Genre: High School Comedy

Premise: When two nerdy seniors realize they’re the only girls in class without boyfriends, they try and use the same skills that made them straight A students to ace the ultimate test: find dates for the prom.

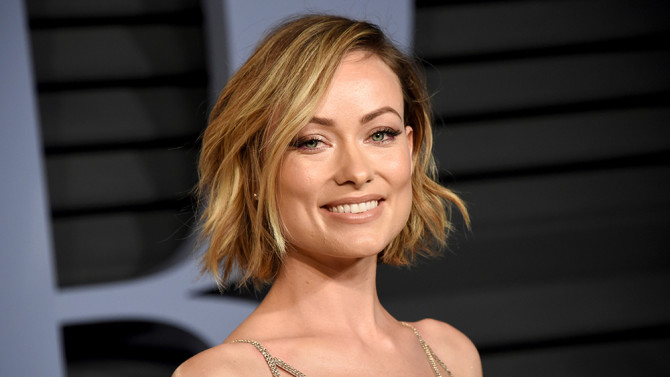

About: Booksmart is the directorial debut of Olivia Wilde. It just premiered at SXSW to good reviews. What’s interesting about this project is that the script was written all the way back in 2008 and chronicled the three months leading up to prom for its two heroines. However, the SXSW program summarizes the updated story this way – “A high school comedy about two best friends who decide to spend the evening before graduation cramming four years of partying into one wild night.” This tells us two things. One, that scripts evolve. The story you start with is almost never the story you finish with. And two, Wilde (or whichever producer helped develop this script) wisely incorporated some good old fashioned Scriptshadow advice – CONDENSE. YOUR. TIMEFRAME. The more condensed your timeframe, the faster your story will move.

Writers: Emily Halpern and Sarah Haskins

Details: 121 pages (11/24/08 draft)

Let me make something clear.

When I see a comedy screenplay that’s 120 pages long, I know immediately I’m dealing with a beginner. There is no reason whatsoever for a comedy spec to be 120 pages. Professional writers know this. So as soon as I see that horrifying number, I’m expecting problems. And it wasn’t long before I found them in Booksmart.

This script wanders through its first act like an old woman with Alzheimer’s. Your first act turn occurs when your characters begin the pursuit of their goal. The goal in this movie is to find prom dates. The characters don’t announce that until page 37!!! That would be 12 full pages after it should’ve been announced (page 25).

Some of you may say, “12 pages isn’t that long, Carson.” And you’d be wrong. A reader can get bored with a script within half a page. I don’t need to tell you guys this. You experienced it yourselves reading some of the 10-Page Finalists this weekend. Readers reading your scripts are no different than you reading those scripts. They’ll lose interest in a heartbeat if you’re not keeping things engaging. So if you’re plopping down an extra 12 pages before you even tell us what your script is about? Expect us to get bored.

And yet, this script got made. How is that possible? Read on to find out.

Molly and Amy are seniors at a high school in a small Michigan town. They’re also huge nerds. Sure, they both got into great universities. But they’ve never known the touch of an adolescent boy who’s just gone through puberty. And make no mistake, both Amy and Molly want to know what that touch feels like.

They try going to parties even though they don’t see the point of them (you don’t get graded so…?). And it’s during one of these parties that they realize every senior girl they know has a boyfriend. That night they have a eureka moment. What if they spent just as much time and energy on getting dates for prom as they do studying for school? It’s time to put those booksmarts to the test.

After this initial plan goes nowhere, the two recruit their old friend Julie, who’s somehow landed a hot college boyfriend and therefore knows what she’s talking about. Julie says the most important thing they need to do is be around guys more, specifically the guys they like. So she assigns Amy to join the softball team, since her crush plays baseball and both teams travel together. And Molly must join the high school play, since her crush is one of the actors.

The plan sputters from the start. Neither girl makes any headway. And on top of that, their friendship starts to fracture! They will need to pull it together if they want to go to prom with actual boys, a task that that’s looking increasingly outside of their particular set of smarty-pants skills.

Booksmart is a dangerous script to read if you’re an aspiring screenwriter because after finishing it your first thought will be, “That’s it? This script got recognition and mine didn’t??” Booksmart feels more like a writing team learning how to write a screenplay than it does a finished product. So here’s something to keep in mind. This script took 10 years to get made. It’s likely that someone liked the idea and decided to develop it with the writers. Through those rewrites, the script became more polished before it was finally ready to be placed in front of someone like Olivia Wilde’s eyes.

If there’s a lesson here, it’s that as long as there’s a kernel of a hook at the center of your screenplay, there’s a chance – even if the rest of the script is weak – that somebody will want to explore it. This hook of nerds applying their particular set of nerdy skills to get boyfriends is a fun one. I’m going through this myself. There’s a script I read last year that has a great hook but the writer is a total newbie. He’s not ready yet. So I have to decide do I want to work with him on the script and try to guide him towards a salable screenplay. I like the idea enough that I’m considering suffering through endless rewrites where I’m basically teaching the writer how to write. This kind of dilemma happens to producers every day in Hollywood.

As for the story I read today, it’s a classic example of writers feeling out a medium they don’t yet understand. For example, there are a lot of these quick goofy flashbacks. Like when Amy and Molly realize they’ll have to go to parties to get boyfriends. “Remember the last time we went to a party?” Flash back to Molly and Amy showing up to a party at 6:30pm. — I’m not saying this isn’t funny. But it’s the low hanging fruit of the comedy screenwriting world and I see it with beginner screenwriters a lot. I guess the best way to put it is – any writer could come up with this idea. To stand out as a screenwriter, you got to give us stuff we’re not used to seeing.

Another mistake beginners make is they think they have to set up a lot more than they actually do. I could tell the writers wanted to write about these smart girls who drop everything to learn how to get boys. And yet two nerds obsessed with academia would never just “drop everything.” So Halpern and Haskins write several early scenes to establish that Molly and Amy are “second semester seniors” who’ve already gotten into college and therefore don’t have any commitments. They literally write a scene where a teacher says, “You’re second semester seniors. You can go have fun now. It doesn’t matter.” There are some story points that the audience doesn’t need spelled out for them. If you choose to include these story points anyway, your script takes forever to get where it’s going.

The pacing problems continue into the second act, as we’re occasionally given updates on the prom countdown. Unfortunately, this works against the script. We’ll get a title card that says: 63 days before prom. Then we’ll spend 15 more pages watching the girls get ready and a new title card appears: 52 days before prom. STILL??? Countdowns work well when there’s, say, 5 days left. They don’t work well when there’s 50 days left, lol.

That’s not to say the script was all bad. It felt, at times, like the high school version of Broad City, which I love. There’s a lighthearted vibe to the proceedings. Both our characters are underdogs and likable. While the dialogue doesn’t pop off the page like, say, Juno, listening to Molly and Amy is a bit like listening to a couple of friends who are having a good time. But the simple truth is that this is the “before” thumbnail in a weight loss video. I’ll tell you what the “after” photo looks like when I see the movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “As Molly and Amy pass the cashier, we cut to the standard wide shot of a high school cafeteria.” It was action lines like this that screamed “newbie” throughout Booksmart. This line of description does two things wrong. One, it’s breaking the reader’s suspension of disbelief by mentioning a “shot.” Don’t mention shots in screenplays. And two, nothing should ever be “standard” in your script. When you write that, you’re basically saying, “Here’s a boring shot you’re bored of cause you’ve seen it in all those other boring movies that show similar boring shots.” How does it make your script look when you’re admitting that you’re giving the audience the exact same shot they’ve always seen? Come on. Sell the moment! Even if it’s a standard shot, commit to describing it.

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Premise: (from IMDB) Five former Special Forces operatives reunite to plan a heist in a sparsely populated multi-border zone of South America.

About: Frequent collaborators Mark Boal and Katheryn Bigelow were set to make this film back in 2010 with Tom Hanks and Johnny Depp. As happens all the time in Hollywood, development lagged long enough to see both Hanks and Depp leave, and soon even Bigelow dropped out so she could make Detroit (bet she stands behind that decision). The movie rose from the ashes when JC Chandor (Margin Call, A Most Violent Year) came on. He was joined by Depp again, Will Smith, Tom Hardy, and Channing Tatum. But the film wasn’t out of the clear yet. With just weeks before shooting, everything fell apart and the producers had to start all over again. That led us to the current cast, which includes basically plays himself Ben Affleck, constantly slips into a British accent Charlie Hunnam, and Chandor’s Violent Year star, Oscar Isaac.

Writer: J.C. Chandor & Mark Boal

Details: 125 minutes

Correct me if I’m wrong but I think this is the first time in history that the major movie release of the weekend came out on Netflix. What does that mean? I don’t know. I know Steven Spielberg has an opinion or two about it. But what’s unique about Triple Frontier is that it’s clearly an experience that works better on the big screen. This isn’t some goofball comedy. The helicopter sequence through the South American jungle alone is stunning enough that it would’ve shined at the Arclight. And yeah, I know, they put it out in theaters for a week. But it wasn’t a real release. It was in case the movie was nomination worthy.

As a lot of you know, I loved the Triple Frontier script. But I’ve been tepid about how it would translate, specifically because of Mark Boal. Boal gives you a specific kind of movie and doesn’t seem to know how to work outside of that. I remember watching Boal’s Zero Dark 30, being underwhelmed, and wondering why. On the surface, it should’ve worked. We’ve got a real life story about the hunt for the most notorious terrorist in American history. And yet it was boring. Why?

Then it hit me. The script only hit one beat: Serious. Every scene was about the serious nature of what they were doing and the serious problems they ran into and the serious characters who had serious opinions and serious discussions about those serious opinions. A movie should be a roller coaster. It should not be a train ride. We have to go up and down, sometimes even in a loop, to keep the story interesting. Boal doesn’t know how to do that and his screenplays suffer as a result. They’re never bad. But it’s impossible not to become a numb viewer when every scene is the same.

JC Chandor is a better screenwriter than Boal. But he operates in the same world. His stories tend to take themselves seriously. So I wondered if a collaboration between the two would do what you want collaborations to do – elevate the material. You want your co-writer to be strong where you’re weak, and vice versa. Not sure that was the case here. And yet the old draft I read was strong. Let’s see how the movie turned out.

Pope (Oscar Isaac) is an ex special forces soldier who’s doing bad guy clean-up work in South America. When Pope learns that one of the biggest drug dealers in the world has tens of millions of dollars stashed at his home in the jungle, he recruits his old special forces buddies, Redfly (Affleck), Ironhead (Charlie Hunnam), Ben (Garrett Hedlund) and Catfish (Pedro Pascal), to steal it. The “hook” here is that these guys have always abided by the law. This is the first time they’re going to break it.

The group flies to the Triple Frontier, the tri-border area along Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil, and start prepping for the heist. Redfly is the taskmaster. He makes it clear they’ve got a small window to get this done and if any red flags pop up, they bail. The group is shocked when they finally execute the heist and there’s 10 times as much money as they planned for. Now they have a new challenge – get all this money back to the US somehow. They’ve got a helicopter but it wasn’t ready for this kind of load. They’ll have to get creative and take some chances if they’re going to succeed. Of course, in the end, greed gets the best of them.

I liked Triple Frontier.

But it’s a frustrating movie in a lot of ways.

Somewhere along the 10 years of development, Boal and Chandor forgot to hit the beats that really matter, starting with the title itself.

In the script, it’s made clear why the Triple Frontier is such a badass place. They explain it’s the earth’s equivalent of Mos Eisley, one of the most crime-ridden dangerous places in the world. However, in the movie, you don’t even know what Triple Frontier is. You just know it’s the title. The reason this is frustrating is because the history behind the triple frontier sets up why this one guy has so much money stashed at his house. He’s the top dog in one of the most lawless places on earth.

This problem of forgetting to highlight the big moments when they happen continues throughout the screenplay. When the team gets to South America, we spend 25 minutes preparing for the heist. Then, out of nowhere, we’re in the house executing the heist. The moment came so stealthily, I assumed they were doing a test run. About midway through I realized this was the real thing. The heist is the most important moment in the movie! Why wouldn’t you make it clear it’s happening!

One of my favorite moments from the script was when they learn they’re not stealing 25 million dollars. They’re stealing 250 million dollars. Everyone’s excited but they also realize this changes everything. They weren’t prepared for this kind of load so now they have to rethink the plan. But in the movie, this moment occurs passively. They’re at the helicopter and Catfish and Pope have this conversation that amounts to, “Oh, by the way, we have 250 million dollars now so it’s going to be a little trickier.”

This was the irony that made the script so cool! In every one of these movies, the thing that goes wrong is that they end up with LESS money than they hoped. Triple Frontier flipped that and said, ‘No, we’re going to give you more. Lots more!’ But what seems like a good thing is actually what does them in, cause they didn’t plan to handle this much money but their greed tries to make it work anyway.

As for the changes in the script, I noticed a couple of things. The first is how the money is found. In the script, they go to the room where the money is supposed to be but it’s not there and they freak out. Then someone notices that the ceiling is leaking cause it’s raining outside. Which means they probably moved the money. The group keeps on looking and, indeed, it’s in another room. I liked the scene because you always want to throw curveballs at your heroes. It can never be easy for them. They show up, they think the money’s gone, but then they realize it’s somewhere else.

Boal and Chandor improve on this, however. Instead, the group shows up, the money isn’t there, they’re momentarily defeated, then someone realizes it’s in the walls. So they start breaking through the walls and ripping the money out. This achieves two things. First, it’s way more cinematic. The previous scene had them taking money off a pile of money. This version has them breaking walls to get the money. It just looks better. It also adds a component of urgency – do they have enough time to break down all the walls and get all the money? It turns out they don’t, which throws the operation off.

The other change they made is jumping into the heist sooner. In the script, the prep section was the longest section of the script. And, to be honest, not a lot was happening there. Prepping is tough in screenwriting because there’s something inherently repetitive about it. And I think Chandor realized that at some point and sped it up. I would even venture to guess that they shot the extra prepping and only realized in editing that they didn’t need it. Which probably has something to do with the neutered announcement of the heist itself.

I loved the helicopter stuff in the script and I love it here in the movie. The best you can ask for in screenwriting is a story that shines by showing and not telling. So if you’re writing a movie about greed, having a bunch of characters talking to each other about how much they love money and how they play the stock market and what car they just bought – that’s the worst possible exploration of greed. The best is in this movie. A helicopter is carrying a bunch of money through mountains that it’s not light enough to get through. So the characters literally have to decide how much money is worth their safety. We see their greed in that they can only push out so much money, even if it means risking their lives.

Another great example of this is Redfly (Ben Affleck). He’s the most practical of the group. He’s the one saying, “We’ve got this many minutes, we’ve got to hit this checkpoint by this time, that checkpoint by that time, if there’s any fluctuation, we ditch.” And then, when they find the money in the walls and they’re desperately trying to bash out as much as possible, it’s Redfly who’s the first one yelling out, “Don’t worry! I gave us a buffer!”

I can’t get past how much I love this idea. You’ve stolen all this money but to get from Point A to Point Z, you have to keep making decisions about how much you can leave behind. It’s the ultimate exploration of greed. And while I would’ve liked for Chandor to treat this more like a Hollywood movie with big beats as opposed to a “true story” like Zero Dark 30, I was still entertained the whole way through.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: HIT. YOUR. MAJOR. BEATS. HARD. Hitting your beats means when a major moment comes up in your story, you give it its proper due. For example, if a character has a baby, there’s an excitement that should permeate everyone associated with that character. The new mother doesn’t text her mom, “Had the kid. Still on for dinner, Sunday?” You must be true to the level of intensity that moment would provide. Triple Frontier doesn’t hit its big beats hard enough, from the triple frontier to the heist to the amount of extra money they stole. Those moments needed extra attention.

This was a fun experiment. It took me back to the days when I read 8 scripts a day. When you’re looking at that much material within that short of an amount of time, it’s easier to identify what doesn’t work. And the biggest thing I discovered by reading so much material back to back is how generic most screenplays are. For example, I read 30+ opening scenes that dealt with cops arriving on a murder scene. 20+ opening scenes that dealt with a bank robbery. 15+ opening scene with characters starting their day. But it wasn’t just the generic nature of the setup. It was the generic nature of the execution. A bank robbery can be a compelling scene. But not if you follow the obvious beats (Get down on the floor. Give me your money. Run out and drive away). If anything, this exercise taught me that writers aren’t aware of just how much content they’re competing with and, therefore, how important it is to differentiate your work.

The next big issue I ran into was that a ton of these scripts started slow. Let me reiterate what this challenge was about. It was about hooking me from the VERY FIRST WORD and never letting go. I don’t know why anyone would think that a slow pan across a desert horizon was a good idea. Or the 40+ script openings that focused on how light was hitting something. Or plopping me down in a room with two characters chatting away. No doubt a sizable portion of these entries were writers sending their latest script in regardless of the exercise. But for those who understood the exercise and still started slow? Or even medium? Shame on you. You knew the rules. Hook me immediately. Not hook me on page 2 and a half.

Every once in awhile I felt bad because I wanted to give writers a fair shot. So I would read past the point where I got bored. But in every one of those cases, I was proven right. The script didn’t get better. It almost always got worse. And it’s frustrating because I feel like this is my fault. We talked about this for an entire month, with me going into detail about what works and what doesn’t and, still, writers are making basic mistakes. There were so many times where I would read the first half page, stop, stare at my computer, and wonder why anyone would think this would hook a reader.

To give you some stats. 80% of the scripts, I didn’t get past the first half-page. I’d say, of the 20% where I kept reading, 70% of those I didn’t get past the second page. The most common problems were…

1) The writer couldn’t construct a sentence.

2) The writing or the scenario was confusing.

3) The writer was more concerned with setting up characters than entertaining the reader.

4) The writer was more concerned with setting up their world (exposition) than entertaining the reader.

5) There was nothing original or unique about the writing or the situation.

6) The scene was straight up boring. Nothing was happening.

That last one bothered me the most because you’d think “Don’t be boring” would be obvious. And yet time after time we’d get these scenes that didn’t contain a single entertaining element within them. No drama, no conflict, no mystery, no comedy, no dramatic irony, no dialogue that popped off the page. I thought about this a lot and wondered why were writers violating something that was so obvious to me. I think the problem boils down to too many writers assuming you “owe them.” You owe them your focus. And when you’re writing with that mindset, you don’t care about keeping the reader’s attention. I can tell you right now, that’s a deadly mindset to have. If you want the reader to like your script, you HAVE TO GRAB THEM. And the only way to do that is to assume they’ll get bored unless you’re giving them your best.

If you could construct a sentence, if you could convey action clearly, if you started with a scene that could conceivably grab the reader, you made it past page 1. But now it’s a matter of, “Are you giving me anything new?” Anything new at all. It could be a reversal (that Silence of the Lambs example I used in a previous post where we’re led to believe the person being restrained is the victim, when in actuality, they turn out to be the bad guy). It could be a strong sense of detail that pulls me into the world. It could be pure talent, like Diablo Cody’s Juno dialogue. ANYTHING. If you did that, you got past page 2. But from here, you had to prove that you could construct a compelling scenario. For example, a writer might’ve opened on a shocking murder scene. Okay, you have my interest. But if the scene doesn’t build and contain conflict and move towards a satisfying conclusion, then I immediately lost interest.

If you could set up a compelling scenario, you got me to read the whole thing. And there were about 15 entries that got me to read all 10 pages. Four of those didn’t leave me with a good enough taste in my mouth to celebrate them here. The remaining eleven were all good. So here’s what I thought we’d do. I’m going to post the eleven winners here today and we’re going to do an impromptu 10 Page Amateur Offerings (which will last through the weekend). You guys will read the eleven entries and vote on your favorite. The winner will get a review next Friday. If the writer has a full script, I’ll review that. If they only have the ten pages, I’ll do an in-depth review on the pages, focusing on things we don’t get to normally explore when covering an entire screenplay. The winner will also get a feature consultation package from me! So really think about who you’re giving your vote to.

And I want to say one more thing to those of you who don’t find your pages here. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad writer. It doesn’t mean you failed. But you do need to redefine what grabbing a reader means. Because I know a lot of you are talented. And in almost every case with you talented writers, you wrote something better than average. But you didn’t write something that grabbed me. You didn’t write like your life depended on it, I guess you could say. If there’s anything I’ve learned from this, it’s that busy people whose lives revolve around reading and hearing ideas all day don’t have any patience. And you have to write with that in mind. Like I said when all of this started, write 10 pages that are impossible to put down.

Okay, here are our 11 finalists! Good luck to everyone! Oh, and these are my titles for the scripts, not the writers.

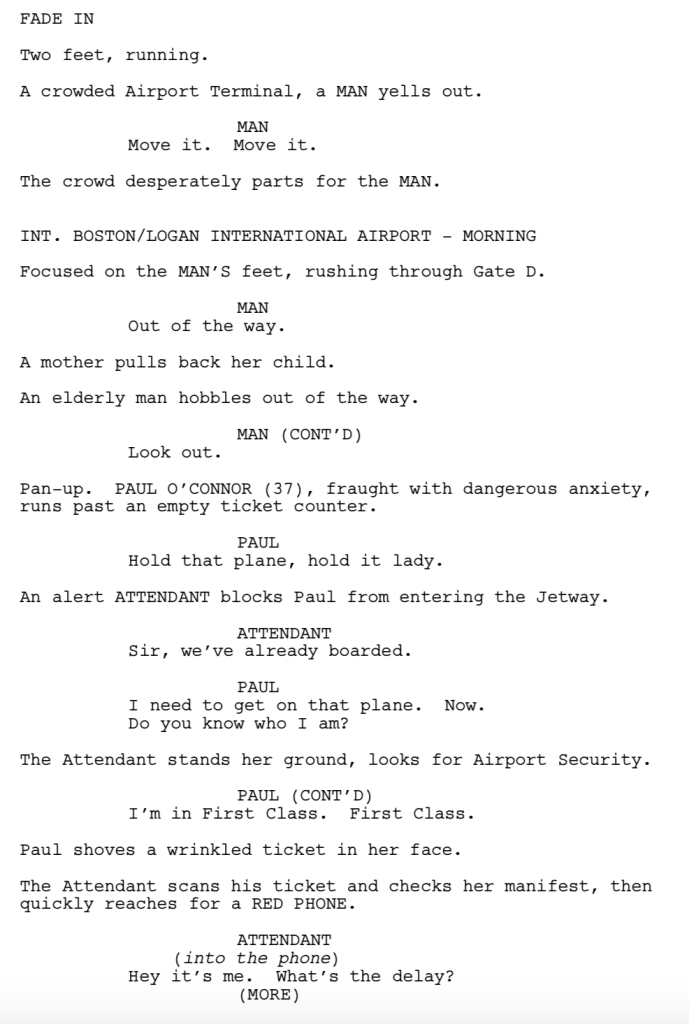

Entry 1: Late For A Flight

Reaction: Biggest “Oh s&*%” moment.

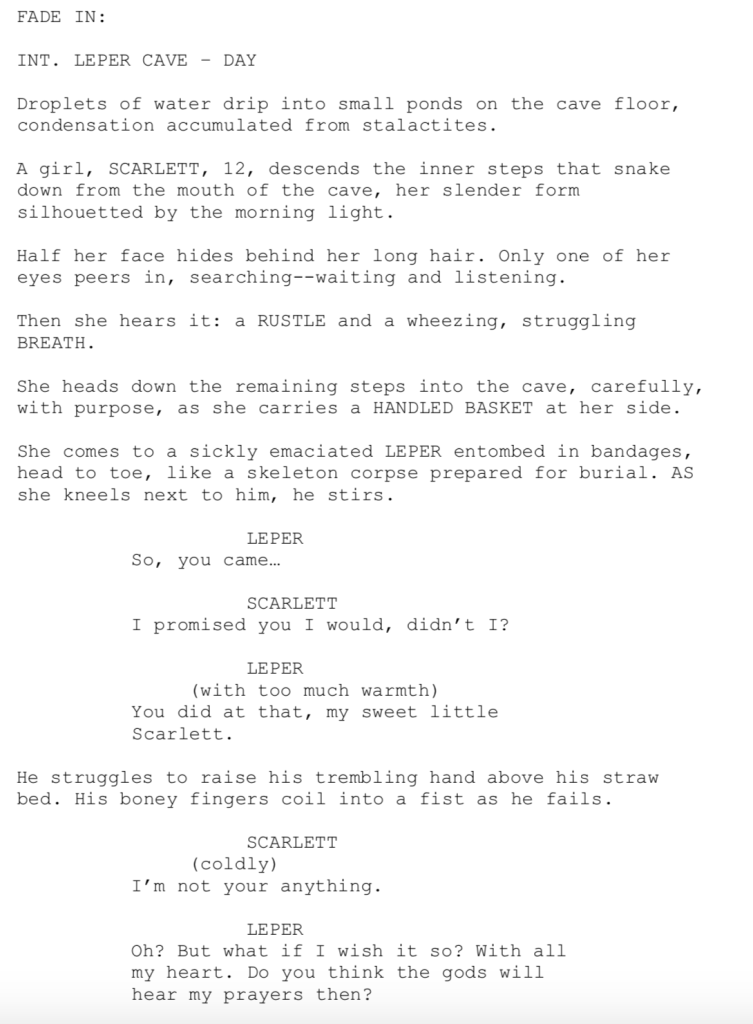

Entry 2: The Leper Cave

Reaction: Creepiest entry?

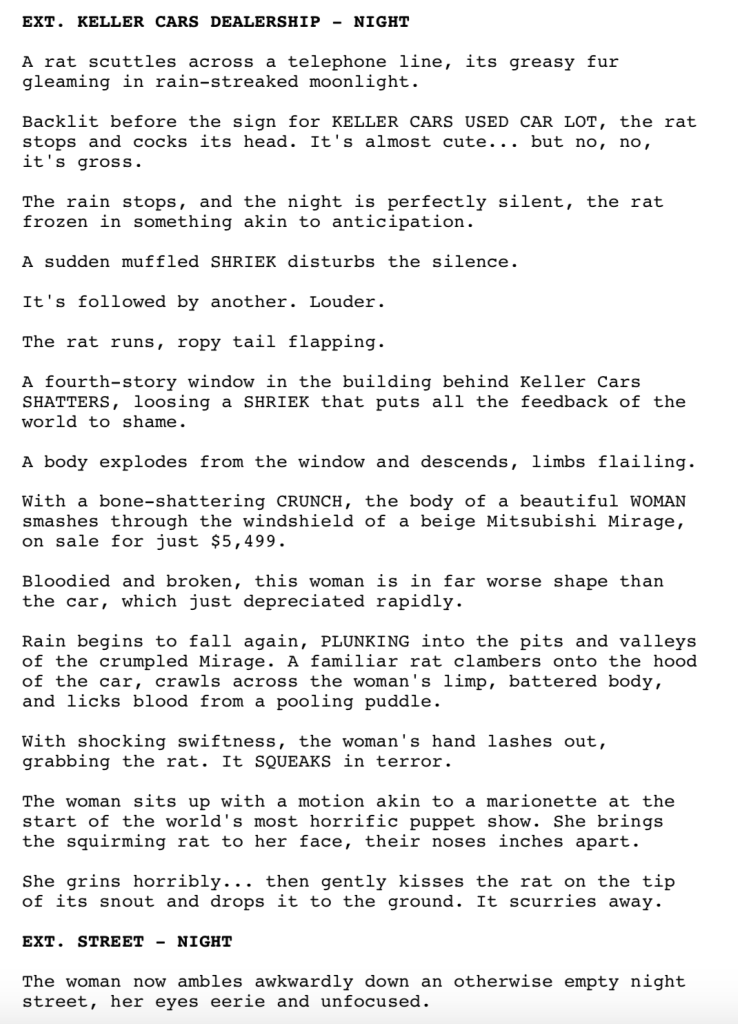

Entry 3: The Woman Who Disturbed the Rat

Reaction: Most talented writer in the bunch?

Entry 4: Cop Stop

Reaction: First entry that I read all ten pages of!

Entry 5: Waking Up in a Pool

Reaction: Top amnesia entry.

Entry 6: Confused Soldiers

Reaction: You knew time travel had to make it into a Carson contest somehow!

Entry 7: The Art of Pick-Pocketing

Reaction: Script I was most surprised I liked.

Entry 8: Pterodactyl Bliss

Reaction: Writer best suited for the current Godzilla franchise.

Entry 9: Roman Plagues

Reaction: Script that best took me back to a different time and place.

Entry 10: Don’t Take the Phone

Reaction: Fastest pages in the whole challenge.

Entry 11: Cocaine Problems

Reaction: Darkest entry of the bunch.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: A young woman turns 1970s Pittsburgh on its head, opening a string of successful massage parlors and parlaying the profits into a number of business ventures that made her the queen of the city.

About: Today’s script is the most controversial script on the 2018 Black List. The project became an instant Oscar contender when Scarlett Johansson signed on to play the lead. But immediately after that happened, the trans community attacked her online, claiming a straight woman shouldn’t be able to play a trans character. Challenging the very definition of acting, their argument was that only a trans person should play a trans role. The tactic worked, scaring Johansson off the project. It’s unclear if they deemed this a win, since, in chasing Johansson away, they killed a project that would’ve brought a lot of positive attention to the transgender community.

Writer: Gary Spinelli

Details: 120 pages

I can see why Scarlett Johansson wanted a Rub and Tug. This is a dream role for an actress. You basically get to play the lead in the first ever “Scorsese movie” centered around a woman. You get to play a lesbian, then later a trans person. You get to play someone consumed with money and power. You get to play the Connor McGregor of 1970s Pittsburgh, an outrageous personality with outrageous tastes. Johansson could’ve sent her stunt double to shoot this movie and she would’ve still won a Best Actress statue.

On the lame side, we’ve got yet another biopic. But, I’ll give Rub and Tug this. It’s at least someone we’ve never heard of before. I feel writers mail it in when they’re writing biopics about famous people, thinking the fame will do the work for them. But when you’re writing about someone we didn’t know existed, you’re basically writing a spec, which means you gotta work harder to earn our interest. And I was interested in Rub and Tug. At least for awhile…

It’s 1979 in Pittsburgh, a town full of blue collar workers all looking for a little release. That’s where 20-something Jean Marie Gill comes in. Jean gets this idea that she can monopolize the rub and tug business. She’s already familiar with the industry, as she’s been giving handjobs for cash since she became legal, and probably before that. And since Pittsburgh’s starving for new businesses, Jean soon has a handful of massage parlors up and running.

But not everyone likes the parlors, including Sebastian LaRocca, the current Godfather of Pittsburgh. Realizing LaRocca’s going to be a problem, Jean grabs her first officers and shoots him and his lieutenants dead. Now Jean’s the effing king of Pittsburgh. Not long after, Jean falls in love with Cynthia, who she meets because her husband frequents one of her parlors.

Around this time, Patti, the first female agent to work for the Pittsburgh D.A., comes sniffing around. She can’t bump into a crime that doesn’t somehow lead back to Jean. Needing to make a name for herself, she’s determined to take down Jean’s empire. Jean doesn’t take the threat seriously, expanding her business into steroids. In fact, she starts taking a few steroids herself in the hopes of become more manly. Eventually, however, Jean’s Jordan Bellforte like desire for decadence does her in, as Patti gets her on the Al Capone charge – tax evasion. And just like that, it’s all over for Jean.

Man, for a project so controversial, this script was as by-the-numbers as they get. The beats are way too similar to what we’ve seen before, almost like they were constructed after a marathon charting of every Scorsese movie ever. Start as a nobody. Rise up in the crime game. Take down your competitors. Lose yourself in excess. Fall in love with someone. The feds come after you. Montage montage montage. You lose in the end. Crime doesn’t pay.

The script is lucky that the main character is so strong because if she wasn’t, this would’ve been the most generic movie ever. Even then, I was expecting a lot more from Jean. Especially in regards to her transitioning. Her being trans is what sparked the whole controversy in the first place but there’s very little in here about converting or being trans. Maybe that’s my fault. The media made a big deal about it because anything trans was such a polarizing headline. But in reality none of them read the freaking script. Had they, they might’ve learned the movie was more about Jean the person than Jean the transgender person.

None of that matters, though, because the script is sooooo achingly generic. It’s cool that someone made the first big-budget female vs. female crime film ever. But does it matter if you can predict the beats 20 pages ahead of time? Patti is a virtual waste as the second lead, which should’ve been rectified. If you’re playing opposite the female version of Connor McGregor, you need to be strong, memorable, and have an equal number of demons that make you a worthy adversary. Instead we get an overworked mother who “wants to make a splash.”

Then there’s the ending. Jean gets arrested, goes to prison, and we cut to 12 years later where she heads to downtown Pittsburgh to see what happened to her city. She’s bummed out because there’s nothing left of her empire. But then she sees a few trans and gay people walking by so maybe she did have an impact? The end? What??? If there’s a definition for not knowing how to end your script, this would be it.

The script isn’t a total loss. It works best when we see Jean rising up the ranks. These are always my favorite sequences in Scorsese movies. Who doesn’t love watching the underdog become the top dog? But even that sequence is ripping off other movies (the LaRocca murder scene was clearly inspired by The Godfather). I don’t know. I’ve been reading so many pages due to the First Ten Pages Challenge that my mind is desensitized to the point of stasis. But this script needs an originality rewrite. Are there writers for that? “Can you make everything in this script more original?”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re writing a movie that’s similar to other well-known movies, I’d recommend not going back and watching those movies. Yes, they help you understand what works. But at what cost? Scenes and characters from the film will creep into your script. This is known as unconscious plagiarism and it happens to all writers. I know this because I’m constantly giving this note to writers in my consults. “You know this scene is the exact same scene from Movie X, right?” They never know.

Don’t shoot me! I’ve got 75 entries left in the First 10 Pages Challenge. I will for sure, 100%, absolutely, no more excuses, be done Wednesday night and have a post for you Thursday. In the meantime, enjoy this zany time-loop comedy.

Genre: Sci-fi Comedy

Premise: During a wedding, the bride’s older sister notices that one of the guests is acting bizarre. In an attempt to find out more about him, she inadvertently joins him in an endless time loop of her sis’s wedding day.

About: It was announced TODAY that this movie was being greenlit. It comes from Lodge 49 writer, Andy Siara, and will star Andy Samburg and JK Simmons. The film is being made by three first-timers – Siara, director Max Barbakow, and newly created production company, Limelight.

Writer: Andy Siara

Details: 115 pages

Today we’re reviewing one of the hottest trends in Hollywood at the moment – the time-loop sub-genre. Why is this sub-genre so hot? Cause it’s high concept on a stick. It’s the simplest (and cheapest!) version of a marketable idea out there. All you need for a time loop movie is two actors and a camera. We saw that with Meet Cute.

I just never considered that it would become its own genre. How many different ways can you explore the loop experience? Well today’s script takes things in a slightly new direction, focusing on the depressing side of being stuck in a time loop. But will it be enough to counteract the ubiquity of the idea? I’m curious to find out. Aren’t you?

Sarah is the 32 year old unmarried older sister of Tala, who’s getting married on this fine weekend in Palm Springs. Sarah is over the wedding before it starts, rolling her eyes and giving a mumbling commentary of the stupidity on display as bridemaids who start their speeches with “hashtag lifegoals” vomit out never-ending monologues about true love.

As this nauseating ritual continues, Sarah notices one guy, Nyles, who isn’t like the other guests. Not only does he lack a filter, but he doesn’t seem to care. About anything. It’s catnip to Sarah, who oogles and eventually snoogles him to the outer edges of the party. While they chat, though, Nyles is hit with an arrow. Yes, as in the kind that comes out of a bow. Nyles leaps up and runs as some rando chases him into a cave, continuing to shoot arrows at him. A concerned Sarah follows him in there, where she sees a giant light and then – CUT TO – the start of the day.

Nyles informs Sarah that by following him into the cave, she has entered into a never-ending time loop. No matter what they do, they can’t get out. Sarah is pissed, then curious, then pissed again, then gives into it. Soon she’s robbing stores and killing cops, fully embracing the rules of this strange universe she’s found herself stuck in.

Along the way, each of them drop a major game-changer on the other, which results in the “boy loses girl” portion of the screenplay. Which sucks because it’s not like they can move to a different country and never see each other again. They always wake up at this wedding. Eventually, Sarah is determined to stop the time loop. But that will mean years of studying. Which isn’t difficult when you have a movie montage on your side. Indeed, after many years of studying time, space, and physics, Sarah thinks she knows how to escape this nightmare. There’s only one problem. Nyles doesn’t want to leave.

Did NOT like this one initially. Mainly because of Nyles, who isn’t likable. He sits around all day and either complains, mopes, or throws up his hands and says “what’s the point?” This is something I don’t understand about writers. One of the easiest ways to determine whether a reader is going to like your hero or not, is to ask if people would like him in the real world. Do I like people who complain, mope, and don’t give a crap about anything? No, I don’t. So why would I like that person in a movie? It’s such a simple test. Why don’t more writers use it!?

Sarah’s not much better. She’s a downer. She’s depressed. She’s over it all. Which at least explains why the two are attracted to each other. But getting through their early scenes was a chore. Mopey comment followed by pissy observation followed by negative response followed by downer thought.

HOWEVER. As the script continues on, the downer conversations morph into something more thoughtful, with the two forced to evaluate what’s most important to them, seeing as they’re stuck here forever. I’m not a fan of “meaning of life” dialogue. It’s a one way trip into On-The-Nose City. But if it’s organic to the situation, it can work. And meaning of life chats are pretty darn organic when you’re stuck in a time loop.

I also liked how the script embraced absurdity. People attack each other with arrows. Every night at sunset, you can see dinosaurs in the distance, a side effect of being stuck in this universal glitch.

Not to mention, the script dropped a couple of fun whoppers in there that recharged the story. This is something I’ve definitely learned about time-loop scripts. Due to their repetitive nature, you need a plan for changing things up every once in awhile (spoilers). Nyles’ revelation to Sarah that he’s already slept with her thousands of times turned up the heat. And Sarah’s reveal that she was banging her sister’s fiance the day before their wedding was the real shocker. It was enough to keep me engaged, at least.

The problem this script faces is that neither of its leads are likable. And the script contains an overall depressing tone. Writers have to consider the mood they want their audience to leave with. Because everything they write – from the characters to the plot choices to the conversations to their writer’s voice – affects that. And sometimes you can write a good story but the reader leaves the script feeling down. And if they’re leaving the script down, they’re probably not recommending it to others. That’s how I felt here. “That was pretty good.” But the downbeat nature of it all left me with me a bitter taste in my mouth.

Of course, the opposing argument is that by being a downer, it’s capturing more of the “reality” of life. I’m not sure I buy that. But those who bathe in the darker shadows of life will. Palm Springs had just enough of a unique take on this setup that I’d recommend it. But it doesn’t hold a candle to Meet Cute, the current king of the unproduced time loop projects.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There seem to be two types of time loop setups. The first has your characters stuck in the time loop (Palm Springs, Russian Doll). The second has your characters initiating the time loop (Meet Cute). I like scenarios where characters dictate the plot. Movies like ACTIVE CHARACTERS and if your hero is purposefully resetting the loop, they are actively driving the movie. It can, of course, work either way. But you should always give first look to the ACTIVE scenario. Movies tend to work best when the main character is driving the plot (as opposed to the plot driving them).