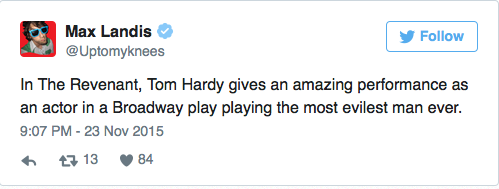

Guys, I’m too wrapped up in Thanksgiving duties to get anything up these next few days (fully expect to hear some jokes off of that unintentional phrasing). So I’ll leave you with some things to discuss, starting with Max Landis’s baffling decision to keep badmouthing his peers. Landis took to his favorite delivery device, Twitter, to tell the world that The Revenant (my old script review here) sucked, making fun of DiCaprio, Hardy, and Inarritu in the process. Is there anyone out there as confused by this as I am? I think Landis is operating on this belief that he’s “keeping it real.” And I suppose he is to a certain degree. But it’s a bad look when you’re attacking three of the most talented people in the industry while you’re putting out rotten turkeys like American Ultra and Victor Frankenstein. It’s kind of like the bat boy for the Seattle Mariners telling Derek Jeter his swing sucks. Wait til you get a jersey with your name on it before you start taking on the big boys.

There’s a subplot to all this. After Landis’s American Ultra bombed, he went on a Twitter rant (man, this guy likes Twitter) about how his movie failed because the public only wants to see established properties and IP. They refuse to take a chance on something new. So the fact that he’s now writing about one of the most famous characters of the last 100 years, Frankenstein, should warrant an interesting reaction if the movie doesn’t do well, especially in the wake of the movie he’s blasting, which is about as original as a Hollywood film gets.

Moving on, Thanksgiving is usually one of the better moviegoing weeks, as studios try to capitalize on families being in that holiday group-activity spirit. But I can’t say I’m too excited about this week’s offerings. Pixar’s The Good Dinosaur looks to be aimed directly at the Kids Aged 2-4 demographic. And The Danish Girl seems to be less about telling a story and more about winning an Oscar for its lead. The wild card is Creed, with Fruitvale Station director, Ryan Coogler, coming back to direct his star, Michael B. Jordan, again in this Rocky 6.5 vehicle. Deadline had a nice interview about Coogler pitching Stallone on himself as director before he’d even made a film (he would direct Fruitvale later). One of the best things about the interview was Coogler realizing, while shooting, that a key punch in one of the fight scenes didn’t look real enough and the dilemma posed by getting Jordan to take a real punch despite not legally being able to tell him to do so. In today’s Concussion-obsessed world, that turned out to be a risky ass move.

I have a couple of issues with this one though, despite the trailers looking solid. First, Rocky Balboa (or “Rocky 6”) was way overrated. Stallone tried to make it out to be him “correcting his wrong” with Rocky 5, and making something grittier and more in tune with the original film. That’s great. But why the hell would your main fight be an exhibition match?????? One of the first things we’re taught in screenwriting is STAKES. The stakes need to be high for the audience to care. And the climax? The big fight? It has to have the biggest stakes of them all. So why should we care about a freaking exhibition bout? Huge screenwriting fuck-up there. They needed to figure that out before going in front of the camera.

The second issue is that, from the trailers at least, Creed is propped up on a shaky foundation. Jordan plays Adonis Johnson, the son of Apollo Creed, who famously fought Rocky Balboa in the first two films (and was killed by Drago in the fourth!). Somehow, Adonis has never met his father. And grew up in an orphanage or something. So let me get this straight. The son of one of the richest boxers in history didn’t inherit a single dime from him? I’m guessing he’s maybe an illegitimate child then? Hmmm, I’m smelling a fish. Clearly, they know this series works best with an underdog hero. And the entitled son of one of the best boxers in the world isn’t underdog in any sense of the word. This forced them to pull out all the stops to turn someone who would obviously be famous to someone who was unknown, hence the “foster child” angle. Whenever I feel those screenwriting gears straining underneath the page – especially when it’s to keep a franchise alive – I get skeptical.

But hey, I hope I’m wrong. Unlike Landis’s Victor Frankenstein, which is coming in at 13% on Rotten Tomatoes, Creed is trending at 93%, a full 80 points higher.

So, I send the question out to you now. What do you think of all this? And what are you going to watch this weekend (doesn’t have to be anything I’ve mentioned)? Just a warning: I will automatically delete anyone who answers, “Jessica Jones.” (that’s a joke btw – though I will be watching you – oh yes, I will)

Oh, and if all of that bores you, tell me what you think of the new Captain America trailer! Tony’s maaaaa-aaad…

Genre: Noir/Super-hero

Premise: From Marvel – A female private eye with a dark past muscles through her daily routine while trying to overcome her demons.

About: This one has been heavily hyped by Netflix and Marvel the moment it was announced. The series comes to us in all its binge-y glory from the accomplished Melissa Rosenberg, who wrote ALL FIVE Twilight movies. Rosenberg has been trying to get this show on the air since 2010, when she brought it to the networks. It didn’t work out, leading to Netflix finally landing the project. Along with their “Daredevil” and another Marvel show coming later, the plan is to eventually bring all these shows together in one of those Marvel team-up things called, “The Defenders.” Based on what I saw with this show and also the petering second half of Daredevil’s first season, it’s a safe bet that I won’t be onboard for that one.

Creator: Melissa Rosenberg (based on the Marvel comic book series)

We’ve gotten to a dangerous place with TV shows. Nowadays, there are so many shows that the only way to get attention is to declare your show the single greatest show that’s ever existed in the history of television.

Before a single show has aired.

Rotten Tomatoes, with their fatally flawed TV rating system, isn’t helping matters, giving any show that isn’t The Goldbergs a 90% rating or higher.

But here’s the funny thing. Even THAT approach is starting to get old. So now marketers have to find a new way to get viewers interested. Jessica Jones may be the first show to institute a ‘greatest show ever’ declaration…

Before a single frame of film was shot.

I have been hearing about this show for a year now and with the supposed buzz surrounding it, you’d think they’d announced a Lost – Breaking Bad crossover series.

Based on the Marvel comic, Jessica Jones follows a private detective, Jessica Jones, at her job, which mainly consists of busting men cheating on their wives (go girl power!). She’s occasionally hired by a big company to dig up dirt on people – one of the many private detective been-there-done-that tropes that this show embraces.

In the pilot episode, Jessica’s hired by an older couple who believes their adult daughter’s been kidnapped by a cult. Jones looks into it, and realizes that the woman is in an abusive relationship. But not just any abusive relationship. An abusive relationship with JESSICA’S FORMER BOYFRIEND, the delicately named “Kilgrave.”

From here we hint at Jessica’s dark-disturbing past, which included dating Kilgrave, a mind-manipulator or some such. Jessica’s got PTSD from the relationship and realizes that getting this daughter out of the relationship will be near impossible. Because of the mind-control and all.

Meanwhile, we see Jessica occasionally do things like lift cars six inches off the ground, an apparent nod to her being a retired superhero, although you’re not going to get that information from the show. I had to look it up online.

While I only watched two episodes due to their dreadfulness, the show looks to want to build around this mind-manipulator Kilgrave making his way back into Jessica’s life, as well as Jessica’s new love interest, Luke Kage, a local bar owner who also has secret super powers. If you’re into all of this stuff, wonderful. I’ve never been more bored in my life.

Here’s my problem with Jessica Jones. For all the hoopla surrounding this show, it’s pretty freaking standard. You have a private eye (a formulaic staple of TV for 60 years) with a dark past (ooh, haven’t seen that before). The only real difference is that a) she can swear cause this is Netflix, b) they can be edgy cause this is Netflix and c) the superhero angle.

That last part would appear to be the unique draw, but through two episodes, all I’ve seen Jessica do is pick the back of a car up two feet. I guess that makes her a superhero? Strangely, six scenes later she can barely pull a 110-pound woman out of her bed.

Going into this, I had no idea Melissa Rosenberg wrote it. But now that I know, a lot of things make sense. Jessica Jones contains plenty of echoes from the ultra-cheesy Twilight series. A female lead. Tortured and frustrated. Meets a man. Wants him but can’t do anything about it. And while the show trumpets itself as dark and cool, I couldn’t help but feel like it was all smoke and mirrors.

Sure, the cinematography is great. Netflix allows for splashier DPs and more takes with their higher budgets. But how edgy is this show? Whenever Jessica Jones has sex, she’s fully clothed. Yeah, because that’s how people have sex in real life. If you want to play with the big boys who really push the limits – shows like Game of Thrones – you can’t be squeamish about that stuff. It’s those moments that break the suspension of disbelief, since now you have viewers wondering about the actor who plays Jessica Jones’ nudity clause and not, you know, the actual scene!

If you want to see a show that truly takes risks and truly has a unique voice (and doesn’t just announce that it does a year ahead of time) go watch Mr. Robot. It’s not for everyone, but one episode and you realize that you’re watching something different. The cinematography alone is so… odd. It creates that unstable viewing experience that Jessica Jones only wishes it could accomplish.

And now that I think about it, I’d argue CBS’s Supergirl is more inventive than this show. At least that show took a chance and went away from the groupthink trend of dark superheroes. Instead, it went the fun route and while I’ve only seen the extended trailer, it looked like a much better time than this.

I guess my final question with this show is: What’s the big deal? Why are we supposed to like this? What does it bring to the table that’s different besides a high production value? Cause all I see is some angsty chick who’s being angsty for no other reason than that it’s cooler that way. If I wanted Veronica Mars with the lights turned off, I would’ve downloaded it on Itunes. I wouldn’t say I hated this show. But I got close.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never write a screenplay or teleplay because you think the show would be “cool.” Write it because you have an idea to explore, characters you want to dig into, a theme you wrestle with daily. The savvy viewer (and almost all the execs out there) can smell something that’s all flash and zero substance. Jessica Jones pretends to have substance, but it’s as thin as the comic book paper it was originally published on.

Genre: Sci-fi Thriller

Premise: A young biologist is recruited on a mission into a mysterious energy field that threatens to destroy the planet.

About: Writer Alex Garland has blessed us with some of the best sci-fi of the last 10 years. He wrote Ex Machina, 28 Days Later, Sunshine, Dredd, and even adapted mega-project, Halo, before the 67 lawyers and producers representing the 13 companies involved in the film blew the thing up. In short, if you have a sci-fi project, Alex Garland is one of the first guys you call. This time, just like he did on Ex Machina, he’s writing AND directing. Annihilation was adapted from the novel of the same name. It is being referred to as the first book in the “Southern Reach” trilogy, which means nothing to me at the moment, but will hopefully make sense at the end of the review. It will star Natalie Portman.

Writer: Alex Garland – Jeff VanderMeer

Details: 126 pages (version “10” according to the title page, whatever that means)

Longtime screenwriter Alex Garland stormed onto the directing scene early this year, writing and directing one of the best indie films of 2015, Ex Machina. How did he parlay his writing into such a deftly directed first film? By, um, not giving a shit about directing apparently! Garland’s gone on record as saying he doesn’t like directing nor does he care about it. To him, it’s all about the writing. Spoken like a true screenwriter.

With that said, you have to wonder why someone who isn’t into directing has agreed to direct another movie so quickly, and a big one at that. My guess is that the salary bump from writer to director is enough to make even the most reluctant writer reevaluate. And hey, spending three months in close-quarters with five beautiful woman doesn’t sound like such a bad gig.

Biologist Lena Kerans, who specializes in cancer research, is struggling through the most difficult time of her life. Her soldier husband went missing in battle over a year ago, and Lena hasn’t been able to move on.

Then, one day, inexplicably, her husband (Kane) returns home. Kane has no memory of how he got here and no memory of where he’s been. When Lena rushes him to the hospital, a government motorcade intercepts them, and the next thing Lena knows, she’s waking up in a military base.

Eventually, she meets Dr. Ventress, who informs Lena that they’re off the coast of Florida where a large growing anomaly is taking over the area. Within a few years, it will extend down into Mexico. Within a decade, it will usurp the entire planet. Great, Lena says. Now where the fuck is my husband?

Ventress explains that her husband is being kept on life support, and with the anomaly approaching, they’ll have to desert the base soon. If that happens, they will have to leave Kane, as he’s in too fragile a state to be transferred.

It just so happens that Ventress is going on one last mission with a group of three woman into the anomaly to see if they can figure it out. We gradually learn that Kane was on one of the former missions inside the anomaly and that he’s one of only two men who made it out alive.

Naturally, since her husband’s life is on the line, Lena demands to be a part of the mission. And she makes a good case for herself. She’s a biologist, and this growing anomaly is basically a cancer. Maybe she can help.

Ventress agrees, and the team of five women head inside. Once in, they notice that everything is both the same yet different. The animals (gators!) are twice as big. The plants are twice as exotic. And time doesn’t seem to exist wherever they’re at. But when they come across video of Kane’s old team, they begin to realize just how dangerous this anomaly is, and that just like everyone else who’s ventured into this bubble, they’re probably not making it out alive.

“Annihilation” asks a pretty interesting question. What if the earth got cancer? What if a mutation started to spread and expand to the point where the earth itself died? That’s a great sci-fi question. But it also teeters on the edge of “3 A.M.” idea territory. You can almost smell the pot wafting through the outline’s pores.

Indeed, I can hear the echoes of someone nicknamed “Lugnuts” ingesting an epic bong hit and wondering aloud, “And what if, like, all the animals were, like, TWICE AS BIG,” to which he receives a smattering of delayed approvals, peppered with the occasional pot-cough-slash-laugh. Surely, a pizza will be ordered soon, charged to whichever member of the group is getting his entire tuition paid for by daddy.

Okay, that may be a cheap shot. But Annihilation does suffer from a case of the over-idea. It’s the price you pay when you go from something contained and clear, like Ex Machina, to something sprawling and ambitious, like this. You gain scope and complexity. But you’re forced to juggle more balls. Which means a better chance of those balls falling.

But I’m not here to judge (okay, maybe a little). I’m here to observe. And one of the first things I observed was the concept of “mystery replacement.” When you write a script like Annihilation, where the first act is centered around a mystery (a growing field that people go into and never come out of), you’ve set yourself up for a front-loaded movie. That is, once you show the audience what’s inside the bubble, they’ve got nothing left to look forward to besides the next bong hit.

Because the entire first act is predicated on the mystery of this unexplainable phenomenon, Annihilation is a prime candidate for front-loaded status. Luckily, there’s a solution to this. Every time you answer a giant mystery in your script, you replace it with either another giant mystery, or a series of smaller mysteries. VanderMeer and Garland do a good job with this. Once we’re inside the phenomenon, new questions start arriving. Giant animals. Grotesquely altered humans. What happened to Lena’s husband’s team?

I also want to commend Garland on the structure, which is one of the first things beginner screenwriters must learn before they can make the move to the more complex aspects of storytelling, like character development and theme. So instead of sending our characters into this big anomaly blob and “seeing what happens,” (a common mistake I see a lot), Garland immediately establishes a goal. Get to the lighthouse. The lighthouse is where the anomaly began, so by that logic, that’s where the answers will be.

This may sound like a minor thing, but it’s actually really important. Having a physical destination gives us form and focus. We know where the story needs to go, so we can give in to all the craziness that happens along the way. Had we shown up here and the characters said, “Uh, okay, let’s look around,” we the reader are going to get frustrated quickly. “What’s the point?” we’re going to ask. “Where is this going??”

An overarching goal is a great start. But sub-goals are what really give a script structure. In Annihilation, the characters know they can’t get to the lighthouse in one day, so they create a series of checkpoints they’ll try to make it to each day. Again, this may seem insignificant to the casual screenwriter. But what this is doing is dividing the screenplay into easy-to-follow bite-sized chunks. We know we’re trying to get to A. Let’s see if we can get there without getting killed. Next morning, we have to get to B. Okay, let’s see if we can do that. Then C, and finally D. And, of course, if you’re doing your job, each leg will be more challenging.

Think of these mini-goals as pillars. If you were to place a pillar under the left side, or beginning, of the screenplay, and then place a pillar under the right side, or ending, of the screenplay. What’s going to happen to the middle? It’s going to sag right? So you have to place a series of pillars along the middle section of the script. That’ll keep it from drooping, or worse, falling down completely.

And if structure were all this script were being judged on, I’d give it a good grade. But I also have to judge it on its ideas, which are interesting in some places but muddled in others. The “What if earth got cancer” question is fun. But I’m not sure I understood why plants and humans and animals were meshing into single forms. And why sometimes that meant weird hybrid entities, and while other times it meant dolphins as big as whales. There was an inconsistency there that became frustrating after awhile.

And something smelled fishy about this team being all-female. The explanation we get is that men could potentially be more violent inside the vortex and therefore less likely to survive. The problem with that explanation is that over 500 people have gone into this thing, and only two have gotten out. They were both men. This tells me the all-female team is more a result of that being the hot new thing in books than it is a logical decision. And hey, if you want to go all-female or all-male or even all-horse, that’s fine. But it’s your job as a writer to come up with a legtimate reason for why that’s happening. If you don’t, the suspension of disbelief is broken (note: Suspension of disbelief is broken every time an audience veers out of the movie to ask a logic question: “Wait a minute? Why are they all women? That doesn’t make sense.”)

It’s the same issue I have with the Ghostbusters thing. What’s the reason to go all-female other than that’s the trend? There isn’t a story reason behind it. And if you’re deliberately excluding men from the story, isn’t that just as bad as deliberately excluding women from a story?

But I’m getting off-track here. Must have been that five minutes I spent watching Trump debate earlier. The main point is that Annihilation starts out with an interesting idea, and keeps its story moving swiftly, but once the answers start coming, they do so in unsatisfying muddled ways. With that said, I’m curious what Garland’s first large-scale directing effort will look like. The cinematography as well as the robot concept in Ex Machina were gorgeous, which is reason to stay optimistic.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One way to look at structure is to come up with 5-6 checkpoints (in this case, destinations) that divide your script into a series of bite-sized chunks. Now you can focus on making each individual chunk great, and not have to stare down into this endless chasm of broken dreams.

Each week myself or one of the site’s readers will suggest an obscure, unknown, or under-appreciated film that you guys can then watch on a Lazy Sunday and discuss the screenwriting merits of. If you’re interested in submitting a suggestion, e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the movie and a 300 word “pitch” on why you think people would enjoy the film. Together, I hope we can all find some hidden gems.

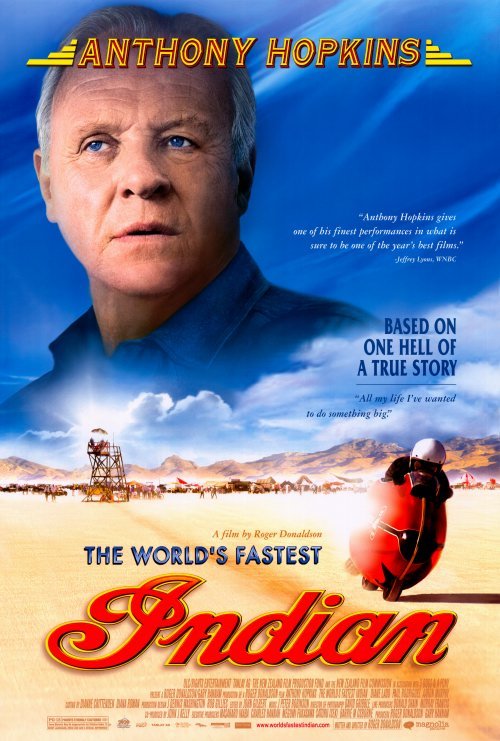

Today’s movie is The World’s Fastest Indian, a film that had the single worst title of any film, maybe ever. You put Anthony Hopkins on a poster next to the title, “The World’s Fastest Indian,” and everybody’s going to think that an old white man is playing an Indian who tries to run the 40 yard dash in the Special Olympics or something.

This movie is not that at all. It’s about an older simpleton from New Zealand who travels to America in the 1950s to try and set the motorcycle land speed record. His motorcycle is called “The Fastest Indian.” This is a movie that is guaranteed to make you feel good afterwards. If you are having a bad day, a bad week? Watch this film and all those yucky feelings will slip away. This has a character who is impossible not to root for. It’s basically a more grounded version of Forrest Gump. Enjoy!

Thanksgiving is coming up next week. And if you’re anything like me, you’ve purchased a stomach expander on Amazon to prepare for the event. I’ll tell you what I’m not prepared for though. Another one of these Hunger Games movies. Which one are we on now? Breaking Flames No. 7 Chapter 19? How is a movie about hunger games still going if it’s no longer about hunger games? It’d be like if you made a Star Wars movie about trade negotiation. If you’re looking for something to watch instead of JLaw, check out Jessica Jones. Not because I recommend it. I haven’t seen it yet. But it’s supposed to be the greatest show on television, so I’ll be discussing it on Tuesday. If you want to join in on the conversation, best get your binge on.

Title: Let the Punishment Fit the Crime

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Logline: Hollywood icon Chad Burroughs is America’s best-loved human being. But the world is about to find out that Mr. Perfect has had his daughter locked in his basement for the last 13 years, and that she is the mother of his children – the ones he hasn’t disposed of.

Why You Should Read: This is my fifth script, and I’ve tried to incorporate everything in it that I have learned from this site over the years: it has GSU, shocking turnarounds, a bitchin’ Bad Guy, a big reversal on page 24, dialog that “pops”, a low character count, a short time-span, dramatic irony, it’s a thriller…

On the other hand, it is based on factual events and does break a few rules.

I would love to know what people, and in particular Carson, think.

Even if you don’t get that far into this script, I would really appreciate it if you could read the turnaround on page 24 and let me know what you thought of it.

Title: Language of the Birds

Genre: Urban Dreamed

Logline: (The Fisher King meets Charles Dickens) A famous bi-polar Linguistics Professor retracts from the modern world and ends up homeless in NYC to live the vicarious life of Charles Dickens. Through the language of birds, he discovers the syntax of living ‘in the moment’ and sets out to build a monumental Christmas tree in Times Square, to reconnect with his daughter.

Why You Should Read: I’ve crashed and burned many times into the pit of Scriptshadow sorrow, but like all of us committed to this dream, we dust off the pride and search for that next big cathartic script. ..Only to find ourselves in another writing frenzy and come out the other side burnt. Well, I haven’t crashed yet! This is an original story from the heart, pitched at those of us that linger in old fashioned literature, in a modern world of language reduced down to 140 character ‘tweets’. It also touches on mental illness and the homeless, especially on Christmas Day; the loneliest day of the year for a lot of people in NYC. Despite all that, it’s a fun and uplifting story of humanity, when we’ve all been guilty of awkwardly side-stepping that homeless person. Those ‘crazies’, that dare to live in the moment, inside their heads…Give them some empathy next time, most are probably failed screenwriters! A little bird told me that I should wait; I might have a better chance with this script in next year’s Scriptshadow 2500 contest. The Grand Prix of Pits… Enjoy.

Title: HEXEN (Witches)

Genre: HORROR/THRILLER

Logline: When a desperate man drags his depressed wife and step-daughter to rural Germany for family support; what he discovers instead are dark cult roots, an isolated hippy haven, and the terrifying realization that they may not be free to leave alive.”

Why You Should Read: My name is Alex Ross, and my screenplay, HEXEN, won the grand prize in the Script Pipeline competition (out of 3,500 scripts) and is also highly rated on the Black List as “top unrepresented horror”. Here’s why I would like the script to be reviewed: I see HEXEN as a fresh take on a very stale and predictable genre. It’s a throwback to the thrillers from the 70’s (Rosemary’s Baby, The Shining, Don’t Look Now), but with a modern, realistic approach. It purposely breaks the tired “rules” of horror storytelling, which audiences have come to expect by now. A main protagonist vanishes half-way through, character’s motives are ambiguous, and the ending is left somewhat open-ended. Say what you will about the script… one thing it’s not, is predictable. However, it has alienated some who are looking for something a little more mainstream, and I’m finding it difficult to find industry pros who can see outside the box, and who are willing to take a chance and get behind it. I need all the help I can get…

Title: Mind Crime

Genre: Thriller

Logline: An unlawfully convicted man serves every day of his 25 year sentence, but when released he finds out only two weeks have passed from his sentencing date.

Why You Should Read: I know this is a bold statement, but I challenge everyone who reads this that you will not be able to guess what is going on until YOU READ until the end. No cheating. Whatever you think it is, when you find out, you’ll even be more shocked. Everyone wants originality, and by the second Act, you’ll be steeped in it. Maybe a little too far. It is truly hard to find a thriller idea that keeps you guessing, but when this one came to MIND, I had to take a stab at it. I have written for some actors such as Ron Perlman, Ving Rhames, and producer Steve Whitney. But so far, I haven’t luck with the Hollywood patience game.

Title: DESTRUCTO

Genre: Black Comedy/Sci-fi

Logline: Struggling financially, a young man retrains as a programmer and discovers that robots are walking among us. When one murders his brother, he sets out to find their origin and their mission.

Why You Should Read: I was disappointed when this one didn’t make the 250. From your columns, I believe my logline didn’t show enough conflict. So I’m trying AOW with a revised logline. And one more thing – robots. Like in your April 23 article, Hollywood’s Subject Matter of Choice. Ring a bell?