THE WINNER HAS BEEN ANNOUNCED BELOW

SEMI-FINALS BABY!!!

The Final Four. March Madness. The Fearsome Foursome.

Down from over 500 entries, these four scripts are all that remain. Today’s scripts had to scratch and claw their way to this semi-final, each winning by less than 2 votes. I can only imagine what will happen this weekend.

A recap for those of you unfamiliar with the tournament. The first round went for 8 weeks, with you, the readers, voting for the best script each week. Those 8 winning scripts, plus 4 wild-cards, competed in the Quarterfinals. The 4 winning scripts from each quarterfinal are now competing in the semis, which is this week and next week.

Here’s how voting works. Read as much from each script as you can then vote in the comments section which script you think deserves to advance to the FINALS. Please explain why you voted for the script. It lets us know that you read the screenplay.

Today’s writers have new drafts. I’ll let them discuss the changes in the comments. Voting closes at 10pm Pacific Time Sunday evening.

#1 SEED

Title: The Savage

Writer: Chris Ryan Yeazel

Genre: Historical Biography

Logline: The incredible true story of Squanto, the Patuxet Indian who was kidnapped from the Americas as a child and who then spent his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that leads to one of the most significant events in American history.

WILD-CARD

Title: Cratchit

Writer: Katherine Botts

Genre: Mystery & Suspense/Fantasy/Horror

Logline: “A Christmas Carol” reimagined, told from the point of view of Bob Cratchit as he and Ebenezer Scrooge race to track down Jacob Marley’s killer — the same killer who now targets Scrooge as well as Cratchit’s son, Tiny Tim.

WINNER OF SEMIFINAL WEEEK 1: The Savage by Chris Ryan Yeazel! Congrats to Katherine, whose script was probably the hardest working in the tournament. Every time you thought it was out, she’d kill it with a rewrite and it’d be right back in contention. And, of course, congrats to Chris, whose #1 seeded script is like the Duke of March Madness. A powerhouse every time up. We’ll see who he’s going up against in the finals next week. Seeya then!!!

It’s 2017. You’re wondering what you should write. I’ve got good news. I’M GOING TO TELL YOU! There isn’t a person on this planet who knows what screenplays Hollywood’s buying better than me (it’s the new year, let me hyperbolize). But seriously, we know that Hollywood currently hates spec scripts. And who can blame them. The last three major spec sales (Collateral Beauty, Allied, Passengers), all underperformed this winter. If they had it their way, everything would be IP from this point forward.

But fear not! There are still plenty of script options a screenwriter can write and still sell. That’s what today’s article is about. I’m going to give you ten PROVEN genres that Hollywood will eagerly snatch up as long as you deliver the goods. Are you ready? Start taking notes. Cause this article is going to change your life!

Biopic – The biopic is still chugging along. Why? Simple. A-list actors are no longer needed to drive major tentpoles. Those A-list actors had to go somewhere to stay relevant. Enter the biopic, where they get to play famous historical figures and earn Oscar nominations. Who wouldn’t sign up for that? However, keep in mind that this genre is getting crowded. Everyone’s writing in it. So make sure you’re not phoning it in (i.e. don’t research your subject on Wikipedia). Find a unique and interesting way to tell the story so your biopic stands out from the rest!

True Story – This is the fastest growing spec genre out there and, in a way, the biopic’s little brother. But unlike a biopic, the subject doesn’t have to be super-famous. They need only have been involved in a fascinating true-life story. I’ve always wanted to write the real life story of Roswell (not the tin-foil hat version, but one based on facts and real interviews from those involved). Find that true story that you find fascinating, like yesterday’s David Steeves survival tale. Or the infamous “Astronaut Diaper” story chronicled in Pale Blue Dot. Or even the freaky tale about the woman who went crazy at that Los Angeles hotel and ended up in the water supply. So many great real life stories to choose from.

Female-Driven Anything – Ghostbusters didn’t deter Hollywood from their infatuation with female-driven fare. They want more female led films, both fiction and non-fiction alike. Action and comedy are the sweet spots because audiences pay the most for ass-kicking and laughs. But as long as you’ve got a great idea with a female in the lead, you should be good.

Budget-Conscious Action Spec with Franchise Potential – Action will never die. It’s the only genre that will play well in every single country it’s shown. The tough thing about action is finding an idea that hasn’t already been done before. John Wick’s secret society hitman world was cool. And while I didn’t like The Accountant, its non-traditional main character made for a unique take on the action genre. Also, you want to think franchise. So don’t make the film too self-contained. It should hint at bigger things to come. Also, don’t blow the roof off the doors with your budget. In order for something non-IP to get made, the first film will need to come in at a price, probably between 60-70 million. If the movie does well, the franchise begins, baby.

Horror Spec – The horror space is THE most competitive genre of them all. Horror has the biggest cost-to-potential-profit margin of any genre out there. A 2 million dollar film can pull in 100 million at the box office. No other genre even comes close to that kind of upside. For that reason, don’t give me another movie about zombies in the forest. You have to be unique. You have to find another way in. A good comp is A Cure for Wellness, the new horror film coming out from Gore Verbinski. It doesn’t quite feel like something we’ve seen in the horror genre before.

A spec in the superhero universe that isn’t about traditional superheroes – Newsflash. Hollywood is obsessed with superheroes. However, you don’t have access to the millions of dollars required to purchase famous superhero characters and write about them. Therefore, get creative. Find a superhero idea that’s not quite about superheroes. For example, a team of famous superheroes suddenly lose their powers and must integrate into society as normal people for the first time in their lives (think a famous boy band after the glitz and glamour is all gone). Something like that, where you’re coming at the genre from a different angle. Hmm, that’s actually a good idea. Maybe I’ll write that.

A “Voice” Spec – If people always tell you that you have a unique perspective of the world, or you see things in a different way, consider writing a script that highlights your voice. The great thing about writing a “voice” script is that you don’t have to write about anything exceptional. Your VOICE is the exceptional part. You can write about a guy with a shitty job, as long as you give us a perspective on guys with shitty jobs that we haven’t seen before. One note: Vocie-y writers go off the reservation too often. Voice is good, but you still need a story that goes somewhere, or explores something universal. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind was a very voice-y script, but it was exploring something universal – our fear of getting hurt, our struggles to overcome our past. It wasn’t the dreaded “rambling voice,” which is where bad voice scripts go badder.

Swords and Sandals Spec – I’m always looking for that genre that’s traditionally done well at the box office but hasn’t had a hit in awhile. The last swords and sandals hit was the Pirates movies. But the Pirates movies have become stale. I think a good swords and sandals script has the potential to explode onto the market. One note: HUMOR. I believe the reason Pirates did well while the recent Gods of Egypt did not was how well-done the humor was in Pirates. In fact, I was watching The Princess Bride the other day and thinking, “Someone needs to write the next Princess Bride!” A self-referential comedic swords and sandals movie? Start counting your money now.

A Forward-Thinking Spec – Our world is changing faster than it ever has before. Instagram, Uber, Fake News, Fake lives on Facebook, self-driving cars, our every movement being tracked, phone addiction, life disconnection — All of these things are dramatic elements that could be integrated into your next screenplay. Because if you’re writing a movie that could’ve been written in 1996, or even 2006, it’s probably not going to feel fresh. A comedy about what would happen to millennials if the internet went down for a week. I’d go see that. Shit, that’s another good idea. Why am I giving these away?

That Weird Idea You Have – This is actually the best time to write something weird, since the entire spec market has become so homogenized. There’s never been a time in history where more of the same hasn’t been peddled to film audiences. Your weird idea is going to stand out so much more than it did in the past. The weird idea spec may not sell, but like a good voice spec, it can catapult you into the industry and get you tons of work.

Genre: Drama – True Story

Premise: During the Cold War, a crashed pilot becomes a hero after surviving 54 days in the wild, only to see his heroism disintegrate when details of his survival come into question.

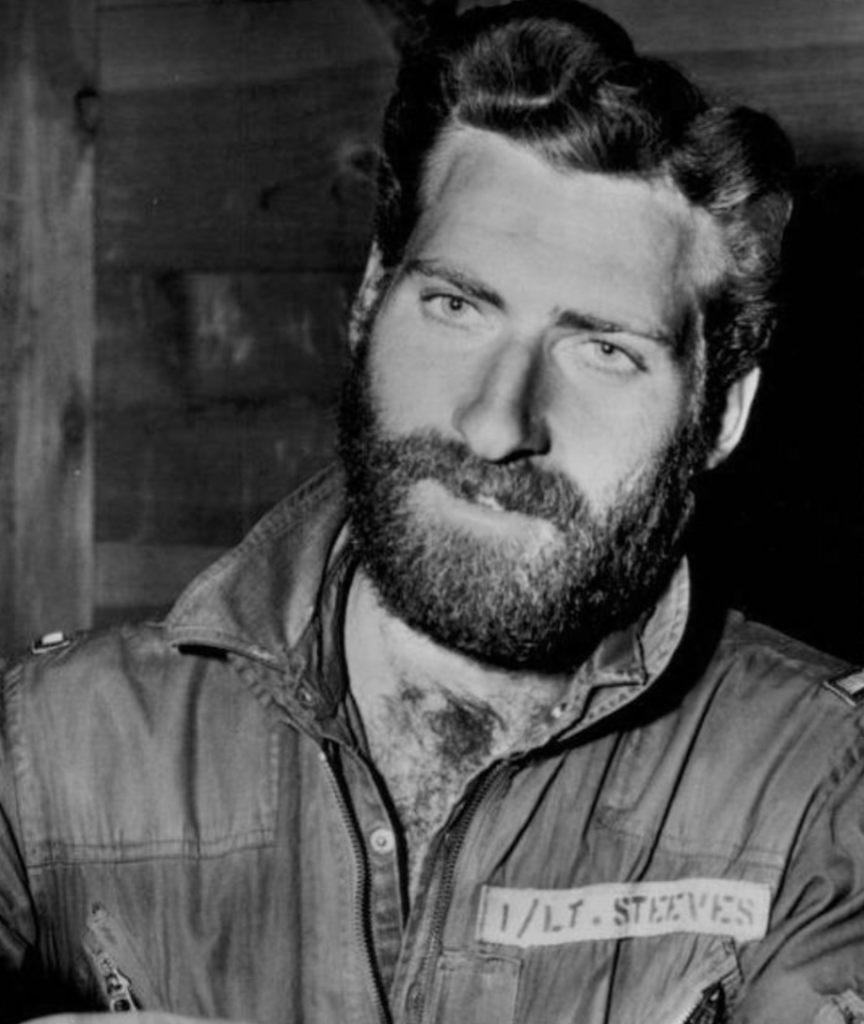

About: I’m not going to make a definitive statement here, because I don’t know why Parter and Hillborn wrote this script. But if you put a gun to my head, I’d guess that they saw a picture of the story’s subject, David Steeves, realized he looked EXACTLY like Bradley Cooper, and wrote the script figuring it’d be a formality to get Cooper to sign on. Also, part of their genius was to PLACE THE PICTURE I INCLUDED BELOW AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SCREENPLAY. Think they didn’t know that producers would alert Cooper to the resemblance? This script finished in the middle of the pack on the most recent Black List.

Writers: Evan Parter and Paul Hilborn

Details: 130 pages

If you want to know what Hollywood’s buying, all you have to do is look through 2016’s Black List. The list is dominated by four categories…

Biopic.

True Story.

Female-driven action movie.

Female-driven comedy movie.

I’ve already made my opinion known on this. I’d prefer something original, something different. But if you’re someone who surfs with the trends, you’ll want to write in one of these genres.

Today’s script goes with choice number 2 and follows David Steeves, a Cold War Air Force pilot who emerged from the Sierra Mountains after being presumed dead for 54 days, after his jet had crashed.

If you thought Sully was a big deal, Steeves became an instant national sensation. He had the looks, the beautiful eyes, and that glorious beard. That beard alone sold headlines.

So big was Steeves that the Post paid him 10 grand for the exclusive rights to his survival story. The man assigned to the story was Clay Blair Jr, a 30-something journalist new at the Post with plans to shake the newspaper up.

As Blair interviews Steeves about his story, we intermittently flash back to Steeves’ perilous journey, most of which hinged on him finding a shack in the middle of nowhere. He used that as his home base, and would’ve starved to death had he not come across it.

At first enamored with Steeves, Blair begins to see little gaps in his story, particularly regarding Steeves’ crashed jet, which was never found. A narrative begins forming that Steeves may have hoaxed his survival story to cover up that he’d sold his jet to the Russians.

The problem with Steeves is that he was far from the model citizen. A drunk and a womanizer, Steeves would routinely cheat on his wife. This painted a picture of a man who built a life around deceit. If he could deceive his wife, why couldn’t he deceive the nation? When Blair decides to cancel the story, the nation swarms in, wanting to know why, and that’s when Steeve’s story, and his life, really begin to fall apart.

If you forced me to pick between the above four trends, I would pick ‘true story’ without hesitation. It allows you to cherry pick a superb story. But more importantly, if you can find a killer true story, it does the work for you. You don’t have to be a great screenwriter to pull it off. You just need to know what you’re doing and let the story write itself.

Think about it. One of the hardest things about writing fiction is when you get to page 50 (or 60 or 70) and run out of story. With a true story, you know what happens ahead of time and can structure the script out accordingly.

A biopic, by comparison, requires a ton of skill, since you have to shape an entire person’s life into two hours, not to mention make it dramatic and entertaining. Since there’s a lot of dead time in a person’s life, it gets tricky figuring out what to include and what to ditch.

This is why Kings Canyon works. A man becomes a hero based on a lie. And both the “hoax” and the “lie” are highly dramatically compelling. That’s what you’re looking for when you’re trying to find a true story. Are its key plot points HIGHLY DRAMATICALLY COMPELLING?

For shits and giggles, let’s pretend this was a real life story about a man who stole $1000 from his employer, then was brought into his boss’s office where he was told they’d caught him. He then had to prove his innocence. Is there drama in that scenario? Sure. Is it HIGH DRAMA? No. The stakes are tiny. With Kings Canyon, you have a man who potentially sold military secrets to our country’s biggest enemy during a time when we all thought a nuclear war with that country was imminent. That’s high drama.

But there are some issues. Because we can’t tell the audience what Steeves is hiding for most of the movie, we’re only ever subjected to his surface. When he’s with his wife, we’re never privy to what he’s thinking. Even in the flashbacks, we only see Steeves’ struggle to survive. We don’t get inside of him.

I would argue that there are 4 other characters we know better than Steeves through the first half of the screenplay. Parter and Hillborn seem to realize this was a problem, and therefore shift the main character role over to Blair. He’s the one with the goal anyway (find the real story), so it makes sense.

But if you’re writing a movie about what happened to someone, are we ever going to feel satisfied if we don’t get to know that someone? Once the “lie” is exposed, Steeves is finally able to come alive as he fights for his dignity. But it’s a long wait, and he’s only active for the final act.

Regardless of that, the script works because the entire thing is a ticking time bomb slash mystery. We know the truth is going to come out sooner or later, and we also want to know what that truth is. As long as you have a compelling question driving your narrative, it’s impossible for your reader to stop reading.

By far the script’s most powerful engine is that of its flashback structure. As the story unfolds, we’re told more and more often that Steeves is a fraud who perpetuated a hoax. However, every time we flash back, even deep into the screenplay, Steeves is in the wild, clearly injured, and clearly trying to survive.

That contrast only deepens our curiosity. If there’s a hoax, what is it? Because it isn’t that Steeves made up his tale of survival.

I also thought the ending was great. There are a couple of late story twists that make you feel like the journey was worth it. So many times you read scripts with these inevitable endings. Like Rogue One. We know the ending at the beginning, so there’s only so much satisfaction we can gain once we get there. Kings Canyon not only throws you for a couple of loops, but it makes you think long and hard about the media-obsessed culture we live in.

I have a feeling they’re going to have a hard time getting Cooper or an actor of his caliber to play Steeves, only because the actor doesn’t have much acting to do for the majority of the story besides look happy. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe they’ll be drawn to the survival scenes so much that they’re willing to do nothing for the first 3/4 of the present-day narrative. We’ll see. Whatever the case, this screenplay rocked.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I don’t know if this is a lesson so much as an observation. But I loved how the flashback structure didn’t match up with the present-day narrative (the present is saying he’s a hoaxer, but the flashbacks are saying he’s telling the truth). That alone kept me fascinated throughout Kings Canyon. So maybe our lesson is “contrast between flashbacks and present day creates curiosity?” What I do know is that when your flashbacks tell us exactly what we’re being told in the present, they’re boring as shit. So definitely don’t write your flashbacks that way!

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: After an alien ship crash lands in the Mojave Desert, a small group is sent in to inspect it, only to find themselves slowly losing their minds.

About: This script sold a couple of years ago and then disappeared. However, it recently underwent a rewrite assignment. Whenever a script undergoes a rewrite, that’s a good sign. If producers are paying money to have a writer write a new draft, it means they’re trying to push the script to the next stage (find attachments). If a script was sold four years ago and nobody’s working on it, that project is basically dead. The draft I’m reviewing today is the original Terrestrial spec that sold.

Writer: Peter Gaffney

Details: 101 pages – 1/27/14 draft

It’s the new year. And the new year always gets you thinking.

Reminiscing about the past. Wondering about the future. It also forces you to evaluate what you do. I just came across a Jerry Maguire interview on Deadline that began with this line: “Before we get back to the cynical world we live in, how about a sentimental reminiscence with Cameron Crowe…”

In a vacuum, it’s a hollow line. But in context, it sums up the industry I operate in. Movie sites live to emphasize what’s wrong. What’s wrong with Passengers? What’s wrong with Sony? What’s wrong with the indie box office? What’s wrong with the spec market?

All of these are worthy questions. But they drive forth a negative culture that serves to depress the hell out of anyone involved in the industry, as well as anyone trying to get into it. Not even the successes get celebrated anymore. Rogue One will become the biggest box office movie of the year. But go to any movie site (including my own) and all you’ll find is people complaining about it.

I suffer from this disease. I can go two weeks without reviewing something positively. And it kills me. I don’t like giving negative reviews. I wish every script was great, something to celebrate, something we could learn from and be inspired by.

But my bar gets higher every day. Every time I read a script, I become more numb to that type of story. Take today’s script. It’s an “aliens come to earth” script. One of my favorite genres. But also a well-tread one. So when I read Terrestrial, it was, “I’ve seen this before, I’ve read this act before, I’ve seen these characters before…”

It’s hard to impress me. And I’m not going to say, “Wow, this was great!” when it isn’t just to stay positive.

So it puts me in this awkward position where I desperately want to celebrate screenplays but there aren’t enough people writing screenplays that are worthy of celebration.

So I call out to all of you in 2017, amateurs and professionals alike: write a script where you take a chance. That weird idea you have in the bottom of your drawer that you love but you’re terrified of because you think, “It’s too weird. Nobody’s going to go for it.” And you know what? You might be right.

But it could also be amazing. Because what we need now is a revolution – the same way those gunslinger writers and directors changed the game in the 70s and the 90s. And it starts with the writing. It starts WITH YOU. So write your safe script since you have to make a living. Your biopic or true story. But also write your weird “I’m scared shitless of this script” script. Here are a few scripts to inspire you…

Okay, now that I’ve melted your minds with that glob of advice, let’s get into today’s script…

Former Professor David Cantor is living in a Motel 6, wondering where his next job is going to come from. The man hasn’t had the best life, losing his wife and little girl in a fire.

No sooner does Cantor wake up from one of his nightly nightmares than he’s greeted by an army trooper who tells him to pack his bags. Cantor is whisked away and introduced to former Army Ranger Tom Kostovo, who hates his life just as much as Cantor.

Kostovo flies Cantor to the Mojave Desert where Cantor sees their destination – a giant crashed alien space ship.

After meeting with a small team there, we learn that Cantor once made contact with a tribe in the jungle that had never interacted with the outside world before. The army believes that skill will come in handy as they try and communicate with these aliens.

Kostovo and Cantor are joined by a beautiful young woman named Ellen Johannes, a theoretical biologist, and head into the ship to check it out. There, they find that the crew has been killed. But maybe not by the crash.

Everywhere they look, vines cover the ship’s insides, some even growing out of the alien corpses. When Kostovo and Cantor reach the center of the ship, they find the town Cantor grew up in. That’s right: Cantor’s town is in the middle of an alien space ship.

Cantor heads to his old address and finds that not only is his house still there, but so are his wife and daughter! Kostovo also finds the army unit he watched blow up back in Iraq. Meanwhile, Johannes is the only one who’s not hallucinating.

She eventually realizes what’s happening. These vine-plants cause people to go crazy and use that insanity to help them spread to the next host. And they want that next host to be earth!

If Johannes doesn’t convince Kostovo and Cantor that they’re being fucked with by alien vines, there’s a good chance our planet will be plant food by the end of the week.

This script had an uphill battle with me. A plot point I’ve never been fond of is the “ship causes hallucinations” storyline. Dating back to Sphere, it feels like the choice you go with when you don’t have enough story to tell after your characters enter the ship.

At the same time, I see why it’s appealing. It’s an easy way to explore character. You build the hallucinations around a problem from each characters’ past and we stick around to see if they’re able to resolve them. Cantor needs to get over the loss of his wife and daughter, therefore the hallucinations are about his wife and his daughter.

And yet there’s something about it in this setting that bothers me. When I go to an alien invasion movie, I don’t go to see a dude hanging out with his dead wife and daughter. I go to be pulled into the mystery of who the aliens are, where they came from, and why they’re here. That’s why I liked Arrival’s script so much.

Also, if you’re going to explore the internal, you have to do one of two things. Either it has to be a realistic portrayal of an internal problem, or it needs to be something unique we haven’t seen before. The two issues from these characters’ pasts – Cantor with his family dying in a fire and Kostovo with his unit dying in Iraq – felt “written,” the thing you feel like you’re supposed to write rather than thing that should be written.

With that said, the script gets better as it goes on. While at first I found the plants to be boring, their emergence as the true threat took the story into some interesting territory. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough to make up for the aversion I have to this plot scenario.

We’ll have to see if the rewrites solve that problem. I’m sure the success of Arrival has made this project a priority to someone!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There are two kinds of writers. There’s the writer who loves crowd-pleasing Hollywood movies. And there’s the anti-establishment writer who writes offbeat stuff. Regardless of which type of writer you are, you should be writing BOTH types of scripts. You should be working on your mainstream script and you should be working on your offbeat script (writing back and forth between the two, if possible). Writing outside of your comfort zone makes you a better writer inside your comfort zone.

Hey guys. We’re going to jump back into regular posting next week. For right now though, I have a special treat for you. A NEW Scriptshadow Newsletter!! If it’s not in your Inbox, make sure to check your SPAM or PROMOTIONS folders and you should find it. I review an awesome screenplay by one of the hottest screenwriters in the business. I give you the matchups for our Scriptshadow Tournament semifinalists. And, as always, there are lots of screenwriting tips and links, as well as Scriptshadow consultation deals, inside.

If you don’t see the newsletter in any of your folders, e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “NO NEWSLETTER” and I’ll send it to you personally. If you want to be added to the newsletter, e-mail me at the same address with the subject line “NEWSLETTER” and I’ll send. If you’ve been on the list and still never receive newsletters, I recommend signing up with another e-mail address.

ENJOY and I’ll see you in the NEW YEAR!