Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: The wife of a megachurch pastor seeks atonement after she and her lover kill an attacker in self-defense, but don’t report it out of fear of exposing their affair.

About: This script finished number 12 on last year’s Black List. Andrew Zilch has been working in Hollywood since the early 2000s, where he was a crew member on Minority Report. He’s since moved onto producing television, where he’s been working steadily. Most recently he produced the show, “Good Mythical Morning with Rhett and Link.”

Writer: Andrew Zilch

Details: 119 pages

I love this setup. It’s simple but effective. Someone or a pair of people or a group of people kill someone and try to cover it up. But, since it’s a movie, the murder doesn’t go away, finding a way to creep back into their lives.

The only issue with the setup is that it doesn’t have the EXTRA. The EXTRA is that extra component that makes your movie bigger than the average bear. For example, let’s say you want to write a TV show about a family. Well that’s a pretty standard setup, isn’t it. There’s no EXTRA. But what if you made the family one of the richest in the world? That would allow you to explore the types of things that you don’t get to see in a typical family drama. “Succession” is currently one of the hottest shows on television. All because of the EXTRA.

Claire and Erik have rented an Air BnB cabin out in the middle of the wilderness so they can do fun adult things all weekend. But while they’re doing fun adult things, a man named Ronnie stumbles in, looking for something to steal. After grabbing Claire’s big diamond ring, he tries to sneak out, but runs into Erik, and that’s when all hell breaks loose. Confusion leads to a fight and Ronnie ends up falling down the stairs cracking his neck.

There’s no humpty-dumpty redemption for poor Ronnie. He’s dead.

Three months later we come to learn that Claire is married. But not to Erik. To Seth, a pastor at New Dawn Church, which is doing so well it’s about to sign a mega-deal with a TV station for broadcasting rights. We also learn that Erik buried Ronnie’s body on the lot and that, so far, nobody knows what happened to him. That changes within the first ten pages as the police announce that Ronnie’s body has been discovered.

In the article announcing the discovery, Claire learns that Ronnie had a daughter, Addie, which makes her feel insanely guilty. So she goes over to visit her under the pretense that she saw the story about Addie’s dad and wanted to see if New Dawn church could help in any way. While there, Claire meets Addie’s deadbeat boyfriend who knocked her up, Kyle, who happens to be an injured bull rider. Kyle and Claire dislike each other immediately.

While Claire’s friendship with Addie grows, Claire’s husband keeps pushing her to help him start a family. For some reason, Claire hasn’t been able to get pregnant (hint hint, she’s trying not to). Also, Erik keeps stopping by whenever Seth isn’t around to plead with Claire to get back together. During one of these talks, Kyle is sneaking around back and overhears them talk about killing Ronnie.

With newfound leverage, Kyle makes his demand. He wants 100k and he won’t tell anyone. Claire says I’ll do you one better. I’ll keep the church safe open tomorrow night and you can take everything that’s in there – over 200k. The only catch is you have to leave Addie alone. Kyle does just that, barely escaping. Claire believes all the drama is finally over. But when Kyle tells Claire that the woman who claims to be her new best friend killed her father, everything falls apart.

Like I said in the opening, you have to have a plan when you’re writing a script based on a concept that could be a five episode subplot in a soap opera. This is a MOVIE we’re talking about here. It’s got to be bigger than real life in some way. It’s gotta have the EXTRA. And the big question with Wayward is, does it have the EXTRA?

Here’s what Zilch did. He didn’t have just any woman cheat on her husband and keep a murder secret. He had the wife of a preacher do it. That elevates things quite a bit since we’re talking about some major irony there. Already, the setup feels juicier than your average “dead body” script.

From there, it’s about acing the two screenwriting mainstays – character and plot. In a high concept screenplay, you don’t have to write the greatest characters ever. Even your plotting can be sloppy because your concept is doing the heavy lifting. But when the concept is average, scripts like this don’t make the Black List unless the character work and plotting are exceptional.

I’ll tell you the exact moment I knew the writer was better than your average writer. It’s when Claire visits Addie and we meet Kyle for the first time. Note that Kyle was the 9th or 10th character introduced in the script. And we quickly learn, in that scene, that Kyle is a bull rider who recently got injured. Which is why he’s doing such a poor job caring for Addie. He’s not making any money.

It was the fact that a character introduced this late in the story had such a specific backstory that I knew I was in good hands. Cause the majority of the scripts I read, the writer doesn’t know anything outside of the immediate world of our hero. They couldn’t tell you what Boyfriend of Secondary Character #3 looks like, much less their job and how it’s affected their lives over the last six months.

I don’t run into a lot of writers who care to go that deep.

And some of you might be saying, “Who cares if this random dude is a bullfighter?” It’s not a pointless backstory. His desperation because he doesn’t have a job is why he wants to exploit this friendship that his girlfriend has with this rich woman. It drives the plot. But had the writer not gotten to know Kyle’s life, he may not have found this storyline. That’s the hidden gift of doing the extra work and finding out what every character’s life is like. New plot ideas pop up all the time when you do that stuff.

I did have a couple of problems with the script, though. And, unfortunately, they were big ones.

I didn’t buy into this idea that some guy was walking through rural Oklahoma, hoping to bump into a house where he could steal something. I mean what’s the steps per likelihood of target in that scenario? 800,000 steps for every one house that may be available to rob?

Normally, this wouldn’t bother me. But as I’ve stated before, the pillars of your plot need to be rock solid. If there is a plot development that is crucial to your story working, that plot development must be pristine. It can’t have anything in it that makes the audience say, “Wait a minute, hold on. He’s doing what?” Cause the second the audience starts asking questions like that, they become aware that they’re watching an artificially constructed story. And because this moment is setting up the entire movie, that means the question is going to linger the entire movie.

It wouldn’t matter if it was a nothing scene ten pages later. But this scene sets up the whole movie!

A similar problem happened later on. Kyle has the upper hand. He can literally tell the cops that Claire and Erik killed a man. So how is it that Claire gets to say, “Here’s the location of our church safe. Go steal the money from it.” Why does the person with the leverage have to perform the dangerous act? Any sane person would say, “Why don’t you get the money out and bring it to me?” And since this was also a major plot point, it hurt the final act.

Which is frustrating because there’s so much good here. All the characters pop. You’ve got this delicious dramatic irony dripping throughout, as Claire is befriending the daughter of the man she killed and pretending like everything is hunky Dorey with her pastor husband. You’ve got the raised stakes of an impending TV deal for the church, which ratchets up the tension with Seth, causing lots of head-butting with him and Claire. You’ve got fun little contrasts such as Seth being a devout Christian and Erik being a hardcore atheist.

I feel if you fixed those two pillar scenes that this script could easily be an “impressive.” But right now, it’s in that “worth the read” category, at least for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Give a little history in the description of the area your story takes place in. Here’s a description of the town in the script: “Once a rough-and-tumble frontier town, Ransom is now an upbeat Tulsa suburb.” Towns can have arcs just like characters. And a simple description of that arc gives the setting life. As opposed to if you just said, “An upbeat Tulsa suburb,” which elicits a much weaker image in the reader’s head.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: After a mission to destroy a black hole that endangers mankind goes wrong, an astronaut awakens in her escape pod to find that decades have passed seemingly in a moment. Now, with an old body and fragile mind, she battles against the elements of space & time to complete her mission.

About: This script finished in the Top 10 of last year’s Black List.

Writer: Nabil Chowdhary

Details: 84 pages

Today we have something special. It’s a Black List script from a writer who made his internet screenwriting debut right here on Scriptshadow with his very first screenplay. I went back and read my choppy review of that ghost script to learn that I liked the setup but felt the script took a dive in the second half.

But this is a documented roadmap for how to go from first screenplay to a Verve-repped Blacklist screenwriter in 4 years. And while that may seem like a long time to those new to the screenwriting trade, it’s a rare feat when a screenwriter can go from Beginner to Pro in under 5 years. Let’s take a look at what Chowdhary is up to with his latest script.

Clare wakes up in a pod in the middle of space. She doesn’t remember any event that led to this situation. Then Hex comes online (the ship’s nice version of “Hal”) and tells Clare she was on a mission to destroy the black hole that is quickly eating up the solar system.

Her and her team were sent out to Saturn to throw an anti-matter pill into the black hole, where, according to science, the matter and anti-matter would cancel each other out, and the black hole would disappear. But something went wrong along the way and Clare was spat out into space in her escape pod.

And there’s an unfortunate side effect to the event. Clare brushed up against the event horizon and, in the process, aged 30+ years. She’s now an old woman. It’s a real bummer when she finds this out but she doesn’t have time to dwell on it because Mary, from mission control, calls her, asking if their mission was a success. Uh no, Clare says. And I now look like Wilfred Brimley!

Mary tells Clare she’s going to set some coordinates for Clare to head to near Mars, where they’ll be able to remotely bring her back to earth. After hanging up on Mary, Hex brings up some questions about her, asking if Clare has ever even heard of her before. Clare agrees that, yes, there is something suspicious about Mary.

But she doesn’t have time for ’back at the house’ drama since her oxygen is running low. If she’s going to get that rose, she needs to hurry up! After navigating their way through our solar system’s asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars, Clare starts to realize she’s probably not going to make it out of this alive. Which means making amends with her mom in a video selfie.

But then Clare gets a distress call from a mysterious woman who may have also escaped from their old ship. Clare commands Hex to ditch this whole Mary return-to-earth project and head back to the scene of the crime, where that hungry black hole is still munching everything up. Hex reluctantly brings her to the distress call’s location, only to realize it’s actually INSIDE THE BLACK HOLE. To find out what’s going on, they’ll have to travel inside. What will happen to our space-faring heroine? Check out “Pod” to find out.

The first thing I noticed is that just like when Chowdhary started, he’s still going into his screenplays with a high concept idea. He knows that the most likely way to get noticed is to start with a strong concept.

High concept ideas DO NOT automatically mean better screenplays. There’s a strong argument to be made that the best screenwriting comes in the lower-concept variety. But the reason high concept is still the better choice is that you’re getting more people requesting high concepts than low ones. And in a numbers game business you want to buy as many lottery tickets as you can. It’s not hard to do the math. 20 out of 100 script requests is going to yield a higher return than 2 out of 100 script requests.

I can’t emphasize this enough. I get so many writers coming to me complaining that they aren’t getting enough requests from their queries. I then ask them their concept and they say, “Oh, it’s a drama about friends trying to become actors in LA” or something like that. I mean, come on. You’re really surprised people aren’t requesting that?

I also noticed that Chowdhary has become more focused. This is a big key for screenwriters – learning that good storytelling isn’t following whatever whim pops into your head while you’re writing. That can be a valuable experiment, don’t get me wrong. It’s important to try a bunch of things early in your career to see what you’re good at and what works. But as you get better, start telling a tighter story with a strong focused narrative. “Pod” is definitely that.

Double finally, you’ve got a super cheap sci-fi project to shoot. And you’ve got a compelling mystery at the heart of your story. What happened that sent Clare’s pod shooting out of that ship? We want to know so we keep turning the pages.

But I struggled with Pod in two areas. The first is in the “obstacle” department. I read a lot more “isolated in space” scripts than you’d think. My guess as to why there are a lot of these scripts is because there are a lot of people who want to make their 2001. And the mistake a lot of them make is that the obstacles facing our hero are ones we’ve already seen.

You’ve got the oxygen running low trope. You’ve got the asteroid field trope. You’ve got the AI entity to give your hero someone to talk to. Just like we were talking about yesterday with garden variety suspect questioning scenes in procedurals, stuck in space movies always have these “been here already” plot points that are called upon again and again.

On top of that, I didn’t understand the flight capabilities of this pod. From what I could gather, it’s barely bigger than the person inside of it. But it has the power to travel around the solar system within a matter of minutes. I suppose this is an unknown future where, conceivably, major technological breakthroughs could have created something like this. But to travel from Jupiter to Mars in minutes? That was a tough buy.

There are two kinds of sci-fi out there. There’s broad sci-fi which is basically fantasy. And then there’s hard sci-fi, where the writers are careful about making everything seem plausible. Star Wars is broad sci-fi. Ad Astra is hard sci-fi. Where you’re going to confuse your reader is when you stuff both of these types of sci-fi into a single script. And that’s what’s happened here. This pod the size of my couch can travel from the sun to Jupiter in minutes?

With that said, I give Chowdhary props for creating a fresh contained thriller in the hardest genre to create reasonably budgeted stories in. He essentially asks, “What if you made Buried in space… and then added a killer black hole?” – And Chowdhary has come a long way with his writing. This script felt a lot more confident. As opposed to his first script, which had a “making things up as I go along” feel to it. This was a better script overall, but didn’t quite reach “worth the read” territory due to the problems I mentioned above.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There are some tropes that are so popular, you assume they need to be a part of your story. So if someone’s up in a space ship and something goes wrong, one of the first ideas that’s going to come into your head is that oxygen should be running low. I’m not claiming you should never use this plot development. But do you really want to use something that audiences have seen in 200 plus movies and TV shows? Obstacles are just like any creation in a script. The more unique they are, the more they’re going to help your script stand out.

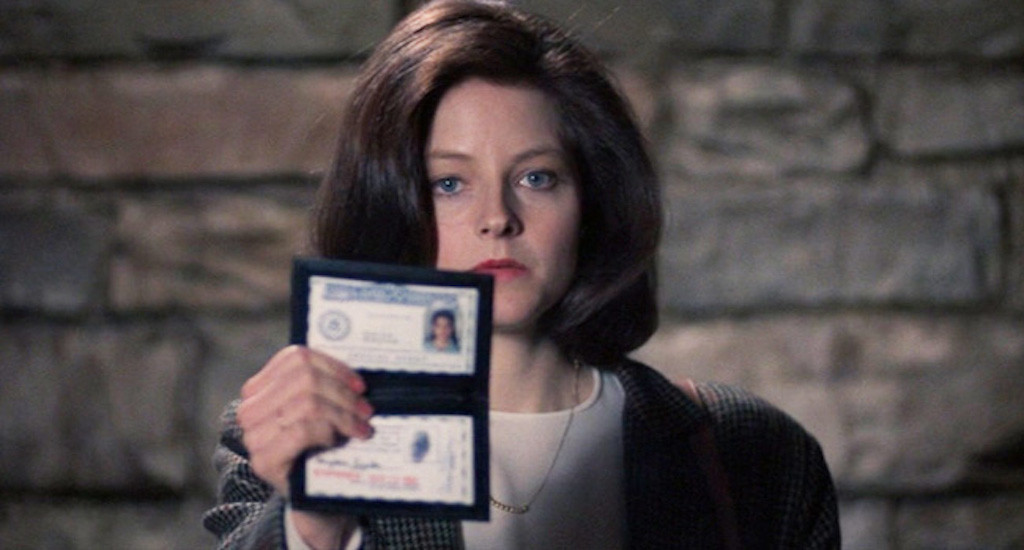

Clarice Starling is back! And can someone tell me what the heck Conflict Coffee is??

Genre: 1 Hour Drama

Premise: The continuing exploits of FBI behavioral specialist Clarice Starling one year after the famous case that made her a celebrity.

About: The first attempt at creating a Clarice TV series happened back in 2012, around the same time when that Hannibal series went to air. But the show never made it. This time, the project is being spearheaded by hardest-working-writer in the business Alex Kurtzman and “Rachel Getting Married” screenwriter Jenny Lumet. CBS is said to be big on the show and are expecting it to be a breakout hit.

Writers: Alex Kurtzman & Jenny Lumet

Details: 63 pages

Writing a script like this isn’t that different from writing a spec as an unknown. As an unknown, people go into your script assuming it’s going to be bad. So it’s up to you to prove them wrong. And the sooner you start proving them wrong, the better. Because readers are looking to confirm their bias. As soon as they can CONFIRM it’s bad, they can start skimming.

Writing a Clarice Starling pilot is similar. Viewers are going into it rolling their eyes. It feels like a cash-grab, an exploitation of a perfect movie following a character nobody is interested in seeing outside of those films. So you have to prove them wrong. And the sooner, the better. Because viewers have lots of other options. And they’re not waiting around to see if a bad idea gets better.

With that said, it’s not impossible to write a good Clarice pilot. Everyone thought the same thing about the Fargo TV show. You’re exploiting a perfect movie that isn’t asking to be fit into the TV format. But, what do you know, it turned out great and launched Noah Hawley’s career. Will this have similar success? I’ma let you know in a minute.

It’s been a year since Clarice came out of Buffalo Bill’s house of horrors with Catherine Martin and things are a lot different. Clarice is struggling to deal with the fame and the FBI’s head therapist isn’t convinced she should still be working. Clarice still hasn’t talked to Catherine since that day and the therapist thinks it’s because she still hasn’t processed what happened.

Then Clarice gets a surprise call from Attorney General Ruth Martin. Ruth Martin as in, yes, Catherine Martin’s mother. She flies Clarice to D.C. and tells her they’ve got two young dead women with bite marks on them who have turned up in the river. Ruth thinks it’s a serial killer and she wants Clarice on the case. But Clarice is still barely an agent (it’s 1993 and she’s just 26 years old). So she’ll have to answer to Task Force head Paul Krendler, who doesn’t like Clarice and her lucky serial killer capture one bit.

Immediately, Clarice and Paul disagree on what’s happened. The bite marks indicate a single killer. But Clarice’s training tells her there’s something odd about the bite marks. They aren’t… sexual, which was the operating thesis before Clarice showed up. There’s something weird going on here. But Paul doesn’t want to hear it, and forces Clarice to tell the media it’s a single killer.

Clarice, ever the friend to the freak shows and the misfits, befriends loner detective Tomas Esquivel, a Cuban American who’s still mad at the task force for hazing him by putting beans in his locker. The two go off and talk to family members of the victims, eventually learning that all of them have ties to autistic children.

Clarice begins putting together a working thesis that the women in the river were whistle blowers for a biolab company dabbling in autism medicine. What this means is that this isn’t a killer doing this. It’s a company. Which means this is much much bigger than anything she’s investigated before.

I’ll start by saying this. Sequels are always better than prequels and here’s why. The objective in writing any fictional story, particularly movies, is that you want this event you’re writing about to be the biggest moment in this person’s life so far. If it isn’t, then you’re telling the wrong story.

Luke Skywalker didn’t do anything interesting growing up. Which is why we don’t tell any of that story, as much as Disney would like to. Luke’s life only got interesting when that message from the princess showed up.

Same thing with Clarice. I was worried that they were going to do a Silence of the Lambs prequel with this show. Which would imply that Clarice had a bigger moment in her life than taking down Buffalo Bill. So I’m at least happy that they decided to set the events of “Clarice” after Silence of the Lambs.

But this is an auspicious start to the show. I get what they’re doing injecting some big bad government conspiracy into the mix as to generate enough of an overarching storyline to fill up an entire season. But I’m not sure that an autism conspiracy ignites my reading motor. I mean this is the franchise that gave us Buffalo Bill and Hannibal Lecter. It feels like a step down.

And I’ll give you the exact moment in the pilot where I said to myself, “Uh-oh.” It occurs when Clarice and Esquivel go to the victim’s husband’s house to ask him questions. They go there, ask if they can come in and ask him questions, he says yes, and they come in and ask questions.

Why is this a problem scene for me? Because procedurals have been around for 100+ years. That means you have to always be on your game to keep them fresh. One of the laziest ways you can write an agent-suspect questioning scene is to have them come to the suspect’s house and, in a perfect setting, ask them questions. It’s such a lazy setup that the scene dies before it’s written. You’ve already chosen the least interesting way to tell this scene so, chances are, it’s going to be weak.

I’m not saying you can never write a procedural scene in a character’s home. But it has to be under the pretense that you understand this is a boring way to explore the scene. Therefore, you’re going to do something with it that uses that expectation against the reader. For example, if the suspect is the husband of the dead wife, as is the case here, they show up and he’s extremely chipper. He’s upbeat, happy, asking how they’re doing. Not acting like someone who just lost their wife at all. At that point, we forget where we are because we’re so focused on this character’s odd behavior.

But my preference is that you don’t send your hero to a garden-variety house questioning scene at all, ESPECIALLY when it’s the very first suspect visit of the series. A great hack for avoiding this mistake is to ask, “What’s the worst situation under which my detective would want to question this person?” And then write the scene under those conditions.

It could be as simple as them catching him leaving work during a huge storm. They corner him right as he’s about to get in his car, rain pounding, he says he’s late and has to go before finally saying he’ll give them two minutes. Right there with the rain assaulting their umbrellas, they must hurry up and ask him what they need to know. I guarantee you that’s going to be a better scene than if you sit down with the suspect in his quiet home with all the time in the world.

The best thing this pilot does is the conflict between Clarice and Paul. He really dislikes her. Not just that, but he feels like she didn’t earn this promotion. That she doesn’t belong in his presence, on this case. That created a desire in me to see Clarice prove him wrong. And, actually, that was the only drive for me to finish the story. I wanted her to make this guy look like the loser he was. Unfortunately, everything else was too generic. I felt like I’d seen this show before. The fact that this is Clarice instead of some no-name did help a little. But once the excitement of that died down, the show had to work on its own. And it didn’t work for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Brew your conflict coffee under every scene. What’s conflict coffee? It’s the coffee you brew under a scene before the scene starts that allows for conflict to play out. Most writers don’t brew conflict coffee under their scene. They just plant characters in a generic room with nothing else going on and let them talk to each other, then are confused when everyone says their scenes are boring. Your scenes are boring because you didn’t brew any conflict coffee underneath them!!! Take the suggested scene I created above in the rain. I brewed three heavy cups of conflict coffee under that scene. The first was the storm. That makes things difficult for our heroes. The second is a suspect who doesn’t want to talk to them. And the third is he’s in a hurry, he’s got to get home, so he only has time for a few questions. Imagine the scene WITHOUT those three cups of conflict coffee and then WITH those three cups of conflict coffee. Now tell me which is more likely to be the better scene.

It’s the WWEEEEEEKKKK-EEEENNNND.

Which means we’ve got THREE new movies being offered up at the cinemas. And it just so happens these three films give us the perfect snapshot of what the industry is looking for. We’ve got Gretel & Hansel – our horror movie. We’ve got The Rhythm Section – our Jane Wick flick. And we’ve got The Assistant – our socially conscious entry of the week. All three films, it should be noted, have female leads.

While none of these movies will do huge box office, this is the kind of stuff that Hollywood is looking for from spec screenwriters. The Jane Wick flick might be on the way out, especially if Rhythm Section doesn’t do well. But with the well-written “Ballerina” coming soon under the John Wick banner and therefore with a ton of those Wick marketing dollars, the Girl with a Gun genre might not be dead yet.

What are your thoughts on this weekend’s crop of films?

Let’s move on to Amateur Showdown. Is it ever coming back? Or is it DEAD? Let’s find out together, shall we? On March 13th, we will have SCI-FI SHOWDOWN. My favorite genre. Or wait, wasn’t contained thriller my favorite genre? Who cares. Sci-fi is my favorite genre now.

This gives you 43 days to get your s%#@ together and polish that sci-fi gem you’ve been tirelessly working on for the last six years. Oh wait, that’s me. We’re talking about you guys. Yes, starting today, you can send in your script for Sci-Fi Showdown. Just e-mail carsonreeves3@gmail.com and put “SCI-FI SHOWDOWN” in the subject line. Include the title, genre, logline, why you think the script deserves a shot, and, of course, a PDF of the script. You’d be surprised at how many people send me entries with no script. You have until Thursday March 12th, 8:00 PM pacific time to get your entries in.

And, if you’re still getting that Last Great Screenplay Contest script ready, a reminder that the deadline is Sunday, June 14th. I need the title, genre, logline, and PDF sent to the same e-mail (carsonreeves3@gmail.com). Except the subject line should be: “LAST GREAT CONTEST.”

Meanwhile, for those who’ve got time to waste, let’s talk about The Outsider. If you haven’t been on the site for a while, I gave a glowing review to the first couple of episodes of this show. I liked it so much, I thought I was watching one of the great TV shows of all time.

Two weeks later I find myself struggling to finish Episode 4. Welcome to the challenge of TV writing, where great television can nosedive in as few as two episodes. So what happened to The Outsider? I’m not sure. But I can tell you exactly when I sensed it was in trouble.

It came in episode 3 with the introduction of a new character named Holly Gibney, a private investigator. Since this character is so all over the place, I’ll leave it to the Stephen King wiki webpage to describe her: “Holly suffers from OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder), synesthesia, sensory processing disorder, and she’s somewhere on the autism spectrum.” In other words, she’s a “LOOK AT ME AND HOW WILD AND WACKY AND DIFFERENT I AM” character, one of the worst characters a writer can write.

Up until this point, the reason The Outsider was so good, outside of the fact that it had a great hook, was that it had embedded itself in authenticity. These felt like real people. This felt like a real town. These felt like real consequences. This felt like real mourning.

By writing in a totally unrealistic desperate attempt at a scene-stealing character, all that authenticity went out the window. We now had a WRITER (notice the capitalization) who wanted us to know he was WRITING. It doesn’t help that the actress is awful, but the important thing to note here is that, before, characters were authentic. I mean who’s more believable as a person than Detective Ralph Anderson? Holly Gibney might as well be in the next Bad Moms sequel (Bad Moms “Easter Shenanigans!”) she’s so outlandish and unrealistic.

It doesn’t matter what you’re writing or how good it is. The second you start writing to impress the reader – whether it’s with your purple prose or outlandish plot twists or crazy characters – you lose. Because that’s the moment when the reader or viewer becomes aware that someone is writing this. And that’s when you’ve lost your audience, when they’re no longer suspended in disbelief. I wouldn’t say that Holly Gibney single-handedly ruined this show. But it’s hard to stay invested in a show when you’re rolling your eyes half the time.

I’m going to keep trying though. Ben Mendelsohn is such a good actor that it’s worth continuing to watch just for his scenes. I mean what other actor could’ve made Captain Marvel watchable? But I’m worried. I’m going to pray this Holly abomination gets knocked off at some point. And that they can ramp up the mystery again. There were full loaves of mystery early on. Now they’re trickling little breadcrumbs at us and expecting us to clap like dolphins.

What do you guys think? Am I being too hard on it? What’s your take on the last few episodes?

Lonestarr357 had a great question in yesterday’s comments. After Scott S. eviscerated the uncomfortably detailed opening scene of I Heart Murder, Lonestarr asked this:

I’m unmistakably reminded of a script from a couple months ago and the indelible scene where the investigating hero was caught, paralyzed and fellated by the villains, who told him to back off or they would not only kill his daughter, but deposit the sperm they just extracted inside of her, so it’d look like he raped her before killing her.

I feel like this ought to be an article in the making. We’re told to create memorable scenes to get the attention of readers, but how far is too far? Does the reaction you hope to elicit fall more toward ‘This is a memorable scene! Let’s give the writer lots of money!’ or ‘This is a memorable scene. I need a fucking shower?’

This is a great question.

I know it’s a great question because as soon as I began typing up my response, I realized I didn’t know the answer. I thought I knew. But this is a far more complex question than it first appears to be.

I remember the exact scene Lonestarr is referring to. And I thought the same thing he did when I read it. This is way too far. It’s uncomfortable. It’s a weird choice. And yet, I DO REMEMBER it. I’ve read thousands of scenes since then and have forgotten almost all of them in the process. But I do remember that scene. So does that mean the scene is a success? You must be doing something right if your scene is more memorable than two thousand others, right?

This leads us to a broader question of, “What makes a memorable scene?”

Strangely, when I tried to compile a list of standout scenes over the last few years, not a lot came to mind. I even googled, “Most memorable scenes of 2019,” and a lot of the scenes they listed were okay. But I wouldn’t call them TRULY MEMORABLE STANDOUT SCENES.

A few that people seem to agree on were The Spahn Ranch scene in Once Upon A Time in Hollywood. The Baby Delivery scene in A Quiet Place. The Birthday Party at the end of Parasite. And The Beheading scene in Hereditary. Some of my personal favorites over the last few years would be the Pennywise sewer scene at the beginning of It. The failed Deadpool Team attack in Deadpool 2. And the highway border shootout in Sicario.

What do almost all of these scenes have in common? They’re SPECIFIC TO THEIR SUBJECT MATTER. The Spahn Ranch was Charles’ Manson’s spot in a movie where Charles’ Manson’s shadow is leaning over the whole movie. It made sense to set a major scene there.

What’s the worst thing you can put your characters through in a world where you can’t make a noise or you die? Force a woman to have a baby under those circumstances. A Quiet Place.

Parasite had been setting up the son’s infatuation with Native Americans the whole movie. So it was only natural to have a Native American themed birthday party that all of a sudden becomes violent and murderous.

What’s more “super heroey” than trying to put a new superhero team together. Hence a superhero interview process that ends with six heroes going after the bad guys, only for all of them to die horrible embarrassing deaths, was very specific to that genre.

When you have a movie about a clown who lives in the sewers who likes to eat children, you probably want to write a featured scene where a clown in a sewer lures a young boy in so he can eat him.

The best way to understand the power of writing a scene specific to your subject matter is to see what happens when a movie TRIES to write a memorable scene and fails. Look no further than the motorcycle chase scene in Gemini Man. Now this isn’t a bad scene. But it’s far from a memorable one. Chances are you’ll forget the details of it within 48 hours.

While I’m not saying a lack of specific subject matter is the only reason the scene is memorable, it is a major one. WE’VE SEEN MOTORCYCLE CHASES BEFORE. We just saw one in John Wick 3. And that one had freaking samurai swords. Yet you’re here trying to make a nuts and bolts motorcycle chase scene your big memorable scene of the movie? Of course it’s going to be forgotten. And the big reason for that is that motorcycle chases are a dime a dozen in action movies. You needed to come up with a scene that was SPECIFIC TO YOUR SUBJECT MATTER.

So let’s go back to Lonestarr’s original question. What is it about that fellatio sister rape-framing scene that, even though it *is* memorable, doesn’t place it in the same category as the scenes I highlighted above?

The main problem is you’re introducing SHOCK for shock’s sake. A truly shocking moment *will* be memorable. For example, I could have a character butcher a live elephant over the course of five minutes. It would be shocking. It would be memorable. But would it be the good kind of memorable? No, of course not.

These scenes also become a problem when the writer makes it more about them than the story. Again, if you look at all of the examples I used above, those scenes organically fit into the story. But when you’re having characters say and do things that are utterly disgusting and way further than they need to go, that gives off the impression that the writer is trying hard to make his scene shocking. And in those cases, it’s more about them than the story.

But that brings us to the curious case of Hereditary. As some of you remember, I hated Hereditary’s script. I thought it was the epitome of desperate shock-value writing. There’s no movie here. It’s just a collection of “look at me” shocking moments. And no moment was more “look at me” and shocking than the sister decapitation scene.

However, in director Ari Aster’s defense, it’s legitimately in the top 5 most memorable scenes of 2018. Many Hereditary fans will use it as proof positive of Aster’s genius. But this is a scene that does not pass the SPECIFIC TO ITS SUBJECT MATTER test. You could’ve written this scene into any horror film of 2018 without much story rearranging.

So that’s what’s tripping me up on creating a clear set of rules regarding MEMORABLE GOOD scenes and MEMORABLE BAD scenes. Clearly it’s in the eye of the beholder. However, I do think that focusing on creating a big clever well-set-up scene that’s specific to your subject matter is always going to yield better results than writing a shocking or vile or uncomfortable scene. Those will be memorable. But for all the wrong reasons.