Genre: Horror/Slasher

Premise: After their friends run a supposedly haunted red light and suffer horrible deaths, three disbelieving teens run the same red light to dispel small town superstition, only to find themselves the next targets of a sinister figure hellbent on revenge.

About: I’ve been teaching Pre-Kindergarten for seven years now, so trust me — I know horror. Besides wanting to bring the slasher film back for the Z Generation, I’ve always wanted to write a movie that made an ordinary thing seem terrifying. Think of what Jaws did for going swimming, or Shallow Hal for, uh, going swimming.

One night, while sitting at an empty intersection waiting for the light to change, I found myself coming up with reasons not to go through it. A car could smash into me. I could get pulled over. An unflattering photo of me taken from a traffic camera could appear in my mail. But it wasn’t until I convinced myself the vengeful ghost of a woman — a woman wrongfully killed at that very intersection by another red light runner — would follow me home that I knew I had something special.

I’m confident anyone who reads my script will never go through a traffic light the same way again. But don’t just take my word for it. Professional script consultant Danny Manus gave it a strong consider and called it, “A fast and enjoyable read with a solid climax, a couple good twists in the plot, some strong scare moments, suspenseful scenes, and enough gore to satisfy PG-13 horror fans while still having a solid mystery.”

So how isn’t this a movie yet? How am I still without a manager or agent? How did I keep you reading this long without the exchange of payment or sexual favors? Maybe you can educate an educator. I’m hoping you’ll give my script the chance for some extra attention and critique, but more importantly, I just want everybody reading it to have fun. Because I had a blast writing it.

Writer: Chris Shamburger

Details: 103 pages

So, honest first thoughts when I read this logline:

A haunted red light?

Ehhhh… I wasn’t too confident.

It seemed a bit goofy.

But then I thought about The Ring, one of the most popular horror movies of all time, and wondered, “Is it any less goofy than that? A haunted video tape?”

Then again, the great thing about The Ring was that the video tape was the ultimate visual freak fest. What you saw on that tape chilled you to the bone. It really helped you buy into the premise.

I’m not convinced a red light does that. But let’s find out. WAIT! Hold on. Press the walk sign button. Okay… and it’s green now.

We start off with an eclectic mix of high schoolers and college kids. There’s 18 year old Nikki, a young black woman with some sass. There’s Xander, 19 and athletic. There’s Hannah, 17 years old and eager to start going to college parties. And then there’s some periphery players, like Hannah’s older brother Jimmy, who treats her like a misbehaving child, and Rebecca, Jimmy’s bitchy ex-girlfriend.

So Nikki, Xander, and Hannah head to a college party at ASU where the talk is of a recent group of kids who ran a red light and all but one got butchered at a diner afterwards. When Xander hears that the operating theory is that they were butchered by a ghost who’d been killed when hit by somebody who ran the same red light, Xander wants to run the light too.

So he recruits Nikki and Hannah under the pretense that they’ll hashtag it and become internet famous, only to learn afterwards that there may be more truth to the story than he originally thought. When strange things start happening to them, the three each separately start investigating this woman who was killed, and find out some disturbing things about the incident.

Eventually, as you would expect, teenagers start dying, and the question becomes, is this really a ghost, or might it be a real life killer who’s big on road safety.

Okay so, we’ve got a lot of beginner mistakes here and I hope that by highlighting them, I can help Chris as well as other writers out. Remember that readers are quick to pick up on red flags. And red flags are like ants. Where there’s one, there are usually more. And remember when I said I was skeptical of the premise? That tends to be a red flag out of the gate. When the premise isn’t on point, other things tend not to be either. Unfortunately, that was the case here.

Starting with the opening scene where something immediately jumped out at me. Our drunk teenagers are in a car, but instead of acting like drunk teenagers, they’re spouting out functional backstory-laden dialogue such as, “It’s Rebecca.” “I haven’t heard that name in a while.” “We just started talking again.” “Why?” (remember that leading questions are bad!), “She’s the new president of Alpha Omega Pi.”

Does that sound to you like drunk high school kids? I remember the conversations myself and fellow drunken high school kids had and they were nothing like that. There were random screams and woops about nothing in particular. Someone would say out of nowhere, “We should go to New Orleans!” Someone would always mention some girl that someone recently banged and that “we should call her.” There’d be lots of laughter.

You have to honor the truth of the moment. If you prioritize screenwriting conventions over truth, your scene won’t feel honest, and that’s the case here.

Next on the docket is this description: “He’s so lit, you could probably read a book by him.” It took me several reads before I finally understood what the writer was saying. These overly cute descriptions are almost always the sign of a beginner. Pros prioritize storytelling over everything. They don’t want to break the suspension of disbelief and understand that lines like this can do that.

The exception is when they’re built into the style of the script and the writer is REALLY good at it. When cute lines like this appear out of nowhere, they’re lone wolves and draw attention. I’d avoid them.

Next you have the dialogue. One of the genres where dialogue is extremely important is teen movies. Teenagers are often at the forefront of whatever slang is dominating the zeitgeist, and seek to one-up one another with the latest burn or turn of phrase. For these reasons, when the dialogue in a teen movie is boring, it’s a huge mark against the script.

The dialogue here was very functional, very robotic, and didn’t sound like teenagers at all. When Hannah’s brother’s ex runs into her, she says, “And Hannah, when you see Jimmy again, please tell him I said hi.” That sounds like a 35 year old speaking. Not someone in college. The script was littered with dialogue like that. No style, no fun, no slang. There were a few sections that eschewed this, but not enough.

The next red flag didn’t take long to appear. When they go to this party, Matt, the lone survivor from the first gang to run the red light, gets out of jail after being questioned, and goes straight to this party.

So let me get this straight. You’ve just watched your friends die horrible deaths. The police think you may have done it. And the first thing you do when they release you is head to a party by yourself? But it gets worse. The first thing Matt does when he gets there is go to a bathroom, sit in a stall, and cry???

Why did he come to the party if all he was going to do was cry in a stall? Soon after, the stall is burned to the ground with Matt in it, and we have our answer. The writer wanted to kill Matt in this bathroom. He didn’t care how he got the character there, as long as he could have his bathroom killing scene.

This is another difference between amateurs and pros. Pros will find logical motivations for characters to do things. Amateurs don’t care about that stuff. They’ll pace their character through the most illogical set of actions (showing up at a party the second you’ve been released from jail for being a murder suspect, heading to the bathroom to cry by yourself) to get them to the scene they want to write.

This is why when people say that Hollywood movies are terribly written, I chuckle. Yes, there is badly written professional material. But the bad in those movies is “professional bad.” It’s a whole different level from amateur bad.

On the plus side, the premise began to win me over as the script went on. I thought it was clever to make the ghost woman an investigator who was in the middle of trying to find a missing child. It brought another level of mystery to the teenagers’ investigation. I mean who knows. I could see this being a direct-to-digital horror title. Why not? It has a great title. It’s an easy-to-understand concept. However, before you can rope in the people necessary to make this movie, you have to take care of these basic mistakes.

Script link: Red Light

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Another red flag is character descriptions that are purely physical. Here’s Xander’s character description: “XANDER, 19, stands on the front step, newspaper in hand. Lean, athletic build. Strong chin. He’s a six foot tall drink of water.” It’s almost always better to convey something about the character in their description. For example, a simple word like “mischievous” tells us so much more than that “he’s a tall drink of water.”

Week 12!

Week 3 of the rewrite!

If you’re new to the Scriptshadow Script Challenge, here are all the previous posts…

WEEK 0

WEEK 1

WEEK 2

WEEK 3

WEEK 4

WEEK 5

WEEK 6

WEEK 7

WEEK 8

WEEK 9

WEEK 10

WEEK 11

You should be halfway through your rewrite at this point. But if you aren’t, don’t get down on yourself. Yes, the Scriptshadow Write A Script Tournament is coming up soon, but next week I’ll announce that you may have more time than you think to get your script ready. So stay strong and KEEP WRITING EVERY DAY.

One of the most common e-mails I’ve been getting is, “What is the outline for a screenplay supposed to look like?” I thought I’d get into that today because every time you rewrite a script (and you may rewrite a single script up to 30 times), you should start with an outline. An outline allows you to see your script in macro form and therefore have a better sense of how a scene or a moment fits within the grander state of things.

Now everyone outlines differently. Some people like to be extremely specific, some more general. I find that on a first draft, your outline will be big and lumbering with lots of detail. Then, as each draft goes on and less of your script needs to be rewritten, the outlines will become smaller and more manageable.

I know some people like to write an outline then NOT LOOK AT IT AT ALL during their rewrite. Their belief is that if they can’t remember what they wrote, it’s probably not important enough to be in the script. Of course, they still have the outline to draw upon if they get really stuck.

Before I get into what you’ll specifically write in an outline, here’s the framework for what an entire outline should look like. Note that the number of scenes is just a guideline. Fast-paced scripts will tend to have short and therefore more scenes. Slower period-piece type scripts will likely have longer and therefore fewer scenes. This will break down to between 12 and 15 scenes for each section, which means your script will have between 50-60 scenes. And yes, it’s okay to go a little lower than 50 and a little higher than 60. It all depends on what type of script you’re writing.

ACT 1

SCENES 1-12

ACT 2 (PART 1)

SCENES 13-28

MIDPOINT

ACT 2 (PART 2)

SCENES 29-46

ACT 3

SCENES 47-55

THE END

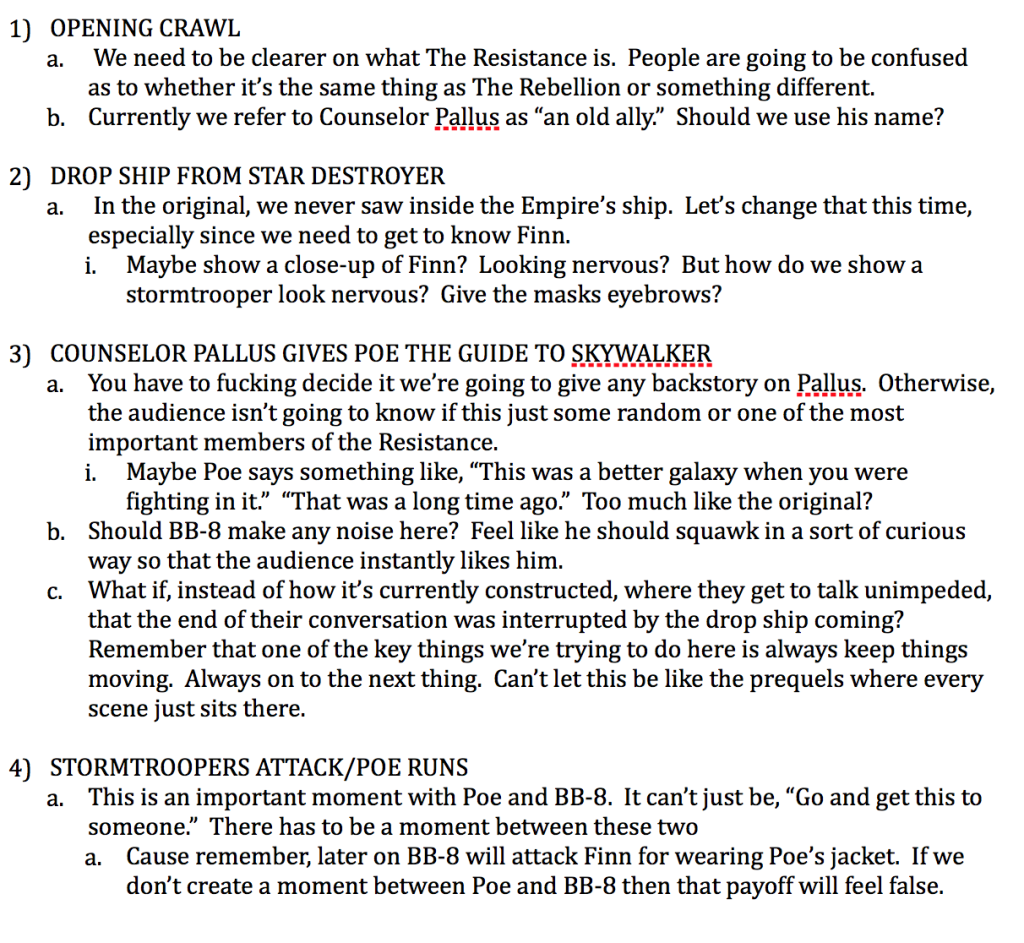

Unfortunately, I can’t do an entire outline from start to finish. So I’ll do a small section and you can use that as a guideline for the entire outline. Since HTML doesn’t allow you to outline without having a degree in nuclear fission, I’ll have to take a screenshot and post it as an image. Here’s a fictional outline for The Force Awakens. Sorry if it’s a little small.

Hope this helps. Next week I’ll announce the official time table for tournament submissions. Get to writing!

Rewrite Goal (Week 12): Three-quarter point of the script (around page 75-85)!

Today’s script may be the strangest combo I’ve ever read. Forrest Gump meets Clockwork Orange.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: We follow the life of Cosmo Hopper, a drifter whose life has been influenced by several major historical events, including the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Challenger Explosion, the Rodney King inspired riots, and the first Iraq War.

About: This is one of the two scripts Eric Bress, writer of The Butterfly Effect, sold back-to-back last year. I loved the first one and got a lot of flak for it from you guys. Well, we’re back with the second one, which is a lot more ambitious. Let’s check it out!

Writer: Eric Bress

Details: 107 pages – 1st draft

Guess what time it is?

TIME TO TALK ABOUT VOICE FOR THE 684,233rd time!

Raise your hand if you’re tired of hearing about voice? Okay, now ask me if I care. Go ahead. Ask me.

TOUGH!

See, the nice thing about reading an Eric Bress script is that it won’t be like anything else you’ve read before. We have death by falling Challenger Shuttle explosion debris in this movie. Try and top that.

On the flip side, if all you do is rewrite the movies you’ve loved from your past, you’re not going to write anything memorable. That’s not to say you can’t write an entertaining product. If your technique is good, if you understand basic storytelling (suspense, irony, dramatic irony, character development, conflict, anticipation, mystery), you can still write something solid. But you’ll never write something great unless it comes uniquely from you.

I mean, yes, I liked The Force Awakens. But I’ll be the first to admit that JJ didn’t bring anything new to it. He didn’t bring any voice. He brought his love and passion for the source material. And that was enough to get me excited about Star Wars again. But The Force Awakens never had a chance to be great because there wasn’t a unique voice behind it.

39 year old Cosmo Hopper is a homeless vagrant who’s just been accused of burning down a building and trying to kill everyone inside of it. Luckily, nobody died, but the interrogating officer wants to know why the fuck Cosmo would do such a thing. So Cosmo decides to tell the officer his life story.

Cut to Cosmo at seven years old when he loses his mother to cancer. That means his care is transferred over to his estranged weirdo father, one of those low-lifes who thinks he’s a scientist because he drinks a lot of beer and reads books.

Dad makes Cosmo his own personal guinea pig, putting him through a series of tests like holding him underwater for minutes at a time, walking on glass and hot coals, covering Cosmo’s favorite horse with gasoline and having Cosmo walk him through a thin path with fire on each side. Yeah, your basic nut job shit.

Lucky for Cosmo, his father dies one day when the two are fishing. They’re in Florida at the time, and watch in horror as the Challenger shuttle blows up in the sky and eventually rains down its debris on the lake. His father is hit by one of the chunks from the shuttle and that’s all she wrote.

Cosmo, now 19, says goodbye to his best friend and love of his life, Rosanna, and heads off to find his grandparents. He stows away on a crabbing boat (the most dangerous job in the world) eventually ending up in Germany during the fall of the Berlin Wall. He finally finds love again with his grandparents, and things seem to be going well.

Eventually, Cosmo heads off to fight in the Iraq war, where he sees the kind of death and mutilation that even someone with the most fucked up father in the universe is prepared for. At one point, he’s responsible for taking all the blown up soldier bits and, like a puzzle, putting them back together again.

All during this time, Cosmo ponders the meaning of life, of the universe, with a particular obsession over the number 17 (“I’d seen 17 men die in my meat wagon and 17 explosions since then. The flight home was 17 hours and left at 17:00 hours.”) and longs to be back with the only thing that makes him whole – Rosanna.

But is it too late for them? Is it too late for Cosmo? Has he seen too much? Experienced too much? Not even Cosmo may be able to answer that question.

You ever wonder what Forrest Gump may have looked like had it been directed by David Lynch, with second unit directing by Harmony Korine? Yeah, me too. Well, it would probably look something like this. This is bizarro world shit up in here, and whether you love it or hate it will depend on how fucked up you are in the head.

Structurally, it’s kind of a mess. We’re randomly jumping through time to key historic moments both in our hero’s and our planet’s lives. But Bress does use a device to make it more palatable, and it’s one all screenwriters should be aware of. He uses the “base camp” technique.

So last week, I was consulting on a script for a writer and his story was jumping all over the place. We were in Egypt for awhile, then we spent some time on a ship, then we spent time in business boardrooms, then we followed the construction of a soccer stadium. The script was frustrating to read because it couldn’t focus on one thing.

You could argue American Drifter is the same way – with a tweak. Bress establishes a “base camp” at the beginning of the story – the interrogation of Cosmo Hopper for burning down a building. By establishing a base camp, wherever we travel in our story, no matter how far or how weird, we have this base camp to come back to.

Now ideally, you want a storyline going on with your base camp, something the reader actually cares about. That way, when we’re in Berlin or a crabbing ship or Florida during the Challenger explosion, we’re always thinking in the back of our minds, “I wonder if he’s guilty of burning down that building.” This device basically gives a shapeless story shape.

Now is the base camp storyline here great? No. But we are dealing with a first draft. And I assume Bress has improved it since. There didn’t seem to be big enough stakes attached to his burning down of this building. Nobody died. It was more about, was this a dry-run for Cosmo to do something even worse. And since he was already captured, I wasn’t worried about that.

A base camp movie that worked better was Source Code. Whenever we went back to base camp (our hero stuck in that room with the controllers), it was made clear to us that time was running out. If they didn’t find this bomb soon, another bigger bomb would blow up, killing thousands. So the interrogation actually had some stakes attached to it.

Still, this script is unlike anything I’ve read all year. It’s not perfect. It’s not something that will appeal to everyone. But in a sea of scripts that all read the same, this is a refreshing diversion I was happy to take.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Anybody you’ve ever been passionate about – good or bad – has a strong voice. M. Night, Paul Thomas Anderson, Michael Bay, Quentin Tarantino. The less passionate you are about someone, the less defined their voice is. Again, you can still enjoy a non-voicy person. But their films tend to inspire less of a reaction. So ask yourself when you’re writing – am I writing the kind of thing that wouldn’t offend a single person? That wouldn’t inspire passion one way or another? If the answer is no, you’re probably not drawing deeply enough within yourself to explore your unique point of view on the world.

What I learned 2: The bigger your movie, the harder it is to inject voice into it. Voice often divides people. And the biggest movies out there can’t afford to divide people. They have to appeal to everyone. So if you’re writing a huge 150 million dollar movie, don’t worry too much about injecting the script with a controversial voice.

Might today’s action spec be the most manly ever reviewed on Scriptshadow???

Genre: Action

Premise: A group of badass mercenaries are hired for the most difficult security detail in the world, protecting a Mexican politician targeted by the biggest cartel boss in the country.

About: Originally written by Predators scribe, Alex Litvak, Five Against a Bullet pulled in the king of cool, Joe Carnahan, to rewrite the script and direct the film.

Writers: Joe Carnahan rewrite (original script by Alex Litvak)

Details: 121 pages

Here’s my question. How do you turn a script like this into the next Fast and Furious franchise as opposed to the next straight-to-digital franchise? Cause honestly, it could go either way. It’s got five cool testosterone-busting leads for actors, the kind of badass parts you could see action actors playing over and over. Yet if they don’t get the right mix of hot faces and money, it doesn’t matter how good of a director Carnahan is. This will never get a wide release.

“Five” follows five badass dudes, starting with the leader, Frank, a man of few words who can get out of any situation by always expecting the worst. There’s Simon, a mouthy Australian desperate to prove he’s got the biggest dick in the room. Terry, a weirdo Japanese-American who can hardly be bothered to look up from whatever video game he’s playing. Vic, a slimy private detective who will bang your wife the second you hire him to see if she’s cheating on you. And finally, Rico, a former bodyguard who failed to protect his boss from one of the most ruthless cartels in the country.

These five are brought in to protect Alvaro Diaz, a Mayoral candidate in a large Mexican City. All they have to do is keep him alive for three weeks, until the election is over. The problem is, every cartel member and their step-mom wants to off this guy as he’s the only candidate with the balls to stand up to them.

The script follows our team as they try and figure out how to navigate even the most mundane of tasks, like traveling a few blocks. When the bounty on Diaz’s head is raised to 20 million, even the girls playing hopscotch are libel to slit your throat. And the longer this goes on, the more Frank worries he may have gotten himself in over his head.

When the heat of the campaign eclipses the heat of an average day in Mexico, Diaz decides to confront the man who wants his head, Montero, face-to-face. He lets him know that he’s not backing down, and if Montero wants to kill him, he’s going to have to pull something out of his ass. Frank, for the record, is not a fan of that challenge.

Eventually, when gang members start showing up at locations in advance of our team, Frank figures out they’ve got a mole. If he doesn’t flush out that mole quickly, there is no way they’ll make it anywhere close to election day. And we’re not just talking about Diaz. We’re talking about every single one of them.

So what is the difference between a straight-to-video balls-to-the-wall action flick and the next Fast and Furious franchise? Fuck if I know. But if I had to guess, I’d say eliminating as much generic as you can from your action movie. If all you have is guys shooting at each other and getting in car chases, it’s likely you have a boring action movie.

With Fast and Furious, as cheesy as the original was, it took place in a world (underground car racing) that hadn’t been explored much on the big screen. This is the unheralded benefit of a unique concept. Just by the nature of it being unique, most of the scenes you write will be unique without you even having to think about it.

Five Against A Bullet straddles the line between that world and the generic world (we get plenty of ubiquitous Mexican standoffs) but comes out on top strictly because of how good of a writer Carnahan is. I’m serious. This guy writes action better than anyone in town, and there isn’t anybody even close. When a car crashes in a Carnahan script it doesn’t “flip five times before coming to a stop.” It “barrel rolls over and over, vomiting metal and glass as it slides to a shuddering halt in the middle of the freeway.” I grew a beard reading this script it was so manly.

Also, Carnahan knows that the secret ingredient in an action movie is non-action scenes. If every scene is people shooting each other up, the audience gets bored. You have to find ways to mix it up.

One of the best scenes in Five Against A Bullet is when our guys are driving through town at night and get stopped by a police blockade. The police chief, obviously in bed with Montero, tells Diaz that his team is illegally carrying firearms and that the cars they’re driving aren’t up to code. Unfortunately, he apologizes, he’ll need to take both. This leaves the entire team in the middle of the city, in the middle of the night, without vehicles or a way to defend themselves. The suspense and anticipation this situation presents is far more engaging than yet another “Pew pew pew! Got’em!” gunfight.

Then there’s the mole stuff. Someone in the group is informing Montero where they’re going to be ahead of time. So Frank has to figure out who it is. I was far more engaged in this mystery than I was the next car chase. And a lot of newbie action writers don’t realize this. They just write the most elaborate gun fights they can think of.

My big problem with the script was the structure. I’ve mentioned this before. I don’t like stories that are built on waiting. I like it when the characters are actively going out and trying to achieve a goal (like a heist, which is what one of the recent Fast and Furious films was about).

Five Against A Bullet is all about waiting for someone else (Montero) to make a move, and then repeatedly reacting to that move. It’s not to say that can’t work. There’s a level of suspense involved in “Where is the next attack going to come from?” But movies tend to work best when the main character is pursuing something as opposed to waiting on others to pursue something. The latter results in a more passive story, which is particularly dangerous when you’re writing a testosterone-filled action film.

But again, Carnahan is such a good action writer, he makes it work. And to that end, I implore ALL action writers to find and read this script. Particularly, pay attention to the detail Carnahan adds. It makes everything he writes feel so much more tactile than your average action spec. You really feel like you’re there. For example, here’s how he has one of his characters introducing the cars they’ll be using to drive the team around: “V-12 short stroke switchout engines. These cars will turn 600 horses apiece and look like everyday drivers. Reinforced bumpers, so we can punch through roadblocks. Run flat tires. UL Level 10 Bullet-resistant glass. And that’s as much as 50k gets for three cars.” A bit different from your average newbie description of “A badass muscle car” no?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Look beyond the action for the best scenes in an action movie. Use tried-and-true storytelling tools to find scenes instead. Mystery (which one of them is the mole?) and suspense (place them in the middle of town, at night, with no way to defend themselves). You obviously want action in action movies. But if ALL you’re offering is action, then all you’re offering is boredom.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: When ghosts take over New York City, a team of female scientists with a strict, “No men allowed” policy, must figure out a way to control the supernatural outbreak.

About: One of the most storied project developments in cinema history. 30 years of trying to get a third Ghostbusters made. There have been numerous scripts written by an endless line of writers. Bill Murray refused to read any of the scripts for some reason, preventing the project from ever moving forward. Eventually, a “young corps of Ghostbusters” idea was thrown onto the table. But Sony strangely split that plan into two separate scripts taking two separate angles on the idea. That led to even more confusion and frustration and never went anywhere. A few years ago, Paul Feig (Bridesmaids, The Heat) felt that he could bring something new to the franchise with an all-female cast. Desperation reared its ugly head, the studio greenlighted the film before Feig could change his mind, and for the last two years, the internet attacked the odd angled remake, culminating in a Youtube war where the Ghostbusters trailer became the most disliked trailer of all time. The film finally came out this weekend. Time to figure out how it was received!

Writers: Katie Dippold & Paul Feig (based on the film, “Ghostbusters” written by Dan Akroyd and Harold Ramis and directed by Ivan Reitman).

Details: 116 minutes long

Oh man. Ghostbusters.

After all these attempts. After all these scripts. After all the Dan Akroyd interviews promising another Ghostbusters.

And we’re finally here, 30 years later, a finished product in hand.

I’m sure you’re asking the same question as I.

Was it worth the wait???

The answer can be found in Ghostbusters’ opening weekend take: $45 million.

I think that says it all, right? 45 million dollars. It’s not exactly a bust. It’s not exactly a hit. It just “is.” And that’s the best way to describe the new Ghostbusters. It just “is.”

So what happened? How did this film end up in box office purgatory, critical consensus purgatory, audience consensus purgatory?

I’ll tell you how. Because nobody involved wanted to make it.

Including the most important person on the project – THE DIRECTOR! That’s right. Paul Feig turned this down. He only later agreed to do it so he could get back together with his girl posse. And thus this passionless project was born.

Contrast this with the original Ghostbusters. Have you read any of the interviews from that time? Dan Akroyd was OBSESSED with this idea. He was PASSIONATE about this idea. This was his baby. And that’s the biggest difference between the original and this alternate universe version.

Passion.

I mean when you see Akroyd excitedly sliding down that pole in the original, that’s genuine excitement! His eyes tell us everything: “Can you believe we’re making this!?”

There isn’t a single person on this cast or behind the camera that would slide down a pole for this movie. And that’s why we have a lame Ghostbusters. When you walk out of the film thinking, “Something was missing and I can’t put my finger on what.” THAT’S the “what.”

And that’s the real reason behind the blowback. The Ghostbusters people want to paint it as misogyny because it’s the narrative that favors them. But the reality is, this movie got greenlit to take advantage of a hot trend – comedies centered around females. NOT because someone who loved and cared about Ghostbusters wanted to share it with the world.

Now you may reply with, “Wait, Carson. What about Star Wars. Didn’t they do the same thing with that movie? Wasn’t that all about the money?” One big difference. They hired people WHO CARED about Star Wars. Who would’ve made it for free. Who would’ve given up their first born to direct a Star Wars movie. That’s not the case with this Ghostbusters reboot and everybody involved knows it.

Find me one interview in the past 20 years of Kristin Wiig or Melissa McCarthy or Paul Feig citing Ghostbusters as an inspiration. You won’t find it. I’d be willing to bet Wiig only did this franchise as a favor to Feig for jump-starting her career.

By this point you’re probably desperate to know what this movie is about. And by “desperate” I mean you couldn’t care less. Too bad. I’m going to tell you anyway. A group of scientists with an interest in the paranormal hear that real ghosts are invading the city and start a business (Ghostbusters) to capture those ghosts.

The difference between this and the original is that instead of our three Ghostbusters being buddies, core members Erin (Kristen Wiig) and Abby (Melissa McCarthy) USED to be friends, and don’t get along anymore. They’ve also added a street-wise expert on New York City (Leslie Jones) and the lamest villain this side of a Saturday morning cartoon.

Despite the overall lameness of the movie, as far as screenwriting goes, there are some things worth talking about, starting with that broken friendship.

When I went back to watch the original Ghostbusters, a movie that came out before there was a single screenwriting book on the market, I noticed there weren’t any issues with the friends. They were one big happy unit.

Whereas Ghostbusters 2016 was made during a time when there are 100+ screenwriting books on the market (mine included) drilling into your head that you have to explore characters, explore characters, EXPLORE CHARACTERS. Hence, in this new modern Ghostbusters, we have a broken relationship at the center of the film.

So the question becomes, has this newfound obsession with conflict-heavy relationships made storytelling better or worse? Are we overthinking our screenplays when it’s clear, from the original Ghostbusters’ success, that eschewing character development, at least in some cases, results in a better film?

The answer to this is complicated. Good character development always trumps good non-character development. But if your character development is uninspired, hackneyed, or lazy, than the script would’ve been better off without it. And that’s how I feel here. The Erin and Abby riff wasn’t bad. But there’s a definite “Screenwriting 101” vibe to it, as if the script needed to be approved by a USC professor before Sony could read it.

A bigger issue here is the lack of economic storytelling. Feig seems to come from the Judd Apatow school of directing, which is to say, the more, the better. But movies, especially comedies, always work best when the story is streamlined and all of the fat is stripped away.

I can point to a couple of examples for you. In the original Ghostbusters, the secretary is just there answering phones one day. She doesn’t get some grand entrance or interview. That would’ve slowed the story down. This allows us to move through that section of the story quickly.

In the new Ghostbusters, they stop the plot cold to add an interview scene for Chris Hemsworth’s character. Now is this scene a crime against screenwriting? No. I’m not saying never write an interview scene. In fact, I bet they even shot one for the original Ghostbusters secretary.

But here’s the difference. If they did shoot that scene in the original, they cut it. Feig, on the other hand, more concerned with a couple extra jokes, kept his unnecessary scene intact. And it was choices like this – keeping unnecessary scenes around instead of deleting them – that slowed this movie to a crawl.

A more blatant example of this occurs near the middle of the film. We get this weird back-alley “test out our new Ghostbusters weapons” scene. The scene has the requisite number of explosions, prat falls, and variations of “Oh snap.” And the scene is, at best, okay.

BUT IT DOESN’T PUSH THE STORY FORWARD!

Here we are, in the middle of the script. The story has already slowed to a crawl. The audience is getting bored. And you place a scene in the movie that has NOTHING TO DO with the story. It’s just characters goofing around. That’s a screenwriting sin right there. And for neither Feig or Dippold to realize this and cut the scene out, proves why this film was doomed.

It goes back to passion. When there’s no passion, you don’t care about getting it perfect. You care about goofing around and having fun on set. A director passionate about this material would’ve known that that scene wasn’t necessary.

And then there are things beyond the script that irk me. Like Paul Feig talking about Chris Hemsworth. When asked by Deadline what he thought of Hemsworth, this is what he said: “Without hyperbole, I think he’s the next Cary Grant, if he continues on the comedy route.” I mean, seriously? Give me a fucking break. At BEST Chris Hemsworth was an above-average surprise. Cary fucking Grant? Right. And Melissa McCarthy is the next Audrey Hepburn.

This is desperate over-selling, which tells you just how little confidence Feig has in his product. And I think if you strapped Feig to a lie detector and asked him if he could do it all over again, would he have made this movie, he’d tell you unequivocally, no. Which is ironic. Since it doesn’t feel like a new Ghostbusters has been made anyway.

Who you gonna call? Amy Pascal. To tell her this franchise is dead.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Reverse dynamics. This works well in comedy. What you do is you write a scene where one character is very dominant and the other submissive. Then, later in the script, you find a way to reverse their roles and play the scene over again. So in the original Ghostbusters, Venkman (Bill Murray) comes over to Dana’s (Sigourney Weaver) place to look for ghosts, but he’s really trying to make a move on her. She’s disgusted by him and eventually kicks him out. Later on, Venkman comes over again, but this time Dana is possessed by Gozer, who desperately wants to have sex with a human. So now it’s Dana who’s putting the moves on Venkman and Venkman’s resisting. We never get anything close to this clever in the 2016 Ghostbusters, of course.