I have one question for you before I get to today’s article. Is the key to getting an original script turned into a wide release movie one single shot? I know it’s a small sample size but after 1917 made a shocking 36 million this weekend (when was the last time a World War 1 movie made 36 million in a weekend???), we have to ask the question. Cause there was that OTHER original idea – a little movie called Gravity – that was a single-shot film (for the most part) and that became a surprise hit also. Coincidence?

I’m asking the question half-jokingly but it’s an intriguing discussion. It’s so hard to get any original movie released these days. So if you can find any trend out there, you run with it. Now both these movies were writer directors. But I think a spec writer could do an even better job because they wouldn’t be worried about pulling off certain shots and whether something would be too difficult or not. They could write whatever came to mind.

Why does the single shot movie work? Well, obviously, it’s hard to pull off so it’s easy to build buzz around a one-shot movie. But from a screenwriting perspective, if you’re doing something in one shot, you have to create a sense of urgency or else there’ll be a bunch of slow spots in the movie. So, in a way, it forces you to create a really tight exciting story. Might we now get a few single-shot spec scripts in The Last Great Screenwriting Contest? Maybe a single shot social horror thriller even? We’ll see!

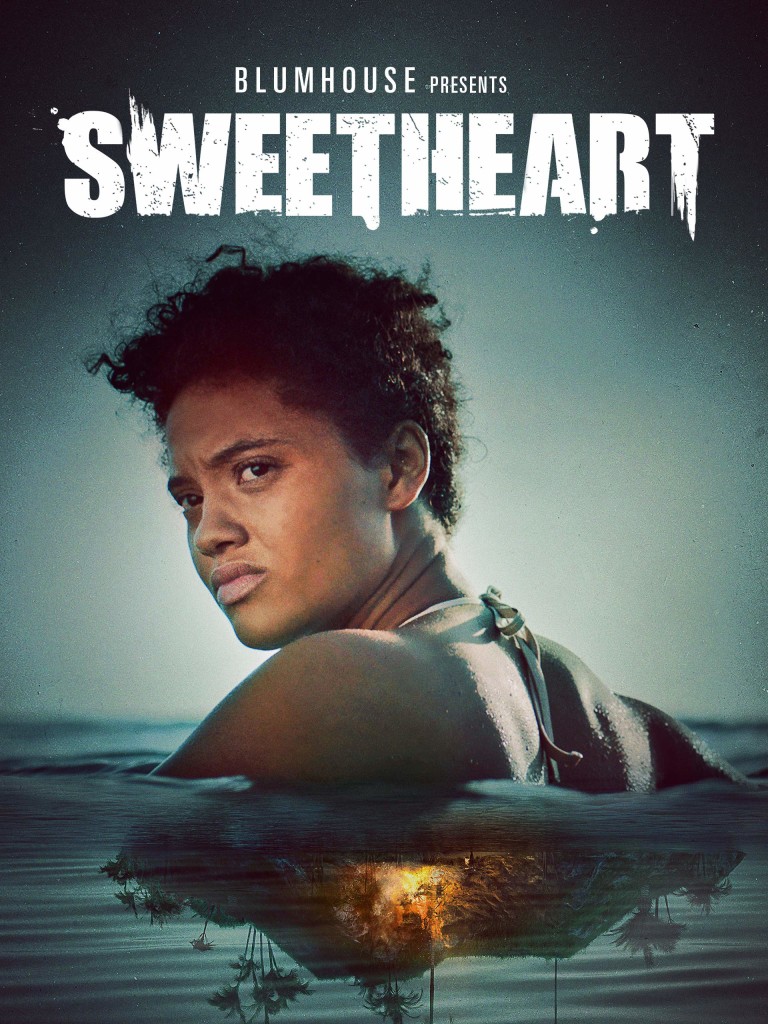

Moving on, I’m going to talk about producing today because that’s where my mind is at. This past week, I stumbled onto a movie called “Sweetheart” on Netflix. The film is about a shipwrecked girl who wakes up on an island only to learn that a monster lives on it as well. The movie follows her journey both trying to survive on an island and trying not to get killed by this monster.

The main reason I watched this movie is because it’s a movie I would’ve made. You’ve got a contained thriller. You’ve got a supernatural threat. That combination has been responsible for a lot of movies that have made a lot of money. You’ve also got a hot young director coming off a hit movie at Sundance. I would’ve seen all these elements and thought, “Slam dunk.”

Unfortunately, as I hit the 30 minute mark of the movie, I was struggling to stay invested. I kept asking myself, “Why? This is a movie you would make. Why isn’t it working!?” As if being able to answer the question would ensure that every future movie I made wouldn’t suffer the same fate. Gradually, after I was able to take my emotion out of it, I realized it came back to script problems. More specifically, it reminded me that contained thrillers are incredibly hard to pull off. And Sweetheart shows you why.

When we come with a contained idea, the first thing we think about is the cool moments. For example, in the big spec contained thriller, “Shut In,” you would think of the moment where the main character nailed the bad guy’s hand into the floor to keep him there. Or, with this movie, you might imagine the first time our heroine sees the monster. These moments are the moments that get us excited to write a script.

Here’s the problem though. There are only about four of five of these big exciting moments in your head when you’re putting an idea together. In the best case scenario, these moments take up fifteen minutes of screen time. In addition to this, you’re likely going to have a big climax, so we can add another 10-15 minutes of screen time on top of that. This means you have 30 minutes figured out. Which means you still have 70 MORE MINUTES TO FILL.

Now filling up 70 minutes in a Star Wars or James Bond movie isn’t that difficult. You just go to a new planet or a new country and throw in a car chase. But 70 minutes in a CONTAINED THRILLER??? Even screenwriting aces have trouble making those minutes interesting. Usually, all you have is a few characters and a small space. What do you do with 70 minutes of that?

That’s clearly where Sweetheart fell apart. It didn’t have a plan for those 70 minutes. It made the fatal mistake of assuming the concept alone was going to do the work for it. That we’d be so excited in the moments between the monster attacks to see it again that we’d wait through anything. Watching a character washed up on an island try to survive on page 10 is interesting. Not so much on page 60, when we’re bored of it.

It’s the writer’s job, then, to come up with plot beats that keep the story moving. And, to their credit, they try. For example, a couple of other shipwrecked characters (from her ship) show up about 50 minutes in. And that, at least, gives us some new scenarios, like characters being able to have a conversation. However, the plot beats were lazy. In fact, there’s another girl washed up on a deserted island with a monster spec that was written at the same time as Sweetheart. What happens at the 50 page mark of that script? A couple of shipwrecked characters show up. In other words, your story choice was so predictable that the only other person writing this idea came up with the same plot beat.

It is IMPERATIVE as a screenwriter to always check yourself on these things. When you come up with a plot development, one of the first things you should ask yourself is, “Would someone else come up with this as well?” And if the answer is yes, don’t write it. Come up with something else. The counter-argument to this is, “Well how many plot options are there in this scenario? Bringing in new characters is one of the only things you can do.” There’s never a situation where there’s only one thing to do. There are always options. It’s definitely harder to come up with the options that nobody’s thought of yet. But those are the ones that are going to make your script great.

Another issue was that there was no sense of danger in a script about a woman stuck on an island with a monster. She and the monster routinely see each other and nothing happens. She’s easily able to hide under a log or behind a tree. It gets to the point where you’re wondering if the monster is even interested in killing her. If the only person in your thriller script isn’t in danger, you don’t have a thriller.

In retrospect, I think I know why they did this. If the monster is too aggressive and powerful, the movie’s over in five minutes. The only way to make the movie last was to make him passive. But then where’s the movie? The last time I checked, the alien in “Alien” doesn’t occasionally walk by the characters, uninterested in them. It aggressively hunts them down one by one. And I’m not bashing Sweetheart for not living up to the greatest sci-fi horror film ever. I get that these are tough script problems to figure out. But if the audience isn’t feeling fear for your hero, we don’t have anything to work with.

I bring this up in the hopes that those of you writing contained thrillers for The Last Great Screenwriting Contest approach these dangerous 70 minutes strategically. You might want to watch Sweetheart and read Shut In back-to-back. In Shut In, we have two children in danger outside the room our hero is stuck in the entire movie. That alone adds a sense of urgency and tension that Sweetheart never had. It ensured that we were always rooting for our hero to escape the room so she could rescue her kids.

And that’s probably the best lesson to learn for a contained thriller – personal character-driven stories give you the best chance at surviving those big gaps of screen time where you don’t have a set-piece. I’m still on the edge of my seat for the Shut In heroine when all the noise died down because I still want her to save her kids. I’m not scared for the Sweetheart heroine at all because, from what I can tell, this monster isn’t interested in killing her.

Did you guys see Sweetheart? If so, what did you think?

First off, I want to thank everyone who’s congratulated me both in the comments section and personally. The response has been overwhelming and one of the themes I’ve spotted in the aftermath of my producing announcement is that people respect when you follow your dreams.

It’s easy to accept that comfortable safe route in life. And there’s nothing wrong with it. Especially if you have a family you’re supporting and lots of responsibilities. But I didn’t have that excuse and my life was definitely missing something. After a lot of introspection, I realized that what was missing was doing something I really wanted to do. Even if it scared me. Fear is a strong deterrent but the reality is, fear is where all the fun is. That’s where the best things in life happen, when you do the stuff that scares you. If that inspires any of you to make changes in your own life, great. Even after one week, I can confirm that it’s a lot more exciting on this side of the curtain.

Moving on to today’s showdown, I didn’t get that huge glut of final day submissions I usually do before a showdown. But I did get a lot of contained thriller submissions for The Last Great Screenwriting Contest. So I think what a lot of people did was shift their Contained Thriller script over to the big contest. Which I understand. In a Showdown, you’re not guaranteed I’ll read any of your script, whereas with the contest, you know I’ll read at least the first 10 pages. I’m not sure what this means for future showdowns but we’ll figure it out.

In the meantime, I’m hoping that one of these five scripts is awesome and we’ll have found our first big producible script of the year.

For those new to the site, Amateur Showdown is a bi-weekly tournament where I pick five screenplays that were submitted to me. Then you, the readers of this site, read as much of each script as possible and vote for your favorite in the comments section. The winner will receive a review the following Friday that could result in props from your peers, representation, a spot on one of the big end-of-the-year screenwriting lists, a partnership with yours truly, and in rare cases, a SALE!

In order to participate, e-mail me at carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Include your script title, the genre, a logline, and a pitch to myself and potential readers why you believe your script deserves a shot. It could be long, short, passionate, to-the-point. Whatever you think will convince someone your script is worth opening, make your case. Just like Hollywood, the Scriptshadow readers are a fickle bunch. So be convincing!

Good luck to all the writers this week!

Title: Deathbed

Genre: Contained thriller/horror

Logline: A young nurse must fight for her life when the bed she ordered for a back injury turns out to be haunted by the victims of a serial killer.

Why you should read: When Carson announced the contained thriller/horror AOW I was super stoked. I’ve been a fan of the genre ever since I saw Buried. Coming up with an entertaining feature length script with a single location and minimal cast is arguably the toughest writing challenge of all. Deathbed is my attempt. It takes a big risk in that it attempts to combine two sub-genres: Supernatural with Home Invasion. I hope you enjoy it!

Title: Hunny Pig

Genre: Contained Thriller / Dark Comedy

Logline: A recreational poker player, unemployed, abandoned by his family, and desperate for a big win, is slowly driven to the brink of madness by an unbeatable online nemesis who may be Satan himself.

Why You Should Read: Sometimes we write trying to fix the things that are broken in our lives. Well, on-line poker nearly broke me. The drug I never knew I needed became the thing I couldn’t live without. It took hold of me in ways that cocaine or alcohol never could. With a career in free-fall and cursed with endless free time, I would play long into the night, burning through cash and literally SCREAMING into the cyber-void, unable to cope with my constant losses. The more I lost, the angrier I got. It became so bad, my wife threatened to leave me.

Luckily, salvation came from an unlikely source; the US Justice Department — who shut down legal on-line play in 2011. And although I reclaimed my sanity and patched things up with my wife, I never forgot how that crack in time made me feel: UNLUCKY. WORTHLESS. CURSED.

Years passed, and I thought — why waste all those juicy negative feelings? Turn them into a ultra-low-budget, darkly comic screenplay instead! So I did! I hope you enjoy… HUNNY PIG.

Title: The Album

Genre: Contained thriller

Logline: After being kidnapped by a psychotic music producer, a guitarist and her drummer boyfriend are forced to record an album in chains while they try to escape his studio prison.

Why you should read: We were shooting for Misery meets Green Room. Would love to see what the people here at SS think. It’s a quick read too at 85 pages.

Title: In The Night Garden

Genre: Psychological Horror

Logline: After a pregnant sleepwalker kills her husband and daughter, she is transferred to a mysterious facility for treatment, only to suspect the overseers are after her unborn child.

Why You Should Read: Can a conversation be terrifying? The psychological horror genre has always fascinated me, and for years I tried to pursue it, only to fall back into cheap tropes: jumps, gore, monsters, and haunted-house scares. And while I can’t promise that this screenplay avoids these completely, the core of its horror runs far deeper. The unholy lovechild of Ex Machina and Rosemary’s Baby, In The Night Garden explores motherhood in ways that will shock, disturb, and stay with you long after the final page has turned.

Title: The Fire Tower

Genre: Contained Thriller

Logline: When a family on vacation to a remote fire lookout tower rescues an injured female hitchhiker, they wind up in a battle for their lives.

Why You Should Read: When I was 10, we went on a cross-country camping trip out west. One night we got horribly lost on a winding road, high in the mountains. Out of the darkness a hitchhiker jumped in front of our car asking for a lift. We gave her some water and snacks (but my mom wouldn’t let my dad give her a ride). Later, I was told that a whole family had disappeared without a trace not far from there. That was the seed of the story. But I needed a contained space to trap my family.

Lookout towers have been used in the United States for 100 years. At the peak of their popularity in the ‘40s, the U.S. had about 8,000. Today, there remain about 85 fire lookout towers in the U.S. in extremely remote mountain areas in the National Forests which you can rent for $25-$75 a night.

As those of you who saw my beginning of the week post know, Scriptshadow is holding one last giant screenplay contest, and it’s going to be competitive. I expect tons of entries. Especially since it’s FREE. So how do you write something that’ll stand out from all the other entries? Well, unlike a lot of contests out there, you know the person reading your script. Me. And therefore, all you need to do is go back through my review history to see what kinds of scripts I like and what kinds of scripts I detest. For example, if you’re writing a biopic, this contest isn’t for you. And if you’re writing a music biopic, you’re actively trying to make me hate your screenplay.

My first piece of advice is NAIL THE FIRST 10 PAGES. In case you didn’t read, I’m only promising to read the first 10 pages of every entry. If your scripts doesn’t interest me by then, I will not continue reading. What I personally look for in the first ten pages is: Can the writer tell a story? Are they giving me a scene or a sequence that has its own beginning, middle, and end? Like a little mini movie. You hook me on that first page so I have to keep reading to find out what happens next. The opening scene in Scream is a good example. Opening scene in Inglorious Basterds. Raiders of the Lost Ark. If your script isn’t the kind of script that works with a full-on mini-story at the beginning, make sure you have another plan to hook me in those first 10 pages.

As for the actual scripts, I’m going to be the most excited about high concept reasonably budgeted ideas that can be made for under 5 million dollars. Horror, sci-fi, contained thriller – the kind of stuff that can be easily marketed. As cliche as it sounds, if you can’t envision the poster, it’s probably not marketable. If you can’t envision a trailer that would make everyone want to see the movie right away, it’s probably not that great of an idea. Try to imagine you’re in my position. You’ve got a small production company. You want to make a big splash with your first film. But nobody’s going to give you a lot of money when you’re just starting out. What kind of project would you commission under those circumstances? And, by the way, that’s how 80% of the production houses in Los Angeles work. So this is a good approach to have regardless of if you’re entering my contest or not.

Also, I would avoid genres and story-types that are highly unmarketable, even if you’re a good writer. In my last contest, the winner was “The Savage.” Here’s the logline – “The incredible true story behind one of America’s founding myths. After being kidnapped from his lands as a child, the Patuxet Indian Squanto spends his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that changes the course of history.” The writing was great. The research was strong. The script had a lot of good moments. It was better than any other script in the contest, hands down. However, when I went to pitch it to people, everyone’s eyes glazed over. You have to see it from the producer’s or financier’s point of view. The only way a movie like this can exist is if it gets one of the top 10 directors in the world and a studio puts 75 million dollars behind it and another 50 million down for an Oscar campaign. Everyone in town knows that’s a pipe dream scenario. It can be done. But the odds are so astronomically small that nobody wants to take the chance. Not when the next John Wick is out there. Or, if they’re looking for an Oscar, they’re going to grab a drama that costs 25 million or 40 million. Not 75-85 million. So keep that in mind if you’re thinking of writing about the birth of the Ottoman Empire.

If you’re not a high concept person, you need to have a unique voice. The way you view the world needs to be unique. Your writing style needs to be unique. Your sense of humor needs to be unique. Essentially YOUR VOICE BECOMES THE HOOK. Nightcrawler, Birdman, American Beauty, Three Billboards, The Big Lebowski, Daddio. A couple of these scripts are scripts I didn’t connect with when I first read them but it was clear the writers had a unique voice. And when all concepts fail, agents, managers, producers, studios, will gravitate towards the writer who doesn’t sound like everyone else. And, by the way, that doesn’t mean copying your favorite writer with a unique voice. Doing your version of Quentin Tarantino is just going to make you a not-as-good Quentin Tarantino. The trick with voice is that it truly is YOUR voice. I would stay away from trying to write one of these scripts unless you’ve been told by people that you have a unique way of seeing the world and writing about it.

Another good strategy to employ is to find old successful movies that people have forgotten about and give them a fresh new horror or sci-fi twist. That’s what Get Out was. It was, “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner” with a horror twist. Star Wars was a western set in space. San Andreas is an update of “Earthquake.” People in Hollywood have a 5 year memory. So you can find all sorts of gold in old movie concepts.

Selfishly, I want to make the 2020 version of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off as well as Back to the Future. I want to bring back the 90s spec craze. I want the next Seven, Basic Instinct, The Sixth Sense, Scream. I also want to bring back high-concept big-budget original concepts, like The Matrix. Like everyone in the business, I’d like to find the next Ghostbusters or Goonies. Just remember, the higher the budget, the better the script has to be. With lower budget scripts, I may overlook problems on a good concept because I know I can help the writer fix them. But with these big-budget scripts, it’s not worth it for me to spend three years with a writer trying to get it in just the right shape so that MAYBE a studio makes it their ONE original big-budget movie that year. An example of a good big-budget script I’d take a chance on is The Traveler.

And finally, some miscellaneous thoughts. Social thrillers (Get Out, Get Home Safe, The Hunt) are hot. But everyone is writing them. So you better have a good idea. Horror always sells. I would love to start a horror franchise. I’m open to all horror sub-genres. I’m keen on finding a new twist for the zombie genre. I have a few ideas myself but maybe you have one that’s better. I’m obsessed with sci-fi so I would love to find the next Inception, Source Code, or The Martian. I absolutely LOVE plane disaster or plane in danger concepts. One of my goals is to make the best plane movie ever. New technology is one of the last frontiers for new ideas. You want to be the guy who writes “Stuber” two months after Uber becomes a phenomenon. If you’re a TV writer, I’m open to anything, comedy or drama, but my favorite show ever is Lost. I want to bring that mythology and that high-concept feel to a show in 2020. My other favorite TV shows are The Office, Fargo, Modern Family, Fleabag (a show PURELY BASED ON VOICE!), Succession, Breaking Bad, The Good Wife, Barry, and Community.

And if all else fails, just go with simple story and a complex main character. Rocky, Joker, Nightcrawler, Psycho, Terminator, Source Code.

You now know the blueprint for winning your reader over. What are you waiting for?? You only have until June 15 to write your script. GET STARTED!

Genre: Action

Premise: When a talented hacker is recruited by the mysterious Cicada 3301, she gets wrapped up in a plot that threatens to destroy the entire world. Based on the real organization.

About: This script finished number 4 on the 2019 Black List. The writer of the script, Lillian Yu, made last year’s Hit List with her script, Singles Day.

Writer: Lillian Yu

Details: 108 pages

One of the reasons it’s so hard to make hacker movies work is because there aren’t a lot of ways to make typing on a computer interesting. Even with the fancy graphics, it’s a bit like chronicling the life of a famous writer. The act of writing is boring to watch, just as the act of hacking is boring to watch. I found this out the hard way a long time ago when I wrote a hacker script. No matter how cool I tried to make the hacking process, it always came back to my hero sitting in front of a screen pounding buttons. I could never figure it out.

The more interesting approach is probably to have your hero be operating in the real world and your villain be the one who’s the hacker. That way, they’re controlling the elements around you and you have to constantly adjust. I think The Net, with Sandra Bullock, took this approach. Enemy of the State as well. And probably some recent movies that I’m forgetting. So how does Yu solve this problem? Let’s find out.

Jane is a computer genius, so much so that she got a full-ride to Harvard. Jane is also a bit of a social justice warrior, and when she tries to expose one of Harvard’s premiere fraternities for covering up sexual assault, she finds out that Harvard is more interested in keeping up its pristine image than being Ronan Farrow’s next expose. So Jane is kicked out of school.

She eventually gets a crappy job at an insurance company where she secretly retroactively adjusts policies so that poor people don’t get screwed over. This catches the eye of a secret organization known as Cicada who recruits Jane to be a member. She’s flown to Paris via a remotely controlled airplane, passes a bunch of a tests, then meets the team, which is basically a techno-savvy version of the Mission Impossible group.

The leader, Adam, explains that Cicada is an organization whose sole job is to do right in the world. For example, there’s a guy running a Ponzi scheme 10x worse than Madoff. Cicada digitally transfers all that money back to its rightful owners. All in the background.

The problem is there’s another organization called Zero whose mission is the same as Cicada’s. To save the world. Except their business plan has gone awry recently and their current plan is to infuse North Korea with trillions of dollars so it can launch a nuclear war against the world. All of this is happening at the end of the month, so they need to act now.

There’s a major gathering of the most influential people in the world at a castle and the head of Zero is going to be there. They need to get there and kill the guy. Unfortunately, hacking isn’t going to be enough to do the job. So Jane must go through action training to get her up to speed in hand to hand combat and shooting peeps in the face. She barely passes and off they go.

Everything at the castle goes cleanly at first, but then Jane runs into a Zero member, who informs her that Cicada is lying to her. That she was recruited specifically to be the fall guy when all of this hits the press. Unsure of who to believe, Jane must decide who to align herself with, the company who recruited her, or the apparent enemy.

One of the best ways to convey a script read is to take people inside the mind of the reader as they were reading. Which is what I’m going to do here. The first thing I noticed about this script was that the writing was strong. There was a vibrancy and energy to it that was exciting. The description, in particular, was a cut above what I usually see.

So I was excited. However, I then ran into my first issue with the script. The main character was really angry at the world. And angry main characters rarely work. It’s hard to root for them, plain and simple. Whenever you’re unsure of what you can get away with with your main character, just imagine them in real life. Do you like angry people in real life? I don’t. Most people don’t. So that’s probably not going to work as a main character. It can work with a side character since they don’t need our emotional investment. But it’s a major risk when you’re doing it with the hero.

I think Yu sensed this and, therefore, gave Jane a couple of save the cat moments. Her mom dies. And she helps a wronged insurance customer get their money back. This can sometimes work to balance the character out. But only if the implementation is invisible. I saw these moments for what they were – attempts to get us to like the character. Once we see the hand of the writer writing, we know we’re being manipulated.

Regarding the problem I brought up in the intro, Yu made the wise decision to train Jane in more than computer hacking. She’s taught how to kill and fight and drive which allows her to get into more interesting situations in the big set pieces. The issue there was that it wasn’t believable. She’s trained to be an action star in a week.

This is a common problem in these “ordinary hero thrust into extraordinary situation” movies and writers have developed all sorts of tricks to make the leap passable. For example, in the movie Wanted, didn’t James McAvoy’s character have a father who was special and therefore he’d inherited special abilities as well? He just needed someone to open them up?

To this day, the best movie that’s ever done this is The Matrix. It was instantly believable that a nobody who doesn’t know how to fight could fight like a master since when you’re in a computer system, any skill can be uploaded into you. It’s one of the many reasons that movie was a classic (Matrix 4 coming, baby!).

But the biggest problem with this script is that 75 pages into it, I stopped and thought to myself, “I know I’ve read this somewhere before.” I went into my archives, did some research, but eventually realized that, no, I hadn’t read it before. It was that the script’s beats were so familiar, it just FELT like something I’d read before. And that’s where I mentally gave up on the script.

A few of you have indicated I should add a “Is this produceable” section to my reviews since I’m moving into producing. It’s a great question with this script. Because it feels like a movie. But if I’m going to produce something, I’m looking for some element that’s unique enough to make the film stand out amongst the crowd. And I didn’t feel that here. This is very much Mission Impossible meets James Bond. A few years ago, the female lead might’ve helped it stand out. But now everyone’s writing female action leads.

Then again, who knows. John Wick was the most generic action movie plot ever. A retired assassin comes back to kill a bunch of bad Russians. And after the Action Showdown Contest, one of the conclusions we came to was that it’s really hard to make an original action movie. So I suppose the answer to this question is in the eye of the beholder. We’ll have to see what happens.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When writing hacking scenes, avoid a bunch of character + computer screen gobbledy-gook that sounds like hacking. Stuff like, “Did you close down the firewall?” “I’m still trying to find out if he’s using a password sniffer!” In my experience, that stuff never works. Instead, you need to create a situation – preferably something visual – that the reader can understand. Maybe this isn’t the best example, but in The Social Network, instead of Mark Zuckerberg writing some weird techy hacky program in real time, Sorkin had him competing against six other people in a circle of computers in the midst of a drinking contest. That’s always going to work better than literal lines of code.

Genre: Drama/Mystery/Sci-Fi

Premise: (From Black List) A soldier, forced to relive her worst day in combat, begins to question her sanity when the VR simulation she’s experiencing doesn’t match her memory of the mission gone wrong.

About: This script finished #2 on this past year’s Black List, receiving 20 votes. Co-writers Reiss Clauson-Wolf and Julian Silver seem to know this subject matter well. They are both story editors on the TV show, “SEAL Team.”

Writers: Reiss Clauson-Wolf, Julian Silver

Details: 103 pages

It hasn’t hit me until now how weird the 2019 Black List is. Ever since agents realized that the Black List could be used to advertise their writers’ screenplays, they’ve relentlessly promoted the material they’ve wanted to promote. And that material wasn’t always the best material. It was the material representing the projects the agencies most wanted to make.

We’re seeing the first Black List since 2007 that isn’t influenced by agents. And I’m not going to know for sure how much of a difference that’s made until I read a couple dozen more scripts from the 2019 Black List. But based on these first two scripts, I can tell you they’re unlike anything that made the top two slots in previous Black Lists. The only people promoting scripts now are managers. And managers don’t have the same motivations as talent-focused WME and talent-focused CAA.

If anything, these scripts feel like specs. And the commonality I’ve found with specs over the years is that they’re a little messier. They tend to be written by newer writers who haven’t yet learned how much is required to make a script great. And that makes sense. Because if you’re a seasoned writer, you’re making big money on assignments. You don’t have time to write specs.

With that said, Field of View is a lot better than the number 1 script on the list, Move On.

Mel Harris is a NAVY officer in a team of four men running into a house in Afghanistan during the war. The team charges into the house and starts throwing grenades everywhere. Mel sprints into a room, sees an Afghan fighter, shoots him dead. She then takes position near the window before hearing an explosion in the other room. She runs into the other room to see that one of her team members, Connor, is dead.

Cut to 3 years later.

Mel, who bartends at the local watering hole, is now the physical manifestation of PTSD. Anything can set her off. And something does. A road rage incident leads to her slamming her car into the back of a Beamer then challenging the driver to a fight. He simply calls the cops. The next thing Mel knows, she’s facing 10 years in prison.

Unless she wants to participate in a new military experiment called VICTOR – a virtual reality program that makes you relive your worst moment in battle over and over again until you’re able to move past it. The idea being you’ve finally conquered the event that triggers your PTSD. Mel decides VICTOR sounds better than 10 years in prison, so she heads over to the lab, gets hooked up, and she’s right back in Afghanistan 3 years ago.

Mel sees the events as a third party. The event being displayed is based on all the soldiers reports of what happened. But Mel starts noticing little things wrong here and there. When they breach the house, for example, the wrong soldier is in the front of the line. Or the nearby house is the wrong color. VICTOR’s head scientist explains that there are little quirks in the program and not to worry about them. But something doesn’t feel right about the whole thing.

In between VR sessions, Mel hangs out with her old team, the soldiers who were there that day. Two of them, Ellis and Bryant, seem miffed by her participation. Ellis, in particular, thinks she should stay away from it. Something about Ellis’s insistence makes her want to go back. And each time, she gets further and further into the simulation, getting closer to the event that killed her team member.

When the doctor leading the simulation loses faith in Mel, they consider cancelling the program. But Mel is determined to find the truth of what happened that day. In her final simulation, she watches every little moment carefully, only to learn that she’s been lied to. It wasn’t the enemy who killed Connor. It was one of her own men!

I like virtual reality ideas. There are a lot of unique things you can do with VR in storytelling. And a nice bonus is that nobody’s made the preeminent virtual reality film yet (hint hint – potential script idea for The Last Great Screenwriting Contest?).

What I liked about Field of View is it took a very uncomplicated approach to the concept of virtual reality. This is a mystery. Somebody’s dead and our hero isn’t convinced that the murderer is who she thought it was. The virtual reality is a way to go back and get more pieces of the puzzle so that the viewer can solve the mystery.

But the suspect virtual reality technology and Mel’s faulty memory give the story an “unreliable narrator” quality that adds an extra layer to the mystery. Even if we figure out who the murderer is, is that actually the murderer? Maybe our hero is misremembering. I thought the writers did a really nice job of playing with that possibility.

From a technical aspect, the writers take a chance by writing all the virtual reality scenes in bold. It’s always a risk when you break from traditional formatting because nobody’s going to be mad at you if your formatting is normal. But there will always be someone who’s annoyed when you break from tradition. So it’s a risk. However, because the VR scenes never lasted too long, it didn’t bother me. It would’ve been a different story if half the script was in VR. Nobody wants to read half a script in bold type. It’s always a case by case basis when you’re doing this stuff so really think hard if you’re going to do something different. It may be more trouble than it’s worth.

The script had a couple of nice twists. One of them was that Mel was secretly in love with Connor – the man who was killed. Mel is married in this story and, in the past, I’m not sure writers could’ve gotten away with that. With a male character, sure. But not with a female character. That’s changing though. And I liked that here because it helped make the character more complex.

The second twist is that the murderer isn’t who we think it is. The script does a good job putting all of our focus on: Did the Afghan soldier kill Connor or did Ellis kill him? Ellis was the sketchy one. He was always telling Mel not to mess with the virtual reality program. So we’re trying to figure out if he did it or not. It turns out it was a misdirect, though. It was one of the other soldiers, someone we liked. That gave the ending a nice little bump.

Unfortunately, the script never rises above “good.” It seems like there was another level to find here and we never got to it. There were also things that annoyed me. The opening scene, which is the first time we see the house breach, is purposefully vague. The way it’s written is like reading through fog. They knew we couldn’t know too much about what happened or else there’d be no mystery. But it works against the script because I didn’t even know that Connor died in the opening without going back and reading it a second time. There’s vague and there’s just plain confusing. The opening to this script was straight up confusing.

Still, the script gets points for giving us a common story (soldiers home from war try and move past a war tragedy told through flashbacks) in a slightly different way. The virtual reality gives the movie just enough of a unique flair that it stands out from all these other war scripts.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the more overused character descriptions I encounter is some version of, “DOUG, 38, once a strong man, but now looks weak and defeated.” (there are TWO descriptions in Field of View like this). It’s a VERY common way to describe characters. And whenever something becomes too common in writing, you want to avoid it. Like when Shane Black was writing clever asides in his action paragraphs, you didn’t want to be the guy who was ALSO writing clever asides in his action paragraphs. I get the appeal of this description. It gives a clear vision of the character. Everybody knows what a “broken” person looks like. But if you want to stand out, you have to find other ways to say things.