Genre: Spy-Thriller

Premise: As a young CIA spy is about to assassinate her next target, he reveals to her that her agency has been lying to her, and that she’s so much more than she thinks she is.

About: This Black List script will star Zoe Saldana in the title role. Up-and-coming directors Marcus Kryler and Fredrik Akerstrom, who directed scenes from the latest Battlefield 1 video game, will helm the film. John McClain, the writer, is also brand new on the scene!

Writer: John McClain

Details: 103 pages

I was going to review a movie today called “Your Name,” which is an animated film from Japan that is currently the second biggest box office hit in the country’s history.

So I watched it.

And it had to be… maybe the worst movie I’ve ever seen. Like, so bad that I didn’t even know what to criticize. Honestly, my “What I learned” would’ve been, “That, in Japan, you can apparently turn a nonsensical piece of garbage into a box office phenomenon.” Can somebody knowledgeable about Japanese cinema explain to me why this movie is so popular? Cause all I saw was a bunch of cliched big-eyed animated characters spewing pointless dialogue with little-to-no story.

“Cliche” might be a good place to start with today’s script, as the action-spy thriller is one giant cliche at this point. Introduce spy. Show them do something spy-like, usually something at a party where they have to steal a jump drive and download the contents. Show that they’re a badass assassin by beating someone up, always preceded by the line, “He/She moves with inhuman speed…” Have them go after their next mark, someone of the opposite sex. Have them fall for each other, making the job that much tougher. Oh, and don’t forget to throw a major twist in at the midpoint, usually that our hero’s trustworthy superior is working for the opposition.

Sigh.

This is why so many scripts are bad, guys: Genre Goggles (see “What I Learned” section for definition). One of your jobs as a screenwriter is to understand the limitations of the genre you’re writing in and have a plan for how you’re going to overcome them. Spy-Thrillers are dressed up B-movies so there isn’t a whole lot you can do with them. Or is there? Let’s check out Hummingbird and find out.

20-something London is one hell of an operative doing deep cover stuff for the agency, protecting America one mark at a time. At least that’s what she’s told. Before every mission, London must go through a strange process whereby six cards are shown to her. When the sixth card arrives, a hummingbird, she becomes… something else. A cold-hearted killer.

When London is sent after her next mark, Alex, the plan is to do away with him. But unfortunately she starts liking him. Then Alex drops a bombshell on her. The hummingbird card trigger is part of a program HE DESIGNED. And it’s basically turned her into an assassin clone. Or something like that, since I don’t know what an assassin clone is.

Oh, but it gets so much worse. And, since this is a major spoiler, I’d recommend you stop reading now if you don’t want to know the script’s big surprise. Okay, is the “no spoilers please” crowd gone? Kay. It turns out that London is a robot. Which she probably should’ve figured out due to never having to go to the bathroom. But who knows. Maybe she was programmed to forget she’s never gone to the bathroom.

Back home, London’s team realizes their asset has gone rogue and therefore send out other agents in the area to kill her. This means her and Alex must go on the run. But learning you’re a robot is never easy. I’m still recovering from my own learning I’m a robot moment back in 2011. And even if London does manage to escape this, what kind of normal life can a robot possibly lead?

So here’s my checklist for spy-thrillers. Again, this genre is one of the easiest genres to turn into generic forgettable blech. So take heed if you’re a lover of this genre.

1) Is the writer making an active attempt to avoid cliches?

Like I said, this genre is a cliche minefield. So I’m always looking to see if the writer knows this and is avoiding them. Hummingbird starts with a giant party (at the Louvre!) scene where the main character needs to steal a jump drive and transfer files. That’s a huge mark against the script.

2) Is there more depth to the characters than in your typical action-spy thriller?

I’m not looking for American Beauty level character introspection. But if the characters are too thin, it’s impossible for me to care about them. And when you combine that with cliched action, you might as well have had a robot write the script. You’re a human being. You’re supposed to bring humanity to your story. Unfortunately, this is hard to do even in genres that feature character development. So remember the character development tenets: Make them relatable, give them a past, give them a flaw, have them battling with something inside of themselves, give them compelling unresolved conflicts with other characters, and most of all: BE TRUTHFUL. Don’t have your characters act like movie automatons. Have them act like real people.

3) Are the set-pieces inventive?

These scripts tend to revolve around those big party scenes I mentioned above, as well as foot races and car chases. You have to try and give me versions of these I’ve never seen before. You may fail. But if you’re at least TRYING, that puts you ahead of 99% of the writers in this genre, who think that as long as their characters are running or racing, we’re interested. And remember, you don’t have to include any of those scenes. If you really want to be different, give us an action spy thriller that doesn’t use any of those moments.

4) Are the twists truly shocking?

If your twists amount to the boss secretly being a bad guy? You fail as a screenwriter and as a person. Twists are important in this genre. And you usually have 2-3 big ones. So work hard at making those twists surprising. Try to surprise even the most seasoned moviegoer. And, to that end, Hummingbird definitely succeeded.

The thing about Hummingbird is that its big twist does give the script something that’s unique enough to separate it from other scripts out there. Also (SPOILER!), because London is a robot, it allows the script to delve into character development in a way that most spy thrillers can’t. London has to question everything about herself, which provides the proceedings with some weight.

And yet, I never fully invested in this journey for some reason. I wanted to. But (spoiler!) the robot reveal was the highlight. And that happened all the way back in the first act. Nothing else that followed lived up to that moment, casting the rest of the script in a “decent but unremarkable” light.

I give the writer credit for doing something different though. And if these directors have vision, who knows? John Wick was a dog-revenge movie and was freaking awesome. So anything’s possible! :)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Genre Goggles – When you love a genre so much that you are unable to write away from its cliches and tropes, leading to a generic unmemorable experience.

Michael Voyer’s killer script that I reviewed yesterday, “The Young Hollywood Party Massacre” (which better end up on the Black List or I’m going to tickle Franklin Leonard to death), has reinvigorated me, given me hope that there is undiscovered talent out there just waiting for an opportunity. And hence, we begin another weekend of Amateur Offerings, scripts from real life screenwriters like yourselves, offered together in a Battle Royale winner-takes-all weekend tournament. Read the scripts, vote in the comments for your winner, top vote-getter gets a review next Friday.

To submit your script for a future Amateur Offerings, all you have to do is send me a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, why your script deserves a shot, to: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the ramifications of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or script title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every few weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Good luck. And may hope seep into the crevices of your heart!

Title: Gene X

Genre: super hero/sci-fi/action/thriller

Logline: Two men take an illegal drug which gives them temporary super powers and are pitted against each other by the company who make the same drug.

Why You Should Read: What’s original about this screenplay is that both heroes switch roles half way through. The hero becomes evil and the villain becomes good. I don’t see that in many films about super heroes. You were saying writers need to find a different spin on the over crowded super hero movies, so I think I’ve done that. What’s also good about my script is that it flows pretty well and there’s always something happening. Most of the characters are active, have goals and have motivation. I’m always trying to improve my writing, so that’s why I’ve submitted this. I’ve worked on 10 drafts for over two years now, so it’s ready to be criticized. I hope you like it.

Title: MATT AND BEN BURY A BODY

Genre: Comedy

Logline: After a sexual encounter goes terribly awry, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck find themselves on a collision course with a host of unsavory Austinites during their descent into the heart of darkness.

Why You Should Read: (nothing submitted)

Title: The Operative

Genre: Action/Thriller

Logline: When a young CIA trainee, working low-level assignments in Europe, is framed as a traitor, he discovers he holds the key to preventing global warfare and must outwit both ‘The Agency’, and the terrorist cell that hunts him, before they can incite World War 3.

Why You Should Read: I don’t have much to say in this section. I would rather the logline and the script speak for itself rather than trying to sell it to you. I will say my tastes are very commercial in nature as are all my stories. I love action, suspense and excitement, and always try to imbue that in the read. I hope it’s something you like. Thanks to everyone for checking it out.

Title: RUBBER TANK SQUAD

Genre: Action/drama (“Monuments Men” meets “Fury”)

Logline: During World War II a battle-hardened officer is demoted and assigned to protect a squad of “Special Troops”: painters, sound men, actors and costumers on a mission to hold back German forces with inflatable tanks and other decoy props. Based in part on a real WWII army unit.

Why You Should Read: The script was a finalist in several screenplay contests. A producer offered fifty bucks for a two year option. I declined. Now Bradley Cooper’s company has a competing project called “The Ghost Army,” based on a documentary about the subject.

Title: Work Of Art

Genre: Drama

Logline: A talented inner-city artist gets a shot at stardom when a renowned gallerist offers to mentor him, but when she persuades him to do increasingly heinous deeds in the name of art, he must decide how far he’ll go to achieve greatness.

Why You Should Read: With this story I saw an opportunity to do an urban take on movies like Whiplash and Black Swan, but instead of drumming or ballet this focuses on art, particularly painting. Although this story has a lot of my own experiences in it, it has something to say about the world that I hope will resonate with readers, and if not, will inform what my next step with this project should be.

Can it be true? A dying Carson is brought back to life by a fetus that kills people?

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Logline (from writer): A young, hip Hollywood couple on the verge of becoming first-time parents begin to fear their unborn baby is a murderous demon.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I used to work at a major talent agency. During my stint there, my wife was pregnant with our first child. This script was written over that period of time. Horror comedies are hard to pull off. That, coupled with a story that lampoons, among other things, big talent agencies seems like a recipe for disaster for an amateur writer. Which is pretty much why I wanted to write it. Or “needed to” is probably more accurate: I had to find a way to channel some of the negativity I was feeling about the biz, living in LA and bringing a baby into that world.

Writer: Michael Voyer

Details: 106 pages

In the world of screenplays, I’ve seen a lot of things.

I’ve seen men who kill.

I’ve seen women who kill.

I’ve seen teenagers who kill.

I’ve seen kids who kill.

I’ve even seen a baby who kills.

But I have never, until this moment, seen a fetus that kills.

And had you told me that there was any possibility going into this premise that I was going to enjoy myself? I would’ve informed your delusional ass that you were insane in the brain cage.

“Young Hollywood” introduces us to Colin and Bobbi Downs, a young married couple who are making it work in the trendy LA suburb of Silver Lake. Colin’s got a job at a major Hollywood agency. And Bobbi’s third-term pregnant, ready to turn this twosome into a triumvirate.

When Bobbi starts to have visions of a crazed Jamaican woman, we chalk it up to weird pregnancy hormone shit. That is until we learn about Colin’s lurid past.

Colin and his frat buddies (who include his best friend and neighbor, Don) used to fly down to Jamaica for Spring Break and go nuts. One night, Colin had sex with a wild Jamaican girl, who he unknowingly impregnated.

That girl, Constance, shows up in Los Angeles five years later to inform Colin of his bastard son, and also, his seed has since been cursed. The baby growing inside his wife is a demon ectomorph that has the power to leave the womb and kill things.

Naturally, Colin thinks this is bullshit. But when Don’s dog, and then one of his children, are murdered, it’s time to redefine “bullshit.” What do you want to reverse the curse, Colin asks Constance. In classic Hollywood fashion, she wants him to read her screenplay and make her famous!

Luckily, Colin’s boss happens to be looking for a horror script. But it’s probably going to take a miracle for him to like it. Constance isn’t exactly Aaron Sorkin. Meanwhile, Bobbi starts battling her own demons, namely, does she even want to have this baby? Has she ever wanted to have this baby? And now that she thinks about it, did she ever want to be with Colin in the first place?

It’s all going to come to a head in a “Young Hollywood” party for the ages.

Much like our characters’ reaction to their baby potentially being a demon, I wasn’t a believer at first. But the more I read of “Young Hollywood,” the more of a believer I became.

I’ll tell you the exact moment, actually, when I knew this wasn’t another AA script (average amateur). And I’ve been reading a lot of AA scripts lately, so I consider myself an expert. It was when we found out that Bobbi had this complex past where she chose to abort a child when she first met Colin, since she was afraid he’d leave if he found out she was pregnant.

So often in the screenplays I read, the only complex backstory the writer thinks about is the hero’s. Now occasionally, the slightly-less-lazy writer will go a step further and provide backstory for their secondary characters, but it’s always something generic, a screenwriting 101 box they can say they checked.

When a writer takes the time to find complex thoughtful backstories for more than one character? That script is usually worth reading. And I loved everything we learned through this couple’s backstory.

But what’s really amazing about “Young Hollywood” is the tone tightrope it walked. We have tragic child deaths sharing the same margins as voodoo witches promoting their new screenplay. And let’s not forget our killer fetus that slinks out of our wife’s uterus every night to get its killing fix in.

How did Voyer manage to make it work?

It’s simple really. He was more interested in these characters than he was the “gimmick” of his screenplay. That’s where so many writers go wrong. They’d take a premise like this, think up a bunch of goofy ways a uterus could kill someone, and fill the rest of the script with a half-ass exploration of a “struggling marriage.”

Colin and Bobbi are REALLY going through something here. Even if this was a normal baby, they’d still have issues to work through. It seems so simple when we see it in practice. But the reality is, we rarely get screenplays where characters and relationships are explored in a genuine way.

The problem with all these bad screenplays I read is that yes you have characters, yes they have flaws, yes these characters have issues with other characters, yes there’s conflict, yes there’s drama.

But none of it feels REAL. And it’s because the writers aren’t basing their choices on what real people would really have going on. They’re basing them on fakey movie reality where every choice is a variation of past movies they’ve seen.

I wasn’t surprised at all when I read Voyer’s “Why You Should Read” that he wrote this when his wife was pregnant and he was working at an agency. He was clearly working through some shit that was reflected in the characters and the situations, all of which felt truthful.

On top of all that, I had NO idea where the fuck this was going. And holy shit is that rare to experience. Every script I read has an inevitable quality to it that makes it seem like you’ve already read the outline before you read the script. This script had choice after choice that was ambitious, weird, unexpected, you name it.

When we killed a child? Wow.

When our villain promised to lift the curse if our hero read her screenplay? Didn’t see that coming!

The steady stream of backstory revelations? Ongoing wow.

And here’s the thing with choices, guys. I didn’t always like the choices. Some of the choices actually made me uncomfortable. But choices aren’t about being liked. Choices are chances. You’re taking a chance. And the safer the chance you take, the less of a reaction you’re going to get. The more dangerous the chance you take – whether they like your choice or not – they’re going to remember it.

Could I pick apart aspects of this script? Yeah. But like any good script, the weaknesses are actually what make it interesting. If we tidied everything up, the script would feel too “clean,” too “predictable.”

For example, I would’ve liked the comedy-to-horror ratio to have more comedy. I also would’ve liked for the final party to have higher stakes. But these are cosmetics. It doesn’t change the way you feel about these characters or how you react to this script’s twists and surprises.

This is the kind of script that makes me want to do more Amateur Offerings.

Screenplay link: The Young Hollywood Party Massacre

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: What do I mean when I say that writers don’t base their choices on truth, but rather past movies?

Well, let’s say a writer’s favorite movie is Jerry Maguire. And in this writer’s new script, their hero gets fired. Instead of getting into the head of their hero and asking what led to this firing and what he’s feeling in this moment and how would someone like that react in real life, they think, “Oh good, I get to write my big memorable firing scene like Jerry Maguire!” The last thing on their mind is truth. And if all you’re doing is writing variations of scenes from other films, nothing you write will ever resonate with anyone. Read that line again because it could be the difference between you becoming a professional screenwriter or not.

I’ve been reading some really boring scenes lately, guys. It still baffles me that writers view quality in scenes as optional. Like, “Okay, I know this scene isn’t great, but it’s only one scene, so the reader will have to deal.” You have to make every scene entertaining. Every one!

I know this is easier said than done. You read all these things in books about how a scene must a) move the plot forward, b) reveal something about the characters, c) integrate conflict, d) invisibly weave in exposition, e) avoid cliche, that if you somehow manage to do all of these things, you feel like you deserve a giant pat on the back! That readers should be all, “Man, you were so technically proficient there. I don’t care that the scene was boring.”

That’s why I say, screw all that!

Your first thought when creating a scene should be, “How can I make this scene entertaining?” Because none of that other stuff will matter if the reader isn’t entertained. After you figure out where the entertainment is going to come from, then figure out how you’re going to pull off the checkboxes.

Now, remember the basics for a scene. At least one character should want something important in the scene. It could be your hero. It could be your hero’s girlfriend. It could be the villain. Someone must want something. Then, you simply don’t want that character to achieve the goal easily. Something, or multiple things, should come up, so that the character must work hard for that goal.

Here are a few things a character might want in a scene.

A character might be going to a bar to find a girl to bring home.

A character might need to fire one of his employees.

A character might need to tell her boyfriend she’s pregnant.

A character might need to get home before curfew.

Always, always, have at least one character want something in a scene. And, yes, it’s okay if multiple characters want something in a scene. In fact, that’s where scenes get fun, when characters want opposing things. Now we have heads butting. We have conflict.

But the want is the key. “Want” is what drive’s the purpose of the scene, and pushes us towards our scene climax (which answers the question of whether the “want” was achieved or failed).

But that’s not even what this article is about. You guys should know that already. What I came here for today was to give you five FIXES for boring scenes. Say you followed the above advice yet no matter how many times you rewrote your scene, it still sucked. Join me… for FIVE SCENE FIXES!

Move from private to public: A lot of times a scene will suck when it’s just two characters alone. The audience feels safe and at ease in such a scenario, and that’s not how you want the audience to feel. You want them to be scared, anxious, unsettled, unsure. To achieve that, leave the private setting and place the characters in a public setting with the potential for interaction from outside sources.

Example: In a recent script I consulted on, our hero needed to ask a professor about something. In the story, the professor didn’t like the hero. Anyway, the writer had the hero show up at the professor’s lecture, sit down, wait for the lecture to end, then afterwards, when the students had left, talk privately with the professor and ask his questions. The scene was boring. I simply suggested that the professor put our hero on the spot during his lecture. Make him talk to him with 100 students backing him up. All of a sudden, with everyone listening in, a boring scene became entertaining.

Add a time constraint: It’s one of the simplest tricks in the book and yet it can turn the driest scene into a memorable one. If your characters have all the time in the world to talk and there’s nothing on the horizon that needs tending to, there’s a good chance the dialogue will be leisurely and, therefore, boring. By adding a time constraint you’ll find that, all of a sudden, your characters might not be able to say everything they wanted. They have to be more judicious about what they say. And if they’re not getting the answers they want, frustration starts to creep in, since time is running out!

Example: Another recent script I read. A soldier needs to ask her commander a series of questions. Originally, the writer had the soldier come to the commander’s office and ask away with all the time in the world. Borrrr-innnggg. I switched the scene to the commander giving the entire outfit a briefing, then our soldier needed to ask her questions as the commander hurriedly walked to his next meeting. Similar conversation, not enough time to get all her questions in, MUCH BETTER SCENE.

Up the stakes: A lot of times a scene sucks simply because there isn’t enough on the line. This goes back to the “want” we talked about earlier. If what the character wants isn’t that big of a deal, then the scene won’t feel important. The reader doesn’t know why they don’t care. They just know they don’t. As a solution, see if you can up the stakes in some way.

Example: Two loser friends are at a crowded LA bar, trying to get the bartender’s attention. But every time he walks by, he won’t look at them. It’s an okay scene if you play it for laughs. But we could make it better if we upped the stakes. Let’s say two gorgeous girls are nearby and they ask our heroes if they’ll buy them a drink. “Of course. Yeah.” This time, with each failed attempt to catch the bartender’s attention, we have two girls who become increasingly skittish (“You know what, we were on our way out anyway.”), and two guys who see their luck slipping away (“No, trust me. It’ll just take one second.”). We’ve become more invested in the “want” (the drinks) because there’s more on the line (the girls).

Add some sort of choice (and make that choice matter): A common scene I run into is one where the character does nothing. For example, the hero might be sitting in his car before work, staring forward, hating life. If there are no decisions to be made in a scene, is it even a scene? A scene needs to have action, and choice is a simple way to dictate action, as well as add suspense and unpredictability.

Example: Using that same scenario, let’s say that while our hero is staring forward, a woman drags her child up to the car parked in front of him (this happened to me once). The child is being difficult, resisting, and the mom is getting angry, becoming uncomfortably physical as she manhandles her child towards the door. It’s at the point where our hero should probably step in and do something. And hence we have our CHOICE. Is he going to get out and say something or isn’t he? This doesn’t mean when you need excitement in your script, add child abuse. The choice you add will depend on your story, your tone, and the type of character you’re exploring. But an important choice is a simple way to beef up a scene.

Add a secondary focus: When a character only has to concentrate on one thing, they can usually handle it easily. And once we feel like our hero has things under control, we relax. And if we’re relaxing, we’re becoming less interested in the story. A trick is to add a secondary focus for the hero, something else they have to worry about. This way, they’ll be spinning two plates instead of one. And guess what follows? Entertainment, baby.

Example: Let’s say we have a protagonist who’s a gambling addict. And a scene takes place where his wife is talking to him about problems in their marriage and what she needs from him. We’ve seen this scene before, right? It can certainly work on its own. But what if, during this talk, our gambler keeps checking the score on his phone of the game he bet this month’s mortgage on? This secondary focus adds another dimension to the scene so it it’s a little more dynamic.

In case you guys didn’t notice, there’s a theme here. Figure out what your character wants in the scene and make it difficult for them. Cause if whatever your character wants comes easy, you’ve written a boring scene.

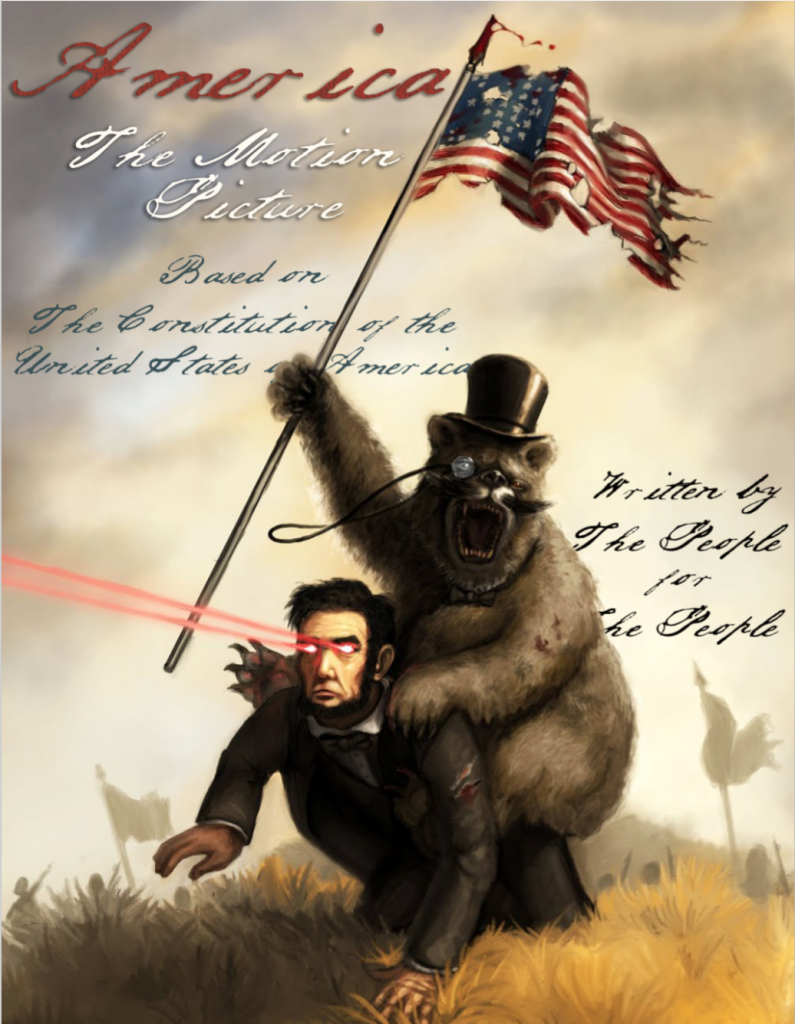

Genre: Comedy

Premise: George Washington puts together a band of renegade historical figures to take down Benedict Arnold the Werewolf and form the country he promised a dying Abraham Lincoln he would build, America.

About: This 2016 Black List script, which looked like it’d never rise above a fun curiosity, shocked the world last week when Netflix purchased it and decided to turn it into an animated film. Channing Tatum will voice George Washington and the film will be directed by Matt Thompson, one half of the beloved “Archer” team. The writer, Dave Callaham, is best known for writing The Expendables films. More recently, Callaham penned the upcoming Zombieland 2.

Writer: Dave Callaham

Details: 101 pages

First of all, I think Netflix is great. It’s one more outlet for creators to bring material to, and not only that, but unique material, the kind of material that takes chances. Now, after procuring America The Motion Picture, they’ve announced themselves as a new destination for animation. Just 15 years ago, there were three places that made animated movies. Now there’s triple that. Think about that. Spec screenwriters can actually write animation now!

However, Netflix is also learning that luring talent into their fold by offering them creative freedom has its drawbacks. Some of these movies and shows premiering on Netflix are so bad, it’s getting uncomfortable. Have you seen that new Brad Pitt War Machine trailer? It looks like everyone in it is acting in a high school play (by the way, when is Hollywood going to learn that war comedies stopped working in the 70s).

But here’s the scariest part. When a movie used to bomb in the theatrical world, there still came with it some notoriety. The promotion, the build-up, the press the movie got for bombing. People at least KNEW OF THE MOVIE. When a movie bombs on Netflix? It just… disappears, into a Netflix black hole, as if it never existed at all.

The point being, now that the sheen has worn off, the reality sets in. Netflix buying you doesn’t mean jack shit unless your movie connects with viewers. Will “America The Motion Picture” connect with people? Joint me for a little history lesson to find out.

While George Washington is enjoying a show with his best friend, Abraham Lincoln, his evil nemesis Benedict Arnold pops out of nowhere and kills Lincoln right in front of his face! Lincoln, with his dying breaths, makes Washington promise that he’ll create an independent country called America!

Knowing he can’t do this on his own, Washington puts together a super-team that includes demolitions expert Thomas Jefferson, transportation expert, Paul Revere, science expert Thomas Edison, and an Indian, Geronimo.

This all star team quickly corners Arnold, only to watch him BITE GERONIMO’S ARM OFF! That’s when the true nature of what they’re dealing with is revealed. Arnold is a werewolf! Which means the only way they can kill him is with a silver bullet. Now this was the 1700s, when silver bullets weren’t easy to come by. So off to the best blacksmith in the land!

The next place they know Arnold will be is at the Gettysburg Address. The problem is, they don’t know the address. So they spend countless days trying to figure out what the address of the Gettysburg Address is, until Washington uses some next level Davinci Code shit and figures out that the “A” in America is actually a code for “1” and therefore the address is 1 Merica Dr. And then the five blow up the Titanic.

Finally, after recruiting another well-known Washingten who spells his name with an ‘e,’ not an ‘o,’ and who is a dinosaur rancher who owns his own Tyrannosaurus Rex, the group attacks King James’ army. But will a T-Rex be enough to rid America of the redcoats for good? Spoiler Alert. Merica is on the map, isn’t it?

I refer to this kind of comedy as non sequitur comedy. Nothing really needs to make sense. Non sequitur comedy requires a writer with a huge imagination who’s naturally funny, the written equivalent of Robin Williams. Throw it all out there knowing not everything’s going to hit. But when it does, it will be HI-larious. And there are definitely hilarious moments in America The Motion Picture.

My favorite character was easily Edison, who would just scream out “SCIENCE!” and randomly be able to send a laser beam at people, vaporizing them instantly. Or you’d have all five heroes chasing someone on Paul Revere’s horse, and that someone would get on a boat and speed off, and Washington would ask, “Do you think your horse can leap across that water?” Paul Revere would reply, “That lake is 200 feet long.” “Well, do you?” Beat. “Yes. Yes I think he can.”

And so Revere would trot the horse back, make a run at it with all five people on, and the horse leapt… and make it all of four feet before falling in the water.

However, when the jokes weren’t hitting, you were stuck with a plot that wasn’t exactly Chinatown. I mean, it did have GSU! We had a goal (defeat King James), stakes (America’s independence) and urgency (they needed to defeat them before the Gettysberg Address).

But the comedy was so goofy that there wasn’t a lick of depth to anyone. Nobody was trying to overcome any sort of internal issue. With that said, I don’t know if you want that in non sequitur comedy. I think if you try to force character arcs into movies like this, they don’t work.

I’ve been reading the science fiction book, Rendezvous with Rama, recently. It’s a book that’s light on character, and heavy on the mystery behind a giant abandoned ship in our solar system. I later found out that a different author wrote a sequel that was universally panned. Everybody seemed to have the same reaction to the sequel: “What was so great about the first Rama was that it focused exclusively on the mystery,” they said. “Rama 2 sucked because it was all about characters and drama.”

Point being, sometimes you have to lay off the rules of the craft. If Screenwriting 101 books tell you you have to insert “A” whenever you do “B” but as you’re writing “B” you’re thinking, “I don’t think it would work if I added A.” Well, then maybe you shouldn’t add “A.”

For example, if you’re writing The Martian and you’re thinking, “I know screenwriting sites like Scriptshadow say I should give the story a contained time frame. But geez, I don’t think that’s going to work for a movie like this. I think this movie only works if you let it breathe and extend it out over a long period of time.” Then go against the rule.

Everything is a case by case basis, guys. So if you’re writing a goofy comedy like this one and adding character arcs feels wrong, don’t add them! Go by what you feel.

As long as you’re good at delivering what the audience wants, nothing else matters. And America The Motion Picture delivers exactly what its audience wants.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Extremely goofy comedies like this do not need character development (inner conflict, vices, character arcs). But they do require some sort of structure. America The Motion Picture has one giant goal (defeat King James and gain independence) and a series of smaller goals (create a silver bullet, find the Gettysburg Address, etc.) that always keep the plot moving (whenever there’s a nearby goal, the plot is moving towards that goal). If you try and write non sequitur comedy without structure for 110 pages, the reader will probably want to murder you.