I’ve never forgotten the story M. Night told about how he didn’t know until the 5th draft of The Sixth Sense that Bruce Willis’s character was dead. Before that it was just a movie about a kid who saw dead people in paintings or something. It makes you think, what if M. Night would’ve stopped at the 4th draft? The Sixth Sense would’ve been some nothing movie that was in and out of theaters in a week. Or – and this is what today’s article is about – what if he would’ve turned down the idea? Oftentimes when we get an idea that’s so radical it will require changing a large chunk of the script, a script we’ve already worked so long on, we think, “Eh, it’s too much work,” and we don’t put the better idea in.

You guys know I loved The Big Sick. It was one of my top 3 movies of last year. But I was thinking about the movie the other day when I realized, “Oh my God… they did it all wrong.” The more dramatically interesting version of The Big Sick isn’t the girlfriend going into the coma. It’s the boyfriend. Think about it. The movie is about these parents from another culture who don’t want their son to marry an American girl. Wouldn’t it have been way more compelling, then, if it was the girl who would’ve had to spend time with THOSE parents and win them over while her boyfriend was in a coma, rather than Kumail having to win over parents who really didn’t have any problems with him in the first place other than the minor issue that he’d broken up with their daughter?

Now, of course, there are extenuating circumstances. The event that story was based on REALLY HAPPENED. So to flip the script and write it in reverse would’ve meant inventing 90% of the story. Due to the fact that they were drawing from real life, they were able to make the story extremely specific, which is why it was so good. It didn’t feel like anything else out there. So there would’ve been a risk in putting the boyfriend in a coma. But these are the kinds of things that fascinate me about screenwriting. You’re often faced with these options that could upgrade your script from okay to good, or from good to great! And most writers are scared of following these choices because it means more work.

I don’t know if any of you caught the Counterpart premiere the other day. There I was, at the end of the pilot, watching them wrap the first episode up, and there’s this twist in the last scene to hook us for the next episode. Except, it wasn’t that great of a twist. And, if they would’ve worked a little harder, it could’ve been a great twist.

The story takes place with a wimpy JK Simmons working for a corporation he doesn’t understand. Everything is shrouded in secrecy. Then one day, they call him in because there’s a problem. That’s when wimpy JK meets badass JK. Wimpy JK learns that the building he works at is a porthole to another world exactly like his own, where everyone has a doppelgänger. And the reason they need him is because an assassin from the other world has snuck into this one.

A key storyline is Wimpy JK’s wife, who’s in a coma. Wimpy JK is sad to find out that in Badass JK’s world, his wife is dead. Meanwhile, Wimpy JK’s wife’s family wants to turn off the ventilator keeping her alive. They don’t think she’s coming back. And you can tell Wimpy JK is close to giving in. So they write this scene where Badass JK goes to the hospital room and reams out the wife’s asshole brother, telling him that there ain’t no way he’s fucking killing his wife. It’s one of the best scenes in the pilot.

Anyway, after some assassin scenes, we get to the end of the episode. Wimpy JK is back to sitting by his coma wife’s side, being supportive, and we cut to Badass JK heading back to his world. We follow him into a diner, where he sits down, orders a drink, and who should sit down across from him? But his wife! It turns out his wife IS ALIVE. He was lying to Wimpy JK. It’s a kind of cool twist. But was it as good as it could’ve been?

What if, instead of Wimpy JK’s wife’s family failing to end her life, they’d succeeded? And Wimpy JK watches helplessly as his wife is pulled off the ventilator and dies. Think about that for a moment. There is now no wife left, in either this world or the other one. How much cooler is it, then, when we cut back to Badass JK, only to find out that his wife is still alive? Now that’s a twist with some meat on it. Your mind starts to bounce around thinking, oh my god, Wimpy JK still has a chance to be with “his” wife again.

In the pilot’s defense, it is a TV show. So maybe they didn’t explore that twist because they have something better in mind for later. But I have a theory here. And this is where we get into why screenwriters are afraid to follow these game-changing choices. Writers LOVE bullies-get-bullied scenes. And it IS a great moment in Counterpart. The wife’s brother had been bullying Wimpy JK the whole show. So it’s fun to see Badass JK come in and lay into him. These are the scenes writers live for.

But they’re also scenes that can blind you. The writers probably realized that in order to incorporate the scenario where Wimpy JK’s wife was put to death, they would have to get rid of that – the best scene in the script – because that’s the scene that makes the brother back off and stop pursuing his sister’s death. Since everybody loved that scene, they made it a priority over what would have led to a much cooler final twist.

This is one of the tough things about writing that nobody talks about – difficult choices that can improve your script, but at the cost of losing things you like. It’s my opinion that the weaker screenwriter always plays it safe. They like their comfy little story, their cool scenes. And would rather keep them than potentially strive for excellence.

One of the more well-known “What-if” screenwriting breakdowns is NerdWriter’s video essay on Passengers. As those of you who’ve read this site for a long time know, Passengers was considered to be the best unmade screenplay in Hollywood behind Killing on Carnival Row. But the movie was a big fat, “That’s it?” NerdWriter attempted to fix the script by eliminating the opening section where Chris Pratt spends 25 minutes becoming lonely, which leads to him opening Jennifer Lawrence’s sleep-pod, dooming her to the same existence as him.

NerdWriter’s argument was that if you start the movie on Jennifer Lawrence’s character, show her wake up, and follow the movie through her eyes instead of Pratt’s, the movie is creepier. She meets this guy. He seems nice. But is he? You then play the plot out more like a slow-burn horror film. However, what Nerdwriter fails to address is that you need to refill those 25 minutes of the movie you excised. “Is he or isn’t he bad?” in a movie where there are only two characters is a plotline you can play out for, at max, 30 pages, until the reader gets impatient. So what do you fill the rest of the movie with, especially since you now have to find an additional 25 minutes of story to add? Not to mention, the choices changes your entire genre. In other words, every choice that improves your script comes at a cost.

But the beans I’m selling here are that you should never pick a choice because it’s easier. And you should never write off a choice because it means getting rid of a scene or a section or a character you like. If the choice you come up with is better than what you got, and you’re not on some tight deadline, go with the better choice, no matter how long it takes. Because, guys, it’s not hard for anyone in Hollywood to find “okay” scripts. It IS hard to find great scripts. And great scripts require bold choices, even if they mean rearranging everything you thought your screenplay was originally about.

I’m curious to know from you folks. What movies have you seen where you thought, “If they would have made this one simple change, the movie would’ve been so much better!”

Genre: Biopic

Premise: He’s considered by many to be the most popular serial killer of all time. This is his story. Or his version of it.

About: Today’s script landed on the 2012 Black List AS WELL as winning the Nicholl Fellowship that year. Zac Efron is starring. He’ll be joined by suddenly hot again actor John Malkovich, whose been making waves for his gone-viral Patriots playoff game tease. Screenwriter Michael Werwie has been going through that painful waiting – 6 years! – process so many new screenwriters must go through to get to the land of consistent paid work. Well, that time is almost here.

Writer: Michael Werwie

Details: 112 pages

I’m always torn about the Oscars. On the one hand, I love the old fashioned competition of it all. I love movies and artists going up against each other for the big prize. Everyone’s got their horse and their dog, so it’s exciting to simultaneously root for and against the movies you love and hate. There’s entertainment value in that. On the other hand, the awards have become so politicized, both in what the films are about and in who gets pushed, it’s hard to take them seriously anymore.

Not only that, but I find it bizarre that we’re celebrating the best movies of the year, and yet they’re all so… sad. I saw a collage of stills of all the Best Picture nominations, Best Actor, Best Actress, and in all of the pictures, not a single character was smiling. So is the message that a movie that brings joy, that celebrates happiness, cannot be one of the best movies of the year? It’s such a bizarre mindset. The LARGE majority of people who go to the movies do so to escape reality, to be entertained. And the fact that the Academy rarely, if ever, celebrates that really bugs me.

With that said, I recognize that the Oscars are the only way to justify investing in hard-sells. That Jan-Feb-Mar time of year is a virtual marketing campaign for all the nominees. So if you can get on that list, you can make a lot of money, and that incentivizes studios to make/buy stuff other than Iron Man. So I understand that the situation is complicated.

Today we’re tackling a script that will probably be one of the 2019 nominees. With Zac Efron coming off the most resiliant box office hit of the year, The Greatest Showman, this is the movie that’s either going to get him to the A-list or prove that he’s not cut out to be top dog. Does Efron have the chops to embody the most famous serial killer of all time? He certainly looks like a serial killer. Let’s see if the role he’s working with is written well.

Ted Bundy, a handsome young law school student, is chugging around in his car in 1974 when he’s stopped by a cop for blowing a stop sign. Earlier that night, in the area, a young woman was abducted from a shopping mall but managed to escape. The local cops think Bundy might’ve done it. And hence Ted is taken in.

But they don’t have a lot on him. No one else saw him but the girl. So it’s an eye-witness case. Ted is optimistic. He gets his law school buddies to help him out and the next thing you know, they’re putting together an air-tight acquittal.

What Ted doesn’t know is that it was his girlfriend, Liz, who called Ted in. She saw an artist rendering in the paper connected to a separate murder case, and thought it looked like Ted. So when Ted tells Liz with utter sincerity that he had nothing to do with this, a bout of guilt overtakes her. What if she screwed up?

Ted is found guilty of abducting the girl, but manages to escape by jumping out the courthouse window. Gotta love 1970s security. Mustaches, cigarettes, and tough looks. After getting re-caught and escaping again (yes, Ted Bundy escaped from jail twice) Ted heads to Florida where he prepares to start over again. And, what do you know, it just so happens that while he’s there, two girls at a nearby college are killed in their dorm rooms.

The cops move in, looking for the killer, and Ted figures it’s a good time to go on the road again. But he eventually gets caught and is put on trial for the murder of the two women. While this is happening, cases are being re-opened all over the U.S. with similar M.O.’s to the murders of these girls.

Ted is oddly calm about the whole thing. He knows, in his heart of hearts, that he didn’t do anything to these women. So all he has to do is prove that in court. And when his local counsel doesn’t share the same approach, Ted fires them and decides to represent himself! This is what begins the single biggest courtroom circus pre O.J. trial.

Meanwhile, Ted is so steadfast in his innocence, that Liz still wonders if, when she called him in that day, she didn’t start a chain reaction that will ultimately put to death the man she loves, a man who may be innocent. So even though they are no longer together, she heads to the trial to personally confront Ted and find out the truth.

“Extremely Wicked” comes at its serial killer story in the most unique of ways: What if you made a serial killer movie, without any killing? Not only that, but what if we never see even a hint of violence from the script’s subject?

That’s the clever angle Werwie approaches his screenplay from. And while at first I didn’t like it, I gradually warmed up to it when I realized what he was doing. Werwie was putting us back in the 70s, before Bundy was convicted of murder, and showing us exactly what everyone knew at the time. Which wasn’t much. Handsome charming guy. Says he didn’t do it. No slam dunk evidence. It’s saying to the viewer, “You might’ve been duped, too.”

It’s also wonderfully ironic. I mean look at the title: “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile.” Yet we don’t see a SINGLE IMAGE in the movie that represents any of those words. Seriously, if they wanted to, they could rate this movie PG. That’s how much violence shows up in it.

Another benefit of never seeing the murders is that while we don’t sympathize with Bundy, we certainly don’t hate him. Hell, when he jumped out of that courthouse and made a run for it, I was surprised to find myself rooting for him! He didn’t seem like a killer to me. And because the public back then didn’t know what we know now, it’s understandable that people would’ve felt the same way.

Chalk this up as another win for my beat-a-dead-horse advice: Whatever story you choose, find a new angle into it.

That’s not to say the angle was genius. By choosing to avoid the juiciest details of our protagonist’s life, the story lacks any big “wow!” moments, creating a roller coaster ride where all the drops are short and there aren’t any loops. Bundy escaping prison twice was fun. But 60% of this movie is scenes where Bundy is telling people he’s innocent. Those scenes get better as the walls start closing in and he remains defiant. But I’d be lying if I said it didn’t get monotonous.

I’m still unpacking this one. I love the audacity of a writer choosing a subject matter then not giving us anything that comes with it. Here’s where I think the script runs into trouble, though. 90% of this script is Ted Bundy. Which means the whole thing rests on if he’s a compelling character. The problem is the script hides 90% of who Bundy is. We only see the smile. And while there’s definitely something chilling about that, it’s hard to dramatize 2 hours of smiles and denials.

This is a tricky one. But I’d say it’s worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script has me wondering, what if you applied its formula to other genres? What if you made a war script… without any war? A hitman script… without any hits? A superhero movie… without any heroics? My first inclination is that you don’t take away the one thing a subject matter promises. But this script reminded me that the only way to truly write something original is to the think out of the box.

Today’s review includes one of my favorite little-known storytelling devices. So read on to add a new screenwriting weapon to your arsenal!

Genre: Horror

Premise: A young woman with a history of mysterious behavior falls in love with a classmate during her first year at university to devastating results.

About: Take note of this name – Joachim Trier – because I’m laying down money he’ll soon be announced as the director for one of Marvel’s upcoming movies. My guess is it’ll be Black Widow. While the Norwegian filmmaker has been directing movies for over a decade, Thelma is receiving international acclaim, unexpectedly crossing over into all sorts of markets. Trier seems to be enjoying the film’s success with a sense of humor, embracing the “artsy-fartsiness” of Thelma. And so I present to you, the world’s very first lesbian coming-of-age superhero fairy tale.

Writer: Eskil Vogt and Joachim Trier

Details: 116 minutes

Man, this weekend’s box office shows just how difficult it is to survive if you aren’t positioned squarely within one of the big genres. Trying to do something even a little bit different – Den of Thieves and 12 Strong – has resulted in some bloody box office results. It’s also evidence that Hollywood still hasn’t figured out conservative America. 12 Strong was aiming for some of that American Sniper money and got a head shot instead.

Since I wasn’t spending any of my hard-earned money on those options, I decided to take a chance on Thelma, a movie I’d been hearing good things about. And after seeing this clip of the opening scene, I knew I was in. There’s something about those Nordics and their cold creepy perspective on life that I’m ALL FOR. :)

WARNING: SPOILERS FOLLOW

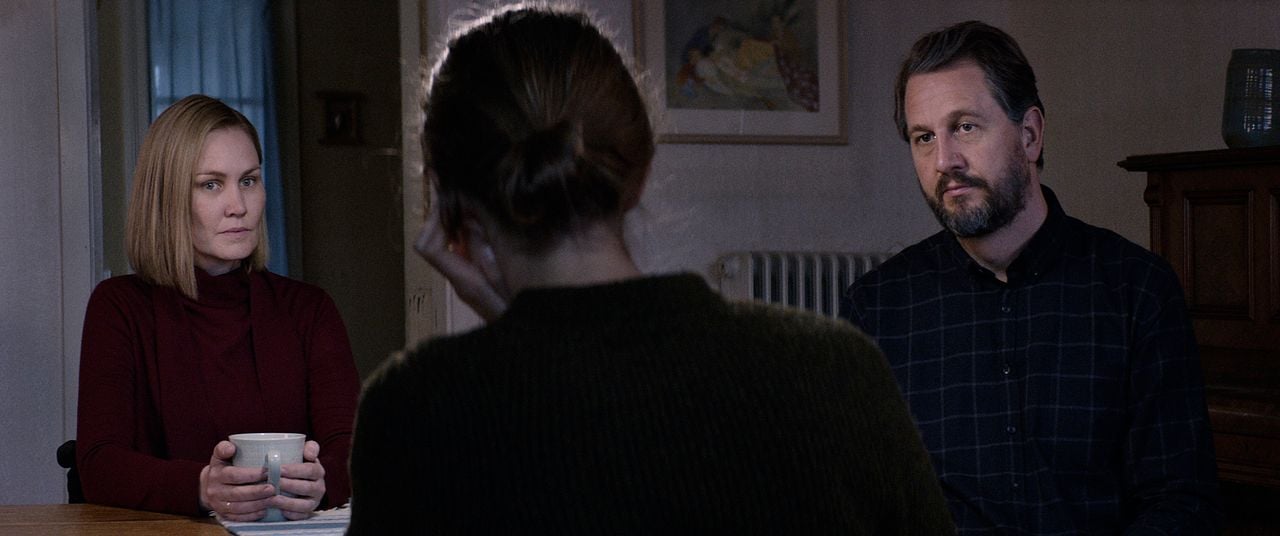

“Thelma” follows the titular character as she goes off to college for her first year. This is a big deal as, up until this point, Thelma’s lived a sheltered life, a life with two extremely religious parents, particularly her father, whose intense calm seems to be hiding an inner rage that could emerge at any moment.

Thelma is ill-equipped to handle the social side of university, so she spends all of her time on her own, until she meets the intriguing androgynous beauty that is Anja. Thelma needs education on even the most basic of social functions, such as friending somebody on Facebook, but once her friendship with Anja ramps up, a whole world of fun follows.

But it turns out all of this social contact is too much for Anja, as she starts having seizures not even doctors can explain. Anja tries to help her through it, and as the two grow closer, Anja takes their friendship into the romantic arena, something Thelma is both drawn to and ashamed of.

She repents as much as possible, asking God for forgiveness, but can’t shake these feelings. It’s around this time, through a series of flashbacks, that we begin to see another side of Thelma, a mysterious dangerous side that hints at the impossible. Thelma, her family fears, has the power to hurt others through thought.

When Thelma and Anja’s relationship goes sexual, Thelma’s had enough, and begs her subconscious to eliminate these feelings. Her subconscious obliges… by erasing Anja from existence. When Thelma goes to their favorite coffee shops, their classes, their hangout spots, Anja is gone. What’s happened to her? Has Thelma really erased her best friend? Or might the answer be tied to her controlling father, who hasn’t told Thelma everything about her childhood?

Place a heavily religious character in a situation where they’re tempted by “sin” and you’re usually going to come up with something good. It gets even better if there’s real danger attached to the sin. This is the secret sauce that drives the middle of Thelma. We’ve set up that the father is a powder keg (the “danger”), then introduced the storyline that could ignite him (the lesbian relationship, the “sin”).

This is a great tip for those of you struggling with seconds acts. Second acts are more about characters dealing with internal and interpersonal conflict than they are pushing the plot forward. So if you establish that your main character must adhere to a certain path, then throw a juicier path in front of them, conflict naturally arises as the character is pulled between the two.

That’s the bulk of what Thelma is. She chooses the sinful path then must battle the conflict within herself to resolve the choice.

There are actually lots of great screenwriting nuggets in Thelma. One of the things Vogt does exceptionally well is build anticipation. Anticipation is one of those things that, if you can master it, you can easily keep a reader glued to your script for 10-15 pages at a time.

For example, in an early conversation between Thelma and Anja, Thelma admits that she tells her father evvveerrrrything. Anja thinks this is a little weird but to Thelma it’s normal. She’s always been close to her parents. In addition to this, we establish how religious Thelma’s father is when Thelma wrestles with whether to tell him she drank a beer. Just the thought of having to admit such a sin brings her to tears.

So when Thelma engages in a lesbian romance: WE KNOW THAT THE TALK WITH HER FATHER IS COMING. This results in… ANTICIPATION. This is a guy who we were afraid of over a beer. We can only imagine what he’s going to say once she admits to having a homosexual relationship. So from the moment the romance commences until Thelma makes that phone call, we’re in anticipatory mode, dreading it.

But let’s get to what I promised you in the header. What’s my favorite unknown storytelling device? Are you ready for this? It’s “Out-of-order flashbacks.” I LOOOOOOVE out-of-order flashbacks! They’re my fave. It’s a wonderful way to fuck with the reader. And Thelma kills it in this area.

We open up the movie with that scene I linked to above. The dad takes 6 year old Thelma hunting. When they see a deer, he raises the gun to shoot it, then, with Thelma standing a bit ahead of him so she can’t see what he’s doing, he slowly points the gun at the head of his daughter. We’re thinking to ourselves – EVVVVILLLL DAD!! I hate this guy!!

However, 30 minutes later after we’re ecstatic that Thelma has finally escaped her father and is at college, we engage in another flashback, also when Thelma is a little girl. Except in this flashback, which takes place before that day, the family has a newborn baby boy. Uh-oh. There ain’t no newborn in the present. What happened to him? As the newborn cries away in its crib, becoming more and more irritating, Thelma closes her eyes, thinks real hard, and the baby is… gone. The parents come in, confused. Where’s the baby? It’s only after looking around that we find him under the couch.

All of a sudden, we’re not so sure the dad is the problem here. Maybe Thelma is the problem and the dad was right to consider killing her. This is why playing with out-of-order flashbacks is so fun. You can change the entire lens from which your audience sees your characters in an instant, forcing them to revisit every scene from a new perspective.

Keep in mind that you don’t have to limit the flashbacks to two. You can continue to use out-of-order flashbacks throughout the script. Maybe, for example, on the third flashback, you switch things around to make it look like Thelma is the good guy again. Then in the fourth, Thelma’s bad again. You can keep the audience guessing all the way til the end.

Even beyond the screenwriting, this is a great movie. The direction is awesome. Lots of wide beautifully composed shots. The acting is incredible. The main girl is amazing. The casting is great. There isn’t a weak link in the film. That dad, man. Whoa. It’s dark. So if you’re not in the mood for that kind of film, don’t watch it. But if you’re up for a great creepy atmospheric movie with shades of It Follows and Let The Right One In, Thelma needs to be your next film.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script reminded me that, when done well, a character with strong religious ties being tempted by “sin” is one of the more compelling inner conflict battles a character can go through.

What I learned (turbo-charged): Take note that you have two options as to how to present sin. You can present sin in the context of what’s objectively wrong. And you can present sin in the context of what’s subjectively wrong. The latter plays better onscreen. For example, if a religious person is tempted by drugs, everyone agrees drugs are bad. So the character dealing with that is a bit on the nose. But if a religious person is tempted by homosexuality, as is the case here, many people don’t see that as a sin, and therefore view the hero as a victim of their own religion. Because of this, they connect with and root for the character more, which was the case with Thelma.

Genre: Gothic Drama

Premise: A psychiatrist becomes involved with a disturbed young woman, but falls foul of those responsible for her condition — a former Nazi doctor and mysterious Reverend Sister.

Why You Should Read: Played against the rainy altitude of the Austrian Tyrol in 1975, FROM THE CONVALESCENCE OF CHRISTIANNE ZELMAN is both love story and Nazi fairy-tale. The role of Christianne is tailor-made for an Oscar-bound actress while the script itself resurrects an all but forgotten genre — one that allowed me to showcase character and dialogue inside a heightened storyworld. Indeed, I tried to write something that owes as much to golden-age melodrama as it does to the likes of Tennessee Williams and Rainer Fassbinder. In short, I’m convinced this script is like nothing else around at the moment!

Writer: Levres de Sang

Details: 99 pages

What I admire about Levres is that he seems to understand he’s pushing a story that’s not the most accessible. He knows this isn’t straight horror and that Blumhouse isn’t about to come knocking on his door after reading it. But my question to Levres would then be, what is the goal here? If you write something that’s far outside a noted genre, what can you expect other than for it to be an interesting experiment? I say this because I think Convalescence has the bones of what could be a movie if it was written as a horror-style thriller. I don’t know if Levres is interested in exploring that route, though.

Let’s get to the plot. And I apologize in advance for the vagueness of some of the story beats as I wasn’t always clear what was going on, something I’ll be talking about in the analysis.

It’s 1975. Austria. Dr. Michael Reinhardt, a married psychiatrist, is being called away to evaluate Christianne Zelman, a young woman of 29 recovering from an illness. Reinhardt, I think, is being given the order to classify Christianne as insane so she can be institutionalized.

So Michael travels to Christianne’s home where her mother, Luise, is taking care of her. Christianne also has a young son, Emil. And every night the family goes through an elaborate routine whereby Luise makes warm milk and has Emil takes it to her mother.

Christianne’s a weirdo. She keeps a dressed-up mannequin next to her bedside and will occasionally take on the personality of another woman. When Michael shows up, Christianne isn’t quiet about the fact that she loves him immediately. Michael, despite knowing his patient is unwell, can’t deny he’s intrigued by her too.

The story seems to center on Christianne recounting her past institutionalization, where she was a patient for a mysterious doctor named Rupert Oberweis. It’s through her recounting of this past that we learn a lot of interesting things, such as the fact that Christianne was born on the exact same day Hitler died. And that she was part of a drug program that got everyone in the institution addicted except for her.

As Christianne falls more in love with Michael, he will have to sort through his own growing feelings to figure out what happened to Christianne in that facility and why it is that everyone seems so nervous by Christianne taking a liking to him.

Let’s start with the writing here because I had a tough time with it. There is a pervasive fuzziness, both in the way characters were introduced and the way plot points were unveiled that often left me unsure of exactly what was going on.

My guess is that this is a component of the genre Levres is shooting for? I noticed Levres and a few others in the comments talking about this as a some form of 70s dream sub-genre? Which would mean the fuzziness is deliberate? Which is cool if that’s the way the genre works. But I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t frustrating to sort through.

I mean we can start right at the title. I didn’t know what “Convalescence” meant. It’s not a word that has come up in any conversation or reading of mine for the past 30 years. And I believe it’s the writer’s job not to assume that any non-basic word is a given. It’d be nice if a character explained what was going on with Christianne without using that word.

I suppose this leads to a deeper line of questioning in regards to the expectations Levres sets for this story, namely, “If you don’t know what convalescence means, you’re not my audience anyway.” And is that approach invoked throughout the screenplay, where it’s kind of like, “If you can’t keep up, sorry not sorry.”

But I had real problems sorting out what was going on because SO MUCH was fuzzy. I’ll give you an example. About midway through the script, the characters find three dead women who were creepily embalmed. I don’t know any situation by which you find three young women dead and embalmed where there aren’t 30 policeman swarming the place within an hour and the media swooping in going crazy. But for the characters in Convalescence it was like, “Whoa, that’s weird,” and they just keep going on like it was no big deal.

That kind of thing would happen a lot where you’d say, “Wait a minute. Why are people acting this way?” Or “Why is this happening?” “Why isn’t that happening?” And I was never entirely sure. At a certain point, around page 70, I lost the will to search for logic. I figured if I couldn’t take anything at face value, what was the point in trying to make sense of things?

Again, I don’t know if this is a specific sub-genre where this kind of thing is encouraged. If it is, then I’m not the audience. But if we’re judging this strictly as a screenplay, I would’ve liked for everything to be clearer. I would’ve liked to know exactly who each character was when they were introduced. When plot points were hit, I would’ve liked for them to be hit hard and clear. For example, another WW2 film, Indiana Jones. Two guys sat Indiana down and said, “This is what you need to do, and this is why you need to do it.” And they went into extreme detail. This may seem like pandering to some. But this is the setup for your entire movie. You want your audience crystal clear on what the hero’s goal is.

I never truly knew what Michael was there for. I think he was there to diagnose Christianne to possibly re-institutionalize her? But I was never clear on why that needed to be done. I also wasn’t clear on what this previous institution Christianne was a part of was. What she was doing there. No character ever explained it satisfactorily (or clearly). And this added to the pervasive fuzziness of, basically, every plot point and character in the story.

I don’t know. It’s frustrating because I like a lot of the elements here. Mysterious woman. A past filled with secrets. Top secret medical experiments. Nazis. Hitler. All of that stuff is right up my alley. I SHOULD be the audience for this. And yet all of those plot points were buried inside of developments I only partially understood.

I would like to see Levres attempt to tell a more traditional horror story with more traditional horror beats. Even this one, but stripped away of all the wishy-washy elements and with all the plot points hit hard.

1) Michael’s bosses are mysteriously strong-arming him: We need you to go classify that this girl is insane, whether she is or not.

2) Meet the girl. She’s weird and intriguing. Something terrible happened to her. Michael wants to know what.

3) There are hints that she may have been involved in Nazi experiments.

4) There are hints that she may even be tied to Hitler himself.

5) The residents of the small town start to strong-arm Michael when Christianne reveals too much.

6) Michael is in danger. He has to get out alive. But he’s resigned to find out the truth first.

What’s wrong with a simple horror story like that? You’ve got the atmospheric writing down. You just need to write more clearly – clarifying characters and motivations and major plot points. There’s a fogginess to the writing and this story that’s obstructing what could be really cool. Then again, maybe that’s not what Levres is interested in.

Script link (updated version): From the Convalescence of Christianne Zelman

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a big misconception out there that you should be writing for yourself. Make yourself happy and you’ll write something great. Of course you should be writing stuff that interests you, but never forget that you’re writing for the reader. You’re writing to give them an entertaining experience. I think Levres was focused more on writing for himself here, and that got in the way of creating something a reader could engage in.

One of the things that separates professional writers from amateurs is character work. Their characters are deeper, more compelling, and overall more memorable. Unfortunately, it’s difficult for the amateur writer to understand WHY their characters lack these qualities. All they hear is, “The characters lacked depth,” or “The characters weren’t three-dimensional.” What the hell does that mean? How do I fix it? Even if you asked the person who gave you the note, they probably wouldn’t know. Creating rich compelling characters is the hardest thing to do in writing.

Luckily, you’re talking to the guy who’s read every script on the planet. And if there’s one thing I’ve discovered, it’s that when a character goes bad, it’s because the writer doesn’t understand the basics of character creation. They may have added a flaw, some inner conflict, a vice, and yet they keep getting the note that the characters don’t work. The writer points to his script: “But look! The proof is right there! I’ve added all the things I’m supposed to add. You’re wrong!” Sorry, just because you have bread, beef, and thousand island in your fridge doesn’t mean you know how to make a Big Mac.

I’m not going to give you ALL the ingredients to creating a great character. There’s too much. An extensive backstory. Approaching the character truthfully. Creating the kind of person who says interesting things and talks in an interesting way (which leads to good dialogue). And yes, strong flaws, some inner conflict, and a well-explored vice help as well. All of that takes years to master. But what I can give you is the base from which to start. If you can get that base right, all of the other stuff will come. How do you find this base? You ask a simple question: What’s their thing?

A character’s “thing” is the component that defines them within the construct of the story. Strip away the bullshit. Get to the core. What is the thing that defines them? Bobby Riggs’ “thing” in Battle of the Sexes is that he can’t handle being out of the spotlight. He’ll do anything to stay in the public eye. Liam Neeson’s “thing” in Taken is that he wants to make up for all the lost time with his daughter and is willing to do anything to get back in her life. Tommy Wiseau’s “thing” in The Disaster Artist is that he just wants a friend.

If you understand that beyond the bullshit, all that confusing flaw/conflict/vice shit, that a character is just looking for a friend, it becomes so much easier to write the screenplay because the majority of the scenes will involve challenging this premise. An example from The Disaster Artist would be when Tommy comes home after a long day and finds Greg in their apartment with his girlfriend, watching a movie. You can see the jealousy dripping off Tommy’s brow, and while he pretends to be okay with everything, there’s a sting to his words, a fear of betrayal. This man’s thing is that he just wants a friend. Here he is potentially about to lose one to this girl. That’s what makes a good movie scene.

If you don’t know your character’s thing, you can’t write a scene like this. I’ll give you an example, and it’s from my least favorite movie of last year, Beatriz at Dinner. The movie was about a poor masseuse/healer who gets stuck at her rich client’s home during an important dinner. The writer tried to get too cute and give the character too much going on. As a result, we had no idea who she was. And the choices that the story made were, predictably, directionless as well. At first Beatriz was a voice for the poor and overlooked. But then they introduced this thing about her loving animals and being upset that animals were being abused (what the fuck???). And then she becomes suicidal, which contradicted everything that had been set up about her. The character was a complete mess and it’s because they tried to do too much. They should’ve asked, “What’s her thing?” and stuck with that thing!

This is a huge problem with screenwriting in general is that writers think they have to get too complex. The solution is almost ALWAYS to simplify, not complexify.

To help you further understand this tool, here are 15 characters and their “thing.” A couple of points I want you to notice. First, take note of how SIMPLE they are. And second, remember how the majority of the scenes in the movie put that thing to the test. So with Mikey in Swingers, every scene either mentions Mikey’s ex or, if it doesn’t, deals with it indirectly. Mikey losing at blackjack is only made worse by the fact that he has no one to emotionally support him anymore. Okay, let’s take a look…

Peter Parker – Wants to save the world despite the fact that he’s not ready.

Mikey (Swingers) – He can’t get over his ex-girlfriend.

Jordan Belforte (The Wolf of Wall Street) – Craves excess. Always wants more.

Deadpool – Wants revenge.

Rick Blaine (Casablanca) – Doesn’t stick his neck out for nobody.

Luke Skywalker (Star Wars) – He dreams of making a difference and going off to do bigger better things.

Ferris Bueller – Just wants to have fun now, embrace the moment.

Furiosa (Fury Road) – Get these women to safety.

Harry (When Harry Met Sally) – Doesn’t believe men and women can be friends.

Officer Hopps (Zootopia) – Prove that anybody can do anything if they put their mind to it.

Mila Kunis (Bad Moms) – Sick of being perfect.

Robert Pattinson (Good time) – Will do anything for his brother.

Anne Hathaway (Colossal) – Can’t get her shit together.

Matt Damon (The Martian) – Methodically solve each and every problem one at a time.

Tommy (Dunkirk) – Survive by any means possible.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!