You wanted an update. You got it! There are hundreds of entries, possibly over a thousand (a couple hundred came in last night at the last second). So I will be reading these over the next month. I will be announcing winners (if any) on Monday, March 11th. In the meantime, hang tight!

Spielberg swoops in and locks up a short story from the /NoSleep subreddit, a growing breeding ground for movie projects.

Genre: Horror

Premise: After his friend takes his life, a young man teams up with the girl being blamed for the suicide to look for a mythical spire popularized in a local ghost story they believe to be the true cause of the death.

About: We have ANOTHER short story sale – this one picked up by Amblin! Steven Spielberg’s company! This is another sale stemming from the /Nosleep subreddit. “It” producer Roy Lee will co-produce. The most amazing thing about this sale is that the story was posted five years ago! Never give up, right? You can read the short story here.

Writer: Tony Lunedi

Details: 8 pages

How many times do I have to say it? Short stories are the new spec scripts. Evolve or die. Okay, maybe keep writing screenplays. But if you aren’t expanding your portfolio into shorts at this point, I don’t know what to tell you.

A couple of days ago in the comments section, one of you pointed out that you’d queried everyone in town and only gotten back two replies. Another reader replied to this comment that the days of cold querying were over, that most people in town expect you to use online resources to get noticed (places like Scriptshadow, the Black List, social media, self-publishing, /Nosleep). They let real people do the vetting process for them since they no longer have the time or patience to do so. I don’t know if we’re all the way there yet. But we’re close. And it makes sense. If you’re serious about this profession, you’ll figure out a way to get your work seen. And when your skill level lines up with your marketing savvy, someone will take notice.

That last part of the equation is crucial. A lot of writers get their stuff out there, and when nothing happens, blame the delivery method. If people aren’t responding to your work, there’s a good chance something’s wrong with your writing. If you’ve got the dough, you can hire people like me (writers often send me a script and say, “Tell me what’s wrong with my writing so I can improve it”), or you can take the feedback you get from the public, create your own online curriculum, and get better in those weak areas. But you never want to blame “the system” for your lack of success. Once that happens, you’ve sealed your fate, because it means you’ll stop trying to get better.

“Robert Edward Kennan killed himself in the Fall of 1999…” That’s how our unnamed 17 year old narrator starts his story. After Robert leaves two suicide notes, one to the beautiful but cold Alina, the other to mutual friend Fletch, rumors spread that Robert killed himself because Alina rebuffed him.

Our narrator regales us with his love for scary stories, particularly ones steeped in local New England lore. There is one in particular, The Widower’s Clock, that chronicles a clockmaker in the early 20th century who built an elaborate clock, the kind that appears on giant churches, complete with life-sized dancing figures. When he caught his wife sleeping with another man, he killed them and placed each of them inside these dancing figures. The clock never sold, and the rumor is that it is buried on one of the many uninhabited islands off the coast of New England.

This is relevant because Robert indicates in his suicide letters that he heard the bells from the clock and followed them to their source, where he witnessed something horrifying. Alina believes if they can prove the clock exists, she’ll be off the hook as the cause of Robert’s suicide. So our narrator joins her, Fletch, and the only other person who knows more about the lore of this area than he does, the tall and gangly “Scary Kerry,” to locate the clock. But when he begins to fall for Alina himself, he loses crucial perspective, putting the entire pursuit in jeopardy.

This is SO MUCH better than that abysmal piece of garbage we had to endure the last time a short story sold. Whereas that story was marketed exclusively to literary types more interested in metaphors and symbolism than logic and narrative focus, today’s writer is focused solely on providing an entertaining story. And boy does he succeed.

The thing I’ve learned about horror stories is that they don’t jump into GSU (goal, stakes, urgency) right away. They begin with a mystery. Eventually that mystery requires our characters to try and solve it (and GSU appears). But before that, we’re pulled in by the mystery itself. The simple question of “Why did Robert commit suicide?” is a good one, since the implication is that his death is connected to an old ghost tale.

And not just any ghost tale, but a creepy one. Arguably, Lunedi’s most prominent skill is detailing these old ghost tales. He doesn’t stop at the facts. He paints a picture. I loved, for example, how the clockmaker finished this Magnus Opus of his, had two major bidders on the line, only for the Depression to hit, ensuring that the clock would never sell. These are the details that turn average stories into great stories.

This detail is extended into characters as well. Nobody gets introduced without backstory that contextualizes them. Even secondary characters. For example, Lunedi doesn’t write, “I found out something was wrong on Tuesday morning when Fletch’s rust-bucket didn’t show up in my driveway like it usually did. Instead his dad arrived.” He writes, “I found out something was wrong on Tuesday morning when Fletch’s rust-bucket didn’t show up in my driveway like it usually did. Instead his dad, an air force officer nowhere near as affable as his son, was waiting for me.” It may seem like a small change, but notice the difference in the way your brain imagines this person with the first example as opposed to the second. We can SEE a former Air Force Officer. We can’t see a “dad.” A “dad” could literally be any adult male.

My biggest takeaway from this story, however, is how much effort was put into it. When you read all the other stories on /Nosleep, it isn’t that they’re lazily conceived. It’s that they’re lazily explored. These writers believe they can throw something together in an inspired weekend and blow everyone away. When you read the level of detail in this story, the way the characters are conceived and explored, the way the plot evolves, the way the prose is written – you can tell that this story was obsessed over.

To bring this back to screenwriting, I see the same problem. Writers put stuff out there that’s clearly four, five, even ten drafts away from being ready for discerning eyes. They’re so happy they finished, they want to share their work with the world. But that’s not the work that gets recognized. The work that gets recognized is the work that the writer worked meticulously on. They didn’t stop until they got every character and plot beat and line of dialogue and line of action and subplot and reveal to where they were satisfied with it. You clearly see that in Spire. I don’t see that nearly enough in the scripts that I read and would identify it as one of the major differences between amateur and professional work.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re considering writing a horror movie (or short story), consider setting it ANY TIME before the ubiquity of internet and cell phones. With each passing year, we become more connected, more available, easier to track down – all things that work against a good horror scenario. With horror, the feeling of isolation, of nobody coming to your rescue, needs to be present. And the past is the best place to find that. This story is set in 1999. I don’t think it works if it’s set in 2019. I believe this is a big reason “It: Part 1” worked. It’ll be interesting to see how they deal with this in the upcoming sequel, which takes place in the present day. I have a feeling it won’t be as scary. (As with every guideline, there will always be exceptions to the rule)

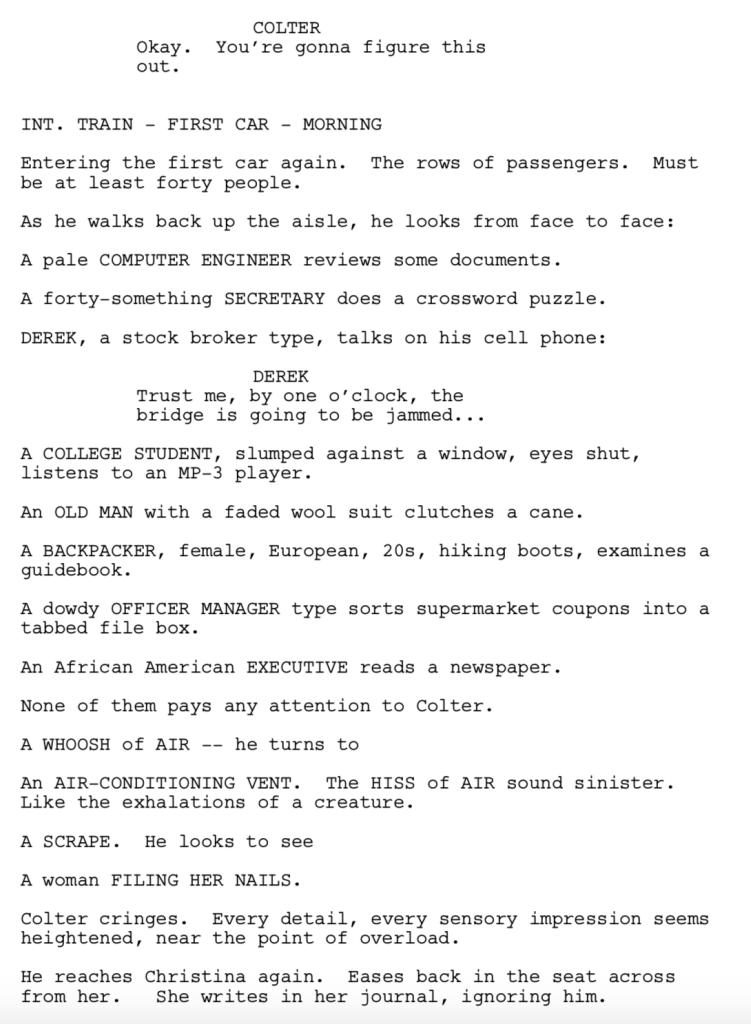

You have until Sunday, midnight, Pacific time, to turn in your first 10 pages. Send a PDF to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the subject line, “FIRST 10 PAGES.” If you don’t know about the First 10 Pages Challenge, go here. In the meantime, here are 10 pages to inspire you.

We are almost at the end of the First 10 Pages Challenge! You have until Sunday, 11:59pm to submit your entry. Send a PDF of your pages to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the subject line “FIRST 10 PAGES.” Head over to the original post to find out more about the challenge and what I’m looking for. I’ll let you know Monday (after I see how many entries I get) when – or IF – a winner will be announced. It’ll likely be no longer than a month.

Here are five of those entries. For those of you new to First 10 Pages breakdown posts, what I do is take five entries, show you how far I got, and explain why I stopped when I did. I’m hoping this information helps you craft your pages in such a way that they’ll be impossible to put down, which is the name of the game. Let’s get to it!

It’s never good when I’m confused by the very first slugline. I don’t know what “Tenement back-courts” are. Tennis courts? Basketball courts? As a writer, you never want to assume that the reader knows what you’re talking about if it’s in any way specific/unique. If I’m describing an area in Los Angeles and I say, “The Hollywood Sign,” you know what I’m talking about. If I say, “The Bird Streets,” you probably don’t. So I need to tell you what that is.

It’s important to talk about what the writer does next because it’s risky. And if it doesn’t work, you can lose the reader right away. The writer talks AROUND the setup instead of just setting the scene up. In other words, he doesn’t say, “VEA GREY searches through hanging laundry, looking for the perfect outfit.” He says, “GOLD-BROWN EYES. Searching. A scar on the bulge of her cheekbone. Tough times, but VEA GREY’S been tougher.” We’re talking AROUND the action, AROUND the introduction of the character, instead of just setting things up normally.

An argument can be made that this scene is set up like a movie. It’s almost like we’re a camera and we’re meeting this person, as well as what she’s doing, image by image. Unfortunately, a lot of readers don’t like this, myself included. We’d rather you just tell us what’s going on. I had a hard time understanding what I was looking at, so I was already on edge. And once we get to the arcade, my mind has drifted, and I’m out.

Let me remind you of the point of the exercise. It’s to hook the reader immediately. Not get all artsy-fartsy and try to impress the reader. That never works.

These pages were okay. I like the paranormal ghost hunter sub-genre, so I gave the pages a little longer than I normally would. That’s something you can’t control as a writer – if the reader likes your subject matter or not. The only thing you can do is send your script out to as many people as possible, increasing the odds that more people who enjoy the genre will read it.

There just wasn’t a big reason for me to keep reading here. The teaser was unique, which I liked. But once we got to the ghost hunting scene, it felt too familiar, and sloppy to boot. There wasn’t enough structure to the scene. What the writer should’ve done is set the scene up from the start. Build the scene like a mini-screenplay, with an Act 1, Act 2, and Act 3. Actually, that’s my best advice to pull a reader in right away, is open with a scene that’s a mini-story within itself. This is exactly what they did with Inglorious Basterds. It’s what they did with Scream. It won’t work for every script. But if there’s even a chance it will work for yours, consider it.

Oh yeah, and get a proper screenwriting program! Readers have been known to blacklist writers with text this light.

This scene moves too fast. Remember that hooking a reader doesn’t mean racing through a scene at breakneck speed. In fact, it can mean the complete opposite. In the case of this script, my first question is, why are they here? They’re driving through this place – Wildland Ranch – that appears to be special, like a backwoods Disney Land. Yet they don’t appear to be going here. The way they’re talking to each other, you’d think they were on their way home. It’s odd.

Then, when this woman pops out of nowhere, everything occurs way too fast. When something this jarring happens – a woman appears in front of your car out of nowhere – you need to take your time. It takes all of three lines from “My baby’s missing, will you help me,” to our heroine agreeing to. I mean come on. We’re in the middle of nowhere. This woman seems off. There would be questions. Erin and Roy would probably fight about it awhile. Bottom line: The writing feels rushed. It doesn’t seem like the writer has thought through the scenario. And for that reason, I’m out.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with these pages. Nothing. But there’s nothing exceptional about them either. Let me remind you what the exercise is again. It’s to hook the reader. It’s not to write something that’s “fine,” or even “ better than fine.” It’s to GRAB THE HELL out of the reader and make it impossible for them to stop reading

Starting your script with a murder is an above-average opening scene choice. A dead body gets the juices flowing. We’re curious who this is, what happened. A goal is set up right away – solve the murder. The problem is, I’ve read hundreds upon hundreds of scripts that have started with a murder. What makes this different? That she’s a celebrity? I’ve read tons of celebrity murders as well.

You have to find a way to make your scene unique. Here’s the opening of an early draft of Silence of the Lambs, which covers another familiar setup – an agent engaging in a dangerous hostage situation. Ignore the bold text. Someone did a bad digital PDF transfer from the original script.

Would you keep reading? I would. Notice that by making a slight tweak – the unexpected reveal that the suspect’s finger is taped to the trigger in a manner where he’s unable to use it – gives the scene a fresh feel (not to mention puts our hero in serious danger). Remember, the audience has seen everything. You need to work your ass off to give them something they haven’t.

Wow! I made it to the end of another ten pages. Sweet! Okay, why did I read all ten of these pages? There’s nothing spectacular here. But much like Bill’s pages from last week, there wasn’t any reason to STOP READING. The writing is achingly simple. And that’s a good thing. Unlike the first entry, I’m not trying to piece together the simple actions of my main character. Everything is clear as day.

Another thing is that in all the scripts I’ve read, never has one started with a woman teaching immigrant women how to wear their bathing suits properly so they don’t get arrested. The value of originality in a world so saturated with content is high. That’s why I read past the first page.

The writer then shifts to a marriage ripe with conflict. It’s not over the top but we sense it in their phone call. Remember that when you establish conflict, there is a subconscious need for the reader to keep reading to see if that conflict gets resolved (if she smiles and says “okay,” there’s no mystery to this marriage). From there we get this fun little wallet-stealing fiasco where we’re wondering if Alice is going to come out victorious or not. What a great character, too. Who doesn’t like a woman who puts her reputation on the line to do what’s right?

I have to admit that I don’t know where this movie is going from here. But I like this feisty main character so I’m keen to find out. What did you think?

Genre: Dramedy

Premise: (from Black List) The longtime assistant of a famous singer must navigate the rocky waters of the LA music scene to make her dreams of producing music a reality.

About: Today’s script finished JUST OUTSIDE the Black List’s top 10. Flora Greeson is just getting started with her career. She scored a rewrite job on the Elizabeth Banks project, “When Prince Made a Chambermaid His Queen for a Day,” about an MTV contest in the 80s where a fan got to be Prince’s date for a night. This is the script that got her the gig.

Writer: Flora Greeson

Details: 99 pages

Music flicks are hot right now, people. The double-hit whammy of Bohemian Rhapsody and A Star is Born has whet studios appetites. Today’s script tries to take advantage of the craze. Let’s see if it succeeds.

26 year-old Maggie Sherwood is an assistant to one of the most important singers of the last three decades, Suzanne Wilson (Aretha Franklin, Mariah Carey, and Whitney Houston rolled up into one). Maggie has finally graduated from running errands to producing Suzanne’s current project, a Greatest Hits live album.

But Maggie is frustrated with Suzanne. She thinks she should be releasing new music, not going back to the well, even if that well is bottomless. Suzanne is reluctant to the idea, which sends Maggie off in search of someone new she can produce. One day, while in the drug store, she bumps into the impossibly handsome David, a great singer held back by an anxious streak. Maggie tells him that if he gives himself over to her, she can make him a star.

Naturally, she starts falling for him, and their impromptu musical assignments begin interfering with her assistant job. Suzanne has a giant promotional concert for the Live album, and she needs Maggie now more than ever. Specifically, she needs a hot young act to bring some millennial attention to the concert. I think you know where this is headed.

Maggie orchestrates some last second shenanigans to make David the act. But while Maggie assumes Suzanne will be the tough sell, it turns out it’s David. Will she be able to convince him? Or will a last second bombshell ruin everything?

I know what everyone who just read this summary is thinking.

“That sounds like the most cliche plot ever.”

And you’d be right. We’ve seen this plot time and time again. But here’s why it’s still a good script – because Greeson nailed the execution. It wasn’t a slam dunk. But she got most of the pieces right. Which made for a highly entertaining read.

Look. We all want to be the next Tarantino, or Jordan Peele, or Diablo Cody, or Charlie Kaufman – that writer with an impossibly unique voice that the town goes bonkers over. But that’s not the only way to break in. You can work in this business a long time by becoming a Screenwriting Execution Nerd – someone who knows how to get all the pieces right. It’s the difference between Tom Brady and Eli Manning. Tom Brady is Tarantino. He does things nobody else can do. Eli Manning is Derek Kolstad (the writer of John Wick). He’s more of a game manager. But guess what? Eli Manning won 2 Super Bowls. Same thing with Kolstad. He built a major franchise. So don’t hate on execution. If you can learn how to nail this unique skill that is screenwriting, people are going to hire you.

Covers executes three things really well. For starters, the characters in this script are fun and vibrant. Remember that if you can make us love your characters (specifically your main character), half your job is done. That’s because audiences like following people they like, even if the story is flawed. Maggie gets shit on all day, but keeps plugging away. She’s got a good sense of humor about her position. She’s also talented at what she does. These are all things you would admire in a real life person. So of course you’re going to like them in a fictional one.

Even Suzanne, who plays second fiddle in the story, is interesting. She’s riding on the success of her past instead of taking a chance and trying to do something new. So there’s conflict there. Where there’s conflict, the audience will want to keep watching to see if that conflict is resolved (in this case, whether she’ll record new music or not).

Next, the plotting here is STRONG. We’re always moving forward. The first scene of the script has us dropped into our heroine running around in preparation for her boss’s party. And it never stops. By creating this GOAL of the Greatest Hits Live Album slash promotional concert, we always have something we’re moving towards. That’s how you write good plots. The characters are moving towards something important.

Finally, Greeson KNOWS HER SUBJECT MATTER. She has a passion for music. When I started writing, I didn’t think this was important. Eventually I realized that the name of the game was pulling the reader into your world. Once they’re in your world, you have them. So the more you know about the subject matter you’re writing in, the easier it is to pull people into your world. These characters in Covers are able to rattle off artists and albums and songs the way only people who live in the music world can. Not to mention the technical things like what a recording session looks like, or what a day in the life of a real music legend looks like. All of that felt legitimate, which made me believe in the story.

When you don’t know your subject matter, everything you write is a copy. For example, if you’re writing a cop movie and you’ve never researched a cop’s job, you’re probably going to write the character based on some other cop character you saw in another movie. And don’t get me wrong. Sometimes you can get away with this. All I’m saying is that when you’re writing about a world you REALLY understand, it makes a difference. I fully trusted that Gleeson knew this world inside out. The details are way too specific for that not to be the case.

The reason Covers doesn’t get a higher score from me is, one, it’s an unoriginal plot. You can’t escape that. You can only wow someone so much with familiarity. And two, there’s a late twist in the script that’s borderline disastrous. It’s such a misguided choice that it almost sent me into ‘wasn’t for me’ territory. I was so mad because I wanted to celebrate the power of great execution with a high score. But I can’t let this ending go. I won’t spoil it but feel free to talk about it in the Comments Section with spoiler warnings.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is going to sound obvious but when it comes to being a Screenwriting Execution Nerd, you need to know how to make plots move (a complete command of the 3-Act Structure), you need to know how make heroes likable (understanding the traits that make human beings likable in general), and you need to know how to add depth to characters (through inner conflict or flaws). If you can’t do these things, you need to have an amazing voice, like Tarantino or Diablo Cody. Otherwise, why would somebody hire you?