Genre: Comedy

Premise: When ghosts take over New York City, a team of female scientists with a strict, “No men allowed” policy, must figure out a way to control the supernatural outbreak.

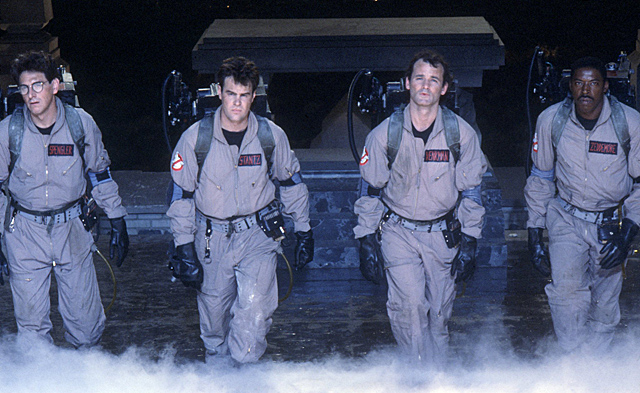

About: One of the most storied project developments in cinema history. 30 years of trying to get a third Ghostbusters made. There have been numerous scripts written by an endless line of writers. Bill Murray refused to read any of the scripts for some reason, preventing the project from ever moving forward. Eventually, a “young corps of Ghostbusters” idea was thrown onto the table. But Sony strangely split that plan into two separate scripts taking two separate angles on the idea. That led to even more confusion and frustration and never went anywhere. A few years ago, Paul Feig (Bridesmaids, The Heat) felt that he could bring something new to the franchise with an all-female cast. Desperation reared its ugly head, the studio greenlighted the film before Feig could change his mind, and for the last two years, the internet attacked the odd angled remake, culminating in a Youtube war where the Ghostbusters trailer became the most disliked trailer of all time. The film finally came out this weekend. Time to figure out how it was received!

Writers: Katie Dippold & Paul Feig (based on the film, “Ghostbusters” written by Dan Akroyd and Harold Ramis and directed by Ivan Reitman).

Details: 116 minutes long

Oh man. Ghostbusters.

After all these attempts. After all these scripts. After all the Dan Akroyd interviews promising another Ghostbusters.

And we’re finally here, 30 years later, a finished product in hand.

I’m sure you’re asking the same question as I.

Was it worth the wait???

The answer can be found in Ghostbusters’ opening weekend take: $45 million.

I think that says it all, right? 45 million dollars. It’s not exactly a bust. It’s not exactly a hit. It just “is.” And that’s the best way to describe the new Ghostbusters. It just “is.”

So what happened? How did this film end up in box office purgatory, critical consensus purgatory, audience consensus purgatory?

I’ll tell you how. Because nobody involved wanted to make it.

Including the most important person on the project – THE DIRECTOR! That’s right. Paul Feig turned this down. He only later agreed to do it so he could get back together with his girl posse. And thus this passionless project was born.

Contrast this with the original Ghostbusters. Have you read any of the interviews from that time? Dan Akroyd was OBSESSED with this idea. He was PASSIONATE about this idea. This was his baby. And that’s the biggest difference between the original and this alternate universe version.

Passion.

I mean when you see Akroyd excitedly sliding down that pole in the original, that’s genuine excitement! His eyes tell us everything: “Can you believe we’re making this!?”

There isn’t a single person on this cast or behind the camera that would slide down a pole for this movie. And that’s why we have a lame Ghostbusters. When you walk out of the film thinking, “Something was missing and I can’t put my finger on what.” THAT’S the “what.”

And that’s the real reason behind the blowback. The Ghostbusters people want to paint it as misogyny because it’s the narrative that favors them. But the reality is, this movie got greenlit to take advantage of a hot trend – comedies centered around females. NOT because someone who loved and cared about Ghostbusters wanted to share it with the world.

Now you may reply with, “Wait, Carson. What about Star Wars. Didn’t they do the same thing with that movie? Wasn’t that all about the money?” One big difference. They hired people WHO CARED about Star Wars. Who would’ve made it for free. Who would’ve given up their first born to direct a Star Wars movie. That’s not the case with this Ghostbusters reboot and everybody involved knows it.

Find me one interview in the past 20 years of Kristin Wiig or Melissa McCarthy or Paul Feig citing Ghostbusters as an inspiration. You won’t find it. I’d be willing to bet Wiig only did this franchise as a favor to Feig for jump-starting her career.

By this point you’re probably desperate to know what this movie is about. And by “desperate” I mean you couldn’t care less. Too bad. I’m going to tell you anyway. A group of scientists with an interest in the paranormal hear that real ghosts are invading the city and start a business (Ghostbusters) to capture those ghosts.

The difference between this and the original is that instead of our three Ghostbusters being buddies, core members Erin (Kristen Wiig) and Abby (Melissa McCarthy) USED to be friends, and don’t get along anymore. They’ve also added a street-wise expert on New York City (Leslie Jones) and the lamest villain this side of a Saturday morning cartoon.

Despite the overall lameness of the movie, as far as screenwriting goes, there are some things worth talking about, starting with that broken friendship.

When I went back to watch the original Ghostbusters, a movie that came out before there was a single screenwriting book on the market, I noticed there weren’t any issues with the friends. They were one big happy unit.

Whereas Ghostbusters 2016 was made during a time when there are 100+ screenwriting books on the market (mine included) drilling into your head that you have to explore characters, explore characters, EXPLORE CHARACTERS. Hence, in this new modern Ghostbusters, we have a broken relationship at the center of the film.

So the question becomes, has this newfound obsession with conflict-heavy relationships made storytelling better or worse? Are we overthinking our screenplays when it’s clear, from the original Ghostbusters’ success, that eschewing character development, at least in some cases, results in a better film?

The answer to this is complicated. Good character development always trumps good non-character development. But if your character development is uninspired, hackneyed, or lazy, than the script would’ve been better off without it. And that’s how I feel here. The Erin and Abby riff wasn’t bad. But there’s a definite “Screenwriting 101” vibe to it, as if the script needed to be approved by a USC professor before Sony could read it.

A bigger issue here is the lack of economic storytelling. Feig seems to come from the Judd Apatow school of directing, which is to say, the more, the better. But movies, especially comedies, always work best when the story is streamlined and all of the fat is stripped away.

I can point to a couple of examples for you. In the original Ghostbusters, the secretary is just there answering phones one day. She doesn’t get some grand entrance or interview. That would’ve slowed the story down. This allows us to move through that section of the story quickly.

In the new Ghostbusters, they stop the plot cold to add an interview scene for Chris Hemsworth’s character. Now is this scene a crime against screenwriting? No. I’m not saying never write an interview scene. In fact, I bet they even shot one for the original Ghostbusters secretary.

But here’s the difference. If they did shoot that scene in the original, they cut it. Feig, on the other hand, more concerned with a couple extra jokes, kept his unnecessary scene intact. And it was choices like this – keeping unnecessary scenes around instead of deleting them – that slowed this movie to a crawl.

A more blatant example of this occurs near the middle of the film. We get this weird back-alley “test out our new Ghostbusters weapons” scene. The scene has the requisite number of explosions, prat falls, and variations of “Oh snap.” And the scene is, at best, okay.

BUT IT DOESN’T PUSH THE STORY FORWARD!

Here we are, in the middle of the script. The story has already slowed to a crawl. The audience is getting bored. And you place a scene in the movie that has NOTHING TO DO with the story. It’s just characters goofing around. That’s a screenwriting sin right there. And for neither Feig or Dippold to realize this and cut the scene out, proves why this film was doomed.

It goes back to passion. When there’s no passion, you don’t care about getting it perfect. You care about goofing around and having fun on set. A director passionate about this material would’ve known that that scene wasn’t necessary.

And then there are things beyond the script that irk me. Like Paul Feig talking about Chris Hemsworth. When asked by Deadline what he thought of Hemsworth, this is what he said: “Without hyperbole, I think he’s the next Cary Grant, if he continues on the comedy route.” I mean, seriously? Give me a fucking break. At BEST Chris Hemsworth was an above-average surprise. Cary fucking Grant? Right. And Melissa McCarthy is the next Audrey Hepburn.

This is desperate over-selling, which tells you just how little confidence Feig has in his product. And I think if you strapped Feig to a lie detector and asked him if he could do it all over again, would he have made this movie, he’d tell you unequivocally, no. Which is ironic. Since it doesn’t feel like a new Ghostbusters has been made anyway.

Who you gonna call? Amy Pascal. To tell her this franchise is dead.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Reverse dynamics. This works well in comedy. What you do is you write a scene where one character is very dominant and the other submissive. Then, later in the script, you find a way to reverse their roles and play the scene over again. So in the original Ghostbusters, Venkman (Bill Murray) comes over to Dana’s (Sigourney Weaver) place to look for ghosts, but he’s really trying to make a move on her. She’s disgusted by him and eventually kicks him out. Later on, Venkman comes over again, but this time Dana is possessed by Gozer, who desperately wants to have sex with a human. So now it’s Dana who’s putting the moves on Venkman and Venkman’s resisting. We never get anything close to this clever in the 2016 Ghostbusters, of course.

I am so mad at Disney right now for leading me on all week with the promise of a new Star Wars trailer only to give me some lame behind the scenes crap. Behind the scenes clips are exclusively for DVDs as extra material when you’ve already seen the film five times and there’s literally nothing new left to learn and you’re bored so you remember, “Oh yeah, there’s those behind the scenes featurettes. Let’s check those out.” And then you watch them and you’re like, “Eh, that was kind of cool. George Lucas grew another chin.” They are NOT meant as a primary piece of entertainment to get people excited for a movie. So Disney? SCREW YOU! And Mickey. And Goofy. And Elsa. But not Officer Hopps. I still love her. And if the new trailer is up by the time I wake up, then yes, I will forgive you. But until then, SCREW YOU!

Oh yeah, Showdown Saturday below. Read the scripts and vote for your favorite in the comments section! Winner gets a snazzy Friday review!!!

Title: Defend The Point

Genre: Thriller

Logline: 18 year old Kevin Crutchfield is having a hard time adjusting to his first year at West Point in upstate New York. He better shape up quick; a group of terrorists are on their way to webcast a massacre at the prestigious military academy.

Why you should read: Hello again, writer of Drone here. Let’s see… what did Carson think about Drone( that’s right I read your stupid ass newsletter) and I’m paraphrasing… “I think I’d prefer getting killed by a drone to watching that movie”. What a dick you are huh? Anyway, under the crushing disappointment of yet another contest where I have to pull on my bridesmaid’s dress I began to get angry. That anger led to drinking. And then more drinks. And then a bunch of drinks after that. A month and some days passed and I came out of a blackout with this script. It’s an angry script. Watching the news and seeing all the atrocities playing out across the world was very frustrating. I think a lot of that got put into the screenplay. If Inglorious Basterds was Tarantino’s revenge fantasy on Nazis, this is mine for the assholes who kill people on a whim. Hope you like it.

And yeah I know it’s long… whatever….fuck you.

Title: Red Light

Genre: Horror/Slasher

Logline: After their friends run a supposedly haunted red light and suffer horrible deaths, three disbelieving teens run the same red light to dispel small town superstition, only to find themselves the next targets of a sinister figure hellbent on revenge.

Why you should read: I’ve been teaching Pre-Kindergarten for seven years now, so trust me — I know horror.

Besides wanting to bring the slasher film back for the Z Generation, I’ve always wanted to write a movie that made an ordinary thing seem terrifying. Think of what Jaws did for going swimming, or Shallow Hal for, uh, going swimming.

One night, while sitting at an empty intersection waiting for the light to change, I found myself coming up with reasons not to go through it. A car could smash into me. I could get pulled over. An unflattering photo of me taken from a traffic camera could appear in my mail.

But it wasn’t until I convinced myself the vengeful ghost of a woman — a woman wrongfully killed at that very intersection by another red light runner — would follow me home that I knew I had something special.

I’m confident anyone who reads my script will never go through a traffic light the same way again.

But don’t just take my word for it. Professional script consultant Danny Manus gave it a strong consider and called it, “A fast and enjoyable read with a solid climax, a couple good twists in the plot, some strong scare moments, suspenseful scenes, and enough gore to satisfy PG-13 horror fans while still having a solid mystery.”

So how isn’t this a movie yet? How am I still without a manager or agent? How did I keep you reading this long without the exchange of payment or sexual favors? Maybe you can educate an educator. I’m hoping you’ll give my script the chance for some extra attention and critique, but more importantly, I just want everybody reading it to have fun. Because I had a blast writing it.

Title: Ripper Squad

Genre: Action/Adventure

Logline: In 1888, an ex-cop seeking to unravel the mystery of his daughter’s death is recruited into an organisation dedicated to protecting London from fantastical evils. As our hero hunts for answers, Jack the Ripper commences his reign of terror with an apocalyptic plan that transcends mere murder. Men in Black meets the Victorian macabre as the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

Why you should read:

1. Am I a 20-something, college educated male?

Yes. Please don’t hold it against me.

2. In what ways are you fit to write for the screen?

I am a 20-something, college educated male. What else am I gonna do?

3. So your movie is PERIOD, BIG BUDGET and requires extensive WORLD-BUILDING? Sounds like a viable first script.

Yeah, right?

4. Why should I read it?

Because I think it’s a lot of fun. It’s puts a spin on a legendary figure from history (Jack the Ripper), funneling it through a commercial sensibility with strong action, and lively characters. I’ve always been fascinated by Victorian England, and felt that with its unique history of crime, tabloid journalism and mystique, the opportunity to write a Men in Black style adventure was super exciting. Hopefully the pitch whets your appetite, and even if it doesn’t, maybe you’ll give it a chance. I think it’s an enjoyable read.

Title: The Space Hotel

Genre: Sci-fi / Action

Logline: When a massive fire breaks out on the world’s first space hotel, a mismatched group of survivors must fight their way through twelve floors of chaos to safety.

Why you should read: After failing to win the Amateur Offerings weekend back at the start of the year I ripped everything out and started all over again with a page one rewrite, leaving only the unique setting intact (and even that has been developed and improved). Four months on, I have this new draft, with a tighter plot, more focused characters and plenty of new, not-seen-before, set pieces. Hopefully you’ll enjoy reading this version as much as I enjoyed writing it. Thank you in advance for any comments.

Title: The Siren Song

Genre: Thriller/Horror

Logline: A young doctor in a sea-side town becomes fascinated with a patient who plays a mermaid in the local carnival. After a series of strange occurrences, she reveals that she believes she may actually be a real mermaid that kills during the cycle of the full moon.

Why you should read: “The Siren Song” is a two year labor of love, that I think is ready to be put out into the world. Also, it’s a lean, mean 85 page reading machine.

Guys. I swear to you I’m not on Western and 3rd right now playing Pokemon Go. I swear I didn’t just catch Merfuffle and jump up and down while an old woman stared at me like I was crazy. But unfortunately, regardless of the fact that I am NOT playing Pokemon Go right now, I bring you the bad news that there is no post today. Or is that bad news? Might that mean you have more time to work on your REWRITES that you’re supposed to be doing??! Hmmmmmm???? I mean it is National Screenwriting Day today, a day I just made up the second I opened this document.

But I can’t leave you guys hanging. So I thought I’d offer a dialogue tip before I go. I’ve been noticing this mistake a lot lately so what better time to bring attention to it. Today’s tip is about LEADING QUESTIONS in dialogue. Guys, leading questions are baaaaaaad. A “leading question” is a question that artificially keeps the dialogue going. Usually, it’s a butchered way to extract information from a character for the benefit of the reader. Here’s an example from a post-apocalyptic script I just made up a second ago. In it, bad guys are descending upon the good guys’ base. Joe and Jane are part of the good guys:

JOE: We only have a few minutes before they get here.

JANE: And what happens when they get here?

Do you see that there’s no realism to Jane’s question. It’s only there to extract information from Joe for the audience’s benefit. So Joe would answer something like, “They’ll use our radio to contact reinforcements and then we’re toast. We have to protect that radio.” Is important information being conveyed? Sure. But it’s hackneyed and artificial. To avoid this mistake, try to see the dialogue as if it were happening in the real world, where your characters don’t have to inform a giant invisible audience of any information. If that were the case, I’m sure Jane would already know what happens when they get here. So the exchange would go more like this:

JOE: We only have a few minutes before they get here.

JANE: I’ll go warn Kate.

Much more natural, right? Of course, this begs the question, how do you then convey information that needs to be conveyed? Well, now we’re getting into a different discussion – hiding exposition. But the bare-bones answer is to get creative and avoid the obvious. One method is to make the audience do some of the work. That way they feel like they’ve earned the information. For example, the new exchange might go down like so:

JOE: Where’s the radio?

JANE: Kate has it.

JOE: We only have a few minutes before they get here.

JANE: I trust her.

Joe takes a deep breath. He’s not so sure.

While it’s not handed to us on a platter, we can deduce from this exchange that the radio is important and that it may need to be protected from these people who get here. The main point is you don’t want to get into a basic A-B “leading question,” “return answer” pattern in your dialogue exchanges. You want to avoid this:

MIKE: I need to go to the bathroom.

CAROL: Why do you need to go to the bathroom?

MIKE: That’s where I stashed the dope.

CAROL: What are you going to do with it when you get it?

MIKE: I’m going to call Frank.

CAROL: Why Frank?

Real world dialogue doesn’t work like that. So neither should movie dialogue.

If you’re new to the Scriptshadow Script Challenge, here are all the previous posts…

WEEK 0

WEEK 1

WEEK 2

WEEK 3

WEEK 4

WEEK 5

WEEK 6

WEEK 7

WEEK 8

WEEK 9

WEEK 10

Week 11!

Week 2 of the rewrite!

Happy times.

Assuming you haven’t ditched your script in favor of catching Pokemon, you’re knee-deep in a rewrite that’s probably causing you a lot of consternation. One of the shittiest things about rewriting is that, a lot of the time, the solutions you came up with in your outline won’t work. And because of this, instead of rewriting, you’re back to problem-solving. And when you’re problem solving, you’re not writing. Which means your script isn’t progressing.

What a lot of writers will do is let these difficulties linger. A day goes by, then two, then a week, then a couple of weeks. All of a sudden, you’re in the middle of full-blown writer’s block. The script becomes the enemy, and the only way to defeat it is to avoid it.

I read an article once by a professional screenwriter who said that with every script, you’ll have 3 to 4 moments where you encounter an INSURMOUNTABLE problem. You become convinced that your script is flawed and that it cannot survive. So before you freak out, know that this is something LOTS OF WRITERS endure.

Here’s the great thing about these moments. Solving them almost always raises your script to the next level. Something about solving this problem helps you see the script in a whole new way, and all of a sudden you’re reinvigorated, because you know your script is THAT much better. So don’t go jumping off a cliff when these moments arrive. Engage in the challenge, knowing that on the other side is a pot of gold.

What I DON’T want you to do is take time off. Or fiddle around on the internet. We don’t have time for that. We’re on a deadline. And remember, part of this experiment is preparing you guys for when you have real deadlines in the professional world. You need to be fighters. So here are five things you can do to overcome your script problems.

Book It – Read a book in a similar genre – Reading other peoples’ work, especially really good work, inspires people. And that inspiration can lead to ideas. And it’s only a matter of time before one of those ideas leads to a solution. There are a couple of things to keep in mind here. Do not read a book that’s in the exact same genre as your movie. The reason for this is that the solution you find may be the exact same solution they used, and now your script comes off as a copycat. Read something slightly different. So if you’re writing Star Wars, read something like Cloud Atlas.

Now if you’re really struggling to find the solution this way, here’s a trick. With every single unique element that pops up in the book, stop and ask yourself, “Could this work as my solution?” Let’s say, for example, that your problem is you want a unique murder scene in your movie, something unlike any murder scene ever made. You’re reading your book and you come across the sentence, “Joe moves the shower curtain to the side.” Think to yourself, “Shower curtain. Is there anything I can do with shower curtains? Hmmm. Maybe the murder takes place in a shower. Maybe we put the murderer, who’s really a man, in woman’s clothes to add to the confusion.” And just like that, you’ve created the shower scene from Psycho! That’s a bit of a stretch but the point is, YOU NEVER KNOW where solutions will come from. So consider every angle, even something as mundane as a shower curtain.

List it – One of the problems a lot of writers have is they think too logically. And to a certain extent, that’s a required mindset for screenwriting. Your movie has to make sense and characters have to act in a logical manner. But to come up with solutions, you may have to think illogically to spark the unconscious side of your brain, the side that’s truly creative. Lists are a great way to do that. What you do is open a new document and write down TEN or TWENTY solutions to your problem. The catch? You can’t judge your answers. The second you start judging, your logical mind takes over. We don’t want him around.

Now the reality is, a lot of your solutions will be cliche, because cliches are always the first things that come to mind. That’s why I prefer 20 solutions to 10. Once you get past 10, you’ll find yourself being more creative. Again, don’t filter yourself. Anything goes. Solutions often come from the most unexpected places. If we’re the writers of Zootopia, the best movie ever, and our problem is that we have no idea where our climax should take place, here’s what our solution-list might look like…

1) The forest.

2) Inside of an apartment.

3) The zoo.

4) Out on the farm where she grew up.

5) In the human world.

6) Underground.

7) In a supermarket.

8) We reveal that their amazing zoo world has actually been a simple zoo in the Bronx all this time. They just imagined it to be this way.

9) In a museum.

10) In a giant human office building where they have to steal something from the humans. Maybe the humans who own the zoo?

Are these great ideas? Uh, not really. But that’s okay! You’re not being judged on how great the idea is. You’re trying to spark your mind and think of the problem and its solution in a slightly different way. By not filtering yourself and writing down whatever the hell comes to mind, you just might find the answer you’re looking for.

Walk it – No, this doesn’t mean go for a walk and look for Pokemon. It means go out and THINK about your script. The reason walks work better than staying in your apartment is that you already know everything in your apartment. You know that TV over there, that chair over there, that plant over there. Your mind isn’t being challenged with any new information. Walk around and really TAKE IN your environment. Look at things you don’t normally look at. For example, look up. We stopped looking up when we were kids. Look fucking up! Look anywhere but the places you usually look. And during your walk, keep your problem front and center. Whatever you see, apply it to your problem. If you see a pink cadillac, ask yourself if a pink cadillac is part of the solution. If the driver has a handlebar mustache, ask yourself if disguising your main character in a handlebar mustache is the solution. Really let your mind wander and be creative. And try to take different routes each time out. Don’t always go on the same walk. Just like your apartment, the information will cease to be new.

Sleep it – This should be something you’re doing regardless of your rewrite. Every time you go to sleep, you should be thinking about the biggest problem in your script and trying to come up with a solution. This is the most peaceful time of the day, when your mind is at its clearest. Take advantage of that. But there’s a trick to this. Write the problem out in the form of a question AS SPECIFICALLY AS POSSIBLE ahead of time. One of the reasons writers struggle to solve a problem is they never clearly define the problem in the first place. The more specific the question, the easier it will be to solve. So let’s say we’re writing Ant-Man and the heist sequence isn’t working. You don’t want your question to be, “How do we make the heist sequence better?” Take a deeper look into WHY the scene isn’t working so your question can be more specific. Maybe it seems too mechanical, and you feel like it needs more emotion. Then the question can be, “How do we add more emotion to the heist scene so that the audience actually feels something?” And you can be even more specific than that. In fact, the more specific the question, the closer you are to the answer.

Write it – This may seem like the most obvious solution. Write your way out of the problem! But this is a complicated solution. If you don’t have a plan and you just start writing, you may write something so shitty that you never want to look at your script again. You may write something so shitty that you convince yourself the problem is unsolvable. You might dirty up the screenplay with some weird random glub of junk that, if complex enough, would require a lot of careful seeking and deleting to return your script back to the place it was before that horrible tangent. So here’s a compromise solution. Open a new document separate from your script and write the scene or sequence or changes in there. With it being an entirely new document, you don’t have to worry about it affecting your script if it sucks. You’re just experimenting, playing around, and seeing what works. This can be quite liberating as there’s literally NO PRESSURE. And I actually encourage writers to write several variations of the scene in the same document. Just see where your mind takes you. If you happen to come up with something that works? Simply cut and paste it into your official script!

These are just a few ways to help solve problems in your script so you don’t go into Writer’s Block World. Feel free to offer some of your own ways of solving script problems in the comments section.

Rewrite Goal (Week 11): End of first half of the script! (somewhere between pages 50-60, depending on overall script length).

Seeya next week!

Genre: Biopic

Premise: The true, and at times shocking, story of how the Oxford dictionary was created.

About: This was a big project around 2001. Mel Gibson’s company bought the rights to the book it was based on. At one point, Luc Besson was tapped to direct. The script’s original writer, Todd Komarnicki, has had a bit of a spotty career, but actually just landed a huge assignment. He scripted Sully, which you may remember me opining about in my newsletter. The script was then rewritten by writer-director John Boorman, who’s done a million things, including Excalibur, Exorcist 2, and a dialogue polish on Deliverance.

Writers: Todd Komarnicki (rewrite by John Boorman) (adapted from the book by Simon Winchester)

Details: 121 pages

How does one make the dictionary interesting?

How does one make any inherently boring subject matter interesting.

I’ll tell you how.

Murrrrrrrr-derrrrrrrrrrr.

Like Pokemon Go or Chewbacca Mom, murder makes everything more palatable! And that’s what caught my interest with this long forgotten project. You see, unfortunately for “Madman,” it hit the streets long before the biopic craze. Hell, even before the Black List craze. And therefore this offbeat tale of how the Oxford dictionary was conceived never built enough buzz to turn the light green.

If this had been written today, however? I have no doubt it would already be in production. True, Squirtel or Bellsrpout might have played a prominent part. But who ever said making movies was easy? Quentin Tarantino almost cast a no-name female actress as one of the gang members in Reservoir Dogs because her boyfriend promised to give the production 1 million dollars. Casting Squirtel as a dictionary is a no-brainer.

It’s 1872. It’s London. It’s dirty. But most importantly, it’s a definition-less city. All this language is being bandied about by 3 million people, yet nobody has a reference for how to correctly say any of it.

James Murray wants to change that. He wants to do what Oxford has tried and failed to do for decades now – write a dictionary. A container of every single word and its definition in the English language. The reason this hasn’t been accomplished yet is because nobody knows how to accomplish it! Nobody even has a game plan for rounding all these words up.

Enter Dr. Minor. Actually, let’s back up a little. Dr. Minor was a surgeon in an American war who branded a soldier with a giant “D” on his face after that man tried to desert the army. After the war was over, Dr. Minor became convinced that the soldier was attempting to find him and kill him.

Dr. Minor escaped to London, only to find the man still stalking him (or so he believed). He finally ran into D-Man and shot him dead. Except it turned out Dr. Minor didn’t shoot the correct man. It was just some random Londoner. After going through the English court system, Dr. Minor was considered crazy-town, and sent to an asylum.

From there, we cut back and forth between Murray’s tireless quest to find and define all the words ever, and Dr. Minor, who becomes sort of the “Andy Dufresne” of his asylum, helping others learn art and accumulating a mini-library in his cell.

When Dr. Minor hears that Murray is building a dictionary from scratch, he decides to help, meticulously going through every book he owns, writing down a definition for each word, and sending them to Murray.

In the meantime, Dr. Minor must deal with the guilt he feels over leaving a woman and her children without a husband and father. And when he tries to mend that fence, eventually meeting the widow for the first time, things don’t go as planned. I suppose that’s why life cannot be defined.

Have you ever thought of how difficult it would be to create a dictionary from scratch when one had never been written before? Think about that for a minute. You don’t have the internet, remember. You don’t even have a list of the words to define yet! Where would you begin?

That question definitely pulled me in. But then reality hit. How would you DRAMATIZE that? That’s the question you must ask with any idea you come up with. How do I dramatize this? In some cases, the idea itself incites drama. In other cases, you’ll have to go looking for it. It is my belief that if you have to go looking for it, it probably isn’t a movie-worthy premise.

Drama /drämə/ (noun) – an exciting, emotional, or unexpected series of events or set of circumstances.

To understand that statement better, here are two premises. Notice how one is dripping with dramatic possibility, while the other doesn’t have a dramatic bone in its body

1) When a private plane full of rich passengers crashes on a barren island, the people on board will devolve into the worst versions of themselves in order to survive.

2) A private plane escorting a soccer team to the West Coast allows its passengers to explore the power of friendship.

Do you see the difference here? How the first idea bleeds drama, meaning you can already imagine tons of scenes in your head. Whereas with the second one, you probably can’t think of a single scene. This is the kind of thing to be aware of when coming up with ideas. “Do dramatic scenes start popping up in your head after reading the premise?”

To “Madman’s” credit, it finds SOME dramatic elements. But it’s not as juicy as the title would have you believe. The big murder that takes place happens at the beginning of the movie, and then that’s it as far as murder.

Pokemon Go /ˈpōkiˌmän/ (noun) A video game by which people with little to no lives chase miniature monsters in a virtual world created by their phone.

I thought there was going to be some competition – like two dictionary groups trying to beat each other out to win the historic prize of first-ever-dictionary. And that they would’ve resorted to murder to win the competition.

The reason that would’ve worked better is that now you have something to BUILD TOWARDS. You can build towards the growing frustration, the growing tension, the impending murder. We know that things are coming to a head and we’re excited! But when you murder someone before the main story even begins, you’ve eliminated that chance to build.

We talked about this yesterday. We built towards this big rescue, but then were done with it by the midpoint. What’s left to build towards? That’s another question you want to be aware of. Am I still building towards the most powerful moment in the story? Because if the most powerful moment in your story is in the rearview mirror, there’s something wrong with your structure.

“Madman” does its best to mitigate these problems by creating a strange love story between Minor and the woman whose husband he killed. And then with Murray, we see him stressing out a lot under the pressure.

But where the story really struggled was in its stakes. The script never answered the question: WHY DID THIS NEED TO BE DONE? And WHY RIGHT NOW? If they failed, what would happen? Lots of bad grammar? Time has proven that we’re going to have that problem whether there’s a dictionary or not.

I’ll give you an example of stakes from another English period piece with a somewhat similar setup: The King’s Speech. The King attempts to get rid of his stutter in order to warn the world of Hitler (just like Murray is attempting to finish this dictionary) with the difference being that HIS SPEECH MATTERED. It needed to be done. And fixing his stutter did matter RIGHT NOW because time was running out to stop Hitler.

As far as I can tell, finishing this dictionary is more of a prestige thing. Everyone involved just thinks it would be rad to achieve it. That’s fine. But that’s not movie stakes.

Despite this, “Madman” moves along with just enough strangeness to keep you curious. Dr. Minor, for example, was convinced that the man chasing him could raise spirits from Hell to find him. And who would’ve thought he’d bag the woman whose husband he killed?? I mean I’ve seen some strange attempts to get a woman’s attention before, but never one quite like that.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If your script covers a long period of time, and therefore doesn’t have a lot of urgency, a nice trick is to add a cross-cutting storyline that will help move through time effortlessly. We saw this with The Martian. By cutting back to earth, we could come back to Matt Damon 3 months later and the audience wouldn’t blink. That same 3-month jump becomes a lot more prominent if we’re with Matty the whole time. We do that here too. One of the ways they disguise the years it takes to write this dictionary is by cutting back and forth between Minor and Murray. Each time we cut, we do so 3-6 months ahead. So if masking a huge swath of time is a problem, consider a second narrative you can jump back and forth from.

What I learned 2: Potentially mundane subject matter is the perfect subject matter to add weirdness to because it’s unexpected. For instance, if I said I’m writing a movie about the ice cream truck business, you’d be like, “Wonderful. Let me know how it goes.” But if I said I was writing about a war between two ice cream truck drivers fighting over the same turf (a real project that just got picked up), that combination of mundane and weird would intrigue you.