There MAY BE an update on a certain recently reviewed amateur script on Scriptshadow but I also may be sworn to secrecy and not able to talk about it. The good news is, we’ve got FIVE new amateur scripts to talk about AND we’ve got until Monday to read and vote. It’s a 3-day weekend here in the U.S. so that means no new Scriptshadow post on Monday. More time to read and write, I say!

If you haven’t played Screenwriter Showdown before, here’s how it’s done. This is a single weekend screenplay tournament where the scripts have been vetted from a pile of hundreds to be featured here, for your entertainment. It’s up to you to read as much of each script as you can, then vote for your favorite in the comments section. Whoever receives the most votes by Monday 11:59pm Pacific Time gets a review next Friday. If you’d like to submit your own script to compete in a future Amateur Showdown, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

I’m vacillating between reviewing Dark Crystal and Carnival Row on Tuesday, two unique fantasy TV shows with gigantic budgets. Which one are you more interested in?

Enjoy the long weekend!

Title: The Last Pookie Sinclaire

Genre: Crime/Thriller

Logline: Pookie Sinclaire painted his final masterpiece ten days before his death. This is a story about a bunch of people trying to steal it.

Why You Should Read: So you can help me with the logline. All joking aside, I love this site. This script is proof of that. There are numerous principles from Carson that I’ve tried to include in this script. Then the other day, he went and posted about dialogue! So I thought, okay, let me toss this into his inbox and hopefully I get to run the gauntlet. Because who better to gauge my use of the site, than a bunch of people who regularly contribute to it? Cheers!

Title: Grisly

Genre: Thriller

Logline: Trapped in a secluded cabin, a hunter and his daughter fend off attacks from a relentless grizzly bear hell-bent on vengeance for the death of its cub at their hands.

Why You Should Read: I vividly remember the sensation of being stalked by a black bear during one summer visit to the Sierras… Well, stalked is a bit strong – it passed me within grabbing distance. Still, the feeling of power in its gait, the potential explosion of ferocity if it so pleased was unsettling and stuck with me ever since.

Title: Vice Life

Genre: Sci-fi/ Drama

Logline: A clean-cut collegiate wrestler becomes addicted to virtual reality episodes of an MMA superstar’s increasingly unhinged life.

Why You Should Read: Carson, in a recent review of a Sci-fi/Drama script you wrote that while it’s a tough genre to pull off, you ‘root for these scripts because there isn’t a lot of science-fiction for adults out there.’ I wholeheartedly agree with that statement and so present a script that’s got an interesting sci-fi hook while dealing with weighty themes.

Virtual reality and mixed martial arts are burgeoning forms of entertainment that have gone from strength to strength, and while they may not be to everyone’s taste, this script explores universal themes of identity, ambition, failure, jealousy and betrayal that everyone can relate to.

I’m confident that it walks the tight-rope between being serious and entertaining without falling into the trap of being tedious. But if I’m wrong, what better place to find out than the Scriptshadow community.

Title: GUN CRAZY

Genre: Drama

Logline: A librarian with a PTSD-driven obsession with gun culture finds herself in a unique position to save the day when an active-shooter situation develops at the school where she works.

Why You Should Read: This is my modern take on TAXI DRIVER that I hope will elevate discussion about mental health and gun violence issues, and hopefully do so without coming across as gratuitous, which I understand is a fine line to walk given the subject matter. I’ve written tons of stuff in various genres without yet attaining the brass ring, and I know this is more arthouse than commercial, but sometimes you just have to tell your story. It’s got a powerful lead role for female talent, and I think lots of potential in the festival world.

Title: The Women

Genre: Post-Apocalypse

Logline: After years of being held in captivity, a mother and daughter escape to find the world in apocalyptic ruin, overrun by monstrous predators and fanatical men intent on capturing them.

Why You Should Read: Why it deserves a shot? I can’t imagine anything scarier than gaining brief reprieve from a living nightmare, only for something worse to pop out further down the road. That’s the basis for this story’s concept, which hopefully plays as a tight genre script with genuine depth and frights. It also feels like a prescient time to feature writing with female characters battling against a long and continued history of male induced oppression, so I’m hoping these things coalesce into a rewarding read.

We’re sticking with Star Wars, folks, since that was our theme for the Scriptshadow Newsletter. If you didn’t receive the newsletter, go here to find out how. Now I’m well aware that today’s topic is a contentious one. I never thought a screenwriting term would become synonymous with the destruction of one of the biggest franchises of all time. Yet Rian Johnson’s brazen decision to zag at every plot point we thought The Last Jedi was going to zig on, introduced the term, “subverting expectations” to the general public.

What expectations am I talking about? Instead of Luke accepting the lightsaber, he throws it away. Instead of the main villain thriving and growing stronger, he’s killed in the middle of the movie. Instead of Rey’s parents being relevant to the mythology, she’s a nobody. Instead of Luke using his massive knowledge of the Force to battle Kylo and defeat the First Order, he’s a hologram who was never really there.

While some moviegoers found these choices exciting, most fans had a problem with some or all of them. Which is too bad. Because you know what? Subverting expectations is one of the single most important tools in a screenwriter’s arsenal. If you don’t know how to subvert expectations, you shouldn’t be writing movies. The opposite of a subverted expectation? Is a met expectation. And if you meet expectations over and over again in any script, you are boring your audience. These people didn’t come to your movie to see exactly what they expected. They came to be surprised on some level. That’s the exciting part of moviegoing. It’s, “Luke, I am your father.” It’s “I see dead people.” It’s Thanos gets killed within the first 20 minutes of the movie.

So the question becomes, why is it that Rian Johnson’s expectation subverting failed so badly yet there are many instances in film where subverted expectations not only worked, but created iconic moments? And how can you effectively use subverted expectations in your own screenwriting?

The first problem here is something you won’t have to deal with until later on in your careers when you become a 7-figure quote screenwriter. Rian was playing with a beloved world and characters. Therefore, he was subverting expectations based not just on this movie, but on many that came before it. I don’t think Rian respected that as much as he could’ve. He seemed to be more into doing what he wanted rather than what was right for the franchise.

However, one of his early choices is something that is relevant to any writer. And that is never prioritizing a surprise over character. Luke throwing the lightsaber away in a comical manner isn’t something Luke Skywalker would do. Now Rian would probably argue that it’s something HIS version of Luke Skywalker would do. But it’s clear at this point that he fundamentally didn’t understand the character. The actor who played Luke publicly contested this over 30 times. My feeling is that Rian wanted Luke to throw that lightsaber over his back so badly that he created that moment then retroactively built his Luke around that choice. The lesson here is to get into your character’s head and be honest with what he would do in that moment. If you choose to subvert expectations in a way that is inconsistent with that person, the audience won’t buy it.

The next big lesson with expectation subverting is that you don’t want to do it too much. Because if you do, two things happen. One, we start to EXPECT the subvert, which defeats the whole purpose of it. And two, we become AWARE OF THE WRITER. A subverted expectation is a heightened moment that draws attention itself. Do it over and over and the audience starts thinking about the person doing it rather than characters experiencing it, which breaks the suspension of disbelief. The very nature of subverting expectations requires that you carefully pick and choose the moments when you do so. Rian relied on subverting so often that each successive surprise lost impact.

To expand on that, you need to meet the expectation to subvert the expectation. Stories are a dance. And most dances follow a set sequence of steps. This is why it’s okay to write 30 pages of screenplay that follow a traditional storytelling pattern. You’re luring the audience into a sense of comfort. But there are times when you’re dancing that you improvise or break into freestyle. And the same goes for storytelling. Every once in awhile, you throw something at the audience that they don’t see coming. Let the audience be right about a bunch of things so that when you do subvert an expectation, it’s a surprise. Rian was so set on making some arthouse Star Wars masterpiece that he forgot the basics. And the basics dictate that, for most of your screenplay, you are following a structure.

This next decision by Johnson is probably the biggest because it implied a disregard for the well-being of the Star Wars brand. And that was killing Snoke in the middle of the movie. Clearly, this was going to be Rian’s defining moment, the thing that pushed Last Jedi into ‘classic’ territory. But by destroying the ultimate villain, he drastically lowered the stakes. If the puppet master stops pulling the strings, there’s no more puppet show. Which is why YOU DON’T WANT TO SUBVERT AN EXPECTATION IF IT LEAVES YOU STRANDED ON AN ISLAND LATER ON. Sure, it would be shocking to kill John Wick in the middle of John Wick 3 and have Halle Berry’s character take over the protagonist role. But is that in the story’s best interest? Make sure to project where your subverted expectation takes you before you write it. Because, if you’re not careful, you could kill your movie right then and there.

Finally, we have what Rian was accused most of, and that’s subverting expectations for the sake of subverting expectations. What does that mean? It means that the act of subverting the audience’s expectation is more important to the writer than writing what is best for the story. It means going into a scene and saying, “I need to do the opposite of what the audience thinks I’m going to do. I’ll try to have it make sense but even if it doesn’t, I’m doing it.” For a movie to work, the choices need to feel organic to the story. The characters need to act in a way that’s consistent with how they’ve been acting. Once you start messing with that cause you want to jolt the audience, you’re playing with fire.

Now that does’t mean there aren’t shades of gray here. Sometimes you know your script needs a jolt and maybe that jolt doesn’t entirely jibe with what your characters would do, but you go back and add a few set-ups that make it, if not believable, plausible. But if you get sloppy, you get the Charlize Theron Is A Superhero Too twist in Hancock. I don’t know if Rian set out to subvert expectations just to do so, but if this were a court case, there sure is a lot of evidence to support that claim.

Okay, let’s wrap this up. Screenwriters everywhere – YOU SHOULD BE SUBVERTING EXPECTATIONS IN YOUR SCREENPLAYS. To what degree will depend on the genre, the type of movie you’re writing, and how good you are at the practice. Just like some writers are better at dialogue than others, some writers are better at subverting expectations than others. They effortlessly do it in a way that’s both invisible and believable. Just remember that, above all else, a subverted expectation must feel organic. As long as the choice is a natural extension of the story, we’ll love it. Now go subvert away!

Yo, do you have a logline that isn’t working? Are those queries going out unanswered? Try out my logline service. It’s 25 bucks for a 1-10 rating, 150 word analysis, and a logline rewrite. I also have a deluxe service for 40 dollars that allows for unlimited e-mails back and forth where we tweak the logline until you’re satisfied. I consult on everything screenwriting related (first page, first ten pages, first act, outlines, and of course, full scripts). So if you’re interested in getting some quality feedback, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “CONSULTATION” and I’ll get back to you right away!

This is the LONGEST newsletter I’ve ever done. There was so much Star Wars news to talk about that I couldn’t stop myself. Mandalorian, Episode 9, Rian Johnson. It’s all in there, baby. Then, of course, I had to talk about The Matrix. I mean, duh. I also rank August’s new trailers from worst to best. Anyone want to guess what my favorite was? I also review a recent sci-fi spec sale that got a DOUBLE [xx] WORTH THE READ. It’s a great spec to read if you want to see what sells. Also I tell you who bought it and why you want to send YOUR future action specs there. I’ve got two great screenwriting tips of the month, one about how to create awesome characters, the other about handling the “Bermuda Triangle” section of the screenplay. Oh! And there’s a consultation deal in there for four lucky people. This is a really good newsletter.

So check your Inboxes! If you don’t receive the newsletter within the next hour, make sure to check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders in your e-mail program. If you can’t find it there, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you. Enjoy!

p.s. For those of you e-mailing me saying that you keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several invisible reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter.

SCHEDULE UPDATE – The Thursday Article is going to get pushed back to late Thursday afternoon. Labor Day Amateur Showdown will start early Friday evening and go through Monday (Labor Day). So get those scripts in if you want to be the next Cop Cam! Instructions here.

Genre: True Story

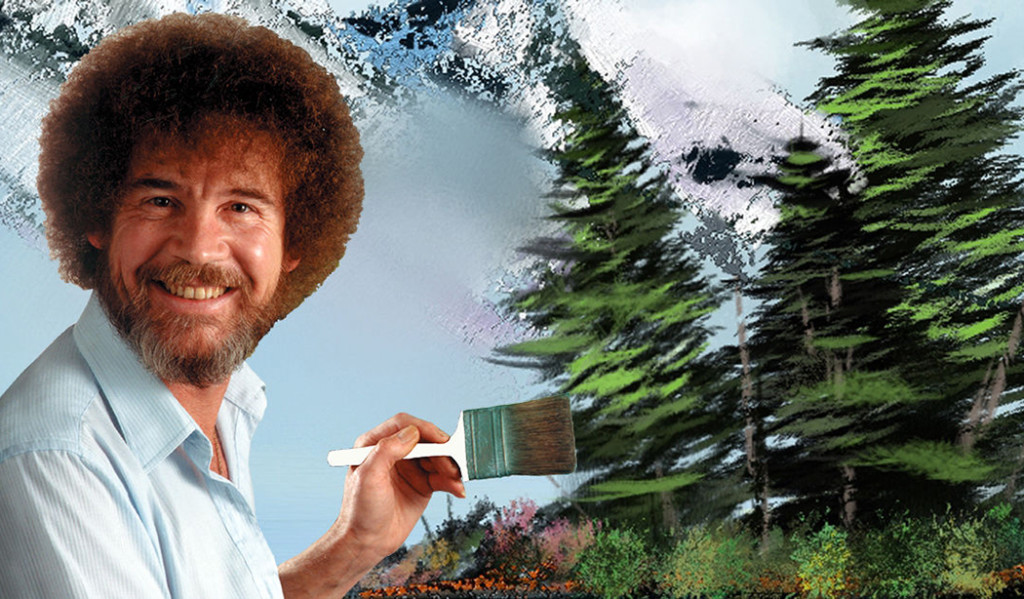

Premise: After Bill Alexander’s long-running show “The Magic of Oil Painting” was cancelled by PBS and replaced with Bob Ross’ show, “The Joy of Oil Painting,” Alexander accuses the soft-spoken afro’d Ross of stealing his act, inciting a bitter dispute that changed the lives of both men forever. Based on a true story.

About: This script made the Black List last year with 10 votes. Shawn Dwyer

is just starting to make a name for himself. He had another script, 73 Seconds, pitched as “Hidden Figures” meets “Spotlight” that got a producer attached. However, this script hasn’t yet secured a buyer.

Writer: Shawn Dwyer

Details: 112 pages

It’s fun reading these Black List scripts that are still searching for buyers because you can evaluate what it is about the script that gets one side of the industry excited but not the other. And this goes both ways. There will be specs that sell for a lot of money that don’t make the Black List. It happens all the time. The fact that this hasn’t sold implies that the subject matter is too obscure. Bob Ross is a cult hero. But he’s not necessarily a household name. I liked the concept here. The idea of two people sparring in an arena as peaceful as painting has a nice ironic ring to it. Let’s see if it’s any good.

We start in Prussia. 1927. Some boys, including our hero, Bill, are playing around in the forest when they find the remains of some old World War 1 equipment. In the midst of them joking around, one boy finds a grenade, prepares to throw it, only to have it blow up in his hand, instantly killing him.

Cut to 1982 and Bill, now 60 years old, is doing a landscape painting on PBS. In the middle of the painting, Bill stares off into nothing, only to snap out of it 60 seconds later. Apparently, this sort of thing has been happening a lot lately because a PBS suit sits him down to tell him he’s being replaced by an up-an-coming painter named Bob Ross. If it’s any consolation, they tell Bill, Ross used to be a student of his.

Determined to keep his gig, Bill meets Ross to give him the business. But Ross is just so chill, man. And after talking to him, Bill okays the transition, but on one condition. Ross will use Bill’s paint and hawk it on the program. That way, Bill still has an income source. After a few more flashbacks to Prussia, each one meant to convey how evil Bill’s father was, Bill learns that Ross isn’t living up to his end of the deal. In fact, he’s stolen Bill’s special paint mixture and called it his own!

This gives Bill an idea. He’ll sue Ross off the air! Bill’s lawyer says that if they can prove that Ross’s paints are replicas of his own, they’ll win the case. So Bill goes out and visits the totally chill Ross at his house, pretending to shoot a video with him so he can steal his paint. He barely gets a pale out of there and gets it tested. Indeed, it’s a replica of his paint. But by that point, it doesn’t matter. Bob Ross has become a superstar and there’s nothing Bill can do about it. Oh yeah, cut to 20 years later and Bob Ross dies of cancer.

Ooph.

Okay.

Whoa.

Um.

Not gonna lie. This was a rough read. I thought I was getting a comedy. But I guess this was a straight drama with the occasional flitter of humor (usually from Ross)?

There’s a lot wrong with this spec. A lot of mistakes young screenwriters can learn from.

For starters, there was a lot of repetition. After Bill gets fired, he and his wife seemingly have 50 conversations about what they should do next. Very little was happening in this section or the rest of the story, for that matter. Where’s the plot?

Plot can be described as a series of developments that evolve a story into something different from what it has been so far. The severity of the development will determine how radically the plot has changed. A basic example is a car driving on a freeway. Theoretically, we could follow that car for 90 minutes and call it a movie. In that case, there would be ZERO plot development and the movie would be boring.

However, let’s say the car blows a tire. Now we have a development. They have to pull over and figure out what to do about the flat tire. It’s not a severe plot development. But it does change the direction of the story slightly. Or let’s say we’re in the car, husband and wife are chatting. And, out of nowhere, the wife pulls a gun out and shoots her husband in the head. This would be a SEVERE plot development, right? It will have radically changed the direction of the story.

Yesterday, we had a writer who understood plot development. He knew that the story needed to change direction consistently, and sometimes radically. “Happy Little Trees” is the opposite of that. So little happens in this story that each time I had to turn the page it felt like I was lifting the heaviest barbell at the gym. After 20, 30, 40 pages of nothing happening, I knew each page was going to be a replica of the previous one.

After Bill gets fired, the next plot development – him wanting to sue Bob Ross for stealing his paint mixture – doesn’t happen for 60 pages. In the meantime, we’re getting scene after scene of Bill and his wife trying to figure out what to do. It’s simply not enough plot.

It’s not impossible to write good movies that are lightly plotted. But in order to do so, we really have to like the characters. Eighth Grade is a good example of a lightly plotted movie that still works because we empathize with the main character so much. I couldn’t find any reason to like Bill. He was negative. He complained a lot. He was whiny. I think the writer made the mistake of assuming that just because Bill’s job was taken away, we’d sympathize with and root for him.

But it doesn’t work like that. You still have to create a personality that we like on some level. Bill doesn’t have a single quality to him that allows that to happen. And it doesn’t help that Bob Ross is so likable. Sometimes what you can do in these movies is make the other guy a con man. So you’d have Bob Ross hypnotize the world, but when he’s alone with Bill, he’s a terrible person. We would then root for Bill to expose Bob. But Bob Ross is both good in public and good in private. So we don’t even want Bill to beat him.

I’m sorry but I have no idea why a writer would think we’d root for this person. It’s baffling to me, to be quite honest.

On top of that, there were tonal issues. The present day stuff has a light harmless feel to it, yet the flashbacks are brutally violent and uncomfortable for some reason. It was like two different movies. It only added to the struggle of keeping the pages turning.

There was a movie in here somewhere. Had the conflict between Bob and Bill been more intense, it would’ve at least given the screenplay some life. But between all the problems I mentioned and just an overall, way too relaxed, feel, I couldn’t get into this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Does your concept work better as a comedy? Sometimes we get blinders on when we come up with an idea. With some objectivity, you might find that the idea you’re taking so seriously actually works better as a comedy. This needed to be a comedy all the way. This is not a serious movie by any stretch of the imagination. Embrace the comedy. Make the characters more ridiculous. And have fun with it. This needed a fun touch.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Hit List) During an enormous wildfire, a fireman wrecked with guilt after the death of a colleague, searches for evacuees who have failed to leave their homes. But when he stumbles upon an isolated cabin, he makes a horrifying dis- covery — a young woman is being held captive inside – and he must now fight to get them both out of there alive before it’s too late.

About: Today’s writer used to be a sports journalist until he decided to place his head inside the guillotine known as screenwriting. Since then, he’s steadily moved his way up the ladder. He finished in the semi-finals of the Nicholl, got into writers room on the show “Helix,” and became a story editor on NBC’s “Manifest.” This script finished on last year’s Hit List with 16 votes

Writer: Bobak Esfarjani

Details: 91 pages

Fire scripts are all the rage these days! First Pyros and now this! Can somebody say “Fire Universe?” A forest fire pic. An in-depth true life adaptation of the Chicago Fire. A horror flick based on the Fyre Festival. A Firestarter sequel. A biopic on the first person to say, “Liar liar pants on fire” (I think that would be Jacob “Matches” Jones). Hey, we gotta find some way to compete with Marvel. Fight fire with fire. If this thing works out, you can move to water, air, ice – you name it.

I’ve always liked the idea of concepts set within the ticking time bomb that is a worsening fire. Yet nobody’s figured out how to do it right. There was that blink-and-you-miss-it Sam Jackson movie, Lakeview Terrace. But not much else. I can’t believe nobody’s written a recent movie on The Chicago Fire. I guess cows aren’t the most marketable villains. Anyway, grab your oven mitts and your smoke detectors. We’re about to find out if this latest fire flick burns down the house.

Firefighter Kyle is dealing with some massive PTSD. He believes it was his fault that his friend was killed in a recent fire. Kyle’s so distraught that even the biggest forest fire in California’s history can’t get him back up on the big red machine. When his small-town division is called in to help, Kyle stays back and cooks meals for his team’s return.

But when the fire takes an unexpected turn, people living up in the nearby hills will die unless Kyle helps evacuate them. So he drives around from home to home, yelling at people to evacuate. Kyle eventually stumbles upon a secluded cabin in the forest and knocks on the door. This is the home of Richard and Mary, two rednecks who have no desire to mingle with society. Oh, and they also have a secret. They’re keeping a 19 year old girl named Emily prisoner in a concrete room.

Kyle begins to get suspicious when Richard and Mary refuse to leave. Something doesn’t seem right. Then he hears a girl screaming. He charges into the house and finds the room, with a haggard Emily chained to the wall. Perhaps Kyle should’ve thought this plan through because pretty soon he’s whacked upside the head and wakes up in the room with Emily.

Meanwhile, Mary tells Richard they have to kill Kyle. But Richard thinks it’ll be too easy to trace Kyle here and they’ll get caught. Richard wants to kill Emily and get out of Dodge. But Mary has some strange obsession with Emily and refuses that option. This results in a stalemate and the two just stay in the house and do nothing – all while that raging fire gets closer. Back in the room, Kyle and Emily plan their escape. But bit by bit, he learns things about Emily that don’t add up, calling into question who the most dangerous person in this house really is.

A couple of weeks ago, I reviewed a contained thriller and preached the importance of evolving the plot. When you’re limited by geography, you have to have an “unlimited” plotting mindset. The story needs to twist and turn because we’re more likely to get bored when we’re in a stationary location.

Ashes starts out (spoilers) with our hero realizing that this family is keeping a girl prisoner. The first beat, then, is him trying to save her. This then evolves to him being stuck in the room with her. This leads to them scheming to escape. This evolves to them getting out into the house. This then evolves to ANOTHER firefighter arriving and helping them escape. This then evolves to Emily killing that firefighter, revealing the twist that she’s possessed. They were imprisoning her so she wouldn’t go into the world and kill people. This then evolves to Mary and Kyle working together to find her inside the fire-filled mountains.

I give Esfarjani a lot of credit. There wasn’t a single plotline that overstayed its welcome. We were always moving to the next stage.

But the big talking point with this script is obviously going to be the possession twist. Here’s the way I look at it. You get a maximum of two hooks per movie. The biggest forest fire in history forces a man to save a nearby family. That’s one hook. One of the houses he visits happens to have a couple who’s imprisoned a girl. That’s two hooks. The girl being a demon? That’s three hooks. Three hooks is where you get yourself in trouble.

It’s not that you can’t pull off three hooks. But it starts to look a little desperate from a reader’s perspective. You couldn’t keep us entertained with just two giant things going on, so you had to bring in one more? This can work IF the third hook is thematically connected to the story. But if it comes out of nowhere, you’re asking a lot of the audience. It would be like if in the third act of Godzilla, a superhero showed up. You’d be like, “Wait, so this is a superhero movie now?”

Having said that, screenwriting is an imperfect science. There’s no exact method for what an audience is willing to accept. Had you pitched me a movie about a guy realizing he was living inside a computer simulation and that once he freed their mind, he would fight everybody with kung-fu, I would’ve told you, “Thanks, but no thanks.” And Esfarjani leaves us enough breadcrumbs working up to the twist, that the possession makes sense. Which makes me think that maybe, just maybe, this could work.

The one big mistake Esfarjani makes is he doesn’t stay on top of the fire ticking time bomb. That’s the whole engine of the story, is that our hero is chained up in this room and a giant fire is coming. But nobody tells us how long it will be. At one point, I think two full days pass. It’s ridiculous. When you have a ticking time bomb – especially one as good as this – you need to keep updating your reader. The two captors need to have conversations like, “How long do we have?” “I don’t know. Maybe five hours?” Or heck, ask Kyle! He’s the expert on this stuff. Since I was never clear on when the fire would get here, I didn’t feel as much tension as I should’ve.

But this was a breezy read. It was a very good representation of what a spec script should be. 90 pages. Simple concept. Just a few characters. It’s easy for the reader to grasp what’s going on. I see so many specs die within ten pages because an overly complicated plot has been set up. Save those overly complicated plots for when you become a known writer. In the meantime, write for exhausted grouchy readers who don’t want to read another lame amateur script. Big simple concepts are your best bet at roping them in.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t expect your ticking time bomb to do the work for you. If the time allotted on your “bomb” isn’t clear, it will be up to you to periodically tell your audience how much time is left. How am I suppose to know how much time there was before this fire reached their house? One of the oldest screenwriting rules is apropos here – “We don’t know what you don’t tell us.”