Genre: True Story/Drama

Premise: This is the true story of Mathew Martoma, a hedge fund trader who many consider a Wall Street sacrificial lamb for the 2008 stock market collapse.

About: This is a highly ranked 2016 Black List script. It received 21 votes, placing it in that year’s top 10. The writer, Matt Fruchtman, doesn’t have any previous credits on the books, making this his breakthrough screenplay.

Writer: Matt Fruchtman

Details: 128 pages

I preach relentlessly about the importance of starting your script strong. So it kills me when a screenplay violates this simplest of simple rules.

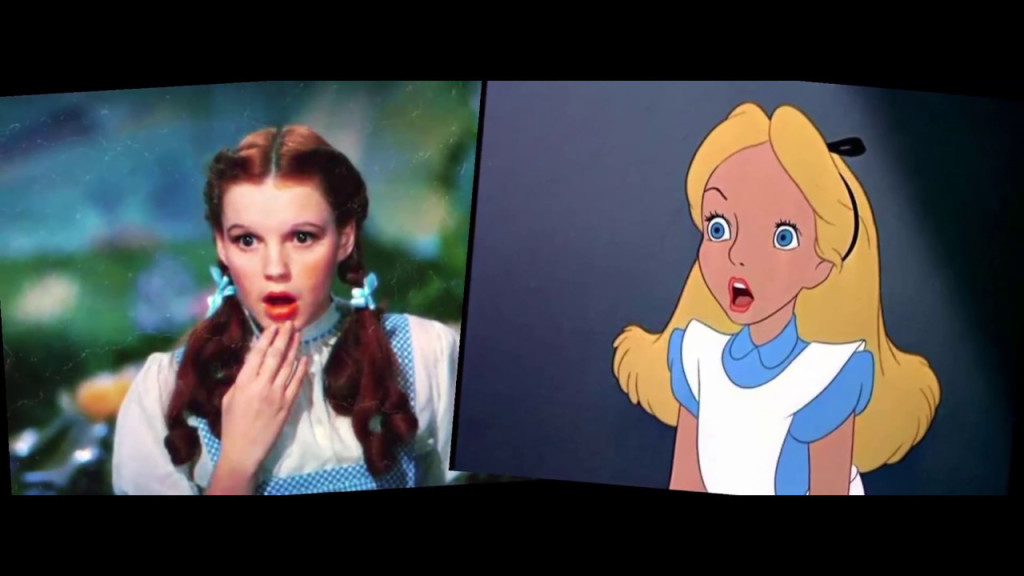

Although I didn’t get into it, I knew yesterday’s script was in trouble the second I read the first scene – an exposition dump. You never. EVER. in any circumstance. open your script with an exposition dump. With Dorothy and Alice, the first scene was all about a moon stone and the rules of the different worlds and what had happened to Oz and what our hero had to do now. I see a mistake like that and I know there will be more mistakes to come. And there were. The script devolved into a paycheck for a Santa Monica special effects company.

But in the case of Dark Money, a script I ended up liking, I didn’t connect with the opening scene either. Or the scene after it. Or the scene after that. It took me a good 50 pages before I was pulled into the story. And I can tell you the exact moment where it happened. But first, let’s summarize the story.

It’s 2006. 32 year old Mathew Martoma, a handsome Indian-American, is wrapping up the biggest job interview of his life. He’s informed by Steve Cohen, the head honcho at SAC Capital, a billion dollar hedge fund, that he doesn’t have what it takes. But after Mathew leaves, the private investigator Steve hired to look into Mathew informs Steve that he doctored some of his grades to get into college. That convinces Steve that Mathew will do whatever it takes to win, so he calls him up and tells him he starts tomorrow.

Unfortunately, working with Steve is like having someone bang you over the head with a space heater 50 times a day. All Steve does is tell Mathew that he’s dumb and won’t make it here. If that’s not bad enough, Mathew learns that SAC employees making a 20% return on their trades (a full 12% above the market) are getting fired. The pressure to bring record-breaking returns to this company is enormous.

So Mathew is more than thrilled when his doctor wife tells him about a miracle Alzheimer’s drug that’s going into trials. Mathew befriends the elderly doctor whose paper led to the drug, Sid Gilman, and, as a result, gets regular updates on how the trials are going. When it looks like the medication is going to be a hit, he gets his boss, Steve, to go all in on it. If this pays off, he’ll make Steve more money than any other trader has made him.

But as the release of the drug nears, Sid informs Mathew that the latest set of trials were ugly. At the last second, Mathew informs Steve of this news, and Steve executes a slimy trader move whereby he “shorts” his stocks via “dark pooling.” This allows SAC to not only abandon the stock without anyone else noticing. But also, if the stock bombs, SAC will make an insane amount of money.

“Shorting,” is a morally reprehensible thing to do because you’re basically profiting off of everybody else’s misfortune. It turns out that this particular short occurs during the giant financial meltdown of 2008. So immediately afterwards, with the world’s biggest newspapers demanding culpability, the FBI needs to take people down. Enter BJ, a faux-hawked Korean FBI agent who has his sights set on Steve. However, Robert Mueller (yes, that Robert Mueller) tells him that you can’t put billionaires in prison. It’s impossible. Well then who the hell can we take down, BJ asks. It turns out Mathew, who committed insider trading, is the easiest target.

Mathew ends up getting 9 years in prison while Steve gets… well, I’ll let the closing title card tell you: “After paying the fine, Steve Cohen immediately purchased a $60 M Hamptons home and an $155 M Picasso. He was never charged criminally.” And this, my friends, is America!

So let’s get back to that opening scene. Why didn’t I like it? It wasn’t a bad scene, per se. It was a job interview. The stakes and tension are inherently high in job interview scenes so I was game. But the dialogue straddled the thin line between cool and try-hard, to the point where it became distracting. Being able to write showy dialogue authentically (Fruchtman: “They speak in a rapid-fire testosteronese, not really listening but preparing to counter-punch each other’s remarks.”) is such a fragile practice. Try too hard and we, the reader, begin focusing less on the characters and more on the writer writing them (“Say I put you in a time machine. Bit of an alternate universe. September 11th 2001. You come to work here. First plane hits the tower. 9:46 AM this time. What trades do you make as soon Allah Akhbar Airlines smashes into the North Pole of American finance?”). It’s a game where unless you’re a true master, it can backfire badly.

When I read a script, I want to disappear into the story. I don’t want to be reminded that someone’s writing it every couple pages. So I waded through the following scenes carrying a grudge. I kept waiting for the storyteller to disappear. Meanwhile, the script was feeling more and more like a poor man’s “The Big Short.” But then something happened. And here’s the big screenwriting lesson of the day. Fruchtman introduced a PROBLEM. Mathew had spent 30 pages staking his reputation and livelihood on the Alzheimer’s stock. So when he’s told that the medication is garbage and the stock is worthless, his entire world is flipped upside-down.

It isn’t just that a problem has arisen. It’s that it’s a BIG PROBLEM. One big problem can make a movie. And, indeed, the script gets 1000% better the second this problem arrives. Now, every scene requires a choice (for example, what does he tell his boss?), as opposed to focusing on the daily activities of too-cool-for-school stock brokers. And once Mathew makes the choice to short the stock and deceive the market, we know it’s only going to get worse from thre. Once you have a character in freefall, it’s hard to screw that up. The audience is going to want to see if they can get out of it.

Still, I thought Fruchtman could’ve gotten so much more out of this story. The script kind of makes Mathew the bad guy. And make no mistake, he did break the law. But it should’ve been clearer that he was the fall guy. The question everyone wanted answered in 2008 was, why are these billionaires allowed to gamble our money away then get bailed out? More focus needed to be placed on taking Steve down and explaining the intricate web of reasons why he, and others like him, couldn’t be arrested. These movies are about sending audiences out in a rage so that they demand change. But the ending to Dark Money was just sad.

We’ll see if Dark Money gets made. Working against it is the fact that the best movie ever about this subject matter already came out (The Big Short). Studios may wonder why even bother. Then again, if Hollywood’s Diversity Movement needs another feather in its cap, two of the three main characters in Dark Money are Indian and Korean. And ALL of the characters in this story are interesting. It’d be an actor’s paradise. We’ll see what happens. In the meantime, if you want to read something good. Dark Money will do.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “freefall” plot device. Put your character in freefall and the script will write itself. One of the best movies of all time, Fargo, is great precisely because it follows a character, Jerry Lundergarden, in freefall.

As we anxiously await the end of the year screenwriting lists, we turn to one of Hollywood’s go-to moves – free IP!

Genre: Fantasy

Premise: Dorothy Gale and Alice meet in a home for those having nightmares and embark on a journey to save the imaginations of the world.

About: This script made last year’s Black List. The script was involved in a bidding war and eventually got gobbled up by Netflix. This is an intriguing purchase in that this film will cost at least 120 million dollars (probably more). It’s also an indication that Netflix is now poaching on film studios’ favorite material – old IP. The writer, Justin Merz, is an English teacher.

Writer: Justin Merz (based on the characters created by L. Frank Baum, Lewis Caroll, and J.M. Barrie)

Details: 114 pages

When in doubt about what to write next, turn to the classics.

Cain and Abel, Shakespeare, Wizard of Oz, Frankenstein, The Count of Monte Cristo, dare I say ROBIN HOOD(???) – I just did. I said Robin Hood. But it’s true. Hollywood never tires of these stories because they tick two of the most important boxes in production. They are KNOWN TO EVERYONE and they are FREE TO LICENSE. That’s profit on both ends, baby. And yet, Hollywood’s been screwing up the formula. They’ve got the Robin Hood Problem. The Pan Debacle. The Frankenstein Atrocity. And when was the last time someone gave us a good Shakespeare adaptation? It’s been so long, it’s starting to feel like it was back when Shakey was alive!

I suspect that there are so many options bouncing around our field of vision these days that if we whiff even a HINT of dust on a movie, we’re out. “We’ve seen this already!” we scream to our glowing portals. Only for the studios to be confused when we don’t show up to their latest CGI debacle. The trick to writing in this genre is you have to make it feel new. That’s the only way to wipe the dust off. And hence I give you Dorothy & Alice, a script that will attempt to reinvent a story we know by combining TWO tales into one. Let’s see if it works…

It’s 1901 and an 18 year-old Dorothy keeps having nightmares where she tries to get back to Oz but can’t find it. UNTIL NOW. Dorothy digs under some dirt, finds the yellow brick road, which leads her to someone named Ozra – protector of the Emerald Tower – who informs her that she needs to find something called THE DREAM STONE stat! If she doesn’t, it’s likely that the Red Prince will. And if he gets the stone back to his mommy, it will allow her to destroy any reality – Oz, Wonderland, Neverland, even Earth!

Dorothy’s cool uncle (her aunt has since died) believes that her crazy dreams are real and sets her up with a dream specialist who lives all the way out in London. Once there, Dorothy stays at a special hospital for girls who have wild dreams like hers. She’s thrilled when the head doctor, Dr. Rose, believes that Oz exists. But the good vibes don’t last. A crazed former patient named Alice pops in and recruits her to come to Wonderland where it’s believed the Dream Stone is located.

When Dr. Rose learns that the girls have escaped, she sends two of her men to neighboring Neverland through a Matrix-like contraption that allows people to jump into the dream world at will. Dorthy and Alice travel across the magnificent Wonderland, only to get picked up by Princess Tiger Lilly, who whisks them off to Neverland. Once in Neverland, the Red Queen arrives looking for the dream stone and, wouldn’t you know it, the Red Queen is Dr. Rose!!! Spoiler alert. From there it’s a battle to secure the dream stone and the good guys win and it’s all happily ever after………. or is it?

So here’s the deal.

I can’t stand scripts that are one giant CGI fest. For starters, when it comes to worlds this unique, it’s hard to imagine what we’re looking at based solely on words on a page. But, more importantly, when you write these movies, you risk slipping into CGI dependency, where the answer to your story problem becomes an enormous set piece on top of a giant rose with 50 foot monsters attempting to eat your hero.

The irony of a scene like this is that it’s both imaginative and unimaginative all at once. Sure, we’ve never seen it before. But we’ve seen enough stuff like it where it isn’t interesting. It’s much harder, and more rewarding, to come up with an emotionally resonant character-driven scene. But the more you fall into “GIANT CGI MOVIE MINDSET,” the less likely you are to go with that option.

I actually liked how this script began because it was character driven. I thought it was a really interesting question the author was posing – What is your life like three years after going through an incredible experience that nobody else believes you went through? Imagine how frustrating that must be. And when you add the death of Auntie Em, it makes Dorothy’s situation even more sympathetic.

I WANTED TO WATCH THAT MOVIE.

I even liked it once we got London. Again, it was because the writer was forced to write real things. Just to be clear about what that means – I believe that readers are attracted to things that they can relate to in their own lives. That’s a big reason why Harry Potter is so popular. It mirrored the school experience everyone goes through. When we get to London in Dorothy and Alice, we’re still dealing with real world things like settling into a new place and meeting new people.

Once we get to Wonderland, all of that goes out the window. It’s one CGI experience after another. And while I understand that a lot of this is inherent to the concept (it’s called WONDER-land, so there has to be plenty of wonder), that doesn’t mean you throw out the tool that helps the reader relate to what’s going on. You can ALWAYS use that tool, no matter how insane the world you’re writing about is. In Raiders, it’s the broken relationship between Indiana and Marion. Who hasn’t had to navigate a broken relationship before? It’s the thing that reminds us these people aren’t that different from ourselves.

I don’t know what the flaw or conflict or relationship issue any character here is going through. All I knew was that every ten pages, there’d be a new creature. That’s lazy. Not engaging.

Something that amazes me every time I think about it is the climax of The Matrix. It’s the epitome of the argument that character is more important than spectacle. The climax of The Matrix takes place IN A HALLWAY. The background is WALLPAPER. Think about that for a moment. That’s how minimalist the movie is. And we’re talking about a film that pioneered special effects. Yet the final battle is as simple as it can get.

I try and tell every writer I can about this scene because it’s more than just an example. It’s a way of thinking. When you’re struggling with your script, the solution is rarely to come up with the best action or chase or explosion scene ever. But rather, it’s to explore who your character is and how you can use this experience they’re in to test them.

A lot of you are probably confused now because I’ve gone on this whole rant yet Dorothy And Alice sold to Netflix. So why did it sell? I don’t know. But I can hypothesize. My guess would be that Netflix wants to get into the IP game. And going with free well-known IP is one of the easiest ways to do it. The writer DID come up with a new take, which is to combine two worlds. I suspect that that also had something to do with it, as it gives them unlimited options for sequels if the film does well. And the script is written well. I’m not saying this script is bad by any means. It provides spectacle if that’s what you’re looking for. My argument is that this stuff doesn’t resonate unless you prioritize character over spectacle. And I didn’t see that here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As a counter-argument to my review, I will admit that these kinds of scripts are good for writers who want to show that they have the ability to write big set-piece laden Hollywood screenplays. The scripts themselves don’t often sell. But if you can be consistently imaginative, and write even two REALLY INVENTIVE set pieces, that could get you an assignment on one of these effects-heavy projects. — HOWEVER, if you do that AND YOU NAIL THE CHARACTERS, you will be desired by every major studio in town.

This is as close as we get to flashy spec sales these days. A writer writes a short story, gets Ryan Reynolds attached, and a bidding war erupts!

Genre: Horror

Premise: A young resident at a psychiatric hospital attempts to diagnose its most dangerous patient.

About: And now for something different. Today we have the wonderful success story of a writer who posted his short story on the subreddit “Nosleep” two years ago and last week, found himself teamed up with “it” Warner Brothers’ horror producer, Roy Lee, and Ryan Reynolds, to turn the tale into a movie. Right now Reynolds is listed only as Producer. But it’s hard to believe he won’t want to play the juicy role of “Joe,” the titular patient driving the story, by the time cameras get rolling. Jasper Dewitt is experiencing that rare “came out of nowhere” moment that every writer dreams of.

Writer: Jasper Dewitt

Details: roughly 60 pages

I absolutely love success stories like this. In today’s Hollywood, the majority of breakout stories come from within. Most of the writers you see credited on studio movies came up through the system. They never had a true “name in bright lights” moment. So it’s fun to see that it’s still possible, even if these breakout moments require some unique twist. Writing a great screenplay will always get you noticed. But being found in some random corner of the internet carries with it that “rags to riches” story the trades love to write about.

Patient’s success also embodies the spirit of what I’ve been pushing for the last couple of years. Which is that you shouldn’t limit yourself to just writing screenplays. And you shouldn’t be trying to get noticed solely through traditional channels. The end game is to get noticed. Therefore, you need to be taking a “whatever means necessary” approach.

Just 25 years ago, it was impossible to get read. Almost literally impossible. Think about if you had a screenplay but no internet. How would you even begin to get people to read your stuff? You’d be lucky if three people read your screenplay in a year. Now we have entire websites dedicated to you being able to promote your work. Take advantage of that. Cause stuff like what happened to Dewitt can happen to you.

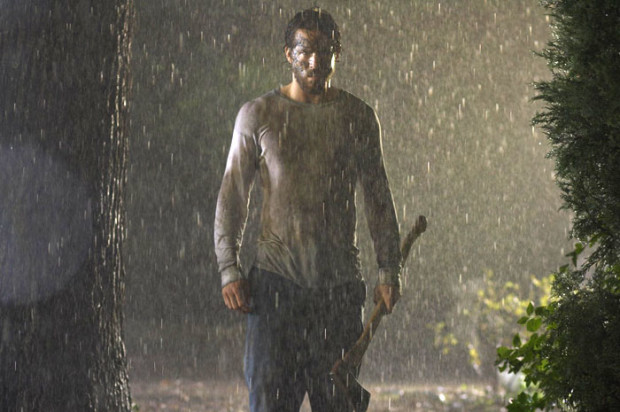

“Patient” is written in a first person voice so as to take advantage of the medium where it was published (Reddit). Their subreddit, “Nosleep” has a rule by which every story written there is “true.” Therefore you need to treat it as such. Our hero, Parker, has just started his residency at a psychiatric hospital and all he hears about is the mysterious patient, “Joe.” Joe is legendary due to the fact that everyone who speaks to him either quits, goes insane, or commits suicide. Being your typical ambitious doctor, Parker wants to be the one who cracks him.

It’s by no means an easy goal. There seems to be an intricate web of levers one must navigate in order to get permission to even get inside Joe’s room, much less try and diagnose him. So, at first, Parker goes through Joe’s old files, where we learn that Joe’s been here for over 20 years, since he was six years old, and was committed for being convinced that a spider-like monster lived inside his bedroom walls.

By the time Parker finally convinces the president of the hospital to get a crack at Joe, he’s bursting at the seams. But Joe isn’t anything like Parker expected. He’s skinny and meek and completely lucid. He tells Parker that everything Parker’s heard about him is a lie. That he hasn’t hurt anyone or convinced anyone to hurt themselves. But, rather, his parents are disgustingly rich, and, at the moment, he’s the hospital’s biggest source of income. As long as he’s here, they’re getting rich.

Parker becomes so convinced that Joe is being taken advantage of, that he plans an elaborate escape to free Joe. However, on the night of the escape, he’s swooped up by the orderlies and brought to the president, who informs him that she knew about his escape plan all along. “How?” Parker says. “Joe told me,” she replies. And it’s from here that Parker learns Joe is a lot more complicated than he expected. And maybe he should’ve heeded the advice he got about Joe from the beginning – to stay as far away from this psychopath as possible.

I have mixed feelings about this one.

We have a clear protagonist goal in place: diagnose and save the patient.

But is that goal strong enough to power an entire movie?

That’s the first struggle I had.

The second was padding.

Early on, Parker tells us he’s going insane due to the experience he had with his patient, Joe. Then makes us wait forever before he brings us into Joe’s room. I get it. The writer’s milking that suspense. But I didn’t feel like he’d earned the right to make us wait that long. Okay, you’ve established that the patient is weird. Let’s get to him already.

One of the worst things in storytelling is padding. If it feels like the writer is writing stuff just to pad up the page length, I go insane. And while I understand you need to build up a world before you can exploit it, you only get so much leeway. If I were reading this as a screenplay, I would’ve given up on it during this section.

And I thought about that while it was happening. Why is it, in this particular scenario, that I don’t care enough to get to the good stuff? I realized it was because the main villain, Joe, was becoming more and more obvious the more we learned about him. He made this nurse commit suicide. He assaulted another patient. He scared a guard. WE GET IT! HE’S NOT A GOOD GUY! lol It was all so obvious. Had we been given info about Joe that was actually surprising, I might’ve changed my tune.

This is probably why, once Parker finally talks to Joe, I got onboard. Joe, it turns out, is the opposite of what we’ve been told. I liked that Joe was making sound arguments about being set up, namely that his parents were rich and he was a paycheck for the hospital. All of these rumors about committing suicide or assaulting patients, were lies made in order to keep the gravy train rolling. This set up a legitimately compelling mystery: Which side is telling the truth?

Now Parker has to go back and forth between the two sides to come to a conclusion. It’s during this time that a new variable comes into play – the monster in the walls that supposedly drove Joe here in the first place. I like when stories do this – pose multiple questions – as it gives us more reason to keep reading. Now I’ve got two things I want to figure out.

The story’s featured scene is when Parker visits Joe’s old home so he can inspect the bedroom where the monster supposedly attacked him. I don’t know why but I’m a sucker for the old, “remove the rug and find an anomaly on the floor” development. I fall for it every time. And we get an appropriately kick ass climax to the scene when Parker’s had enough and takes an axe to the walls.

At this point, I was in “worth the read” territory, only to be yanked back to “wasn’t for me” when the author attempts to button up his story with a Sixth Sense level twist. I’ve read the twist several times now and I still don’t understand it. Even after going down and reading some of the comments, it’s confusing.

I’ll say this about good twist endings. They require more rewriting than anything else in storytelling. That’s because they need a series of setups that were put in place throughout the script. And you need to tweak those setups and the ending repeatedly so that when the payoff for those setups finally arrives – our twist – we understand what’s happened immediately. If the audience asks, “Wait, what?” after this moment, the twist didn’t work. And that’s very much how this twist felt. It was a “Wait, what?” twist.

“Patient” is a pretty good story. It’s fun in places. But it seems to be lacking that je ne sais quoi that puts movies like this over the top.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The twist ending is one of the most tempting items on the writing menu. However, think about how many truly great twist endings there have been in cinema history. Can you think of more than five off the top of your head (no, I’m serious – list as many as you can in the comments section – no googling!)? My point is, only write a twist ending if you’re sure it’s effing great. Otherwise, write the ending that best suits your story.

No post today. Instead, I command all of you to write for FIVE HOURS this weekend. Find the time. Work on your script. Or an outline. Or start something new. However you want to parse it. As long as you’re writing. If you need a break, come back here to discuss the newest Avengers trailer (what?? no action scenes???). You can also read last week’s big sale in town, which happened to be a story someone wrote on Reddit’s “No Sleep” subreddit. It’s about a doctor who works in an insane asylum who tries to connect with a disturbed patient. Another example that you can find success in a myriad of different ways. I’ll be reviewing that on Monday. Seeya then!

As we inch towards an Avengers Infinity War Part 2 trailer, the Russo brothers, who directed the film, have been giving interviews. And one of their recent statements made me look up and say, “Wucchu talkin’ bout Willis?” Apparently, the Russo brothers aren’t fans of the two-hour storytelling format known in most corners of the world as the “feature film.” Here’s what they had to say: “We are in a major moment of disruption. The two-hour film has had a great run for about 100 years but it’s become a very predictive format. It’s difficult, I think, to work in it. … It’s sort of like saying, ‘We all like sonnets, so let’s tell sonnets for 100 years, as many ways as we possibly can… I’m not sure that this next generation that is coming up is going to see two-hour narrative as the predominant form of storytelling for them.”

That’s a bold statement. The two hour movie is dead? Have I been transported to another dimension? Actually, I admit to having similar thoughts over the last couple of years. One of the most annoying things about going to movies these days is that I always know what’s going to happen. Or, even if I don’t, I have a pretty good idea. The way the 2-hour 3-Act movie is set up necessitates that only a finite number of things can happen. I mean, if you set up a goal in the first act, the end of the movie is either going to be our hero achieving their objective or failing at it. If it’s a big Hollywood movie, they’re probably going to succeed. If it’s an indie movie, it’s not always obvious, but you usually have a good idea based on the tone of the film.

So I’m left to ask, “Why DO we still tell movies in a two-hour format?” Well, a big part of it is that movies have to be at least 80 minutes to be shown in a theater. This is so you don’t go see a movie and 40 minutes later the lights come up and you feel like you’ve been ripped off. The two hour format also seems to be the baseline for how long an audience is willing to sit down and watch a piece of cinematic entertainment before they start shuffling about and getting impatient. Hence why films are around two hours long. But I do think it’s a fair question to ask: Is this format the way it is because it’s the best way to tell a story or is it the way it is because we’ve gotten so used to it that we haven’t bothered to come up with anything else?

The argument towards change seems to be coming from the explosion of streaming entertainment. This new outlet has begun to tell stories in ways they haven’t been told before. Black Mirror has given us a series of one-hour films. Maniac is an 8 hour movie. And it seems like we’re only at the beginning of this experimentation process. Hulu just announced a John Grisham “universe” whereby two shows will be made side-by-side and tackle the same story from their own individual perspectives. Meanwhile, sites like Youtube are popularizing the 12-15 minute format, even if right not it’s being utilized mostly for real-life content creators. So TV/Streaming/Internet seems to be driving this “the two hour movie is dead” narrative.

But let’s not kid ourselves. TV still has its own story problems, namely the “never-ending second act.” Almost every story starts with a problem or issue that needs to be resolved. For example, with Lost, it was “We need to get off the island.” Or with Breaking Bad, it was, “Get my family taken care of before I die.” This ensures that the first few episodes (or, if a show is really well-written, the first few seasons) begin with a giant push. But inevitably we get to a point where it feels like we’re spinning our wheels. The new shorter-series streaming projects have less of this. But they’re still there. That’s one of the powers of the 2-hour format. Is that everything has to be decided by the end of the film. So there’s an amazing amount of momentum propelling the story forward. It’s a rush as opposed to a slow drip.

Still, I think there’s something to what the Russos are saying. The two hour feature storytelling format has become embarrassingly predictable. There are only so many ways you can remix the 3-Act structure. Every good story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Sure, you can try and pull some Tarantino shit (“Every story should have a beginning, middle, and end, but not necessarily in that order”), but for the large majority of the writers who try that, their scripts come off less revolutionary than they do messy. Playing with time requires a deft touch. And it’s usually a gimmick to begin with.

I suspect the fate of the 2-hour film is going to play out over the next decade. The feature world will skew more and more towards spectacle, which means the majority of the non-Marvel movies we watch will be at home on streaming services, where there are no restrictions on time limit. And that’s where more and more chances will be taken. It’s going to take young writers and filmmakers who grew up without these hard-limitations in mind to discover different ways of telling stories. Despite that, I don’t think the core of how we tell a story will change. There will always be a beginning, a middle, and an end – a setup, a conflict, and a resolution. That’s how stories have been told for two thousand years. So I don’t see this “the two hour movie is dead” proclamation as doom-and-gloom. Maybe more of an evolution. And I wouldn’t mind that if it eliminates movies like Mortal Engines and Artemis Foul. Would you?