Genre: Sci-Fi Drama?

Premise: (from Black List) An exploration of relationships as a man witnesses different types of love across the ages.

About: This one finished pretty high on last year’s Black List. This is Tom Dean’s breakthrough script.

Writer: Tom Dean

Details: 127 pages

I didn’t make it to Baby Driver this weekend. Maybe I’ll see it tomorrow and do that script-to-screen review for Wednesday. The movie’s doing quite well, which, despite my negative script review, I’m happy about. We need more filmmakers taking chances like Wright.

Speaking of a movie that didn’t take ANY chances, The House was decimated at the box office this weekend. I’m not surprised. It always felt like a lazy idea. Plus, marriage isn’t funny. If you look at the history of comedies, marriage has never been funny.

Then there’s the new Netflix show, GLOW. I don’t know what to make of that one. I’ve watched four episodes and the writing vacillates between really good and really sloppy. The majority of the scenes feel like they were filmed before anyone knew the cameras were rolling. And the main character, played by Alison Brie (the whole reason I tuned in), is inexplicably kept in the background the majority of the time. I haven’t given up on it yet. But episode 5 better be awesome.

Moving on to today’s script, I’m surprised I haven’t reviewed it yet. It’s on the Black List. It’s time-travel. Sounds right up my alley!

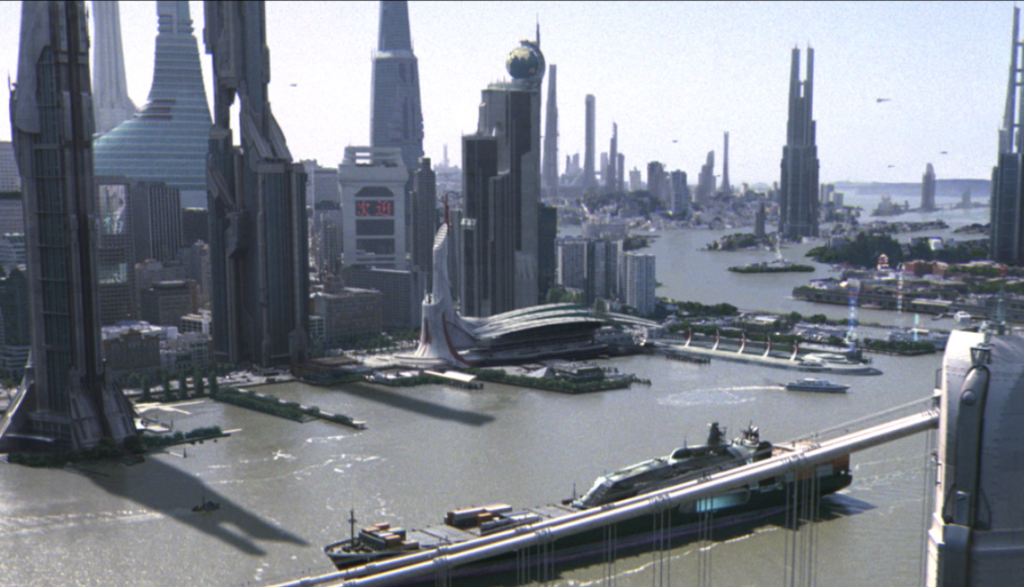

The year is 1960. Sort of. This is 1960 after the invention of time-travel. Which means there’s been some changes. Subtle changes. Like futuristic shit stitched in. But changes nonetheless. It’s here where our Narrator, who will take us through the many time periods in the story, introduces himself. He explains that it’s his job to keep lovers properly meeting each other in all the various time periods.

We first get to know Cecile and Sanjay, who live in Napa Valley circa 1820. But, once again, you have to remember that just because we’re in 1820, doesn’t mean that the characters were born in this era. Both Cecile and Sanjay are from different time periods in the future, or at least, some future after 1820. We watch both of them get in a huge fight, and then we cut to New York City, circa 2402.

It’s here where Sanjay is now a young assistant at a giant company. He’s told by his boss, Henri, to deliver a gift to Henri’s wife back at their condo. Once there, however, a 50 year-old Claire, Henri’s wife, discusses happiness and love with Sanjay before ultimately seducing him.

From there, we cut to Nice, France, circa 1930, where we meet Claire as a 25 year-old. She’s just moved here, and a young cop named Antoine knocks on her door to see if she knows anything about a murder that was committed outside. Antoine falls in love with Claire at first sight, but must use his fellow English-speaking cop to translate his love for Claire.

Cut to 40 years earlier, also in Nice, France, where Antoine is now older, or maybe younger, and is now an actor. Antoine is now in love with Roland, a 30 year-old transgender man. The two fight with each other about their future, specifically how Antoine cannot be with a transgender person.

That takes us to about page 70. And I could go on. But I think you get the idea.

The original paragraph that I was going to write here, I deleted. It was too personal, too negative. And I think Dean deserves credit for his ambition. Without ambition, we get Transformers 6. There’s something to be said for artists who stand up to movies like that.

However, I can’t get past how unnecessarily complicated this story is. There’s the time-travel mythology. There’s a complex narrative. There are tons of rules. There’s no true main character. Dialogue scenes go on forever. The fourth wall is broken. It’s over 120 pages. The characters we do get are all over the place.

For example, one character is a transgender man in one time period, and then a woman when we cut to earlier in his life. Except that he’s actually living in a later time period when he’s younger. It’s almost like the writing is done to specifically confuse us rather than entertain us.

At one point, in 1960, when our characters are going to a movie, they see this on the marquee: “George Clooney in ‘11th Avenue’ Directed by Howard Hawks. His first film after time travel.”

There are also a lot of lines like this: “If it happens you’re familiar with 1820’s Napa Valley, this version won’t look familiar at all. The architecture is limited to the style and technology of early 19th century, but it is very much lived in, developed, and flourishing.”

And then we get dialogue like this: “Okay. Well, when we travel through time, we regulate exactly what dimension it is we travel inside of. That’s why when you travel from 2500 to 1500, you don’t alter the past and create a paradox that would essentially change the course of events so that your parents would never meet and thus never have you and thus never afford you the opportunity to change the past in the first place.”

When you’re reading stuff like this while attempting to follow characters backwards through time, those characters sometimes getting older despite the year being before or getting younger despite the year being after, it gets to a point where you throw up your hands. You’re rooting for scripts that take chances. But if we’re not even sure what’s going on, how can you root?

To the screenplay’s credit, it starts to come together in the end. There was a moment where I thought, “Wow, this reminds me a lot of when I first read Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” But whereas it was always clear in that screenplay what was going on, this one you’re in the dark the majority of the time.

The thing is, there’s a good idea in here somewhere – this concept of following love stories backwards in time. Going in reverse from each relationship to the characters’ previous relationships, and taking that further and further back until you get to the first person who started the chain. But instead we have this time travel stuff which you need Neil Degrasse Tyson next to you to explain.

So what’s the lesson here? I’m not sure. Shouldn’t new writers be taking chances like this? Isn’t ignorance, in a way, an advantage? Christopher McQuarrie stated that his best script, the one that got him an Oscar, The Usual Suspects, was written with barely any screenwriting knowledge. He said that he wouldn’t have done a lot of the inventive stuff he did had he known then what he knows now.

So why beat Dean up for that? This comes back to one of my weaknesses as an analyst, which is my defiance of experimentation. But I think my issue here is a valid one. Had their been one experimental choice, I would’ve been okay. My problem with La Ronde is that there were half-a-dozen experimental choices stacked on top of each other. And screenplays just aren’t built for that. You can get away with it in novels. Cloud Atlas comes to mind. But screenplays are limited in the types of stories you can tell with them. That’s why this didn’t work for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to write long scenes, make sure there’s enough tension to sustain them. If there isn’t, we won’t have enough patience to follow the scene through. So there’s a scene in La Ronde where Sanjay brings a gift to his boss’s wife, Claire. He is supposed to slip the gift in the condo and then leave. It is imperative he not get caught. But the extremely lonely Claire catches him, then asks him to have a drink with her. And they start talking. And then there’s more talking. And then there’s more talking. The talking goes on for a really long time. And because of all that talking that’s going nowhere, the scene loses steam. If you’re going to write long dialogue scenes like this, you need to look for ways to keep the tension. For example, what we could’ve done is had Sanjay’s boss tell him he had to be back within 30 minutes, which is barely enough time to complete the task. Then, when Claire catches him, she tells him, “Don’t worry, I won’t tell on you. If you have a drink with me.” Now Sanjay’s stuck between a rock and a hard place. He has to get back to his boss ASAP. And he has to somehow get Claire to let him leave without ratting on him. Without tension, long dialogue scenes die a sad pitiful death. If you watch any of the master’s long dialogue scenes (Tarantino) you’ll see that all of the best ones are laced with tension. And the few that aren’t, are tension-less.

No review today but not to worry. Any second now, you should be receiving a hot-off-the-presses Scriptshadow Newsletter in your Inbox! Today’s newsletter includes a script review of that spec that fooled Hollywood, some advice on what you should be writing, trivia for half-off a Scriptshadow Consultation and, oh yeah, an UPDATE ON THE SHORT SCRIPT CONTEST.

If you’re on my mailing list and didn’t receive the newsletter, make sure to check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders. It should be in there. If you don’t see it there, feel free to e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “NEWSLETTER” and I’ll send it to you. If you’re not on my mailing list and want on, do the same. Send “NEWSLETTER” to the above e-mail. Enjoy the newsletter, guys. And enjoy the weekend!

A few weeks ago in Amateur Offerings, a Scriptshadow reader brought up that one of the entrants had such a clunky writing style, it was difficult to understand even his most basic sentences. While this is something that happens a lot at the beginner level, you’d be surprised how often I encounter this problem from writers 4, 5, 6 years into their journey.

It’s my belief that these mistakes are made because the writer isn’t aware that their writing is clunky. Usually it’s because that writer isn’t getting enough feedback. But even for the writers putting their work up here, it’s embarassing to tell someone that their writing is at an eighth grade level. It’s easier to focus on some other problem they need to fix. The writer, then, blissfully unaware, continues to write ugly clunky difficult-to-read screenplays.

So today I want to go over the formula for writing a smooth easy-to-read script. Now it’s important to note that the foundation for good writing comes from education. I’m not going to teach you what a noun or a verb is. But even if you aced your AP English class, you still want to keep this formula in mind. Here it is…

Simplicity + Clarity + Voice + Skill = Readability

Let’s go over each of these in detail.

SIMPLICITY

This is the basis for all easy-to-read writing. Keep your sentences simple. The way to do this is to start with a baseline. Whatever you’re trying to say, say it as simply as possible. Don’t phrase your sentence in a weird way. Don’t add a bunch of unnecessary gunk. Give us the action as if you were explaining it to a 3rd grader. So if you want to say that John Wick shoots and kills Frank, write out the most basic version of that sentence as it relates to the scene.

John grabs his gun off the counter and shoots Frank in the head.

This might not be the final sentence you go with. It may need more meat, more punch, more flash. But we’ll get to that. The idea here is to convey what’s happening to the reader as simply as possible. What you don’t want is something like this…

John grabs the jet black gun with authority, piercing Frank between the eyes with a bullet out of hell, who’s dead before he even knows what hit him.

This sentence is technically correct but there’s too much information and it’s a bit of an awkward read. The more words you’re adding, the more commas you’re adding, the more actions you’re adding, the more complex you’re making your sentence. If you keep things simple, you don’t have to worry about clunky sentences. If you want to read a script that embodies this approach, check out Vivien Hasn’t Been Herself Lately, which someone in the comments section should be able to point you towards.

CLARITY

If your writing isn’t clear, forget about us liking your script. We won’t even like your first page. Lack of clarity boils down to three things: poor word choice, awkward phrasing, and the absence of information. The objective of a sentence is to convey to the reader what’s happening. If you’re violating any of these rules, you’re not clearly stating what’s happening. So let’s go back to John shooting Frank. In this version, John’s gun will be in his belt.

John gesticulates his leg to get his gun loose…

This is a classic example of poor word choice. “Gesticulates.” Hmmm… I guess that kind of works? But is it really the best verb to use in this situation? As is the case with all of these examples, I can handle one or two mistakes like this. The issue with clunky writing is that it’s never a couple mistakes. It’s an entire script filled with them.

John gesticulates his leg to get his gun loose and pummels Frank with a bullet.

Here’s where we get to poor phrasing. “…pummels Frank with a bullet.” Once again, I suppose this technically makes sense. But since the average person associates “pummeling” with something other than shooting a man, it forces the reader to stop, reread the sentence, and confirm the action, which is a flow killer. You never want anyone having to reread anything you’ve written. It should be clear the first time around.

Finally, let’s talk about absence of information. This is a HUGE one because many writers (especially beginners) assume that they’re conveying more information than they are. By leaving out the slightest detail or action, a clear sentence can become confusing, or worse, confounding. Let’s say you’re writing a car chase – one of the most famous ever – the semi truck vs. motorbike scene in Terminator 2. Imagine reading a paragraph like this one…

Terminator and John look back at the semi-truck, closing in quickly. He lifts up the shotgun, aiming it squarely at the T-1000 and – BANG! – shoots!

Since you’ve all seen the movie, you know who lifts the shotgun. But imagine if this were at the script stage. A reader would see “He lifts up the shotgun,” and ask, “Who lifts up the shotgun? You’ve listed two people. It could be either one of them.” This mistake is due to absence of information and it happens ALL THE TIME. Make sure you’re reading each of your sentences from the reader’s point of view. Have you included every piece of information necessary to understand the action?

You’re probably saying, “Eh, Carson. Now you’re being picky.” Trust me. I’m not. Cause it’s never just one. Imagine a mistake like this on every page. Coupled with more misused words and more awkward phrasing. A promising script can turn into a 6:30pm drive home on the 405.

VOICE

Voice is the creative side of writing. And, in a way, it works at odds with with our last two elements. That’s because you can’t add creativity without compromising simplicity and clarity. So when it comes to voice, I want you to remember this rule: If it doesn’t make the read more enjoyable, don’t include it. Because that’s the point of voice – to take the words on the page and elevate them to a point where they’re more enjoyable to read.

So what is voice? Voice is the writer’s unique point of view conveyed via a clever phrase, the perfect description, a brilliant metaphor, mastery of vocabulary, an unexpected observation, an important detail, a funny analogy, and the overall style in which they write. Voice does not need to be flashy. It can be subtle. It can be casual. But to make it work, you must be comfortable with your voice. It has to be a natural extension of you. If you force it, the writing will reflect that, not unlike how a nerd looks when he tries to act cool.

Also – and I hope this is obvious – voice should never overwhelm the writing. Content should always be king. Voice is there to supplement the action, not supplant it. A lot of beginners will make this mistake. Let’s go to the master of voice for our next example. This is from Tarantino’s Hateful Eight…

Domergue, whose modus operandi is outrageous behavior and the disarming effect it has on opponents, can’t believe Marquis did what he did. She SCREAMS AT HIM…

When you look at this sentence, you see that it could’ve easily been: “Domergue can’t believe Marquis did what he did. She SCREAMS AT HIM.” But Tarantino loves to tell us about his characters. He loves to add detail wherever he can. So he gave us this minor segue about Domergue before getting back to business. If you were looking to add voice to our now infamous battle between John and Frank, it might read something like this…

John rips his gun off the counter and—

BANG!

Sends a round right between Frank’s eyes, so clean it takes a full three seconds for the blood to flow.

Not going to win an Oscar. But you can see it’s more creative than our original line: “John grabs his gun off the counter and shoots Frank in the head.” Also, note that there’s no end to voice. You can keep going if you want.

John rips his glock off the cheap laminate countertop and—

BANG!

Sends a round express delivery right between Frank’s digits, so clean the blood’s still trying to find its way out.

It’s up to you to decide how far you want to go. If you’re unsure how much is too much, I implore you to err on the side of Rule 1: Simplicity.

SKILL

This is where most writing falls apart. And no, I don’t mean you have to meet a certain skill level to write a good screenplay. But you must know your limitations. The cringiest scripts to read are the ones where the writer is at a level 5 and they’re attempting to write at level 10. Imagine a high school kid trying to write like Cormac McCarthy and you get the idea.

Here’s the good news. You don’t need to be a great writer to tell a great story. But you can ruin a great story by trying to be a great writer. If you’re not a wordsmith, if writing is difficult for you, if sentences read janky whenever you try and get fancy, stick with the first two principles of this formula: Simplicity and Clarity. Remember that the story is the star. If the story is good, you don’t need to dress up the writing too much. I just opened up Terminator 2 and it’s very basic writing. Cameron occasionally gets descriptive but, for the most part, he sticks to simplicity and clarity. So if you can pull those off, and your story’s awesome, you can write a great script.

It’s an early 4th of July review with a special ‘What I Learned’ section that discusses a new screenwriting term you’ll want to wrap a blanket around and take to your next sleepover. Enjoy!

Genre: Historical/True Story/Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) The truly astonishing tale of Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi – the French sculptor wholly responsible for designing, building, and delivering the Statue of Liberty across the Atlantic to where it stands today.

About: This script finished on the lower half of last year’s Black List. It’s written by Jayson Rothwell, who penned 2012’s remake of “Silent Night.” Rothwell’s script must’ve caught France’s attention, as he is now adapting a script for French Based Studiocanal, Ken Follet’s “Code to Zero.”

Writer: Jayson Rothwell

Details: 110 pages

It’s funny.

I tell writers on this site all the time that if you want to break in these days, write a true story. And yet, true stories are the scripts I’m the least excited to read. I only give that advice because that’s what’s selling. And I want you guys to sell!

What’s ironic is that I’ll ultimately have to bare the brunt of this advice when I review the scripts I begrudgingly implored writers to write, lessening the chance that I’ll get a slick new sci-fi spec like “Ex Machina” or an out-of-the-box horror thriller like, “Get Out.” Unfortunately, horror and sci-fi spec sales are harder to find these days than creative freedom on a Star Wars set.

But Liberty has me more curious than most. I’m not going to go all nationalist ‘Merica on you. The only flag waving I do is when I’m flagging down a cab to take me to In and Out. But I’ve always seen the Statue of Liberty as a curious oddity. Why is the thing most associated with our country not even created by our country? Isn’t that weird?

What’s awesome is that Jayson Rothwell feels the same way, and has taken what would’ve been an otherwise stodgy factually-based snore-fest and turned it into a really funny take on the fake news version of Lady Liberty.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, an artist in the year 1871, isn’t the brightest LED fidget spinner on amazon.com. But the man’s got moxie. When Germany attacks the village Frederic is living in, he puts together a small army to fight back. An army of one. Himself.

He charges towards the heavily armored German battalion and is immediately killed via canon fire. Yet somehow, miraculously, Frederic gets back up and keeps charging. This moment is a precursor to a common thread with Frederic, which is that every time you count him out, he gets back up and keeps going.

Now only if he could do it more gracefully. Frederic is a putz. He drinks, he chases women, he bums a couch off his much more successful brother. The only thing Frederic has going for him is his slightly better-than-average artistic skills. The man can build you a hell of a somewhat interesting statue.

But Frederic is tired of building likenesses of local government figures. He’s thinking bigger. So when the opportunity arises for local artists to submit a present to the Americans they hope will solidify relations with their country, Frederic comes up with the most daring idea of all – a giant female statue that represents hope. We’re talking 30 feet tall!

Everyone thinks this is a dumb idea, but Frederic doesn’t care, and begins soliciting every rich Frenchman and American he can find. JP Morgan, Victor Hugo, William Astor. If you had cash, Frederic was at your door. Now America being the destination, the feedback was always the same. “What if we made it… bigger?”

Somehow Frederic scrapes together enough money to start production, and manages to actually build the thing. But now begins the impossible task of getting the statue to America, a feat far from guaranteed. And even if he manages to pull that off, Frederic will face his biggest obstacle yet – a country unprepared to receive the statue since they never believed he would pull it off in the first place.

I was so relieved when I opened up Liberty and read the Narrator’s first passage: “The year is 1870. Here we are in the sleepy French border village of Colmar, famous for absolutely nothing. Not even a cheese. France has declared War on Germany over some bullshit or other. Nobody really remembers.”

I was like, “YESSSSSS!!!!” Finally, someone who doesn’t take history so seriously, who wants to have fun with an idea instead of show us how good their Wikipedia reading skills are.

And I loved the opening scene, with Frederic charging towards the German army all by himself. Getting killed. Flashing back to his past, the goofball narrator making fun of him along the way, then coming back to the future to find out Frederic is still alive. And then the only reason the Germans don’t kill him is because he offers them his mother’s irresistible madelines.

But this is where the script gets itself in trouble. It sets up the expectation of a goofy take on history, yet it struggles to meet that expectation, vacillating between goofball humor (mooning the irritable Victor Hugo when he wouldn’t donate a dime) and an emotional narrative, with Frederic pushing through ten years of adversity to achieve his dream. In fact, by the end of the script, it wasn’t really a comedy at all.

I’ve seen this before. When you come into these scripts guns blazing, you have to have the conviction to follow through. If you move back towards that safe middle, you’ll never achieve that killer crazy script you set out to write. I may not have liked Baby Driver. But that’s an example of a writer who stayed true to his convictions.

Now does that mean Liberty was bad? No. It’s actually quite good. You quickly fall in love with Frederic, who’s the perfect mascot for artists everywhere. I loved this theme that all artists are idiot dreamers until they aren’t – until they achieve that one success.

And that, most of the time, what separates the great artists from the failures is simply the fact that they hang in there. Despite all the ridicule. Despite the family disappointment. Despite living hand to mouth. If you stick in there long enough so that your knowledge catches up to your talent? Success is waiting. How could you not cheer for a character like that? And isn’t that the secret ingredient to any good screenplay? Make us love your protagonist and we’ll forgive your warts.

With that said, I would’ve loved more variety to the plot. Liberty gets stuck on this raising money thing and it milks it for every franc it’s worth. It feels like 50-60 pages of this script are dedicated to raising money. Raising money in France. Raising money in America. Go back to raise money in France. Raise some more money in America. Frederic is always trying to get more money to fund the latest phase of his statue.

Now, on the surface, this meets good plotting criteria. If your hero is always pursuing money, he’s always pursuing a goal, which means he’s active, which means the story is moving forward. That’s exactly what I tell you guys to do. But, you see, you have to add variety to your plotting or the reader gets bored, regardless of whether you have a solid goal in place.

For example, maybe the statue can only be made with a certain kind of copper. So Frederic has to go off and find that copper. That’s not the best idea, but you get what I’m saying. At least you’re MIXING IT UP. If you’re hitting up character number 30 for money, you might be exploiting that plot point a little too hard.

Despite its tonal imbalance and lack of variety, I was so thankful that a script like this wasn’t afraid to subvert expectations. I’m soooooo sick of these true stories that people are only writing cause they’re selling. And while I’d still recommend you do this if you want to sell a script, I’ll also say that readers LOVE when you surprise them, when you do something unexpected. And that’s exactly what Liberty did.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Mini-subplots! Mini-subplots are just like they sound. They’re not full on subplots that take up 12-20 pages of a screenplay (trying to find money for a mortgage payment, for example). They’re cute mini versions of subplots that take up 2-5 pages tops. An example of a mini-subplot is Frederic’s pursuit to get a donation out of Victor Hugo (writer of The Hunchback of Notre Dame). Every 15 pages or so, Victor will tell Frederic to stop bothering him, or Frederic will attempt to change Victor’s mind, or Victor and his assistant will moon Hugo from their apartment across the street. In the end, when the statue is temporarily erected on the Seine River, Victor admits to Frederic that it is a thing of beauty, and has finally reminded him of what happiness feels like. All these little Victor snippets last a quarter of a page, a page at most, adding up to a total of 4 or 5 pages. These mini-subplots don’t define your story, but they add texture to it, and sometimes, as was the case here, lead to some of the script’s most memorable moments.

Unpopular Opinion Alert: The following opinion does not match up with the masses. For that reason, it will likely make you upset. Continue reading at your own risk.

Genre: Dramatic Thriller

Premise: A young getaway driver with a unique condition tries to balance the unraveling of his traumatic past with the increasing pressures of his getaway job.

About: When Edgar Wright was famously fired from Ant-Man after developing the film for 10 years, he wanted to leave the U.S. forever. Media Rights Capital called him right away, however, and said, “Wait a minute. We’ll make any movie you want to make.” And Edgar Wright said, “Baby Driver.” Wright is popular in cinephilactic circles for directing such films as Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Baby Driver comes out tomorrow.

Writer: Edgar Wright

Details: 121 pages

While watching the marketing for the the new film, Baby Driver, a project nerds have been following closely since the infamous Ant-Man debacle, a couple of phrases kept dancing through my head. “Over-directed.” “Wants really bad to be the next cool thing.”

I’ve always been a believer that you make the best movie you can and let the chips fall where they may. When you try to become the hot cool thing before you’re the hot cool thing, you risk coming off as try-hard. That’s what Baby Driver looked like to me. The embodiment of try-hard.

With that said, Edgar Wright’s at least trying something different. And since there aren’t many directors who get that chance these days, it’s nice when one’s given the opportunity. This ensures that not everything is The Mummy’s Transformer Pirate Number 9.

And this one’s got a unique hook. The entire movie is constructed to its soundtrack, in rhythm. It’s for that reason why I wanted to read the script so badly. These music-centric movies struggle to come alive on the page. So, I thought, if Wright could somehow pull off a musical movie in screenplay form, he really would be a genius. That was the hope I had going into Baby Driver.

Baby is a getaway driver. That’s right. The main character’s name is Baby. We’ll get back to that. As for right now, we discover that Baby got into a bad car accident when he was seven. He’s since had to deal with a terrible ringing in his ear. The only thing to keep that ringing at bay is music. Which is why Baby goes through his entire day, including his getaway drives, listening to music.

Baby’s crew includes Doc, his boss, Buddy, a 40 year old who parties too hard, Bats, a crazy motherfucker who loves raising hell, and Darling, a former stripper whose biggest talent is making out with Buddy. Nobody understands why Baby is such a weirdo. But he’s such a great getaway driver, they don’t care.

After a few successful robberies, Bats goes batty and guns down a couple of thugs during a high-stakes deal. This forces Baby and the crew to escape a much nastier type of threat. They succeed, but Baby is rattled for the first time in his life, and his emotions are pulled even further out of whack when he meets a beautiful waitress at the diner his mom used to work at, Deborah.

Baby’s carefully controlled symphony is falling apart. And as we learn more about his volatile childhood, we realize Baby is still stuck in that 7 year old kid’s mind. He will need to get out of it if he ever plans to truly grow up. But should that happen, he will have to leave behind the only thing he’s ever been good at. Can Baby finally stop pressing play?

Hmmm… I know Edgar is loved by many.

But man does this feel try-hard. This is the most manufactured backstory in order to create a specific condition that I’ve ever read. This violates one of my primary rules of great writing. It reads like it was written. You can feel every word being typed as you read the script.

To be fair, the more stylized stuff tends to feel more written. But Tarantino’s able to pull it off. He gets super-stylized and keeps his dialogue and choices invisible.

But it’s the little things here that bothered me. In order to be extra hip, Baby doesn’t use a current iphone for his tunes. He uses a classic ipod! Or, after a getaway sequence, the description reads: “That was something,” or “The syncopation of music and action is shocking and awesome.” So we’re now congratulating ourselves for the scenes we’ve just written?

Or, right when Baby needs to break during a car chase, the lyrics for the current song are: “I’m gonna break, I”m gonna break!” A touch on-the-nose maybe?

Then there’s that name. “Baby.” It’s just dripping with try-hard pretentiousness. Every time I see it, I cringe. You know what the driver’s name in Drive was? He didn’t have one. That’s cool. This is, “Please oh please love my offbeat ironic character name!”

Assuming you can get past that, how does Baby Driver’s plot hold up? Well, it doesn’t. And I had a feeling it wouldn’t. You suspected that Wright loved this gimmick so much, he wouldn’t feel like he needed a plot. Indeed, there’s little variation to the beats of the story. We’re either in prep meetings, driving getaways, or watching Baby Driver go through his daily OCD rituals (which amount to getting coffee). That’s the playlist. And it’s stuck on repeat.

But my biggest issue with the script was Baby himself. Besides his entire backstory feeling extremely manufactured, I found him to be a clash between annoying and obvious. In one of the early prep scenes, the leader tells everyone the detailed plan, but one guy is concerned that the driver, Baby, didn’t hear it, cause he’s listening to music. So he says, “He didn’t hear it!” And the leader says, “Baby, do you know the plan?”

What do you think happens next?

Why, of course, because it’s the most obvious choice in the world, Baby recites the leader’s plan word for word. This is supposed to be the moment where we fall in love with Baby. All I could think was, “Really? You’re going to go with the exact beat that every person in the audience was expecting?”

And it’s surprising we get predictable moments like these because it’s clear that Wright went to town on this script. Despite not liking the style or the content, I can tell every word here has been meticulously combed over. You get the feeling that Wright’s been working on this for years.

Which makes me wonder if he overwrote it. Because that’s what it feels like to me. Something that’s almost too perfect. And, as everyone knows, when something’s too perfect, that’s exactly when it starts looking off.

I see Baby Driver as the antithesis of Drive. Drive’s coolness was that it just was. It could care less if you liked it or not. Baby Driver really really really wants to be liked. And that’s its biggest fault. It’s trying to become a classic before it’s even become enjoyed.

That puts me in a tough place because it’s important that movies like Baby Driver do well. So I badly want to endorse the script. But I can’t get past how try-hard it is. What I do want to do is see it in theaters this weekend. This movie was clearly meant to be consumed as a musical piece. So maybe the music will make me forget all about Baby Driver’s backed up transmission?

Here’s to hoping.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I did enjoy one scene in Baby Driver. And I’ll tell you which one. The team had just gotten back from a particularly gnarly job, and they end up at the diner Deborah works at. Nobody knows at this point that Baby visits this diner or that Baby has a thing for Deborah. So they’re all weirded out when Baby demands, “No, we’re not going in there. We’re going somewhere else.” Bats senses something is up. So he says, “Oh, now we’re definitely going in there.” And they all go inside and have a meal with Deborah as their server. The scene is interesting because Deborah had no idea Baby was mixed up with people like this. Crazy Bats is trying to figure out why Baby’s being protective of this place. Darling is sniffing out a romance. It was a fun scene with a ton of subtext. And guess what? It was also the only scene in the movie that didn’t depend on the soundtrack gimmick. All it was concerned about was being good. Coincidence?