Last week, The Sun Ghost ran away with Amateur Showdown. I was supposed to review it today, but as I started reading it, I realized that I was rushing, and this isn’t your typical Amateur Friday entry. I could tell that the writer put a ton of work into it and I didn’t feel like I was giving it its just due. I have a lot of work to do over the next three days so I’m going to postpone the review until next Friday.

But don’t be sad. Sunday night you get a Scriptshadow Newsletter where I review a script from one of my favorite screenwriters, Monday is Avengers: Endgame review, and Tuesday is Cobra Kai Season 2 review. So there’s a lot of fun coming up. If you’re not already on my mailing lis, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER.” Enjoy your weekend!

Today’s article is dedicated to Steph, who’s been struggling to gain traction with her “two old ladies stuck on an island” screenplay.

As she’s said herself, something about the idea isn’t popping enough to get people interested. And so I asked the obvious question. Why? What is it about this idea that isn’t working?

To me, it comes down to a hook. There’s nothing in the idea that’s hooking me. But then I thought of some other movies that have been successful, movies that arguably didn’t have a hook either. Did Bridesmaids have a hook? The pitch for that movie is: “Bridesmaids being catty.” That’s not a hook. Yet it made a boatload of money and even got an Oscar nomination!

This necessitated today’s question. What is a hook? As well as a follow-up question. Does having one matter?

In looking back through recent hit movies over the years, and in examining the myriad of ways in which those ideas were appealing, I came to the conclusion that there wasn’t a one-size-fits-all definition for a hook. But I did find some patterns.

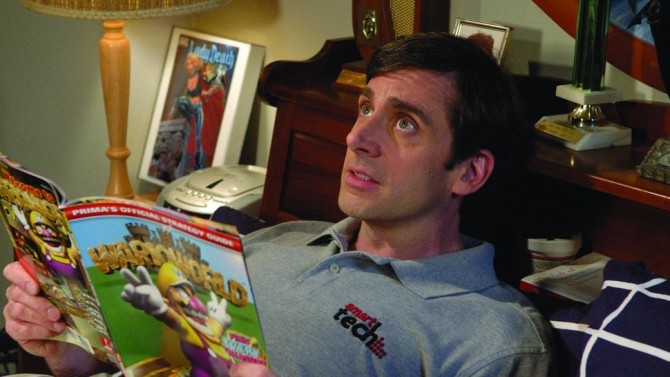

The biggest factor in determining a good hook is heavy contrast. Take The 40 Year Old Virgin, a movie with a hook so strong, you could sell it in the title. Let’s say that movie was renamed “The 17 Year Old Virgin.” Do you notice how quickly that idea went from “I’ve got to see that,” to “So what?”

That’s because there’s no contrast in the two elements. There are hundreds of millions of 17 year old virgins and therefore nothing unique about their situation. But when you’re 40 years old, you’re not supposed to be a virgin anymore. The contrast between those elements is heavy.

Since Steph’s idea follows a couple of older folks, let’s look at the number one movie on Itunes right now, which stars everybody’s favorite 80-something actor, Clint Eastwood. That film follows an old man who needs money and therefore agrees to be a drug mule. Drug-running is a young man’s game. There’s a high level of a contrast, then, in making our mule an 80 year old.

Let’s go back a bit further in time for our next concept, as it also shares some DNA with Steph’s idea. Lord of the Flies. A group of boys get stuck on an island and start warring against one another. To understand why this is a hook, all we need to do is substitute our kids for adults. “A group of men get stuck on an island and start warring against one another.” That setup is painfully obvious. The main elements, “men” and “war,” have been synonymous with one another since the dawn of time. By changing “men” to “boys,” you create a strong level of contrast. Innocent little kids aren’t supposed to war. Hence, you have your hook.

When looking at Steph’s idea, I’m struggling to find any contrast. I suggested to Steph that even if she changed one of the characters to a young man, the idea becomes more appealing because at least, then, you have contrast between the characters. But even then, there isn’t enough contrast to constitute a hook. That’s the trick with creating a hook. The contrast has to be overt enough to grab people’s attention.

But contrast isn’t the only way to create a hook. Where’s the contrast in Alien? Where’s the contrast in The Hangover? In these movies, a different kind of hook emerges. What is it?

With The Hangover, the hook is less about contrast and more about finding a unique way into a familiar scenario. We’d seen men going crazy at bachelor parties before. But we hadn’t seen a movie strictly about the day after, where the bachelors couldn’t remember anything yet must solve a mystery. With that said, there still needs to be an element of cleverness to the concept. If the pitch was, “A movie that focuses on a bachelor party before the bachelors go out for their big night on the town,” well, sure, that’s a unique way to explore the bachelor party setup, but there certainly isn’t anything clever about the idea, and hence it falls flat.

Any scenario that feels too familiar will fail to hook an audience. Ron Howard directed one of the blandest concepts I’ve ever come across. It was called “The Dilemma” and it was about a man who discovers his best friend’s wife is having an affair. The “dilemma” is whether he should tell his friend or not. Since there are hundreds of millions of instances in history where people cheat on their spouses, the idea was simply too familiar to be a hook.

Another common factor I see in a lot of good hooks is high stakes. The idea feels like it matters. In two of the concepts I’ve highlighted above, The Hangover and Lord of the Flies, the stakes are sky-high. In one, the wedding, as well as the groom’s life, are on the line. And in Flies, little kids’ lives are on the line. The stakes even feel high in The 40 Year old Virgin. If he doesn’t get laid with the help of these guys, he may die a virgin.

So what about Alien? Where’s the hook there?

This one had me miffed. There’s no contrast. The idea wasn’t exactly clever. What’s the hook? Then it hit me. In 1979, when that movie came out, it was a unique scenario. People stuck in a spaceship with a killer alien hunting them down. That’s one of the primary directives of a good idea – You want a combination location and threat that we haven’t seen together before.

Finally, you want an inherent sense of conflict in your idea. The more conflict within the idea, the harder it’s going to land. The Martian. A man who must live off a dead planet while he waits for a year to be rescued. The conflict between man and planet is extreme. It is a completely unforgiving place.

Which brings me back to Steph’s idea. There isn’t enough conflict to get me excited about the scenario. I suppose there are stakes in that they have to get off the island or they die? But I’m failing to see anything unique or exciting about what happens in the meantime.

Despite all of this, I still find that there’s a level of gray when it comes to hooks. What hooks one person doesn’t always hook the next person. I still don’t know what the hook to Bridesmaids is. Which tells me that a hook isn’t required to write a successful screenplay. But it does give you a huge advantage. There’s nothing quite like having an idea that speaks for itself, that you don’t have to convince people of. So I’d recommend everybody, especially unknown amateur screenwriters, write screenplays with strong hooks.

I’d also love to hear your thoughts on what you think makes a good hook. Maybe we can use Steph’s idea as a discussion point and, ultimately, help her find a hook for her movie.

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise: When a high school girl writes that her father is dead to win a scholarship essay contest, her father likes the idea so much that he decides to fake his death so he can start a new life.

About: This is Amanda Idoko’s second trip to the Black List. In 2017, she wrote a script called “Breaking News in Yuba County,” about a woman who pretends her husband is missing after he collapses of a heart attack in order to soak up in the celebrity status of having a missing loved one. Getting a second script on the Black List combined with studio initiatives to get as many female writers on the payroll as possible, Idoko landed the coveted assignment of writing the Plastic Man movie for Warner Brothers. Plastic Man, as many Hollywood aficionados know, has been in development for over 30 years. The Wachowskis famously wrote a draft of the script in 1995. Come to think of it, I’ve been meaning to review that script. Does anyone have it? If so, send it along.

Writer: Amanda Idoko

Details: 119 pages

Amanda Idoko is really obsessed with fake death scenarios. Or I guess the last one was a real death scenario that had been faked to be a missing person story. Either way, Idoko likes this setup.

The question I have is, why would anyone read these two scripts and think, “We’ve got our Plastic Man writer?” They’re dark comedies. Plastic Man is a goofy comic book movie. Maybe her pitch was that Plastic Man faked his death? “We love it!” If anything, they should be on this girl to write that whole college admissions scandal thing, right?

Frankie is Juno.

I mean, we can write up a big backstory for her but, let’s be honest. From her wise fast-talking persona to having a beta boyfriend who’s too in love with her, Frankie is Juno with a new name. At least Frankie’s not pregnant. Not yet, anyway.

All Frankie cares about is getting out of her stupid small town. And because her parents are losers, her only shot at this is winning the Harvey Scholarship. According to Frankie’s high school counselor, the Harveys love sad depressing stories. The light bulb goes off for Frankie. She’ll say her dad died!

Speaking of her dad, JP, he’s currently trying to divorce her mom, Liv, so he can marry his new girlfriend, Gina. This is yet another reason Juno, I mean Frankie, wants to get as far away from this place as possible. JP is resistant to the idea at first, but then learns about GoFundme pages for funerals, which can fetch up to 20 grand. If he goes along with this being dead thing, he can make a pretty penny and get out of this podunk town with his new beau.

But to pull this off, they’re going to need a body. Lucky for them, there was a mystery hero who recently ran into a burning building to save an old woman then, in going back to save her dog, was killed in the fire. Since he’s burned beyond recognition, it’ll be easy to claim him as JP’s body. Of course, that would make JP the hero, but they’ll figure that mess out later.

Immediately after that part of the con is executed, the old woman who was saved by “JP,” donates 200,000 dollars to his GoFundme funeral page! Liv, who’s always wanted to be a real estate developer, lights up when she sees this. She takes the money and buys her first property behind JP’s back.

Things only get worse from there. After Frankie’s boyfriend confesses to Frankie’s rival, Natasha, who’s going after the same scholarship as Frankie, that this is all a big lie, she breaks up with him. So in order to win her back, he kills Natasha.

As things continue to spin out of control, Frankie notes the irony of the situation. The whole reason she wanted to leave this place was because it was the most boring town on earth. But in one week, she’s had more excitement than most people have in a lifetime. Unfortunately, it’s too late to change course. Frankie made this bed. Now she has to lie in it.

A long time ago – 15 years at least – I had this idea about a UCLA college freshman who had the same name as the school’s big quarterback recruit. When that recruit doesn’t show up, our hero is mistaken for him. Loving the new celebrity status he’s acquired, he tries to keep the con going for as long as possible, despite the fact that he knows nothing about football.

But I could never make the script work because there was no believable scenario under which someone wouldn’t know what the real quarterback looked like. And that was 15 years ago. Can you imagine pitching that idea today? The quarterback would have an entire social media following. He would have dozens of Youtube videos showing off his amazing passes. He’d be a google search away from having 100 pictures of his face.

That’s what I was thinking about when reading this.

In a world this social media prevalent, how does a father in a suburb fake his death? It would be impossible. A 70 year old hermit without a family who’s never used the internet before who lives out in Joshua Tree? Yeah, maybe I can buy him faking his death in 2019. But a family man with an internet history and friends and extended family… I don’t know how that would work unless you moved to a Pacific Island or something.

I think a lot of older writers are in denial about this stuff. They want it to be like the old days where you might not hear from someone for a week and it wasn’t a big deal. But today, the world knows where you are every single minute. Literally. Whether it be from logging onto your phone, posting a picture, tweeting, using your credit card. Even your car is connected to a server somewhere, feeding you GPS coordinates.

In Idoko’s defense, suspension of disbelief is a sliding scale, and that scale gets more forgiving the further into the comedy sub-genres you go. Would two guys delivering a suitcase to a woman halfway across the country really buy a Lamborghini from the money they discover inside of it, as was the case in the movie, Dumb and Dumber? I’m guessing, no. But I never thought about that when I was watching it. I was too busy laughing.

I suppose that’s our answer when it comes to this conundrum. As long as the story is good, we’re not going to obsess over questionable story logic. Indeed, once the story gets going and Idoko is juggling six to seven balls at once, you’re not thinking back to that shaky setup. But the setup has always been sacrosanct to me. That’s where the majority of the exposition and character setup is, all the stuff that can gum up a read. So if you can come out of that without me questioning anything, there’s a good chance I’m going to enjoy the rest of the screenplay.

Dead Dads Club is a story of two halves. The first half is Idoko fighting with everything she’s got to make this setup believable. Then, after she’s done all the hard work and the game can be played, it’s actually quite clever. I loved the mom buying the house with the GoFundme money, completely disregarding the fact that all of it was for the dad, then the old woman’s daughter coming in and demanding the money her mother donated back. You could just see this house of cards crumbling and you wanted to see it fall.

But after it was all over, it didn’t leave enough of an impression on me where I would say to someone, “You gotta read this.” And that’s the true test of whether a script is worth the read on Scriptshadow!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I know this is a weird and hard question to conceptualize, but I want you to try. In this exercise, you need to take yourself out of the equation. Your latest script wasn’t written by you. It was written by someone else. Now if you read that script, would you recommend it to someone else? Be honest. Because this is the crux of whether your script will gain traction in the industry or not – if people read it and want to tell someone else about it. I don’t think enough writers ask themselves this question when they start to write something. They assume it’s going to be good because they conceived of it. But if you can take yourself out of the equation and look at your idea objectively, you may save yourself a lot of time and heartache.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A highly publicized AMA session with an aging musician goes off the rails when a hacker starts revealing dark secrets from his past.

About: This script finished in the top 10 of last year’s Hit List. The writer, John Wikstrom, is a Florida State grad who has a couple of short films under his belt. Wikstrom is repped by one of the last big spec agents in Hollywood, David Boxerbaum.

Writer: John Wikstrom

Details: 105 pages

Praise the LOOOORRRD! A non-biopic. I feel like throwing a party.

One of the hardest things to do in screenwriting is to find an idea that nobody’s come up with yet. But doing so is not impossible. In fact, a quick way to circumvent the issue is to choose a subject that’s only recently been added to the public lexicon.

While AMAs aren’t rolled-off-the-assembly-line-yesterday new, they’re new to most people. And that makes them potential fodder for a movie. But can someone build an entire narrative around people asking questions? Let’s find out.

Margo is that rare Los Angeles publicist who’s actually sweet. That wholesome quality has made her popular with artists, and that popularity results in the Johnny Cash-esque David Dollar requesting that Margo personally direct his AMA (“Ask Me Anything”) on Reddit, where he’s promoting yet another greatest hits album.

Margo heads over to Davey’s enormous mansion in the hills and is immediately charmed by the 70 year old legend in spite of herself. Davey seems amused by this thing they’re doing. This is a man who came up in the old school era where you remained elusive and mysterious. Nowadays artists are sharing their latest bowel movement on Instagram. It’s all a bit confusing for an old man.

Margo tells him not to worry. She’ll take the reins. She’ll read off the most upvoted questions, he’ll answer them, and she’ll type. An hour of painless fun. And it is painless for awhile. Until a mystery user posts a picture of Davey’s old girlfriend, Elizabeth Kelly, with a black eye, and asks the question, “Did you beat her?” Margo tells Davey he doesn’t have to answer but he insists he has nothing to hide, and explains that Elizabeth was actually hurting herself back then, which was well documented.

The AMA gets back on track but then things get real. Someone posts all of Davey’s financial records as well as his entire e-mail inbox. And just as Margo prepares to end the AMA, a naked picture of her is posted. She gets a direct message informing her that there are more where that came from if she stops this AMA. They have no choice but to keep going.

Surprisingly, every accusation that the reddit users are able to dig up from Davey’s private files, he has a perfectly reasonable answer for. This only makes them more frantic, more determined to take him down. But what they don’t realize is that they can’t take Davey down. He hasn’t done anything wrong. Still, something about all this doesn’t seem right. But neither we nor Margo nor the Reddit users can figure out what it is. Is Davey hiding something? Or is he yet another victim of a society who will do anything to get their piece of flesh?

I have to say, this one kept me guessing.

And I’ll explain why.

I want everyone to imagine the version of this story that came into their head when they read the logline. It probably went something like this. A young female publicist goes to an older entertainer’s home for an AMA. A hacker comes into the AMA. He starts exposing #metoo’ish secrets from the musician’s past. Our musician character fights back, denies, tries to explain it away, cover his tracks, until finally the hacker exposes him as the evil predatory monster that he is. He even tries to assault our poor little heroine.

The fact that you would’ve written that version of the story is why this writer has moved into the professional ranks and you haven’t.

When you come up with an idea – especially an idea inspired by headlines, like this one – it is imperative you not give us the execution we’re expecting. One of the first things the professional screenwriter asks when they come up with an idea is, “What is the movie the audience expects me to write?” Once they have that locked down, they make sure they don’t write that movie.

That doesn’t mean they won’t include parts of that movie. In fact, it’s advantageous to do so. In order to use an audience’s expectations against them, you must start by leading them down a path they expect to be led down. However, the further into the woods you get, the more you should be veering off that path.

I don’t want to spoil this script since it has a lot of surprises, but I’ll say this. There’s a moment after the midpoint where you realize Davey is innocent of the charges these people are leveling against him. Once that reality hit, I had no idea where the story was going. I thought I knew. I thought for sure I was getting the obvious version of the story. The fact that Wikstrom didn’t give me that was awesome.

Another thing I admire about AMA is how big it seems for such a small movie. That’s really hard to do. When you’re writing a typical contained thriller, one of the limitations is that the story feels tiny. A home invasion thriller can be riveting. But it’s only ever a story about those people in that house. What’s cool about AMA is that despite it being a single location movie centered around two characters, it feels huge, because it’s playing out on a world stage. That’s a producer’s dream. To have a movie you can make for so little money that feels enormous.

These types of movies live and die on the dialogue and while I wouldn’t classify the dialogue here as great, it’s pretty good for a thriller. A key component to creating good dialogue is power dynamics. You want to set a power structure between the characters that has one person above the other. This allows for conflict and subtext. Margo has to be respectful, since she works for this person. Davey has enormous power in the dynamic as he’s a legend and knows he can do what he wants. It’s hard to convey exactly why this is important but if you can imagine, for a second, two characters who are on the same level conversing in this situation, you can deduce that their conversation wouldn’t be nearly as interesting as one with this much of a power tilt.

The only thing I didn’t like about the script was that it was hard to buy that this would happen. I’ll give it to Wikstrom that he made sure there were reasons at every turn for why the AMA had to keep going (Margo was being threatened with nude selfies if she quit). But I’m not sure the whole thing passes the smell test. It’s a bit ridiculous. With that said, it was highly entertaining ridiculousness.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The three E’s. Educate, Elevate, and Entertain. Use your story to educate people about something (#metoo). Elevate the idea above what the average writer would do with it (went in a different direction than what was expected). Entertain (package it as a contained thriller). A common mistake with a lot of writers is they only focus on the first two. In other words, they write an uber-serious morality thesis about where we are as a society. Never forget that the first two don’t mean anything without the last one.

Genre: TV – Zombie

Premise: A few weeks after a fierce zombie breakout, groups of people in a [previously] perfect suburban town come together to try and survive.

About: I’ve heard this is connected to the Z Nation zombie series? I don’t know anything about that show so I don’t know how closely the two are linked. But after a quick google search, this seems to be its own show trying to do its own things.

Creators: John Hyams, Karl Schaefer

Details: 8 Episode Series – Netflix

I kept going back and forth on whether I was going to review this show. But then last night I watched the best scene I’ve seen in a movie or TV show all year, and that put me over the top. I had to review it. I’ll get to what that scene was in a second, but first, let’s talk Black Summer.

In many ways, The Walking Dead has destroyed zombies. Not forever. They’ll come back again. But the show dominated the zombie narrative for over half a decade and, once the show went downhill, killed off any excitement for the 50 year old monster.

Naturally, for these reasons, I went into Black Summer skeptically. We’re going to be bouncing around with groups of characters holed up in temporary buildings while dealing with the occasional zombie attack? Umm, isn’t that called The Walking Dead?

But Black Summer makes a few key changes to the format. And while they may seem small individually, when you combine them together, they give us a show that definitely creates its own identity.

The show starts off with a tremendous opening scene. In it, we’re hovering over a quiet suburb in the middle of the day. We cut inside of a house to meet a father, mother, and daughter. They’re scrambling. Scared. The mother tells the daughter to hurry. They have to leave now.

We show them peeking out their door. The peek tells us something dangerous is out there, something predatory. Once they establish it’s safe to go, they start moving. And it’s here where we see everyone is coming out of their houses as well, all scared, all jogging. Jogging towards something. We don’t know what yet.

Finally, we see their destination. A military transport. They’re shuttling people out. However, the soldiers are checking everyone for something before they can get on. A disease? It’s hard to tell. Finally, a soldier exposes that our father character is injured. His gut is bleeding. The mom starts freaking out. Trying to explain that he’s okay. Meanwhile, the daughter has already passed through security. The squabble gets bigger. More people get involved. And now gunshots. And then the transports are leaving. The mother is screaming. She grabs her husband. They escape to a house. But it’s too late for him. He dies. And then he turns. And then she runs. Because if she doesn’t, she’ll be just like him.

That’s the beginning of Black Summer.

Eventually, the mother joins up with a group. A criminal masquerading as a soldier. A mute man. A cowardly hipster. And soon we learn what everyone’s so afraid of. Zombies. But these aren’t your moaning groaning Walking Dead zombies. These things are relentless. They’re sprinters. Can appear out of anywhere and be on top of you within seconds. You don’t get to line up the perfect headshot with these slow-pokes. You have to shoot frantically, never hitting your target where you want.

It was these two elements that got me hooked on the show.

Number one, Black Summer is not a series of scenes. It’s a series of STORIES. Each cut-scene is like its own mini-movie. We’ve talked about that before as a way to structure a screenplay, via eight miniature movies. And that’s the approach they take here. Each sequence has a title (“Drive,” “Nature Show,” “The Others,” “Follower.”). They’re not short, like your typical scene (2-3 minutes). They often go on for 5, 10, even 15 minutes.

They last longer because each sequence isn’t doing the typical boring TV show stuff like setting up characters and laying down exposition for later payoffs. Rather, they give you a story to watch. Things start building right away. There are already obstacles showing up. Even if you wanted to stop watching, you couldn’t. You have to find out what happens. And this goes on with each new sequence. It’s amazing.

Number two, the antagonists are actually dangerous. Don’t get me wrong. Traditional zombies can be scary. In fact, there’s nothing quite like a character stuck in a location where zombies are lumbering towards him/her from all sides. That slow impending realization that death is upon you is something no other horror monster can replicate. But the zombies in Black Summer are worthy adversaries for our heroes. If one spots you, even if they’re a block away, you better start running as fast as you can or you have no chance whatsoever. When your antagonists represent that level of fear, you’re going to have a lot of great scenes. And I say this as someone who reads a ton of horror and one of the main problems I run into is that the monsters aren’t scary enough. I don’t fear them. Go watch one zombie scene in Black Summer and tell me you’re not terrified of these things.

These two elements are what set us up for the scene I was referencing at the beginning of this post. It’s a 15 minute scene. It’s just two people. And there are four lines of dialogue in the entire scene. You can go watch it now if you have Netflix. It won’t spoil anything. Again, that’s the great thing about this show. It’s a series of short movies more than it is a continuing storyline. So lots of scenes can be enjoyed on their own. It’s Episode 4 (“Alone”) and it starts at the 19:45 second mark.

What’s so crazy about this scene working is that one defining rule I’ve always preached when it comes to chase scenes is that we have to care about the character in danger. We have to like them so that we root for their escape. Yet this character (Cowardly Hipster) was my least favorite character in the show. He was weak. He stayed in the background. He was a scaredy-cat. Not much to root for. But once this thing started chasing him, I’ve never wanted someone to escape as badly as I wanted him to. I think this goes to show how important it is to create a worthy antagonist – something that possesses a true essence of evil. If we’re scared enough of them, we will root for anything that’s pitted against them.

Another reason this scene works is the way that it’s shot. It’s basically one continuous shot. That makes us feel like we’re in the action. And, by proxy, that we’re the character. Maybe that was the filmmakers’ intention. It was never about making us care about this guy. He barely ever speaks in the show (that’s another cool thing about Black Summer – there is very little dialogue, it’s all minimalistic). Maybe it was about making him an avatar. We are him. We’re scared because if that zombie catches him, it’s us who dies.

I can’t say enough about this show. One final thought is that these directors asked the same question all us screenwriters should be asking when we write scripts. “How do I make this different?” Utilizing a mini-movie scene structure, relentless zombies, and long continuous shots that put us right in the action, Black Summer avoided that Walking Dead malaise. And in an age where that show gets more boring by the week, that’s a good thing.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It can be fun to delve into your mythology. You want to show your audience how deep you went to conceive of this universe. However, every story should be approached differently. While sometimes, explaining the mythology can heighten an experience (The Matrix), other times, it can burden it. What’s great about Black Summer is that we don’t know what’s going on. Neither do the characters. And it’s better that way because the unknown is always scarier than the known. Point being: Make sure that if you’re going to get into details of how your mythology works, it’s the right thing to do for the story. Black Summer proves sometimes the right thing is for the audience to know nothing.

What I learned 2: If you’re struggling with scene-writing, particularly with how to build tension in a scene, this is a great show to watch.