Search Results for: the wall

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Ten years after a group of girlfriends bet on which of them would be the last to get married, their adult lives and relationships are completely upended when they discover the $80 they drunkenly invested in Bitcoin

is now worth $5.2 million.

About: We’ve definitely got the best name of all the Black List writers with this script: Daisygreen Stenhouse. Stenhouse writes with Liv Auerbach. Both are new enough to professional screenwriting as this is their first notable script, which finished on last year’s Black List with 6 votes.

Writers: Liv Auerbach & Daisygreen Stenhouse

Details: 97 pages

Anna Kendrick for Skyler?

Anna Kendrick for Skyler?

You’ll have to excuse me if I sound a little off-kilter today. About a year ago I lost the back up set of my keys and unfortunately, the remaining keys all say “do not duplicate” on them so I’ve spent the last year putting off getting a new back up set since I knew it would be such a hassle.

Then yesterday somebody told me that the whole “do not duplicate” thing is not legally binding. You can go to any hardware store and they’ll ignore it, copying the key for you! When the HEEEEEELLLL did this happen?? I feel like my whole life has been a lie. I apologize to the writers of this script as this world-changing view made it hard to concentrate on any other matter than not duplicateabitable keys.

22 year old Skyler, an aspiring sports agent, is a Duke student who makes a bet with her seven best friends – the main ones being Willa, a lesbian hopeless romantic, Frankie, a super slut, Nisha, a “posh narcissist,” Jules, the “no filter” girl, and Poppy the hippy – that whoever gets married last wins the pot of money.

They’re all going to put in 10 bucks. For some reason, there’s a bracket involved, like a tournament. But it doesn’t really make sense since nobody is actually playing against each other. It’s whoever marries last wins. So that was a little confusing. But anyway, at the last second, they decide to throw the pot of money into this new thing called “bitcoin.”

Cut to 10 or so years later and Skyler, who’s frustrated about still being an agent’s assistant, goes to check the bitcoin pot only to find out it’s now worth 5 million dollars!! She tells her friends and insists that they stick to the competition agreement. No sharing. The only two people left besides Skyler are Willa, who’s way too passive on the dating scene, and Frankie, who has only ever said she’ll marry Tony Hawk.

Thus begins Skyler’s secret plan to speed up Willa’s dating life and somehow convince Tony Hawk, who’s already married, to marry her friend. She figures if she can get this money, she can quit her bigoted agency and start her own company. Meanwhile, Frankie starts secretly hanging out with Skyler’s fiancé, Mark, encouraging him to pop the question to Skyler as soon as possible. Who will win out and force the other to marry first? That is the 5 million dollar question!

This script opens up an interesting discussion about what to do when you’re faced with two different paths for your chosen concept. Because one version of this concept is a fun silly Hollywood comedy. But that’s also the less interesting version of the concept.

The more interesting variation is the dark comedy version where people get nasty when they realize how much money is on the line. Maybe they even start killing each other. Unfortunately, that version is a lot less marketable. Look no further than the difference between Bridesmaids and Bachelorette. Both movies covered bridesmaids in a comedic fashion. But while one was a megahit that became a part of popular culture, the other is nearly forgotten.

However, what you’ll note is that the writer of the dark comedy version of the idea, Leslye Headland, went on to have a cool career that involved making shows like Russian Doll. Her darker comedic voice made her a “cool kid on the block.” And the thing about becoming a Hollywood cool kid is that you always get invited back to the cool kids’ table where you can pitch your latest cool project.

The people who write movies like The Man From Toronto or Me Time don’t get that courtesy. They’re actually some of Hollywood’s most discriminated-against writers (is “comedyist” a thing?) because broad comedy is thought to be the hackiest of all the genres. Then again, you don’t really care about that if you’re clearing 750,000 dollar checks.

In the end, you have to decide what is more organic to you. What are you better at? Also, what do you want to be? Do you want to make fluff yet buy a house in Hancock Park? Michael Bay once famously said, “I make movies so I can buy Ferraris.” If you want to be that kind of screenwriter, I have NO QUALMS with that. But you have to be willing to sacrifice some artistic integrity and be okay with a few sneers when you walk past the cool kids table.

Okay, about the script.

It’s working under a problematic structure – namely, it’s being dictated by a negative goal, and negative goals are hard to pull off. What’s the difference between a negative and positive goal? Well, a positive goal would be that all these girls are trying to get married as fast as possible because the first person who gets married wins the money.

That’s not this movie, though.

Each person is trying to AVOID getting married. That’s a negative goal. Now, why would that be a writing problem? Because it’s easy to not do something. You just don’t do it! It’s simply not as compelling as doing something. Also, negative goals are really bad at pushing the plot forward.

Today’s writers try to circumvent this with some sleight of hand. The negative goal is turned into a positive goal by having Skyler try and get her unmarried friends married. So now Skyler technically has a positive goal that makes her active. But it still doesn’t solve the issue that Skyler, herself, doesn’t need to get married. So then where’s the drama? Where’s the suspense? I suppose that by Skyler being active and getting her friends married, she receives the money faster. But I don’t know if I care about that. I mean am I really going to be in the theater, on the edge of my seat, saying, “Oh man! I really want Skyler to win this money as soon as possible!”

You know how when a writer uses a double negative in a sentence, we, the reader, have that hiccup while reading it? It takes you an extra second to understand the meaning of the sentence. That’s this script in a nutshell. You constantly have to remind yourself why people are doing what they’re doing because it’s all reversed. It’s not a clear easy-to-understand goal.

Whenever you have goal issues, you’ll have stakes and urgency issues. Cause your goal dictates your stakes and urgency. There is zero urgency here. The only urgency is Skyler’s impatience. It doesn’t matter if she gets the money today or four years from now, she’s still going to get it.

Even still, the objective we’re after takes so long to complete (a wedding that officially eliminates a contestant) that we don’t feel any tension from the situation. Skyler is trying to find a girlfriend for Willa. Let’s she say she does. Now we have to wait a year for them to get married and we can cross Willa off the list? That’s not how movies work. Movies work in tight timeframes. We’re talking weeks. We’re talking days. That’s the timeframe you want to be working with. Especially in comedy, where things need to move fast.

The writers do display some creativity. For example, the movie starts at a Duke basketball game and the announcers of the game break the 3rd-and-a-half wall and start commentating on our group of girls instead. That then becomes a running theme throughout the movie where sports announcers will narrate the latest developments with the girls.

I like it when writers think outside the box so I appreciate this. But, at the time same, when I see this sort of thing, I tend to think that the writers are trying too hard. Sort of like, “Look at me. I came up with this clever thing. I’m so clever.” Unless it feels soooooo organically ingrained in the writing, I can’t help but label stuff like this “try hard.”

One of these days, I’m going to write an article about where the line is when it comes to acceptable sloppiness in comedy. I think today’s concept is too overbearing and not believable enough. I mean, let’s be honest. Wouldn’t these girls just split the money? They’re all friends. None of them are greedy. So for them to go along with this ancient bet thing feels forced. And if you don’t believe in that premise, nothing in the movie will work, since all the dramatic tension is dependent on you caring about the bet.

But is that my fault? This is comedy. Shouldn’t I loosen my grip a little bit? Why am I being so anal about every part of the script being airtight? Would a family really drive their dead grandma around on the top of their car as they did in National Lampoon’s Vacation? Probably not. And yet that movie is a classic.

But, for me, there’s way more loose than tight here. I’m fine with a little sloppiness in comedies. It can actually help the comedy at times. But if I don’t even believe that what’s happening would happen, it’s hard for me to invest emotionally. And if I’m not invested emotionally, it’s hard for me to laugh. I’ll chuckle. I’ll have a few of those surface-level laughs. But for those deep uncontrollable laughs, the screws have to be way tighter than they are here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The one thing this script gets right is that the money represents something. Money is always a far more effective tool in a screenplay when it represents something important to a character. In this case, we establish Skyler’s desire to get promoted to an agent. That way, when the windfall of money enters the equation, she becomes obsessive about it, because it means she can finally quit her job and start her own agency, something she’s dreamed of since she was a kid.

Genre: Drama (Book)

Premise: Two brilliant college kids take their lifelong love of games and turn it into a successful video game company, only for life to test their company, and them, in ways that neither of them could possibly prepare for.

About:Last year, if you asked anyone with a penchant for reading what book you should read next, 3 out 4 people would’ve told you, “Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow.” Novelist Gabrielle Zevin has been writing books for nearly 2 decades. But none has caught on like this one did. When asked how she came up with the idea, she said that she was in a slump and did what writers do when they’re slumping – procrastinate. Her preferred form of procrastination was video games. But when she found out that her favorite game from her youth, Gold Rush, was no longer available to play, she felt a sense of loss that inspired an idea she encapsulated in just two sentences: “2 video game developers. Their games are their lives.” Zevin never expected in a million years that her offbeat novel would become her most successful one. But something about the characters clicked with readers. It didn’t take long for the book’s success to catch the attention of Hollywood. Paramount snatched the rights off the market for a cool 2 million.

Writer: Gabrielle Zevin

Details: 416 pages

The reason I wanted to review Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow is because it’s the kind of book that’s not supposed to do as well as it did. The books that do well are where some girl is missing, a woman is in a toxic relationship, a concubine is trying to survive in 1820s South Africa, or yet another Holocaust-adjacent story.

There is no proven market for thoughtful stories that span 15 years about video game pals. I like any piece of writing that disproves the narrative so I signed up for Tomorrow x 3. More importantly, when a book or script proves the market wrong, it’s often because the story is amazing. It has to be if it’s going to disprove the trend.

The story starts in the late 1980s in Los Angeles. A young whip-smart girl named Sadie Green is hanging out in the kid’s room at a hospital while her parents tend to her sick sister. It is there where she meets Sam Masur, a weird kid with a severely damaged foot due to a catastrophic car crash that killed his single mom. To pass the time, the two play Super Mario Brothers together and, over the next several months, develop a friendship.

Many years later, when Sam is at Harvard, he runs into Sadie, who’s also going to school out east. “You still play video games?” She asks him. Of course, Sam says. Sadie hands him a disk. “It’s a game I made. Let me know what you think.” Sam goes back to his dorm room where his roommate, Marx (the opposite of Sam in every way – handsome, social, popular) grabs the game and starts playing it. “This is amazing,” he tells Sam.

Sam agrees and gets the wild idea to make a game with Sadie. Over the summer, they create Ichigo, a game about a young child who gets swept out to sea during a tsunami and must somehow make it back to land. The inspired game becomes a sensation and Sam and Sadie are anointed “the next big thing” in video games.

After a not-as-successful sequel, the two head back to their hometown of Los Angeles to start a company with Marx as the CEO. The next game they create is called “Both Sides,” where the main character can switch back and forth between their ordinary mundane life and a heightened intense world where they are a hero. The game is a big enough hit to grow their company.

But the press has a tough time with Sadie and Sam. Despite the two spending every single second together, they are not, nor have they ever been, romantically involved. They’re so flummoxed by their relationship that they eventually give up on trying to make them a thing, instead focusing on Sam’s unique story, which involves his underdog persona brought on by his disfigured foot (Sam must walk around everywhere with a cane).

Eventually, Sadie finds herself being drawn more and more towards Marx, and the two surprise each other by becoming an item. As this is happening, Sam and Sadie’s relationship is deteriorating due to a number of factors (differences in opinion on the company’s direction, Sadie not getting as much credit as Sam from the press, Sadie refusing to make another sequel to Ichigo) and it’s looking like their professional future is in doubt.

(Spoiler but without details) But then something so devastating happens that the two will be forced to reevaluate everything about their friendship, their business, and their lives. Worst of all, this tragedy threatens to destroy the one thing in their lives that they have always been able to turn to when they’ve been down – the simple beauty of getting lost in the brilliant and fun world of video games.

The thing that struck me most about this book was the absence of plot.

It was jarring, at times, how little plot was guiding the story.

The novel, instead, is 98% character. Luckily, it excels in that department. Sam is the most interesting character. At first I thought his broken foot was just a way to get him in the same hospital as Sadie so the author could start their friendship.

But Sam’s foot is its own storyline. Maybe that’s a lesson right off the bat when it comes to plotless stories. Utilize storylines within the character’s life that can become their own pseudo-plots. His foot situation is so complicated that it gets worse and worse over the years until he finally has to amputate it. That alone was a tough pill to swallow. Cause you could see how much it shaped his view of the world.

Another thing about Sam is that he’s asexual. I can’t remember if I’ve ever read a story with an asexual main character. I’ve read every sexuality under the sun, especially over these last few years (homosexual, bisexual, demisexual, pansexual). But asexual? That’s a new one. And it helped make both Sam, and Sam’s relationship with Sadie, wholly unique.

Sadie isn’t as interesting as Sam – she’s basically a poor kid in rich kids shoes – but there’s a certain defiance of conventional thought in her that makes her fun to try and figure out. She shouldn’t be the kind of person who befriends a kid like Sam. And yet she does. And it helps that we’re always trying to figure out, despite their identities (he’s asexual, she sees their relationship as a loving friendship only) if they’re going to get together.

Then you have Marx, a dude who’s incredibly good-looking and charming and gets tons of girls because of it. But he doesn’t have any of the talent Sam or Sadie has. So he’s sort of like the perfect stick in their mud. His presence adds an unpredictable dynamic to the OG friendship that’s fun to speculate on. “Will Marx go for Sadie?” is a question we’re asking almost immediately.

It’s amazing that Zevin is able to get so many pages out of just these three characters doing nothing. I say “nothing” while laughing to myself because I know they’re making video games and growing their company. But the game development in the book becomes repetitive. They just made a game. So making another one isn’t exactly compelling to read. Yet we enjoy seeing how this trio deals with the challenges that come with success.

(Spoilers from here on out) Maybe the reason this book did so well is that their success never feels cliched. This isn’t like a music biopic where you see a singer become famous out of nowhere then stumble into drug use and excess. That’s not this story. Their success is more up and down, which more appropriately mirrors real life. So it feels authentic.

But the main reason I think this book is so popular is because the guy and the girl don’t get together. Think back through novel and movie history when you’ve had a story where the guy and the girl don’t get together at the end. I’m not talking because one has to go to war. Or because outside factors forced them apart. I’m talking about they just don’t get together. Even though they could. I don’t know if it’s ever happened.

So you’re reading this book all the way up to the very last page hoping that it’s finally going to happen. And it doesn’t! It’s so unexpected. It goes to show that if you want to write something that breaks out, you will have to make at least one bold creative choice, the kind of choice that all the books and teachers would tell you never to do.

I have no doubt that when Zevin sent this book out to her friends for notes, they said, “You have to have Sadie and Sam get together!” It’s just not done that you write a book about a girl and a boy over the course of 15 years and there’s never a single romantic moment between them. It’s crazy. And yet I have no doubt that it’s a major reason why this book is such a hit.

Now, I don’t know what Zevin was thinking when she signed on to make this a movie. Maybe she was thinking, “I want a new house.” But this is not a movie. Not in a million years is it a movie. It’s so emphatically a TV show. It’s kind of like the anti-Normal People. That show was about a guy and girl who get into a years-long drawn out sexual and, at times, meaningful relationship. This is about a guy and a girl who get into a years-long drawn out friendship.

TV is character. This novel is character. But we’ll see. It’s such a beloved novel that I’m sure they’ll do everything in their power to make the movie as good as it can be (Zevin is writing the screenplay so she can stay true to her vision). But this could easily be a TV show, and not just a limited one. You could follow these two and their unique friendship for years if need be.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow is, at times, difficult to read. The conventions you’re used to never arrive, leaving you frustrated. But once you’re able to finish the book and see the entire canvas, you realize how good it actually is.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t get down if your latest script was a dud! Your next screenplay could be the one that launches you into the stratosphere. Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow has sold over 1 million copies. But you know how many copies Zevin’s previous book sold? “Young Jane Young,” about a congressional intern who’s publicly shamed for having an affair with her boss (arguably the more marketable concept), sold just 10,000 copies. Just need to find that idea that pops!

Today, Thursday, is the last day to send in your logline for the Halloween Logline Showdown. If you have a great horror script, get that logline in! I’m determined to find a great horror screenplay before this Halloween month is over.

What: Halloween Logline Showdown

Send me: Logline for either your Horror or Thriller script (Pilot scripts are okay!)

I need: The title, genre, and logline

Also: Your script must be written because I’ll be reviewing the winning entry the following week

When: Deadline is Thursday, October 19th, by 10:00pm Pacific Time

Send entries to: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

So what will I be looking for when I review the winning horror script next week?

To answer that question, we need to understand why writing a horror script is so tricky. Horror is one of those genres that’s primarily director-driven. Case in point, when was the last time you heard of a great horror screenwriter? Yet you know the names of John Carpenter, Wes Craven, James Wan, George Romeo, and the list goes on. The only horror screenwriters you’ve heard of are the ones who direct.

I’m not trying to scare you. I’m only saying that writing a good horror script is a bit like cooking a pizza. We all know what makes a good pizza. Great crust, lots of cheese, a delicious tomato sauce. And yet when we try to make pizza, it’s a far cry from what we eat at the restaurant.

So what I thought I’d do is provide you with the ten things that I find most important in a horror script, starting with the most important and ending with the least important. Let’s get into it.

One – It’s got to have three scary-AF scenes – Nothing else matters in your horror script if it’s not scary. And the place you scare people the most is in your set pieces – the big featured scenes in your script. I’m talking about the girl emerging from the well in The Ring, the “Do you like scary movies” opening scene from Scream, the sister decapitation from Hereditary. You need three of these in your horror script. These are so important that even if you have a terrible screenplay, there’s a good chance that by including these three great horror scenes, someone will want to make your movie. Because a truly scary scene can live on forever regardless of the quality of the movie (see the hospital scene in Exorcist 3). Producers know this. So use all your time to come up with these scenes.

Two – This is an extension of number one. You must draw your scares from what’s unique about your script. One of the biggest problems with horror movies is that they’re all cliche. Everybody uses the same ten scares (creepy dream sequence, someone behind you in the bathroom mirror, the injured woman running away from the killer, etc). The best way to avoid this is to utilize what’s unique about your concept because those scenes are less likely to be in other people’s horror films. A great example of this is the foot-breaking scene in Misery. Annie is obsessed with this man. She’s imprisoned him in her house. He tries to escape. So, in order to make sure he doesn’t try again, she violently breaks his feet with a hammer. That scene is very specific to that situation. Whereas, if you’re writing a cat jumping out of a cabinet, that’s a scene that can literally be in any horror movie. If your horror scene could be in any horror movie, DON’T INCLUDE IT!!!

Three – Strong Characters – I’m going to drop a controversial Carson-bomb here. But I think character development in horror films can go too far. The Babadook is a good example. I liked The Babadook. It’s a solid movie. But it places so much emphasis on character development that it ends up overshadowing the horror. That movie is 70% drama and 30% horror. Whereas a good horror movie should be 70% horror and 30% drama. With that said, too many writers make the mistake of putting nothing into their horror characters. This is a script-destroying move because if your horror characters are too thin, we won’t be afraid for them when they’re in scary situations. And having the audience care for your characters when they’re in danger is the whole ball of wax when it comes to horror. The reason horror works is because we sympathize with the characters! Therefore, when they’re in danger, we feel like we’re in danger. So make sure we like the characters, we care about them, they’re going through something internally (struggling with self-acceptance, for example) as well as externally (they’re getting bullied at school). They have some sort of unresolved relationship with another character. And that’s it. Keep it simple.

Four – A killer (terrifying) monster/villain – For a lot of horror films, the monster is the concept (Mama, Freddy Kreuger, Pennywise, Slotherhouse). So you want to spend a significant amount of time coming up with your monster. Not to mention, a great monster takes care of the marketing all by himself. Just look at The Nun. All you have to do is put the Nun’s face on a poster and you’re finished. To find your horror script’s monster, I suggest you look to the past. Look up monsters and scary stories from all parts of the world throughout time and you’ll find some really gnarly things. I’ve found that building your horror monster from the ground up (figure out their past and let it inform their present) works better than trying to come up with a scary image (a clown with no eyes) then trying to retroactively shape their origin. But that’s just me.

Five – Be shocking – This is a bit controversial as I know not everyone will agree with me. But I read enough scripts to know that if you don’t do anything above and beyond the usual, it’s likely your script will be forgotten. And with horror, the way to be remembered is to be shocking. As someone brought up the other day, the girl in The Exorcist has a scene where she stabs herself in the vagina with a crucifix. How do you not leave that script never forgetting that moment? And if you doubt that, ask yourself, who is the most talked about horror director at the moment? It’s Ari Aster. And that’s Ari’s whole strategy. He shocks you. Look up his first short film if you don’t believe me. To shock readers, you have to be willing to write about things that make you uncomfortable. But I promise you if you shock us, as long as it’s organic to your story, you’re going to leave an impression.

Six – A unique setting – Again, what you have to remember is that horror is the most ubiquitous genre there is. You’re competing against more scripts than in any other genre by far. So you need to look for any way you can to separate your script from their scripts. The setting is a great way to do this. Because if you can come up with a unique setting, you won’t be operating in the same locations and situations as all the writers before you, which will give you new avenues to find unique scares. “The Thing” is a great example of this. It’s not set in a cabin in the woods like 10 million other horror scripts. It’s set on a remote base in Antarctica. That immediately gives it opportunities to find fresh scares.

Seven – Effort – You might be noticing a theme here. Horror scripts get swallowed up in cliche for a number of reasons. To combat this, you need to exhibit outsized effort when venturing into this genre, something very few writers do. You are not going to be able to zip through the writing process of a horror script and write something good. I guarantee your script will be littered with cliches if you do. You need 7, 8, 9, 10 drafts to weed out all the familiar stuff and add those deeper more imaginative ideas that come from having a high bar and pushing your creative limits. You should be treating your horror script like Martin Scorsese treated his Killers of the Flower Moon script. He did not stop rewriting until he found something he liked.

Eight – Build tension slowly – A lot of great horror does not come from the act of the [scary thing] jumping out at you. It comes from the build-up to that moment. So, when it’s applicable, cue the reader that a scary moment is coming then draw out the lead-up to that scare for as long as possible. If there’s something in the corner of the dark bedroom, for example, don’t have it scurry over right away. Have your character try to make out its features, unsure of it’s a monster or just clothing, have them turn on their lamp only to see that there’s nothing there. Have them turn the lamp back off and turn over to go to sleep. But then they hear a skittering and shoot back up, looking around. There, in the other corner… is that a body? Are my eyes playing tricks on me ? You get the idea. The lead-up is what super-charges the scare.

Nine – Concept is nice, but not essential – In my experience, a horror script does not have to have a great concept. This is because horror is the only example where the genre itself is the concept. People come to horror movies to be scared. So as long as your trailer looks scary, you’re good. A scary nun. A scary doll. A haunted house. An invisible evil husband. Taking your boyfriend home to meet the weird parents. A girl is possessed. A spooky entity follows you around. Zombies. More zombies. Lots and lots of zombies. This is not to say a clever horror concept (The Sixth Sense) is bad. Quite the opposite. If you can come up with a great concept in the horror genre, you’re unstoppable. But you don’t NEED a great concept to write a good horror script.

Ten – Plot don’t matter as much as you think it does – I want to be clear when I say, you would like to have a solid plot in your horror script. But it’s not mandatory. We know this because nobody has ever watched a horror film in their lives and come out saying, “Man, I loved that plot.” It’s just not a part of the genre’s lexicon. I told you last year when I watched Friday the 13th for the first time in two decades how shocked I was at the lack of any noticeable structure. It was just a barely-cobbled together string of scenes where a killer tried to kill teenagers at a camp. And that went on to become a half a billion dollar franchise. Again, if you have a great plot – AWESOME. It’s only going to help your horror screenplay. But you should be spending more of your time on scary set pieces and likable characters than an amazing plot.

DEALS DEALS DEALS! – I’m offering a $150 discount on both my feature script consultations and pilot script consultations. I’m also offering a 3-pack of logline consultations for just $50! If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and mention this article!

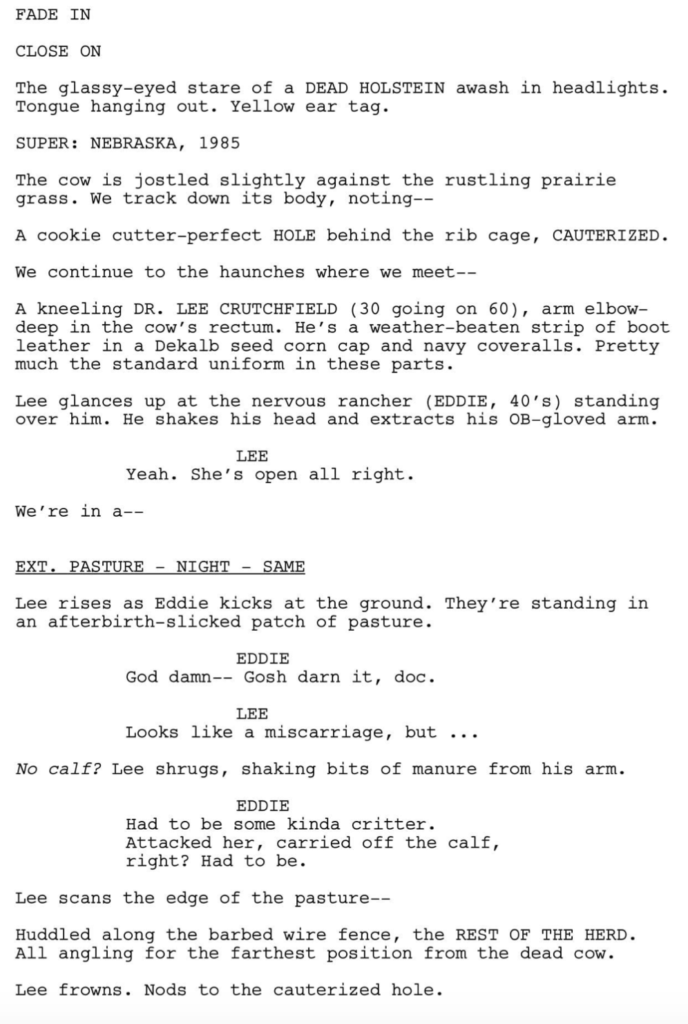

Genre: Sci-Fi/Horror/Drama

Premise: Amid a rash of cattle mutilations in the ‘80s, a rural veterinarian holds an alien captive with the desperate hope that its miraculous healing biology can save his terminally ill wife.

About: This is the runner-up in the First Page Showdown. If you’re wondering why we’re reviewing the runner-up and not the winner, it’s a long complicated story but the gist of it is, the winner hadn’t finished his script yet and so we’re waiting on that before we can review it. Actually, that wasn’t long or complicated. It was pretty straightforward. Okay, let’s get to the review. Oh! And remember that we have Halloween Logline Showdown coming up next week. Get those loglines in!

Writer: Mark James

Details: 94 pages

Here’s the first page if you want to reacquaint yourself with it.

Lucky us.

We got a horror script just a week before Halloween Showdown! Sometimes the script gods shine down on us.

BUT!

The script still needs to be good. And the whole reason I picked this first page to compete was because it felt like a different kind of alien movie.

Let’s see if my instincts were right.

The year is 1985. We’re in Nebraska. We meet 30 year-old Dr. Lee Crutchfield as he is elbow deep inside of a dead cow’s rectum. Lee is a vet and although he’s seen a lot, this is not a normal Tuesday night for him. This is actually quite rare.

Word on the street is that cows from all over the local area have been getting mutilated. But Lee’s not buying it. He thinks an animal did this and is vindicated when a rabid badger pops up and he shoots it dead. He tells the rancher he has nothing to worry about, grabs the dead badger and heads back to the clinic to do tests.

Before he does that, though, he heads over to the hospital to see his late 20-s wife, Blair (who he calls “Mother Bear”), who has some sort of weird disease that causes dementia. Her situation is getting worse by the day but Lee is not giving up.

Back at the clinic, Lee spots the dead badger levitating, only to realize it’s being shuttled away by a cloaked 8 foot alien. Lee is able to neutralize the alien with a cattle prod and chain it up. Although the alien is coy at first, it eventually comes clean regarding having the magical ability to cure.

While all this is happening, an Omaha FBI agent named Annabelle Sable shows up who seems to have some knowledge about these aliens. She tells Lee that these off-worlders are not to be trusted! Everything they say is a lie. But all Lee hears is “healing.” So when his wife goes into a coma, Lee decides he’s using the alien cure to save her. But at what cost? And what happens if it doesn’t work?

I had a lot of thoughts swimming through my brain when I finished this script. I knew I could take the review in a familiar direction.

But since this all started with a First Page contest, the question that seemed the most relevant was, “Did I get the script I expected to get from the first page?”

The answer is no.

That’s not a bad thing. It’s just that when I read that first page, I imagined this thoughtful interesting take on aliens where the writer approached things from an angle that we hadn’t seen before. Cause this is a movie about aliens. And most movies about aliens start out with an on-the-nose scene that screams from the mountaintops that the movie is about aliens (i.e. a spaceship in the sky).

By approaching it via a dead cow’s rectum, you told us that this was going to be a different kind of journey (not unlike how we started in Adam Sandler’s rectum in Uncut Gems and got a totally different movie).

And while I suppose you could argue the script does turn out to be different, it ended up feeling too familiar when it was all said and done.

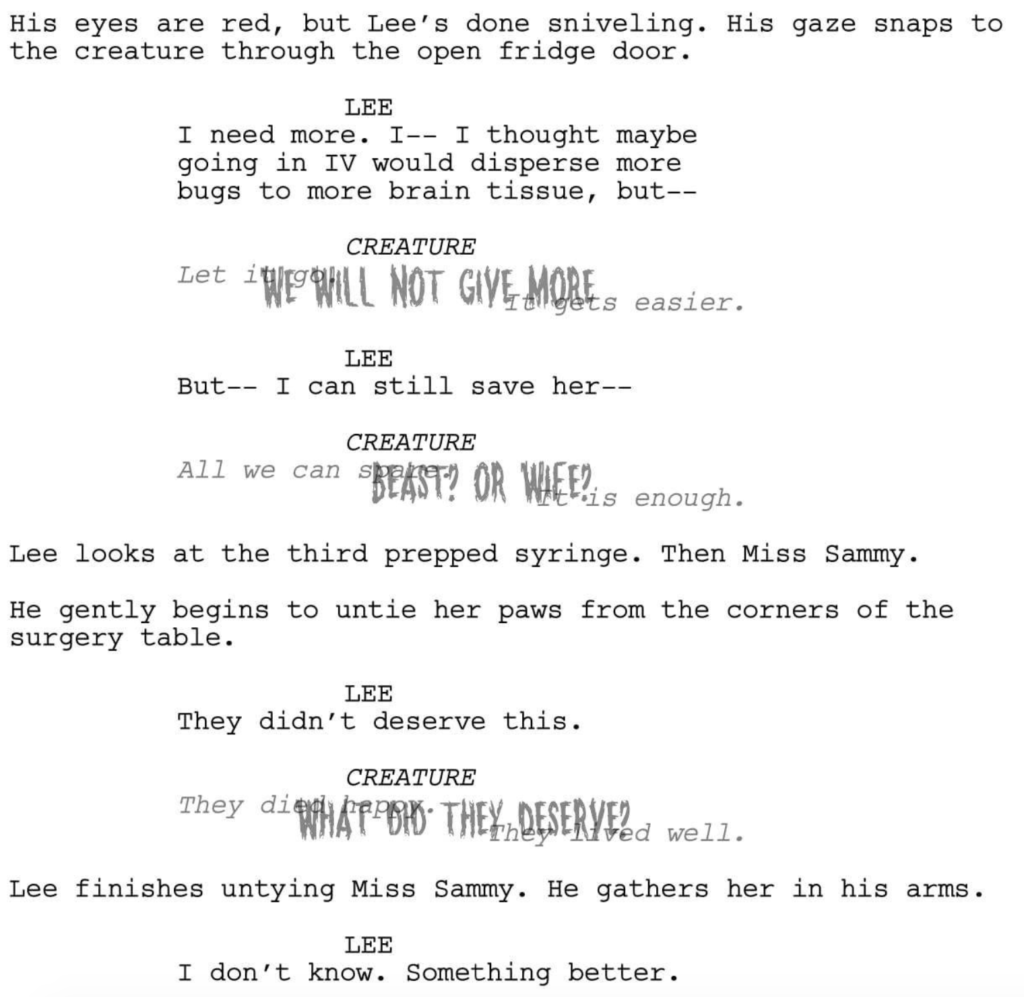

To the writer’s credit, he takes creative risks, the most visual being the alien’s dialogue. This is how all the alien dialogue looks:

What I liked about this choice was that an alien is going to look weird. It’s going to look different. This dialogue style captured that difference in a visual way. When we saw how different it was from normal dialogue, we subconsciously imagined the alien. Which was cool.

But the dialogue was hard to read. The middle part often covered the regular text on either side, which meant I had to squint and move the page around to see what the alien was saying. James also fades the regular text out as the script goes on until it’s practically invisible. So I wasn’t sure if that text even mattered?

Finally, I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to interpret the dialogue. The middle section always contradicted the ends so… I guess that meant the alien was always lying. But it’s still spoken dialogue so didn’t that mean Lee could hear it? All in all, as creative as it was, I felt it was more trouble than it was worth.

The script’s strongest suit is its emotional core – the relationship between Lee and Blair. But I’ll be honest, I had trouble giving in to it. For starters, they’re both late 20s, early 30s. And Blair has dementia. It didn’t read right. A 28 year old with dementia? I’m sure it happens but it happens rarely enough that it creates that dreaded “reading hiccup.” And then the characters called each other Mama Bear and Papa Bear, the kind of nicknames old people use for each other, which confused me, because these characters were young. It just created this clunky vibe to the proceedings that prohibited me from fully enjoying what I was reading.

And while I don’t mean to pile on, this script doesn’t resolve my belief that you can make aliens scary in the way that you can make traditional earthbound creatures and monsters scary.

What happens in The Harvester – and what happens in a lot of these scripts that try to combine horror and aliens – is that, at a certain point, the writer learns that making them scary doesn’t make sense. So it always turns out the the alien is helpful instead of hurtful. We see that here with the alien offering his magical medicine that can heal anything. And, at that point, what are we scared of? We’re not. In retrospect, I’m not sure I was ever scared. And I’m someone who routinely watches scary movies through my fingers.

I mean how scary of an alien can you be when you’re easily restrained by handcuffs? It just didn’t make sense. And I don’t want to dog James because I’ve been down this road before myself. With my own alien-horror scripts which ran into this same problem, and with scripts from other writers that I’ve tried to shepherd. But none of them can ever quite figure out this “aliens being scary” thing. You can do it in flashes. But over the course of the story, it doesn’t make sense for aliens to be scary. Why come 100 light years if you’re going to hide underneath beds and say “boo?”

Overall, as hard as I tried, I couldn’t connect with this script. The horror wasn’t horrifying enough. The sci-fi hit a wall. And the drama was affected by little choices that resulted in an unnecessarily clunky relationship journey.

It wasn’t for me but I’m curious what all of you think. Check out the script below.

Script link: The Harvester

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whenever I see a writer offer three genres for their script, the first thing I think is, “This writer doesn’t know what kind of story he’s telling.” And that’s how I felt when I read this. “I’m not sure this script knows what it wants to be.” It leans most heavily into the drama side of things. That’s when it’s most comfortable. Cause I think James understood that storyline the best. But this alien who’s sort of dangerous but not really dangerous dictating the majority of the narrative had me scratching my head. It just felt like there was a better story that could be told here. And my gut tells me simplifying the genre is a good place to start.

The other day, I was engaged in an e-mail exchange with a professional screenwriter with high-level studio credits so I was curious what they thought about Oppenheimer.

I’ve been curious what a lot of people think about Oppenheimer not just because it’s the movie du jour. But because I’m less than impressed with Christopher Nolan’s writing. I don’t know if it’s because he’s still using Final Draft 2 or if he writes his scripts in notebooks like Tarantino then runs out of space therefore can’t rewrite. Whatever the case, we can all agree his writing is inferior to his directing.

Yet it’s hard to argue with both a 97% critic and 96% audience score. So I’m wrestling with this contrary opinion of mine, even if I’ve been running into more and more people who I share secret whispered conversations with about their dislike of Oppenheimer. These Oppenhaters point out the same problems I had with the movie. It’s long. It’s messy. It’s unfocused. The multiple timelines hurt more than help.

Here’s what the writer said in their e-mail…

Regarding Oppenheimer, I genuinely, unequivocally, passionately detested it. I thought the first hour played like a trailer. There was no scene work. I hated the bombastic score meant to cover up the sh—y writing and act as collagen throughout the film. I was bored and confused for the entire second half (or 3rd act, or whatever you want to call it since the movie is so absurdly disjointed).

Arguably the most important beat in the film – the moment in which Oppenheimer chooses to build the bomb – was not articulated in the slightest. I am not saying it should have been this crazy exploration of how he got the “lightbulb” moment. But even a slow push-in as he studies his rivals’ equations or something would have worked. Another thing I don’t f—ing understand: Downey Jr giving interviews in which he praises Nolan’s direction, saying that he, Nolan, compared ‘Oppenheimer and Strauss’ to ‘Mozart and Salieri’ and Downey was like “ah! Yes! Now I know how to play it”. WHERE WAS THAT DYNAMIC IN THE FILM? It was completely non-existent.

They make several points I agree with.

I, too, thought the first hour was constructed strangely. I wondered why we weren’t getting any actual scenes. It was pasted together almost like a montage, or, as the writer said, a “trailer.” Think about the scene in The Dark Knight where The Joker shows up at the bad guys’ meeting and imposes his plan to take down Batman. That’s a scene. Why didn’t we get anything like that in Oppenheimer?

I’m also right with this writer on their “absurdly disjointed” comment. We seemed to be bouncing back and forth between timelines with no clear purpose or logic. It felt random. Watching that, knowing that audiences bought into it whole-cloth, has me utterly confused. Am I expecting too much here? Am I over-analyzing? Or do I just not gel with Nolan’s storytelling style?

There was an argument in the comments section of my Oppenheimer review pushing back on my frustrations with the third act. My belief was that the movie was over once the bomb dropped. “Why are we still here?” Oppenlovers pointed out that the movie was called “Oppenheimer,” not “The Making of the Atomic Bomb.” Therefore, it made sense to stay with Oppenheimer 45 extra minutes after the bomb had been dropped. We hadn’t yet concluded *his* story, was the argument.

But here’s my pushback. If “Oppenheimer” was more about Oppenheimer than the making of the atomic bomb, how is it that I still don’t have a great sense of who Oppenheimer was as a person?? If I asked you to tell me who Oppenheimer was after seeing this movie, would you be able to easily do so? Or would you stumble around and throw a bunch of adjectives at me and expect me to make sense of it myself? Cause I’m guessing you would do the latter.

When I watch The Wolf of Wall Street, I know Jordan Belfort was a man done in by his insatiable appetite for excess. When I watch Taxi Driver, I know Travis Bickle was a man done in by his intense loneliness and isolation. I know this because the writers hit on those flaws again and again and again. They wanted the audience to understand their protagonist intimately. I don’t know what I’ve learned about Oppenheimer after watching this film. That he really liked physics, sometimes almost kills professors, and gets involved with bats—t crazy chicks?

In my newsletter review of “Armored” yesterday, I talked about connecting the character’s internal life with the plot and how bad writers never make that connection. That’s exactly how I felt watching Oppenheimer. What issues in Oppenheimer’s tumultuous family life bled into his job? Where were the parallels?

A primary character flaw is all-encompassing. It stretches across all aspects of your life. In the Oscar-winning screenplay, Promising Young Woman, the main character, Cassie, is consumed by revenge. It informs every nook and cranny of her existence. For that reason, we know exactly who that character is. Can you tell me the same about Oppenheimer? Do you “get” him as well as you get that character? If you say “yes” I say you’re lying. I say that the only reason you feel like you have a sense of this character is because his name is in the title.

And by the way, I’m not trying to crap on this movie. I’m trying to understand it. I’m trying to understand what others saw that I didn’t. Cause there’s a part of me that thinks people are falling for the Nolan effect. Oppenheimer is an extremely pretty movie. It’s got movie stars for days. The attention to detail is insane. It’s got this, almost, old Hollywood feel that makes it shine in a way that other movies don’t. But, in the end, isn’t it just a beautifully directed film? Does anyone come out of this movie feeling emotion? If so, what was that emotion? I’m curious. Cause I felt way more emotion watching the first act of The Flash.

Obviously, something works in the film. This movie might end up becoming Nolan’s most successful movie ever. So I ask you, what am I missing? What is it that I’m not seeing? I truly want to know. One of my favorite movies ever is Terrance Malick’s The Thin Red Line. That movie does not stand up to narrative scrutiny. It is an uneven plotless experiment. But the cinematography is gorgeous. The score is amazing. The acting is incredible. There’s a realness to the way the film is shot that makes it feel like you really are in the middle of a war. So maybe that’s what people are feeling here? It’s more of a feeling they get while watching this movie? Help me. Help me understand why I don’t see the genius in Oppenheimer. Be as harsh as you want!