Today we look at an old Blade Runner 2 script and get an idea of what the sequel to the cult classic might look like.

Genre: Science-Fiction

Premise: When an old blade runner flies into Los Angeles to find someone who can save his dying soul mate, he’s targeted by a young breed of blade runner who’s tasked with taking him out.

About: If there is a project that more exemplifies “Development Hell” than Blade Runner 2, I’d like to know what it is. Over the past 25 years, the project was happening, then it wasn’t, then it was, then it wasn’t. Harrison Ford was involved, then he wasn’t. Ridley Scott was involved, then he wasn’t. Well the project has finally come together with one of the flashiest packages Hollywood can offer. You’ve got Harrison Ford reprising his role. You’ve got Ryan Gosling playing the young blade runner. And you’ve got Denis Villeneuve (Arrival) directing. It should be noted that this is a 1997 draft of the script so I have no idea if they’re using the same plot or not. A novel for Blade Runner 2 was written, which is what this draft is based on. The writer, Stuart Hazeldine, has been pretty absent in Hollywood since he wrote this draft, until recently when he just got a huge directing gig with The Shack.

Writer: Stuart Hazeldine (based on the novel BLADE RUNNER 2 by K.W. Jeter)

Details: 126 pages (November 1, 1997 draft)

Okay, real talk.

Blade Runner is a visual and aural masterpiece and one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made. There’s no disputing that. The iconic shot of a car flying towards the giant exterior television with the Vangelis soundtrack playing in the background? Magical.

HOWEVER.

From a screenwriting standpoint, the film leaves something to be desired. Narratively, it starts out strong, then wonks around through a casual second act, before sort of coming together at the end. The reason given for why Blade Runner was never popular with audiences was that it was too “edgy” or too “dark.”

B.S.

In reality, the screenplay wasn’t very good. A stronger story would’ve meant stronger word of mouth which would’ve meant more people seeing the film.

Look at Arrival (ironically directed by the same person who will be directing Blade Runner 2). Offbeat sci-fi film that’s been a box office bonanza built entirely on word-of-mouth.

I guess that’s what makes the movie unique though, and like an obscure band, it’s always more fun to prop up what others don’t like. Will Blade Runner 2 change the narrative, or keep the offbeat sensibilities of the first film?

It’s been a decade since we last saw Deckard, our former LAPD blade runner who’s now hiding in the countryside with Rachael, the replicant he fell in love with. Replicants are only supposed to be able to live four years. But Deckard has built a cryo-chamber that’s extended Rachael’s life.

Unfortunately, even with life extension, Rachael’s going to die soon. That is, unless, Deckard can find someone who knows how to hack the “life limitation” code inside replicants. So he heads back into dangerous Los Angeles to visit an old friend who may be able to point him in the right direction.

Meanwhile, Deckard’s old boss learns that he’s back in town. Since aiding a replicant is illegal, he tasks a snazzy new blade runner, Andersson, to find and kill Deckard. In case you were wondering, the extra ’s’ in Andersson stands for “slick.”

Deckard’s journey leads him back to the Tyrell corporation, the place that makes the replicants, where a new woman named Sarah is now running the company. Sarah tells Deckard she wants him to finish the job he started a decade ago – find and kill the sixth replicant. If he does that, she’ll give him the key to extending Rachael’s lifespan.

And so the race is on. Deckard has no idea who this replicant is or what he looks like. But he must find and kill him before a determined Andersson finds and kills him first.

Blade Runner 2 has a traditional story setup. Deckard’s “wife” is dying. So he agrees to “one last job” in order to save her. What’s unique about Blade Runner, though, is the replicant twist. The person our hero is trying to take down could be anyone. Hell, he could be the guy staring back at you in the mirror.

Also, as with every good story, you want to add urgency if possible. Deckard running off and trying to find a replicant unimpeded is fine. But not as exciting as if Deckard is being chased by a cop who’s trying to kill him as well. Every moment is heightened when there’s someone on your heels.

A lot has been made of Blade Runner’s unapologetic darkness. As we all know, the word “dark” gets geeks more revved up than an IMAX preview of a new Christopher Nolan film. It is the operative word for cinephiles getting hot and giggly. It doesn’t matter if a sci-fi film is TERRIBLE. If it’s dark, there will be geeks who stand by it til the end.

One of the distinguishing characteristic between a dark and a “light” movie is the goal of the protagonist. If the protagonist is attempting to KILL someone, the overall tone of the movie will be dark. If the protagonist is trying to SAVE someone, the overall tone will be light.

What’s the goal of the original Blade Runner? – Go and kill some dudes. What’s the goal of this new one? – Go kill the final replicant. We even have a SECOND blade runner being tasked with trying to kill our hero.

Hollywood knows that darkness equals less box office, so they’re always fighting back against these narratives to give them some light. For example, Deckard is doing all of this to SAVE SOMEONE’S LIFE. This offsets the darkness a little, improving the chances that more butts show up in seats.

I think that’s why one of the darker movies in history, Silence of the Lambs, also made a ton of money. Yes, Clarice was tasked with (essentially) killing a man. But she’s also trying to save someone as well. They found the perfect balance in that story.

In comparison, did any of you see that 2010 movie, Edge of Darkness, starring Mel Gibson? You probably barely remember it if you did. That’s because the movie is about a dude who wants to kill the people responsible for killing his daughter. It’s dark and sad because it’s solely about killing. There is no light.

And therein lies the quandary. You get “street cred” as a writer for going dark. But you get money and jobs for going light. It’s why writers are obsessed with straddling that line to find the perfect balance – writing the next Silence of the Lambs.

Getting back to Blade Runner 2, this script, from a storytelling perspective, is actually stronger than the first film. It has more going on. But that doesn’t mean the film itself will be better. Blade Runner is one of the top 5 directed sci-fi films of all time, maybe top 20 directed films of all time period. From a DIRECTING perspective, it’s amazing.

So if Denis is able to capture that same magic, and he rides this more active plot (assuming they’re doing something similar) he may achieve what Scott could not – a dark movie that also breaks through to the popular masses.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re struggling with a tone that’s too dark, add more saving!

Note, to read Monday’s script review, scroll down or go here.

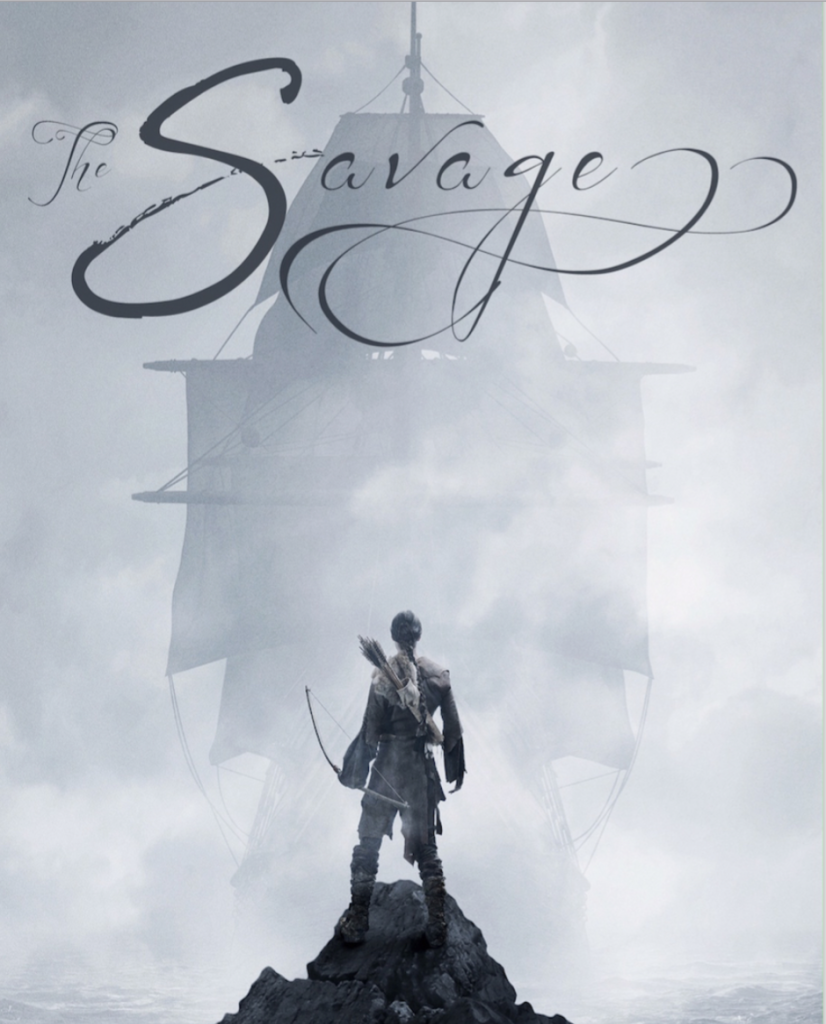

THE SAVAGE!!! BY CHRIS RYAN YEAZEL!!!

Genre: Historical Biography

Logline: The incredible true story behind one of America’s founding myths. After being kidnapped from his lands as a child, the Patuxet Indian Squanto spends his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that changes the course of history.

You can download and read the script yourself here:

For those coming across this tournament for the first time, I wanted to try something different. Instead of doing the traditional screenplay competition thing where you send a script out, wait four months, and desperately hope to get that e-mail that says you’ve advanced, I wondered what it would be like to play the competition out publicly. Not only that, but to have real people vote on the scripts. Not a couple of overworked screenplay competition readers.

A little over 500 scripts were submitted. I then chose 40 of those to partake in the competition. And via tournament-style elimination, the scripts fought against each other one round at a time. The Savage, which went in as the top ranked script, came out as the top ranked script. That’s better than Andy Murray can say at the Australian Open.

I want to take a moment to congratulate the runner-up, Billie Bates, and her script, The Bait. Billie had a strong showing all the way up the final, winning all her rounds soundly. And I want to thank and congratulate everybody who participated. This was such a unique experiment. I know it got bumpy at times. But overall, I had fun with it. I’m actually curious about what kind of changes you would make if we did the competition again. Please share your thoughts in the comments.

I will be reviewing The Savage this Friday. One of the hardest things about this contest was not getting too caught up in the script discussion. I knew I’d be reviewing one or more of these scripts eventually, so I didn’t want to know too much going into the reviews. FINALLY I get to see what all the hype is about.

Once again, congrats Chris. Amazing job. And, oh yeah, start getting those short scripts ready people!

We have a Scriptshadow first. A What I Learned section where the lesson we learn is explained not by me, but by the writer himself within the script!

Genre: Drama/Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) Tasked with finding a game changing take for the sixth Jason Bourne movie, Tom Milton goes deep down the rabbit hole of cracking the story. With the guidance (and abuse) of a professor from his past and Bourne himself, Tom begins workshopping scenes that begin to bleed into real life in unexpected ways.

About: Mattson Tomlin is a writer/director born in Romania who’s been active on the short film circuit. But this Black List entry (at 8 votes) is the first thing that’s put him on Hollywood’s map.

Writer: Mattson Tomlin

Details: 103 pages

Before we get to today’s script, can we take a moment to acknowledge that M. Night’s latest film just made 40 million dollars on its opening weekend? What year is this, 1999? I thought “Split” would make half that if it was lucky.

The new narrative on Night is that he’s financing his films himself so there’s no studio interference, the idea being that all those Night misfires you had to sit through weren’t Night’s fault. They were the studio’s fault!!!

Hmm, I’m not sure I buy that. There isn’t a filmmaker on the planet who had more freedom than Night after Signs (which, despite being an average movie, made huge box office). He had three movies there where they let him do anything he wanted.

Anyway, did anyone see Split? Was it any good?

Moving on, I chose today’s script for one simple reason. I secretly think all Bourne movies are exactly the same. Not in the way that all Star Wars movies take place in space or all Bond movies have Bond traveling the world. I mean like, they all have the same plot, they all have the same cinematography, they all follow the same narrative. I’m not sure there’s a franchise that’s squeezed more mileage out of its one-trick pony than this one.

So the idea of a writer trying to crack the next Bourne film is funny to me. I mean, seriously, how do you make one of these movies different?

29 year-old Tom Milton finds himself in one of those ‘battle-it-out’ writing assignments. Him and another writer have been separately assigned to write drafts of Bourne 6, and the writer who writes the best script gets the job.

But Tom is struggling. Everything he writes comes off as (surprise surprise) the same boring action stuff Bourne always gets caught in. Specifically, Tom’s stuck on a scene where Bourne walks into a building and is attacked by two henchman, just as the cleaning lady walks into the room.

The scene is so difficult to write that Tom goes to his grumpy old professor, Ron Sparrow, at AFI and asks him for advice. Sparrow, who’s as no-bullshit as they come, notes that Tom’s not finding the truth of his characters. He wants Tom to dig deeper, to figure out the lives of every single character in his screenplay.

As Tom descends into the madness that is writing a screenplay that isn’t working, he begins placing himself in the scenes along with Sparrow. The two then interact with the characters, even Bourne himself, to figure out how to solve the script. But will the executives dig a Bourne script with actual character depth? Or will they go back to the tried and true formula that’s made them billions worldwide?

I feel like every writer, at some point in their career, writes at least one of these scripts, where you’re deconstructing screenwriting, a la Charlie Kaufman, to the point where the writer himself is including himself in the story.

But there’s a precedent here. Kaufman used to write these scripts in his sleep. And Sam Esmail, before Mr. Robot fame, used to love writing these kinds of screenplays. And, of course, Woody Allen used to do this. So you can’t just roll up and say, “Look at how creative I am.” Just like any genre, you have to find a fresh take on the formula.

To “A Deconstruction’s” credit, it didn’t go where I thought it would go. And there are a few moments in the middle of the script where it shined. But this never felt like anything more than an experiment. Whenever I feel choices are being made right there on the page (the writer is figuring out a plot point as he’s writing), I lose confidence in the story.

For example, late in the script, (spoiler) Tom looks directly into the camera and we back up and see all of the crew shooting this movie in which Tom is the star. That seems like something you write when you’re out of ideas. It wasn’t in alignment with the rest of the script, which was a simple but fun movie about deconstructing an action franchise to find the truth in the characters.

With that said, “Deconstruction” had this really nice sequence that all screenwriters should read. In Tom’s first draft, he keeps getting stuck on a boring scene where a Henchman tries to shoot Bourne before Bourne dismantles him. He asks Sparrow, “Why is this scene so boring?” And Sparrow says, “It’s because you’ve named this guy ‘Henchman.’ You need to find out who this guy is. Once you do that, the scene will come alive.”

So Tom goes back through the henchman’s life, learns he had a really tough upbringing, followed in his mentor’s criminal footsteps because it was the only option he had, and before his mentor died, he gave Henchman his switchblade. And the henchman cherished that switchblade. It was the entirety of his memory of the only man who ever cared about him. In many ways, he was his father.

So now we go back to the Bourne scene again. But this time, instead of pulling out a gun, our henchman pulls out that switchblade. And instead of going down easy, he fights with the zeal of a thousand henchman. And he brandishes this switchblade like he was born holding it. Because that switchblade is his life.

It’s not just a fun moment. It’s a valuable lesson on how to improve characters and scenes. A character comes alive once you actually know something about him. If you know nothing, they will offer nothing.

Unfortunately, I don’t think the rest of the script is there yet. There are a dozen little messy things about it that keep it from reaching its potential. For example, I didn’t understand what kind of professor Sparrow was. I think he was an acting teacher. So it didn’t make 100% sense why he was helping Tom with screenwriting. There were a lot of little incongruent things like that that threw me.

With that said, the script is different. It’s not a biopic or a true story. So if you’re tired of suffering through those, Deconstruction is a nice change of pace. It wasn’t for me in this iteration. But maybe future drafts will help it reach its potential.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Every character has a history. Even characters without names. I’m not going to tell you to write backstories for every single character in your script, even the waiter. But I can promise you this – THE MORE YOU KNOW ABOUT A CHARACTER, THE MORE THEY’LL BRING TO THE SCENES THEY’RE IN. If you look at the henchman example, the scene DEFINITELY became better once the henchman attacked with that switchblade as opposed to a gun. So if you’re stuck in a scene, the answer may be to get to know the characters within that scene better by separately diving into their backstories. Their past may hold the key to unlocking the scene.

Come one, come all, to the finals of the Scriptshadow Tournament! The day has finally arrived. After 500 entries, a first round of 40 chosen participants, a quarterfinal round, a semifinal round, and a whole lot of controversy, the checkered flag is just 48 hours away!

The Scriptshadow Screenplay Tournament is the only tournament that tells competition know-it-alls and Hollywood “gate-keepers” to screw it. That’s because you – yes YOU! – the readers, choose who wins the competition.

Here’s how voting works. Read as much from each script as you can then vote in the comments which script you think deserves to win. Please explain why you voted for the script. This is the finals and we want to make sure everyone is voting for something they loved.

Today’s face-off isn’t unexpected. These two scripts were ranked number 1 and number 3 going into the tournament. They were expected to do well. The Bait has basically cruised into the finals, winning all of its rounds easily, whereas The Savage had an incredibly close Quarterfinal round, barely squeaking by Divide and Connor, before rebounding with a strong semifinal win.

These scripts are so different, I have no idea how the final will play out.

If you are a frequent or just a casual Scriptshadow reader and you have time this weekend, please read these scripts and vote. Your vote could determine the winner.

Voting closes at 10pm Pacific time Sunday night and the winner will be announced in a separate post Monday morning.

And with that… GOOD LUCK YOU TWO!

#1 SEED

Title: The Savage (new draft)

Genre: Historical Biography

Logline: The incredible true story behind one of America’s founding myths. After being kidnapped from his lands as a child, the Patuxet Indian Squanto spends his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that changes the course of history.

Writer: Chris Ryan Yeazel

VS.

#3 SEED

Title: The Bait (new draft)

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Logline: An untrusting woman, employed to test men prior to marriage for concerned wives-to-be, has her world upended when she falls for her latest target while he remains rocksteady in denial of their mutual attraction, and she must reconsider her beliefs on love, trust, and what it means to tempt fate.

Writer: Billie Bates

You may not have heard yet, but the next contest here at Scriptshadow is a SHORT SCRIPT CONTEST. And the winner is going to get his short PRODUCED. We’re going to shoot it, edit it, then premiere it here on Scriptshadow. How exciting will that be!

We’ll get into the details of the contest in the coming weeks. But right now, I want you guys to start writing shorts. That’s right, shorts with an “S.” One of the shitty things about a feature script is it’s a huge commitment. That’s why you have to prep so much (getting feedback on concepts, outlining, etc.). Cause once you get on the train, you’re not getting off for months.

The great thing about short scripts is you can bang them out quickly. Hell, you could write a short in five minutes. TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THIS. I would encourage all of you to write AT LEAST 10 short scripts before choosing which one to send me. Write five of them today. Or make a deal with yourself to write one a day for the next ten days. Identify the one that pops the most, then rewrite it into a masterpiece.

How do you write a short masterpiece? Here are some guidelines to get the most out of your short script…

CONCEPT

This doesn’t change from features. If you don’t have a good concept, nothing you write will matter. A good concept feels bigger than real life. The opening to the movie, Scream, is basically a short movie. A young woman home alone. A man calls her. Wants to play a game where life and death are at stake. If you’re going with something more “real life” driven, try to find some irony. An ice cream truck owner who gets in a nasty war with the adjacent ice cream truck. But these are specific examples. A good concept is anything that excites someone when they hear it. Imagine yourself pitching your idea to someone. Do they say, “Whoa!” or do they politely reply, “Sure, that sounds cool?” If you can’t come up with anything, start with a dead body. Lots of great movies start with a dead body.

BUDGET

Because short movies don’t make money, budget is always a concern. Therefore, your locations will need to be limited. However, instead of letting that deter you, let it excite you. You can use contained locations to your advantage, as they provide an opportunity to trap or limit your characters, both things that lead to more dramatic storytelling. You should never limit your imagination. But keep in mind that funds are scarce for this format. Best, then, for your story solutions to be simple rather than elaborate.

GENRE PIECE

The reason that a large majority of short films garner less than 200 views on Youtube is because they don’t embrace genre. Bread-and-butter shorts about friendship or philosophizing or life or two people in a coffee shop talking – it’s not that those shorts can’t be good. But nobody watches those shorts and says, “Oh man, I HAVE to send this to my friend!!!!” Science-fiction, horror, time-travel, fantasy, action – these are way more likely to excite viewers and get them to pump up your view-counts. If you have a choice between a non-genre piece and a genre piece, I advise you to go with a genre piece.

JUMP IN RIGHT AWAY

One of the most common things I see in successful shorts is that the story starts out immediately. The reason for this is that all shorts are watched on the internet, where the viewer’s hand is on a device that, the millisecond it’s bored, has the ability to jump to another website. So if you bore someone within the first 20 seconds of a video, they’re gone. For this reason, you want to try and capture the viewer’s interest right away. This does not mean with action. It could be with mystery or just a weird mysterious shot. At the very least, make sure something is happening. Because if you’re not thinking about capturing the viewer right away, you’re limiting the appeal of your short.

SHOCK VALUE

Some may see shock value as cheap. But when you’re telling a 4 minute movie, you have to use every tool at your disposal, and shock value shorts get passed around all the time. Shock value could be a character screaming racist things right at the camera (early Spike Lee). Or could be something with intense violence. Or my friend wrote a short about a guy who was cursed with seeing everyone naked (until meeting the girl of his dreams, the only person he could see clothed). A short with all naked people? That would get passed around. Shock value is not necessary to write a good short. But a good shock value concept can get a killer amount of views.

SUSPENSE

Suspense is one of your best friends in short film writing. One of the simplest and effective setups is to introduce us to a character, imply that something bad is going to happen to them, then suspend the outcome of that bad thing until the end of the story. Watch Psycho for research, which is really a series of short suspenseful films. Notice how a scene where a criminal is buying a car, with a suspicious cop nearby, can turn into a hell of an entertaining scene. Any Hitchcock research should give you lots of short ideas.

EMOTION

Emotion is the one area where most short films fail to shine. And that’s because most shorts are director-driven and directors don’t know how to mine emotion as well as writers. So this is the area where you can bring your expertise to the table. Emotion mainly boils down to creating characters we care about and placing them in peril (whether it be emotional or physical). A man negotiating the release of his kidnapped son can be heartbreaking if written well.

GET CLEVER

Short films are one of the best places to experiment. Wacky narratives that get tiresome over 100 minutes could be perfect for 5. Don’t limit yourself to linear storytelling. Jump around in time, in space. You could tell your story backwards. You could do a Sliding Doors type thing where you’re showing two different timelines of the same person. You could do time travel. You could do an unreliable narrator thing where what we’re being told isn’t what’s happening. Shorts are one of the best places for super-creative people. This is your opportunity to show just how clever (or weird) you are. Just make sure it makes sense in the end.

A GREAT FUCKING ENDING

Shorts are these bite-sized stories that we watch quickly and move on from. In order for us to want to share them with others, they really have to resonate. One of the easiest ways to do this is a big ending, a twist or a shock that hits the viewer right between the eyes. And because your story is so small to begin with, it almost feels pointless without a punch of a finale. For this reason, try to think of your ending in conjunction with your concept. Go out with a bang if possible.

A FEW FINAL THOUGHTS

Pictures can be helpful in coming up with short ideas. Go to one of those random image sites (can anyone list a good one in the comments?) and watch your imagination spark to life. — Don’t write a short with people in an apartment while the end of the world is happening outside. That short idea has been done to death. Unless you have a fresh take on it of course. — Also avoid “multiplicity” type shorts, where one person keeps getting cloned. I’ve seen that idea far too often. And it’s never good. — Finally, a great idea trumps everything. If you have a stupendous short idea that doesn’t follow a single rule I listed above, WRITE IT. The above are merely guidelines for what tends to work best in short film writing. I wouldn’t be surprised if the winning short is so unique that it ignores many of the thing that I’ve talked about.

INSPIRING SHORT FILMS

Stutter – emotion, concept

Controller – genre, emotion

Fortune Cookie – clever, ending

Cargo – genre, emotion, ending

Dead Island – emotion, clever

Noah – Clever, emotion

The Black Hole – clever, ending

PLEASE SHARE LINKS TO YOUR OWN FAVORITE SHORT FILMS IN THE COMMENTS! LET’S INSPIRE EACH OTHER!