Today I use this wild thriller to teach you how to write better action sequences.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: When a crossword puzzle maker finds out his dead father hid a code inside of him, he must figure out what it means before a pissed off CIA finds him first.

About: I keep seeing this name in the trades wherever I turn. “Joby Harold.” He wrote the King Arthur remake. He wrote the new upcoming Robin Hood movie. He just signed on to rewrite DC’s new Flash movie. “Who is this writer??” I’ve been saying every time I see him. A little research shows he wrote and directed the Hayden Christensen movie, “Awake,” back in 2007. But he hasn’t done much since. I traced his re-rise back to this script, which he wrote in 2011. Let’s find out why this got him back on Hollywood’s radar, and led to him being one of the hottest screenwriters in town.

Writer: Joby Harold

Details: 114 pages – 2011 draft

This week’s going to be fun. Tuesday through Friday I’m going to review the Top 4 scripts from the Scriptshadow Tournament, with the winning script, The Savage, getting the final, Friday, review.

But that leaves an open slot for today. And while I’d love to use that time to discuss the box office battle that was Split versus A Dog’s Purpose, I’ve opted instead to figure out where Joby Harold came from.

Whenever you’ve got a guy tearing up the assignment circuit, you want to know what their secret is. I’ll save you the suspense though, since I already know the answer. You get big assignments in a genre because you wrote something good in that genre. This is an actiony thriller script. He’s writing actiony blockbuster scripts.

But what about the content? What’s inside this script’s walls? Is it good? Will it help me forget my unhealthy obsession with the Split versus A Dog’s Purpose box office battle? I hope so.

Jake Richmond lives a quiet existence in San Fransisco writing crossword puzzles for The San Fransisco Post. He’s divorced with a young daughter, Emma, who’s the apple of his eye. Unfortunately for Jake, his past is a rotten apple. He was found on a boat when he was a toddler and has no idea who his parents are.

Then one day, while riding on the subway, an old man notices the unique cross Jake has around his neck, the cross that was found on him as a child. He lets Jake know how rare the cross is and encourages him to come to his museum to learn more about it.

Jake does, reluctantly, and it’s there that the man finds a little trap door within the cross, where a teensy-tiny scroll comes out. On that scroll? A phone number! They call it, where a 35 year old message tells him who his parents were and that Jake’s carrying something valuable inside his body.

The lousy news is, the CIA stole the device designed to receive that call, and they want to kill Jake just like they killed Jake’s dad! Why? We don’t know yet. But we get the feeling Jake knows something big. Or, at least, he will once he pieces together the puzzle his dad left for him.

That puzzle leads him all across the United States solving all sorts of weird puzzles. For example, at one point, Jake has to cut himself open to receive another clue, which is a long string with tiny knots in it. Those knots? They’re morse code, motherfucker!

On another occasion, Jake is given a series of directions that takes his car in every which way, making dozens of turns that make no sense. That is until after he gets to the destination – a storage facility – and needs to know what number locker to open. Zoom out. The number was traced via the path he just took with his car!

All the while, Jake is being followed by a mysterious CIA operative named Mr. Poe, who has a creepy Marathon Man-y vibe to him. Jake’s only hope of surviving this chaos is to find out what his dad was hiding from the CIA and use that knowledge to bargain for his life.

The Key Man is an old-fashioned mystery-on-the-run thriller. And mystery-on-the-run-thrillers are tough to write because there are only so many ways to write the “on-the-run” stuff, and the “mystery” stuff requires a hell of a lot of intelligence and creativity to come up with anything fresh.

Typically the way these scripts work is they start off with one good puzzle component, then each subsequent component gets cheesier and/or dumber. And that’s because we, as writers, are inherently lazy. So with each subsequent mystery, we’re less motivated to write something as good as the last one.

The initial component in The Key Man is that the first clue’s been surgically implanted inside Jake’s body. This leads to the best set-piece of the script, which is Jake holding a nurse hostage and making her perform surgery on him to retrieve the clue.

Unfortunately, this is where the mysteries go downhill. A string with knots acting as morse code felt a little… I don’t know, far-fetched? And then we’re deciphering that code to come up with a long string of numbers and letters, which we eventually learn are directions (the letters are direction and the numbers the number of blocks to go).

Look, I’m not going to rail on Harold here. I’ve tried to write these things myself and they’re really fucking hard. If you can come up with a COUPLE of good clues/mysteries, you’re doing a good job. But these scripts have 7 or 8. And unless you have the endurance to stick those out and be creative with each one, you’re not going to write anything good.

And really, this is a lesson for every genre. One of the biggest reasons that bad screenplays happen is lack of effort. The writer knows their choice for this next scene or this next sequence isn’t great, but they tell themselves, “It’s good enough.” Once you start using that phrase (good enough), you’ve lost the battle.

Another thing I want to bring up here is the difference between simple action and structured action. Simple action is straight forward, no brains necessary, action. This is how The Key Man starts. We’re following this couple and their child as they run from the CIA. However, THAT’S ALL THAT’S HAPPENING. It’s linear, it’s straightforward, it doesn’t require anything from the viewer.

Structured action is when a story is built into the action. There are multiple threads going on or a complex problem involved or a character conflict that’s agitating the scene, or all of the above. Audiences like structured action because it ENGAGES them on more than just a “look at all the flying colors” basis.

A good structured action scene is the plane crash in the movie, Flight. Before there’s even a problem, you have a drunk pilot. That adds complexity to the issue. Next you have a set of broken hydraulics, which make it impossible to control the plane. Then you have a young co-pilot who’s freaking the fuck out. So we gotta calm him down. Then we realize that the only way to save everyone is to pull off an impossible flight maneuver that’s never been attempted before (turn the plane upside-down). There’s no guarantee that will work. So it’s an all-or-nothing proposition.

You can tell that this crash sequence has been THOUGHT THROUGH. There are things going on on multiple levels, giving the scene a three-dimensional structure. The simple action version of this scene would’ve been, one pilot, an engine problem, and an attempt to make an emergency landing. And that would’ve been it. I suppose it could’ve worked. But how exciting would that have been?

Anyway, getting back to The Key Man. This script had some fun moments but it never rose to a level that allowed it to overcome this conceit: a father leaves his son a dozen impossible-to-solve puzzles to find what he left him. Why not just put the answer in the initial necklace note and call it a day?

Of course, you could make a similar argument for movies like National Treasure. So maybe the problem’s me. I crave a more sophisticated and believable puzzle to get me going these days.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Almost all of your action scenes should be STRUCTURED. What I often find is that the writer will structure THEIR MOST IMPORTANT action scene (so the featured plane crash in “Flight”) and then go with simple action scenes the rest of the way. Take the extra time and structure ALL your action scenes. I promise you your script will be better for it.

Note: The Scriptshadow Tournament winning screenplay, The Savage, will be reviewed next Friday. I’m actually going to review all tournament semifinalists next week from Tuesday – Friday.

It’s time for the Scriptshadow Short Screenplay Contest!!! And with this one, we’re going to do something different. Whoever wins, I’m going to team with a director to produce your short. We’ll also debut it here on the site. Yahoo!!!

I already know your first question. “How many pages does it have to be?” I’m going to strongly recommend 8 pages or less. But if you have an idea that’s absolutely fucking amazing, I’m willing to extend the maximum page length to 15 pages. I’m just going to warn you though, longer scripts will be discriminated against. There are very few short films that play longer than 6 minutes online and do well. So go over 8 pages at your own risk.

If you’re unsure what you should write about, check out this post I made last week about how to write a great short film. Not only does it have some good tips in there, but it has links to some really great short films. The comments sections is also packed with reader recommendations. A great resource for getting inspired.

I admit that, in an ideal world, the winning short will hint at a bigger story that can be turned into a feature film, as if this short does well, it will be easy to get funds to turn it into a feature. However, I don’t want that limitation to stifle your creativity. I just want the best story, regardless of whether it has feature potential or not. WRITE THE BEST IDEA YOU’VE GOT!

Everyone gets TWO script submissions. Submissions begin TODAY and will go for SIX WEEKS. Knowing that, here’s what I would do if I were you. Write AT LEAST five shorts. Then, trade reads with as many writers as you can. Ask them what they like best. Get a consensus on which shorts are your best and submit those. If you don’t have anyone to trade reads with, use the comments section below to look for feedback partners.

CONTEST GUIDELINES

1) Submissions begin today, January 26th.

2) The deadline is 11:59pm Pacific Time, Sunday, March 12th.

3) Send all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com (subject line: “SHORT SCRIPT”)

4) Your submission should include.

The title of your script.

The genre of your script.

The logline of your script.

A PDF attachment of your script.

5) You can submit a total of two short scripts. If you are caught submitting more than two scripts under separate e-mail addresses, you will be immediately disqualified from this AND all future contests.

6) Page length…

Recommended number of pages: 8 or less

Maximum number of pages (anything over won’t be read): 15

7) Eligibility Rule #1: Represented writers (writers who have a manager or agent) are eligible.

8) Eligibility Rule #2: You are not eligible if you have made more than $10,000 as a screenwriter. This does not apply to contest winners, however. You may still submit if you’ve won $10,000 or more in screenwriting contests.

9) The winner will be announced on a date to be determined later!

GOOD LUCK AND START WRITING!

When you start out as a screenwriter, it’s a bit like being dropped into the middle of the Atlantic on a life boat. You have a vague sense of how to survive for the time being, but you have no idea how you’re going to get to shore.

When I started screenwriting, I remember spending an endless amount of time on things that I would find out, many years later, weren’t nearly as important as I thought they were. If only I could go back and communicate with that young man, I could’ve opened up 15 hours a week for him. 15 hours that could’ve been used for, you know, having a life.

Luckily, I’m going to make sure you don’t make the same mistakes I did. Here are 10 things that you need to stop obsessing over.

1) Agents – While agents will be important later on in your journey, they’re not important now. An agent won’t be able to do anything with a beginner’s script. They won’t even be able to do anything with an intermediate script. Agents are mainly built to manage the career of writers who have one. You don’t have one yet. Focus on getting better. Enter contests. Try to get your script reviewed here. Get a consultant who can tell you where you need to get better. Self-publish a book. Write and direct your own short. When you’re ready, the agent will come. I promise you that.

2) Description – I used to spend hours – fucking HOURS – trying to get one descriptive paragraph just right. I got news for you. Readers don’t care about poetic description. They just want a clear sense of what’s going on in the scene. I have yet to see a script sell “because it had great description.” All that matters is that you have a compelling story unfolding. So focus on that.

3) Flashy writing – Damn you Shane Black. Anybody who got into the game in the 90s knows how Black’s flashy writing inspired countless screenwriters to try and break in with a coked up self-referential writing style. Who cares about story when you’re writing lines like, “Joe shoots his gun like he’s fucking your wife, a one man wrecking crew who’s so cool he’s probably reading this script right now while taking a shit.” No. Just no. Flashy writing is the essence of screenwriting insecurity. You’re scared your story and characters aren’t enough, so you try to distract everyone with a bunch of pixellated fireworks. Every once in awhile a writer comes along who makes this style work for his script, but usually it’s just a prelude to screenwriting embarrassment.

4) Action, action, and more action – I used to think that whenever your script was getting slow, you could add an action scene and immediately you’d have the reader’s rapt attention. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. What keeps readers interested are compelling characters that we care about and want to root for. If you do that, you don’t need a single action scene to keep the reader invested.

5) If you have a great concept, you can phone the execution in – Pay attention because this one runs a little deeper than you think. I don’t believe any writer purposefully phones a script in. However, when you have a great idea, you don’t hold yourself to the same standards as you do when you have an average idea. I used to write these high concept scripts that ended up being so bad because I didn’t put enough into the execution. I always went back to, “Well, I don’t have to be perfect because they’re going to love this idea so much.” A good concept is only a starting point. It gets you in the party. But it’s still going to take some work to get that beautiful girl’s number. The name of this game is, and will always be, keep the reader’s interest from page 1 to page 110. They may jump into your script excited as shit. But if you’re half-assing it, they could be bored out of their mind as early as page 10.

6) Outlining is for idiots – I’d say 90% of new screenwriters believe this. I’d also say 90% of working screenwriters outline. You tell me which segment has it figured out. The number one reason you run out of screenplay by page 50, 60, or 70, is that you don’t outline. Like it or not, screenwriting is the most mathematical of all the long-form writing mediums. A script is 110 pages long and 3 acts, which means you have to space things out proportionately to hit the requisite plot points at the right time. Outlining is the most effective way of doing this.

7) Dialogue is the most important thing about screenwriting – Dialogue is just the easiest thing to discuss, laud, or criticize. So it gets the most mainstream attention of all the screenwriting elements. That’s not to say dialogue isn’t important. But the underlining levers and pullys that are moving your story or your scene along are way more essential to writing something good. Take the Big Kahuna Burger scene in Pulp Fiction. Wonderful dialogue. But the dialogue wouldn’t have mattered if we didn’t have the suspense of whether they were going to kill this guy or not. If similar dialogue would’ve been used while they all sat around and enjoyed playing a video game, nobody would be talking about how great the dialogue was because they’d be bored by the scene.

8) Your main character has to have a flaw – I thought this for so long. Why shouldn’t I have? It was taught in all the screenwriting books. The truth is, a flaw is just one thing you can add to a character to give them dimension. But that doesn’t mean it’s the only thing. As long as your hero has some kind of unresolved inner conflict – like not being able to get over the death of someone (Manchester by the Sea), or they’re consumed by a vice (Flight) – that may be enough to create a compelling hero. I will say that SOMETHING should be going on underneath the surface of your hero if you want to make them compelling. But a fatal flaw is not the only option.

9) Sadness is the best way to extract emotion from the reader – I always thought if a character was sad or depressed, that the audience would feel the same way. It doesn’t work like that though. With enough sadness and depression, the reader gets impatient, eventually cracking: “For the love of God! We get it! They’re sad!!!” The best way to produce emotion is to take the reader on a ride. Bring them up (character experiences a high) then bring them down (characters experiences a low). Make them laugh. Then make them cry. Pixar is wonderful at this, which is why their screenplays are so well liked. A screenplay should work as an emotional rollercoaster.

10) Break lots of rules cause Hollywood’s movies suck – Everyone who’s at least 5 scripts deep in their journey knows what I’m talking about. Everyone’s written that 150 page behemoth, INSISTING that every page is necessary. Everyone has ignored the 3 act structure or defied every convention they could locate. If Hollywood makes movies like 9 Lives and Paul Blart, they argue, then there’s obviously a way to do it better. And you (the screenwriter who’s never written a script before) knows the secret sauce. Unfortunately, because you don’t even understand why these rules are in place, all you’re breaking is the reader’s trust. They see that you have no plan, no concept of how to write properly, and they immediately know (I’m talking within 5 pages) that your script will be terrible. Do not break any rule until you understand why it’s there in the first place. Otherwise you’re just flying a big flag over your head that reads: “BEGINNER SCREENWRITER HERE!”

Today we look at an old Blade Runner 2 script and get an idea of what the sequel to the cult classic might look like.

Genre: Science-Fiction

Premise: When an old blade runner flies into Los Angeles to find someone who can save his dying soul mate, he’s targeted by a young breed of blade runner who’s tasked with taking him out.

About: If there is a project that more exemplifies “Development Hell” than Blade Runner 2, I’d like to know what it is. Over the past 25 years, the project was happening, then it wasn’t, then it was, then it wasn’t. Harrison Ford was involved, then he wasn’t. Ridley Scott was involved, then he wasn’t. Well the project has finally come together with one of the flashiest packages Hollywood can offer. You’ve got Harrison Ford reprising his role. You’ve got Ryan Gosling playing the young blade runner. And you’ve got Denis Villeneuve (Arrival) directing. It should be noted that this is a 1997 draft of the script so I have no idea if they’re using the same plot or not. A novel for Blade Runner 2 was written, which is what this draft is based on. The writer, Stuart Hazeldine, has been pretty absent in Hollywood since he wrote this draft, until recently when he just got a huge directing gig with The Shack.

Writer: Stuart Hazeldine (based on the novel BLADE RUNNER 2 by K.W. Jeter)

Details: 126 pages (November 1, 1997 draft)

Okay, real talk.

Blade Runner is a visual and aural masterpiece and one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made. There’s no disputing that. The iconic shot of a car flying towards the giant exterior television with the Vangelis soundtrack playing in the background? Magical.

HOWEVER.

From a screenwriting standpoint, the film leaves something to be desired. Narratively, it starts out strong, then wonks around through a casual second act, before sort of coming together at the end. The reason given for why Blade Runner was never popular with audiences was that it was too “edgy” or too “dark.”

B.S.

In reality, the screenplay wasn’t very good. A stronger story would’ve meant stronger word of mouth which would’ve meant more people seeing the film.

Look at Arrival (ironically directed by the same person who will be directing Blade Runner 2). Offbeat sci-fi film that’s been a box office bonanza built entirely on word-of-mouth.

I guess that’s what makes the movie unique though, and like an obscure band, it’s always more fun to prop up what others don’t like. Will Blade Runner 2 change the narrative, or keep the offbeat sensibilities of the first film?

It’s been a decade since we last saw Deckard, our former LAPD blade runner who’s now hiding in the countryside with Rachael, the replicant he fell in love with. Replicants are only supposed to be able to live four years. But Deckard has built a cryo-chamber that’s extended Rachael’s life.

Unfortunately, even with life extension, Rachael’s going to die soon. That is, unless, Deckard can find someone who knows how to hack the “life limitation” code inside replicants. So he heads back into dangerous Los Angeles to visit an old friend who may be able to point him in the right direction.

Meanwhile, Deckard’s old boss learns that he’s back in town. Since aiding a replicant is illegal, he tasks a snazzy new blade runner, Andersson, to find and kill Deckard. In case you were wondering, the extra ’s’ in Andersson stands for “slick.”

Deckard’s journey leads him back to the Tyrell corporation, the place that makes the replicants, where a new woman named Sarah is now running the company. Sarah tells Deckard she wants him to finish the job he started a decade ago – find and kill the sixth replicant. If he does that, she’ll give him the key to extending Rachael’s lifespan.

And so the race is on. Deckard has no idea who this replicant is or what he looks like. But he must find and kill him before a determined Andersson finds and kills him first.

Blade Runner 2 has a traditional story setup. Deckard’s “wife” is dying. So he agrees to “one last job” in order to save her. What’s unique about Blade Runner, though, is the replicant twist. The person our hero is trying to take down could be anyone. Hell, he could be the guy staring back at you in the mirror.

Also, as with every good story, you want to add urgency if possible. Deckard running off and trying to find a replicant unimpeded is fine. But not as exciting as if Deckard is being chased by a cop who’s trying to kill him as well. Every moment is heightened when there’s someone on your heels.

A lot has been made of Blade Runner’s unapologetic darkness. As we all know, the word “dark” gets geeks more revved up than an IMAX preview of a new Christopher Nolan film. It is the operative word for cinephiles getting hot and giggly. It doesn’t matter if a sci-fi film is TERRIBLE. If it’s dark, there will be geeks who stand by it til the end.

One of the distinguishing characteristic between a dark and a “light” movie is the goal of the protagonist. If the protagonist is attempting to KILL someone, the overall tone of the movie will be dark. If the protagonist is trying to SAVE someone, the overall tone will be light.

What’s the goal of the original Blade Runner? – Go and kill some dudes. What’s the goal of this new one? – Go kill the final replicant. We even have a SECOND blade runner being tasked with trying to kill our hero.

Hollywood knows that darkness equals less box office, so they’re always fighting back against these narratives to give them some light. For example, Deckard is doing all of this to SAVE SOMEONE’S LIFE. This offsets the darkness a little, improving the chances that more butts show up in seats.

I think that’s why one of the darker movies in history, Silence of the Lambs, also made a ton of money. Yes, Clarice was tasked with (essentially) killing a man. But she’s also trying to save someone as well. They found the perfect balance in that story.

In comparison, did any of you see that 2010 movie, Edge of Darkness, starring Mel Gibson? You probably barely remember it if you did. That’s because the movie is about a dude who wants to kill the people responsible for killing his daughter. It’s dark and sad because it’s solely about killing. There is no light.

And therein lies the quandary. You get “street cred” as a writer for going dark. But you get money and jobs for going light. It’s why writers are obsessed with straddling that line to find the perfect balance – writing the next Silence of the Lambs.

Getting back to Blade Runner 2, this script, from a storytelling perspective, is actually stronger than the first film. It has more going on. But that doesn’t mean the film itself will be better. Blade Runner is one of the top 5 directed sci-fi films of all time, maybe top 20 directed films of all time period. From a DIRECTING perspective, it’s amazing.

So if Denis is able to capture that same magic, and he rides this more active plot (assuming they’re doing something similar) he may achieve what Scott could not – a dark movie that also breaks through to the popular masses.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re struggling with a tone that’s too dark, add more saving!

Note, to read Monday’s script review, scroll down or go here.

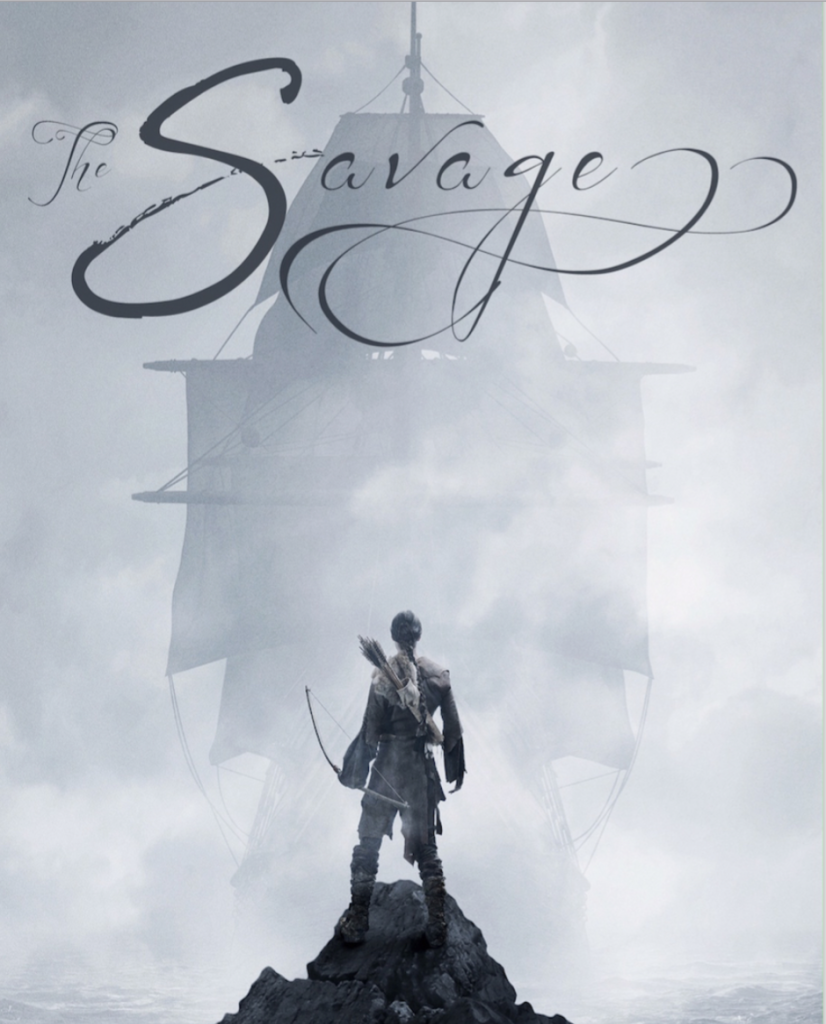

THE SAVAGE!!! BY CHRIS RYAN YEAZEL!!!

Genre: Historical Biography

Logline: The incredible true story behind one of America’s founding myths. After being kidnapped from his lands as a child, the Patuxet Indian Squanto spends his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that changes the course of history.

You can download and read the script yourself here:

For those coming across this tournament for the first time, I wanted to try something different. Instead of doing the traditional screenplay competition thing where you send a script out, wait four months, and desperately hope to get that e-mail that says you’ve advanced, I wondered what it would be like to play the competition out publicly. Not only that, but to have real people vote on the scripts. Not a couple of overworked screenplay competition readers.

A little over 500 scripts were submitted. I then chose 40 of those to partake in the competition. And via tournament-style elimination, the scripts fought against each other one round at a time. The Savage, which went in as the top ranked script, came out as the top ranked script. That’s better than Andy Murray can say at the Australian Open.

I want to take a moment to congratulate the runner-up, Billie Bates, and her script, The Bait. Billie had a strong showing all the way up the final, winning all her rounds soundly. And I want to thank and congratulate everybody who participated. This was such a unique experiment. I know it got bumpy at times. But overall, I had fun with it. I’m actually curious about what kind of changes you would make if we did the competition again. Please share your thoughts in the comments.

I will be reviewing The Savage this Friday. One of the hardest things about this contest was not getting too caught up in the script discussion. I knew I’d be reviewing one or more of these scripts eventually, so I didn’t want to know too much going into the reviews. FINALLY I get to see what all the hype is about.

Once again, congrats Chris. Amazing job. And, oh yeah, start getting those short scripts ready people!