I know you’re all wondering about the Scriptshadow 250. I’ve already started e-mailing the top 250. I’m going to be doing that ALL DAY. Since I’m also going to the movies, I may be e-mailing some people deep DEEP into the night. But if you haven’t received an e-mail by midnight Sunday (Pacific Time), it sadly means you didn’t make the cut. Make sure to check your spam and promotions folders just in case. And to help you pass the time so you don’t go insane, here are 5 amateur screenplays to check out. Vote for your favorite in the comments. To make it easier on me, place your vote (My Vote = Script Title) at the top of your comment. Thanks. This should be a fun day!!

Title: By Forces Unseen

Genre: Thriller

Logline: A drifter with a secret past finds friendship and love in Portland’s animal liberation underground, but the longer she stays, the more she puts everyone at risk.

Why you should read: Our relationships with animals are complicated, if not morally schizophrenic – pet this one, eat that one. Is the Animal Liberation Front made up of heroes willing to risk their freedom to save animals, or are they violent terrorists? Or something else? Regardless, I think these people lead interesting double-lives.

Title: Pinchers

Genre: Comedy, Horror, Sci Fi

Logline: The 100th annual Crab Fest is right around the corner and a small town starts to experience a series of grisly murders that could be the work of a serial killer… or giant crabs.

Why you should read: As a fan of Scriptshadow, I wanted to submit something that was a little more “fun”. There’s a lot of great scripts that come through the site, but I feel like there aren’t a lot that fit into that “Tremors” or “Pirahna” mold. I wanted to submit Pinchers because I wanted to submit something that’s meant to be watched on late night cable with beer and pizza. I’m excited to get feedback from a community of writers who may not read these types of scripts that often. After reading your review of “See Something” I thought it would be interesting to get your thoughts on a script like “Pinchers”.

Title: La Guerra! (Spanish for War!)

Genre: Action, Comedy

Logline: A couple, who together runs a powerful drug cartel, files for divorce and ignite a turf war when neither party can reach an agreement as to who gets what share of the massive empire they’ve built.

Why you should read: I’m all about the big idea. The big concept. This script is proof of that. Not too long ago, you had a post asking everyone to talk about the kind of movies that they want to see made. Well, I only write the kind of movies that I want to see. This being one of them. I believe this has the potential to be one of those fun, summer tentpole movies. But is it any good? I’ll let you decide…

Title: Born to Die

Genre: Horror-Thriller

Logline: A career con-man with a terminal illness gets a last chance at survival and redemption when the CIA tap him to help locate an old associate thought to be the source of a zombie pandemic.

Why you should read: As for me, I’m a Chicago-based amateur screenwriter focused on features and pilots and like everybody, looking for representation. I’m also looking to learn and improve as much as I can with each script. “Born to Die,” is a horror crime-thriller in the vein of “28 Days Later” meets “Zero Dark Thirty.” (i.e. Zero Dark Zombie) The zombie genre is well-trodden territory but what my story aims to do is focus on character, spine-tingling thrills, and thoughtful twists to create a unique take on why audiences find these films terrifying and compelling. It blends the horror and crime-thriller genre with the goal of creating an intelligent, thrilling, and terrifying script with a unique voice.

Title: The Only Lemon Tree on Mars

Genre: Science Fiction

Logline: When recent, inter-global events threaten to disrupt the idyllic life on the first Mars Colony, a woman with a secret to hide must do all that she can to prevent neighbors in her small town from taking up arms against each other.

Why you should read: I believe that audiences want to be challenged. Why? Because I go to the movies a lot and I like to be challenged. So, it stands to reason that when writing I choose topics that are challenging with characters who are flawed but relatable. This is what led me to write “The Only Lemon Tree on Mars.” Like all good sci-fi there’s an allegory about today buried in there; specifically the modern political process. And although there are a few action beats, it’s really a drama about a woman struggling to make the world better despite the machinations of men. Most importantly, she does this by being a woman, and not acting like a man. In this day and age, that’s an important distinction.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise (from writer): In a future where robots run grisly human-fighting rings for sport, any human who survives 72 matches is given 72 minutes to win their freedom–or die.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I moved to Los Angeles to specifically pursue a career in waiting tables. I was originally gonna write a biopic about Nikola Tesla’s chef, but figured this would be more interesting. This script has such a big fat concept, that when it took a selfie, Instagram crashed. Do not read it if you hate: space, hyper loops, nihilism, invisible architecture, and futuristic theories. FULL DISCLOSURE: I’m an alien that’s trying to blend in with everyone.

Writer: Robotic Super Cluster

Details: 85 pages

I suppose Game of 72 was the perfect script for today. As I struggle to decide on my last few slots for the Scriptshadow 250, my mind is on the verge of madness. And let me tell you, there isn’t a better script to read when you’re on the cusp of insanity than this one. I want you to imagine Steven Spielberg making A.I., but with Rob Zombie’s brain downloaded into his cerebral cortex. The word “trippy” doesn’t even begin to describe this bizarro eye-assault.

But before I get to that, I want to know which movie I should see and review for Monday. This is the best movie weekend of the year so far, with Sicario (great script), The Martian (great writer success story) and The Walk (amazing special effects) all coming out at the same time! I’m considering doing my first triple-feature in ten years, but I don’t think I’ll have the time. So which one do you want me to review? There’s no wrong answer!

Okay, on to Game of 72, which was my favorite logline of the bunch so I’m glad it won. Well, I should say I WAS glad that it won. Now? I’m not so sure.

The year is 2820. Earth is run by robots, aliens, and genetically modified monsters. The only thing these beings seem to care about is entertainment – specifically human-on-human fighting. They take the humans, chain them up like dogs, torture them, strip them of their names (replacing them with numbers), and force them to fight each other to the death.

Sounds fun, right?

The only way for humans to escape this misery is to win 72 fights (nearly impossible), after which they’re entered into something called “The Game.” In “The Game,” you have 72 minutes to catch a wandering orb. If you succeed, you gain your freedom, are upgraded into a human-robot hybrid, and get the choice to live forever.

So the stakes are high.

Our hero, 28 year old Finn, is one of the few fighters who’s managed to accumulate 72 wins. He joins two others who have managed this impossible feat – Nala and #9560 – and before the trio even knows what’s going on, they’re thrown onto an interplanetary train that shoots them off to Mars.

When they get to Mars, none of the monsters or aliens have ever heard of The Game. They don’t even know who these humans are. In fact, there’s no one to tell them how this game works. Complicating matters is that there’s a disembodied voice living inside of Finn who keeps telling him to do the opposite of what everyone tells him to do.

No more than five pages after we arrive on Mars, our players are told they’re going back to Earth, so they jump on another flight, and arrive into some kind of mind disco. Yes, a “mind disco.” As it’s explained to us, the music isn’t actually being played. It’s “transmitted through everyone’s bodies and souls, emanating from within.” Huh?

I could go on here, but I think you get the gist: THIS SCRIPT IS FUCKING NUTS.

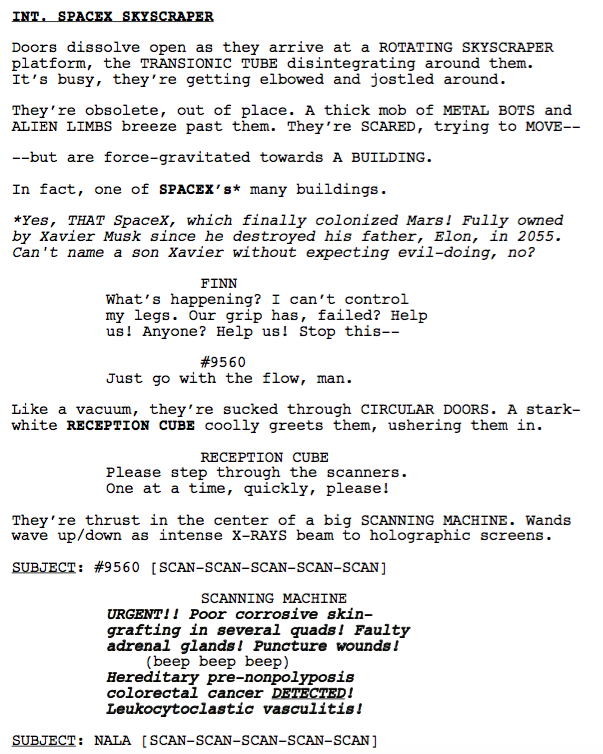

Look, I’m all for imagination. Just yesterday I was complaining about writers who DIDN’T use imagination when writing their queries. But there’s adding jam to your sandwich and there’s dumping the entire jar on it. Game of 72 throws you into an information ocean, never letting you above water to catch your breath. Here’s a typical page from the script:

Let’s see what we’ve got here:

1) Italics-based writing.

2) Bolded writing.

3) Underlined writing.

4) TONS of information.

5) TONS of imagery.

6) Manic writing style.

7) Characters with number names.

The whole script reads like this. Here’s another line, picked at random: “He FALLS, an accordion of 100-copies of him are frozen mid- AIR. Thousands of MAGNOID thoughts enter his head. DEAFENING. The sensation of sinking into LAUGHING GAS, nitrous oxide.”

Huh?

I’m not even sure what to say. I mean, our writer is clearly talented. He had one of the best “Why You Should Reads” of the year. It showed that he’s clever, he’s imaginative, he can write. But it feels like for this script, he ingested an entire Starbucks store and wrote everything freehand, gripping the pencil like a knife, and stabbing 20,000 words onto the page without ever going back to see if he’d murdered anyone. Particularly the English language.

This is a cut and dry case of information overload. Too much style, too much imagination, too much action, too much information. As screenwriters, we do want our scenes packed with action and plot. But there’s a difference between drinking a beer and buying the brewery.

Truth be told there were a couple of red flags before my exhaustion kicked in. People use bitcoin in the year 2820? Space-X (created by Elon Musk) is the main form of transportation? I might buy into this if the year were 2075. The year, however is TWENTY-EIGHT HUNDRED! There wouldn’t be any recognizable brands still around, especially if the world had been taken over by robots and aliens.

The official moment I gave up on the story was when we went to Mars, and after five pages, came right back to Earth. To me, that indecision embodied the script’s biggest issue – its lack of focus. Our writer couldn’t find something interesting to do on an ENTIRELY SEPARATE PLANET, to the point where he had to bring our characters right back to the place they left just minutes ago.

And if you took the time to look deeper, it didn’t seem like anything had been thought out. Why didn’t anyone on Mars know about The Game? And if nobody knows about The Game, then aren’t you telling the reader that it’s not a big deal? And if it’s not a big deal, why should we care if these characters succeed or not?

In the flawed but fun Arnold Swarzenneger movie, The Running Man, the whole world watched that show. The writers made sure you knew everyone on the planet was obsessed with it. So the objective seemed important. With these characters, they’re not even sure if they want the prize (to live forever). Protagonists who aren’t even excited about achieving their goal? That’s a recipe for screenwriting disaster.

I like this writer here. I just think he tried to be too cute and stuff too much into every page. Dial the imagery back. Dial the world-building back. Get rid of the unnecessary details (the 9th version of the monster subset).

I say this over and over and over again, and nobody listens. The best screenplays are simple easy-to-understand stories with complex characters. Once you switch that emphasis around (to a complex story with simple characters), I won’t say you’ve hung yourself, but you’ve definitely tightened the noose.

This script was such an assault on my senses that I almost gave it a “What the hell did I just read?” Seriously, it got to the point where it hurt my head to keep reading. You’re a talented writer and better than this. Let’s nail the next one.

Script link: Game of 72

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Information overload is a script-killer. Nobody wants to be inundated with description-porn on every single page. Dial it back. If it’s not easy to ingest what’s on the page, we’re going to give up on you fairly quickly.

As we near Saturday, when I’ll contact all 250 writers who made it to the next round of my contest, I find myself emotionally exhausted. I’ve read so many stories from writers who have given up everything for this craft. Some have moved from other countries. Some have health problems so severe, they can’t leave their beds. Some are weeks from being kicked out of their apartments. A few are even homeless.

I wish I could make every one of those writers’ dreams come true. But the reality is, I’m not letting screenplays into this contest out of pity. If you didn’t bring your S-game (Script Game), your script didn’t get chosen. And as harsh as that sounds, it’s the way the industry works. If you can’t tell a good story – even in e-mail form – you’re not ready yet.

So today is about highlighting the mistakes I saw in your queries in the hopes that you never make those mistakes again. If there’s a theme to my observations, it’s this: Be professional. If there’s even a hint of sloppiness or laziness in your query, no one’s going to take you seriously. Keeping that in mind, let’s look at the ten biggest mistakes queryers made.

1) Generalities kill loglines – There were a lot of loglines where the writer didn’t give me any actual information. They wrote in vague generalities that didn’t convey what the script was about. Something like, “A mother who questions her life must combat a powerful force that threatens her very existence.” Honestly, it seemed like some of you were actively trying to say nothing. The whole point of a logline is to show what’s UNIQUE about your idea. To achieve that, you must be specific. “When a mother’s developmentally challenged son conjures up a haunting monster known as “The Babadook” from one of his books, she must battle her own sanity in order to defeat it.” That’s what I mean by specific.

2) Word-vomiting kills queries – Beware the writer who takes twenty words to say what they could’ve said in five. These writers add qualifiers and adverbs and adjectives and empty phrases to every sentence they write, making the simplest points exhausting to slog through. For example, instead of writing: “My movie is about a boxer who gets a shot at the heavyweight championship of the world,” they write: “I have a story about a boxer, the kind of man who’s kind, yet forceful when the moment requires it, embracing the challenge of a world that seems to be, but never overtly tries to be, his worst nightmare, and the way that man, my main character, struggles to achieve and eventually is able to secure, a chance to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world, in Philadelphia, the city of brotherly love.” STRIP. YOUR. QUERIES. OF. UNCESSARY. WORDS. PLEASE. GOD.

3) Lack of conflict in a logline is a deal-breaker – You need to convey what the main conflict in your story is. Conflict is story! It’s the problem your main character must overcome to get to the finish line. I read a lot of loglines like this: “A young man experiences a spiritual awakening when he switches from being a Christian to a Muslim.” AND???? What is the conflict that tries to impede upon this switch? Lack of conflict in a logline means the writer doesn’t know what conflict is. If that’s the case, their screenplay is guaranteed to be boring. I mean 100% of the time guaranteed. Guys, if you don’t know what conflict is, go spend the weekend googling it.

4) The words/acronyms “CIA,” “agent,” and “FBI” combined with “terrorist threat” do not, on their own, make a movie – I must’ve read 50 loglines that were some variation of, “A CIA agent goes undercover to tackle a terrorist threat in London.” Secret agents and terrorist threats are some of the most potent plot elements in the movie universe. But they’re worthless on their own. They need a unique element to team up with.

5) Trending subject matter will always have an advantage in the query department – The trend of the moment is biopics. They’re the only thing that’s selling. So I admit that when I came across a biopic, as long as the query was competently written, it got in. Remember that everybody involved in the movie-making chain is trying to sell the project to the next guy up the ladder. I know Grey Matter will have to sell the winning script to the studio at some point. And the studio is more likely to buy a genre that’s doing well at the moment.

6) Focused loglines were always the best entires – One of the easiest ways to identify strong contenders was a focused logline. Unfortunately, the far more common logline was one that started in one place and ended someplace completely different. So I’d get something like this: “A down-on-his-luck mobster trying to open his own casino joins a cooking class and falls in love with his teacher.” Whaaaattttt??? How did we go from casinos to cooking class??? I saw this a LOT and the scary thing is, the writers who made this mistake are probably reading this right now and have no idea they’re guilty of it. That’s because everything connects logically in your own head. It’s only through objectivity that we see disjointedness. Take a step back and make sure you have a FOCUSED movie idea whose beginning, middle, and end, all tie together.

7) The overly mechanical query is digital Ambien – I read a lot of queries where writers were logical and succinct and measured in their pitch… and that fucking bored me to pieces. What these writers were saying was fine. It was HOW they were saying it that was the problem. There was no life to their words, no fun, no spontaneity. I’d read stuff like: “My goal was to eliminate the passive protagonist that’s been an Achilles heel to this sub-genre and replace him with a character that embodies the ideals of the thematic construct of revenge. In doing so, I’ve achieved an energy that was missing in my earlier drafts, but which I could never pinpoint. The resulting script is one that utilizes four out of five of the story engines that drive the classic “man vs. nature” tale…” AHHHHH! KILL ME NOW!!! Writing is supposed to be FUN TO READ. Even when you’re making a serious point, there should be a relaxed easy-to-digest demeanor to your writing. This style of query 100% OF THE TIME means the script will have no voice. So these queries were the easiest to reject.

8) Beware the logline that is at war with itself – I read a lot of loglines that felt like civil wars, with words jockeying for position as opposed to working together harmoniously. These writers had the “stuff it in there” mentality that should be reserved for the condiment section at a hot dog stand, not an e-mail query. Here’s an example: “A cowardly gunfighter is at odds with his idealism and the secrets he’s kept when a rival gunsmith rides into town, looking to settle a score that will help forge the frontier line between New Mexico and California.” A logline isn’t a contest to see how many words you can include. It’s a vessel to get your idea across as simply as possible. It should flow. If it doesn’t flow, rewrite it.

9) Don’t use weird adjectives to describe your main character – Every tenth logline I’d read, I’d get something like this: “A pestered train conductor plans a heist…” “Pestered???” The character adjective should give us both the defining quality of your hero, as well as CONNECT your hero to the plot of the movie. So let’s say your script is about a train conductor who decides to rob his own train. The adjective might be: “An exemplary conductor is forced by his wife to rob his own train after losing his family’s life savings.” I don’t love this logline but at least the adjective connects with the plot. This is a conductor who’s built his career on trust. He’s the last one you’d think would rob his own train.

10) Avoid the cliché opening-page overly-poetic description – Whenever I was on the fence about a query, I’d pop open the script and read the first few lines. If the overly poetic description opener made an appearance, it was bye-bye scripty. What is the “overly poetic description opener?” It’s when a writer who’s clearly uncomfortable with poetic descriptions starts their script with an overly clunky poetic description: “The sun-dappered late-afternoon light plays tic-tac-toe with the suburban rooftops.” No. Just no. Look, if describing an image in a poetic manner isn’t your forte, start with something else – an action, a mystery, your main character speaking. But if you dapper any suburban rooftops, goddammit I’m shutting you down, son.

If I could give writers one piece of advice when it comes to querying, it’d be the same advice I’d give them in regards to screenwriting: FOCUS. Get to the point. Convey your idea clearly. And being entertaining doesn’t hurt. It’s important to remember that you’re trying to convince a person to read something of yours BY READING SOMETHING OF YOURS. So if the short version of your writing isn’t enjoyable, there’s no way they’re going for the long version. Make your query focused and enjoyable to read, and there’s a good chance that reader will give you a shot.

Genre: Biopic/Action/Period

Premise: A young George Washington fights to gain the respect of the British Army during the French-Indian War.

About: This is a juicy mid-six figure sale from a couple of weeks ago. The script is from Aaron Sorkin protégé Michael Russell Gunn, the son of a Christmas tree farmer (hey, what’s more American than that!). Gunn’s written on The Newsroom and Black Sails, but this is his first feature effort. New Line, the buyer, will now race to get the movie made before a competing project from Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese. There have been some rumblings (mostly from the internet PC police) that a movie about Washington should not be made, since he owned slaves.

Writer: Michael Russell Gunn

Details: 115 pages – undated (but I believe this is the draft that went out a couple of weeks ago)

When you think about the explosive biopic trend, you wonder why a George Washington spec hasn’t hit the town sooner. I mean we’re talking about the most famous man in American history. Even 9th graders at Hollywood High who couldn’t name our vice president without the help of Siri, recognize Washington’s name (albeit because his picture gets them an order of fries at the nearby In and Out, but still).

So why haven’t we gotten a big George Washington biopic before? I think because the guy’s boring, right? He never lies. And movies are about lying. Think about it. Every movie is based on some form of lie, deception, or the withholding of information. So if a guy can’t pull a cherry tree hit-and-run without feeling guilty, where are you going to go with the character? To that end, it doesn’t matter how popular you are. If you’re boring, people don’t want to watch you. Well, unless you’re Kim Kardashian of course.

As if sensing our collective skepticism, Gunn throws us into the story with Washington mercileslly beating down two Indians to save one of his soldiers. We immediately realize this isn’t our grandma’s George Washington. Or our grandma’s grandma’s grandma’s grandma’s grandma’s grandma’s grandma’s grandma’s George Washington. No, this is George Washington by way of 1989 Arnold Swarzenegger.

Not to get too “history” on you, but the story is set during the French-Indian War, when Britain was still occupying the U.S., and fighting France for control of this bountiful new world. Washington was one of the few locals to rise through the ranks on his merit (and not his family name) alone to become captain.

But after losing a town to the pesky French (French were still pesky even back then), he’s stripped of his captain rank and told he doesn’t have the goods to lead an army. Pissed off, Washington accepts a job surveying land for a local divorcee, Martha, whose farmland is drying up due to her neighbor controlling a nearby river. A master surveyor (this is how Washington made his name), she wants him to find a way to save the land, and along with it, her estate.

Unfortunately, Washington is pulled away by the British, who need his land-surveying prowess to take a key Frech city up north that, according to them, will determine who wins the war. Limited to consulting duties, Washington is itching to get back into action. But the British don’t believe he can lead an army. Will Washington be able to prove them wrong?

First off, I want to commend Gunn for selling this script. Part of getting that elusive script sale is strategizing (not unlike Washington) what Hollywood is looking for and how your particular writing strengths can give it to them. Too many writers write whatever comes to mind, never doing any research into whether Hollywood would actually want the material.

Coming off of Lincoln’s success, it was clear that audiences were willing to pay up for stories of historic American heroes, and so Gunn pounced on a Washington biopic.

I also loved the opening of The Virginian. Remember, you always want to use the reader’s expectations against them. George Washington is synonomous with the stately proper figure on the face of the one-dollar bill. So what’s the opening scene? Washington recklessly ripping two Indian soldiers to shreds. Boom, everything we thought we knew about Washington is turned on its head.

But that’s not all. As soon as Washington saves his soldier from these crazed warriors, he reaches down to pull him up, only to have the soldier CLOCK him upside the head and RUN. Wait a minute – WHAT??? Our hero just beat down two Indians and saved this man from getting scalped alive and he hits Washington and runs???

What we find out is that American militia are deserting their army in droves. They don’t want to die for a stupid war.

This is when I know I’m getting a good writer. Someone who not only establishes their hero in the first scene, but who uses the SAME SCENE to establish an important plot point. Any time writers are doing 2-3 things at once in a scene, it’s a good sign.

However, that’s where my praise of The Virginian ends. The rest of the script wasn’t bad. But after that opening, I was expecting more. When Washington gets the call to use his mapping skills to help the British in a battle up north, I assumed it was a minor battle that would lead to a major battle that’d be the climax of the story.

But no, this was the only battle. And the longer we stayed in it, fighting the same enemy over and over again, our main character relegated (mainly) to staying back and giving advice on terrain, the more bored I got.

The strangest thing about the script, though, was the emphasis placed on Washington and Martha’s letter-exchange courtship, which was oddly built around a remote land survey subplot. It did give us a break from the monotony of the battle, but there aren’t many love stories built around long-distance letter-based relationships that work (maybe in novels, but not in film).

And that brings us to our first big tip of the day. If a storyline doesn’t work, drop it. Because here’s the thing. I get that you want to show how George Washington met his wife. If I’m starting a screenplay about George Washington’s life, that’s something I’d want to include. However, what you plan to do and what becomes feasible to do once you’re in the throes of your story are two different things. You can be stubborn and force something in there that never quite works because that was your original plan, or you can ditch what’s not working and replace it with something more dramatically compelling.

As for Washington himself, I loved the “Washington with Attitude” approach. It energized him in the same way JJ Abrams energized the Spock character in the new Star Trek movies. But that was offset by the heavy attention paid to Washington’s map-making prowess. I don’t care how good of a writer you are. It’s impossible to make map-making cool. And there was a LOT of map-making here. Like, Rand-McNally should sponsor this movie there’s so much map-making.

I think Gunn got The Virginian half-right. Making Washington a tough quick-tempered brawler desperate for respect from the British Army was great. But the film’s main battle felt small for some reason (even though thy told us it was big). The repetition of the fighting was frustrating. And the fact that your main character was barely in those battles was the biggest faux-pas of them all. With that said, it was still way better than the Lincoln script, and I hear that movie did all right.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a wonderful tip for writers stuck in this situation. If your subject matter is perceived as boring (so, for example, you’re writing a movie about an opera singer), start with a scene that goes directly against that perception (so start with the opera singer snorting coke or getting in an alley fight). This approach jolts the reader and assures them they’re getting something completely different from what they thought. If The Virginian started out with Washington giving a four-page courtroom speech about taxes, I can guarantee you this script wouldn’t have sold.

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise: In this “The Burbs” meets “Horrible Bosses” meets “Homeland” mash-up, three middle-aged men suspect their new neighbor of being a terrorist.

About: We’re looking at a sure-fire 2015 Black List entry here. Jeff Lock made his first Black List last year with his meaty absurdist comedy, Beef. Since then he’s obviously been busy. “See Something” hit the town in July with a lot of buzz. And while that buzz hasn’t panned into a sale yet, you get the feeling that has more to do with its box office jinxed genre (black comedy) than the quality of the script. If it does well on this year’s Black List, a sale should follow quickly.

Writer: Jeff Lock

Details: 113 pages – July 13th, 2015 draft

Not that there’s any “best” way to break in as a screenwriter, but if you’re looking for that ideal track, it’s my opinion you want to sneak on the scene with a good but not great script. Sure, it’s bubalicious to get that half-a-million dollar check your first time out. But if you do that, the pressure’s on to deliver on your next script. And if you fail, the industry goes colder on you than Lake Michigan in February.

Jeff Lock did it right. He came on the scene with Beef, a solid but not spectacular script that landed him on the Black List. This allowed See Something to hit the town with a lot of fanfare but no ridiculous expectations. It’s sort of like starting your acting career on one of those good but not phenomenon shows. That’s where you find your Johnny Depps and your Jared Letos.

I liked Lock’s first script, Beef, and mentally tabbed him as a voice to watch out for. What surprised me about his follow-up effort was just how mainstream it was. And I mean that in a good way. See Something definitely embraces a non-PC sensibility, but in the end this exists in the same universe as Horrible Bosses. And that’s not a bad place to be.

30-something Ryan Appleby has just made the transition from working in an office to working at home. He’s not sure how to approach this newfound freedom, and his wife and kid aren’t helping, repeatedly asking him what it is exactly that he does.

To battle the boredom, Ryan hangs out with his two best suburban buddies, Clay and Adam. Adam is one of those fake progressive types who thought buying an African baby would enrich his life, and Clay is that socially unaware hick who thinks that any place that isn’t America is Mexico.

Well, Clay’s about to learn that the new neighbor isn’t Mexican. Pakistani couple Sam and Yasmina look like your typical middle class Americans. But Clay is convinced that because they’re Muslim, they must be terrorists.

When Sam gets a suspicious package delivered to his home, Ryan is curious enough that he joins the trio’s impromptu “Is Sam a member of ISIS?” neighborhood watch campaign. The three begin their investigation by breaking into Sam’s home, move to tracking his car, and eventually come to the conclusion that he’s planning to assassinate American icon, Joe Montana.

While the evidence for terrorist involvement is mounting, the group must weigh the price of freedom against the right to privacy, and that’s something Ryan is never completely comfortable with. Then again, if they can prevent a terrorist attack, isn’t all this moral compass hogwash justified?

See Something had me DYING in the first act. Through the first 30 pages, I was ready to anoint this the best comedy screenplay of 2014 AND 2015. Clay is absolutely hilarious as the dadbod version of Donald Trump: “I know you socialist pansies won’t understand this, but this is America. Other heathen countries in the world are poor, dysfunctional, and living in a big pile of their own shit. (quickly to Adam’s black son) No offense, Abel. (back to guys) They see how awesome America is and they hate us. But, being this awesome comes with a price. You have to watch for all the haters trying to tear you down to get to the top. So we gotta look out for the #1 Emcee in the game… Uncle Sam.”

Even the straight man, Ryan, comes up with some great zingers. His response to Clay’s rant: “You are like some sort of Drake-Rush Limbaugh hybrid.” I’d say I laughed out loud 25 times in the first 30 pages. That is a HUGE number. On the average professional comedy script I read, I might laugh 5 times total. And on the average amateur comedy script, I might laugh once (I’ll be honest, more than often I don’t laugh at all).

But I’ll tell you where See Something (a reference to the government’s message of “If you SEE SOMETHING, make sure to tell the authorities.”) began to lose me. A comedy only works when the plot is working. If the plot is naturally suspenseful and the characters are active and the stakes are high, I laugh at the jokes. Because it all feels real and reality is where the best comedy lies.

But 50 pages in, our guys let Sam know that they think he’s a terrorist. This ripped away the best part of the script, that our trio must sneak around to investigate our potential terrorist without him catching on. Because once he’s onto them, they’re no longer preventing anything. If Sam WERE a terrorist, he now has the option to cancel the mission. Doesn’t this effectively end the story?

The best scene in the script is in that first act when our guys sneak into Sam’s house to look for evidence when he’s out shopping. Why is this a great scene? Because there’s the threat that Sam could come home at any moment and catch them. Once you eliminate the fear of being caught, you eliminate all the conflict and suspense driving the story.

Lock replaces this with a mystery ticking time bomb – the group finds a calendar in Sam’s house with an upcoming date circled. While the looming date does create suspense, it never reaches the previous level of suspense where we were freaked out that Sam might figure out what our guys were up to.

So while the jokes were still sharp, they never hit as hard as they did when I was invested in the story. This is something that comedy writers never consider. If the structure and plot and story aren’t firing on all cylinders, the jokes don’t matter. Jokes only hit when the reader’s invested.

With that said, it’s an easy fix if the producers want to fix it. And I definitely think this should get made. It’s one of the few comedy premises that feels different from all the derivative garbage that’s been hitting the market lately. And I could see top talent dying to play these roles, especially Clay. I guess we’ll have to wait and see what happens!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware the THIRD LAME FRIEND. One thing I’ve found with these “three friend” comedies is that the writer always neglects the third friend. The reason for this is obvious. The first two friends write themselves. There’s always the over-the-top guy and there’s always the straight guy (Phil and Alan in The Hangover). The third friend is the only one in the group whose identity isn’t clearly laid out, so writers are never sure what to do with him.

To fix this problem, I advocate the “label” approach. Label your three friends. So here, Clay is the over-the-top racist. Ryan is the sensible grounded one. Now do the same for the third character. The Hangover is one of the rare comedies that did this well (Stu was the easily-freaked-out pushover). Once you’ve labeled your character, you can focus on demonstrating their identity on the page. But if you never label them and instead write the character on “feel,” I guarantee the character will feel mushy. Adam wasn’t the worst version of this problem. The Ned Flanders label helped a bit. But there was something mushy about his identity that never allowed him to hit as hard as Ryan or Clay. A clearer label at the outset would’ve helped.