Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hr. Drama

Premise: Club Lavender follows a transgender cabaret singer forced to go undercover for the FBI to infiltrate a gay private club run by an alleged communist gangster.

Why You Should Read: My script received a recommend on the trackingboard.com in 2016 and yet nobody would touch it because it was too niche. This was when transgenderism was beginning to get mainstream news after Caitlyn Jenner’s recent reveal. Now it’s a year later and I believe it’s the right time for more daring television surrounding controversial matters. Most importantly, my script exists in the new age of television and as such, takes a no hold’s barred approach to the aspects of story realism and grit. So read at your own caution.

Writer: Sylvester Ada

Details: 68 pages

One thing we need more of in Hollywood is unique voices. Most screenwriters tend to come out of that upper middle class white male demographic. The problem is, since most of these people were brought up the same way, they tend to see the world the same way. Not all of them. But most of them. Which is one of the reasons all Hollywood movies look and sound the same.

A couple of weeks ago we had a writer from rural North Dakota, Logan. And you could feel the uniqueness and the truth in his voice when he wrote. He was great at writing about isolation because he grew up isolated. And this week, we have someone who clearly had a different upbringing because nothing you read here feels familiar. This is a unique script and a unique voice. And we’re going to figure out if that translates into a good story.

Sydney Towne is a 20-something female singer at a beat-up old club in 1960s Queens, New York. It’s clear from the way she sings, she’s too talented to work here. But we get the feeling that a multitude of secrets keeps her from singing at the nicer clubs up the street.

After her performance, Sydney gets changed, and that’s when we realize Sydney is actually a man. She heads home for the night, but on the way a few thugs corner her and ask her for a “private” performance in an alley. As they toss Sydney around, debating whether she’s a woman or a man, a man in a mask arrives and puts a bullet in all the thugaroos.

He reveals himself to be James Pompero, the owner of a high class joint uptown called “Club Lavender.” He wants Sydney to work for him, even driving her there and taking her on a tour. That tour reveals a complicated club where gays, transgenders, and straight men with secrets, hide behind masks and enjoy a world they must keep private from their everyday lives.

Sydney wants no part of this but James is nothing if not persistent. Things become complicated when it’s revealed that one of the men James killed was Tiny Pete, the son of Columbo mob boss Carmine Perisco. New York Police Commissioner Arthur O’Reilly comes in and asks Carmine to let them find out who did this. But you get the feeling Carmine’s going to do his own investigation.

The remainder of the script follows several cops, as well as Carmine’s men, as they try and figure out who killed Tiny Pete. Since everyone has something to hide, they’re all trying to reconfigure the variables so that they don’t get exposed. Meanwhile, Sydney’s got to make a decision soon. Or James might nudge all these Sherlock Holmses in her direction. It’s starting to sound like there was never a choice in the first place.

Club Lavender is a really well-written script. Probably one of the best written scripts of the year. But remember, there’s a difference between “well-written” and “well told.” I’m more interested in a well-told story. And I’m on the fence about how I feel with Club Lavender in that regard.

While I figure it out, let’s talk about specificity. Specificity is an advanced screenwriting tool one uses to make their world believable. If you were a beginner screenwriter and you were to describe Club Lavender, you might write, “It’s a throwback to the clubs of the 60s, a beautiful arrangement of old-time elegance, along with some hip trim.” The problem with this description is there’s no specificity. So we don’t believe in the club.

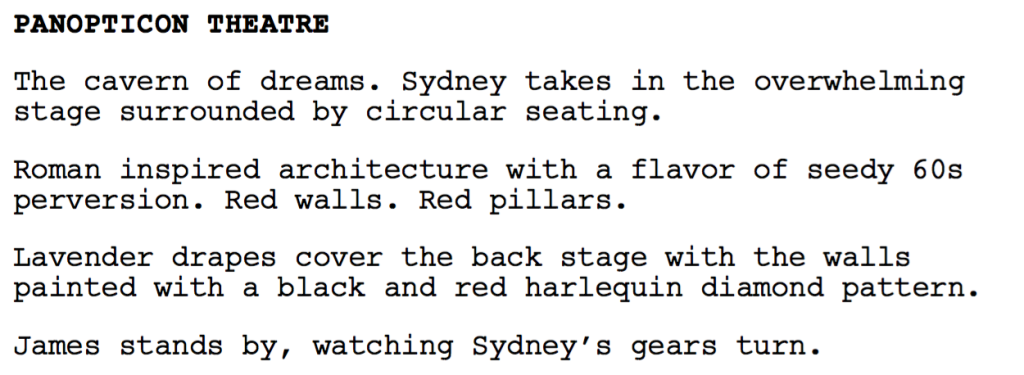

Here’s how Sylvester describes it:

Can you see the specificity there? With that specificity comes our belief in that world. You might be saying, “But Carson, I thought the writing in a screenplay was supposed to be sparse.” It is. Except when you’re describing the important things, the things that matter to the story. This show is titled Club Lavender, so I better get my money’s worth when it comes time to describe the place.

Another thing that Club Lavender reminded me of was that, when writing a pilot, you need “THAT SCENE.” “THAT SCENE” is the scene that shows us why your hero is worthy of watching for 70 hours, AND that’s a good memorable scene in its own right, the scene people are going to be talking about afterwards.

That scene in Club Lavender comes in the form of Tiny Pete and his cronies trapping Sydney in the alley and trying to get her to strip so they can figure out if she’s a man or a woman, and then a masked man shows up and kills them all. That scene had everything – a horrifying situation, suspense, our hero fighting back with everything she had, a mystery person showing up and killing the thugs. It was the moment for me when I truly committed to the script.

But the best thing about Club Lavender is the dialogue.

It’s creative. It’s unique. I’d go so far as to say every dialogue chunk was its own little work of art. And I say that because you can tell Sylvester put everything into every single line. Lesser writers take scenes off. There isn’t a single dialogue scene that was taken off here. It’s all strong.

With all that praise, this script must be getting a genius rating, right Carson? Not so fast. There are a few missteps that kept me from loving Club Lavender.

The first is that the plotting starts to get clumsy towards the end. I was having a particularly hard time following the cops. Writers have to remember that readers lump cops in together. Every time a new cop is introduced, we’re thinking, “Okay, that’s cop number 6 now.” They don’t get that memory bank differentiation that comes from a character having their own unique job.

So when some cops are trying to destroy evidence, others are trying to kidnap Sydney, others are trying to help her, there was another cop I think who was also on the take or something. It becomes easy for us to mix those people up unless we’re taking meticulous notes. And if you’ve got us doing that, you’re making us work too hard. This is why I always say, use as few cops as you can get away with. And for the ones you keep, make sure their names are all really different. And the way they look, act, and talk is all really different. Otherwise, I’m telling you, we’re going to mix them up.

Another thing I had a problem with was this whole communist thing. I didn’t get it. If this script was just about important powerful people – criminals and good guys alike – hiding in this club, I would’ve liked that. But we’re also supposed to believe that these people are communists? Or some of them are communists? Or is this a time when the U.S. was calling gays and transgenders communists even though they weren’t? I didn’t understand it. And since that was the big ending reveal, I was left feeling limp. A pilot is supposed to have you on the edge of your seat ready for episode 2. I was not there after this ending.

It seems to me like that’s a really important story point for Sylvester so I’m not going to tell him he needs to ditch it. But I would. I think it’s unnecessary. You have a club where everyone is hiding something, a Godfather like mob-war subplot, and lots of fascinating characters. What else do you need? If you want to keep the secret agent thing, then have her working for the cops as an informant rather than for the FBI.

With that said, this is definitely worth a read. I’m sometimes asked the question, “How do I know when my writing is at a professional level?” And the only answer I can give them is, “When someone wants to pay you to write.” And I would pay, in a second, for Sylvester to a dialogue pass on one of my scripts.

Think about that guys. If you needed to pay someone to write an idea of yours and it couldn’t be you, whose writing is impressive enough in your eyes, that you would actually pay them money out of your own pocket to write it? Now turn that question back on yourself. Do you believe someone, after reading your script, would pay you to write something for them? If you’re good at being objective, that question can help you understand where you’re at and what you need to work on to get to that paycheck.

Script link: Club Lavender

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Just drop the heater and step away from the lady, before we have one of those closed casket conversations.” Come on, I dare you to write a line as good as that.

It’s the goal of every producer in Hollywood, the dream of everyone who’s ever had an idea for a TV show – to not only create a hit show. No no. Creating a hit show is easy. But to create a WATER COOLER show – the kind of show that’s so good, so exciting, so twisty-and-turny, that people MUST talk about it the next day. Let’s list some of these shows.

But before we do, let me put the needle on the record of some Barry White. Get a good vibe going. Oh yeah, can you hear Barry? I can. Okay, let’s get to that list…

Lost

Breaking Bad

True Detective

Walking Dead

Game of Thrones

This Is Us—

SCRAAAAAAAAAAAAAAATCH

I’m sorry. Run that last show by me again. This is Us??? A show about family with no dragons, no drug dealers, no serial killers, no zombies, and no Others. The show is just about… people? How did a show that ONLY explores interpersonal relationships become so addictive? And what can we learn from it that we can apply to our own TV writing?

Water cooler shows used to be common. That’s because only 30 shows aired a week and even the lowest rated shows did better than the highest rated shows today. Everybody was watching the same stuff so, chances were, you’d want to discuss the latest episode of Seinfeld with your co-worker the next day. Today, with 300+ shows a week to choose from, everybody can pick their own little weird show to watch. And that means writing a show that a lot of people watch and that generates widespread discussion has become almost impossible.

Every network wants the next Game of Thrones but what does that even mean? You can’t just make another swords and sandals dragon show or else it looks like a cheap version of Game of Thrones. The same thing happened when Lost was big. Everyone wanted the next Lost. But you couldn’t replicate Lost. It was too unique.

Enter “This is Us,” the most unlikely water cooler show of them all. And maybe that’s our first lesson of the day. Whenever there’s a mega-hit show, the collective industry response is to try and copy it. But what you’d be better off doing is finding something that’s the opposite, which is what This is Us is.

But that doesn’t explain how this show got so buzzy. Once again, the show relies solely on internal and external character conflict to drive episodes. So how can it possibly compete with a show that spends 25 million on movie-level battles every other other week, or kills off multiple beloved characters in a singular blood-curdling wedding? It seems impossible.

For those who haven’t seen This is Us, go watch the pilot right now. I’m serious. Stop reading this and watch the pilot, because it’s one of the best written episodes of television ever. Also, it’s impossible to talk about the show without indirectly spoiling the pilot. And I need to get into the pilot to explain why this show is so buzzy. Okay, did you watch it? Are you sure? Cause every sentence going forward is a spoiler. You’ve been warned!

For those who don’t have the time, This is Us follows “triplets” Kevin, Kate, and Randall Pearson. Kevin is a handsome successful sitcom actor who decides to quit his show to pursue theater in New York. Kate is his extremely obese manager whose entire life revolves around trying to lose weight. And Randall, who is black and was adopted by the same parents of Kate and Kevin, is an extremely smart and successful businessman with a great family.

The show, however, doesn’t just cover the triplets in the present day. Half of every episode is dedicated to 30 years ago, where we show their parents, Jack and Rebecca Pearson, going through the struggles of being a young couple trying to raise three kids.

There is one more major plotline, which is that Randall seeks out his biological father, William, who left him at a fire station that night that Jack and Rebecca adopted him. Randall learns that William is dying, and extends an invitation to move in with him and his family, where he learns about William’s unique life as a struggling artist/addict.

Okay, now that we’ve got the basics, let’s get to why this show, which, once again, is just about people, is able to compete on the same buzzworthy plane as Game of Thrones. We’ll start with the number one reason, which I’m guessing nobody here picked up on. If you did, kudos to you. Cause it took me awhile to figure it out.

This Is Us’s PAST-PRESENT structure allows it to introduce sexier twists and turns than your average character-based show.

Case in point: The pilot. This is Us hides the fact, with clever directing, that Jack and Rebecca’s storyline – they’re at the hospital about to have triplets – is happening in the past. It also hides the fact that Randall, who’s black, is in any way related to Kevin and Kate. This allows them to throw a quadruple-whopper at us in the pilot’s climax. Jack and Rebecca’s storyline is set in the past, one of their triplets dies during birth, Jack and Rebecca decide to adopt Randall, who was dropped off to the hospital during delivery, which, of course, means that Kevin, Kate, and Randall are all siblings in the present. Wow! Now that’s writing.

However, even after the gig is up on the hidden past storyline, This is Us still uses it to deliver dose after dose of surprises. For example, at the end of the second episode, Randall, Kate, and Kevin’s parents stop by the house. “Grandpa and Grandpa are here!” Randall’s daughters excitedly yell. We open the door to see Rebecca…. but she’s not with Jack. She’s with Jack’s best friend. Cut to black. End of episode. WTF. This is a twist you can only pull off inside of this unique PAST-PRESENT format. And This is Us goes back to that well again and again (mostly to success, but not always).

It’s funny, when I looked up at my list of water cooler shows, I noticed there are two others that use this exact same format – Lost and True Detective. So there’s obviously something writers have discovered that’s like this little miracle worker for twists. Nobody had figured out how to do that for a character-driven show yet, though. So kudos to Dan Fogelman, the creator of This is Us, for doing so.

From there, This is Us utilizes good old fashioned solid-writing to make sure you love it. In television, your primary job in the pilot is to make us either a) fall in love with or b) be intrigued by each and every character. If you can accomplish that, it’s an investment that pays dividends for a loooong time. We’ll endure some bad episodes if you’ve given us characters we love. And This is Us has some bad episodes. But I don’t care. Because I want to see if Kate’s going to prioritize her relationship over her eating issues, if Kevin ends up with the playwright, or how Will, the biological father dying from cancer, is holding up.

This is Us also utilizes a cheap, but effective, tool for keeping its show buzzworthy. It’s not afraid to kill people. Or, when it isn’t killing people, it’s coming damn close to it. When you look at all those buzzworthy shows – Walking Dead, Game of Thrones – they love to kill off characters. And look at the time tested TV genres – cop shows, medical shows – death is basically built into their DNA. This is Us understands that just having a bunch of people lollygagging around, sharing jokes, isn’t enough. There had to be the threat of death hanging over each episode to give the show weight and generate discussion.

In closing, let me offer you some TV writing advice. And this extends to the feature world as well. I have no problem with writers capitalizing on trends. If you’ve got a Game of Thrones like show that takes place in a completely different setting and feels new and fresh, that’s a powerful marketing tool for you when you go out and pitch it. “I’ve got the next Game Of Thrones” does perk up some ears. However, remember that TV producers hear “I’ve got the next Game of Thrones,” all the time. So going in the completely opposite direction, like Dan Fogelman did with This is Us, may be just as lucrative.

It’s a Scriptshadow Bonus Day! We get a cool sci-fi thriller ANNND you get to download the script yourself at the end of the review!

Genre: Sci-Fi Thriller

Premise: An economist who travels into the future to help the United States government chart a safer and more lucrative path, must decide what to do when, on his most recent trip, he finds his wife murdered.

About: Today’s script was purchased by Sony back in 1998. It was supposed to be directed by Andrew Davis, who made one of the best thrillers ever, The Fugitive. But it never got to the starting gate. The screenwriter, Gregory Hansen, has only one produced credit – 1993’s Hearts and Souls. The Travel Agent was written at a time when Hollywood was celebrating the box office juggernauts that were Titanic and Men in Black.

Writer: Gregory Hansen

Details: 123 pages – “First Revision” 05/08/1998 draft

Something occurred to me while reading The Travel Agent. We haven’t had a great time-travel movie in over 25 years, when Terminator 2 came out. And before that it was Back to the Future. There have been none in the interim. And if you even TRY to tell me that Primer or Looper are good movies, I am going to wrap you in steak and feed you to a litter of angry kittens.

It’s a reminder that while time-travel is one of the most tempting sub-genres, it’s also one of the hardest to master. I think everybody tries their hand at it once and when they realize how difficult it is, they’re like, “I’m never doing that again.” But there is one thing you can do to make your time-travel script easier to write. I’m going to get to that soon. But first, let’s discuss The Travel Agent’s plot…

Victor Barrick is a 30-something economist who works for the government. He’s a smart guy, friendly, a little shy. He’s got a stunning wife and a beautiful home. Best of all, his job allows him to help people. You see, Victor is a time-jumper.

The Jericho Program has discovered a worm-hole that can send people exactly six months into the future. This allows agents like Victor to look at things like how the economy’s doing, terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and report back so the U.S. can adjust accordingly.

For example, in one trip, Victor experiences a huge earthquake up in San Francisco that kills hundreds. Once the government had that information, they could clear people out of the buildings where the deaths were going to occur due to “a poison gas warning” or a fire alarm that was “accidentally pulled” a few minutes before the earthquake began.

Everything’s going swimmingly for Victor, until, on his most recent trip, he learns his wife’s been murdered. Just as he’s processing that, two men come after him, trying to kill him. And he’s only barely able to evade them before jumping back to the past (lots of spoilers ahead – so read the script first if you don’t want to be spoiled).

Victor needs to figure out who killed his wife and why they want him dead too. Oh, but Victor, you so don’t want to know. Jericho’s playing dumb in the past, saying that they don’t know what’s going on or why Victor was attacked. But they close down all jumps in the meantime. Victor gets his tech guy and best friend, Murphy, to jump him back immediately. Once in the future, Victor discovers a horrifying reality. The person who’s at the center of this is… him. Or, at least, Future Him. Whoever that may be.

We ping-pong back and forth between the past and future as more and more pieces of puzzle are put in place. Victor eventually learns that his wife has been playing for Team Jericho this whole time. And that they need to get rid of him so they can do more nefarious things in the future. His entire life a lie, Victor must figure out a way to save himself and expose Jericho for what it is. But he’ll have to overcome the entire might of the U.S. Government to do so.

The Travel Agent is a fun script if you judge it the way it should be judged: As a 90s spec. It’s a fun premise. It’s a silly but enjoyable hero-on-the-run exercise. It hits with some plot beats and misses with others. But, in the end, it’s enjoyable. And I’m going to tell you why this script didn’t fall apart whereas so many time-travel scripts do.

To write a good time travel script, you must nail one thing:

The rules of your time travel must be simple.

What do I mean by this? Where time-travel movies go south are when they incorporate too many rules. Time-travel is confusing as it is. So you must limit your rules to as few as possible. I’m telling you. Every rule you add, you unknowingly add a ton more complications.

For example, if I said you could only jump to the future once a year, that’s easy to understand. If I then said, you could only jump to the future once a year, and you could only stay in the future for 30 minutes before you had to come back? That’s still manageable but the viewer has to think a little more. If I said you got to jump to the future once a year, and you could only stay in the future for 30 minutes at a time UNLESS you were wearing the Time Pendant, which would extend your stay for an extra 45 minutes… you can start to see how things might get confusing. And how they’d become extremely confusing if I told you that only senior time agents were allowed to wear the Time Pendant.

Take Looper for example, with its unending set of rules. Why would you send people back in time to get murdered? Why wouldn’t you just murder them and then send them back so there was no chance of, you know, them getting to the past and being able to escape? Which is exactly what happens!

What I liked about The Travel Agent is it just had one rule. You get sent six months into the future. That’s how long the worm-hole is. You come back when you want to come back. I never had to think too hard during this. I could just enjoy the story.

Unfortunately, just because you keep your time travel rules simple, it doesn’t mean you’ve automatically written a good movie. It just means you’ve mitigated potential problems on the time-travel end. You still have to make interesting inspired plot and character choices throughout, and The Travel Agent does so sporadically.

One of my favorite moments was when Murphy needs to send Victor into the future after Jericho has closed down the program. Usually, Jericho sends you into pre-built “vaults” so you don’t end up, you know, arriving in the future with your body half-melded into a car. But they don’t have access to the vaults now.

Murphy tells victor: “Okay, there’s a run down deserted building that hasn’t been touched in years. There’s no reason to think it won’t be there in six months. We’ll send you there.” So he transfers Vic to the building six months from now and, sure enough, it’s still there. Everything’s fine. He dusts himself off like, “What was all the worry about?” Then the camera shifts to show behind him where a giant WRECKING BALL is swinging directly towards him from outside the building. He turns and notices it at the last second, and must run for his life.

I actually wish there were more scenes like this – scenes that were concept-specific. Again, you’re always looking to write scenes that COULD ONLY HAPPEN IN YOUR MOVIE. And this was one of them. But most of The Travel Agent has Victor running around in a, sort of, carbon copy manner to The Fugitive.

I’ve seen The Fugitive. I want The Travel Agent.

They also did a good job with Hannah, the wife. We saw the same plot beat – the wife working for the bad guys – in Total Recall. The difference here was that we really explored the emotional effects of Victor’s marriage and his life being a lie. Victor was truly traumatized. In Total Recall, Arnold Schwarzenegger gets a really confused look on his face and then he’s off to the races, his fake wife a feint memory.

I don’t know if this script has enough “umph” to be produced today. Maybe Jason Statham could get it made. But it’s more likely to be one of these Bruce Willis or Nicholas Cage VOD things. With that said, it’d be one of the better VOD movies they made in a long time. And it’s got a great title to boot.

Script link: The Travel Agent

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Credit to Scott Crawford for reminding me of this. Raymond Chandler used to say that when his stories would get boring, he would have a knock at the door, the hero answers the door… and it’s a man with a gun. This is a cheap but clever way to add a bump of energy to your script. Remember, though, that this tip has variations. The man at the door doesn’t have to be showing the gun. It can be hidden. And you get to decide who knows what about that gun. Maybe the audience knows but our hero doesn’t. Also, that “gun” is symbolic. It could be an angry friend with a bone to pick, an ex with a score to settle, an apartment manager saying that rent’s past due. Be creative when you have your character with a gun show up at the door.

Is The Umbrella Academy the cooler hipper version of Guardians of the Galaxy that we all deserved?

Genre: Superhero

Premise: An oddball superhero family of brothers and sisters who broke up over a decade ago, must come together when their sister becomes involved in a dark musical plan to destroy the world.

About: The under-appreciated Dark Horse Comics is trying to get another major superhero movie made. Dark Horse is no stranger to film adaptations. They’re responsible for 300, Hellboy, and that Jean Claude Van Damme classic, Time Cop. But “The Umbrella Academy” would be a different beast entirely, a 200 million dollar summer popcorn extravaganza. Which is probably why it hasn’t been made yet. The oddball comic, created by My Chemical Romance frontman, Gerard Way, was purchased by Universal, who has been sitting on it for almost a decade, afraid to pull the trigger. This draft was written by Mark Bomback, who wrote the last two Planet of the Apes films everyone loved so much. Edit: Been informed that Netflix is adapting this now. Definitely better for television format, for all the reasons I bring up in the review.

Writer: Mark Bomback (based on the comic by Gerard Way)

Details: 116 pages

A superhero project that no one’s ever heard of?

And Universal, desperately in need of a superhero franchise, has the rights but isn’t actively developing it?

What, pray-tell, is going on here?

I don’t know why Universal is so anti-superhero. They have the rights to a surefire hit movie on their hands (The Hulk) yet refuse to make it. It’s possible they’ve been smelling themselves since that monster 2015. But now that their big monster franchise, Dark Universe, is D.O.A., they may go back to evaluating their library.

But is there room for any more superhero movies? I would say “No” but every time someone has declared the end of the superhero era, they’ve been wrong. Which means that if you can come up with something fresh and cool, something we haven’t quite seen before, you could strike gold. Is The Umbrella Academy that film?

Sir Reginald Hargreeves (a.k.a. “The Monocle,” a.k.a. an alien) is thrust into action when it’s been revealed that all around the world, 43 babies have been mysteriously birthed despite their mothers never having been pregnant. The Monocle knows that these kids are special, somehow, so he tries to snatch up as many of them as possible.

He’s able to adopt seven of them, which include, Spaceboy, the strongest of the group, Kraken, who can hold his breath for three weeks, Rumor, who can make anything happen simply by saying she heard a rumor about it, Seance, a psychic, The Boy, who can travel into the future, The Horror, who sports tentacles, and Vanya. Vanya is the only member of the family without powers. She’s just really good at playing violin.

The Umbrella Academy, as they are known, become insta-famous before insta-famousness was a thing. They’re like a superhero version of The Beatles. The problem is, they all hate each other and they’re constantly getting into fights. So the public gets sick of them and they all eventually break up and go their separate ways.

Ten years later, Vanya gets an audition to be in an orchestra. But the conductor proves to be a creepy little bugger, revealing that he’s created a piece of music that, when played in its entirety, will destroy the world. Vanya is the only musician good enough to play the violin for the piece, and before she can say no, he puts her in a trance, forcing her to play.

Meanwhile, the academy’s father dies, bringing the family back together. When The Boy shows up – still ten years old by the way – he reveals that he’s just spent the last 60 years in the future, farting around. Oh, one more thing, he says. The future is an apocalyptic wasteland. And according to his calculations, the point of destruction happens in TWELVE HOURS.

The superhero family who hates each other now must figure out who’s destroying the world and stop them. When they realize it’s their own sister, they’ll have to make one hell of a tough choice. Kill their own fam or let the world burn.

Oh, and there’s a monkey that talks too. His name is Pogo.

When you have a ton of exposition and world-building in your story, as is the case with The Umbrella Company, you’re going to have to make some cuts somewhere. You’re going to have to sacrifice scenes or characters or backstory SOMEWHERE. Because if you try and include it all, your script is going to drown under the weight of its own ambition.

This is why I promote simplicity so much. Week after week, month after month, year after year, it’s the only piece of screenwriting advice that holds true for every story and every situation. Get down to the bare-bones of your story, figure out what it’s going to be about, and avoid adding shit that doesn’t matter.

The first 20 pages of The Umbrella Academy is one giant montage of exposition setting up this incredibly complex family. I mean you have non-pregnant women having babies. Talking monkeys. You have kids named 00.01, 00.02, 00.03, who then each get new names, who then each get powers, who we then watch grow up, love each other, hate each other, become stars, break up.

Once that sequence is over, we meet all of these characters AGAIN, but this time as adults. So it’s essentially a second set of full introductions. All of that takes up the first 40 pages.

Now here’s the thing. We will care more about these characters if we meet them when they’re young. There’s no question about that. The longer you know a character, the more you know about them, the more you care about them. But this is what I’m talking about. We’re not operating in a screenwriting utopia where the audience will gladly sit around for four hours while we tell our story.

The audience is the exact opposite. They’re easily bored, easily distracted, and don’t have time to waste. So that means EVEN THOUGH it would be better for character development if we met The Umbrella Academy when they were kids, we need to make sacrifices somewhere. And the first sacrifice probably needs to be made with that opening sequence. Start us when these characters are adults and imply their past.

And I say that factoring in multiple variables, such as the fact that we’re covering SEVEN DIFFERENT CHARACTERS here. If this were about ONE superhero, and therefore we’d be able to set his past up in 1/7th the amount of time, I would be okay with starting this movie in the past. But that’s not the case. We have a ton of characters to cover.

Unfortunately, The Umbrella Academy is battling this issue throughout its screenplay. It’s always one part fun, two parts exposition. And writers have to remember that reading needs to be fun. If it’s work, the script isn’t working. And I know when a script is work because I’m taking notes the whole time. That’s what was happening here. Note after note after note.

And it’s too bad, because I think there’s something to this. It’s sort of like X-Men meets Guardians of the Galaxy, but with its own unique voice, with its own unique aesthetic. I love that this is, at its heart, a story about family. I love that there’s an organic wedge that’s been driven between this family, creating conflict that can be milked in basically every dialogue scene between the family members.

And it’s a different kind of conflict than appears in Guardians. In Guardians, the key players didn’t know each other before they teamed up. So the conflict was more surface-level. Here, the conflict is dripping with history. There’s so much subtext to the conversations because of how deep these rifts go.

And props for writers who finally came up with an original villain with an original plan. In all of these superhero movies and scripts I’ve read, I haven’t come across one with a world-ending concerto.

I didn’t love The Umbrella Company, but I think there’s something here that they should keep developing. It reminds me a bit of Internet Explorer. That used to be the best web browser. But then they kept adding shit and adding shit and adding shit until it became bloated beyond function. That allowed for streamlined browsers to come in and steal their market share. That’s what The Umbrella Company needs to do. It needs to streamline.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you have to include exposition on virtually every page of your script, you’re trying to include too much. This can happen to writers who are trying to be loyal to the source material or writers who want to be truthful to the event they’re depicting (a World War 2 battle they’ve researched extensively, for example). But keep in mind that the audience member just wants a good story. They don’t want to have to take notes for two hours to understand what’s going on.

Genre: Comedy/Satire/True Story

Premise: (from Black List) The remarkable true story of an unremarkable church-going accountant who stole $17 million in the biggest fruitcake heist of all time.

About: This is the breakthrough script from Trey Selman, which made last year’s Black List. When asked in an interview at the Austin Film Festival how it all happened, he answered: “For years it was an unremarkable pursuit as I rolled along – finishing script after script – that no one ever read, until I finally wrote something that people wanted to read. Getting your start in screenwriting always reminds me of what Hemingway wrote, “How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Writer: Trey Selman

Details: 107 pages

My reaction to “The Fruitcake” can be boiled down to my reaction of the script’s first sentence. “A massive split lane chugging between the breast augmentations of Dallas and the refried smog of Houston,” is how Selman describes the I-45 highway.

On the surface, I like that line. But when I start thinking about it, I’m not really sure what it means. What’s “refried smog?” Do they cook smog in Houston? It’s a weird analogy. And that confusion would happen a lot during my read.

Then again, “The Fruitcake” is a satire. And satire has always been a genre that confuses me. I feel like it’s smarter than I am. Therefore, even if it’s bad satire, I’m always assuming it’s me who’s the problem, not it. I don’t know. I’m starting to confuse myself here. Lots of confusion in today’s review and we haven’t even got to the plot summary yet.

Sandy and Kay Jenkins live in Corsicana, a rich little town in the famous (infamous?) state of Texas. Corsicana is best known for one thing – it’s the home of Collin Street Bakery, where the majority of the world’s fruitcakes are made.

Over the years, fruitcakes have become somewhat of a joke. Nobody knows anybody who’s actually eaten one of them. Yet they’re one of the most gifted foods of the holiday season, the solid state version of eggnog.

Don’t tell that to Collin Street, though. They pull in 40 million dollars a year on their fruitcakes. Those little nut and dried fruit patties are like gold. Which is why Sandy Jenkins is so damn confused why he’s not reaping any of the benefits of the business. He’s been an accountant at the company for a decade. He’s the ultimate team-player. He’s friendly. Yet he’s always passed over when it comes time for a promotion.

The truth is that Sandy is kind of a weirdo – the guy at work who wants to be your friend a little too badly. And his wife, Kay, isn’t helping matters. She’s practically begging her richer housewife neighbors to be in their book clubs, even though she hates books. She also says awkward stuff like, “Well, I don’t think we should celebrate until you’re pissing in high cotton, Sandy,” which is a sentence that I don’t understand.

Convinced he’s paid his dues, Sandy stops waiting for the American dream, and instead takes it. He writes himself, we’ll just say, a “secret check” from the company. At first he buys a Lexus. Then a 5000 dollar suit. Then a Bentley. Then a Porsche. Pretty soon he’s paying for 100,000 dollar parties every month.

Meanwhile, the company president, Bob McNutt, is trying to figure out why their foolproof business is losing so much money. He starts looking into it, all the while watching Sandy show up in a new car every day with a new suit every day, with a new watch every day. Gosh, he thinks, if Sandy would stop buying all this nonsense and invest his money into the company, they probably wouldn’t be in the red right now.

That’s how clueless Bob is on the matter. But, come on, how long can you really steal 300 grand a month from your company and get away with it? Believe it or not, a lot longer than you think.

If you liked movies such as Jack Black’s “Bernie” or highly celebrated 2010 Black List script, “Butter,” you’ll like “The Fruitcake.” It’s in that vein. But I struggled with it. My biggest issue was that I felt it was all overwritten.

For example, a basic beat where Sandy gets mad at himself while eating is described as such: “He BASHES his hands down. And like a volcano of reheated Tex-Mex, caloric chaos plumes high.” That’s a very over-thought sentence. And the whole script reads like that.

Dialogue such as: “Alright is a saddle on a donkey, Scott. I’m a four point harness in a Ferrari,” and “Arrived? We’re about to drive an eighteen wheeler of nitroglycerin right through the aristocracy of Corsicana!”

The reason I have a problem with this, particularly on the dialogue side, is that our two main characters, Sandy and Kay, never once speak like real people. They speak in over-the-top analogies the whole time. So how can I take them seriously?

It’s my belief that a movie can only work if you care about the characters involved. And in the case of The Fruitcake, we’re clearly spending the entire script making fun of these people. So why would I care about them?

But The Fruitcake has problems that go beyond that. Once Sandy starts stealing, the script keeps hitting the same beat over and over again – which is Sandy buying more and more stuff. That goes on for like 50 pages.

For the most part, a script is divided into eight sequences of 12-15 pages. Whatever “beat” you’re trying to convey, you want to limit it to one of those sequences. Once you move to the next 12-15 page sequence, you want to focus on something new!

That’s not to say that Sandy can’t keep buying shit in the other sequences. But that can’t be the ONLY thing that’s going on in the story for 50 pages. You need other plot beats to come into play.

For example, towards the end of the story, the FBI secretly catches Sandy, but they tell Bob McNutt if they’re going to convict him, Bob needs to catch him in the act of stealing. That’s a new sequence you could build right there – Bob trying to catch Sandy in the act.

Unfortunately, in the current draft, that moment doesn’t come until 10 pages left in the screenplay. So it’s an opportunity missed. But that’s what I mean. You gotta keep introducing fresh plot directions that make the current 15 pages feel different from the previous 15.

With that said, I liked a few things about the script, such as the fact that Sandy was the ultimate fruitcake. That actors love to play parts like this. And The Fruitcake is doing something different. We’ve got all these true stories showing up on The Black List. At least The Fruitcake is being unique in the way it tells its story. It wasn’t for me. But that doesn’t mean it won’t be for you.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Murder or Money. Murder or Money are the easiest way to write low-budget character-driven screenplays that are still marketable (and therefore still have a chance to sell). How does it work? Just make sure, at the core of your premise, is either murder or money. That’s it. In The Fruitcake’s case, it was money. In The Big Short. Money. In Fargo. Murder. In Wind River. Murder. Murder or Money, baby. Two things the world is fascinated with.