I woke up this morning feeling like a bacterial army had stormed the shores of my brain. This is usually the result of a downtick in In N Out visits. I’ll have to remedy that. In the meantime, I need some TLC. So if anyone is in the Hollywood area and wants to come over, heat me up some chicken noodle soup, add bubbles to my bathwater, and give me a footrub, text me.

Speaking of TLC, I’ve been dong a lot of reading lately, paying particular attention to scene-writing, and noticed that a lot of writers are leaving good scenes on the table. Especially you TV writers. Remember that with television, you don’t have the benefit of spectacle or action. You need to keep our interest through good old fashioned drama. Which is why I’m leaving you today’s tip.

TSC

TSC stands for tension, suspense, conflict. Every scene you write should contain at least one of these three devices. Where a lot of writers get thrown is they believe that as long as they’re moving the story forward, the scene is okay. Oh contrere mon frere. You must not only move the story forward, you must do so IN AN ENTERTAINING WAY. And that’s where TSC comes in. It ensures that what the characters are doing is entertaining.

Tension is the easiest of the three to add. Teenage Sister talking to Teenage Brother about a ride to school is boring. However, what if Brother is dating Sister’s best friend? Now a discussion about a ride to school is laced with tension. This is exactly what they did in The Edge of Seventeen.

Suspense is a little trickier, but the most effective of the three options when used well. Staying with our high school theme, a test scene can be boring. However, what if, during the test, our student is waiting for his buddy to text him the answers? There’s only 10 minutes left. He keeps checking his phone. His friend still hasn’t texted. Will he get the answers in time?? SUSPENSE!

Conflict is the broadest of the three options and covers a lot of ground. Remember, conflict is not just characters yelling at each other. The trick to adding conflict is adding an element THAT MAKES THE SCENE DIFFICULT FOR AT LEAST ONE OF THE CHARACTERS. If the scene is easy for everyone, there’s no conflict. For example, let’s say Jimmy’s at a party and he’s about to approach his crush, Jenny. If these two get to talk freely, the scene will lack conflict. So what about bringing in Football Player Hank. Hank strolls in and starts talking to Jenny as well. This makes Jimmy’s plan to talk to Jenny MORE DIFFICULT, which adds conflict to the scene.

Conflict can be found everywhere as long as you’re looking for it. If I woke up and was feeling fine this morning, BORING. I woke up and was sick. All of a sudden my day is MORE DIFFICULT. Conflict!

There you go. Now get back into your scripts and start adding some TSC.

And somebody make me some soup.

No, this is not an April Fools joke. Another Amateur Offerings is here! Which means another opportunity for us to find an excellent script and propel a writer into the Hollywood stratosphere where they will surely forget about us the second they get a job in the Voltron universe writing room.

To submit your script for a future Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, why your script deserves a shot, to: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the ramifications of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or script title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every few weeks so your submission stays near the top.

The rules of Amateur Offerings are as such: Read as much of each entry as you can, then, in the comments section, vote for your favorite script. The script with the most votes gets reviewed next Friday. If that script is really good, there’s a chance the review will kick-start the writer’s career.

And with that, here are this weekend’s entries!

Title: The Inept

Genre: Dark Humor

Logline: Chaos ensues in quiet suburbia after Eddy finds a lost wallet and obsesses over how to return it and then win over its owner, the beautiful Lindsy Rocker.

Why You Should Read: Enter a world where dueling dildo fights, threats by midget bookies, baristas posing as psychiatrists, and mistaken identity over strippers with stomas simply represents a “bad week” for Eddy, a socially inept virgin obsessed with a photo found in a woman’s lost wallet.

Title: Surviving Maine

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Logline: A group of teenagers become lost on a road trip and find themselves trapped in a terrifying real life version of Stephen King’s Maine, where all his horror novels have mysteriously come to life.

Why You Should Read: I wrote this script for fun last year. At the start of this year a TV show called Castle Rock (J.J. Abrams/Hulu) was announced with a similar premise – bringing together lots of cool Stephen King stories. I guess I just wanted to get my script out there for a few people to read before it becomes completely irrelevant. That being said, the platforms I have uploaded the script to/the people who have read it, have all been quite positive with their feedback. I’m off to slap J.J. Abrams in the face. :)

Title: The Onus of Inspiration

Genre: Metacomedy/Drama

Logline: When two roommates both decide to start making their own movies, one being a documentary about the making of the other, turmoil arises as they struggle to come up with an idea. These two often stoned minds tackle inspiration and the difference between Hollywood and independent filmmaking as friendship turns to rivalry and back again.

Why You Should Read: I’m Liam McNeal, a twenty-year old film fanatic from Washington. I fell in love with the movies in 2010 when I saw Inception, and have been studying film history ever since. I’ve written three screenplays, but this is the only one I feel is worth anything. It’s very meta, being about a documentary about the making of a movie, but I used this script to express self-doubts about my own talent as well mock the fear of Hollywood filmmaking a little bit. It’s a mix of ideas that touches on a whole lot of topics related to film, and it is without a doubt worth your time. The main characters of Todd and Lewis have two different ways of thinking, but are both in love with film. I’ve drawn great inspiration from a wide variety of movies, and that’s evident in the screenplay. It’s admittedly quite long, but I believe that the movie won’t end up being three hours long, due to direction and editing. This is a screenplay I’m incredibly passionate about, and I hope that you can look at it and perhaps give some valuable critique, beyond ‘Make it shorter’.

Title: The Young Hollywood Party Massacre

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Logline: A young, hip Hollywood couple on the verge of becoming first-time parents begin to fear their unborn baby is a murderous demon.

Why You Should Read: I used to work at a major talent agency. During my stint there, my wife was pregnant with our first child. This script was written over that period of time. Horror comedies are hard to pull off. That, coupled with a story that lampoons, among other things, big talent agencies seems like a recipe for disaster for an amateur writer. Which is pretty much why I wanted to write it. Or “needed to” is probably more accurate: I had to find a way to channel some of the negativity I was feeling about the biz, living in LA and bringing a baby into that world.

Title: Alice

Genre: Dark Fantasy / Noir

Logline: In the warped underworld of Wonderland, a disgraced detective grapples with enemies and his sanity, on a destructive journey to discover what happened to the beautiful missing Dreamer he once loved.

Why You Should Read: It’s hard to climb up the never ending greasy pole that is the films industry, but I don’t need to tell you that… I’ve been trying it for a while and now, and attempting to ignore my slippery hands I have had a go at writing my latest feature film script: ‘Alice’. This is the one that I’m hanging my hat on and I’d love for it to be chosen as this week’s Amateur Offering. It may seem impossible, but I know a girl who thought of six impossible things before breakfast.

SPECIAL SCRIPT CONSULTING DEAL! – It’s the SPRING SCRIPTSHADOW CONSULTING DEAL. I’ll give the 1st, 20th, and 40th writer who e-mail me $150 off a screenplay consultation. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “SPRING DEAL.” Your script doesn’t have to be ready yet but you do need to pay to secure the deal. Hope to be reading your script soon!

One of the most heated debates in screenwriting circles is, should you or shouldn’t you outline? Bust that one out in a Los Angeles coffee shop and within half an hour, you’ll have 17 police cars surrounding the place and at least one screenwriter being dragged out of the venue without a shirt on screaming, “He didn’t even understand what an inciting incident was!!” Happens at least once a week in my neighborhood.

I’m a strong believer in outlining, as are most professional writers. I’d say about 90% of working professionals outline their scripts ahead of time. With that said, we are still talking about art here. And there’s no single way to create a work of art. For that reason, if you are anti-outline, I want to share with you the best way to write a script without one.

But before we do that, I want to talk about why professionals prefer outlining. You see, almost every screenwriter starts off thinking outlining is pointless. They write four or five scripts without one before realizing that, wait a minute, you actually spend more time rewriting a screenplay than writing one.

Once you understand that, you ask yourself, “What preventative measures can I take to lessen the amount of rewriting I have on the back end?” They figure out that if they can do more work on the front end, before they write the script, it can actually save them a lot of time when the rewrites start. And hence a belief in outlining is born.

One of the reasons it’s so difficult to write a script without an outline is that while you’ll have a general sense of your story ahead of time (where you want that character death to happen and how that plot twist is going to play out), it’s all very nebulous. And because it’s nebulous, once you start writing, you realize you don’t have nearly as much story as you thought you did. So you add that character death on page 20 and that plot twist on page 30. The next thing you know, you’re on page 45 and you’ve already written down all of your ideas. You’re now staring off a cliff of uncertainty, wondering where to take the story next.

Had you planned for that moment ahead of time, you probably would’ve been able to prevent it. And that’s why outlining is so helpful.

It’s so helpful, in fact, that I’m fascinated with why most beginners are so against it. So I started asking them. At first I got a lot of answers like, “It restricts creativity,” and, “It’s not real writing.” But when I pushed, I realized the answer was simpler. Most beginners don’t outline because they don’t understand the 3-Act structure. How can you outline if you don’t know the structure the outline will be based on??

That, then, becomes our first rule for writing a non-outlined script.

Rule #1: You need to learn as much about the 3-Act structure as possible.

I don’t care if you outline or don’t outline. A script needs structure. You need to be writing towards certain pillars in the story that are only there if you understand how storytelling works. The issue with most beginners is they only see one checkpoint in a screenplay, the end. Understanding the 3-act structure allows you to have multiple checkpoints, breaking the script down into more manageable chunks. The first act is the SETUP and takes up ~25 pages. The second act is the CONFLICT and takes ~50 pages, and the third act is the RESOLUTION and takes ~25 pages. The better you understand structure, the easier it will be to write your script in a non-outlined format.

Now, one of the big advantages to not outlining is that you’ll come up with more creative ideas. When one outlines, they’re looking at the script from a bird’s eye point of view. It’s hard to be creative from that perspective. You come up with your best stuff when you’re in the trenches, seeing the story through the character’s eyes. That’s where those ideas really pop. Which leads us to our second rule.

Rule #2: You must have an active imagination.

If you don’t have an active imagination and aren’t the super-creative type, don’t write a script without an outline. This type of of writing requires that you have a LOT of ideas. Remember, you haven’t mapped out your story ahead of time. You’ll inevitably be hitting a lot of dead ends. So you’ll need a steady stream of creative ideas to keep the story moving.

This leads us to our third rule, which is similar to the second, yet no less important.

Rule #3: Release all judgment.

This is ESSENTIAL to writing a non-outlined script (and when you think about it, it’s essential to writing any script). If you judge your writing when you’re working without an outline, you will bog yourself down and eventually give up. You must release any thoughts of “this isn’t good enough,” as “flow” will be your best friend when you haven’t outlined. Once the flow dies, the script stops. So you don’t want any judgement rearing its head, making your life miserable. Weird idea? Follow it. Bad idea. Take a chance on it. Release all judgement and keep those fingers typing!

Rule #4: Your first draft becomes your outline.

When you get to the end of your non-outlined script, guess what you have? You have your outline! That’s right. When you write without an outline, your first draft becomes your outline. Your job, now, will be to assess what you like and don’t like about your draft, write down the changes you want to make, go write your next draft, and THAT DRAFT will actually be your “first draft.”

As much as I believe outlining is important to writing a professional level script, I understand it has its drawbacks. Outlining can become a reason not to write, as you get bogged down in outline details instead of going in there and doing the actual writing. We’re all different. We all approach our creative process differently. As long as you understand the pros and cons of a method, you can make an educated decision on which option is right for you. If writing without an outline feels like your jam, I’m not going to discourage you from adding it to your sandwich. Just don’t punch the guy sipping the caramel macchiato next to you because he thinks theme is more important than character.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from Black List) A precocious young writer becomes involved with her high school creative writing teacher in a dark coming- of-age drama that examines the blurred lines of emotional connectivity between professor and protégé, child and adult.

About: If you weren’t paying attention, you may have missed Jade Bartlett’s script, which appeared near the bottom of last year’s Black List. Bartlett started as a playwright and occasionally acts, grabbing a bit part in last year’s, The Accountant. She’s looking to direct Miller’s Girl as well.

Writer: Jade Bartlett

Details: 121 pages

One of the things I’ve been struggling with lately is the balance between reality and cinematic license. Movies are a heightened version of reality and are therefore subject to a different set of rules than real life. A common example is that old movie setup of the directionless loser grabbing the attention of the hottest girl in town. Sometimes audiences just go with that stuff.

But I don’t see this as an excuse to completely ignore reality. Storytelling is still subject to suspension of disbelief. If your characters start doing or saying things that are too far removed from the realm of believability, the reader/audience will feel the writer’s hand, pull out of the story, and begin to observe it from the outside as opposed to where they should be observing it, which is from inside.

For example, I was originally going to review a script called “Coffee and Kareem” today, another Black List script about a 9 year old boy who teams up with a cop to take down a drug lord. It starts off funny, but at a certain point, the boy is joking about extremely advanced sexual situations that there’s no way a 9 year old boy would a) know about or b) care about. I’m talking: “As I suck the meat off yo clit, won’t stop till ya squirt” level situations. The writer went too far off reality’s path and the suspension of disbelief was broken.

Miller’s Girl never goes that far. But the script is a strange one, skirting that line so sharply that it was hard to take what I was reading seriously all the time. With that said, Bartlett’s unique voice and almost magical mastery of the English language ensures that Miller’s Girl is a rewarding experience.

Awkwardly pretty Cairo is a gifted 17 year-old writer. Her new high school creative writing teacher, Jonathan Miller, used to be a writer, but has since regressed to the point where he hasn’t written a word in years, hiding behind his teaching job as the reason he no longer pursues the craft.

Miller immediately recognizes how talented Cairo is, and the two start hanging out with one another after class, trading the occasional quote and seeing how long they can quip each other before someone says, “touche.” Needless to say, Cairo starts to become fascinated with Miller, and looks for more opportunities to spend time with him.

Meanwhile, Miller’s best friend and fellow teacher, Boris, has his eye on Cairo’s best friend, the gorgeous Winnie. Whereas Cairo is cerebral, Winnie is all about the physicality. And when she picks up on Boris’s interest in her, she milks it for every ounce it’s worth, basically broadcasting that he can fuck her any time he wants.

Things get complicated when Jonathan assigns Cairo to write a short story and Cairo writes up a Hustler article about a teacher who seduces a student. Horrified, Jonathan tells Cairo to destroy the story and reminds her that they are only friends. Feeling rejected, Cairo instead gives the story to the principal, resulting in a series of events that may destroy Jonathan’s career, and with it, his life.

First of all, there is no doubt that Bartlett is a gifted writer. I mean, when you read this, you will immediately notice the limitations of your own intellect. The woman is a wordsmith who has few equals.

But here’s what I mean about reality. Most of the conversations here, particularly the ones in the first half of the script, reek of a writer showing off her skills rather than one who’s trying to write the best story.

There are a lot of lines like this one: ”Can you keep a secret?” “I’m keeping Victoria’s in my pants. Does that count?” And while, on their own, these lines are harmless, when they’re strung together with 50 other variations of the same exchange, they stop feeling like real people and start feeling like, “Check out my dialogue skills, bitches.”

On top of that, there are moments where both our male teachers and 17 year old female students are hanging out before class and Boris will say to the girls something like, “So did you get laid last night?” I know I haven’t been in high school for awhile. But doesn’t that kind of question get you fired these days? When people say and do things that aren’t realistic, it’s inevitable that the reader will be pulled out of the story.

After I finished the script, I found out that Bartlett is also a playwright, and that made sense. I know dialogue is a big focus in playwrighting and that the idea is to go bigger and snappier. So maybe that explains some of the more outrageous dialogue. But in screenwriting, you have to watch out for that.

And, see, that’s the thing. When this script got really good is when it dropped the pretense and focused on the conflict. The best scene in the script happens on page 74 when Jonathan confronts Cairo about her short story.

Gone are the quips, replaced by a genuinely intense conversation. Every word matters. If Jonathan isn’t clear to Cairo that there’s nothing between them, he could get in some deep shit. But if he goes at her too hard, she could get upset and fuck him over anyway. So it’s a very delicate balancing act that goes to show – genuine conflict and drama is always better than trying to force something out of nothing. If you go into a scene without clearly understood directives from both characters, you’re going to be flailing around like a fish, inevitably trying to dress up a body that isn’t there.

It shouldn’t be a surprise, then, that that’s when Miller’s Girl really picked up. Things get dark fast and this script leaves you with a number of feelings – anger, frustration, confusion – that you don’t typically get from a read. Whereas Bartlett struggles to keep things truthful, she excels at coming up with situations that there are no simple answers for.

The hardest scene for me to read was Jonathan’s scene with his bitch wife after he’s been suspended. Holy shit was that intense.

If the same sort of truth and genuine conflict used in that scene could’ve been used throughout the first half of the script, this would’ve gotten an “impressive.” Still, while flawed, it’s a script that stays with you. And we all know how rare that is to find.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Playwrights moving to screenwriting – You have to expand your scope. While reading this, I didn’t get any sense of the school at all. This is likely because, as a playwright, you don’t have to worry about those things. But as a screenwriter, even though your focus will be on a handful of characters, you want to bring more of your surroundings in. We need to see other classes, meet other students, feel like there’s a real world to explore here. When your scope is too narrow, something will feel off about the story that the reader can’t articulate. That’s usually it. Bring in the rest of your world and the problem will be solved.

What I learned 2: The word “vituperation,” which means “bitter and abusive language.” I have never, in the 7000 scripts I’ve read, come across that word before. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to casually drop the word “vituperation” into conversation today and not get called on it. Let us know how it went in the comments!

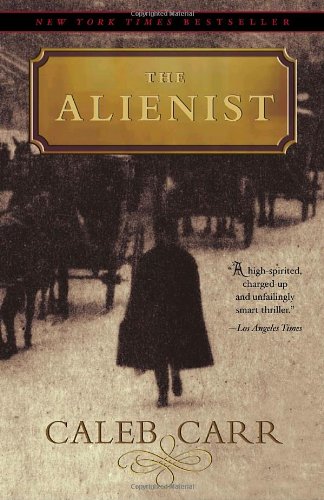

A period serial killer piece from the writer of Drive and the director of True Detective? Sign me up!

Genre: TV Pilot – Serial Killer

Premise: When a boy prostitute is brutally murdered in 1896 New York City, an “alienist” – a special type of doctor who studies mental pathology – attempts to find the killer.

About: The pilot for today’s show comes from powerhouse artists Houssein Amini (Drive), Cary Fukunaga (True Detective), and Eric Roth (Benjamin Button). It will star Daniel Bruhl (Inglorious Basterds), Luke Evans (The Hobbit), and Dakota Fanning. The show is based on the novel by Caleb Carr. The show will surprisingly air on TNT, which realizes that if it wants attention, it needs to get into the premium television business.

Writer: Houssein Amini (adapted from the novel by Caleb Carr)

Details: 66 pages

We’re in an interesting time with television. It reminds me of the reality TV craze that hit in the early 2000s where anybody who ended their pitch with “and it’s a reality TV show,” would get their show on the air.

But then, after 10,000 terrible reality TV shows hit the air, the ratings dried up, and no one was sure what to do anymore. Eventually much cheaper productions moved to ancillary channels. But for awhile there it was touch and go on what would happen with the format.

Right now there are SO MANY FREAKING SHOWS spread across SO MANY CHANNELS that casualties are a foregone conclusion. There just aren’t enough eyeballs to watch everything. And even when there are, you have to first find the shows, then find out where they’re on, then find out when they’re on. And how do you do that when all the high profile shows are saying, “Look over here instead!!”

You have guys like Matthew Weiner making some bonkers mega-budgeted show on Amazon. You’ve got the Tom Hardy show, Taboo, which is good, but the average viewer has no idea what it’s about. You’ve got this misconceived Ryan Murphy’s show, “Feud,” which is a 90 minute movie at best being stretched into a season of television. You’ve got award winning shows like Atlanta, yet I haven’t met a single person who’s actually seen it.

The Alienist fits into that mold. You have really smart creative people making this show. But it’s so dark and so intense, that to stand out amongst this endless list of competition is going to be darn near impossible unless the show is great.

So, is the show great?

Well, I know one way to find out.

Local newspaper reporter John Moore has been sent to check out a gruesome murder at the unfinished Williamsburg Bridge. “Unfinished” because this is 1896 New York. I’ll tell you who is finished though. The prostitute boy who’s been sliced open and had his eyes gouged out.

Moore, horrified by this sight, is only able to recover once his friend, Lazlo Kreizler, enters the fray. Kreizler is a new breed of psychologist called an “alienist,” whose main job it is to decide whether criminals are sane enough to be punished for their crimes. But Kreizler’s talents will have to be used for something far greater – catching a killer.

The two are indirectly helped by Theodore Roosevelt. That would be POLICE COMMISSIONER Theodore Roosevelt, in the job he held before racing up the political ladder. Roosevelt is a bit of a forward thinker, even hiring a young woman, Sara Howard, to work at the precinct – something that was unheard of back in the day.

Roosevelt realizes that this killer is way beyond anything the police force has dealt with in the past. But he also knows that if he allows an alienist on the case, he’ll be seen as a fool. So he assigns Kreizler and Moore to find the killer on the down low.

While Moore is more of an observer, Kreizler is the kind of bizarre soul who keeps jars of fetuses in his office. Of course, they’re going to need that bizarreness to take down the single most perplexing serial killer New York has ever seen.

A question I’m often asked is: What are differences between an amateur writer and a pro writer? Writers feel that if they can work off a defined set of rules, they can mirror what the pros do.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. As an amateur writer, you don’t know what you don’t know what you don’t know. I can tell you that the plot choice you made on page 54 doesn’t fit, tonally, with the rest of the script. Or that the supporting character you like so much is redundant. Or that the majority of your scenes don’t push the plot forward. But you don’t see that. To you, all of those things make total sense. And they’ll continue to make sense until all the mysteries of screenwriting open up to you, something that only happens by writing script after script after script, by reading script after script after script.

When you read a pilot like The Alienist, you are seeing a professional writer who knows this medium inside and out. The attention to detail here is as impeccable as Mozart concerto. The research of this period is as good as an historian’s. And the writing itself has a sophisticated edge to it. For example, we get this line: “The murdered boy kneels in supplication, the falling snow settling on his long hair and blood soaked dress,” instead of this one “The dead boy lays there, mangled and bloody.”

I also find that pros tweak a familiar situation so that it’s not quite like what we’ve seen before. For example, a common scene I run into is the john hiring the prostitute, and then, to show that our john is “likable,” he stops the prostitute from trying to have sex with him and, instead, “just wants to talk.” Fucking kill me if I ever read that scene again.

But anyway!

We meet John Moore with a prostitute and, as he’s having sex with her, he’s angry because she’s telling him that she’s in love with another man. At that moment, the madame bursts in and the girl “drops the act.” It was all a little game they were playing.

It was a small thing but the point is, I’ve read a lot of prostitute scenes, and the fact that the writer gave me one that I hadn’t seen before is what separates him from the standard amateur.

But the place where professionals really separate themselves is in the characters. They create characters who are complex and different. I’ll give you guys a little tip here to help you get closer to these million-dollar-a-project screenwriting studs – create characters with CONTRAST.

So here you have Lazlo Kreizler, who is into some really dark disturbing shit. As I mentioned before, he keeps fetuses in his office. And yet he’s always happy, always having fun. That contrast between the light and the dark is what makes the character interesting to watch. If Kreizler was into dark shit and he was also really depressed, his character would seem on the nose, or worse, boring.

That’s not to say you can’t create characters who are of one mind. You could argue that Rust Cohle from True Detective was into dark shit and also acted dark. What I’m saying is, contrast is an easy hack you can use to make a character pop.

And, actually, that’s my only complaint with The Alienist, is that the character of John Moore doesn’t have enough going on. Not as much time was put into him as was Kreizler. To be honest, I don’t even know why he’s in the story. Why would the police force, or even Kreizler, want a journalist hanging around? Isn’t that the opposite of what you want? Someone who might blab about your investigation to the local paper?

It would’ve been more interesting to pair Kreizler with the lone woman at the precinct, Sara Howard. At the time, women were barely allowed inside a police department, nor were they allowed to be exposed to gruesome murders. Imagine the conflict involved with her co-heading up this investigation with weirdo Kreizler.

Whatever the case, The Alienist should pull in people who liked that first season of True Detective. It’s just as dark, if not darker, than that beloved show.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You change the eyes, you change the view. One of the best ways to breathe new life into familiar situations is to change the eyes through which we’re experiencing those situations. If you give us a murder investigation through the eyes of a cop, you’re giving us the same thing we’ve always seen. But if you give us a murder investigation through the eyes of an alienist, now the exact same situations feel different. That’s because an alienist has a different set of objectives. They have a different set of criteria for why they do what they do. So the next time you come up with an idea, ask yourself how that idea changes depending on whose eyes you explore it through. You may find that a character you didn’t think twice about actually has the most compelling POV on the matter.