Note: I screwed up with the Scriptshadow 250 Top 5 Announcement. Monday, as we Americans know, is a major holiday (Memorial Day). So we’re going to move that announcement to Wednesday instead. Sorry about that!

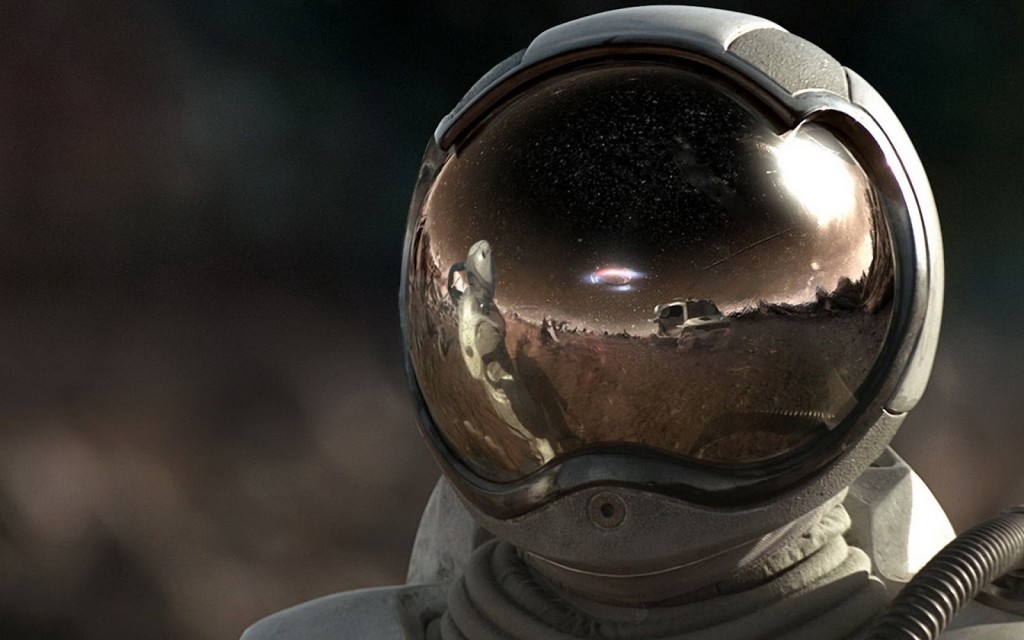

Genre: Somnium

Logline (from writer): A loyal astronaut, scheduled to be on the first mission to Mars, begins having terrifying dreams of the mission going wrong. Then, when the mission is sabotaged, he finds himself the prime suspect.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I’ve been writing for three years now, my script Jack Curious is in the Scriptshadow top 25 at the moment. This script is the script I wrote to teach myself the craft, and while it made the quarterfinals of the Big Break Contest and connected me with some cool people, it’s been sitting on the shelf for the last two years. I’d love the opportunity, with the help of the SS community, to pull it apart and work out how to make it better. I also have most of the budget together to make my narrative feature directing debut (I’ve only done docos so far), and I’m wondering if this could be the script to do it with.

Writer: Bryce McLellan

Details: 109 pages

We’re seeing a lot of Mars projects these days. We had The Martian. There’s that new weird Mars teenage love story (that I reviewed a few years back and was convinced would never see the light of day). There’s a Zachary Quinto movie I just learned about called Passage to Mars that for some reason takes place in Antarctica. There’s the Deadpool writers next sorta-Mars movie called “Life.” There’s “Approach The Unknown,” about a single manned Mars Mission. There’s one of my favorite amateur scripts submitted to the site, The Only Lemon Tree on Mars. And if you want to get really technical, they’re thinking about making a sequel to Veronica Mars.

What does this mean?

Hell if I know.

People have a galactic hard-on for red dirt?

I guess if we want to get into it, there’s something to be said for understanding where the hot topics are. Because once you know you’re playing in the same sandbox as everyone else, you have to decide if you can build a better sandcastle than them. If all you’re going to do is fill up your Big Gulp cup with goopy sand and flip it around four times and call it a day, your sandcastle probably won’t be able to compete with the next guy’s.

That’s why I recommend staying away from the hot subject matter. If everyone’s writing about Mars, write about Neptune. Or Uranus. Heh heh. Heh heh. “Uranus.” However, since we can’t go back in time and warn Bryce about this, we’ll have to see if he’s pulled off Plan B: finding a new angle into a Mars story.

The year is 2050 or so. Sam obtained the Mars Mission astronaut job when one of the other astronauts went crazy. I guess being picked for the first mission to Mars can be a bit anxiety-inducing for some. Joining Sam will be the Buzz Aldrin-like Jack and the smart-as-a-whip, Connie.

The American-led launch is competing against a similarly constructed Chinese launch, and just like when two Hollywood studios get the same idea at the same time, instead of joining forces and creating the best launch possible, they waste a lot of money to win the race by a few weeks!

And then Sam starts experiencing nightmares. They’re flying to Mars, their ship disintegrates, he lands on the surface with a thud. And then there are the winds. Sam can’t stop having nightmares about those horrifying 200 mile an hour Mars windstorms.

Meanwhile, as we move closer to launch, we cut back in time six months, where we learn that Sam’s wife, Kate, was pregnant. Since she’s not pregnant in the present, and we don’t see any kids around, we get the sense that that situation didn’t end well. And subsequent flashbacks will confirm that.

When a fire on the shuttle sets the launch date back a few months, people within this NASA-like operation begin to suspect that someone’s working for the Chinese, possibly sabotaging the mission so that China can launch first.

The big question is: Is it Sam? A lot of people think so. And with Sam’s nightmares getting worse, with his brain starting to break down, not even he’s sure anymore.

Let’s start with the good news. This is NOT like other sandcastles. And I should’ve known that since Jack Curious, Bryce’s Top 25 Scriptshadow 250 script, is anything but normal.

However, I think Somnium suffers from the flip side of things. Have we deconstructed storytelling TOO MUCH here? Is this “too indie?” Is “too indie” even a thing? I think so. But I know a lot of you don’t.

Let’s start with the flashbacks. Whenever I look at flashbacks, I ask the question, “Are they necessary?” 99% of the time, they’re not. But when they are, they’re usually used in a pattern. And that’s because the writer is using them to tell a separate story in the past, that, if told well, can actually be as interesting as the present story.

I’m not sure this flashback story passed that test. It’s about a woman losing her child. And the thing was, we already knew she lost the child. Like I pointed out, we didn’t see any kid in the present. And she wasn’t pregnant in the present. So obviously she had to have lost the baby.

So why is it important that I see that for myself? Why can’t that just be backstory and not a series of flashbacks? I don’t have a good answer for that, and therefore I’d argue the flashbacks weren’t necessary.

Next up is the way the plot was designed. And Bryce takes a HUGE chance here. I give him credit for that. But let’s look at this logically…

Remember the movie, National Lampoon’s Vacation? The original one with Chevy Chase? Remember what they were trying to do? Get to Wally World, right? Well imagine if that movie wasn’t about actually going to Wally World, but rather about getting in the car that would take them to Wally World.

That’s kind of what this felt like to me. And I’m not saying that the destination has to always be the biggest thing possible. But when you dangle something as exciting as Mars in front of the viewer, and then you tell them we’re not even going to see Mars in the movie…it’s kind of like a literary version of blueballs. We feel cheated, right?

Now, to Bryce’s credit, Somnium starts to get a lot better in its second half. The main reason for that is the China mystery. Are they sabotaging the launch? And if they are, is Sam involved? That was the plot point that drew me back into the story after I got pissed when I realized we wouldn’t be going to Mars.

I also liked the mystery of Sam getting fed these suspicious pills. It added another layer to the sabotage mystery. Maybe someone was manipulating Sam to sabotage the launch without his knowledge?

Unfortunately, none of this stuff gets paid off in a satisfying way. It was paid off in that vague “you decide” way. And I’ve never been a fan of that.

If I were Bryce, I would introduce the Chinese sabotage mystery much earlier in the script. Make it a major plot point. Because if there’s one thing this script lacks, it’s structure. It’s plot. It’s built on this wishy-washy foundation of flashbacks and character uncertainty. It needs a plot that’s more definable.

Then use the flashbacks as a decoy. We think they’re about Kate losing the baby. But through them, we reveal that Sam IS actually involved with the Chinese, therefore making the past plot an official part of the story as opposed to just character backstory.

The more you structure Somnium, the better it’s going to be. And I think Bryce is a good writer. So he can pull it off. But it’s going to require work.

Script link: Somnium

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Flashbacks JUST FOR CHARACTER BACKSTORY are usually a bad idea. If you’re going to use flashbacks, use them to ADD TO THE PLOT. We should learn cool things in the flashback that we couldn’t have learned in the present. And these things need to AFFECT THE PLOT. That’s one of the only times flashbacks can be an asset.

Okay guys. So last week, we got up to page 40. At least I hope we did. Since this is screenwriting, I’m sure a spoon full of you made up reasons to watch 15 movies in the genre you’re writing as part of your “research,” cough cough.

Look, I’m not going to pretend like that’s never happened to me. Sometimes we are faced with the inability to come up with creative ideas and when that happens we’ll look for anything to do other than write. But if you’re going to get this script done on time, you need to throw away that judgement voice in your head and get those pages down.

Ultimately, you want to work in this business, right? Well guess what happens when you have an assignment due? Do you think the people paying you 500k are going to be like, “Oh yeah, just get it to me whenever inspiration strikes.” Yeah, unless you love giving studios reasons to void a contract, I’d suggest getting used to deadlines. Consider this practice for the big leagues.

We are now inside those 50 or so pages that many refer to as “the jungle,” because it’s where screenplays wander into and never come back out. Luckily, we outlined ahead of time, we did character work ahead of time, which means this section should be easier for you than for the guy who thought he’d write a script and “see where it goes.”

This week, we’re writing to the midpoint, which should be somewhere between pages 55 and 60. The midpoint is where you’ll be throwing a game-changer of a moment into your story. Maybe it’s plot related. Maybe it’s character related. It could be a major reveal, a major reversal. But that’s not what we’re going to be talking about today. Because we still have to write 5-8 scenes JUST TO GET US TO THAT POINT.

In order to understand what those scenes should be, we need to remind ourselves what the second act is and why it’s so difficult. The reason the second act is so tricky is because it’s the least definable section of the story. The first act is obvious in its intent. It’s SETTING THINGS UP. The third act is obvious in its intent. It’s CONCLUDING THINGS. That gives both acts AN IDENTITY.

Think about that for a second. Because it’s the MAIN REASON why the second act is such a fluckstercuck. Screenwriters literally have no idea what the intent of the act is. And what happens when you write without intent? Your story goes fucking nowhere, that’s what happens. So for us to even approach a strong second act, we have to define the act’s intent.

The second act’s intent is: CONFLICT

If you remember that the goal of this act is to create and sustain conflict, you should be all right.

Now, there are three areas of conflict you’ll be exploring…

Plot obstacles.

Conflict between your hero and others.

Conflict within your hero.

Let’s start with plot obstacles because it’s the easiest one. But you have to understand something first. If you haven’t set up a goal for your hero to achieve, you cannot place obstacles in front of anything. This is why goal-less character scripts are usually so boring. By the very nature of not having an objective, you can’t place anything (obstacles) in the way of that objective. That’s why I go on and on so much about goals. Because it’s hard to make a plot interesting if you don’t have anything to disrupt it.

Can it be done? Yes. But only if you are a MASTER at character development and character conflict. Which means you have to get these next two things right.

Conflict between your hero and others is the process of coming up with an “issue” between two characters and having those characters butt heads over that issue throughout the script. Take Lester Burnham in American Beauty. The very first element of conflict brought up in that movie is that Lester’s wife, Carolyn, has tuned the fuck out of the relationship. She doesn’t respect him anymore. So every time we see those two together, we can explore that lack of respect. That’s the IDENTITY of their conflict.

Where conflict between your hero and others gets tricky is in the variety that’s required. You need to come up with different types of conflict between different characters. So to use American Beauty as an example again, Lester’s daughter, Jane, and him just aren’t friends anymore. They don’t talk to each other. The IDENTITY of that conflict is different from one person not respecting another person.

The point is, a large portion of the second act will be used to explore conflict between characters. This will be less so in action and thriller scripts and more so in character pieces and dramas. But it will be there in some form or another in EVERY SCRIPT.

This brings us to our last form of conflict – conflict WITHIN the hero. This is the hardest form of conflict to execute because it’s difficult to take something internal and explore it externally. That’s why I always encourage writers to consider this when coming up with their hero’s flaw. There are certain internal flaws that are easier to explore externally than others.

Selfishness is one of them, obviously. It’s easy to come up with scenes where your hero picks himself over others. Lack of belief in one’s self is another. Being stubborn. Not living in the moment. Puts work over family.

These are all (more or less) internal flaws that can be explored externally. You achieve this by putting your character into repeated situations that directly challenge this flaw. So if you have a character who’s stubborn, like, say, Gene Hackman as the coach in the basketball movie, Hoosiers, you show him at his first practice with a group of townspeople who show up and say that they believe the practice should be run THEIR way. This is a direct assault on our main character’s flaw. Which means we not only get to explore his flaw, but we get to infuse a scene with CONFLICT. And as you now know, that’s the name of the game in the second act.

If you want to get into some advanced shit, make sure you’re sitting. Because things are about to get all AP English up in this mug. If you want to explore character and conflict in a truly impactful way, each subsequent “attack” on your hero’s flaw should be more credible than the last. So in the scene above, of course Gene Hackman’s going to tell a bunch of a-holes to screw off when they invade his practice. But later on, when the woman Hackman is falling for, a teacher, starts telling him that it’s more important for these kids to get an education than spend every waking moment practicing basketball, now his stubbornness is really getting tested. Because there’s more at stake by telling this person no.

Finally, the second act is a big place. So while I’m promoting a structural approach to it, I still want you to be creative. Follow your imagination. Try things out. You can always pull it back in if it gets too crazy. But I don’t want your script to feel like ScriptBot4000. It still needs a heart. It still needs to breathe. So make sure you’re still having fun.

Good luck, guys. You’re almost halfway home!

Genre: Action

Premise: When Air Force One is shot down in South America by terrorists, the female president of the United States must be rescued by a local Seal Team that isn’t too fond of her.

About: This script sold last year to Millennium Films and was written by Gregory Allen Howard, who wrote Remember The Titans as well as did some work on “Ali.” Howard is trying to move away from more serious stuff and re-brand himself as an action writer. Looks like it’s working out so far!

Writer: Gregory Allen Howard

Details: 122 pages – 1st draft

Hollywood. Loves. Action.

They love it.

It is the genre that will never die because it PLAYS EVERYWHERE. And in an ever-expanding global market, it gives studios the best chance for a big return on their investment.

Strangely, many of these action specs that get purchased never get made unless they stay closer to the action-thriller genre, which is a little more focused, less grandiose – stuff like Taken. These big idea action specs are having trouble getting green lights, and I have some theories on why which I’ll share in a moment. First, let’s check out the plot here.

Karen Morgan is the tough-as-nails president of the United States. When she learns that Hakim Ibn Al-Libi, a top Al-Queda terrorist, is in Somalia, she orders a local American military outfit to grab him. Led by tougher-than-nails Commander Bobby Lee, the Americans Zero Dark 31 him up.

Unfortunately, they find out that the President has decided to swap Hakim back for one of their own. Lee is pissed, but since those decisions are way above his pay grade, he rolls with it. That is until a week later when Lee’s son is killed in a suicide bombing… by Hakim!

Meanwhile, President Morgan is heading down to Ecuador for some conference, but as soon as they land, they’re attacked by the local military… who just so happens to be led… by Hakim! Air Force One is able to take off, but is shot down immediately. President Morgan is able to eject via the special Air Force One “escape pod,” but now finds herself in the dangerous jungles of nearby Columbia, with a quickly approaching Hakim.

Back in the U.S., they learn that the closest team to extract the president is… Bobby Lee’s team! And therein lies the irony. The guy whose son was killed because of a direct order by the president is now tasked with saving the president!

The rest of the script plays out like a game of cat and mouse, with some really big cats and some really gnarly mice. In classic early 90s action form, we have our control room, our president and her Seal Team, the pursuing baddies, and the nearby extraction ship. Will our female prez make it to safety? That will be up to a still simmering Bobby Lee, who doesn’t take too kindly to presidents killing his son.

Okay, before we get into my thoughts on action specs, I first have to regurgitate a rant.

I hate reading these presidential scripts.

There are at least 25 characters (joints of chiefs of staff, CIA directors of staff, Defense Secretary of Staff) you have to keep track of, and you have no idea which ones are One-Scene Johnnies and which ones are sticking around for the long haul, which means you’re spending all this mental energy on remembering people who don’t matter.

The worst are these 3-characters-introduced-in-a-single-paragraph moments. You might as well hold a screenwriting funeral for those characters because there’s no way in hell the reader is going to remember them. All of this gives the script more of a homework assignment feel as opposed to an entertaining piece of fiction.

To some degree, I understand that this is necessary. To feel authentic, you need a lot of the periphery government people around the president. But as a writer, it’s your job to be aware of that problem so you can curb it whenever possible. For example, if there are any single-scene characters, do you really need to give them a name? A reader’s brain only has so much space to fill up. You don’t want to gum it up with unimportant people or information.

Story first story first story first.

The priority is always writing the most entertaining story. You then go back and include the minimum plot, logistics, and exposition you can get away with. Cause nobody gives a shit about any of that if they’re not entertained.

Now this next issue may be because this is an early draft, so keep that in mind, but I don’t like my action scripts to have a ton of 3-4 line paragraphs like Hunt Capture Kill did. I like things to be a little more cut-up, spaced out. Remember that how something is read has to feel like how it will be watched. Action moves faster than any other genre with the exception of maybe comedy. So the paragraph structure should reflect that. Keep things closer to 2 lines each, with a 3-liner every so often.

Now onto these modern-day action specs and where they go wrong.

I believe that too many action writers are attempting to resurrect the 80s action film. The thing is, that era is dead. That was a time when the your main character could pump out jokey one-liners every time he killed a man. For whatever reason, today’s audiences require a more believable vibe.

True, everything is cyclical, but just like fashion, you can’t bring it back in the exact same form. You have to find a way to modernize it. And these big concept 80s type specs feel more trapped in the past than they do reinvigorating it.

A successful example is Fast and Furious. We didn’t have any major drag-racing action movies back in the 80s. So that movie felt unique when it came out. And I happen to know that when producers talk about looking for scripts, “something like Fast and Furious” comes up a lot, because it’s a franchise starting film that doesn’t cost the studio an arm and leg to buy up any IP. It really is an ideal space for a spec screenwriter to write in.

With that said, I was open to hunting, capturing, and killing here. And one of my criteria for good action specs is: Do I see anything in the first act that I haven’t seen before in an action movie? Genre movies are easy to write if all you’re doing is rewriting your favorite scenes from previous genre movies. They’re a lot harder to write if you’re trying to be different. So I know if I see something different, I’m in good hands.

The setup here was very standard early 90s stuff. Get the terrorists, meet the government, set up meeting in Ecuador, plane goes down, team goes in. Where was a scene I hadn’t seen before?? The first time that happened was halfway into the script when our SEAL team comes across two hot bikini-clad Columbian women bathing in an isolated river who then take out some AK-47s and start shooting at them. However, I’m still not sure how that scene made sense. Does Al-Queda employ beautiful half-naked women in isolated parts of the jungle? Or were these two just really pissed off that someone was interrupting their daily swim?

I did like that the person charged with saving the president was someone who hated her. But the more I thought about this idea, the more I wondered if it would be better if the president was male and the person charged with saving him was a woman. Wouldn’t that be a more original (and interesting) take on this setup?

I don’t know. As I said already, this is a first draft. So maybe a lot of this gets sorted out later. But I was definitely hoping for more.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One-Scene Johnnies. Characters who are only in the script for one scene. Think long and hard before you name these characters. If you really truly think they only work with a name, name them. Otherwise, call them by something general (Waitress, Lieutenant) so as not to force the reader to remember someone meaningless.

What I learned 2: Whatever genre you’re writing in, make sure at least ONE of the scenes in your first act is something we haven’t seen before in that genre. If you can’t be original in your first act, why would I believe you could be original for the rest of the script? And really, you should be doing this with more than one scene. One scene is the absolute minimum.

Genre: Drama/Mystery

Premise: After a home invasion ends in the accidental murder of a mother, her young son is convinced that he knows who the killers are. Unfortunately, nobody believes him.

About: This is a script that the Coen Brothers wrote back in 2007, but it never made it into their production pile. Enter George Clooney, who ADORES the Coens. If they’ve got an available script floating around, you can bet your ass he’s going to read it. And apparently, he liked what he saw. Also, cause he’s George Clooney, he can get a killer cast. Suburbicon will star Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon, Julianne Moore, Josh Brolin, and Woody Harrelson.

Writers: Ethan and Joel Coen

Details: 113 page – March 27, 2007 draft

As some of you know, I have a love-hate relationship with the Coen Brothers. At times I believe they understand screenwriting better than any writers in Hollywood. They’re great at stripping plots down (usually focusing on a bag of money), populating their stories with unforgettable characters, and making unique choices.

But then they make movies like Inside Llewyn Davis, which seemed to breed boringness, or Hail, Caeser, which seemed so desperate to make up for that boringness, that it became boring in its anti-boringness. In many ways, the Coens are a victim of their unique voice. By the very nature of being so different, audiences aren’t always going to come along for the ride with you.

This time, the Coens are handing over directing duties to their star pupil, George Clooney. Clooney, who’s directed four movies so far, seems to want to take the Clint Eastwood approach to his career. He’s repeatedly said he’s uncomfortable with getting old onscreen, so I imagine we’ll soon see him exclusively behind the camera. Let’s check out what he’s working with this time around.

8 year-old Nicky Lodge hears his dad outside his bedroom door talking to an unfamiliar voice. When his father, Gardner, opens the door, he tells Nicky that a couple of men are here, and as long as we do what they say, they’ll leave us alone and everything will be all right.

So Nicky, Gardner, Gardner’s wheelchair-bound wife, Rose, and Rose’s sister (Nicky’s aunt), Margaret, are taken to the basement, tied up, and given chloroform. When Nicky wakes up, he’s at the hospital learning that his mother is dead.

Later, when Nicky, Gardener, and Margaret are brought in to a police line-up to identify the potential killers, Gardener strangely asks that Nicky leave the room. But Nicky is able to see the line-up through an ajar door. He also sees his father and aunt look directly at the men who killed his mother and tell the police that that’s not them.

That’s the first moment Nicky realizes something is wrong.

When he confronts his dad about the ordeal, his dad tells him that Nicky is simply misremembering. But the next day, when Nicky gets home from school early and sees his father and Margaret naked on the pool table, he knows something is seriously up.

Sensing that his son is onto them, Gardner enrolls him in boarding school, but before he can even begin to put that together, a suspicious insurance auditor comes around wanting some questions answered about Rose’s suspicious insurance policy. Oh, and let’s not forget the two guys who perpetrated the murder, who are tired of waiting for their payoff. Yeah, they show up as well.

It looks like whatever plan these two thought they’d pull off isn’t going to end the way they thought it would.

Every serious screenwriter needs to read the first scene of this script. It does five deadly important things right:

Starts the script off with a bang to grab the reader’s attention.

Approaches the scene in a unique way.

It’s intensely suspenseful.

It builds.

It holds tension throughout.

I’m lucky if I read a script where a writer is able to do one of these things right in an entire screenplay. To do all five in one scene shows why the Coens are two of the only people to win multiple screenwriting Oscars.

So let’s go into all of these in detail.

The first one’s obvious. I tell you guys to pull your reader in right away with your opening scene. Here, we open with a murder. Perfect.

The second is what sets the Coens apart from their competition. They’re really good at coming into scenes from a UNIQUE POINT-OF-VIEW. This gives what would otherwise be a been-there-done-that scenario a fresh angle. So instead of seeing the murder from the dad’s or the killers point-of-view, we see it from this kid’s point of view. And since Nicky isn’t sure what’s happening exactly, everything feels fresh and different.

Third is suspense. Remember, the best kind of suspense is to imply that something bad is going to happen, and then you draw it out for as long as you can. We know early that these men are up to no good. So everything that happens before the chloroform plays like gangbusters.

Fourth, the scene builds. A lot of writers want to jump into the climax right away. For example, we’d show the killers screaming and yelling and then gunshots would go off. That’s a really boring way to show a murder. Instead, we start off with Nicky being brought out of his bedroom, then downstairs. We then have a conversation in the living room. We then find out that we’re going downstairs. We then find out that we’re going to be tied up. We then find out that, person by person, we’re going to be given chloroform. Each “stage” or “level” is worse than the last. That’s how you build in a scene.

Finally, we have tension. I feel that too many writers go for instant gratification in a scene. They want to “burst the balloon” so-to-speak. Instead, pretend that your fingers are the only thing keeping the air in the balloon. Hold onto that opening AS TIGHT AS YOU CAN. Keep that tension throughout

Honestly, this first scene should be taught in film school.

And really, the majority of this script could be taught in film school. For example, what do I always say about funerals? DON’T PLAY THE OBVIOUS EMOTION in THE SCENE. Play any emotion BUT the expected one. So after the mother’s funeral, we don’t have Nicky telling his dad how much he misses mom, or a scene where the dad breaks down crying in the middle of the wake. We have Nicky walking with his weird uncle, who’s bitching about how lame the service was. The emotion he plays is ANGER, which works against the expected tone, and therefore makes for a good scene.

And the Coens can always find ways to add tension to scenes so that even the smallest ones have something going on in them. Because remember, the most boring scene you can write is two people sitting or standing across from each other in a generic location talking about whatever needs to be talked about in that scene.

Here, our two killers, Luis and Ira, are bus drivers. Luis, who’s working today, is avoiding Ira because Ira wants to put more pressure on Gardner to get their money sooner. So when Ira shows up on Luis’s route, he demands that Luis step outside for a talk. Luis reluctantly comes outside, and Ira tells him what he needs to tell him.

The scene works better because now you have 20 bus passengers popping out and saying, “Why the fuck are we stopped?” “This isn’t even a real stop.” This turns what could’ve been a boring scene (two people sitting or standing across from each other in a generic location) into an intense one. This is the kind of writing, guys, that top producers notice. They know that writers who know how to do this shit are good writers.

My only issue with Suburbicon was the ending. It came together too quickly. There’s a classic Coen Brothers scene where the insurance agent shows up and tells Gardner he’s onto him where I thought, “Ooh, this is about to get good,” then everything goes to shit quickly and before I knew it, I was at the end. It just felt like we needed more time to get there.

Still, this script shows why these guys are heads and tails above all the other screenwriters out there. Definitely check it out if you can.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The more helpless you can make your main character, the more compelling the drama will be. The reason this script is so intense is because our hero is 8 years old and powerless. Even though he knows who killed his mom, he can’t do anything about it, and that’s why we turn the pages. We’re hoping against all hope that he somehow finds a way. To understand why this works so well, switch 8 year-old Nicky out and replace him with a 30 year-old man. A 30 year old man would be able to solve this problem immediately. We’d feel very comfortable with him taking care of the problem. As you should know, “comfortable” in storytelling is the same thing as “boring.” One of the many reasons the Coens can rock the page.

What I learned 2: If something is obvious, you don’t need your character to say it. So let’s say a woman’s husband dies. You don’t then have the woman say, “I can’t believe he’s no longer here. I miss him so much.” Oh really? Wow, I never would’ve guessed that. If it’s obvious, the audience knows. You don’t need to have your character say it so that they get it. This is VERY common beginner screenwriter tell.

The box office is chirping, people.

It’s chirping at you now. Hopefully, you’re paying attention.

The top movie of the weekend was Angry Birds, which took in 39 million worms. This film represents everything that Hollywood wants in a project. Established IP. Something that can sell toys. Something that plays to all audiences.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t help the average screenwriter understand what they should be writing, since established IP is off-limits. If pushed for a lesson here, I’d say that the more age groups your screenplay plays to, the more appealing it will be to a producer, assuming it’s a good idea and well-written.

But what multi-demo genres are left that aren’t dominated by the IP market? I can think of three. Studios will always be looking for a good adventure script along the lines of Raiders of the Lost Ark. They’re always looking for that supernatural or sci-fi comedy type script (think MIB or Ghostbusters). And everyone’s STILL looking for the next Goonies, 25 years later. Kathleen Kennedy says that of the 30 huge movies she’s made, that’s still the one she gets asked about the most. So something in that vein is still available to spec writers. I would caution though that you better bring your A-Game cause I’ve read all the attempts from writers of these scripts and outside of Roundtable, they’re painfully generic. You have to find a new way into these ideas.

The second big release of the weekend is Neighbors 2, which brought in 21 million, along with some more relevant advice for screenwriters. Comedy still represents one of the best chances for an unknown screenwriter to break into the industry and earn millions of dollars quickly. Come up with a smart (preferably ironic) comedy idea, sell it, and when it does well, reap the benefits of its subsequent sequels.

That brings us to the most complicated major release of the weekend, The Nice Guys. The Nice Guys is the screenplay that serious screenwriters believe there should be more of. It doesn’t fit into any genre or even sub-genre. It’s unique. It’s fresh. But nobody went to see it, including, I’m betting, a lot of the screenwriters who say there need to be more movies like it.

This is the hypocrisy that bothers me about the anti-Hollywood crowd. They cry foul when their weird anti-narrative screenplay doesn’t get noticed. I then ask them if they’ve seen [latest low-profile indie movie] and their answer is almost universally “no.”

So if they’re not paying to see the few anti-Hollywood movies that DO make it through the system, why in the world would they expect anyone to do the same for their movie? It becomes painfully clear that they’re not supporting unique films. They’re supporting THEIR unique film.

This problem permeates a huge swath of the screenwriting community. They think they’re different, that they’re special, that their weird little script is somehow going to be the one that everybody goes to see. When a movie that has one of the biggest movie stars in the world, Ryan Gosling, promoting the hell out of it, and was still barely able to make 10 million dollars, you have to understand that THAT’S why studios are so terrified to take chances on offbeat little films like this.

I mean answer this question seriously. Would you have put up your money for The Nice Guys?

Another major spec release was last weekend’s Money Monster, a film that represents a key issue with the spec market at the moment, and why fewer and fewer of these movies are doing well. A spec script is meant to keep a reader’s attention from start to finish. There can’t be any slow parts.

This necessitates such things as a HUGE idea, tons of urgency, and heightened variables – all things designed to keep a bored reader awake. Unfortunately, this isn’t necessarily a recipe for a great film. A great film creates some sort of emotional connection with the audience.

And emotion requires things that lie in opposition to a reader-friendly script: Character development, relationship development, the occasional slowing down of the narrative. None of those things play well on the page unless you really know what you’re doing.

As a result, we get movies like Money Monster, which at one point in time would’ve had a 30 million dollar opening. Now, with a major effects-driven film to compete with every week, the script needs to do more than merely move. It needs to move the audience. And the “Max Landising” of this craft discourages against that.

The most successful spec story of the year is Cloverfield Lane (remember that it was originally a spec script before they turned it into a Cloverfield film). The 70 million dollar grossing contained horror flick managed to strike the perfect balance between a tight urgent story and characters with some actual meat to them. This allowed us to feel some emotion, which helped strike the perfect balance between “event” and “experience” so many spec screenplays lack these days.

Look, moving fast to please a reader while slowing down to move a reader is always going to be a challenge. You’re literally incorporating things that work in direct opposition to one another. But that’s why the screenwriters who carve out careers in this industry get paid so much, because they’re able to find that balance. Keep that in mind as you’re writing your “Scriptshadow Write a F%$&ing Screenplay” scripts.

Make sure to tune in next Monday as we’ll be revealing the Top 5 scripts in the Scriptshadow 250 Screenwriting Contest, held in conjunction with Grey Matter. We’ve already begun to contact the finalists. And for the winner, it’s probably going to change their lives. So can’t wait to finally share!