Genre: Drama

Premise: Spanning thousands of years, we follow three separate storylines that deal with the universal questions of love, death, and time.

About: This script finished in the top 10 of last year’s Black List. The writer, Colby Day, is a brand new writer on the scene. He wrote one extremely low budget movie in 2011, but for all intents and purposes, this is his breakthrough moment.

Writer: Colby Day

Details: 97 pages

One cannot think of the “spanning time sci-fi” genre without mentioning Cloud Atlas. That film is arguably the most beautiful science fiction film ever made. Which shows you just how bad it must have been that nobody ever speaks of it.

The problem with spanning time movies is that the writer seems more excited by the fact that he can cut between 12,000 B.C. and 2400 A.D, than actually creating a compelling story! Seriously. Everyone wants to copy that bone thrown up in the air, cut to space 2001 shot because – let’s face it – IT’S FUCKING COOL!

But cool cuts between vast gaps in time make up maybe 1/10000 of your screenplay. You still have to tell an entertaining story. Did today’s script do so? Let’s find out.

We start out in 45,000 B.C. That’s where we meet our Neanderthal family of Thorn, his wife Hera, and their daughter, Lark. For this tight-knit group, the goal is simple: SURVIVE. It isn’t just the harsh conditions they live in that threaten them. It’s that they have no knowledge of medicine, no knowledge of anything. If someone gets sick, it’s very likely they’ll die.

Cut to present day where we meet Claire, a professor who studies history, specifically the Neanderthal people. Claire’s a bit of a bitch, and when she’s not carbon-testing bones, she’s fending off resident geek and fellow professor, Greg. Claire detests Greg but since he’s the only guy giving her any attention, she keeps him around.

Cut to 2217, where we meet Coakley, a young woman genetically altered to live for hundreds of years. Coakley is on a spaceship headed to a planet in another solar system which she plans to populate with a bunch of frozen babies she’s hauling downstairs. Her only company is Rosco, the female A.I. on the ship responsible for keeping Coakley alive. When the ship’s hydrogen generator goes down, Coakley has to figure out a way to fix it, or die.

The script cuts back and forth between these three storylines, and then, as we move into the final stages of the story, we push further and further forward in time, until we’re spanning entire generations. It is the most noble attempt at covering the plight of mankind in under 100 pages that I’ve ever seen.

Let’s get back to that question. Is In the Blink of an Eye a good story or is it time masturbation? The only way we can answer that question is to look into the individual storylines and see what kind of story engines are driving them.

We’ll start with the Neanderthals. Now as I’ve mentioned many times in the past, the two most powerful story engines are a specific goal or a mystery. Those two engines drive 95% of the best movies out there.

There’s a goal in the Neanderthal section in “Blink” but it’s a general one: To survive. General goals can work, but the characters have to pick up the slack that the plot’s not offering. And of the three storylines, the Neanderthals are the most sympathetic. We see them lose two babies and a mother. We see them battle disease and the elements. So I was invested in them.

The problem is the problem that always happens when you have a non-specific goal. The ending is weak. If you’re not pushing towards something specific, it’s hard to know where to end your story. And here, we just watch Neanderthals give birth to more Neanderthals who give birth to more Neanderthals, and that’s sort of it. I wasn’t sure what to make of that.

Let’s talk about the present day then. Claire doesn’t have a specific goal. Nor is there a mystery in place. However, as we’ve established, if you don’t have a story engine, you can still save your story with a great character. The problem is, Claire is a total bitch. She’s rude to this really nice guy who really likes her and only wants to do good things for her. So this was a tough storyline to get invested in. I kept wanting them to connect Claire’s research to the Neanderthal storyline in a concrete way, but it was all very vague.

Of the three storylines, Coakley’s is the only one with a concrete goal: To colonize a new planet. The benefit of having a goal in your story is that you can place obstacles in front of that goal, and because you have obstacles, you now have drama.

With Coakley, we get this entire sequence where she needs to figure out why the ship isn’t producing hydrogen or she’ll die. Because of that, she has to make one of the most difficult decisions in the script – she has to reboot Rosco. Rosco points out, “But doesn’t that mean you’ll be killing me?” The Rosco that comes back will not be the same Rosco she’s been with this whole time. It’s a torturous decision.

Compelling dramatic moments like this can be traced back to the power of the goal. Without the goal, we couldn’t create the obstacle. And without the obstacle, we couldn’t create a solution that only included the difficult decision of killing your only friend.

It seems to me that Colby Day was less interested in writing a well-conceived plot, and more into tackling the thematic nuances of time and death and the universe. And I totally respect that. I mean, that’s basically what 2001 did.

But whenever somebody does this, I can’t help but wonder whether they did it because it’s easier. It’s a million times easier not to connect things. It’s so much harder to dig in, do the hard work, and figure out how to directly connect storylines from 200 years apart, from 45,000 years apart. So a lot of writers will just say, fuck it. I’ll go the thematic route and position my script as a thinking-man’s piece that leaves its answers up to the viewer.

Takes me much less time. If it works, I look like a genius. Win-win.

With that said, I’ve been saying I want more original screenplays and this is definitely that. Thumbs up to Day for not giving us another biopic. If I had to read one more logline that started with, “The true story of an underdog stock trader in the midst of a midlife crisis who was the first man in World War 2 to meet the Beatles while Stephen King wrote his first book…” I was going to blow my brains out.

In the Blink of an Eye was just too “floaty” for me. I wanted something concrete. Something I could put my hands on. It’s not a bad script. It just wasn’t my thing.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re jumping back and forth between timelines, strong narratives within each of those timelines help. Without concrete story engines that push your characters forward with gusto, we’re always getting dropped back into a laid-back atmosphere, one that takes us awhile to remember what’s going on and why it’s important. There’s no wrong way to write a multi-timeline screenplay, but my experience reading these scripts has taught me that without strong engines powering the individual stories, you’re making things very hard on yourself.

Genre: Period/Spy

Premise: In 1976, during a critical point in the Cold War, a Russian female spy is assigned to get close to an American spy who may have information on one of Russia’s biggest moles.

About: Red Sparrow is a best selling novel that won the Edgar Award for best first novel, given to author Jason Matthews. The book has since been adapted by Eric Warren Singer, who scripted the very good American Hustle. I’m a little confused over what I’m reading today, since the book deals with a modern day spy story, and the script sets us back in the heart of the Cold War. Either way, they’re planning on this being a franchise, with at least 3 films. It will star Jennifer Lawrence and Joel Edgerton.

Writer: Eric Warren Singer (based on the novel by Jason Matthews)

Details: 132 pages – undated

I’m curious what they’re going to do here. Because one of my first criticisms after reading the script was, “You’re really going to set a major Hollywood picture in Russia in 1976?” Like, are you purposefully trying to make it so no one shows up?

Then I heard the novel was set in the present day, which at least made more sense from a marketing standpoint. Here’s the problem with that, though. Today’s relations between the U.S. and Russia do not have the same dramatic effect as the “at any moment the world could blow up” period of the Cold War. So there are pros and cons to going either way. Maybe they’ve since come back to the modern-day storyline after this Trump-Putin stuff. I don’t know.

So we shouldn’t take this script to be representative of the final product. Still, there’s a lot to learn from it, most notably how a writer should know when and when not to cut plot. So let’s dive in.

It’s 1976 and Dominique “Dom” Egorov is a honeytrap, a Russian spy who specializes in making marks fall in love with her so she can steal their information and pass it back to the motherland. We meet Dom as one of her lovers realizes she’s a spy and what that means for his career, and therefore slits his wrists right there in front of her. Dom, who’s spent every day of the last six weeks with this man, calmly walks out the door, not even the slightest hint of emotion on her face.

Cut to Nate Nash, a reckless CIA agent stationed in Russia, whose key contact, Major General Vladimir “Korch” Korchnol, has provided the U.S. with amazing intel for over 15 years. But after Nate gets fingered by the KGB, the US has no choice but to send him on some meaningless mission in Greece.

In the meantime, the Russians now know that one of them has been feeding information to Nash. They just don’t know who yet. This is why the Russians send their best honeytrap, Dom, to Greece, to see if she can get Nash to give up some clues as to who the mole might be.

After a lot of surveillance, Dom makes her move, and of course Nash instantly falls for her. She’s a honeytrap for goodness sakes! The problem is, Dom falls for him too! We then cut back and forth between their romance and the Russian team back in Moscow getting closer and closer to discovering that Korch is the mole. Will Nash find out he’s being honeytrapped in time to save his buddy? Or will poor Korch become Korch meat?

I think they have a good movie in Red Sparrow. But they haven’t found it yet in this script. Here’s the thing you want to keep in mind whenever you’re writing a spy romance. Are you ready?

THEY’RE ALL THE FUCKING SAME!!!!!!

It’s a good setup. Don’t get me wrong. You have two people who are in love with each other. But either one or both parties don’t know the other is a spy. And that dramatic irony adds a level of excitement to the romance that a basic romance just can’t compete with. So that’s great.

But we’ve seeeeeeen it already. We’ve seen it so many damn times. So what’s the difference with your spy romance? What makes yours a “must see movie?”

The thing with Red Sparrow is they have the answer. And yet they ignored it. There’s a throwaway line late in the script where they’re telling Nash that Dom is a honeypot, and how she’s tricked him. And he’s like, “No, she loves me. I saw it in her eyes.” And the guy’s like, “Do you know what kind of schooling they put these girls through? Their job is to make it seem like they love you.”

THAT. MY FRIENDS. IS YOUR MOVIE.

The implication here is that they make these spies irresistible, from how they interact with you, to giving you the most amazing sexual experiences you’ve ever had x1000. We’ve never seen these schools in this kind of movie before. We needed to see that. Teaching this girl, at a young age, things as complicated as every sexual move to make a man obsessed with you.

And not just because sex sells but so we understand who this character is when she meets Nash. We’ve seen her grow up in this horrid lifeless awful school designed to turn her into a sexual object, designed to turn her into someone with zero feelings, to never get attached to the mark.

Instead, we get a throwaway line and a halfway decent story about a best friend whose double-spy status might get revealed.

I’m sorry but I’ve seen that movie before. Dozens of times. Not enough writers ask themselves that question: WHAT AM I GOING TO DO THAT’S DIFFERENT?

I’m not saying you have to come up with the most amazing perfect story answer. But just by ASKING the question, you up the chances significantly that you’re going to write something that feels different from what others have written in the past.

Another thing I couldn’t stop thinking during this script was “faster, faster, faster.” The story needed to move faster. After the opening scene, we don’t see Dom again until page 28. And after that, we don’t see Dom and Nash meet til the midpoint. In my head, I’m thinking, “Come on, we can hit those plot points so much sooner.”

But then I remembered that sometimes, it isn’t that the plot points aren’t being hit fast enough. It’s that the story in between the plot points isn’t interesting enough. That can fuck with you when you’re writing, especially when you’re starting out. Because you need to figure out which is the real problem. Do I need to write faster? Or do I need to write better?

And the more I thought about it, the more I realized it wasn’t the slow-to-come plot points. It was the plot itself. Once you recognize that, you can start pinpointing what’s making the story weak.

Once I switched over from “faster” to “better,” I noticed where the script went wrong. I mean the stakes alone are a huge issue. The stakes here are, basically, Korch not getting caught as a double spy. That’s a nice subplot. But it shouldn’t be the main set of stakes driving a movie set in the Cold War involving the U.S. and Russia. The threat of nuclear fucking war needs to be part of the stakes. I liked Korch. But I don’t think Korch is as big of a deal as New York getting blown up.

Now, obviously, this is not a final draft. So I’m not criticizing this project definitively. In fact, I’m betting they’ve had these exact same conversations. But I think it’s a good screenwriting lesson to keep in mind for sure.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Is your script moving along fast enough? And if it isn’t, is it because your major plot points are taking too long to arrive or because your story itself needs to be more compelling?

THE WINNER HAS BEEN ANNOUNCED BELOW

SEMI-FINALS BABY!!!

The Final Four. March Madness. The Fearsome Foursome.

Down from over 500 entries, these four scripts are all that remain. Today’s scripts had to scratch and claw their way to this semi-final, each winning by less than 2 votes. I can only imagine what will happen this weekend.

A recap for those of you unfamiliar with the tournament. The first round went for 8 weeks, with you, the readers, voting for the best script each week. Those 8 winning scripts, plus 4 wild-cards, competed in the Quarterfinals. The 4 winning scripts from each quarterfinal are now competing in the semis, which is this week and next week.

Here’s how voting works. Read as much from each script as you can then vote in the comments section which script you think deserves to advance to the FINALS. Please explain why you voted for the script. It lets us know that you read the screenplay.

Today’s writers have new drafts. I’ll let them discuss the changes in the comments. Voting closes at 10pm Pacific Time Sunday evening.

#1 SEED

Title: The Savage

Writer: Chris Ryan Yeazel

Genre: Historical Biography

Logline: The incredible true story of Squanto, the Patuxet Indian who was kidnapped from the Americas as a child and who then spent his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that leads to one of the most significant events in American history.

WILD-CARD

Title: Cratchit

Writer: Katherine Botts

Genre: Mystery & Suspense/Fantasy/Horror

Logline: “A Christmas Carol” reimagined, told from the point of view of Bob Cratchit as he and Ebenezer Scrooge race to track down Jacob Marley’s killer — the same killer who now targets Scrooge as well as Cratchit’s son, Tiny Tim.

WINNER OF SEMIFINAL WEEEK 1: The Savage by Chris Ryan Yeazel! Congrats to Katherine, whose script was probably the hardest working in the tournament. Every time you thought it was out, she’d kill it with a rewrite and it’d be right back in contention. And, of course, congrats to Chris, whose #1 seeded script is like the Duke of March Madness. A powerhouse every time up. We’ll see who he’s going up against in the finals next week. Seeya then!!!

It’s 2017. You’re wondering what you should write. I’ve got good news. I’M GOING TO TELL YOU! There isn’t a person on this planet who knows what screenplays Hollywood’s buying better than me (it’s the new year, let me hyperbolize). But seriously, we know that Hollywood currently hates spec scripts. And who can blame them. The last three major spec sales (Collateral Beauty, Allied, Passengers), all underperformed this winter. If they had it their way, everything would be IP from this point forward.

But fear not! There are still plenty of script options a screenwriter can write and still sell. That’s what today’s article is about. I’m going to give you ten PROVEN genres that Hollywood will eagerly snatch up as long as you deliver the goods. Are you ready? Start taking notes. Cause this article is going to change your life!

Biopic – The biopic is still chugging along. Why? Simple. A-list actors are no longer needed to drive major tentpoles. Those A-list actors had to go somewhere to stay relevant. Enter the biopic, where they get to play famous historical figures and earn Oscar nominations. Who wouldn’t sign up for that? However, keep in mind that this genre is getting crowded. Everyone’s writing in it. So make sure you’re not phoning it in (i.e. don’t research your subject on Wikipedia). Find a unique and interesting way to tell the story so your biopic stands out from the rest!

True Story – This is the fastest growing spec genre out there and, in a way, the biopic’s little brother. But unlike a biopic, the subject doesn’t have to be super-famous. They need only have been involved in a fascinating true-life story. I’ve always wanted to write the real life story of Roswell (not the tin-foil hat version, but one based on facts and real interviews from those involved). Find that true story that you find fascinating, like yesterday’s David Steeves survival tale. Or the infamous “Astronaut Diaper” story chronicled in Pale Blue Dot. Or even the freaky tale about the woman who went crazy at that Los Angeles hotel and ended up in the water supply. So many great real life stories to choose from.

Female-Driven Anything – Ghostbusters didn’t deter Hollywood from their infatuation with female-driven fare. They want more female led films, both fiction and non-fiction alike. Action and comedy are the sweet spots because audiences pay the most for ass-kicking and laughs. But as long as you’ve got a great idea with a female in the lead, you should be good.

Budget-Conscious Action Spec with Franchise Potential – Action will never die. It’s the only genre that will play well in every single country it’s shown. The tough thing about action is finding an idea that hasn’t already been done before. John Wick’s secret society hitman world was cool. And while I didn’t like The Accountant, its non-traditional main character made for a unique take on the action genre. Also, you want to think franchise. So don’t make the film too self-contained. It should hint at bigger things to come. Also, don’t blow the roof off the doors with your budget. In order for something non-IP to get made, the first film will need to come in at a price, probably between 60-70 million. If the movie does well, the franchise begins, baby.

Horror Spec – The horror space is THE most competitive genre of them all. Horror has the biggest cost-to-potential-profit margin of any genre out there. A 2 million dollar film can pull in 100 million at the box office. No other genre even comes close to that kind of upside. For that reason, don’t give me another movie about zombies in the forest. You have to be unique. You have to find another way in. A good comp is A Cure for Wellness, the new horror film coming out from Gore Verbinski. It doesn’t quite feel like something we’ve seen in the horror genre before.

A spec in the superhero universe that isn’t about traditional superheroes – Newsflash. Hollywood is obsessed with superheroes. However, you don’t have access to the millions of dollars required to purchase famous superhero characters and write about them. Therefore, get creative. Find a superhero idea that’s not quite about superheroes. For example, a team of famous superheroes suddenly lose their powers and must integrate into society as normal people for the first time in their lives (think a famous boy band after the glitz and glamour is all gone). Something like that, where you’re coming at the genre from a different angle. Hmm, that’s actually a good idea. Maybe I’ll write that.

A “Voice” Spec – If people always tell you that you have a unique perspective of the world, or you see things in a different way, consider writing a script that highlights your voice. The great thing about writing a “voice” script is that you don’t have to write about anything exceptional. Your VOICE is the exceptional part. You can write about a guy with a shitty job, as long as you give us a perspective on guys with shitty jobs that we haven’t seen before. One note: Vocie-y writers go off the reservation too often. Voice is good, but you still need a story that goes somewhere, or explores something universal. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind was a very voice-y script, but it was exploring something universal – our fear of getting hurt, our struggles to overcome our past. It wasn’t the dreaded “rambling voice,” which is where bad voice scripts go badder.

Swords and Sandals Spec – I’m always looking for that genre that’s traditionally done well at the box office but hasn’t had a hit in awhile. The last swords and sandals hit was the Pirates movies. But the Pirates movies have become stale. I think a good swords and sandals script has the potential to explode onto the market. One note: HUMOR. I believe the reason Pirates did well while the recent Gods of Egypt did not was how well-done the humor was in Pirates. In fact, I was watching The Princess Bride the other day and thinking, “Someone needs to write the next Princess Bride!” A self-referential comedic swords and sandals movie? Start counting your money now.

A Forward-Thinking Spec – Our world is changing faster than it ever has before. Instagram, Uber, Fake News, Fake lives on Facebook, self-driving cars, our every movement being tracked, phone addiction, life disconnection — All of these things are dramatic elements that could be integrated into your next screenplay. Because if you’re writing a movie that could’ve been written in 1996, or even 2006, it’s probably not going to feel fresh. A comedy about what would happen to millennials if the internet went down for a week. I’d go see that. Shit, that’s another good idea. Why am I giving these away?

That Weird Idea You Have – This is actually the best time to write something weird, since the entire spec market has become so homogenized. There’s never been a time in history where more of the same hasn’t been peddled to film audiences. Your weird idea is going to stand out so much more than it did in the past. The weird idea spec may not sell, but like a good voice spec, it can catapult you into the industry and get you tons of work.

Genre: Drama – True Story

Premise: During the Cold War, a crashed pilot becomes a hero after surviving 54 days in the wild, only to see his heroism disintegrate when details of his survival come into question.

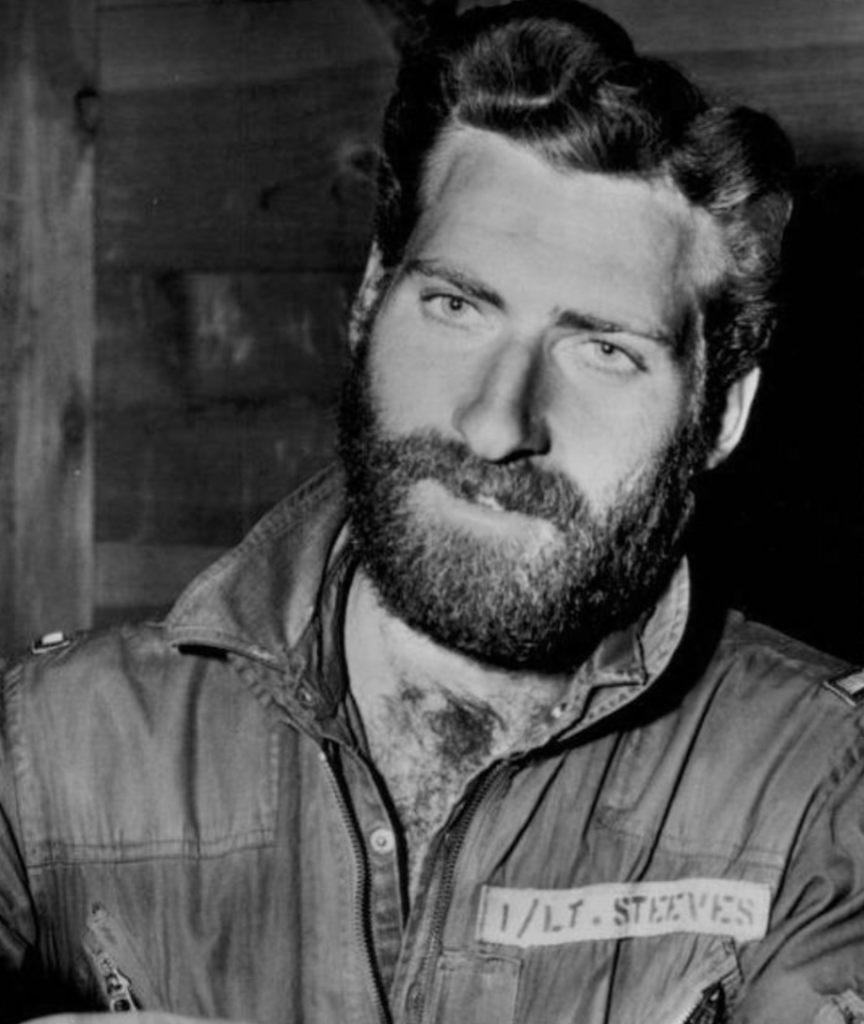

About: I’m not going to make a definitive statement here, because I don’t know why Parter and Hillborn wrote this script. But if you put a gun to my head, I’d guess that they saw a picture of the story’s subject, David Steeves, realized he looked EXACTLY like Bradley Cooper, and wrote the script figuring it’d be a formality to get Cooper to sign on. Also, part of their genius was to PLACE THE PICTURE I INCLUDED BELOW AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SCREENPLAY. Think they didn’t know that producers would alert Cooper to the resemblance? This script finished in the middle of the pack on the most recent Black List.

Writers: Evan Parter and Paul Hilborn

Details: 130 pages

If you want to know what Hollywood’s buying, all you have to do is look through 2016’s Black List. The list is dominated by four categories…

Biopic.

True Story.

Female-driven action movie.

Female-driven comedy movie.

I’ve already made my opinion known on this. I’d prefer something original, something different. But if you’re someone who surfs with the trends, you’ll want to write in one of these genres.

Today’s script goes with choice number 2 and follows David Steeves, a Cold War Air Force pilot who emerged from the Sierra Mountains after being presumed dead for 54 days, after his jet had crashed.

If you thought Sully was a big deal, Steeves became an instant national sensation. He had the looks, the beautiful eyes, and that glorious beard. That beard alone sold headlines.

So big was Steeves that the Post paid him 10 grand for the exclusive rights to his survival story. The man assigned to the story was Clay Blair Jr, a 30-something journalist new at the Post with plans to shake the newspaper up.

As Blair interviews Steeves about his story, we intermittently flash back to Steeves’ perilous journey, most of which hinged on him finding a shack in the middle of nowhere. He used that as his home base, and would’ve starved to death had he not come across it.

At first enamored with Steeves, Blair begins to see little gaps in his story, particularly regarding Steeves’ crashed jet, which was never found. A narrative begins forming that Steeves may have hoaxed his survival story to cover up that he’d sold his jet to the Russians.

The problem with Steeves is that he was far from the model citizen. A drunk and a womanizer, Steeves would routinely cheat on his wife. This painted a picture of a man who built a life around deceit. If he could deceive his wife, why couldn’t he deceive the nation? When Blair decides to cancel the story, the nation swarms in, wanting to know why, and that’s when Steeve’s story, and his life, really begin to fall apart.

If you forced me to pick between the above four trends, I would pick ‘true story’ without hesitation. It allows you to cherry pick a superb story. But more importantly, if you can find a killer true story, it does the work for you. You don’t have to be a great screenwriter to pull it off. You just need to know what you’re doing and let the story write itself.

Think about it. One of the hardest things about writing fiction is when you get to page 50 (or 60 or 70) and run out of story. With a true story, you know what happens ahead of time and can structure the script out accordingly.

A biopic, by comparison, requires a ton of skill, since you have to shape an entire person’s life into two hours, not to mention make it dramatic and entertaining. Since there’s a lot of dead time in a person’s life, it gets tricky figuring out what to include and what to ditch.

This is why Kings Canyon works. A man becomes a hero based on a lie. And both the “hoax” and the “lie” are highly dramatically compelling. That’s what you’re looking for when you’re trying to find a true story. Are its key plot points HIGHLY DRAMATICALLY COMPELLING?

For shits and giggles, let’s pretend this was a real life story about a man who stole $1000 from his employer, then was brought into his boss’s office where he was told they’d caught him. He then had to prove his innocence. Is there drama in that scenario? Sure. Is it HIGH DRAMA? No. The stakes are tiny. With Kings Canyon, you have a man who potentially sold military secrets to our country’s biggest enemy during a time when we all thought a nuclear war with that country was imminent. That’s high drama.

But there are some issues. Because we can’t tell the audience what Steeves is hiding for most of the movie, we’re only ever subjected to his surface. When he’s with his wife, we’re never privy to what he’s thinking. Even in the flashbacks, we only see Steeves’ struggle to survive. We don’t get inside of him.

I would argue that there are 4 other characters we know better than Steeves through the first half of the screenplay. Parter and Hillborn seem to realize this was a problem, and therefore shift the main character role over to Blair. He’s the one with the goal anyway (find the real story), so it makes sense.

But if you’re writing a movie about what happened to someone, are we ever going to feel satisfied if we don’t get to know that someone? Once the “lie” is exposed, Steeves is finally able to come alive as he fights for his dignity. But it’s a long wait, and he’s only active for the final act.

Regardless of that, the script works because the entire thing is a ticking time bomb slash mystery. We know the truth is going to come out sooner or later, and we also want to know what that truth is. As long as you have a compelling question driving your narrative, it’s impossible for your reader to stop reading.

By far the script’s most powerful engine is that of its flashback structure. As the story unfolds, we’re told more and more often that Steeves is a fraud who perpetuated a hoax. However, every time we flash back, even deep into the screenplay, Steeves is in the wild, clearly injured, and clearly trying to survive.

That contrast only deepens our curiosity. If there’s a hoax, what is it? Because it isn’t that Steeves made up his tale of survival.

I also thought the ending was great. There are a couple of late story twists that make you feel like the journey was worth it. So many times you read scripts with these inevitable endings. Like Rogue One. We know the ending at the beginning, so there’s only so much satisfaction we can gain once we get there. Kings Canyon not only throws you for a couple of loops, but it makes you think long and hard about the media-obsessed culture we live in.

I have a feeling they’re going to have a hard time getting Cooper or an actor of his caliber to play Steeves, only because the actor doesn’t have much acting to do for the majority of the story besides look happy. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe they’ll be drawn to the survival scenes so much that they’re willing to do nothing for the first 3/4 of the present-day narrative. We’ll see. Whatever the case, this screenplay rocked.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I don’t know if this is a lesson so much as an observation. But I loved how the flashback structure didn’t match up with the present-day narrative (the present is saying he’s a hoaxer, but the flashbacks are saying he’s telling the truth). That alone kept me fascinated throughout Kings Canyon. So maybe our lesson is “contrast between flashbacks and present day creates curiosity?” What I do know is that when your flashbacks tell us exactly what we’re being told in the present, they’re boring as shit. So definitely don’t write your flashbacks that way!