Okay so we’re going to try something different this week. Now usually, I filter the submissions and give you only the ones that I feel are good enough to handle the intense scrutiny of Scriptshadow Nation. Even when I do this, I still read replies like, “These are the best options?? Really??” In order for you to make a more accurate assessment of this process, I’m including five COMPLETELY RANDOM SUBMISSIONS. I literally closed my eyes and pointed to the screen. Whatever I was pointing to when I opened my eyes, that entry was included in this week’s Amateur Offerings. That’s not to say one of these can’t be great. But I just wanted to include a “Random Week” to give you a better feel for the average submission. Enjoy!

Title: Guilt

Genre: Drama (100 pgs)

Logline: After witnessing a murder, a crack-smoking, loser lawyer tries to redeem himself by vindicating the teen prostitute wrongly accused of the crime.

Why You Should Read: I cannot imagine a more vital time this story needs to be told. With all that’s been happening in the news over the past year— the shooting of unarmed suspects, and stories of inherent racism and corruption in our justice system— this script is about as relevant as they come.

Title: TENT CITY

Genre: Drama/Gangster

Logline: Arizona. Tent City. Joe Arpaio. 2013. Bunkmates at the infamous outdoor jail start a successful prescription pill drug ring while on work furlough.

Why You Should Read: Along with getting an inside look on the prescription pill epidemic plaguing America, you witness the development of a truly remarkable bond between a black man and white man that they haven’t seen since Brian’s Song. You will never root harder for two drug dealers and will absolutely cringe at the impending doom closing in at the end. — Joe Arpaio is the most hated Sheriff in Hollywood. TENT CITY quietly makes a mockery out of Arpaio and addresses issues such as overcrowded jails, illegal immigration, human rights violation and income inequalities. I carefully crafted this story for liberal producers. — It’s a man’s movie at the core; love triangles, graphic violence, sex, ASU college girls, gangs, drugs and a bromance between two alpha males.

Title: Pregnant Pals

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Two brothers-in-law who hate each other must get along when their wives become pregnant and the couples are forced to move in together to save money before the babies arrive.

Why You Should Read: Having this kid is expensive. More than I even calculated for. And believe me, I calculated. I wonder if there is a simple solution to cut costs and release the worry and anxiety I feel about making all this work. My wife suggested moving in with her sister and her husband during the pregnancy. Smart. But I don’t care for that guy. Can’t stand going to dinner with him. Living with him for nine months? Nah. But my wife. My wife is persistent and she makes a good case. What if we all moved in? What if…

Title: The Ghost

Genre: Action / Thriller

Logline: After being left for dead, one of the most feared assassins must overcome brutal odds,

to bring down the head of the Japanese Yakuza known as, The Barbarian.

Why You Should Read: My name is Gavin from England. I’ve been a big fan of your reviews for a long time. I currently have two scripts under option, one of them being with Bafta winner Noel Clarke. I know you are extremely busy, and I wouldn’t want to waste your time, so I’ve worked on different scripts, but I’ve only just felt ready to send you my work. I currently work two jobs that keeps me busy 11 hours a day, and then I write for 3 hours a day after my shifts, so hopefully you will see that I’m dedicated to the cause my friend, and I’d love for you to review my work (as would most writers).

Title: Clownskill

Genre: Horror/Dark Comedy

Logline: An uptight USDA inspector and her new recruit investigate mad cow disease in a town where clown school alumni with a beef plot grisly revenge.

Why You Should Read: Nothing goes along with grief like beer, banana nut muffins and a really dark, funny screenplay. Something grimly hilarious that lays it all out there – fear and dread and sadness – in ways that your therapist and loved ones would strongly disapprove of or possibly have you committed for. Sometimes you gotta laugh before you can cry. — I was already working on an entirely different script – romantic, grand, tragic, lovely – when life turned a corner and got real. It stayed that way for quite a while. Finally, there was a funeral and a heavy New Orleans goodbye lunch. I drove home, consumed the aforementioned beer and muffin, told “tragic and lovely” I would come back for it later and got to work conferring with a few demons. They were alarmingly eager to oblige. — I really shocked myself that I could think up so many awful ways to kill people. I guess the repressive Southern upbringing has finally paid off. This beast is so far out of my wheelhouse/comfort zone that, honestly, I don’t even know what to make of it. If it weren’t for the funny parts, I probably would lock it away in the attic with my crazy, semi-dangerous aunt. — If the script does make it to Amateur Friday, I can’t wait to get feedback. I took some risks (personally and craft-wise) that may or may not pay off. At the least I hope it entertains a few of you and at best I hope it doesn’t give any potentially homicidal clowns food for thought. Thanks for the consideration and potential reads! And good luck to everyone in the ScriptShadow250!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Thriller/Lifetime (Made-For-TV)

Premise (from writer): When her homecoming ends in tragedy, a desperate single mother spins a web of lies to protect the family nursery from a ruthless property developer.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Breaking into the industry through Lifetime MoW (Movie of the Week) means is legit. Many writers have started out there and transitioned into feature films. It’s a subject we’ve never covered on Scriptshadow in my 4 years there. We’re always focused on high concept studio-oriented stuff. Why not made-for-TV? That career path would make for an interesting discussion in your blog.

Writer: Brett Martin (Electric Dreamer)

Details: 105 pages (note: This is an updated draft from the one posted on Amateur Offerings) – Edit: I’ve been informed that I read the OLD draft. Take that into consideration when reading the review. Sorry about that, Brett!

Long-time commenter and awesome community member, Electric Dreamer, has bestowed upon the Scriptshadow community a challenge heretofore unknown to the reader faithful. To review a made-for-TV screenplay.

We talk about genre scripts and Oscar hopefuls and giant spec sales all the time, ignoring the fact that there’s a huge industry that exists below the line where writers make a living on, let’s just be honest here, guilty pleasure TV flicks. “The Day Janie Left” doesn’t just write itself, you know.

So I thought today’s review could double as primer for the made-for-TV world. If you want to play in the sandbox where the sand isn’t as deep, where you can develop your skills before moving up to the big leagues, then Made-For-TV might be for you. Let’s check out Electric’s “Reap What You Sow” to see what these films are all about.

30-something Gemma has just arrived back in her home town with her 15 year old cancer-stricken daughter, Rose. The two are flat broke and from the bits and pieces of their conversation we’re privy to, it sounds like Gemma is hoping to reconnect with her father, possibly even stay with him, a difficult decision since he’s always been an abusive alcoholic.

But when Gemma shows up at her childhood home, her father is dead, his neck pierced with a broken whiskey bottle. It would appear that he had a drunken accident.

OR DID HE???

When studly Sheriff and former Gemma boyfriend Carl Baxter comes to take a look at the mess, he’s not convinced that this was an accident. In fact, he’s suspicious of the fresh bruises that have appeared around Gemma’s neck.

COULD GEMMA HAVE MURDERED HER FATHER???

While Carl turns the dad’s death into an official murder investigation, Gemma learns that the richest man in town, Walt Sharpe, was just about to close a deal to buy Gemma’s house. It doesn’t take Gemma long to realize that Sharpe wants to build some giant resort, and that her father’s house is right in the middle of it.

Apparently, when the dad died, the contract disappeared. So Walt employs his right hand man, Butch Garner, to form a relationship with Gemma, allowing him access to the house where he might possibly locate this missing contract.

But then Butch starts to actually like Gemma, and everything gets redonkulous. This forces the increasingly psychotic Walt to try and get the house through other means. And through that pursuit, we learn the shocking truth behind who killed Gemma’s father.

Okay, I’m going to start off with some advice right out of the gate. Brett sent me a new version of his script, in which he says he completely rewrote the first 12 pages. I COULD TELL. And this is why I warn writers away from doing massive changes at the last second.

Screenplays are odd beasts. They don’t operate under the known laws of physics. You can look at a change you just made and think, “Wow, I really nailed that. That’s so much better than what I had before.” Then you pick up your script a week later, read the same scene, and it’s like a mentally challenged fifth grader hijacked your script.

What happened?

What happened was TIME. Time allows perspective. When you rush, you don’t have perspective. You can’t see how the changes fit into the larger picture yet.

That’s clearly what happened here because once the script got going, it was fine. It was only the first few scenes that had me confused. For example, here’s the first half-page.

So we’re at a motel. Then we’re told of furniture and a mattress outside and that “It’s Moving Day for someone…” Is this an off-the-cuff description to add color to the writing? Or is this referring to specific character(s) we’re about to meet?

This early in a script, before you’ve identified the style or voice of the writer, you have to assume that everything is being written with a purpose. Therefore, I’ll assume the “moving” has to do with our characters (Gemma and Rose). But if it’s “moving day,” why aren’t they moving from their home? Why are we at a motel?

Maybe they’re in the process of moving? Like they’re on one leg of the journey? Except in the scenes that follow, there’s no actual moving that occurs. The point is, I’m stuck trying to figure something out that should be obvious. And I believe this mistake was made because of rushed writing.

I point this out in my book as one of my tips. Don’t make a lot of changes right before you send your script out. Something’s bound to get screwed up.

Moving on. Reap What You Sow is a very tight story. One thing I’ve realized about the Lifetime/Hallmark movies is that because they embrace formula so openly, they’re perfect for the GSU (Goal, Stakes, Urgency) approach. These movies DESPERATELY want you to use this formula. And they don’t care if it’s transparent.

So here Gemma has a goal – she has to get her late father’s garden/landscaping business up and running to secure the house. The stakes are if she fails, she loses the house. And the urgency is that she only has a month to do it or else Walt gets the home.

But Brett didn’t stop there. Brett use something I like to call GSU-squared (or even GSU-cubed). This is when you give GSU to EVERY SINGLE MAJOR CHARACTER IN YOUR SCRIPT.

So we know Gemma’s GSU plight. But we also have Walt’s. His goal is to get the house from Gemma. The stakes are that if he fails, he can’t build his super-resort. And the urgency is the same time frame that Gemma’s got (since they’re working off the same ticking time bomb – one month).

Then you have Butch. Butch’s goal is to find the contract. The stakes are his standing in Walt’s company. And the urgency is the same (1 month).

By giving every character GSU, your script is always MOVING. Whenever we cut to a character, they have something they’re trying to achieve. And because of “S” (stakes), that something is always important.

If you’ve ever found yourself cutting to characters and they feel boring or static, chances are it’s because they don’t have a goal, or there are no stakes attached to their goal, or there’s no time constraint involved in their journey. Give a character GSU and they instantly come alive.

So Brett did a really good job there.

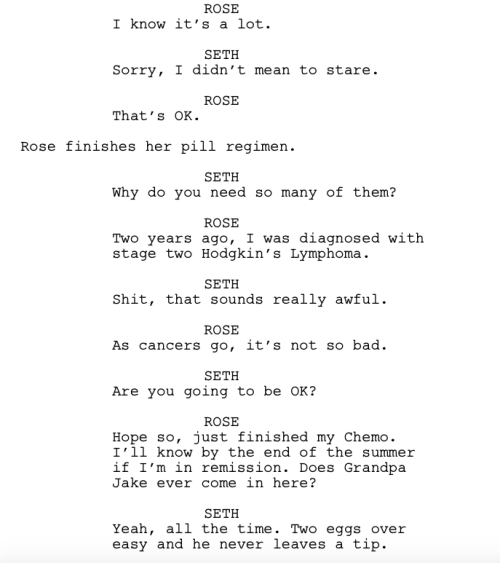

But where Reap What You Sow runs into problems is in its dialogue. And maybe this is because I don’t understand the expectations for dialogue in made-for-TV movies (the extent of my made-for-TV watching is limited to Mommy Dearest), but whether their expectations are low or not, there wasn’t enough LIFE in these words. Here’s a sampling from a scene in which Rose’s new crush, Seth, stares at her oxygen get-up.

It felt like dialogue. It never felt like people talking. And I think that’s because Brett didn’t know his characters well enough. Rose, in particular, seemed like she was only there to add financial strife to Gemma’s situation. I never saw her as a real person. And when you don’t get to know your characters, you don’t learn their little idiosyncrices, their fears and reservations – the things that inform how a person speaks.

For example, I read a script not long ago where a meathead character would pepper his speech with “you know” every five seconds, even when he didn’t need to. Or, to compare similar characters, there’s the character of Emma in the TV show, The Bates Motel. Like Rose, she needs a breathing apparatus.

Emma is infatuated with Norman, so every part of the way she speaks is geared towards pleasing him, impressing him, trying to get him to notice her. There’s a neediness to her speech pattern that brings her dialogue alive. Here in “Reap What You Sow,” characters speak mainly to move plot along or give opinions about things (i.e. “I don’t like Butch.”). There’s a lack of naturalism and a lack of fun to the dialogue.

And I don’t think this being a TV movie should be an excuse to write less-interesting dialogue. Sure, the dialogue’s probably going to be more on-the-nose than in, say, a David Fincher film, but you should still try to be on-the-nose with some flair.

I guess the best way to sum up my reaction to the dialogue here is that it felt like Brett was bored writing it. I want him to write a version where it feels like he’s having fun. And isn’t that what Lifetime wants anyway? Don’t they want a little cheese? A little goofiness? A little flash?

It’s nearly impossible for me to give a rating here because I’m trying to rate something that embraces a lower quality product. And while I definitely thought there was a lot to celebrate, the story wasn’t challenging enough to keep me engaged. That and the dialogue were what kept this from being “worth the read.”

With that said, I feel like Brett achieved what he set out to do, and I don’t see his script as being that far behind what Lifetime puts on the air. What did you guys think?

Script link: Reap What You Sow (new version)

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Brett hooked me up with a couple of writers who have operated in the Made-For-TV-Movie world. After promising each of them a box of Sprinkles cupcakes, they’ve shared with me some trade secrets. They say that Hallmark responds to scripts that promote the wholesome, family love, uplifting thing. While Lifetime is a little more varied. They prefer the tawdry woman in danger scenario. But also like domestic strife, standing up to invaders, and the storybook romance (an old flame rekindled). Any made-for-TV movie fans here? What other secrets can you tell us!?

Last week I went all doom and gloom on you guys, giving you the ten specs-turned-movies that have placed us smack dab in the middle of a spec sale wasteland.

And I get it. Buying specs is a speculative business. A spec hasn’t proven itself to be successful in any other medium. So it makes sense, then, that picking a winner would be tough.

But as I’ve always maintained, the movie business is cyclical. Tastes change. Strategies change. There was a time in town when if you weren’t making a Western, there was something wrong with you. Try to push a Western through the system now and see what happens.

So the spec will have its day in the sun again. We just need a few spec hits to bolster the confidence of the execs making the decisions. And it will be up to you guys to provide those ideas. And to get you motivated, I’m giving you ten spec screenplays hitting theaters over the next couple of years that could change our fortunes.

A few of these movies will have to WAY over-perform and they’ll have to do so in close proximity to one another (Hollywood tends not to change unless it’s shocked into doing so). But if you show them that there’s money they’re leaving on the table? You’re damn skippy they’ll start buying specs again.

So with that in mind, here are those ten scripts, ranked in importance from lowest to highest. May every one of them make the box office their bitch!

10) The Last Witch Hunter (not reviewed)

Writer: Cory Goodman

Logline: (from IMDB) – The last witch hunter is all that stands between humanity and the combined forces of the most horrifying witches in history.

The Skinny: Getting a handle on this film is a little like trying to stab a peanut with a fork. No matter how many times you try spearing the thing, it keeps slipping away. It looks like they’re hoping for an Underworld like franchise here, but the Lionsgate angle has me worried. In the past, they’ve buried their genre ideas under a lot of murky CGI and dark shadows (i.e. Priest). The trailers for Witch Hunter look pretty good though. I’m hoping Lionsgate is taking some of that Hunger Games money and investing it back in their product. We shall see.

9) Burnt

Writer: Steven Knight

Logline: A selfish workaholic chef tries to get back into the restaurant game after a much publicized meltdown years ago.

The Skinny: For those who have been following Scriptshadow from the beginning, you know this project as, “Untitled Chef Project.” It’s a great freaking script but has had a lot of directors and actors attached to it before finally grabbing Bradley Cooper and getting a green light. This would seemingly be a good thing, as Cooper is one of the top 5 biggest actors working today. But what made this script so good was how dark the main character was. I like Cooper but I’m not yet convinced he can go to those places. My fear is that they play this more like a traditional romantic comedy, and that would be death for the project. You have to stay true to what made the material stand out in the first place.

8) In the Deep (reviewed in the Scriptshadow newsletter – sign up!)

Writer: Tony Jaswinski

Logline: When a young woman goes surfing by herself in a remote location, she finds herself being stalked by a shark.

The Skinny: This is one of the higher profile spec sales of the last couple of years. And since people freaking love sharks, this movie will definitely find an audience. The question is, how big will that audience be? This isn’t a sprawling story involving an entire town, a la Jaws, but rather one day with one woman who spends large swaths of time clutching a buoy. It’s decidedly more contained. Then again, a little movie called Gravity was about a single woman stuck alone in space.

7) Holland, Michigan

Writer: Andrew Sodroski

Logline: A Midwestern wife/schoolteacher begins to suspect that her husband’s cheating on her, so enlists the help of a fellow teacher she’s developed feelings for to catch him in the act. What she finds instead will change her life forever.

The Skinny: Audiences seem to love serial killers, despite how disturbing the thought of that is. In this top-ranked Black List script, Bryan Cranston plays our husband. Now before you roll your eyes and think this is yet another “Look at me, I can play a convincing serial killer” actor vanity project, know that this is one of the more original screenplays I’ve read. It’s dictated by mood and unpredictability and a story that constantly keeps you guessing. The wild card here is director Errol Morris, who’s found fame mainly through documentaries. But if he can bring the cinematic vision he brought to his breakout doc, The Thin Blue Line, there’s a very good chance this movie could be awesome.

6) American Ultra

Writer: Max Landis

Logline: A psychologically damaged slacker living in a small town with his girlfriend, soon finds that the CIA is trying to kill him for reasons unknown.

The Skinny: Say what you will about the Maxter and his narcissistic online rants, but the guy’s sold a ton of scripts. And he has a talent for finding marketable pockets in the Hollywood system that haven’t been exploited yet. This take on a Jason Bourne like story where the main character is a stoner is a fresh perspective that we haven’t seen yet. True, I didn’t love the script, but a big reason for that is I’m not into pot humor. And my friends who ARE into pot humor are telling me this looks hilarious. If Jesse Eisenberg can bring what he brought to Zombieland, American Ultra could be the sleeper hit the spec market needs. And that’ll keep the Landis Experiment going!

5) Sicario

Writer: Taylor Sheridan

Logline: A female FBI agent is dragged into an undercover operation to take down one of the biggest drug tunnels in Mexico.

The Skinny: A lot of people are calling Denis Villeneuve the closest thing we’ll get to the next David Fincher. And you can already feel that. When Denis attaches himself to a project, everybody notices. This is great news for us spec screenwriters. Because even though I really liked Sicario, a part of me said, this could just be another run-of-the-mill border drama. Then I saw the trailer for the film and said, “Holy Shit.” This is a contender. Which is probably why they’re opening the movie this fall, right in that sweet spot where the Academy starts paying attention.

4) Bob the Musical

Writer: Multiple

Logline: When a buttoned-up company man is involved in an accident, the world around him becomes one giant musical number.

The Skinny: This project has been around for so long, I don’t even know who first wrote it. But it recently signed Tom Cruise up for the lead, which means we’re finally going to see the film. I may not have loved Rogue Nation, but like Will Smith and Denzel Washington, Tom Cruise (All You Need is Kill, Oblivion) is one of the few actors willing to take risks on non-IP material. As tough as this will be to pull off, it’s the kind of idea that if the elements do come together, it will be, as Lester Burnham says, SPECTACULAR. And when something this funky does well, it opens the floodgates for the industry to take lots of chances.

3) Collateral Beauty (reviewed in Scriptshadow newsletter – sign up!)

Writer: Allan Loeb

Logline: When a stubborn boss refuses to sell his company and make everyone in it millionaires, his employees devise a cruel plan to remove him from his position.

The Skinny: This was the highest profile sale of the year by far, selling for north of 2 million dollars, I believe. The script is very different, very unlike anything else out there. So it’ll come into the market with a zesty freshness the audience isn’t expecting. Will Smith has recently joined the project and the director of Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl, Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, will direct. This is one of those scripts that’s so unique that it’s either going to connect and become a sensation, or be so weird, it’ll turn everyone off and become the unofficial sequel to Seven Pounds. Let’s hope the former happens.

2) Section 6 (not reviewed)

Writer: Aaron Berg

Logline: The origin story of the British Agency, MI:6.

The Skinny: Universal bought this script for 7 figures, making its unknown writer a star. The project hit a legal snafu when MGM sued for infringement on its Bond franchise. But when the prospect of defining for all future interested parties the specifics of what did and did not constitute “James Bond,” they dropped that case quick. This project has two of the hottest young properties in the business on board, future star Jack O’Connell (Unbroken) and everybody-wants-him-due-to-his-massive-geek-cred director Joe Cornish (Attack the Block). If done right, this could feel like an old school James Bond film. Universal has the magic touch at the moment, so there’s reason to believe!

1) Passengers

Writer: Jon Spaihts

Logline: A spacecraft transporting thousands of people to a distant planet has a malfunction in one of its sleep chambers. As a result, a single passenger is awakened 90 years before anyone else. Faced with the prospect of growing old and dying alone, he wakes up a second passenger who he’s fallen in love with.

The Skinny: This spec, which was written almost 8 years ago now, is the project that made Jon Spaihts the go-to sci-fi writer in town. Your sci-fi project wasn’t legit unless you’d hired this guy. The script has just been impossible to make because it costs so much for a sci-fi movie that doesn’t have all the things in it that sci-fi audiences crave in order to put down their 12 bucks (aliens, space battles, adventure). This is a love story set in space. That made it unique as a spec but a nightmare as a studio project. For that reason, it literally needed the two hottest male and female movie stars in the world (Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence) to finally get a green light. The Imitation Game’s Morten Tyldum will bring the vision this film needs to navigate its complex themes of love, time, and loneliness, and hopefully, it all comes together. This really is the movie that needs to hit big to give the spec market life. Outside of maybe Killing on Carnival Row, there isn’t a spec out there that readers haven’t wanted to see turned into a film. It’s time to find out if that desire was warranted.

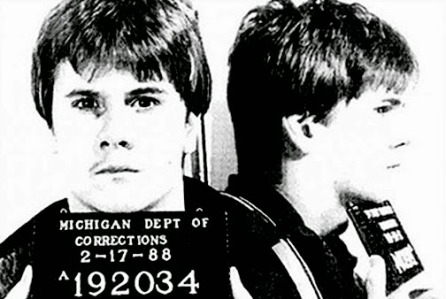

Genre: Biopic

Premise: At age14, Richard Wersche Jr. became an informant for the FBI. He spent the next two years helping take down the biggest drug gang in Detroit, Michigan.

About: There are THREE “White Boy Rick” projects in development, although this one, by most accounts, is the best of the bunch (so far). What’s interesting here (and a reminder for writers who like biopics but are afraid of copyright issues) is that writer-bros Logan and Noah Miller sold this as a spec. They didn’t have any rights to Wersche’s story. To be clear on that, nobody requires you to get the rights to a life in order to write a script about them. You can write the best biopic you can, and leave the “rights” issues to the production company and/or studio that buys the script. Logan and Noah Miller are probably best known for their 2013 indie film, Sweetwater, a Western that starred Ed Harris and January Jones.

Writers: Logan & Noah Miller

Details: 136 pages (undated – but the script went out in February of this year)

When not one, not two, but three production companies are all racing to make a movie about the same person, you figure that person’s life has to be pretty extraordinary. For that reason, I went into this screenplay with some high expectations. And you know what they say about high expectations?

It’s 1986 and 14 year-old Richard Wersche Jr. has the geographic lack of fortune to be born in one of the worst cities in America – Detroit. Detroit used to be the chest-puffed-out capital of the automobile industry. That is until the Japanese started making cars that were cheaper and better.

When that industry broke down, Detroit became a haven for gangs and drugs. But where there is chaos, there is opportunity. And Richard Wersche’s father got the idea to start selling guns to gangs. It’s not exactly legal, but it keeps food on the table. And who’s dad’s best employee? Wouldn’t you know it. It’s his son, little White Boy Rick.

One day Dad gets a knock on the door from the FBI. They know that if there’s anybody who’s got a beat on these gangs, it’s the man selling them guns. So they offer money to dad if he can give them the inside scoop. However, to their surprise, it isn’t Dad who knows everything about every customer, it’s his son, 14 year-old Rick.

As soon as the Feds realize that Rick’s a mini-Einstein, they employ him to infiltrate the drug community. This leads to Rick meeting the Curry Brothers, the number one dealers in the city, and three of the most dangerous motherfuckers you’ll ever cross paths with. The Curry Brothers like Rick. He’s an anomaly. A little white teenage brat who thinks he knows it all. That’s enough to embrace him and make him a key piece of the enterprise.

The movie then follows this little 14, then 15, then 16 year old kid as he’s pulled back and forth between the government and this gang, both of them taking advantage of and exploiting Rick. But Rick figures out a way to rise above it all. And when the Curry Brothers finally get caught with their hands in the crack jar, Rick’s there to take their place, becoming the biggest dealer in the city.

But then there’s no one left for the Feds to take down except for, ironically, the boy who got them there. So Rick is thrown into prison for the rest of his life, and not a single one of those Feds who used a minor to do their jobs ever got punished for it. Rick is still behind bars today, waiting for justice to be served to the men who took advantage of him.

I don’t know if White Boy Rick is a great script so much as it is a great real-life story. And this is what I keep telling you guys is the dirty little secret of screenwriting. If you find that awesome idea or that awesome character, the script will write itself.

I mean we have a 15 year-old taking down some of the biggest drug dealers in the country. He becomes a millionaire, making more money a month than, as he points out, the president of the United States. He ends up running the biggest cocaine trading pipeline between Miami and the Midwest. He’s used by both sides of the system. He USES both sides of the system. It’s no secret why three separate companies are rushing to turn this man’s story into a movie.

White Boy Rick also taught me that utilizing an “impending sense of doom” shouldn’t be limited to horror films. Here, the impending sense of doom is the main story element driving us to keep reading. We know that Rick can’t walk this line forever. Either the bad guys are going to figure out he’s playing them or the good guys are going to stop needing him, and when either of those things happen, he’s toast.

To that end, this script did a great job. I wanted to see how Rick would fall.

If the script has faults, though, it’s its unabashed desperation to land Scorsese as a director. Because Scorsese has made this film so many times now, what was once a unique product has become pure formula. Not unlike the “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back” formula that drives a rom-com, the Scorsese Tragedy has its own familiar beats. And while Rick was an amazing character, you couldn’t help thinking of Goodfellas, or The Wolf of Wall Street, or Casino, when you read White Boy Rick. It almost feels like one of those scripts was chosen and these new words were simply pasted on top of the old ones, starting with the obligatory first act of pure main character voice over.

It’s a writing crutch we all fall back on. When we write a movie, the first thing we do is go back and watch all the similar movies to see what they did right. The problem with this approach is that, whether you’re aware of it or not, those story beats are seeping into your soul, and without you even realizing it, you’re soon copying those beats into your script. So sure, you may be doing what made that other movie work, but you’re doing so at the expense of originality. You need to deviate from the script sometimes, pun-intended.

Despite the familiarity of the formula, I’d still recommend this script because the title character is so freaking fascinating. You can’t believe this really happened. And the Millers did an excellent job of making Rick likable. This guy did some horrible things. He ran a drug organization that indirectly killed hundreds (maybe thousands) of people. Yet the Millers cleverly present Rick as the victim, the teenage boy who was taken advantage of by everyone in his life, even his own father.

And maybe that’s the lesson to take away from this. When you have an idea this good or a character this good, you can make a lot of mistakes in your script and the script still works. If you have a flimsy or light premise like, to use a random example, Enough Said (that rom-com with James Gandolfini and Julia Luis-Dreyfus), the tiniest mistake (a boring twist) could derail the entire story. White Boy Rick proves what happens when you have the ultimate subject. Much like Rick in real life, the script becomes bulletproof.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A common mistake I see in monologue-writing is the writer getting too wrapped up in what the character is trying to say, and then delivering an overly-rewritten on-the-nose monologue that’s boring as hell. Monologues are always more memorable when they’re unique, or, like a good story, deviate from the expected path. To that end, I loved this monologue in White Boy Rick. In it, one of the FBI agents asks Rick if he knows who Nancy Reagan is. Keep in mind that the point of the monologue is to convey how important it is (to both Rick and us) that the government win the war on drugs. Most writers would’ve written a very straight-forward dull message about how the war on drugs is destroying America and if they don’t do something soon, the fabric of the country will be permanently destroyed. Here’s how the Millers write it instead. AGENT TURNER: “Well, it turns out that the First Lady is very fucking angry these days. She’s so fucking angry that she’s declared war. A War on Drugs. You know what that really means? That means that if she doesn’t get what she wants, if she doesn’t win this fucking goddamn war, the President doesn’t get any pussy. She locks his dick out of her vagina. And that’s bad for the country. Hell, it’s bad for the whole fucking world. Because when the President of the United States of America ain’t getting laid, he gets really fucking frustrated, and the next thing you know the nukes start flying and we’re buried in World War III with the fucking Russians.”

Genre: Noir/Superhero

Premise: A unique interpretation of the Superman vs. Batman story that reinvents the characters and cleverly avoids outright association with either property.

About: Screenwriter Jeremy Slater has the dubious honor of having his name attached to the biggest bust of the year, Fantastic Four. But there were some extenuating circumstances. First of all, whatever movie Slater wrote clearly isn’t the one that showed up at theaters this weekend, as the film has been famously repurposing itself over the last six months. And second, just being asked to adapt a major franchise is a HUGE EFFING DEAL as a screenwriter. It’s the equivalent of what used to be the big spec sale. It means you’ve arrived. And Slater got this job by writing the screenplay I’m reviewing today – a screenplay that many consider to be one of the best in Hollywood.

Writer: Jeremy Slater

Details: 2012 draft

Man of Tomorrow has been slip-sliding around in my read pile for the better part of 3 years. At some point, I just forgot what it was about and it slipped into read purgatory. Then the script came up in a few recent conversations and people were like, “You haven’t read Man of Tomorrow??”

The record scratched. Everyone in the room turned. My script ignorance was put on blast – not something I’m used to. I know the script was on the Black List a few years ago but wasn’t it somewhere near the bottom? That was all part of the mystique that surrounded Man of Tomorrow – mystique that would play into this dark and unpredictable read.

The year is 1946. 50-something Paul Harrigan is an FBI agent who’s been tasked with the impossible – containing Tommy Anders, the man who has taken over Chicago and turned it into a spot so crime-infested that even Al Capone would be disgusted with it. And Al Capone actually makes an appearance in this movie so a reaction like that is possible!

The reason Tommy can just take over a city is because he possesses super-human powers. He’s stronger than a thousand men. Bullets bounce off his body. And rumor has it he can even fly. But unlike his doppelganger, the superhero who shall not be named (his name rhymes with buperban), Tommy uses his powers for naughty reasons, namely running the biggest criminal organization in the country.

Tommy’s only problem is that a not-so-nice man named Erinyes doesn’t like him. Erinyes is a psycho with a gravelly voice and a silver mask who keeps killing Tommy’s men. His message is a simple one: “Get the hell out of Chicago or Ima gonna make you dead.” My words not his.

While Tommy doesn’t want to admit it, Erinyes is the first mortal he’s ever been afraid of. More specifically, he’s scared Erinyes will kill the love of his life, Lili. You can’t stop bullets if you’re not around when they’re fired.

What follows is a story surprisingly full of twists and turns that plays out under a Pulp-Fictionalized timeline, one that jumps back and forth to tell its story out of order, as if the script hadn’t catered to the geek populace enough. When it’s all said a done, Hitler, Al Capone, a nuclear bomb, and lots of heavy shadows will make cameos in “Man of Tomorrow,” a non-traditional script if there ever was one.

So there’s this growing contingent of people out there saying that since the spec script is dead, there’s no reason to try and write a script to sell anymore. It makes more sense to determine what kind of movies you want to write in Hollywood, then write a really weird out-of-the-box story that exists adjacent to that universe.

So if Jeremy Slater wants to write a Superman movie, it doesn’t make sense to write a movie about a superhero who saves the day. That’s every superhero movie ever. Instead, set your story in the 1940s. Create a Superman vs. Batman storyline, but rename the characters and modify their powers a bit. Throw in a film noir style and jump around in time to really shake the story up.

Now you’re got something that shows you can write a superhero movie, but you’ve also proven that you have a unique voice and that you think outside of the box.

To this strategy I say… hold your horses. I still think you can sell scripts if you target genres that are still selling (Thrillers, Horror, Comedy) and you execute them well. I also think there’s a fine line here. Man of Tomorrow shows what happens when a writer executes this strategy successfully. But I read the 100 other scripts that execute this strategy miserably.

Cause the thing is, just being different isn’t enough. You still have to know how to tell a story. And I can tell that before Slater wrote this screenplay, he wrote plenty of traditional scripts. It takes control to be able to jump back and forth in time and not lose the reader. It takes skill to create characters with as much depth as these (Harrigan is drowning in internal conflict, and both Tommy and Erinyes have extensive and heartbreaking backstories).

The point is, yes, writing something outside of the box is good, but you still need a solid understanding of storytelling to pull it off.

This leads us to the more pertinent question of is today’s script any good on its own (regardless of its weird approach)? I’d say yes, but I didn’t like it as much as everybody else seemed to. And everybody else REALLY seemed to like Man of Tomorrow (writers have literally said to me: “You haven’t read Man of Tomorrow?? Cancel the rest of your day and read it now!” “But I have a doctor’s appoint—“ “CANCEL IT NOWWW!!!!”)

I think it’s because I’m not a film noir guy. I don’t like stylized reality (I’d rather have my skin peeled from my body via a potato peeler than watch a movie like Sin City). I like things to be as grounded as possible (unless the genre dictates the opposite, like Star Wars). And I detest alternate history. In this script, Tommy kills Hitler and wins World War 2. Erinyes is the creator of the atom bomb, which he plans to use to kill Tommy. It was all a bit too geeky for me.

But there’s no question, when you read “Man of Tomorrow,” how much skill is on the page. Here’s a random sample of the writing I copied from page 3: “The old guy still has a flair for the dramatic. He pauses to light a cheap cigar, takes a few puffs, exhales greasy smoke through his teeth. Never taking his eyes off Tommy.” That level of detail is far superior to what I usually read, which is something closer to this: “Our hero is smoking as he stares at the other man. He looks him hard in the eyes. There’s a clear dislike between the two here.”

So if I had a higher Geek degree, I’d probably be giving this five stars. But from where I stand, I’ll have to appreciate it more from afar. Which is still pretty impressive when you consider I’m generally not a fan of this stuff.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The right action, no matter how tiny, can sell an entire character, which can be critical early on in when you need to convey newly introduced characters quickly. Let’s look at the very first action of our hero, Harrigan: “We find HARRIGAN shoveling a porterhouse steak into his mouth.” Reread that and pay close attention to the details. The verb “shoveling” indicates aggressiveness. And a “porterhouse steak” is a very masculine food. 10 words! 10 words is all we needed to give us a sense of this character. To bolster this point, consider how differently you imagine Harrigan when I introduce him this way: “We find Harrigan nibbling on a cucumber roll.” You’re imagining a completely different character, right? That’s how important actions (even tiny ones, like how they eat) are in selling your characters.