Genre: Sci-fi/Thriller

Premise: In the future, crime-fighting has been taken to the next level with “Vision,” a government project that allows specially trained agents to watch everything we do – and it’s all totally legal.

About: “Vision” went out a month ago and while it hasn’t sold yet, it probably will. Writer-director brothers Alex and David Pastor already have a big writing project coming out, Self/Less, which stars Ryan Reynolds as a body-hopper. I think with Vision they plan to direct it as well, which should push it through the system a lot faster (a naked spec takes forever to move through development – if you have directors attached, that eliminates half the battle). The Pastors first broke on the scene with their 2009 horror film, Carriers, which starred Chris Pine and followed four friends fleeing a viral pandemic.

Writers: Alex & David Pastor

Details: 108 pages (revised draft – 4/29/15)

So the other day I wrote an article about “spec-friendly” screenplays, the type of screenplays that do well on the spec market. These scripts are fast, fun, and easy to grasp.

Which stands in stark contrast to scripts built off of book adaptations, or assignments that come through the studio and prodco systems. In those environments, you’re working with people who are guiding you. They are therefore more patient and open to complicated story developments (and actually might encourage them).

Vision plays in the Sci-fi and Thriller genres (two genres that sell a lot of scripts), it’s really fast (you’ll struggle to find any paragraph over 3 lines), the script is built on a clear strong goal, it’s got loads of urgency, it doesn’t require a ton of concentration to keep up with – in that sense it’s about as “spec-friendly” as a script can get.

So then why didn’t it work for me? Well, it turns out that all spec-friendly screenplays have one giant weakness – a pitfall that’s easier to fall into than a never-used gym membership. What is that pitfall? Let’s discuss Vision’s plot first and then we’ll work on saving you from imaginary workouts.

The year is 2034 and the Snowden sub-culture that scared the bejeezus out of the average American in 2015 has morphed into something far freakier. Back in 2024, there was a nuclear attack on Chicago that killed a million people. After that, people were willing to give up a little freedom if it meant plutonium-free trips to the park.

And hence the Vision Project was born. Vision allows specially trained agents to watch over every single camera in the city to identify crimes before, during, or right after they happen – allowing cops to catch criminals instantaneously.

Our Vision controller protagonist is Leo Kruczynzki, a 35 year old guy who believes in the cause. And he’s good at what he does. The opening sequence shows Leo tracking down a murderer using a number of visual and aural monitors throughout the city (he locates a gun shot by triangulating the sound through three separate pedestrian recordings). In conjunction with his ground agents (every Vision Jockey needs’em), Leo’s pretty much unstoppable.

But everything changes when Leo spots Amanda, his former wife who disappeared on him one day. The red-headed Amanda has just been involved in a cop shooting. She makes a run for it and Leo must decide whether to use his fancy-schmancy Vision tools to capture or aid her.

Using some Vision magic, he gets Amanda on the phone, where he learns she’s part of a resistance and she’s found evidence of some major government plan – evidence the government will do anything to destroy.

So Leo has to make a choice – ditch his superiors and join the resistance – or do what’s “right” and protect the American people.

So what’s that big danger when writing a “spec-friendly” script? Simple.

GPS (GENERIC PLOT SYNDROME)

When your story moves spec-quickly, when your description is limited, when you’re playing to the impatient crowd, there’s not a lot of room for character exploration. Character development is mostly relegated to character choice, character action, and character reaction. And while you can still do a lot of cool stuff with those options, you’ll never have that scene in American Beauty where a character breaks down while watching a video of a bag flying in place.

And “Vision” falls victim to that in a big way. My biggest fear when opening this was that it was going to be Eagle Eye 2. And while we’re approaching those themes from a slightly different angle, that’s basically what it is. A lot of running around with very little plot and almost no ingenuity.

When you’re writing that spec thriller, I think the one area where you can stand out is in your plot choices – in the ways you twist and turn and evolve your plot. Because, as we’ve established, it’s hard to do much of anything anywhere else. So I was hoping for more exciting twists and turns here, plot developments I hadn’t seen before. Instead I got the standard:

1) Someone knows a secret about the government.

2) There’s a flash drive that contains this information.

3) They have to find the flash drive.

4) The flash drive says the government is going to attack the people.

5) Our protagonist has to prevent the attack.

The story beats here were just too “Screenplay 101 3-Act Thriller.”

I know some people didn’t like the Source Code film, but Source Code the spec was one of the best specs ever written. And a big reason for that was that they played with the plot more. They developed rules (the mission resets every 8 minutes – our main character stuck in a mystery bay) you weren’t used to, which allowed them to go places that kept surprising you.

Vision was the opposite. It was set up as a standard thriller from the get-go and it never tried to be anything more than that. Which was frustrating. I think one of your duties as a writer is to anticipate what the reader/viewer is expecting and then GIVE THEM SOMETHING ELSE. I’ve seen Tarantino mention this approach in a number of his interviews. I just wish more writers would challenge themselves to do the same.

With that said, this script is still a better read than your average amateur thriller. We may know what’s going to happen, but the writing is slick. The beats come at you when they’re supposed to. There’s an urgency here (the entire thing is basically happening in real time) that makes the story move. It feels like a screenplay, and more importantly, a movie. So there is something to learn as a writer.

But it’s one thing to write a screenplay that looks and feels like a professional screenplay. It’s quite another to write a screenplay that surprises, moves, and wows people. I wish the Pastor brothers took a bit more time and tried to make this the latter.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Every thriller needs that “there’s no going back moment.” You need to add that scene where your protagonist does something where going back to his normal life is now impossible. That way, we know he’s fucked and that he has to commit to the cause. This raises the stakes considerably. Here in Vision, one of Leo’s co-workers walks in and sees that he’s working against the company. Leo makes a quick decision to kill his co-worker. There’s definitely no turning back after that.

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

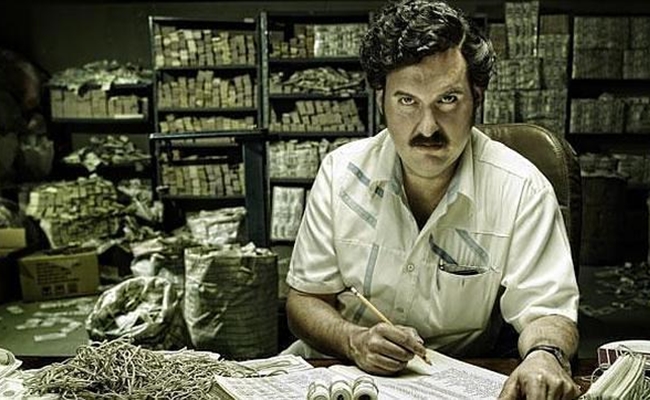

Premise: A show that follows the DEA’s attempts to take down one of the most notorious drug lords in history, Pablo Escobar.

About: Narcos is the newest show to come to Netflix (it debuts in late August) and is written by Chris Brancato, an extremely successful TV writer who most recently penned a bunch of episodes for NBC’s well-received Hannibal. It’ll be directed by Jose Padilha, the director of the recent Robocop reboot.

Writers: Chris Brancato

Details: 53 pages – May 13, 2014 draft

You know, it’s funny. I started reading an older draft of Narcos, only to be sent the newest draft before finishing, which turned out to be a complete page 1 rewrite. And holy shit, what a difference a new take makes.

Of all the ways to learn screenwriting, one of the best ways is to read two takes of the same idea. Because you can see, right there with your own eyes, how drastically different choices affect the material. You can see how one writer’s ideas can build a promising story while another’s can doom it.

In the case of the old Narcos draft, it was about as generic, safe, and predictable as a storyline about the Columbian drug trade could be. We meet a drunk Austin DEA agent. He’s depressed. He gets a new assignment. Go fight drugs in Columbia. He goes there, starts learning the trade.

Meanwhile, we introduce 700 other characters of two different ethnicities (foreign character names are harder for readers to keep track of due to the lack of familiarity), without ever establishing a clear storyline or point other than the vague, “Let’s stop drugs.”

There wasn’t an ounce of creativity and the pacing was more glacial than a Terrance Malick director’s cut. Enter Brancato’s take, which was 180 degrees different.

Instead of moseying through lazy character introductions and taking forever to get to something interesting, he embraces the Martin Scorsese approach, giving us a pilot-long voice over from DEA agent Steve Murphy. Unlike the other draft, where we spend 20 pages just getting to Columbia, Brancato has us there on page 1.

Through Murphy’s voice over, we learn the fascinating backstory of how Columbia became the cocaine capital of the world. Chile was actually the number 1 cocaine dealer for a time, but when Nixon cozied up with the Chilean president and asked him to “just say no,” the president killed the country’s band of drug lords in one fell swoop.

That is, except for one man, a survivor named Mateo Moreno who was appropriately nicknamed, “The Cockroach.” Mateo figured out that the number one smuggling nation in the world was Columbia. That made them the perfect fit for his new star drug.

So he went there and eventually hooked up with Pablo Escobar, the number one smuggler in the country, and the two began building an empire. Escobar figured out right away that Columbia could only pay so much for the drug. If they wanted to make big money, they needed to export to America.

Which leads us to how our hero, Steve Murphy, got involved. After Escobar kills The Cockroach in a dispute over money, the guy becomes a megalomaniac, taking an aggressive stance against anyone who challenged him, a stance that would lead him to kill over 1000 cops during his rein.

Will Steve Murphy be one of those cops? Or will he be the man who finally takes the legend down?

So like I said, the rewrite of Narcos was a thousand times better than the old draft and that’s because Brancato realized what was interesting about this world – Pablo Escobar. If he’s going to sell you on this series, he needs to sell you on this man – not the 85,372nd depressed alcoholic cop protagonist in the history of television.

But this approach comes at a price. Because the entire pilot focuses on how Columbia became the cocaine capital of the world , we don’t really get to meet any of our heroes. And that would be cause for concern… if this weren’t a Netflix series.

It used to be, in the traditional television model, that you had to have a super awesome self-contained pilot episode that ALSO set up a series. Because if people didn’t like your pilot, they didn’t tune in the following week, and your show was dead.

With Netflix, they just throw all the episodes up at once, creating one long extended movie. So Brancato, no doubt, realized he had some leeway with his pilot. He could forego setting up all his characters and instead set up his world. Then he’d use the second episode to introduce his crime-fighters.

Does this mean you should start doing the same? Uhhhh, no. If you’re writing a pilot, stick to the network model for now. You definitely want to set up all your main characters. The only way you should be pulling a Narcos is if Netflix has already greenlit your show (or HBO, or one of these other “special engagement” 8-10 episode series).

Now some of you craftier Scriptshadow readers may have noticed that yesterday I was telling you to SLOW DOWN. That the story was moving too fast. Whereas here, I’m saying the pilot didn’t work until they sped it up. What gives?

Well, speed and pacing and how quick you move will always depend on the individual story you’re telling. Yesterday’s script was begging for a slow burn. We needed to feel safe before the fear could creep in. Today’s script, with its complicated subject matter and potential to get bogged down in details, needed more thrust.

As the previous writers proved, moving slowly through complicated drug agency parlance and multiple drug organization hierarchy did nothing but put us to sleep. By instead saying, “Here’s this super interesting dude named the Cockroach who survived a mass assassination attempt by his country then fled to Columbia to start one of the biggest illegal industries in history” – I’d say that’s a bit more exciting and more likely to draw viewers in, no?

Now does this mean Narcos couldn’t have worked with ANY slow setup? Of course not. A different writer could’ve constructed a slow burn that was a lot more exciting. And actually, now that I think about it, the biggest problem with that old draft was how not a single character stood out. They were all cliché bland to the fucking max.

Go read Allan Loeb’s latest spec – Collateral Beauty – to see how to achieve the opposite. But point being, the slow setup with boring characters doomed the early draft of Narcos. And kudos to Netflix for recognizing that and starting over. Cause that previous draft was unsaveable.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dialogue that sounds authentic is good. Dialogue that sounds authentic at the expense of being clear is bad. This was another big problem with the early draft of Narcos. A lot of characters saying things I didn’t understand. Here’s a common exchange:

BARNES

We’ve been working this place for months. Title Three intercepts, trap and trace. Whole nine.

PENA

How’d you get up on them?

BARNES

CI.

I read enough exchanges like this and I’m falling asleep (which I did!). Sure, they sound wonderful. But they mean NOTHING to me cause I don’t have the slightest idea what the characters are talking about. Sound authentic but NEVER at the expense of us knowing what the characters are saying.

The Scriptshadow Newsletter is Out! If you didn’t receive it, check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders. It should be there. And it’s a good one. I review the hottest screenplay in town!

Genre: Thriller

Premise: When a newly minted partner at his firm goes to spend the weekend with his old friends, the three of whom own a successful hedge fund, he begins to suspect that they’re involved in some major illegal activity.

About: The 1983 film, The Osterman Weekend, is probably best known for being directed by the legendary Sam Peckinpah, as well as having a stellar cast (Rutger Hauer, John Hurt, Craig T. Nelson, Dennis Hoppper, and Burt Lancaster). It was around 2007 when people first got the idea to remake the film, and since then, it’s gone through a series of rewrites and restarts. The original book was written by Robert Ludlum, who’s best known for birthing the Bourne franchise. This is the most recent known draft and was written by Jesse Wigutow, who’s been doing well for himself lately. He wrote the latest Tron movie before it was cancelled by Disney. And he also wrote the latest Crow film, which we’re being told is coming soon.

Writer: Jesse Wigutow (based on the novel by Robert Ludlum)

Details: 121 pages- 6/12/12 draft

I think it was Steven Soderbergh who once said, “Why do we keep screwing up all these classic movies. If you’re going to remake a film, find one that had a good concept but bad execution.” In other words, find great ideas that they screwed up. And that appears to be the idea with an Osterman Weekend remake, a 1983 film that was loved by, well, nobody.

But I’m a big fan of these types of ideas. Seemingly small films with big concepts at their core – high stakes, the potential for lots of conflict and surprises. A guy stuck in the middle of nowhere with friends who may or may not be planning to kill him? That’s a movie there. In fact, this is the exact type of idea I’d like to see in a Scriptshadow 250 entry. Cheap to shoot but bursting with ideas inside.

Does The Osterman Weekend do its job and improve upon the original? Well, I can’t answer that question because, like the rest of America, I never saw the original. But now that I’ve read the script, I have a better idea of what may have held the film back.

The Osterman Weekend follows 35 year-old John Tanner, a tax attorney who’s just made partner. Tanner’s life is looking up, as in addition to his promotion, he and his wife are planning to have their first child.

Every year, Tanner heads up to an island off the coast of Maine, to join his three best friends – Loewy, Tremayne, and Osterman. The four of them descend back into their frat boy days, drinking, fishing, and generally being idiots. It’s a harmless weekend of rekindling their friendship.

Except this weekend isn’t going to be harmless. Loewy, Tremayne, and Osterman own one of the hottest hedge funds in the country. Their returns have been so incredible, they’ve left competing hedge funds in the dust.

On his way there, Tanner is confronted by a couple of men from Homeland Security, who inform Tanner that his buddies are bad news – they’re stealing money. And they want Tanner to help take them down.

Tanner’s not sure whether to believe this or not, but when the men tell him that Tanner could land in prison if he doesn’t help, he’s forced to wear a wire and collect intelligence on his buddies.

The weekend basically follows Tanner as he tries to extract information from his friends. As the weekend goes on, he learns that his buddies are involved in something far more complicated than simply building an elaborate money scam. And maybe their situation is more sympathetic than his pals at Homeland have made him believe.

Who does Tanner trust? Who does he help? In the end, he’ll have to decide whether to go with what’s best for him and his wife, or go with what’s best for the friends he’s known all his life.

When I heard about The Osterman Weekend, I thought I was going to get a really subtle thriller about a guy who ignorantly shows up at his buddies’ weekend party, only to slowly realize that they were criminals capable of doing something horrible – possibly even killing him. That’s the movie I wanted to see.

Instead, The Osterman Weekend comes at you like a giant hammer, banging its way into your skull. Gone is all hope of subtlety when before we even GET to the weekend spot, we’re already bombarded with two agents who are telling our hero that his friends are evil.

From that point on, I found myself completely distanced from the story. It was just so BIG and IN YOUR FACE. Even the writing screamed at you, with lots of CAPITALIZATION EVERYWEHRE YOU LOOKED.

Doesn’t this story work better if Tanner shows up on this island, thinking he’s in for a fun weekend, and then slowly discovers clues that his friends aren’t who they say they are? That they’re planning to do something horrible? And he has to quietly investigate what that is without them catching on? I think so.

Another frustrating thing about The Osterman Weekend was the lack of hand-holding. Whenever you’re covering a complicated job, or subject matter, or plan, it’s your duty as a writer to hold the hand of the reader and take them through the details so they know what’s going on.

The Osterman Weekend is about law firms and hedge funds, things I know next-to-nothing about. This left me playing “catch up” throughout most of the first act. In fact, since we were talking about hedge funds so much at the start, I thought Tanner worked at a hedge fund. It was only after a later throwaway line that I realized he was a tax attorney.

If the details aren’t important to the story, you can get away with less help. But the hedge fund here is the cornerstone of the plot. So to leave us on our own to interpret it was frustrating at best. Always be mindful of the fact that the reader knows less than you. If you have complicated subject matter, help the reader through it.

Maybe The Osterman Weekend’s biggest problem though – and the reason that despite a legendary director and stellar cast, it didn’t do well – is that it has a main character who doesn’t do anything. He’s just a pawn in the middle of two way more active parties.

It’s preferable you pick stories where your main character is DRIVING THE ACTION. He’s the most active party in the story. Here we have the Homeland Security guys (I’m still not sure why Homeland Security is trying to bust a hedge fund) targeting Osterman. We then have Osterman mounting a complicated escape plan. And Tanner is stuck in the middle, doing whatever people tell him to do. Someone needs him to wear a wire, he wears a wire. His buddies tell him the hedge fund issues aren’t their fault, he believes them.

This has been a debate since the beginning of screenwriting. Can your main character make it through an entire movie without being active? I suppose it’s possible but your audience is always going to respond better when your main character says, “Fuck this, if I’m going down, I’m going down my way.”

I mean look at Ludlum’s most famous series of novels. They revolve around one of the most active characters out there – Jason Bourne.

I think things are different in novels when you’re inside the hero’s head. We get a running commentary on what he’s going through. Therefore, it’s not as evident that he’s inactive. Because there’s all this activity going on in his brain. In movies, it’s different. All we have to go on are a character’s actions. So if they’re simply jumping when other characters tell them to jump, they look weak. And nobody likes a weak hero.

I’d love it if they went back and started from Square 1 here. Make this a slow-build story. Inject some curiosity and suspense into Tanner’s arrival. Make it so that everything seems great before everything falls apart. That was my biggest issue with Osterman. They introduced a problem before we had a chance to settle in and consider that there might be problems. There was no patience here.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Hold the reader’s hand when it comes to complicated subject matter. Tax attorneys? Hedge funds? The average person knows nothing about these things. So make sure you explain them to us, as well as how they fit into the story. If you leave us behind, we’ll mentally check out, and from that point on, we’re unable to enjoy your story.

We may have some good ones today. 16 year olds, both real and imagined. A xx worther who’s back for more. Girl on girl action. And an alcoholic minister. That sounds pretty turnt up to me (I just learned the phrase “turnt up” yesterday so I’ve been using it a lot. Also, “thirsty” apparently doesn’t mean “thirsty” anymore. I found this out the hard way when I casually discussed how thirsty I was to the female cashier at the supermarket. I’ve now been told that I’m “not allowed there” anymore. I’m very turnt up about the experience). Also, the Scriptshadow Newsletter DID NOT go out last night but should be blowing up your Inboxes this evening. In the meantime, let’s take a look at some amateur screenplays, shall we? For those new to the experience, read as many scripts as you can, then share in the comments which script you thought was best and why you stopped reading the others. Help these writers improve!

Title: MISSION STYLE

Genre: Comedy

Logline: An eccentric, alcoholic minister will either save his beloved mission from foreclosure or go to hell trying.

Why you should read: Mission Style is an unconventional, multi-cultural comedy that holds nothing back. This script was influenced by comedic great, Mel Brooks. It’s a light hearted, yet poignant snapshot of religion and culture that takes us back to when we used to laugh at our differences. — Mission style also placed in the Semi-finals in the Page Awards.

Title : Girl

Genre: Drama

Longline: A rich girl from Manhattan and a handsome law student’s preconceived view on gender and sex are shattered when they fight for the affection of a lesbian art activist.

Why you should read:

1. Equality without Exception San Francisco Pride @45 is this weekend.

2. The feature Girl was a semi-finalist in the 2015 Table Read My

Screenplay Competition.

3. Girl on girl action.

4. I have a MFA from CalArts but don’t hold that against me.

5. The script is fucking awesome.

6. See #3.

Title: Desiré’s Storm

Genre: Dramedy

Logline: A suburban father becomes infatuated with his wife’s sixteen year-old daughter during her unintended stay throughout a hurricane.

Why you should read: Hello Scriptshadow community! Longtime reader, first time submitter here. I’ve been writing for five years now with no luck. I’ve sent countless query letters and to my knowledge, no one in a position to change my life has even cracked open any of my scripts. — Sooooooo I’ve decided to grab my career by the balls. I wrote this with ME intent on directing it. Its a contained drama (it takes place in two houses), with some elements of comedy. And of course, I cannot finish without saying this story draws direct inspiration from one of my all time favorite movies, American Beauty with a dash of Eve’s Bayou. — Honestly, I don’t care much if I win AOW. Notes from the many wonderful readers of Scriptshadow is more than enough for me to get in one or two more drafts before I go and direct this bad boy!

Title: Because He Could Fly

Genre: Drama

Logline: The human race’s ability to create chaos and tragedy out of nothing is put on full display when the government discovers a man who can fly.

Why you should read: Because I am only sixteen years old, I have not been able to find a good service or person to review my script. The film industry is a tough one, and people aren’t willing to take a chance on such a young writer. Being a sixteen year-old screenwriter is a very discouraging road to travel, but it’s one I’ve persisted on for almost two years now. I guarantee that the time spent reading this through will be worth it. I’ve been working on this script since November and I’m confident in this script and my abilities as a writer. Because He Could Fly is ultimately a very thematic film, and I would hope that even if you don’t like it, you will be able to take away something from reading it, because that is my job as a writer– to give you something great to keep with you from your experience reading or watching my work.

Title: Unlawful

Genre: Mystery/Thriller

Logline: A troubled detective operates outside the law when he buys an underage prostitute to perform “favors.” But when a 16-year-old girl goes missing and he must use her diary to reconstruct the events that led to her disapperance, an unimaginable truth emerges.

Why you should read: You once wrote on your blog that you had passed along a script because it was RFG(Really Fucking Good). The person you sent that script to, agreed with you about it being RFG and they passed it along, etc. — Well, I’ve been told that my script is RFG and I’m passing it along to you as I’d like to see what the SS community thinks. — It’s a dark tale and honestly, I was in a fucked-up place when I wrote it. Hell, I still might be there. But while I love reading a good mindbender, I loved writing one even more.

Quickly, there will be NO AMATEUR FRIDAY POST TOMORROW. There will be Amateur Offerings Saturday morning, but that’s it. The good news is, I’m sending out a Newsletter tomorrow evening. So make sure you sign up to reap all the yummy screenplay-news benefits. Now on to today’s article!

The spec screenplay market has to be one of the most confounding, one of the most confusing, one of those most frustrating, markets in existence. You’d think all you have to do is write something slightly better than the last movie you saw and you’d be able to start cashing checks and put a down payment on that Bel-Air mansion Redfn keeps reminding you about. Yet time after time, aspiring screenwriters come to Hollywood writing multiple screenplays only to leave a couple of years later with their tail between their legs, attributing their failure to buzz words like “nepotism.”

What is the common mistake these screenwriters make that facilitates their failure?

They never learn the system.

In fact, they probably never even knew a system existed. Their understanding of a screenplay sale is based on a New York Times article they read once about a 3 million dollar spec purchase from a writer, the paper implies, who started screenwriting last week. Nowhere is it mentioned that the writer has actually been studying the craft of screenwriting for 15 years, has three previous sales, and has an amazing relationship with the studio he sold the script to that dates back a decade.

To be clear, most scripts sell through some version of this method. The writer will have a prior relationship with the producer/studio and the producer will say, “You know what I’d really like to make right now? A creature feature.” The writer then writes a creature feature with the understanding that, at least with this buyer, he has a good chance of selling it.

But this is not the system you, the unknown screenwriter, take part in. The system you send your scripts into is more like the Wild Wild West. Instead of known entities collaborating on potential projects they want to make, you’re an unknown entity screaming your idea into a void, hoping one of many others in that void hear you and scream back.

Once you understand that this is how the spec market works, you can start weaponzing your script to attack it. The idea is to write the ultimate “spec-friendly” screenplay, a screenplay specifically designed to do well within the unique parameters that make up the spec market. And this brings us to our first spec-friendly rule. If you’re going to yell your idea out in the hopes that someone yells back, you better make sure your idea is really fucking good. So, rule #1:

1) Generate a concept that’s going to excite people.

80% of spec screenwriters either don’t know the importance of this rule or ignore it. But it’s the heartbeat of every spec sale. Your idea has to be exciting. You guys see it every Saturday morning here on Scriptshadow. You gravitate to the bigger ideas, the bigger concepts, while ignoring the ones that sound bland, small, or uninspired.

What’s troubling is that half the writers out there KNOW that their ideas are small and they still write them, convincing themselves that they’re the “one exception.” Guys, we’re trying to arm our scripts here, not cripple them. If you’re not walking into the spec market with a big idea, it’s like walking onto the battlefield without a gun. You might as well just pose in the position you wanna be dead.

Once you’ve convinced someone to read your script based on that awesome idea, you run into a new problem – the Hollywood Reader, a perennially overworked and hard-to-please soul-crushing individual who may or may not drink the blood of failed screenwriters. The large majority of scripts readers read are terrible, so they’re pre-programmed to think that your script is terrible as well, putting you at an extreme disadvantage before they’ve even opened your screenplay.

What’s important to remember about the reader is that reading for him isn’t an enjoyable experience. Reading for him is work he has to complete by the end of the day. You know that work you’re doing right now? That document you have to send off to your boss or that TPS report you need to make copies of? Readers see your scripts the same way you see those TPS reports – they’re obstacles they must finish in order to get to the things they really want to do that day.

This is a major truth that the average screenwriter either doesn’t know or doesn’t want to acknowledge. That the person they’re giving their screenplay to is actually an ADD riddled fellow screenwriter who wants to whip through and cover their script in record time so they can start working on their own screenplay. And it’s this reality that dictates the bulk of the rules in writing spec-friendly screenplays. Here are rules 2-4, which help navigate this admittedly complicated problem.

2) Write a clear easy-to-follow plot. The heavier the plot is, the more sub-plots there are, the more subtle and nuanced the story beats are, the less of a chance your reader will understand what’s going on. With spec screenplays, you want your story to be clear, in your face, and strong. It’s gotta keep your reader awake!

3) A low character count. The more characters you ask the reader to remember, the more your script becomes an exam as opposed to a script. The reader wants to be entertained, not have their memory tested.

4) A sparse writing style. Again, readers are zipping through your screenplays as fast as they can. Big blocky chunks of text (5-7 lines) slow them down and piss them off. Throw enough of these mega-text blocks in there and a reader will get so pissed he’ll start skipping them entirely.

Let’s take yesterday’s script, “The Revenant,” (about a fur-trader who avenges the men who left him to die) to see how spec-friendly it is. It isn’t the best example because it’s a book adaptation and it was developed in cooperation with a production company. However, The Revenant is a pretty spec-friendly premise and here’s why:

– The plot is easy to follow (clear destination, motivation and goal).

– The character count is low (revolves around 3-4 guys).

– It’s a marketable storyline (revenge plot).

Not convinced? Well, imagine The Revenant next to another script about fur trading. In this other script, we follow the evolution of the fur trade between the years of 1770 and 1910, centering on a Navajo family whose fortunes disintegrate over five generations as the commercialization of the trade eventually puts them out of business, leaving them homeless. Do you see how “un-spec-friendly” that is? The story is long, sprawling, complicated, with lots of characters to remember. It sounds like I’m going to need to take notes. I got news for you. If you ever write a script where the reader has to take notes to remember what’s going on, you haven’t written spec-friendly. You’ve written spec-enemy.

One of the unfortunate side-effects of the spec screenplay system is that, due to factors I mentioned above, it favors genres that fit into an “accelerated reading” state. Therefore, slow period pieces don’t do well on the spec market. Nor do straight dramas. Nor do Westerns. Spec-friendly genres are up-tempo. And this leads us to our fifth rule.

5) Write in one of the six “fast” genres: Comedy, Horror, Thriller, Adventure, Sci-fi, Action.

Not only should your genre be fast, but your story itself should be fast. Any time-frame in excess of one month means your story’s probably too slow-moving for your average reader. Remember, this is a guy whose brain is exhausted from constantly reading junk. He could fall asleep at any moment. So the story most likely to keep him up is the one that’s taking place quickly, the one that’s moving along FAST. Look at some of the recent spec sales. Parents Weekend (about parents who party at their son’s college for one weekend), The Babysitter (about a kid who gets stuck one night with a psycho crazy babysitter), In The Deep (about a girl stuck on a buoy being hunted by a shark). So, rule #6

6) Keep the timeline of your script as short as possible. Under a week is good, but under 72 hours is better.

Finally, in order to write that perfect spec-friendly screenplay, you have to be aware of this simple reality: studios want to make money. The readers are reading for the producers who are producing material for the studios, who are trying to do one thing: Make movies that make as much money as possible. To that end, your spec needs to cover one of the 20 proven subject matters that Hollywood makes money on.

7) Write in one of Hollywood’s 20 proven subject matters. These include:

A. Superheroes

B. Monsters

C. Dinosaurs

D. Pirates

E. Cars

F. Aliens

G. Dystopian Future

H. Apocalyptic Future

I. End of the world/mass destruction

J. Adventure (Indiana Jones, Goonies)

K. Time travel

L. Robots

M. Secret agents

N. Large scale action (Mission Impossible)

O. Large scale sci-fi (Gravity, Star Trek)

P. Fantasy (Lord of the Rings)

Q. Fairy tales

R. Magic

S. Creatures (Vampires, Ghosts, Werewolves, Witches)

T. Sci-fi Fantasy (Guardians, Star Wars)

Look, I know the system is flawed. It isn’t set up to find the best scripts. It’s set up to find easy-to-market high concept screenplays that move quickly and are easy to understand. This is a direct result of the Hollywood Reader system that’s been put in place. But you can either bitch and complain about that and continue to write your epic multi-century fur trading opus that you’re pretty sure is going to be 3% better once you add that knitting accident on page 147, or you can arm your script to excel in this system. You can write the “spec-friendly” screenplay. If I were you, I’d do the latter.