56 pages in. Who would’ve thought?

This weekend, I watched “The Platform.”

It’s a movie on Netflix with a clever premise. You agree to be a part of a 6-month experiment and, if you finish, they give you something important you need in life.

The catch is you don’t know what the experiment is until you’re in it.

So our hero, Goreng, wakes up in a concrete room with a roommate and a giant square hole in both the middle of the ceiling and the middle of the floor. We also notice a big number on the wall – 43. Before Goreng knows what’s going on, a giant table of food descends into the room and stops.

The giant table of food, however, is leftovers. Chicken bones and mostly eaten cake. Goreng watches in confusion as his roommate, the older conniving Trimagasi, ravenously attacks the leftovers.

What Goreng will soon learn is that the table of food comes down once a day, starting on the top floor with all the food. The table lowers every 60 seconds and each floor can eat as much food as they want during that time.

Goreng stares at the picked-over leftovers, the result of 42 previous floors of eating, and then asks the question all of us are wondering. “How many floors are there?” “200,” Trimagasi says. 200? If there’s only this much food on floor 43, how much reaches floor 100, floor 150, or floor 200? The thought is too scary to think about.

The story is obviously a metaphor for capitalism and it works well. Also, it’s a dream concept for a producer, which is why I got so jealous the second I saw it. A never-before-used high concept that takes place in a single location? It doesn’t get any better than that. You could shoot this movie for a quarter of a million dollars if you had to.

The movie seems to be getting a divisive reaction. The people who love it really love it. But when I tried to get my brother to watch it, he couldn’t make it past the ten minute mark. “It’s a guy in a room. Who cares?” He said. “I’m already bored.”

Because I have the 2-Week Screenplay Challenge on my mind, I imagined what it was like writing this movie and how it might be applicable to what all of you are dealing with.

My theory is that this was a first draft. It was a really good first draft – it probably had half-a-dozen polishes, otherwise known as “light rewrites” (change a scene here, alter a scene there). But you could feel the writer searching for interesting story elements as the story moved into its second half.

What really gave it away was the ending, which was the kind of ending writers write when they don’t have an ending. They convince themselves they’re being thoughtful and “challenging” the audience, when in reality they throw in some vague nonsensical finale and hope the audience does the work for them.

What I’ve found with endings is that you never nail them on the first draft. They alway take numerous drafts to figure out because endings are payoffs to setups. This requires you to go back to the beginning, set some things up, then pay them off in the climax. Which means starting a new draft so you can do that.

Then you learn your new setups aren’t perfect so you start to fine-tune them. And that takes more drafts.

And here’s what I’ve ultimately found. You can’t write a great second half until you know exactly how your movie ends. Because everything needs to be setting up that final sequence. If you’re not 100% clear on what that final sequence is, your second half is always going to be squishy.

All of this is to remind you that it’s okay to be messy right now. It’s okay, as you make your way to the climax, if none of the puzzle pieces are fitting together the way you want them to. That will come. I promise you, if you choose to keep writing this script after this draft, it will come.

The only thing you need to worry about right now is having fun. Don’t take this process so seriously or you’re going to hate yourself and want to give up.

And if The Platform truly was a first draft? It shows you what’s possible with a strong concept. You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to exploit as many cool things about your concept as possible. Get into your audiences’ heads. What do you think they would want from your concept? Give them that. I was curious about what the table looked like on the 200 level. They put our characters on the 200 floor later so we see that. That’s how to exploit your concept.

So keep writing. I want one of you to have a featured movie on Netflix. It’s not going to happen unless YOU. KEEP. WRITING.

48 pages in!

It’s likely that you are in one of two mindsets. You’re on that first draft adrenaline rush where you’re writing down anything your imagination can come up with, feeling like a young Tarantino in the process.

Or you’re freaking out about the fact that you don’t have nearly as much story as you thought you did. You’re a fraud. You don’t know how to write. Every scene you’ve written sucks.

The Writer’s Inner Critic absolutely LOVES this part of the process, the part where you doubt yourself. It gets to remind you just how terrible you are so it can ensure that you never put yourself on the line or attempt to do anything big with your life. This way you stay at home in that safe little bubble, your biggest task each day figuring out what to eat for dinner. Chic-fil-A or In and Out.

Here’s some good news.

No screenplay has ever been written IN THE HISTORY OF MANKIND that didn’t have at least five mental breakdowns from the writer, who was convinced that both a) this was the worst idea ever for a movie and b) they were a fool to think they could ever actually write it.

So if you’re feeling any of these things, you’re in good company.

Here’s what you have to remember. And it’s something I figured out through my own experiences.

With each draft, you realize that you can move stuff up. That big moment that happens on page 30? You could move that up to page 15. That thing that happens at the midpoint? That should actually be your first act break.

And then the next draft, it happens again. Your new midpoint sequence? It could probably be moved up to page 45.

It’s only after three or four drafts, when you’ve packed your script with a big solid game-changing moment every 15 pages, where you start to feel the power of your original vision. That’s where the movie becomes real in your head.

You’re nowhere close to that at the moment. You’re still trying to get a sense of what your story is about. And you’re doing that by writing eight pages a day. Those pages are like little notes to yourself about what your story can be.

So stop worrying if your script feels dumb right now. It SHOULD feel dumb right now. It’s the dumb version of your movie. The smart awesome version of your movie is several drafts away. But you can never reach that awesome version unless you first finish this one.

Ignore your inner critic and KEEP. ON. WRITING!!!!

P.S. I saw the craziest thing the other day. It was a line of 71 cars at the In and Out drive through in Culver City. I counted every one.

Congratulations to everyone who’s kept up!

Even if you haven’t gotten to page 40 yet, good job for staying with the challenge. I’m proud of you.

It’s time we got real, though.

You’re in the thick of it. Act 2. This is where the big gaps in your story start rearing their ugly head. There are some sections you knew you didn’t know and now you’re learning about whole other parts of your story that aren’t as clear as you thought they were.

This means that you might have 20, even 30 pages, before you reach the next part of your story you’re actually familiar with.

A few of you asked that very question yesterday. The next checkpoint isn’t for a while. What the heck do I write in the meantime?

One thing that can help you fill up lots of screenplay real estate is subplots. Subplots are basically storylines that involve your hero and secondary characters.

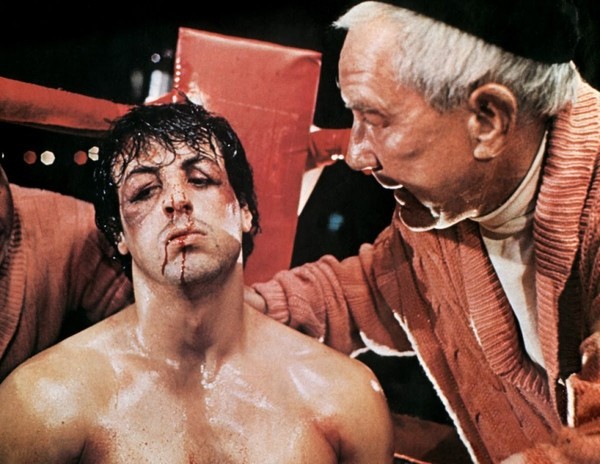

If you look at Rocky, one of the brilliant things about that movie is that there were four characters OUTSIDE OF ROCKY who all had fleshed out roles. You had his girlfriend, Adrian, of course. You had Mick, his trainer. You had Pauly, his alcoholic best friend. And then you had Apollo Creed.

Whenever you needed a scene, you could explore a component of any one of those relationships, like after Rocky gets chosen by Creed to fight for the heavyweight championship, a desperate Mick comes to Rocky’s place and begs to train him. Or when Pauly gets wasted beyond comprehension at a local bar, Rocky has to rescue him.

Depending on what kind of movie you’re writing, you might even have second-tier subplots (or “sub-subplots”). These would include characters outside of your hero. For example, in Rocky, Adrian is Pauly’s sister. The two of them have their own family issues, which results in a few dustups over the course of the movie.

If you don’t have subplots to go to, it probably means you’re not giving your secondary characters enough to do. Rethink that aspect of your story and you’ll have more scenes to write.

Also, don’t be afraid of holes in your narrative.

Sometimes they can actually work to your advantage.

Think of it like this. If you promise that a big moment is coming up, the lead up to that moment is often just as engaging as the moment itself. It’s like a roller coaster ride. They make you wait in that line for an hour before you get on the ride. The anticipation built up during that wait is sometimes better than the ride itself.

So if you promise that a heist is coming up, we’re going to stick with you. Your job, in those pages leading to the heist, is to come up with scenes that cast doubt on the job being successful. I call these “Uh-oh” moments. Everything’s looking good but then, “Uh-oh. They’re forced to move the heist up a week after the bank changes its brinx truck pick up times.”

They go to pick up the getaway car. But, uh-oh, the getaway car they thought they were getting didn’t come through. They’ll have to use one of their own cars now, increasing the chances that someone will ID them. Oh, and their safe-cracker? Uh-oh. He comes by and says he wants a bigger cut of the prize. They don’t want to give him that much. What do they do now?

Once you know where you’re going with the story, bring the reader in on it so they can anticipate it. Then, in the meantime, fill in gaps with subplot scenes and scenes that introduce obstacles which make achieving the goal harder. Don’t worry, we’ll stay with you if the moment you promised us sounds exciting. It’s when you don’t tell us anything that’s coming up that we lose interest.

It’s the weekend. Be daring and write 10 pages these next couple of days instead of 8. I dare you!

INT. DARK MYSTERIOUS ROOM – NIGHT

Close up on a pudgy man, DAVE, 35, tied to a chair, groggily waking up.

In front of Dave are two doors.

Someone appears behind Dave, untying him. This is ALISTAIR, 60, a “former game show host” vibe to him. After Alistair finishes untying Dave, he takes a position in front of him.

DAVE

Where am I? How did I get here?

ALISTAIR

Not important, Dave. If that is your real name. What is important is that behind me, there are two doors. These doors are the only two ways for you to leave this building. You will have to choose between them. Behind the first door is a room that contains a version of coronavirus that is 100x more contagious than the normal strain. The chances of you getting out of that room without contracting the virus are less than zero. Behind the second door—

DAVE

I pick the second door.

ALISTAIR

But I haven’t told you what’s behind the second door yet.

DAVE

I don’t care. There’s nothing you can tell me about that second room that’s worse than the first one. I’m ready. Room 2. I’ve made my decision.

ALISTAIR

Are you absolutely sure?

DAVE

I’m positive.

ALISTAIR

Because in Room number 2 you will be forced to sit down in front of a computer and not leave until you’ve written the entire second act to a feature screenplay.

Hold on Dave’s face.

He then BURSTS UP, SPRINTS PAST ALISTAIR, YANKS DOOR 1 OPEN AND DISAPPEARS INSIDE, the door slowly inching back closed…… CLICK.

Fin.

Yes. All of us can sympathize with Dave. Act 2 is scary.

Which is why I’m going to help you get through it.

Here’s your screenwriting lesson of the day.

The stronger your hero is in his want for something, the better your second act is going to be.

That’s because when your hero wants something badly, all you have to do as the writer is follow him as he attempts to get that thing.

So in The Equalizer, one of my favorite screenplays, once we set up that Denzel is going to go after all the corrupt forces taking advantage of the people in the city, the second act writes itself.

You just write a scene where dirty cops shake down a local Chinese restaurant for money as a “protection” fee. Then have Denzel corner the cops in the alley and make them give the money back. The cops say no and now you have a scene on your hands (Pro Tip: The “no” is what makes a good scene. “Yes,” there’s no scene. If they say, “No,” the two sides are forced to battle.).

But let’s say you don’t have a traditional hero-going-after-a-goal narrative. What do you do then? Uncut Gems kind of falls into this category. The goal is coming more from the bad guys, the bookies. They want their money from Adam Sandler. So they’re driving the majority of the narrative.

What you want to do in these cases is take the overarching goal-driven approach that’s usually dictating the narrative, and apply it to individual scenes. You then keep doing that over and over again for each scene. As long as you have a character with a strong goal in a scene, you’re going to write good scenes.

For example, in Uncut Gems, Sandler has a big blow-up with his mistress after he thinks she cheated on him. He then goes back to his wife, who he’s divorcing, and he tries to get her back. THAT’S THE GOAL OF THE SCENE. He realizes his mistake with this other woman. He wants to call off the divorce. His goal is to convince his wife that he’s changed and that it’s a good idea to stay married.

It’s a simple scene but a good one. And all that’s happening is the writers are making sure that there’s an actual directive in the scene.

Another thing you can play with in the second act is CAUSE AND EFFECT. You want to throw something hard at your hero, knocking them off their path, which then forces them to reestablish order – get back on track.

Parasite. They find a family hiding in the basement, jeopardizing their ability to continue working in the home. This is the cause. You then use the next 1-5 scenes for the effect. They tie the secret basement family up. Should they kill them? Let them go? Might they come back and reveal their scam? The nice thing about cause and effect is that you can stretch it out for a long sequence, get a good 20 pages out of it if you want to.

Finally, the second act is where you’re digging into the relationships, specifically the unresolved issues between the characters. A lot of writers are scared to put two characters in a room for a no-frills dialogue scene. And they should be IF THERE’S NOTHING UNRESOLVED ABOUT THAT RELATIONSHIP.

But if you’ve constructed two characters with something unresolved – whether it be differing political views, differences in how they approach life, abusive relationship, they have a complicated past, they avoid problems in their relationship, they plain don’t like each other, or anything that creates tension between the characters – these character-based scenes can be highly entertaining.

TV is really good at this but feature writers are scared of it for some reason.

I was just watching “Devs,” Alex Garland’s show on Hulu. In the show, Lily’s boyfriend is murdered by the company they work for. The only person she trusts who can help her prove this is her ex-boyfriend, Jamie, who she left on bad terms. Their unresolved past means that every time they’re in a scene together, there’s tension in the air. That’s the kind of stuff you want in your second act.

The most important thing of all though is to KEEP WRITING. I’m seeing people say they’ve only gotten to page 12 or 14 or whatever in the comments. Unacceptable. Again, I’m not asking you to write Chinatown. I’m asking you to write a first draft quickly. That means some sacrifices will need to be made. One of those sacrifices is to stop doing things the way you’ve always done them. Do them the way I’m telling you. You can decide after this is over whether my way or your way works better. But you’re not going to improve as a writer if you don’t try new things.

The only reason you wouldn’t be writing is if you’re being too critical on yourself. Don’t listen to the critical side of your brain right now. He’s worthless. Listen to Carson. He’s saying, “Keep writing. No matter what. Keep writing.”

Flavor Bin!

Yes!

It’s Day 4 of writing a screenplay, baby!

Is there any better feeling than writing a screenplay? Don’t answer that. But seriously. When you’re cooking along…. when those ideas are hitting the page like raw chicken hitting the barbecue, that seasoned smoke wafting up into your nostrils and you can’t wait to slather some sauce onto that delicious cascade of meat and nom nom nom your way to culinary heaven. That’s why we do this.

Now since we’re writing 8 pages a day, you should be passing through one of the most important sections of the screenplay today – the first act turn. The first act turn occurs between pages 24 (for a 100 page screenplay) and 30 (for a 120 page screenplay) and denotes the moment where your hero begins his journey.

Indiana Jones going after that Ark. Ben Affleck starts coaching the team in The Way Back. The three friends go out to retrieve their father’s super expensive drone in Good Boys.

If you’re not writing a hero’s journey type script, the first act turn instead denotes a directive being put in place. In one of the biggest spec sales from last year, “Shut In,” about a woman who gets shut into her closet by her druggie husband, the first act turn is the moment where the husband’s violent friend enters the house and she enacts a plan to get out and save her children.

And then there are more complex scenarios, where you hand the “plan” over to the antagonist. Since they’re the active one in the story, it’s them who enact the first act turn in the journey. That’s what happens in The Invisible Man. Cecilia is not active for the first half of the screenplay. The plan – stalking and driving his ex-girlfriend insane – comes from the boyfriend. So the first act turn is when the ex-boyfriend begins the process of stalking her.

The point is, some sort of clear direction needs to be established in today’s eight pages. Otherwise you’re going to have a script that loses its engines and dives towards the ocean and no matter how many times the automatic alert system tells you to, “Pull Up! Beep-beep. Pull-up! Beep-beep.” it’ll be too late.

Moving forward…

One of the topics that keeps popping up in the comments is whether to go back and rewrite some of the stuff you’ve already written.

Should you be doing this?

Under normal circumstances, I’d say yes. It’s actually a nice way to ease your way into the day’s writing session. Cause you look at a previous scene, it gives you a better idea for a setup or a line of dialogue. Now you’re typing. So it isn’t difficult to ride that momentum into writing some new pages.

But we only have two weeks to write this. And I’m guessing a lot of you are behind schedule. I hope not. But I’m hearing little birdies chirp in the comment section that tell me otherwise. And the main reason you don’t have pages is because you’re doing things OTHER THAN writing pages, with rewriting being one of those things.

Here’s the sneaky problem with rewriting pages: It’s fool’s gold. It FEELS like writing. But, at the end of the day, you haven’t written anything new. Or, at least, you’ve written less. So let’s not do any rewriting. Make the focus of each day tackling the blank page and that’s it. That strategy is what’s going to allow you to write a script in two weeks.

For our final topic of the day, we have to thank Jonah Hill.

Hill, who’s sold a few screenplays in his day, has been adamant about the fact that he’s writing while quarantined. And recently he revealed a great writing tip. He calls it “the flavor bin.”

The “flavor bin” is a separate document which contains all of the “too outrageous” ideas he’s come up with for that script. When he gets stuck, he heads on over to the flavor bin to see if any of the ideas can be added to the script.

A flavor bin idea for James’ Cameron’s “Titanic” might be: Someone falls overboard and gets attacked by a shark.

That idea doesn’t quite fit the tone of the movie. You could argue it distracts from the plot and the main themes of the movie. But it’s a great flavor bin idea. It gets you thinking. Regardless of whether you use a flavor bin idea or not, they tend to get the creative synapses in your brain firing, which could lead to some idea-piggybacking that eventually leads to an idea you do use.

It’s also a great idea for conservative writers. If you’ve ever been accused of writing “safe,” “bland,” or “predictable” scripts, you should definitely try adding a flavor bin to your screenwriting toolbox. Flavor bin ideas can take your script to places you never would’ve thought otherwise.

Okay, time to begin the day’s writing. You don’t feel like it? Don’t care. You’ve got so much to do today. Don’t care. You’re not inspired.

This process is not about how you feel. It’s about getting pages down. Whenever you run out of ideas, erase the inner critic and write whatever comes to mind. Even if it’s babble. Babble eventually turns sensical if you do it long enough.

Good luck. After today, you’re 25% done!