Congratulations to Poe’s “The Man of A Few Words,” which won this weekend’s Dialogue Short Script Mini-Contest. He wins a First 10 Pages Consultation from me. Poe’s a longtime kick-ass commenter so make sure to congratulate him!

Genre: Black Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) When an out-of-work divorced mother stops taking the court-ordered medication that made her feel like a zombie, her brazenly immoral, fifteen-year-old imaginary friend appears to help get her life back on track.

About: You may not have heard of Turner Hay yet. He broke onto the scene a few years ago, taking 3rd place (with a different script) in the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Awards, which is a big deal. Past winners include Eric Roth and Francis Ford Coppola, and they always have great judges for the competition (Billy Wilder, James L. Brooks, and Denzel Washington). Hay then got on the bottom half of the 2016 Black List with this script.

Writer: Turner Hay

Details: 111 pages

I am done being Complainer Carson for the week!

I am not going to complain about Academy Award winning screenplays that don’t deserve Oscars. Nope. Not gonna happen anymore. I am putting Complainer Carson on the shelf next to the salt and pepper and vinegar. It’s not going to be a part of this meal.

Instead, I am only going to regale you with positive stories, affirmations if you will. For example, did you know that Best Picture winner Moonlight only had a budget of 1.5 million dollars? That’s the equivalent of showing up to McDonald’s and trying to buy an entire meal for a nickel. It’s a ridiculous accomplishment for a film with that tiny of a budget.

Just for comparison, La La Land? Which, itself, is considered to be “low-budget” by Hollywood’s standards. Their budget was 30 freaking million dollars.

Oh, and Manchester by the Sea? Okay, yes, I did not like it, true. But you know what I did like? Kenneth Lonergan’s first film, You Can Count On Me. Great film. So I know the dude can write. Which makes it even more confusing why Manchester was so ba— CARSON! NO! NO, COMPLAINER CARSON! You’re not allowed here. Back on the shelf!

Before I get into any more trouble with my evil twin, let’s check out today’s screenplay and pray that it’s good enough to keep my weekly positive buzz going…

37 year-old Ivy Lydecker suffers from schizophrenia. And it’s not good, folks. She kind of may have killed her mother 11 months ago. Who was also crazy by the way. And the courts decided there was enough wiggle room in their scuffle that Ivy is allowed to live her life, as long as she takes a little blue “make the voices go away” pill every day.

Unfortunately, that pill makes Ivy a zombie. And when you’ve got a teenage son to take care of and an ex-husband who’s trying to permanently wrestle him away from you, being dead to the world isn’t ideal.

And so Ivy stops taking her pill. Which is how we meet Chloe, her cool-as-shit 15 year old imaginary best friend. The two clearly have a storied past, and Ivy would like nothing more than for Chloe to disappear. But it’s clear that no-pill and yes-Chloe are a package deal. You don’t get one without the other.

Chloe jumps into action, helping Ivy with her goal: prove to the courts she’s capable of taking care of her son. So Ivy gets a new job at a Securities Exchange, she starts dating a hot new restauranteur who’s a decade younger than her. She’s moving, she’s shaking. Things are happening in her life.

Oh, until that guy she’s dating ends up dead. And since Ivy already has a kind-of murder in her portfolio, the police want to know just how much she and this dude hung out. As the mystery thickens, Ivy’s new perfect life starts to crumble, to the point where she has to make a permanent choice. Keep living this wild lifestyle with Chloe, or go full zombie on the blue pill forever.

Bitter Pill-like scripts are interesting case-studies.

On the one hand, they do well on the Black List. The Black List likes inventive black comedies with fucked up main characters. Even more so if they’re women. There was a similar great script a couple of years ago called, “Cake.”

On the other hand, these films never do well at the box office. Even by low-budget indie standards, they’re tough sells. Cake, for example, made all of 2 million dollars, with a well-known actress in the lead role.

But going back to the first hand, these scripts are great career starters, regardless of whether the movie does well or not, as they display a strength in the one area Hollywood needs screenwriters for – the creation of compelling memorable characters.

Remember that suits can come up with concepts. They can come up with plots. The better ones can even beat out an outline. But nobody can write great characters except for good screenwriters. So when you break into the industry with one of these scripts, you prove that you have a highly valuable skill. You are the Liam Neeson of screenwriting.

So what is it that makes Ivy a strong character? For one, she’s battling something. Just by introducing a character who is battling an inner conflict, you’ve made a character that’s more interesting than most of the characters out there.

Step two is that the character is sympathetic, but not in a forced way. This is an important one so pay attention. Ivy has a son that’s being taken away from her. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who wouldn’t want to root for a mom that’s losing her son.

However, that’s pretty much the only box that’s checked on Ivy’s sympathy card. Ivy is selfish. Ivy is self-serving. Ivy is malicious at times. So because we have aspects of Ivy’s personality that are both good and bad, we don’t feel like we’re being pandered to. It’s that nuance that gives the character more of a “realistic” quality.

I remember reading a review for Paul Blart: Mall Cop when it came out. The reviewer pointed out that the first half hour of the film was dedicated to giving Paul Blart over a dozen sympathetic qualities to MAKE SURE that the audience loved him. That’s what you don’t want to do. You want to balance it out.

Creating nuance with just the right amount of sympathy, combined with some inner conflict – that’s the beginnings of a great character there.

And another way to build up a character is to make their inner conflict actually matter. Or, to use a well-known screenwriting term, add HIGH STAKES to it. So in the case of Ivy’s schizophrenia, there are real stakes if it’s found that she’s not taking her pills. She could lose custody of her kid.

And the reason that matters is because when we see her around other people and Imaginary Chloe is chatting away, we know that if Ivy breaks the ruse and talks back, she’s done. Her whole world will come crumbling down. This adds tension and uncertainty to every scene Ivy’s in.

My one big criticism with Bitter Pill is that I wish Hay would’ve put as much effort into Chloe as he did with Ivy. We’re told that Chloe is the cool girl at high school you were always afraid to talk to. Yet she talked pretty much just like Ivy, except with a little more attitude.

We discussed dialogue just this Thursday and Friday and one of the things that came up was utilizing dialogue-friendly characters. Chloe could’ve been a dialogue superstar. You get to play with a 15 year-old girl with no filter in a black comedy? You had license to go nuts with her. Yet her dialogue was restrained.

Anyway, not a huge deal. The script was still good. Just needs another couple of drafts to meet its full potential.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

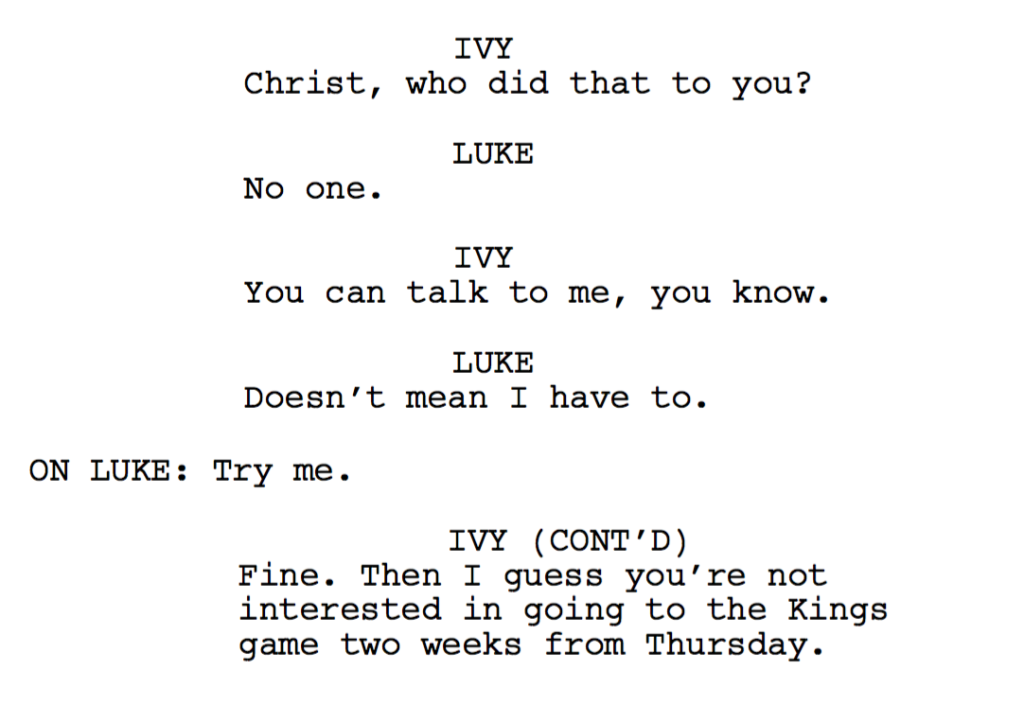

What I learned: This is a fun little dialogue trick. As you know, sometimes the best response to a line of dialogue is nothing. But you still want to convey a reaction – a specific feeling in the air from the recepient of the previous line of dialogue. In these cases, instead of writing the full reaction in an action line, which never quite flows the way you want dialogue to, write their name off to the side, a colon, and their feeling. Hay shows you how to do it here.

Wow.

So. Um. Okay.

Let’s get this out of the way first: Wow!

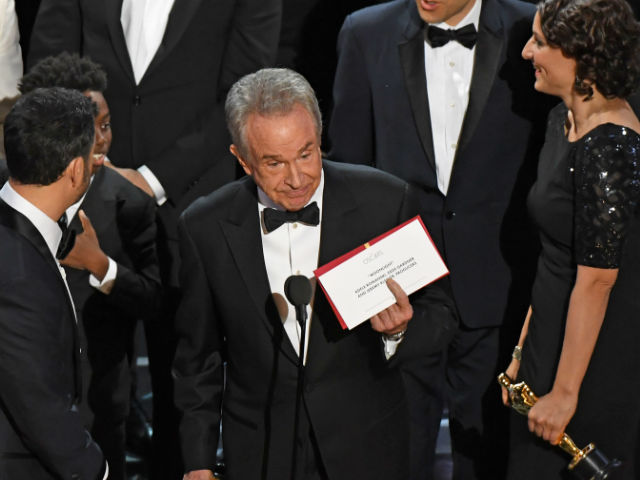

Only in Hollywood can an Awards Show have a twist ending.

Feel bad for the La La Land guys. “You just won best picture!” “Hurrrrraaaay! I’d like to thank my father, who’s up in heaven right now, my dying daughter, and Charlie, back in Jamestown, who’s suffering from MS. Charlie! If you’re out there watching, brother, I love you…” “Oh! Um guys!? Actually?? Don’t mean to interrupt your speech but we made a mistake. You lost.”

But you know what? I’m sure they’ll forget about it by tomorrow.

However, that’s the perfect entry point into my thoughts about last night’s Oscars, as Moonlight, La La Land, and Manchester By the Sea were the big winners of the night. And all three were the worst written films of those nominated.

Let’s start with La La Land. I’m actually happy this movie did well. I didn’t like the screenplay (I felt it was cliche at every turn that didn’t involve the dance numbers). But the thing about La La Land is that it’s a movie. If you’ve got singing and dancing, you have MOVEMENT on the screen. That’s why they’re called MOVE-IES.

Moonlight and Manchester By the Sea, on the other hand, had about as much movement as an Alaskan sunset.

But to be honest, I don’t have a problem with Moonlight winning Best Picture. I understand that when you’re talking about a film, you’re talking about everything that goes into it. The direction, the acting, the makeup, the cinematography. And it’s no secret that The Academy of Motion and Picture Sciences wants their winners to represent something bigger. Therefore, their nominees are heavily slanted towards social commentary and the human condition. So I get why the film won the big prize. Its message is, indeed, an important one that shines a light on a community that needs to understand that exclusion shouldn’t stop at race, but extend to one’s sexuality as well. I mean, we definitely need less cringe-inducing moments like this one…

However, what I do have a problem with, is when the Academy weights social commentary and the human condition to such a degree that those variables become more important than whether the film is actually good or not.

Moonlight and Manchester By The Sea won the Adapted and Original screenplay awards respectively. And they’re both terrible screenplays. There isn’t even a discussion to be had on the matter. They’re awful screenplays that display no skill in the screenwriting department whatsoever.

How can I say such a thing? One of the easiest ways to judge a screenplay is to ask, “Can someone else have written this?” Is the skill on display at a level where other writers could’ve written something similar? I can say without hesitation that there isn’t one writer of the 10,000 members in the WGA who couldn’t have written either of these scripts.

All you had to do was write a scene of a character who looks lost, write another scene where someone just died or got high on drugs, write another scene where the character looks a little bit more lost, write a few scenes where the character talks to other people, either about being lost or not wanting to admit they’re lost, then repeat that process for 2 hours. ANY WRITER can do that. It doesn’t take a lick of skill.

Screenwriting skill comes from the ability to convey your message through an entertaining dramatic narrative. It’s saying the things that those two movies are saying, without dragging you through an endless collection of melodramatic cliches that hit the same dramatic beat over and over again. It’s being unexpected. It’s taking you to places you didn’t think the story would go. It’s exciting you. Being able to do that? That’s storytelling.

Recent examples of this include Drive, The Edge of Seventeen, Nocturnal Animals, The Big Short, The Imitation Game, Hell or High Water, and Sicario.

Unfortunately, there’s a bigger issue at play here. And that’s that the industry has designed the narrative behind these movies so that if you disagree with their greatness, you are either a) racist/sexist/bigoted/etc. or b) stupid. It’s almost laughable in the case of Manchester by the Sea. In the handful of times I’ve asked people about this movie in a public setting, the response has been, “Oh, it’s so meaningful. It’s so intense.” Yet every time I’ve asked a person about it privately, the answer is always the same and sounds very close to this most recent response, which I heard last night: “That was the most boring movie I’ve ever seen. It had three good minutes in it.”

What the Academy tends to forget is that a work of art, no matter how well-intentioned, is never beyond reproach. Moonlight is a script that would’ve failed miserably had it been featured on this site for an Amateur Friday review. And rightfully so. It hides its weaknesses behind beautiful cinematography and strong performances. But when you strip those away, you have 20+ minute segments of a boy walking around in a neighborhood. I’m sorry but that’s not screenwriting. It takes zero screenwriting skill to write, “The boy walks down the street” for 20 pages.

And that’s just the beginning. Moonlight has one of the most passive heroes in Academy nominee history. The guy just stares out while everyone else around him acts. I’m fine with a passive character if the writer has a reason for them to be passive. But I honestly believe this writer didn’t know the difference between passive and active, which is one of the easiest ways to identify a writer who doesn’t understand the screenwriting medium.

I’m a believer that you can write any story you want, as long as you entertain us in the process. And that doesn’t mean you have to include dinosaurs. It means understanding and implementing the tenets of drama. Goals, obstacles, stakes, urgency, mystery, suspense, conflict. Give me a script that shows a mastery of those skills and you’ve got my endorsement for an Oscar nomination. But if all you’re doing is drudging through one passive melodramatic scene after another, I’m sorry, but you haven’t written a screenplay, nor are you a screenwriter.

It’s not surprising to me that both of these movies were writer-director projects. While that combo can lead to some great films, such as when Quentin Tarantino or Spike Jonez have the reins, it is a hack that allows really bad scripts to slip through a vetting process designed to keep slog-fests like these from ever getting in front of the public.

If you don’t believe me, go watch Manchester by the Sea and Moonlight and strip away all the Oscar shine. Watch them for what they are. Tell me they aren’t anything but movies you see so you can tell other cultured people that you saw them. Once this happens, a dance will begin. You’ll look into each other’s eyes, and if those eyes give you the green light, you’ll be able to confide that, “That was a really boring movie, wasn’t it?” If not, you’ll both have to pretend how profound cinema can be, keeping the secret of these screenwriting imposters alive.

Maybe one of these days, the Academy will start celebrating movies that were actually well written as opposed to well-intentioned.

A reminder that the deadline for the OFFICIAL SCRIPTSHADOW SHORT SCRIPT CONTEST, where the winner gets their script produced, is coming up soon! March 12th.

So keep working on your short scripts and get them in by then!

In the meantime, we’ll continue to practice with these mini-contests. Working off of yesterday’s dialogue article, this weekend’s Shorts Mini-Contest will tackle dialogue.

Your short script must contain three things.

1) At least one dialogue-worthy character.

2) A dialogue-worthy scene.

3) You not settling for average words, sentences, phrases.

Post your short in the comments (you can write the scene inside the comment itself or include a PDF link). Page count is open but I recommend staying under 7 pages. The winner will be determined by how many UPVOTES they get (Disqus allows you to upvote a comment – so please UPVOTE any short you really enjoy).

Contest ends Sunday at 10pm, around Oscar time.

Good luck to all. Now let’s see who’s the best dialogue writer on Scriptshadow!

I’m currently working with a writer on an understated psychological thriller. One of the issues in the script is that the dialogue is flat. Characters speak to move the plot along, offer information, reveal backstory, and occasionally tell us how they’re feeling. While this keeps the story moving, there’s a lifeless quality to the interactions that leaves too many scenes feeling empty.

I’ve poured over the script a number of times trying to figure out ways to spice up the dialogue before having an epiphany: Great dialogue cannot happen on its own. It requires great characters. Need proof? I want you to think of all the great dialogue you’ve heard in your life. Has there ever been an instance where a bland or uninspired character spouts great dialogue? Never, right?

This made me realize that the problem ran deeper than the interactions themselves. If the dialogue was going to get better, the characters would need to get better as well. But this brought up a secondary problem. Our psychological thriller was understated. Like the movie, “Room,” it wasn’t built for flash. Can you still write good dialogue within that environment? Or can good dialogue only exist inside flashier films?

DIALOGUE WORTHY CHARACTERS

A quick look through some of my favorite understated films confirmed my belief that good dialogue can exist anywhere. What I found is that, in all good understated films, the writer adds at least one “dialogue-worthy” character. “Dialogue-worthy” characters are characters who were born to spout dialogue. They’re the chatter-boxes, the brash, the “full of themselves,” the kooky, the flashy, the self-destructive, the bipolar, the hustlers, the preachy, the jokesters, the opinionated. Any personality type that lends itself to a lot of talking, or an interesting way of talking, is dialogue-worthy.

So if you look at the understated Hell or High Water, that movie has the crazy brother. He’s responsible for all the fun dialogue. If you look at the understated Room, you have the son. He’s the imaginative one who makes all the interesting observations. If you look at the understated Ex Machina, you have Nathan, the pompous opinionated CEO whose every word seems to be calculated to get a reaction.

So you can’t give yourself the excuse of, “Well, my movie is understated so I can’t have any flashy dialogue.” Not true. You can always fit a dialogue-worthy character into your setting. And that’s good news. Because while multiple dialogue-worthy characters are ideal (Rocky has five of them), all you need is one to make it work. That character’s dialogue will work as a line to fish good dialogue out of everyone else.

However, if you have no dialogue-worthy characters, if you have no one to introduce the spicy charged words that bring a scene to life, it’s like trying to make a fire without flint. You can fuck around with it as long as you want, rewrite the scene a million times over searching for that spark, but it won’t come because none of the characters were built to burn.

DIALOGUE WORTHY SCENES

Moving on, there’s another key component to good dialogue: DIALOGUE-WORTHY SCENES. A dialogue-worthy scene is a scene built to milk great dialogue out of the characters. The essential ingredient to these scenes is… say it with me now… CONFLICT.

There are two main types of dialogue-worthy conflict. There’s on-the-surface conflict and underneath-the-surface conflict. I’ll give you an example of both using a movie I just saw, The Edge of Seventeen, about a teenage girl who’s struggling to find friends and acceptance in high school.

In one scenario, Nadine’s best friend chooses to date her brother over being friends with her. Whenever Nadine confronts this friend, the conflict plays out on the surface, of the “I can’t believe you’d do that” variety.

Nadine also lost her father five years ago and her mom refuses to talk about it. So while she and her mom get into a bunch of disagreements about school and life, the real conflict is playing out under the surface, with Nadine upset that her mom never talks about her dad anymore.

So, to be clear, if you do not have both of these things working for you in a scene, it will be very hard to write good dialogue. You can try. But it will always feel like you’re forcing it. The characters won’t sound like themselves because they’re not acting like themselves. They’re desperately trying to sound like people who say interesting things because the person writing them wants to write “good dialogue.”

FLASHY DIALOGUE

Now that we’ve got that down, let’s talk about the final step. The words themselves. How to be Sorkin. How to be Tarantino, Hughes, Allen, Mamet. This, my friends, is where the rubber meets the road. Crisp flashy dialogue that pops off the page is the single most talent-dependent skill there is in screenwriting. Some writers just have a better feel for how people speak than others. Some writers are funnier than others, more clever than others, have a bigger vocabulary than others. These writers have an advantage over the rest of us. But fear not. I’ve just given you two HUGE tips in writing great dialogue that 99% of writers out there are clueless to. So you have the foundation to your dream home. Now let’s talk about furnishing it.

The first rule of writing flashier in-scene dialogue is to stop accepting average. If you accept average words, average phrases, answers, sentences, etc, you will never write exciting dialogue. It’s your job, as a writer, to dress things up a bit. To think beyond the obvious. Sure, anything a character says must remain in character. A by-the-book nun isn’t going to dish out lines like, “Shit motherfucker. And here I thought you were turnt.” But as we’ve discussed, you should’ve designed as many of your characters as possible ahead of time to deliver interesting dialogue.

Let’s try this out. Say your hero, BOB, a barista, is serving a girl he sees come in every day that he likes, JANE. Here’s their exchange…

BOB: Hey, how are you today?

JANE: I’m feeling okay. How bout you?

BOB: Just trying to make it to my next 10 minute break.

JANE: When is that?

BOB: In 30 minutes.

JANE: Well, good luck.

BOB: Thanks.

How boring is that fucking dialogue? Ugh. I want to throw up just looking at it. Let’s make a few changes here based on what we’ve learned. For starters, we’re going to make Bob dialogue-worthy. He’s a chatterbox. Doesn’t know when to shut up. Also, to add the necessary conflict, Jane doesn’t like Bob. She thinks he’s weird. On top of this, we’re not going to settle for average dialogue. Let’s see what that does to our scene.

BOB: Hey, how’s it going, you look nice today, wow, new phone? I love new phones. I got a new phone last year. I should probably get another one. The screen just cracked on mine and I can barely see anything on it. First world problems, amirite?

JANE: (stares at Bob, weirded out) Uh, can I get a coffee?

BOB: I sure hope so, (leans in and whispers, conspiring tone) Seeing as we’re in a coffee shop. By the way, just got a new roast in. Ethiopian. Supposed to be amazing. I haven’t tried it yet but Jerry says it’s killer.

JANE: I don’t know “Jerry.” Can I just get my coffee? Black.

BOB: Ooh, old school. I like that. (holds up hand for a high-five. she ignores it) I’ve been telling Jerry for months that we need to get rid of all these frappes and lappes. Keep it pure. Like the Ethiopians.

JANE: Right. So… can I pay now?

You may not be totally onboard with my weird sense of humor but I think we can all agree that the second iteration of this dialogue is a lot better than the first. And all I did was a) add a dialogue-worthy character, b) add a dialogue-worthy scene, and c) I didn’t settle for average. Following those three rules alone is going to lead to MUCH better dialogue overall.

The final final thing I want to talk about is distinction – creating the specific manner in which a character speaks. This specificity is what’s going to set him or her apart from every other person on the planet. Have you ever met somebody in real life and thought, “That guy’s a character.” That’s what we’re going for. We’re trying to create CHARACTERS. And that means doing a little prep work. Below are the six main variables that will bring out the best dialogue that character is capable of expounding.

Region – What region is your character from? If they’re from the South, they might speak in a slow friendly drawl. If they’re from New York, they might speak fast and loud. If they’re from a farm in flyover country, they might speak softly. Of course, you can flip all these on their head (a Southern man who speaks fast and loud) but use region as a starting point.

Socio-Economic Background – Someone who’s grown up in a rich suburb and had the highest form of education imaginable will speak differently from someone who grew up on the streets.

Slang – Slang is one of the key attributes to creating good dialogue. Whether it’s Rocky with his “Yose,” Vince Vaungh in Swingers with his “beautiful babys” or a teenage girl referring to everything in hashtags and acronyms. Slang can be your best dialogue friend.

Vocabulary – This is a subset of socio-economic background, but it’s important to know if your character has a huge vocabulary or a tiny one. A lot of the best dialogue comes from an extensive vocabulary or a colorful vocabulary. So vocabulary-rich characters are good. Also, know that you can go against type. Will Hunting was a street kid who had a bigger vocabulary than half the Harvard students he interacted with.

Speech pattern – Does a character speak a million miles a minute or does he take his time?

Speech frequency – Does a character carefully pick and choose when he speaks or does he burst into the conversation all the time?

Disposition – Is your character arrogant, like Steve Jobs? Is he bumbling, like Jack Sparrow? Is he cocky, like Han Solo? Charming, like Rocky? Philosophical, like Obi-Wan Kenobi? Is he cruel, like Scrooge? Is he idealistic, like Jerry Maguire? Disposition will have a big influence on what your character says and how he says it.

And there you have it. You want your dialogue-worthy character. You want your dialogue-worthy scene. You want to push yourself to write dialogue that’s more exciting than the basic words people usually say. And, finally, you want to use specific minutia to elevate the individual words, phrases, and sentences into something flashy.

I hope you enjoyed today’s article because this weekend, you’ll be writing short scripts that focus on dialogue. More on that tomorrow. See you then!

Genre: True Story

Premise: (from Black List) After losing his luster and respect in Hollywood, famed director Sam Peckinpah hopes to direct his next great film with financial backing from Colombian drug lords and brings along a novice screenwriter to write the film in Colombia.

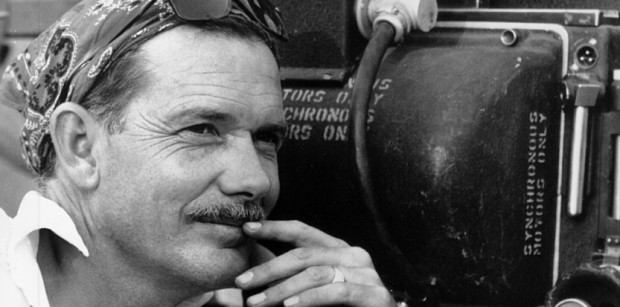

About: “If They Move Kill’em” landed on the 2012 Black List and was Kel Symons breakthrough screenplay. For those who don’t know, the subject of the script, Sam Peckinpah, was one of the best directors of the late 60s and early 70s, responsible for such classics as The Wild Bunch, The Getaway, and Straw Dogs. He was also a notorious addict who burned the candle at both ends AND in the middle.

Writer: Kel Symons

Details: 96 pages – 1st draft

Sam Peckinpah was the anti-establishment writer-director of his time. He hated… well, pretty much everything besides making movies. And to be involved in one of his films was like riding on a rollercoaster built entirely out of razor blades. While it may not have been enjoyable to be a part of the Sam Peckinpah legacy, you sure as hell came away with a lot of stories.

“If They Move Kill’em” is constructed around this conceit. It’s 1978, which was long after the apex of Peckinpah’s career. The Wild Bunch, his most famous film, was a decade old at this point. And while previous studio regimes had a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” approach to substance abuse, movies were becoming big business, and that meant more scrutiny at every level. Heck, Star Wars had just come out a year earlier. Everyone was starting to see what movies could become. Which made Peckinpah a relic of the old guard.

This is perhaps why Peckinpah decided to make his next movie in Columbia using 100% drug money. Peckinpah’s drug-fueled logic was this: Sure, I might be using blood-soaked hundred dollar bills to make entertainment, but at least I don’t have to answer to a bunch of self-serving liars in suits hell-bent on destroying my vision. The Columbians loved his Westerns. They’d let him do whatever he wanted.

There was only one problem. Peckinpah wasn’t making a Western. He was a making a commentary about the Columbian drug-trade, something he didn’t necessarily mention when all of the “financing” was being put in place. Therefore, when he flies down to Columbia to finalize the details, his drug-lord handlers are none too thrilled about this surprising turn of events.

Meanwhile, Peckinpah has hired a neophyte screenwriter, Charlie Stetler, to write his film. Charlie, a straight arrow with an 8 months pregnant wife, isn’t prepared for the world he’s dropped into. This is a man whose most exciting daily event is when the coffee machine breaks at the community college he teaches at. Now he’s walking through metal detectors with suitcases full of half-a-million dollars.

Peckinpah uses a steady diet of gin and tonics, whiskey, and Columbian coke to fuel the prep for his film. But when the Madero brothers, his financiers, learn that Peckinpah isn’t giving them the next Wild Bunch, they go apeshit and consider killing off the prick and his sidecar screenwriting act.

What scares the shit out of Charlie is that Peckinpah isn’t worried about this one bit! He’d rather challenge random drug lords to arm-wrestling matches than figure out a way to escape back to America before they get a bullet to the head. That’s when Charlie considers the unthinkable. Maybe this was all part of the plan. Maybe Peckinpah came down here to end his life in one final blaze of glory. And poor Charlie is just collateral damage.

Boy, this started out great. Peckinpah is one hell of a character. He is a feeding frenzy of drugs, alcohol, and women. He is a raging lunatic, a hurricane looking to sweep anything within a one mile radius into his circle of pain and loathing. And for that reason, whenever we’re highlighting Sam, the script works.

Where “If They Move Kill’em” runs into problems is in its plotting, as it never seems like Symons has much of a plan here. It’s almost like he’s hoping once we land in Columbia, the movie will write itself. In his defense, it would seem that way. He’s got this great character in this volatile setting. Why wouldn’t the script write itself?

Welcome to screenwriting. Where IT’S NEVER FUCKING EASY. Even when you think it’s going to be easy, it’s not easy. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought to myself, “Well, at least I have that one scene coming up. That scene is going to be amazing.” Then I get there and realize it’s the hardest scene in the script to write.

What “Shoot’em” reminded me of is that you still have to outline. You still have to plot. You still have to structure. Because if you don’t, your story just sort of drifts. It may drift into some interesting places. But it’s still drifting. The reason you plot is so your story can build – so that it moves towards an identifiable climax, something we can look forward to.

That’s the problem here. Where are we moving towards? Are we moving towards an agreement to make the movie? Is that the main character’s goal? We’re certainly not moving towards the completion of production, since 3/4 of the way into the script, we’re nowhere near shooting a frame of film. So the audience is asking, “What’s the end game here?”

How this hurts you is simple. You don’t know where you’re going so you just start writing shit down hoping for the best. About 70 pages in, for example, Sam and Charlie are sent off to a cocaine processing plant while the Madero brothers figure out what to do with them. And then we just watch our characters hang out.

You’re 3/4 of the way into your movie. Your characters shouldn’t just be “hanging out.” With 30 pages left in your script, we need to be building towards something. Especially when you’ve made a promise to the audience by chronicling this insane main character.

A great example of doing this the right way is The Wolf of Wall Street. That film has a clear structure. We see the rise of Jordan Belforte. Then we see the fall. We always know where we are. And, more importantly, we’re always MOVING. We’re never just sitting around waiting for things to happen. That’s the death knell of any screenplay. If your characters are waiting for anything for longer than a scene? You need to rewrite that section of the script.

Yet I wouldn’t give up on this project. Peckinpah is a person who’s worthy of being written about. He’s built for biopicing. I could see every actor between 50-60 dying to play him. Bryan Cranston would probably be the way to go. Maybe even Pitt. But this script is a reminder that a character isn’t enough. It’s a superb starting place. But you still need a plot with a plan. And I never saw that here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “innocent” thrown into the lion’s den is a great trope. Shonda Rhimes has built an entire TV empire around this setup. Remember that you’re always looking for conflict and contrast in storytelling. If someone’s in an environment they’re familiar with and/or comfortable in, that’s boring. But throw them into a world that they despise or are scared of, now you’ve got a movie. Peckinpah going to Columbia wouldn’t have been enough. He’s just as crazy as his hosts. But Charlie, the sweet and innocent screenwriter with a heart of gold being thrown into Columbia? Now you’ve got a movie. To test this, write a scene where a scheming drug addict walks into a strip club. I guarantee it will suck. Now write a scene where a bible salesman is dragged into a strip club. Watch the scene come alive.