I received an interesting e-mail last week which I initially disregarded but couldn’t stop thinking about. It was a beginner screenwriter who said he’d been reading my site and others for the last three months in order to learn everything possible about screenwriting so that he could write a great screenplay his first time out. He wanted to know my thoughts on if that was possible.

If you’ve been screenwriting for any length of time, you’ve heard the old coda that your first script is going to be terrible. And, actually, that your first five scripts are going to be bad. My experience with this statement has been that it’s true. Screenwriting is a deceptively difficult skill to learn. It looks easy because you don’t have to write as many words as a novel. And everyone assumes that if they love movies, they can also write them.

What these people eventually find out is that there’s a mathematical component to screenwriting (seeing as movies need to be 2 hours long) that must be effortlessly intertwined with a creative side of screenwriting, and mixing these two elements naturally is challenging. And when you really get down in the trenches, you learn that a reader’s attention span is way shorter than you think it is. Which is why most people reading your script won’t even give you the courtesy of reading past page 1. Look no further than Amateur Showdown for that.

But I tried to look at this question from a unique point of view – one might say, a movie concept point of view. I’m given a classroom of 30 people who have never written a screenplay before. ONE of these writers MUST sell a screenplay within the next six months or I’m dropped in a vat of acid by the evil screenwriting super-villain, Juan Augustian. What would I tell these writers in order to best give myself a chance to live? Or maybe the more interesting question would be, do I think there’s any chance at all that I would live?

I’m going to wait til the end of this post to answer that question. And, in the meantime, I’m going to tell you what I would tell those 30 aspiring screenwriters.

The first thing you need to do is read five produced screenplays cover-to-cover, five purchased but not yet produced screenplays cover-to-cover, and five amateur screenplays cover-to-cover. This is mainly to familiarize yourself with the screenwriting format and to compare the differences between amateur and professional work. But also, it’s to track when the story has you captivated and when you’re bored. You want to write down, in detail, why you believe you’re feeling this way.

Say you’re on page 20 and you’re bored. Why. Is it because nothing exciting has happened yet? Or is it because you don’t like something about the main character? If so, what don’t you like about them? The more detail, the better. Are they a sad sack? Are they passive, always allowing life to dictate their actions? By doing this, you’re creating a roadmap for what to avoid when you’re writing your own hero.

I should note that most amateur screenwriters have never read five amateur screenplays cover to cover. Which is sad. It wasn’t until I started reading amateur screenplays that I realized how many of these terrible mistakes I was making in my own scripts. Honestly, it’s like seeing the Matrix of Screenwriting. The green code disappears and is replaced by total clarity. I would even encourage writers to read more than five amateur scripts. But you should read at least five.

After you’ve read all your screenplays, it’s time to come up with a concept. This is probably the most important thing you’ll do. Not just because a good concept gets people’s attention. But because a good concept gives your script a framework whereby it’s easier to write good scenes. Say you like dinosaurs. Well, the concept of visiting a dinosaur island in modern day has more potential than a concept about a paleontologist who’s trying to prove his theory that dinosaurs were almost as smart as humans. There’s a very specific reason for this. In the first example, you can imagine tons of good scenes. In the second, all the scenes you’re imagining revolve around research and writing and conversations with other people. Which means you’re going to have to move mountains to come up with entertaining scenarios. You’re writing a MOVIE so you want an idea that gets people imagining a great movie.

Next up, keep things as simple as possible. One of the hardest things for new writers to manage is too many characters and too much plot. You can see them struggling right there on the page as you’re reading it. To avoid this problem, keep your story simple so you have a reasonable chance of staying in control. No complicated timelines. No overwhelming character counts. No jumping to 50 different locations throughout the story. You want a story that’s manageable.

Now I want to be reasonable here. Every good story has one element that’s troublesome. For example, 500 Days of Summer. It jumps around in time a lot, which is something I’d ordinarily steer a new screenwriter away from. However, that’s what makes the concept fun. So you have to bend somewhere. But make sure that troublesome component is the only troublesome component. You’ll note that 500 Days of Summer, outside of the jumping around, is about two characters in a relationship and that’s it. So it’s still manageable. If the writers would’ve added four other relationships that were also jumping around, the script would’ve imploded.

An ideal concept for a first time writer would be something like Murder on the Orient Express. Yes, it has a fairly large character count. But it’s high concept and it takes place in a contained setting – a train. Also, the story engine does a lot of the work for you – someone’s been murdered and they need to figure out who the murderer is. When you have crystal clear concept like that, it’s easier to write the characters since you know what everybody is trying to do (solve the murder).

The next thing I would do is try to come up with a really interesting main character or secondary character. A great character is a screenwriter’s best deodorant against a sub-par story. That’s because if you write an interesting character, we’ll want to watch them through anything. They become the focus of our interest. Not so much the plot. Think Joker. Think Monster. Think Nightcrawler. Think Venom. Think Lizbeth Salender. Think Fight Club. As much as I gushed over “Yesterday” in the newsletter, one of the things that held it back from being great is the fact that all the characters were safe and normal. There wasn’t anybody truly interesting.

And I’ll make you this guarantee right now. If you have a good concept and an interesting main or secondary character, you will sell your script. Cause those are the two big ones. A producer’s eyes will light up because they know the movie is both marketable and can fetch a great actor.

A few of you may be calling me out on that. “Oh sure, Carson. I’ll just write an all-time great movie character. Awesome advice. I never thought of that.” Fair play. Seasoned screenwriters know that creating strong characters is one of the hardest things about screenwriting. So here’s a hack specifically designed for the new screenwriter. Think of someone you know personally, or who you’ve met in your life, who you’d consider an extremely interesting person. Then use them as the inspiration for your character. We’ve all met some wild people. Why not capitalize on that? Put them in a movie! It’s not as good as creating the character from the inside out, but it’s way better than some plain average Joe.

Finally, come up with an idea that does the work for you. That means give your character a clear goal. Make sure the goal has major consequences attached to it. And make sure there’s some immediacy to the story – what needs to happen needs to happen NOW. Not in three years, not in three months, not even in three weeks. Now! If you create a framework that follows these rules, your hero will always have something to do. “Nightcrawler” is a good example. Louis Bloom wants to become the best nightcrawler in the business. When you have a goal that’s this clearly stated, you’re never going to be confused about what happens next, because you only have to ask yourself one question: “What does Louis Bloom need to do to get closer to his goal?” That’s what I mean by coming up with a concept that does the work for you.

Do I think it’s possible to write a great screenplay the first time out? If you follow these rules and you have some real talent? You have a chance. It’s a small chance. Probably around 2-3%. But it’s better than every other beginner’s chance, which is somewhere around .00000001%. So it CAN be done. Will you do it? Let’s find out!

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from Hit List) A young teacher reunites with her reclusive, scientific genius grandfather for the first time at his isolated country estate, uncovering disturbing truths about her childhood.

About: Jay Russell focuses mostly on directing. He directed the firefighter movie, Ladder 49, with Joaquin Phoenix. He’s making a movie about Lou Gehrig called “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth.” But here he’s turning to writing-directing and doing so in the horror genre. He sold this project to Paramount. Akiva Goldsman’s Weed Road will produce. The script finished with 18 votes on the 2017 Hit List.

Writer: Jay Russell

Details: 118 pages

Just as I was putting this review together, I saw the news over at Deadline about “10-31,” a horror script that has been “much pursued” by everyone in Hollywood. It’s about a Halloween night that goes awry due to a message in a piece of candy. Horror director Eli Roth will helm the movie. This is what he said after reading the script: “Very rarely do you get a script that grabs you by the throat, holds you until the last page, and gives you nightmares after. I don’t want to reveal too much, but this is one of the best, scariest premises for a horror film that I have read in years.” You know when someone starts talking about a great spec, I have to read it. And since it’s Halloween Month, we absolutely have to get this reviewed. So if you have 10-31, send it my way!

Today’s script explores the good old fashioned horror premise of a main character who’s convinced she’s seeing a bunch of scary things, but is told by everyone else that she’s going crazy. Let’s find out if it’s any good.

30 year old Lizzie Fleischer is a first grade teacher whose life is on the up-and-up. She’s about to marry her boyfriend of four months, Stephen, who she’s madly in love with. Before she does, however, she has to put her past to rest. When Lizzie was a child, she used to go to her rich grandfather’s mansion, until one day when the family got into a horrible car accident and both her parents died. Lizzie wants to finally move past this trauma and seeing her grandfather again is the final step.

So up she drives into an endless forest until she finally comes upon the mansion. It’s a little more dilapidated than what she rememberers, but her grandfather still has a groundskeeper, the creepy Ben, who’s doing his best to keep things presentable. After she takes a look around and spots a few expensive pieces of hospital equipment (what are those for?) she finally meets her grandfather again, Dr. Rupert Fleischer.

We soon learn that the trauma was so intense after that crash, Lizzie barely rememberers anything about this place. So Rupert does his best to catch her up. It’s here she learns about the wing of the house that’s been “closed down” and not to be entered. Hmmm… I wonder what that’s about? Later, Liz wanders into the forest where she’s convinced she hears children playing. But this is both in the middle of nowhere and private property. There can’t be any kids around here.

That night, Liz wakes up to hear kids’ voices IN THE HOUSE. When she asks Ben and Rupert about this in the morning, they look at her like she’s nuts. But Liz’s childhood memories start coming back, and some of them include a hospital. A children’s hospital here on the premises. The deeper Liz digs, the more skittish her grandfather gets, until he informs her that, in his professional medical opinion, she may be psychotic. Not to worry, however. He’s a doctor and will treat her. Aww, what a nice guy. What ever could go wrong in this scenario? Read “You’re Not Real” to find out!

The challenge with “main character may be crazy” movies is that the writer has too much power to fudge the world we’re in in order to fit his puzzle pieces together. Literally any strange thing that happens that makes zero sense or doesn’t work for the plot, the writer can lean on the fact that the main character was imagining it. Or not imagining it. It’s such a convenient position to write from. Technically, nothing in your script needs to make sense.

The other big issue I see in these scripts is that the authors have no clue what real psychosis is. The extent of their medical knowledge rests on a few quick wikipedia searches and a friend of theirs who used to be a pharmacist named Todd. True psychosis, or anything that has do with mental health, is a complicated subject matter. And most writers just don’t want to do the research to figure out how their character’s condition actually works.

The combination of these two pitfalls is what often dooms these scripts. Which is why I’m happy to say that Russell manages them well. He doesn’t knock it out of the park. But there’s a sophistication to both the characters and the plot that, over time, gives you confidence that he has a plan here. And that’s all I want when I read one of these “crazy person” mysteries. I want to feel like the writer has a plan on where he’s taking me and it’s going to pay off in a satisfying way.

The area where Russell’s script shines the brightest is in its detail. He does a very good job of describing the area and the house and the things Liz is seeing. Normally, it takes the screenplay’s beefier cousin, the novel, to pull this off. But Russell manages it do it in script form, despite the craft’s minimalistic requirements.

In the end, the only thing that needs to work when writing a mystery is, does the reader want to find out what happened? Your mystery has to be compelling enough to pass that test. And the thought of this man taking advantage of children, doing experiments on them, possibly even doing experiments on Liz, made me want to find out what was really going on. While I wouldn’t say the final explanation was great. It was interesting enough that I felt satisfied. This spooky little script was definitely worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Not every car driving deep into the woods needs to include almost hitting a deer (an early scene that happens to Liz). If you have an instinct to write something – a beat, a scene, a moment, a surprise – the most common reason for that is that you’ve seen it before. So if you’ve seen it before, do you really want to use it? If you like the idea, find a twist on it. At least that way, you’re bringing something new to the table. A very basic example of this is, how do you make two superheroes fighting interesting if we’ve seen a million superheroes fight each other already? Well, what if a superhero had to fight himself? Which is what Captain America has to do in Endgame. It’s hard to come up with these ideas because your brain always wants to do the least amount of work. You have to push yourself.

What I learned special DVD extras: Consider the fact that this is the second horror script I’ve read IN A ROW that had a major plot point where parents died in a car crash. That should tell you, when you come up with that idea, it’s probably because you’ve seen it before. Honestly, sometimes I think the only thing that separates the good writers from the bad ones is effort. Screenwriting really is a medium where the more you put into it, the more you get out of it.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A young woman gets a job at an investment firm where she’s the only African-American at the company.

About: This script made last year’s Black List, finishing with 7 votes. The writer, Meredith Dawson, wrote on Mindy Kaling’s Hulu adaptation of Four Weddings and a Funeral. She also wrote one episode of The Mindy Project 2 years earlier.

Writer: Meredith Dawson

Details: 107 pages

What I was hoping for when I opened this script was something akin to a workplace “Get Out.” Not only would that be a great pitch, but it’d probably make a good movie. If a friend told me, “You have to see this movie. It’s like Get Out, the New Girl at Work version,” I’d throw that in the Netflix queue right away.

Unfortunately, that’s not what we get. And I’m trying not to hold that against the script. One of the first lessons they teach you in review school is to review the movie you saw, not the movie you wish they’d made. I’m not sure that applies as much on a screenwriting site because sometimes the best way to explain something is to show how you could’ve done it better. And there’s a lot here I think they could’ve done better. Let’s take a look.

Naomi is a 27 year old African-American recent graduate of Stanford Business School who watches way too much Frasier on Netflix. On the night of her graduation, she hooks up with a gorgeous bearded white guy named Ben (page 9). The two are going their separate ways in life, however, so after they sleep together, they don’t talk again.

Naomi then starts her job at Harvey, Larter, and Saw, a venture capitalist firm where she quickly finds out that she’s the only African-American there. No worries. Naomi is used to this dynamic. But what she isn’t used to is when GUESS WHO shows up to team with her on her first job? That’s right, Ben (page 26). It turns out he works here as well!

Despite her attempts to keep her private life separated from her career, Naomi can’t help but fall into a steamy relationship with the sexy Ben. But Naomi’s beta-male co-worker, Nick, who secretly loves her, warns Naomi that Ben is bad. “How?” She asks. Nick says he knows these things and just has a feeling.

Noami and Nick put together a proposal for a new company to finance but Naomi’s boss, Iyana, flippantly rejects it. Weeks later, during a big company party, Naomi is shocked to see that Ben has brought a date. But not just any date. His girlfriend of six years (page 62)! Needless to say, Ben and Naomi’s relationship sours quickly.

But it gets worse. Ben tells Iyana she should invest in the same company Nick and Naomi liked, and this time Iyana likes the idea. So much so that she puts Ben in charge. Naomi asks Iyana what’s up and she says Ben was just more convincing.

Later, Naomi goes to a business dinner meeting with a client they’re trying to sign, an older man, and he puts his hand on her leg (page 88). Noami tells Iyana about it but Iyana does nothing. Disgusted with the way she’s been treated, Naomi decides to let the press know just how little her company cares about keeping women safe.

You’re probably wondering why I included page numbers in today’s summary. I did so for a specific reason. These are the only plot points in the script. By plot points I mean major plot developments that send the story in a new direction. Page 9, page 26, page 62, and page 88.

Four plot points for the entire movie doesn’t provide enough dramatic entertainment for an audience to stay invested. These are movies. They’re not real life, where it takes time for big things to happen. In movies big things need to happen consistently. We go nearly 40 pages between Ben’s arrival at the company and the reveal of Ben being in a relationship. And I would even argue that that’s B-story stuff. It shouldn’t even be the main plot.

Another issue is that there isn’t enough conflict. Conflict is the screenwriter’s best friend. You should always be looking for it. Your hero should be encountering obstacles and problems and issues from every direction. That’s what makes watching characters interesting, is seeing how they deal with the things that are thrown at them.

The first 60 pages of “Spark” is basically Naomi loving life, a party on the page, a 1 hour drive down Easy Street. That’s unacceptable in a feature screenplay. It also makes the ending weird. Because for 60-80 pages, this is a light soap opera. Girl meets guy. She falls for him. Turns out he’s in a relationship. So to then make the ending incredibly serious with major sexual misconduct allegations felt like it came out of nowhere. Had there been more conflict at work and had the tone been darker throughout, it might’ve worked. But in its current iteration, the final act felt like a different movie.

How would you fix a script like this? For starters, you have to understand the 3-Act structure. Something big needs to happen at the end of the first act. Something that sets the story in motion. Today’s writer made Naomi starting work the end of the first act. That’s not enough. It’s just continuing the good vibes. A seasoned writer would’ve gotten Naomi into work within the first five pages. And they would’ve had the sexual misconduct happen at the end of the first act. The movie, then, would be about dealing with the ramifications of what happened, trying to get someone to do something about it while, at the same time, trying to maintain your professionalism, your relationships, and your job. I haven’t read the Roger Aisles script that’s coming out but I can guarantee you the first instance of sexual misconduct isn’t going to happen on page 88. What this essentially means is that Spark has an 88 page first act. And that’s just not understanding screenplay structure.

There were other problems as well. 10-line paragraphs (this is one of the easiest ways to spot a new writer), a lack of clarity in the genre (is this a drama, rom-com, a dramedy?). All the business-speak consisted of buzz words and buzz acronyms minus the necessary specificity to connect it to the story (“But HEAL is puttering out high dividends for a company as young as it is AND we’re on track for FDA approval within the next year.”).

With that said, the writing itself was strong. Unlike that awful script I reviewed in the newsletter where I could barely get through a sentence, the prose was never overbearing and the writing was insanely easy to read, to the point where my eyes were shooting across the page and I never got lost.

But this script is not ready for primetime. There are too many Screenwriting 101 mistakes here. I was hoping for more.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As a screenwriter, one of the things you have to be good at is getting a lot of story across quickly. Take the storyline of Naomi sleeping with Ben and then finding out he works with her. That took 26 pages here. In the Gray’s Anatomy pilot episode, they use the same storyline. And yet it took them less than 8 pages. And that was a TV show! Where they don’t even have to move fast. Whatever you think is the proper pacing for moving your plot along, it could probably move along faster.

THE NEWSLETTER SHOULD BE HITTING YOUR E-MAIL BOXES RIGHT ABOUT NOW!

Sorry guys. No post today. I was going to review Shadow of the Moon but the first few minutes were so bad, I put Netflix on a time out in the corner. I don’t even know how Netlflix production works. Nobody hears about these films until one day they just appear out of thin air. What Netflix doesn’t understand is that, if a movie falls in a forest and nobody’s around, it doesn’t get taken seriously. Their whole method for producing movies is bizarre and I struggle to understand it and NO Netflix, you may not get out of your time out early. Back in the corner!

Anyway, I don’t mean to toot my own horn, but this is probably the greatest Scriptshadow Newsletter EVER. I share with you the single worst idea for a show or movie I’ve ever seen. I tell you the number 1 thing that gets my knickers in a bunch when reading a script. And it isn’t a Scriptshadow newsletter if I don’t share my thoughts on the latest Star Wars news. I mathematically break down what number Rise of Skywalker has to hit at the box office to ensure Disney doesn’t blow Lucasfilm up and start over. I check out an overlooked movie and explore its connections with the golden age of the spec script. I dance. Although I didn’t include that part so you’ll have to imagine it. And I explain to you the industry reason why the script I review in the newsletter got purchased, even though it probably shouldn’t have.

It’s a smorgasbord of screenwriting awesomeness. But you can’t read it unless you’re signed up. If you’re not on the Scriptshadow Mailing List, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you e-mailing me saying that you keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

This has to be one of the more eclectic group of scripts that have been featured on Amateur Showdown. We got something from every corner. We’ve got jihadi fighters, a slave horror flick, a dad-daughter comedy team-up, and a heist flick with a – stop the presses – original premise. Should be a fun weekend. In the meantime, I’ll be working on the end of the month Scriptshadow Newsletter. I’ll give you a quick teaser. I just saw THE WORST MOVIE OR TV IDEA EVER. I’m talking in the history of ideas. And it got made. And it’s coming out. I can’t contain how frustrated I am that someone actually made this. But to find out what it is, you’ll have to wait for the newsletter. If you want to sign up for the newsletter, e-mail carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “NEWSLETTER” and I’ll make sure you get it.

Amateur Showdown is a single weekend tournament where the scripts have been vetted from a pile of hundreds to be featured here, for your entertainment. It’s up to you to read as much of each script as you can, then vote for your favorite in the comments section. Whoever receives the most votes by Sunday 11:59pm Pacific Time gets a review next Friday.

Got a great script that you believe can pummel four fellow amateur scripts? Send a PDF to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Good luck, everyone!

Title: THE BLACK PETREL

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Logline: A frustrated novelist goes to an old Southern hotel looking for inspiration and finds herself trapped in a nightmare with five strangers and a vengeful ex-slave.

Who am I: A writer trying to feed a hungry audience something delicious.

Why You Should Read: If GET OUT and A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET got pregnant listening to a Nina Simone song, this is the baby that would pop out.

Title: SINJAR

Genre: Action / War / Thriller

Logline: A foreign aid doctor enlists the help of a unique unit to rescue her fellow captives and escape through the Islamic State, pursued by a ruthless zealot and a horde of jihadi fighters.

Why Should You Read: “Sinjar” is an adrenaline-soaked feature depicting the realities of conflict in the Middle-East, in particular, the attempted genocide of the Yazidi during the summer of 2014. Imbued in this story are my own experiences of war, terrorists, and the land of Kurdistan…

Blacklist: “nonstop, action-driven thriller that can rival any other shoot-em-up war movie, but what makes it special is the depth of the story that it reveals beyond the set pieces. More than your average action flick, this script digs offers themes and commentary that dig at the heart of the conflict in the Middle East: the history, socioeconomic challenges, and cultural divides that have created that quagmire. It asks poignant questions about the consequences of military conflict, and follows those questions up with real answers from a real, specific point of view.”

Wescreenplay: Consider 8/10

Various: “The writer of this work has crafted a visceral, unrelenting narrative” “a kinetic blast of entertainment.” “the action in these pages is stellar.” “a fast-paced blistering thrill ride.”

Title: Good Blood

Genre: Action-Comedy

Premise: An inexperienced female agent must team up with her overprotective father to stop a bunch of armed yokels from overthrowing the government.

Why You Should Read: It’s a girl-with-a-gun action-comedy featuring a male-female buddy dynamic. In other words, three trends that Carson recommended for comedy scripts. The script has been through a number of drafts, so it should be tighter than my a&$#&le before my girlfriend pegs me.

Writer: Anonymous… for now (Just like Carson was).

Title: Money to Burn

Genre: Heist

Logline: A terminally-ill architect with a troubled past is recruited by a group of would-be thieves who plan to steal $70 million from a government facility that burns retired currency.

Why You Should Read: Money to Burn looks at the American dream turned sour through the prism of real people in real situations. Money means food on the table, pure and simple. The heroes in Money to Burn are what society would label criminals, but they are not Ocean’s 11 style super-cool, super-gifted criminals, they are everyman types who made wrong decisions along the way. Money to Burn focuses on their humanity rather than their criminality. — Money to Burn has a traditional denouement, a major set-piece heist which ends with a unique robbery, but the story is really about how a group of sick, dying men and women learn to live and love while collectively facing their imminent end. It’s a story about a unique support group where you have to be dying to gain entry.

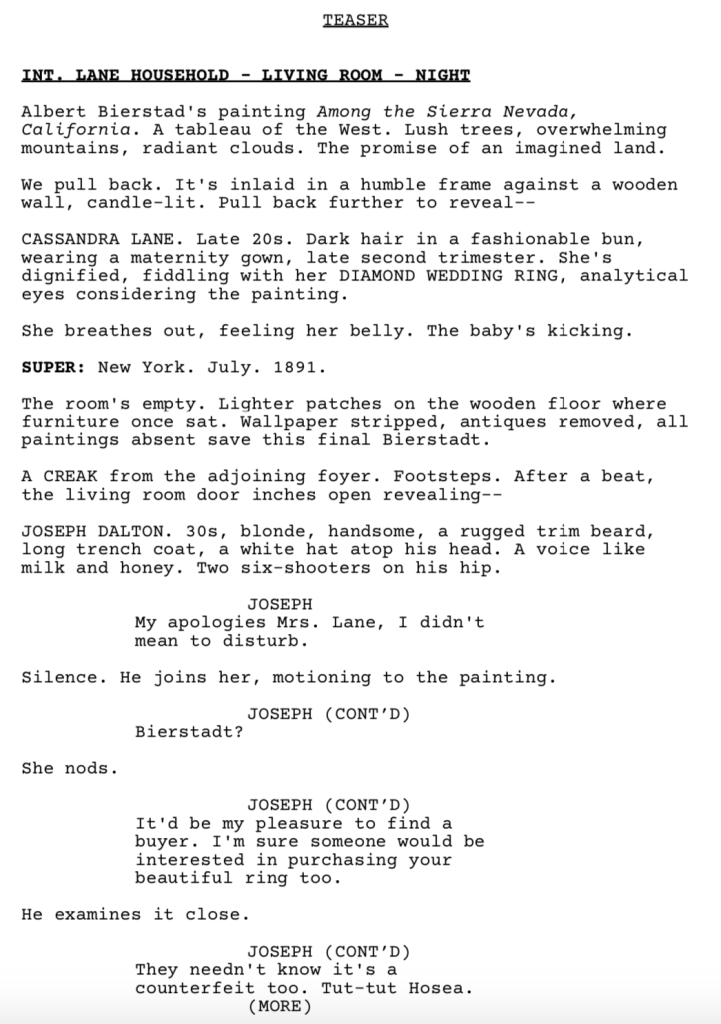

Title: Odyssey

Genre: Western/TV Pilot/Drama

Premise: A fierce pregnant widow makes a deal with a degenerate grave-robber to help her escort a herd of cattle across the Old West while the psychotic creditor that drove her husband to suicide and murdered her father stalks her across state-to-state, determined to make her pay up, or worse.

Why You Should Read: My bread-and-butter trademark is to take a tried and tested genre and write a new interpretation of old tropes. I think we all love westerns for the grizzled stares, the melodramatic music, and the collective fantasy of a lawless land. I do too. But I’m more interested in what the genre can do in the modern-day, not confined by what your Dad might like to watch on a sleepy Sunday afternoon. Odyssey is a pilot for a mini-series that honors what has already been done in the genre, but also takes it forward into new, exciting directions.