an asset. This is what we do! Which is why the 2 Week Screenplay Challenge rages on.

Okay, we’ve got a LOT of work to do before we start Monday so let’s not waste any more time. Today we have TWO tasks. The first is to finish our final five checkpoints. If you don’t know what a checkpoint is, I explain it in yesterday’s article. My main concern is that you won’t be prepared for the second half of your screenplay. That’s the part that’s least shaped in your head and, for that reason, it’s where a lot of writers give up. They get to that post mid-point section and because they’ve thought so little about it, they feel lost and eventually lose confidence that they have enough story to finish.

So here are a couple of things to remember. An active protagonist will solve many of your plot problems because an active protagonist will need to pursue their goal/objective/solution. However, if your hero is less active, it can be hard to come up with ideas, since you have to come up with things that happen TO your hero as opposed to things your hero does TO the environment.

For example, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a tough movie to write because the characters aren’t pursuing any overt goal. They’re going about their day and reacting to the elements as they come in. Contrast that with something like, say, “I Am Legend,” where our protagonist, a doctor, is trying to come up with a cure. This ensures that he always has a goal, a task that must be accomplished. This allows for a lot more plot ideas.

So unless your story dictates a passive or reactive protagonist, I strongly recommend your hero be active. You’ll thank me later.

Okay now let’s talk about the second half of the movie in general. The second half of your second act (roughly pages 51-75 in a 100 page script) is the section of the script where things should be getting REALLY HARD for your hero. The obstacles will get much bigger than they were in the first half of the second act (in Invisible Man, our heroine gets thrown in a mental hospital). The things that are taken from your hero will be much more significant (the end of a relationship, the death of a friend).

What you’re trying to do with the second half of the second act is create a scenario under which success seems impossible for your hero. So whatever you can put in front of them, whatever you can take away from them, do it. This is the section where your hero is tested beyond anything they’ve ever endured before. Remember that that’s what all scripts are about – testing the characters – seeing if they’re strong enough to obtain the prize, whether it be mentally, physically, or (preferably) both.

If you want to watch a movie that exemplifies escalation throughout its second act, go rent Uncut Gems now. Every five minutes is more intense than the previous five minutes because the writers throw bigger and tougher issues at the hero.

Hopefully, that helps you come up with five more checkpoints.

Your second objective for today is to write down a 1-2 page “essence sheet” for your hero. I use the term “essence sheet” as opposed to “character biography” because I don’t want to know that daddy touched Jimmy when he was five. I’m more interested in how your character moves through the world today. What is their job? Are they married? What does their day-to-day life look like? What’s important to them? For some people peace and happiness is what’s important. For others, it’s having that pint of ice cream at the end of the day.

Of specific importance is the lens through which they approach life. I was just watching the Pauly Shore podcast with Adam Corolla and Pauly asked him if he was scared of getting the coronavirus. Corolla said, “I’m an Atheist, I’m either going to get it or I’m not, so in the meantime, I’m going to do whatever the hell I want.” That’s the perfect kind of thing to put in a character essence sheet. That sentence tells us so much about who Adam Corolla is. Try to find mantras like that that define your own hero.

And, finally, the most important thing of all is how you see your hero’s internal STARTING POINT and ENDING POINT in the movie. This is how your hero changes over the course of the story. Or, a better way to look at it may be, how the story changes your hero. In The Invisible Man, Cecilia starts off as a meek victim. Yet she ends up decisive and confident. In the film “Yesterday,” all our hero wants is to be famous. Then by the end of the story, he realizes that fame is a lot more complicated than he realized. Just like your plot has a starting point and an ending point that are different, your main character should have a starting point and ending point that are different.

You probably won’t ever want to look at this document again. Nor do you need to. Just the act of writing it is going to help you understand the character better. It also helps you understand what you need to establish early on in the script. You have to convey the essence of your character in those first few scenes. That then sets up how your character needs to transform by the end of the film.

Of course, there’s no law that states a character needs to arc in a story. But I find that trying to add a character arc is better than not trying to. If the arc doesn’t work, you can always eliminate it or downplay it in future drafts. But it’s hard to add a character transformation after the dye has been cast on the rest of the story.

So there we go. Five more checkpoints and a 1-2 page essence sheet for your hero. Get to it and I’ll be back tomorrow to help you outline!

You can find Day 1 of Prep here and Day 2 of Prep here.

When Stephen McFeely and Christopher Markus sat down to write the gigantic two-part Avengers finale, they admitted they were overwhelmed by the task. Filling up a six hour screenplay is a daunting experience. So how did they overcome the fear?

They started writing down CHECKPOINTS – major moments in the script.

For example, the scene where Captain America fights himself. They figured out, “Okay, we’re going to have that happen around page X in the story.” Once they were able to lay these checkpoints down on a timeline, they no longer had to write from page 1 to page 300. They only had to write to Page 25, when Tony Stark, Dr. Strange, and Spider-Man fight Thanos’s goons in New York City. And then to page 40, when the Guardians of the Galaxy rescue Thor.

Checkpoints give you smaller chunks of screenplay to conquer. The more of them you have, the smaller those gaps of blank pages become. All of a sudden the screenplay you’re writing doesn’t seem so big and scary anymore.

That’s tomorrow’s goal. I want you to come up with five checkpoints in your script. And then Friday’s goal is going to be to come up with five more, for a total of ten. I’m going to make it easy for you by providing you with the four most common checkpoints.

The first is the inciting incident, which tends to happen somewhere between page 5-12. Depending on your script, it could come sooner or later. All the inciting incident is is the introduction of the major problem your hero faces in the movie. So if it’s Avengers, it’s that Thanos is trying to get the Infinity Stones so he can snap away half the universe. If it’s John Wick, it’s when they kill his dog. If it’s Ad Astra, it’s when Brad Pitt is told his dad is still alive and missing and they need Mr. Pitt to find him.

Not all inciting incidents fall perfectly into the “major problem” category. For example, Uncut Gems. I’m not entirely sure what the inciting incident there is. Maybe it’s when Kevin Garnett won’t give him back the gem right away? Or is it when Sandler initially receives the gem? Not sure. Parasite as well. No real problem enters our poor family’s existence in the first act because the infiltration of the rich family’s home was the poor family’s idea to begin with. I suppose you could say that the inciting incident is when the family friend comes to the son of the poor family and tells him about the tutoring job.

In these cases, think of the inciting incident as any plot moment that jumpstarts the story. So Adam Sandler receiving the gem in the mail jumpstarts Uncut Gems. The son being alerted to the tutoring job jumpstarts Parasite.

The second checkpoint is the end of the first act, which is when your character commits to the journey. After the inciting incident, there is often a “refusal of the call” or a “delay in action.” But, eventually, our hero decides to go on the journey because there wouldn’t be a movie if he didn’t. This occurs around page 25-27 in a 100-110 page screenplay.

You see this in just about every Pixar and Disney movie. Most recently, Onward. Ian and Barley head off in search of their father. Inception when they head into Robert Fischer’s mind. Every Mission Impossible movie when they actually go off on the mission. This is where your movie officially begins.

Of course, just like the inciting incident, this doesn’t fit perfectly into every movie, particularly ones where the hero doesn’t go on a journey. Sometimes your hero is stuck in a house, like Michelle in Cloverfield Lane. If your script is non-traditional, look for something that approximates a first act turn. In Cloverfield Lane, for example, I might classify the first act turn as the moment Michelle DECIDES she’s going to try and get out of here. That switch in her demeanor from reactive to active signifies a new energy in the story.

Next we have the midpoint shift. Or the midpoint escalation. The best midpoint shifts transform the story. Make it feel different from the first half of the movie. You do this so your movie doesn’t have the same energy and feel the entire way through. Remember that predictability eventually equals boredom. So you want to use your midpoint shift to change things up a bit. A good example would be the midpoint shift of The Invisible Man. That happens when Cecilia gets booted out of her friend’s house and decides to prove this man is after her instead of allowing him to do what he was doing through the first half of the movie, which was torture her.

Or Parasite. That film had one of the most daring midpoint shifts I’ve ever seen, when they introduce a secret basement floor where a third family is hiding.

Finally we have the LOWEST POINT, which will take place at the end of your second act (between the pages of 78 and 90). Lowest Points are easy to come up with because it’s always some connection to death. Either literally or symbolically. It could be our hero’s friend died. If the main hero is a chef, maybe his restaurant closes down for good (dies). To use Invisible Man again, Cecilia is in a nut house, she’s tired of fighting, so she slits her wrists. In Parasite, it’s when the poor family’s house is flooded, destroying everything (their house literally dies).

So there you have it. Four checkpoints to get you started.

How do you come up with six more? That’s up to you. It could be one of the first scenes you imagined when you came up with your idea. Like the hilarious scene when all the human characters meet the game versions of each other in Jumanji. Or the convenience store scene in The Hunt. It could be something visual, like the famous giant piano playing scene in Big.

It may be a plot twist that happens, like the reveal of the girl in JoJo Rabbit. Or the surprise death of one of your characters. It could be a major monologue from one of the characters (Jules’ Big Kahuna burger monologue scene in Pulp Fiction) or a killer dialogue scene (DeNiro and Pacino in Heat) showdown. If you can envision it, it can be a checkpoint.

Some final thoughts. It’s important that you do this because we’re going to be making a mini-outline over the weekend and the more of these you have, the easier it will be to construct your outline.

Also, if you can, try and balance your checkpoints out so that you have roughly the same amount in the second half as you have the first. It’s easier to come up with first-half checkpoints because that part of the story is clearer in your head at the moment. But one of the big challenges of finishing a screenplay is that back half of the second act. It’s the section of the script we know the least about before we write. So if you can throw a couple of solid checkpoints in there, you’re going to be ahead of the game.

Now get to it!

Today is Day 2 of Prep to write a screenplay in 2 weeks. You can read the announcement for the 2 Week Screenplay Challenge here.

We’re five days away from FADE IN and we’ve got a ton of work to do. By this time tomorrow, you need to know what script you’re writing.

Yesterday, I told you to prepare 5 loglines for scripts you want to write. Then, either e-mail five friends of yours and ask them to rank the ideas from best to worst. Or post the loglines right here in the comment section and have the Scriptshadow community rank them for you. Whatever gets the most votes, I’d suggest you write that idea.

If you want my personal opinion, my logline service is still cheap. $25 for a rating, a 150 word analysis, and a logline rewrite. I will reintroduce the 5 loglines for $75 deal through the weekend. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested.

Like I said yesterday, committing to an idea will be the most important decision you make in this challenge by far. Good ideas inspire exciting stories. Weak ideas are like swimming with cinder blocks tied to your feet. Every scene is a chore. Finding the next plot beat is akin to finding toilet paper at the supermarket.

How do we define a good idea versus a bad one? While it may seem like how good an idea is is in the eye of the beholder, there are things you can do to improve an idea’s potency. A good idea is one that does a lot of the writing for you. Common factors include a strong main character goal, a heavy dose of conflict in the way of your hero’s journey, and the stakes feel big. That’s important – that this story feel like major consequences are involved. If you want to add even more charge to the idea, contain the time frame. Create a sense of urgency (the goal must be achieved soon or else…).

I would also like to introduce a new concept that has a major effect on how appealing your idea is to others. It’s called CREATIVE POTENTIAL and you want your ideas to have it. Sure, you can put a John Wick like character in your lead role and say he has to kill the evil bad guy within 28 hours or his family will be executed. That hits all the beats I mentioned above. But with zero creativity behind the setup, it doesn’t leave a lot of openings to give the story anything people haven’t seen before. Nor does it offer opportunities for surprising plot revelations. It’s a bland straightforward idea that lacks anything to distinguish it from the pack.

So what’s a good idea that contains all these things?

Jurassic Park, duh. I know it’s an oldie, but it’s a goodie. A group of people gets stuck on an island of dinosaurs. Goal = escape. Stakes = their lives. Urgency = they’re being chased so they have to achieve the goal NOW. Conflict = dinosaurs are trying to kill them. Creative Potential = a freaking island of dinosaurs. There are so many fun creative plot things you can do with this setup.

Okay, what about a bad idea? An idea that doesn’t “write itself.”

I’m going to say Marriage Story. I know I just used that as an example yesterday of an easy script to write but now I’m having second thoughts. The idea doesn’t have a goal. It doesn’t have any stakes really. The damage to this couple is already done at the start of the story. The narrative is used to get us to the legal finish line of the divorce. There’s clearly no urgency here. The script’s sole dramatic engine is the conflict between the central characters, which admittedly works well. But because you don’t have any real goal pushing the narrative, coming up with scene ideas for this must have been a nightmare. It’s always easy to see how they got there in the rear-view mirror, but I suspect there were a lot of long nights of Noah Baumbach staring at the blank page not knowing what to write next. Goal-less characters are responsible for driving many a writer insane.

And here’s another good idea…

This one a longtime Scriptshadow reader alerted me to from a previous contest – “It’s Christmas time in Berlin, 1944. A serial murderer is on the loose, and a confounded police detective springs a famed Jewish psychologist from Auschwitz to help him profile and catch the killer.” – The script would go on to sell to Fox. We’ve got our goal – catch the killer. We’ve got stakes – people are dying. We’ve got urgency – the longer it takes to catch him, the more people die. We’ve got some great conflict at the center of the story – A German police officer and a Jewish psychologist working together during one of the most tense times in history. And the creative potential of this idea is off the charts. You know you have a good idea when anybody who reads it can start thinking up fun scenes to write.

Finally, here’s one of Magga’s loglines from yesterday, which I had issues with. I hope Magga is okay with me critiquing it because your other idea, Shalloween, sounds great.

LIVE FOREVER – At the height of the britpop craze, demand for the Oasis live experience was so high that several cover bands got national reputations in England. This is the story of a fictional one.

Where is the goal in this idea? I suppose it’s for this fictional cover band to perform live? Okay. I guess that’s not terrible. But if I have to dig to understand the goal, then I don’t know what the stakes are. I can’t find the urgency. I’m not seeing any conflict in this logline, which gives me no sense of what the second act is going to be about. It also feels weird that the first half of this idea is about a real time and real people and the second half introduces a fictional element. Who cares if some fictional Oasis cover band gets to play live? This would be so so so much better if this was a true story.

But look, don’t feel bad if your idea isn’t loved. Picking ideas is an inexact science. The reasons we fall in love with an idea don’t always match up with how the rest of the world perceives them. Our hero may remind us of a fresh take on our favorite movie character of all time, “John Smith” from the movie “Takedown.” Meanwhile, everybody else just sees a generic straight-to-video action thriller. This logic can be applied to Live Forever. Magga may love Oasis and that’s why they’re passionate about writing a movie about them. But all we see is a confused story with a weak narrative.

That’s why I want you to share five movie ideas instead of one. At the very least, you’ll be working with an idea that beat out four others. So, if you want to participate, post your five movie ideas below in the comment sections. Please include titles and genres.

You must pick a movie idea by tomorrow because tomorrow we have to start prepping to write the script. We only have five days for prep. So let’s get to it!