Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: After an alien ship crash lands in the Mojave Desert, a small group is sent in to inspect it, only to find themselves slowly losing their minds.

About: This script sold a couple of years ago and then disappeared. However, it recently underwent a rewrite assignment. Whenever a script undergoes a rewrite, that’s a good sign. If producers are paying money to have a writer write a new draft, it means they’re trying to push the script to the next stage (find attachments). If a script was sold four years ago and nobody’s working on it, that project is basically dead. The draft I’m reviewing today is the original Terrestrial spec that sold.

Writer: Peter Gaffney

Details: 101 pages – 1/27/14 draft

It’s the new year. And the new year always gets you thinking.

Reminiscing about the past. Wondering about the future. It also forces you to evaluate what you do. I just came across a Jerry Maguire interview on Deadline that began with this line: “Before we get back to the cynical world we live in, how about a sentimental reminiscence with Cameron Crowe…”

In a vacuum, it’s a hollow line. But in context, it sums up the industry I operate in. Movie sites live to emphasize what’s wrong. What’s wrong with Passengers? What’s wrong with Sony? What’s wrong with the indie box office? What’s wrong with the spec market?

All of these are worthy questions. But they drive forth a negative culture that serves to depress the hell out of anyone involved in the industry, as well as anyone trying to get into it. Not even the successes get celebrated anymore. Rogue One will become the biggest box office movie of the year. But go to any movie site (including my own) and all you’ll find is people complaining about it.

I suffer from this disease. I can go two weeks without reviewing something positively. And it kills me. I don’t like giving negative reviews. I wish every script was great, something to celebrate, something we could learn from and be inspired by.

But my bar gets higher every day. Every time I read a script, I become more numb to that type of story. Take today’s script. It’s an “aliens come to earth” script. One of my favorite genres. But also a well-tread one. So when I read Terrestrial, it was, “I’ve seen this before, I’ve read this act before, I’ve seen these characters before…”

It’s hard to impress me. And I’m not going to say, “Wow, this was great!” when it isn’t just to stay positive.

So it puts me in this awkward position where I desperately want to celebrate screenplays but there aren’t enough people writing screenplays that are worthy of celebration.

So I call out to all of you in 2017, amateurs and professionals alike: write a script where you take a chance. That weird idea you have in the bottom of your drawer that you love but you’re terrified of because you think, “It’s too weird. Nobody’s going to go for it.” And you know what? You might be right.

But it could also be amazing. Because what we need now is a revolution – the same way those gunslinger writers and directors changed the game in the 70s and the 90s. And it starts with the writing. It starts WITH YOU. So write your safe script since you have to make a living. Your biopic or true story. But also write your weird “I’m scared shitless of this script” script. Here are a few scripts to inspire you…

Okay, now that I’ve melted your minds with that glob of advice, let’s get into today’s script…

Former Professor David Cantor is living in a Motel 6, wondering where his next job is going to come from. The man hasn’t had the best life, losing his wife and little girl in a fire.

No sooner does Cantor wake up from one of his nightly nightmares than he’s greeted by an army trooper who tells him to pack his bags. Cantor is whisked away and introduced to former Army Ranger Tom Kostovo, who hates his life just as much as Cantor.

Kostovo flies Cantor to the Mojave Desert where Cantor sees their destination – a giant crashed alien space ship.

After meeting with a small team there, we learn that Cantor once made contact with a tribe in the jungle that had never interacted with the outside world before. The army believes that skill will come in handy as they try and communicate with these aliens.

Kostovo and Cantor are joined by a beautiful young woman named Ellen Johannes, a theoretical biologist, and head into the ship to check it out. There, they find that the crew has been killed. But maybe not by the crash.

Everywhere they look, vines cover the ship’s insides, some even growing out of the alien corpses. When Kostovo and Cantor reach the center of the ship, they find the town Cantor grew up in. That’s right: Cantor’s town is in the middle of an alien space ship.

Cantor heads to his old address and finds that not only is his house still there, but so are his wife and daughter! Kostovo also finds the army unit he watched blow up back in Iraq. Meanwhile, Johannes is the only one who’s not hallucinating.

She eventually realizes what’s happening. These vine-plants cause people to go crazy and use that insanity to help them spread to the next host. And they want that next host to be earth!

If Johannes doesn’t convince Kostovo and Cantor that they’re being fucked with by alien vines, there’s a good chance our planet will be plant food by the end of the week.

This script had an uphill battle with me. A plot point I’ve never been fond of is the “ship causes hallucinations” storyline. Dating back to Sphere, it feels like the choice you go with when you don’t have enough story to tell after your characters enter the ship.

At the same time, I see why it’s appealing. It’s an easy way to explore character. You build the hallucinations around a problem from each characters’ past and we stick around to see if they’re able to resolve them. Cantor needs to get over the loss of his wife and daughter, therefore the hallucinations are about his wife and his daughter.

And yet there’s something about it in this setting that bothers me. When I go to an alien invasion movie, I don’t go to see a dude hanging out with his dead wife and daughter. I go to be pulled into the mystery of who the aliens are, where they came from, and why they’re here. That’s why I liked Arrival’s script so much.

Also, if you’re going to explore the internal, you have to do one of two things. Either it has to be a realistic portrayal of an internal problem, or it needs to be something unique we haven’t seen before. The two issues from these characters’ pasts – Cantor with his family dying in a fire and Kostovo with his unit dying in Iraq – felt “written,” the thing you feel like you’re supposed to write rather than thing that should be written.

With that said, the script gets better as it goes on. While at first I found the plants to be boring, their emergence as the true threat took the story into some interesting territory. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough to make up for the aversion I have to this plot scenario.

We’ll have to see if the rewrites solve that problem. I’m sure the success of Arrival has made this project a priority to someone!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There are two kinds of writers. There’s the writer who loves crowd-pleasing Hollywood movies. And there’s the anti-establishment writer who writes offbeat stuff. Regardless of which type of writer you are, you should be writing BOTH types of scripts. You should be working on your mainstream script and you should be working on your offbeat script (writing back and forth between the two, if possible). Writing outside of your comfort zone makes you a better writer inside your comfort zone.

Hey guys. We’re going to jump back into regular posting next week. For right now though, I have a special treat for you. A NEW Scriptshadow Newsletter!! If it’s not in your Inbox, make sure to check your SPAM or PROMOTIONS folders and you should find it. I review an awesome screenplay by one of the hottest screenwriters in the business. I give you the matchups for our Scriptshadow Tournament semifinalists. And, as always, there are lots of screenwriting tips and links, as well as Scriptshadow consultation deals, inside.

If you don’t see the newsletter in any of your folders, e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “NO NEWSLETTER” and I’ll send it to you personally. If you want to be added to the newsletter, e-mail me at the same address with the subject line “NEWSLETTER” and I’ll send. If you’ve been on the list and still never receive newsletters, I recommend signing up with another e-mail address.

ENJOY and I’ll see you in the NEW YEAR!

It’s here. It’s now. The ten worst films I saw and the ten best. It should be noted that I haven’t seen La La Land, Manchester by the Sea, Collateral Beauty, Passengers, Fences, or Billy Lynn. I’m pretty sure Billy Lynn and Collateral Beauty (going off of what everyone’s saying) would’ve made my “Worst” list. But alas, I don’t have the endurance anymore to go to movies I know I’m going to hate. So, here’s what’s left…

WORST FILMS

10) Ghostbusters – The cinematic embodiment of the social justice warrior crusade, telling us that we have to like what they, the world, has decided is best for us. The result was a movie that everyone watched and went, “Wait, why do Ghostbusters have to be women now? Why can’t they just be men and women?” Because men in 2016 are bad, that’s why.

9) Batman vs. Superman – So pretentious in its writing and directing that it gave you aches in places you didn’t now you could ache. After the 17th flashback to either Batman or Superman’s past, I wondered if the movie even cared about the present. How a movie with the two most popular superhero characters of all time could be so boring is a question aliens will debate one day when they take over our planet in 2512.

8) The Accountant – I didn’t see a more nonsensical movie all year. He’s OCD. He’s a contract killer. No, wait, he’s an accountant. No, he’s a consultant for companies. No, his dad taught him kung-fu. What’s the plot again? The government needs to find him RIGHT AWAY because he’s living somewhere and not bothering anybody? And he launders money.

7) High-Rise – A beautifully shot film without even 10 minutes spent on a screenplay, this film felt like Ben Wheatley stumbled onto the set and started making up things as he went along. Get a screenwriter, Ben. You’re a stud filmmaker but you can’t do it on your own.

6) Money Monster – An idea plucked out of the early 2000s given the treatment of 1990s film, attempting to rip off the chaos of the 1970s. After it was all said and done, it became a 2016 disaster, a bunch of old people who’ve lost touch with what audiences want. I’m all for adult fare, but you need to know what adults actually want.

5) The Witch – Holy Moses this was the most overrated piece of garbage of the year. I thought I was about to watch something amazing. Instead I witnessed a pretentious period piece with a bunch of well-costumed actors stumbling around a photograph-friendly farm. Another director who’s never learned how to tell a story. Wonderful.

4) Midnight Special – One thing that drives me batty is when reviewers give a bad film a good grade cause doing otherwise would fuck with the narrative. Jeff Nichols is supposed to be this up-and-coming filmmaker and this was supposed to be his break into the mainstream, his “early Steven Spielberg” film. Instead, it was a wandering mess that never committed to anything concrete, choosing instead to imply a whole lot of nothing, leaving us wondering what the point of the movie was when it was over. It’s okay to write screenplays that make sense. And it’s okay to say a movie sucked even when it doesn’t fit the narrative.

3) A Hologram For a King – This movie was the most bizarre thing I saw all year. It felt like something directed by Siri. Yes, I’m talking about the Artificially Intelligent concierge on your phone. Tom Hanks technically gave a performance, though I have a strong suspicion that he Skyped in his scenes standing in front of a green screen, which were then digital inserted into the film. If that doesn’t sell you, maybe the plot where nothing happens for 120 minutes will win you over.

2) Eddie the Eagle – Easily the worst performance of the year. I want you to go to the nearest mirror and make the goofiest smile-face you can think of. That was the actor’s, in this movie, entire performance. The writer also forgot to leave the 80s, as this screenplay seems to have been written immediately after a binge-watch of every 80s comedy ever made.

1) Sully – Was this the worst movie of the year? Probably not. Was it the most pointless movie of the year? Definitely. Sully and Billy Lynn (of which I read the book) are an example of what happens when you try to make a movie without a single dramatic beat. Drama is the essence of entertainment, something the makers of this film either don’t know or, worse, ignored.

BEST FILMS

10) Central Intelligence – Before you castrate me for liking this film, a film I’m sure you haven’t seen, let me add some perspective to the conversation. I don’t like Kevin Hart at all. I detest nearly every film he’s in. That Ride Along flick is garbage. Central Intelligence, however, not only gives us the best chemistry between two actors in any movie this year, but it’s a surprisingly good screenplay. Nothing flashy. Stays close to all the beats you’re supposed to hit. Yet it manages to stay ahead of the reader/viewer. Biggest surprise all year as I expected this to suck.

9) Tony Robbins: I Am Not Your Guru – I promise you there isn’t a film you’ll see this year that will make you squirm more than this one. It’s on Netflix and all I ask is that you watch the opening scene. I promise you won’t be able to look away. You’ll ask, out loud, “Does this really happen?” It does. Welcome to the cult of Tony Robbins.

8) Kubo and the Two Strings – This movie isn’t perfect. Before seeing it, I heard people marveling at how a “simple story could be so good.” But Kubo isn’t simple at all. Actually, it has some of the more complex and hard-to-follow world building I’ve encountered this year. Despite that, it’s a beautiful film to watch and listen to, and comes together in such a satisfying way in the end.

7) Zootopia – There wasn’t a movie in 2016 that made you feel happier to be alive than this one. That damn rabbit is so freaking cute.

6) Deadpool – The superhero genre needed to be disrupted. Deadpool charged towards the wall Hollywood tried to put up in front of it, broke through, and gave us the biggest box office surprise of 2016. It also reinforced the notion that nothing ever gets made by accident in this town. There has to be at least one person who will stop at nothing to get their movie made. Deadpool had four of those people and we’re the beneficiaries of their drive.

5) Weiner – I know, I know. Another documentary, Carson? Really? Just watch this film. You’ve never met anyone who can’t get out of their own way the way Anthony Weiner can’t get out of his own way. What a freaking weirdo. What’s so strange is that when he’s out in public speaking about issues and policies, he’s captivating. Then he gets home and all bets are off. The x-factor about this movie is the weird way in which it will later influence the 2016 presidential election.

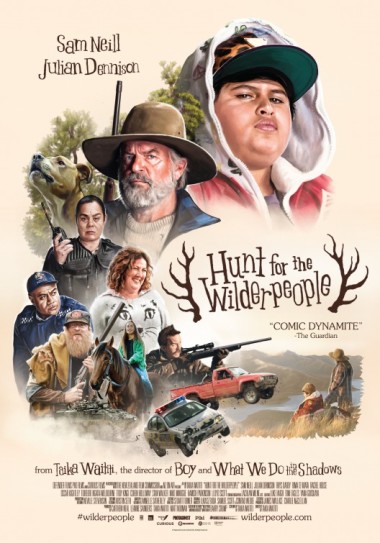

4) Hunt for the Wilderpeople – This movie makes me want to move to New Zealand. I loved the main character. I loved the relationship between the main character and the stepfather. I loved how you had no idea what was going to happen next. This movie makes you feel good about life in a different way than say, Zootopia, but does the job nonetheless.

3) Eye in the Sky – I never thought I’d like a movie about drones so much. But let me put this not so delicately. This is the movie The Hurt Locker could’ve been if it had a screenplay. They actually thought this thing through, and, as a result, we get the most tension-filled movie of the year.

2) Swiss Army Man – The best movie score of the year accompanies the trippiest movie of the year. This movie is not for everyone, but it’s the only movie that I saw all year that took REAL ARTISTIC CHANCES and those chances actually paid off. It’s weird, it’s unsettling, it’s funny, it’s awkward, but most of all, it’s unlike anything you’ve ever seen.

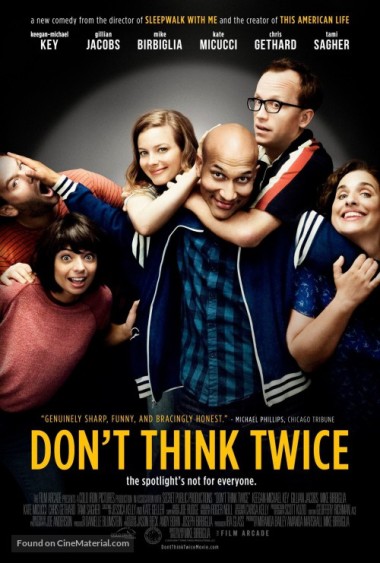

1) Don’t Think Twice – This is the only movie I saw all year that genuinely affected me on an emotional level. Sure, part of that is because it’s about the “artist’s journey” which is so relatable to me. But the character development is better than any other screenplay this year by miles. And like any good movie, it keeps getting better as it goes on. If you’re an artist, you will want to see this movie. It’s perfect.

Sorry about the lack of posts. I was at LAX all night yesterday trying to get back to the Midwest. I didn’t make it but it looks like a Christmas miracle might get me out tonight. Before we move on to today’s article, I want to beg every traveler out there to please never fly American Airlines for the rest of your lives. Not only is it a terrible airline as far as comfort and customer service, but they have to be the most clueless airline company on the planet.

After being bumped 3 times last night to later and later flights, my last flight changed gates ELEVEN TIMES. That is not a printing error nor is it an exaggeration. In addition to this, I saw three women break down, fall to the floor, and start crying, due to how much they’d been dicked around all night, and one man lead a 30 person revolt against the gate attendant. It was insane.

After we’d changed gates for the 10th time, American Airlines kept saying we couldn’t board because the plane outside was broken, and they needed to tow it out before they could bring in “our plane.” We waited an hour for this towing to happen. Finally, when they moved us to our 11th and final gate, which did not have a plane in it, many astute passengers pointed out that since they no longer needed to tow a plane away, they could bring “our plane” up and start boarding. American Airlines, clearly caught in a lie, quickly moved to a new excuse about air traffic being broken or something.

I know the holidays are crazy for air travel but I’m not basing my critique here on just this experience. Every time I have flown American Airlines, it has been terrible. I only flew them this time because I had to. But I will never fly them again after this. It was the last straw.

Now, on to funner topics!

Because I don’t have time to write an in-depth article or review, I thought I’d share with you some brief thoughts on a screenwriting concept that’s always frustrated me: THEME

Theme has always been a tricky concept. To this day, I’m yet to meet someone who’s given me a definition for theme that doesn’t sound bullshitty (this is why theme posts get debated so vigorously – since there is no definition, everyone’s interpretation is different). But the other day I stumbled upon a Youtube video covering academia and had a mini-revelation. As I retroactively tested that revelation, I realized how much sense it made.

The idea is this. “Theme” comes in two flavors – simple and complex. BOTH can work effectively. You can use the simple version of theme and still write a good movie. In fact, I’d argue that the simple version gives you a better chance at writing a good movie. However, the complex version gives you a chance at writing a GREAT movie.

But before we get into that, let’s remind ourselves why we’d want a theme in the first place. A theme is there to keep your story focused. Whenever you lose your way, like a lighthouse, the theme is there to steer you back on course. Without a theme, your script seems scattered, confused, and unsure of what it’s trying to say.

If you were to grade this article on theme, for example, it would fail. I started out talking about how shitty American Airlines was before moving onto a screenwriting article. That’s thematically inconsistent, which is why this article feels messy. You could argue that because I just referenced my opening to prove a point about theme, that the theme for this article is intact, but that’s a debate for another time.

On to “simple theme.” The simple version of theme is the act of wrapping everything around a single idea. That idea can be anything! Take the Star Wars movies. A common theme I’ve heard thrown around for them is “Good vs. Evil.” As long as you play out the struggle of good vs. evil, the movie’s going to feel consistent and whole. However, if a storyline popped up in Star Wars about a character who was obsessed with money and needed to have all the money in the universe, you’d be like, “Uh, what the hell does this have to do with Star Wars?”

Or take Zootopia. The theme there is that we can be anything we want if we put our minds to it. It’s a simple easy to follow formula that gives your movie a point. And since Star Wars and Zootopia are both awesome movies, we know this type of theme works.

Now let’s move to the complex version of theme. To achieve this, we’ll be transforming the word itself. “Theme” will now become “Thesis.” The idea with a thesis is to create a question or theory that has to be proven or debated over the course of the story. Whereas bigger budget Hollywood fare will lean on theme to power its core, character pieces rely more on a thesis. And the best way to understand the power of a thesis is to compare two similar character pieces, one that used a theme, the other that used a thesis.

The first is Sully. Sully was boring as shit. Why was it boring as shit? Because the theme was boring as shit. What was that theme: Heroism. That’s it! A man being a hero. Now yes, that kept the story consistent throughout its running time. We were never confused about what Sully was about. But because this was a character piece, it needed a thesis, something that forced us to think a little more.

Bring in Flight. Flight based its screenplay on a thesis, that thesis being: “Can a bad person still be a hero?” Denzel Washington’s captain character put 250 peoples’ lives at risk by drinking all night and snorting up coke before he piloted that flight. But he still ended up pulling off a radical maneuver that saved most of the passengers’ lives. Notice how, by using a thesis, the story becomes a lot more complex. We’re not sure what we think of Whip. Yeah, he saved all those people, but he shouldn’t have gotten on that plane fucked up in the first place.

In both cases, we have something to center the story on. But in one, that something merely represents what’s going on, whereas in the other, it forces us to continually ask a question. Can bad people be heroes?

Hey wait a minute. My last two examples were about airplanes. Maybe this article is more theme-centric than I gave it credit for.

I’ll finish by saying this. If you’re just starting out in screenwriting, whether you’re writing a Hollywood movie or a character piece, go with a theme. Even if you’re experienced and you’re writing a Hollywood movie, go with a theme. The only people for whom I’d encourage using a thesis are seasoned screenwriters who are writing character pieces. I say this because I’ve seen beginner screenwriters try and use theses and they always make it too complicated on themselves. By trying to make their stories so intelligent and thematically resonant, they forget to actually make them entertaining. Don’t be one of those guys.

HAPPY HOLIDAYS!!!

Genre: Contained Thriller

Premise: In an apocalyptic future, a teenaged girl raised underground by her robotic mother, begins to question whether everything she’s been taught by Mother is true.

About: This Black List script is written from across the pond. So all you UK writers who think getting your work recognized in Hollywood is impossible, don’t give up! Now Green did work as Colin Farrell’s assistant on Miami Vice, but before you go thinking that’s what got him this opportunity, note that that movie came out all the way back in 2006. I doubt Green called Farrell up after ten years and said, “Hey, remember how I kept your coffee at exactly 71 degrees for the entire production of Miami Vice? Can you read my script?” and Farrell was like, “Sure, and I’ll give it to Spielberg tomorrow.” And, to be honest, I’m not sure Colin Farrell, with his current stature in Hollywood, would be able to do anything for Green anyway. Since Green’s short stint in P.A.’ing, he’s written and produced a couple of short films, but this is his first known screenplay.

Writer: Michael Lloyd Green

Details: 102 pages

A few people have asked me, “Why do readers like contained thrillers?” And while the first answer is that they’re cheap to make and therefore, with a cool concept, have a shot at getting made. They’re also scripts that don’t require the reader to take notes.

This may seem like a strange detail to someone who doesn’t read a lot. But all readers know that there are easy reads and there are difficult reads, and the difficult ones are when you have to take a ton of notes.

Like, recently, I read a love story that took place during World War 1 in Germany. Every page, I had to stop and write down either a new character’s name or a location I was unfamiliar with or some important detail about the war. Those scripts take a lot more out of you.

This script has three characters. Not only that, but the characters’ names are Mother, Daughter, and Drifter. Talk about a script tailor-made for no notes! And, look, I know it sucks. A reader’s job is to read. He should suck it up and work hard even when a script is difficult.

That’s a wonderful way to look at things if you’re an idealist. But the REALITY of the matter is that readers are overworked writers who would rather be working on their own scripts. So you can write as an idealist or write as a realist. It’s up to you.

Does that mean don’t ever write a complicated story? No. Of course not. Some of the best spec scripts ever – The Truman Show, Seven, The Imitation Game, American Beauty – they require focus and, yes, the occasional note-taking.

But this is what makes the screenwriting medium so interesting. If you’re going to go that route, you need to know how to simplify the things that need to be simple, how to always make things clear, and how to make the read easy amongst all that detail. And that takes practice. And it takes KNOWING that you have to do that in the first place, because you’ve written a half-dozen screenplays before this one and got lots of coverage saying, “I don’t know what’s going on here. There’s too much.” It takes time to find that sweet spot of “enough to give your script depth” but not so much that it’s hard to keep up.

So with all that swimming in your noon-day noggin, let’s jump into today’s script, “Mother.”

“Mother” takes place in an underground cavern built to sustain people after a nuclear war. The problem is, there are no people. At least not yet. The entity who runs this facility, a robotic entity known as “Mother,” incubates the first human embryo for a plan, we presume, that will open the door up for earth’s repopulation.

Soon, Daughter is born. Daughter loves her robotic mother at first, but when she grows into her teens, she becomes bored and curious. What’s outside of these dark walls? Mother insists that to go outside means death. The air is contaminated and no human beings have survived.

Except that soon after Daughter finds a secret exit, a bloodied woman appears on the other side. Daughter lets her in, and the woman, “Drifter,” begins to spin a tale that sounds a lot different than the one Daughter’s been told. For starters, there are obviously other human beings alive.

Mother finds out about Drifter, and to both Daughter’s and Drifter’s surprise, decides to help her. But Drifter remains skeptical of Mother, and starts filling Daughter in on what she knows of the outside. For starters, there are machines roaming around, killing people. Could Mother be associated with these machines?

Then again, Daughter repeatedly catches Drifter lying about things herself, leaving her to make the impossible choice. Believe the woman who’s raised her, or the woman who represents everything she’s wanted – to be free and live out in the wild? It’s a decision that, most certainly, will end in death… for one of them.

We’ve been here before, right?

Two people in a contained room. A third enters. Wreaks havoc.

We just saw it with Cloverfield Lane.

It’s a recipe that works.

So what has today’s script added to the setup? Well, we’re in the future. We’ve got a robot. That’s different. And we’ve also got a unique relationship. This isn’t two people who’ve been forced down into a shelter against their will. These “people” have been here for awhile. And the fact that they’re family creates the potential for new plotlines.

The first of those is trust – the trust between a mother and her daughter, and how we’re innately supposed to go along with the way our parents raise us. As children, we don’t know any better. So if our father or mother tells us that killing is good, we believe them. Because what else do we have to go on?

That’s the dilemma at the heart of “Mother.” When does raising a child turn into manipulating a child? And aren’t we all, to a degree, manipulated? We’ve been raised on the morals and ethics of the parents who birthed us. And since our childhood years are the most influential on our make-up, we usually take those beliefs all the way through life.

So that’s the undercurrent of Mother, which is interesting, I guess.

But what about the plot? Does Green solve the biggest issue facing Contained Thriller writers: Coming up with enough story to last an entire movie? Unfortunately not. He does okay. But I felt like I read half-a-dozen scenes of Drifter in the Infirmary complaining about Mother and trying to get Daughter to come with her.

Also, Drifter falls short as a character because she’s so mysterious. Again, when you have a character built on mystery, you can’t explore them below the surface. To do so would be to reveal who they are, which is something the character’s not created for. So Drifter ends up coming off as a repetitive sock puppet – there to repeatedly say, “Mother is lying. I’m not.”

Luckily, the Mother-Daughter relationship is compelling enough to overshadow this weakness. Whenever you can write a character who fills two different extremes, you’re going to get some interesting results. (spoiler) That’s what Mother is. She genuinely loves her child, but she’s also perfectly capable of killing her if she isn’t up to speed with what the repopulation of the human race requires.

So “Mother” was an okay execution of a popular setup that did some nice things. But in the end, it didn’t do enough to excite me or advance the genre. In that sense, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re choosing a script to write, ask yourself, “Is this a note-taking script or a non-note-taking script?” If it’s the former, realize that you’ll be fighting an uphill battle against a reader who will resist the amount of focus required to understand your story. However, if you work hard to make all that extra information clear, and you’ve written an engaging story on top of that, you can travel down this path and survive.