It’s easy to tell if a movie’s not going to work. You watch the trailer and instantly sense that something is off (check here and here for exhibits A and B). You don’t always know what it is. But you know you’re not going to waste 2 hours and 15 bucks of your life on it. For the average moviegoer, this reasonless choice is fine. But the aspiring screenwriter must know why every marketed release fails so that they don’t make the same mistakes themselves. And yes, you can often identify giant screenwriting mistakes right there in the trailer. So today, I’m going to take you through 15 failed films and the screenwriting reasons why they bombed. Let’s get into it.

Downsizing – It’s unclear what the point of the movie is. After our hero shrinks, what’s his goal? What’s the story’s destination? For example, when I watch Infinity War, I know the goal is to stop Thanos. That point is clear as day. These trailers displayed no point to the story. So it wasn’t surprising, then, that the movie didn’t have a point either.

Tomorrowland – The premise promises a movie that never arrives. You tell us a movie is about Tomorrowland, yet we barely spend any time there. Not only that, but Tomorrowland is lame. If you’re going to promise us something, make sure your script delivers it.

Logan Lucky – It’s a genre-less movie. Young writers commonly assume that genre doesn’t matter. Despite all his experience, Soderbergh keeps making the same mistake as well. You have to write in a genre or sub-genre that has a proven track record of turning a profit. “Wacky indie dark comedy heist” is not a genre that’s ever proven to be successful. So of course the movie didn’t catch on.

127 Hours – Just because something happened in real life doesn’t make it a movie. A movie still needs movie-like elements to work. Having only one character stuck in a visually unappealing rock crevice… there’s nothing cinematic about that. Nor is it a situation that lends itself to 2 hours of dramatization. Maybe you could make a 20 minute short about the subject (at most). But the point is, just because something dramatic happened in real life doesn’t mean it’s right to turn into a movie (see also: Sully).

The Five Year Engagement – I don’t know if this movie is any good or not. I never saw it. The reason I didn’t see it? The title. This shows just how badly a terrible title can hurt a film. A title needs to be either creative or clear. This is neither. It slams you over the head with its bluntness yet leaves you confused. So it’s a movie about… a sort of long engagement period? Why is that funny? Why is that topic worthy of a movie?

Inside Llewyn Davis – An example of how a miserable main character can destroy any chance of drawing an audience. Every hero must have something about him we can root for. This character had nothing.

The Place Beyond The Pines – The Place Beyond the Pines is what happens when a writer writes to impress film school classes as opposed to real people who go and see movies. Sprawling, unfocused, hyper-serious, long. You can write films like this if you want. But don’t expect anyone besides hardcore cinephiles to like them.

Tully – The concept is simply too small. A mother gets help raising her children. Um, okay. The only thing marketable about this movie – its twist – can’t be marketed. So what’s left?

Foxcatcher – Your script can be slow. Your script can be depressing. But your script cannot be slow and depressing. People typically see movies to escape reality and be entertained. To give them something that embodies the opposite of that is a risk that always ends in failure.

Ghostbusters – Tried to force an agenda on audiences at the expense of telling a great story. If you start putting agendas first, whether they be social, political, personal – the movie comes off as a commercial for your way of thinking rather than a piece of entertainment. Audiences are too savvy for that.

Valerian – “Everything-and-the-Kitchen-Sink” Syndrome. There isn’t any focus. Only a desire to throw as much crazy as possible at the screen and see what sticks. Every movie, even sprawling fantasy or sci-fi, must feel focused in some way. Without a strong story engine and clear goal, scripts like this can quickly descend into messes, which is exactly what happened.

Draft Day – Outside of boxing, fictional sports movies are almost always bombs. People who go see sports movies want to feel like what they’re watching happened. Of course, it didn’t help that both the director and lead actor constructed what was originally a fast-paced fun script and turned it into something that plays to the 80-and-older crowd.

Sex Tape – Dated material. The worst thing you can be is late to the party on a subject matter. This is why it’s advisable to stay away from trends. Although, going off of interviews, it sounds like this was made solely because Sony Studios head Amy Pascal just learned about sex tapes in 2013. Stay current people!

The Mummy – Absolutely positively nothing new. Even Tom Cruise’s Mission Impossible films have a stunt or two that’s never been done before. This had nothing new. When you don’t have a single new thing to offer with your screenplay, why would anyone show up to see your movie?

Blade Runner 2049 – A tsunami of self-indulgence killed this one. Nearly every scene took twice as long as it needed to. Don’t fall in love with your stuff so much that you forget to keep your story moving.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The true story of how a CIA agent used his contacts he made in the agency to sell explosives to Libya after he was fired.

About: This script made the 2013 Black List and got Matthew McConaughey attached half a year later. Unfortunately, the project became a casualty of McConaughey’s busy schedule. This is one of the curses of getting a hot actor attached to your project. On the one hand, you become one of the most buzz-worthy projects in town. On the other, these hot actors are always over-booked and end up dropping out of a lot of projects. You risk becoming one of those projects. Once that happens, you’ll never regain that initial buzz again, so there’s a chance that no A-list actor signs on to your movie. Was it really that great to bring that actor on then? To avoid this mistake, you have to depend on your agents and producers. Ask them, “Is he really going to do it?” If that actor is signed on to 7 other movies, you might want to think twice about making the leap.

Details: 137 pages of boring

Sometimes you have to admit to yourself that you don’t have a movie.

You can rearrange the cards in your hand as many times as you want. But if it’s shitty hand, you’re not going to win it. I suppose you can try and bluff, which is what The Company Man attempts to do. But it’s hard to fool seasoned producers who are all too aware that one shitty movie can bankrupt their company.

And I’m not bashing the writer here, believe it or not. The writing is actually quite energetic. But where’s the story man? This isn’t a story.

Allow me to explain.

Edwin P. Wilson was a nobody farmer’s son who grew up wanting better things for himself. He fought in the end of the Korean War, then afterwards stumbled into a position at the CIA. Wilson’s job there was lame. He was, essentially, an errand boy.

Then one day the CIA director sent him to Libya, where he amassed a large network of political friends. To achieve this, he needed to operate a pretend company and do business with these politicians. However, one day, the government discovered that the CIA were torture-happy lunatics and cleaned house. Wilson got swept out with everyone else.

At this time, Libya was under extreme sanctions, and Wilson realized that even though he was no longer in the CIA, he could use his old contacts to make money. So he started selling weapons to Libya, specifically C-4. Lots of C-4.

After becoming very rich off these deals, two guys in a completely unrelated country are killed by a car bomb. The CIA believe that Wilson is responsible for this even though, it turns out, he isn’t. So the rest of the story is the US government relentlessly pursuing Wilson to link him to this murder.

I have read some all-timer boring scripts in my years. But this is up there.

The script spends the first half of its running time showing us how Wilson became an underground arms dealer to Libya. Why do I care about this? What makes selling arms to a backwater 3rd world nation that has little-to-no influence on the world stage a relevant story to follow? Why should I care that this is happening? The script never explains that. There are zero stakes to what’s going on.

Let me explain that further so aspiring screenwriters don’t make the same mistake themselves. If Wilson was selling nuclear weapons to Cuba in the 60s, during the height of the Cold War, that is a world-stage high-stakes event that is worthy of a story. He would’ve been putting the U.S. in direct danger of being blown to smithereens. But instead he’s selling C-4 to Libya so that they have a few extra explosives in their archives. Who cares?

The second half of the script focuses on how Wilson gets blamed for a car bomb killing that he had nothing to do with. So let me get this straight. The engine driving this story is whether our main character is going to be put in prison for an insignificant pair of deaths in another country that he has nothing to do with and that, even if he did, has zero global implications?

Where the fuck are the stakes?

You may answer that with: the stakes are high for Wilson, Carson. If he gets caught, he goes to prison. Yeah, but you’ve established that this story takes place on a global level. The stakes can’t just be our hero. They have to be bigger than that.

So how did this script gain traction?

Through the actor loophole.

The actor loophole is when you write a part that an actor will want to play and then who the hell cares what the plot is. The goal is to get the big actor. You get the big actor, you don’t need a plot. You’ve got a greenlit movie. And this is a showy character that I can see actors wanting to play. Wilson is cocky. He’s got a shaky moral compass. He’s got a lot of those cool Scorsese voice over lines that actors love.

But this is what drives me nuts about biopics. The writers are so focused on the main character that they don’t pay attention to the story. And there’s no story here. Waiting to see if a guy goes to prison because of some random bombing he had nothing to do with isn’t a story.

Also, I don’t think anyone wants to see these international weapons sales movies. You had that Nicholas Cage “Lord of War” movie that nobody liked. You had the more recent “War Dogs” with Jonah Hill. I get the idea behind these concepts. Ooh, it’s ironic, cuz, like, we’re selling weapons to our enemies! But that’s just a thought. It’s something you literally think about for 3 seconds, then go, “Yeah, that’s kind of interesting,” and then you’re done with it. There’s zero reason to spend 2 hours expanding that thought.

Like I said earlier, you have to be honest with yourself about if your idea is worthy of a feature treatment. The Company Man is half-worthy. It’s got the character. But it never figured out the story.

Will this ever get made? I don’t know. The actor catnip is strong with this one. That’s always a wild card. But it needs to restructure its story so there are some actual stakes. Everything here feels intensely insignificant, to the point where after finishing each page, you ask, “What’s the point of all this?”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: I love italicizing voice overs, particularly if you have a character who’s going to be talking in voice over a lot, such as Wilson. It’s a big flashy visual aid, so you know you’re reading voice over every time it starts. And it’s great for scripts like this because there will be times where Wilson speaks out loud then speaks in voice over right away. It’s great to have that visual aid that allows us to make that mental switch so we understand why the character is speaking twice in a row.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: In a post-apocalyptic wasteland, a dying man programs a robot to take care of his dog when he dies.

About: Talk about an 80s film package! This was a spec script that got a lot of heat at the end of last year, eventually landing Tom Hanks (presumably for the role of the robot). It’s being produced by Robert Zemeckis and Keven Misher AND Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment. The film will be directed by Game of Thrones director, Miguel Sapochnik. The script went on to finish in the bottom third of last year’s Black List.

Writers: Craig Luck and Ivor Powell.

Details: 110 pages

It always makes me happy to see a spec script muscle its way through a system that’s become increasingly resistant to specs. I’m hearing that Amblin is ramping up again. So between them and Bad Robot, we have two companies open to high-concept (reasonably priced) specs in the mould of today’s story.

Bios is part of the new “man and dog” sub-genre. We have the novel, “The Dog Stars,” which seems to have partly inspired this script. We have the ex-Navy SEAL stranded with his dog script, Heart of the Beast, that I reviewed a few months ago. And now we have Bios. Let’s find out where it ranks.

Two months is all it took for society to implode. That’s how long it was before the food disappeared. We’re a few years north of that now, and while there are survivors, they’re few and far between. One of those survivors is Finch, a 30-something former robotics engineer who’s been savvy enough to build a bunker into a hill.

Finch lives for his dog, scavenging a decaying wasteland for any food he can find for it. In his spare time, he puts together “Jeff,” a robot with a special direction – to take care of his dog when he dies. Oh yeah, there’s that too. Finch is dying.

His plan is anything but airtight. The robot’s programming is barebones. It’s never walked before. And worst of all, the dog hates him (their first interaction has the dog pissing on its leg).

When an unexpected super-storm rolls in (these seem common in the post apocalypse – although it’s not explained how they’re tied to all the food going bad) Finch realizes that if they don’t flee, his place will be leveled.

So he grabs Jeff and has dog, jumps in his Winnebago, and starts driving West. On the way, he teaches Jeff as much as he can about humanity and the world, hoping he’ll be ready to protect when he dies. Eventually, Jeff starts becoming interested in consciousness, hoping that one day he’ll be human too.

The group runs into a series of obstacles along the way (crashes, pursuers), each setback potentially deadly since their lives depend on outrunning the storm. (spoiler) Eventually, Finch dies, and Jeff’s schooling is put to the test. But when we realize he’s woefully underprepared, it’s only a matter of time before Finch’s dog is in major danger.

This started out great. How great? I was preparing a pre-post to announce a new Top 25 script. The first act is flawless. Luck and Powell paint a picture of a post-apocalypse that is both familiar yet unique. We’ve seen these scenes before and yet the level of detail used to describe scavenging a Walmart feels altogether fresh.

It doesn’t hurt that they have “Save The Cat” (Dog) built right into the concept. The second Finch gets home, we realize he’s out there specifically to find food for his dog. And when he feeds the starving dog with the food he found, we fall in love with him immediately. As I always say here on Scriptshadow: Make us love your hero immediately and we’re yours.

Once we realize how sick Finch is, the potential of this story levels up considerably. Finch is going to die, this robot he is going to have to travel with this dog that hates him, all in the hope of getting across country to safety.

How daring is that. Focusing a story solely on a robot and a dog. I’d never seen anything like it and was dying to see how they’d make it work. But then Finch not only comes with them, but is alive for most of the screenplay. This turned a smart and simple two-hander into an unnecessarily complex three-way relationship. Once Jeff’s “Pinocchio” storyline entered the picture, I was no longer clear what story the writers were trying to tell.

There’s still a lot to like here though. For example, I’m a big fan of adding chases to narratives. When you have something pursuing your heroes, it adds an urgency to the proceedings that gives the script energy. Usually, the chase comes in the form of cops, or the villain (Darth Vader in Star Wars). Using.a storm felt like a fresh way to incorporate the chase aspect.

Also, the script was clever in the way it dispensed exposition. Throughout the first act, I was wondering what year it was. In your average newbie sci-fi spec, that exposition would come in the form of a character clumsily saying, “Ever since the Food Wars of 2031, nothing’s been the same.”

Instead, Finch is fine-tuning Jeff, attempting to get him acting like a human. “So tell me something interesting,” Finch asks him. “Giraffes can go longer without water than a camel.” Finch chuckles. “Is that fact?” “Yes.” Finch turns to his dog. “I bet you didn’t know that.” The robot continues. “In February 2031, over 13 million people searched “interesting facts” on Google.” “Tell me something interesting about you,” Jeff replies.

There. Did you catch it? In the midst of him and this robot calibrating, we learned that it’s at least past the year 2031. This was achieved in an organic invisible way, within the context of the conversation. Remember, exposition is only bad when it draws attention to itself. As long as information is given within context, the reader won’t notice it.

But yeah, I think they missed opportunities here. Finch should’ve died at the end of the first act. They should’ve traveled on foot, not within the safety of a Winnebago. The movie should’ve been about the unresolved relationship between Jeff and the dog. And Finch needed to give the robot his own voice. That way the actor gets to play both parts.

I don’t throw these opinions out arbitrarily. All of them make the story simpler, which is what that first act promised, then deviated from.

With that said, I still enjoyed the script. I want big prodcos like Amblin to make more movies like this – give us a superhero breather every once in awhile. That makes me Team Bios, warts and all.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ]wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A neat little screenwriting trick is to upgrade a problem from bad to worse. In Bios, we learn that a superstorm is coming in and will obliterate everything within an 800 mile radius. A day later, as they’re putting together an impossible escape plan, they learn that two other storms are colliding with this storm, increasing the deadly diameter to 2000 miles. Within the span of 15 pages, we go from worried to terrified. It’s a simple tool, but very effective

Genre: TV Series – Drama

About: While companies like Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu have made high profile splashes with budgets that rival those of studio films, YouTube has released a bunch of no-budget pre-teen content that even pre-teens think is lame. But with the announcement of Cobra Kai, a TV sequel to the 1984 phenomenon, The Karate Kid, the online channel finally found themselves a buzz worthy program. The show was so well thought of within the company, YouTube put together a giant advertising campaign for it. The show comes from creator Jon Hurwitz, best known for writing the Harold and Kumar movies. Hurwitz is a giant Karate Kid fan, and thought he could bring something fresh to the property. The first 2 episodes of the season are free on YouTube now. If you want to continue watching the series after that, you need to sign up for YouTube’s premium service, YouTube Red.

Writers: Jon Hurwitz, Hayden Schlossberg, and Josh Heald (based on characters created by Robert Mark Kamen)

Details: Episodes are about 25 minutes long

When I first heard they were making a Karate Kid sequel in the form of a TV show, I curled up into a fetal position, shook my head… before leaping back up in the air, doing a crane kick, and screaming “HِِELL YES!!!”

The Karate Kid is one of the most iconic examples of a movie that shouldn’t have worked but did. It was cheesy, even by 80s standards. It was formulaic. The villain had as much depth as a frying pan. Even the title was stupid. “The Karate Kid.” Wow, bet that took a long time to think up.

But Holy Max Headroom did it work.

Why did it work? Because it got the key characters, as well as the key relationship in the screenplay, right. The smartest move Robert Mark Kamden made was making Daniel LaRusso a fighter from the start. Any other writer would’ve made Daniel a wimp. That’s the obvious choice. Since he will become a champion in the end – logically – we must make him the opposite of that at the beginning. But Daniel stands up to Johnny several times before he’s learned a lick of karate. That singular choice made us fall in love with Daniel immediately.

In addition to that, The Karate Kid nails one of the most effective story devices in movies – the hero-mentor dynamic. Every relationship in movies, whether it be love, family, work, or friendship, must begin with a level of conflict that makes us doubt that that conflict will be resolved. That’s why we want to watch. We want to see if there will be that resolution. Mr. Miagi’s kooky teachings combined with Daniel’s earnest impatience make for one hell of a friendship.

This is something all screenwriters need to tattoo onto their brains. If you can get the main characters in your script right as well as the main relationships? You don’t need to ace the rest of the test.

If The Karate Kid had an Achilles’ heel, it was its villain, Johnny. While memorable, he’s quite possibly the thinnest villain of the entire decade. I mean, he didn’t even have a last name. He’s just, “Johnny.” Which is why it’s so ironic that they’ve brought this story back from Johnny’s perspective.

That choice is nothing short of genius. I’d go so far as to say if they would’ve brought this show back through Daniel’s eyes, I wouldn’t have cared. Think about that for a second because it’s something I talk about a lot here. You have a choice as to whose point of view you’re going to tell a story from. And the most obvious point of view (in this case, Daniel) isn’t always the best.

Generally speaking, stories tend to be more interesting when someone is at the bottom as opposed to at the top. Daniel is at the top now (he has a thriving car dealership) and Johnny is at the bottom (he never amounted to anything). So it makes sense that we tell the story through his eyes.

The first two episodes of The Karate Kid follow Johnny, still living in the valley, as he navigates a series of contractor jobs.

After Johnny gets fired off one of these jobs (for calling the house owner a bitch) he gets a lucky break when his step-father gives him a small chunk of money. Johnny decides to bet it all on a new karate dojo. But not just any dojo. He’s bringing back “Cobra Kai,” the infamous dojo that wreaked havoc on the valley (and on Daniel LaRusso) so many years ago.

Johnny finds his first student in a “Daniel LaRusso” like teen who Iives in Johnny’s shitty apartment complex. Johnny fashions Cobra Kai as a return to basics. There’s no social justice here. No safe spaces. No asthma inhalers. Johnny’s going to show his students how to be tough again.

Meanwhile, when Daniel hears of the return of Cobra Kai, he pays Johnny a visit, encouraging him to rethink his decision. The place was such a negative cloud over the valley in the 80s, you could argue it was the main reason for the smog. Johnny tells him fat chance. This is the new reality. Daniel’s just living in it.

What I loved about these first two episodes was that head writer Jon Hurwitz understands the delicate balance that is The Karate Kid. For example, the new featured kid character, Miguel, is like a mini-Daniel. We see him immediately attempt to approach a pretty girl at school, showing that he’s not your average wimpy dork.

Hurwitz balances this out with the hilarious cheesiness of the property, giving us a classic Johnny late night ride through the valley, complete with angst-ridden music and a flashback montage to Johnny’s high school days.

But what really sold me is how brave this new version of the property is. It centers around its most unlikable character in Johnny, a mentor who’s the total opposite of what made the property so famous – the unorthodox but warm approach of Mr. Miagi. I wouldn’t say that Johnny is Trump Jr. But he certainly represents that MAGA mindset.

For those of you worried that this is a nostalgia bomb, well, um, duh. But not as much as you’d expect. This is due to the above-mentioned setup, which places our characters in roles that are virtually the opposite of how we originally met them.

Wth that said, if I were pushed into admitting my biggest worry about the show, it would be Daniel. His current motivation is the weakest of all the characters. He wants to stop Cobra Kai because it’s “dangerous.” Come on. Do we really believe a tiny karate dojo in a strip mall in the valley is going to do measurable damage to the community? Yet Daniel seems very concerned.

Measure that against Johnny’s motivation, which is iron tight. He needs this business to survive so that he can survive.

The significance of this imbalance is that a lot of emphasis is being placed on Daniel “stopping” Johnny. And while, of course, I would love to see them have a karate-off in the season finale, those moments only work when the motivations on both sides are sound. If Daniel’s only trying to stop Johnny because the writer needs him to, it will feel false. Once the truth of a moment is lost, that moment will always feel like it’s missing something.

I suppose they’re hoping we shift our focus to whether Johnny can navigate the minefield that is raising a family. THAT becomes his main conflict in the show, and Cobra Kai stays in the background. But I can get father-daughter family drama every night from 7-10 on the CW if I so please. The strange attractor here is the karate and the weird complex relationship between Johnny and Daniel. So I hope they figure out a way to make that believable.

Whatever the case, it’s a great sign when a company is so confident in its product that they give you the first episode (or in this case, the first two episodes) for free. They figure they as good as have your money if you watch the pilot. And you know what? They’re right. I just signed up.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of YouTube Red

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I Learned: A character’s motivation is the key towards portraying them in an honest way. If we don’t feel like a character is pursuing his goal because he needs to, you haven’t correctly identified their motivation. Daniel wanting to take down Cobra Kai because he didn’t like a gang of bullies in it from 30 years ago is movie logic, not real life logic, and is currently the show’s only weak link.

I heard Charlize Theron gained 50 pounds to play the roll of Tully in the new Diablo Cody film, which comes out this weekend in an attempt to woo you away from your 17th viewing of Avengers Infinity War. It was a good script and the kind of movie that gets you talking afterwards. So if you’re in that chill indie-movie mood, I suggest you check it out, if only to get Hollywood to make something other than superhero movies. Cause if this trend continues, I swear to you, that might be all they make in 2019.

On to today’s scripts. An interesting batch! We’ve got the winner of the “Why Your Script Isn’t Getting Picked” post in The House on Snare Lane. A good old fashioned adventure film. And we’ve got a writer who really knows how to sell a full read (“There’s a huge twist at the end of Act 2 you’ve got to check out!”). As you guys know, the rules to Amateur Offerings are simple. Read as much as you can from each script and vote for your favorite in the comments. The script with the most votes gets a read next week!

And if you believe you have a screenplay that deserves Hollywood’s attention, submit it for a future Amateur Offerings! Send me a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and why you think people should read it (your chance to pitch yourself or your story). All submissions should be sent to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

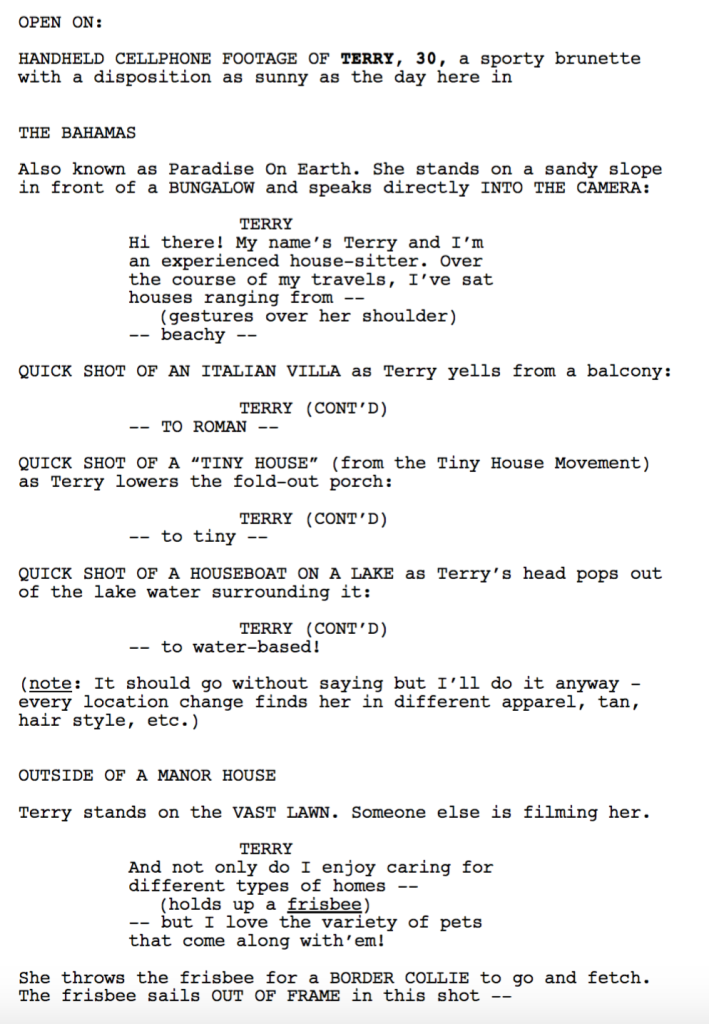

Title: Godhaus

Genre: Contained Horror/Thriller

Premise: A professional house-sitter is tormented by an omnipotent force during a week-long stay at a mountaintop chalet.

Movie Poster Tagline: VENGEANCE IS THE LORD’S, HE SHALL REPAY IT

Why You Should Read: I’m always on the lookout for odd or unique occupations, and one day I happened upon professional house-sitting. I did the research and discovered the possibilities were endless – as well as seemingly unexplored in film. So I developed the character of “Terry” but didn’t have a story to build around her… until months later, once I’d cooked up a separate idea about an Old Testament God exacting revenge on a single individual.

Then the question arose: why would our protagonist, Terry – so sweet she wouldn’t hurt a fly – be targeted for such extreme punishment?

Mix into a contained bowl, add a sprinkling of humor, a splash of twists and a dash of turns, and voilà! I’m curious to find out if Scriptshadowers enjoy the meal… or send it back to the kitchen while refusing to pay the bill and complaining to the manager about unfilmables.

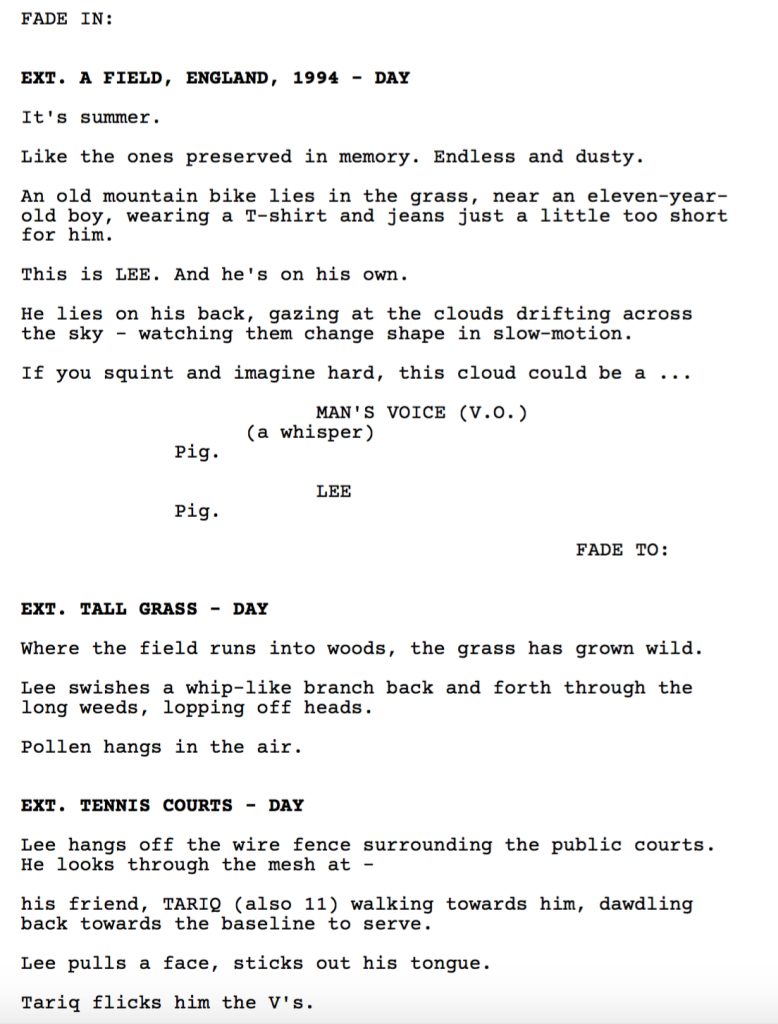

Title: That House On Snare Lane

Genre: Coming of age drama

Logline: When, on the eve of its demolition, a grief-stricken boy and his friends investigate a haunted house, they discover long-buried secrets have a way of resurfacing and … just sometimes, turning a sense of loss into hope.

Why You Should Read: Last year you wrote two articles that especially struck a chord with me. The first was a list of movies that Hollywood would like to make a new version of (not a reboot, but an original new movie that captures a similar spirit to that existing movie). The second was about the power of ‘anchoring’ elements of your screenplay in your own experience. So, here’s my take on number 6 on your list – Stand By Me, anchored to an experience in my own childhood but extrapolated … and with a sprinkle of magic added because, well, the movies should be magical, right?

Title: Blood

Genre: Historical Adventure

Logline: Based on true events. After Charles II reclaimed the English throne, he confiscated the homes of his adversaries. He also pissed off the notorious Colonel Blood. Now Blood, seeking justice and reparations, leads a crew of fellow rebel activists in one of history’s most daring heists – stealing the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London.

Why You Should Read: I’ve been writing for nearly two decades, but have only been pursued it professionally in the past few years. I’m also an actor, director, and editor… it may sound silly but I love every part of the storytelling process. I don’t generally tend toward historical pieces, but the story of Colonel Blood was so compelling I couldn’t not write it. I’m rather proud of the script, but folks around town aren’t wanting to touch a period piece from an unknown writer (yet), so I’m having a hard time getting it read. And so I come to you… Thanks for the consideration!

Title: Typee

Genre: Action/Adventure

Logline: After jumping ship on a remote island, a sailor must escape from his new captors, a fabled tribe of cannibals named the Typee.

Why You Should Read: “Typee” was Herman Melville’s best-selling book in his life time, NOT Moby Dick. The story was a hit with audiences because it was written by a man who “lived with the cannibals.” Yet for some reason, Hollywood has continued to overlook this hidden gem, which has everything a big cinematic movie needs: unique setting, high stakes, lovable characters, mystery, twist and turns, and a dramatic ending. The truth is no one really knows about this book. Moby Dick will always reign supreme as the iconic Melville text, but Typee deserves some love, too. It would make a much better movie!

There was one big theme I noticed throughout the book: identity. During his adventures on the island, the main character always walks a fine line between engaging in the native cultural and rejecting it outright. He is afraid of losing his western identity, yet he is forced by his captors to participate in the rituals and ways of the Typee. I used this as a central point of conflict in the script.

One last thing. This script has a lot of what I call “Oh, shit!” moments. You know, when you’re reading a script and something crazy happens and you say “Oh, shit!” out loud. I really worked to put these moments in there because the original text didn’t have enough of them. There’s one particular “Oh, shit!” at the end of Act II that you really shouldn’t miss.

Title: Team Wild Crew

Genre: Action

Logline: A group of loyal, tight-knit MMA fighters, who train by day and rip off drug dealers by night, are charmed by a tough stranger looking to embed himself in their crew.

Why You Should Read: Three goals in mind when I was writing this: 1. I wanted it to be really, really bad ass. 2. I wanted the pace to be relentless. 3. I wanted to write an MMA script because I’m a huge fan of the sport and with Conor McGregor blowing the organization up, some writer is going to capitalize on it. So, why not have it be me? Anyway, The Fast and The Furious is essentially a remake of Point Break, right? Instead of the subculture being surfers we’ve got street racers. I thought I’d do a third reimagining, substituting surfboards and racecars for MMA and FISTS TO THE F*** FACE! Every script I write, I write for whoever’s reading it in mind. Enough of this “slow burn” crap– AIN’T NOBODY GOT TIME FOR THAT! One last thing– I got some coverage from WeScreenplay on this one. The reader ended it with, “easy recommend.”